Abstract

The changes of multidimensional fatigue and associated factors in patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer are unknown. This study aimed to evaluate changes in multidimensional fatigue with associated factors during and one month after the brachytherapy. This prospective longitudinal study recruited 188 patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer. They were assessed before the brachytherapy began (T0), after three sessions of brachytherapy (T1), after five sessions of brachytherapy (T2), one month after the whole brachytherapy (T3). Generalized estimating equation analysis was used to determine the factors associated with changes in multidimensional fatigue over time. In this study, total fatigue and five dimensions slightly increased from T0 to T2, with the lowest levels observed at T3. Anxiety, depression, and multidimensional fatigue showed statistically significant differences between T3 and T0, T1, T2. Family adaptability and cohesion showed non-significant changes across four time points. Participants who were older and had more severe anxiety and depression were more likely to experience worse total fatigue (β = 0.084, 0.509, 0.596, respectively), physical fatigue (β = 0.025, 0.078, 0.126, respectively), and reduced motivation (β = 0.027, 0.092, 0.104, respectively). Participants with more severe anxiety and depression were more likely to experience worse general fatigue (β = 0.144 and 0.144, respectively), mental fatigue (β = 0.107 and 0.112, respectively), and reduced activity (β = 0.087 and 0.110, respectively). Older age, more severe anxiety and depression, were significantly associated with worse multidimensional fatigue in patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer. Healthcare professionals need to continuously monitor multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, and depression during and after brachytherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer, ranking as the fourth most prevalent cancer among women globally, now poses a significant health challenge on a global scale1. Almost all instances of cervical cancer are the results of persistent infections caused by high-risk oncogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV)2. Cervical cancer typically does not present noticeable symptoms during early stages, and it is often detected through routine screenings or pelvic exams3. Common symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially after sexual intercourse, as well as a heavy, foul-smelling vaginal discharge4. Patients with different stages would receive different treatments, including surgical interventions, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, concurrent chemoradiotherapy. There are also other approaches including intracavitary brachytherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the use of immunotherapies5. Among these treatment options, brachytherapy stands out as one of the newer approaches. This method involves inserting a radiation source directly into the uterus and vagina, allowing a higher radiation dose to be delivered to the cervix compared to external beam radiotherapy. The advantage of brachytherapy is its ability to target the cervix more precisely while minimizing radiation exposure to surrounding healthy tissues, thus reducing potential toxicity5. Brachytherapy can be administered at a low-dose rate (0.4–2 Gy/h) using caesium-137 via tandem, or at a pulsed-dose rate (using a high-dose rate of iridium-192, with treatments lasting only 10–30 min), or at a high-dose rate (> 12 Gy/h)5. However, the negative effects of brachytherapy are now unclear. The symptoms that participants would suffer during the brachytherapy are necessary to explore.

Previous studies suggested that all treatment modalities would result in long-term adverse effects for cervical cancer patients, particularly impacting their quality of life, including sexual function5. The common physical symptoms they experience include lymphoedema, changes in stool habits, altered bladder function, and sexual difficulties6. The existing study revealed that patients undergoing all types of therapies, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and even palliative treatment, would experience cancer-related fatigue (CRF)7. Fatigue is characterized by a constant and overwhelming feeling of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive exhaustion, which is associated with cancer or its treatments8. Cancer-related fatigue was multidimensional, including general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation9. Fatigue is not directly linked to recent physical activity and frequently interferes with normal daily functioning, making it challenging for patients to carry out routine tasks8. This is particularly challenging because many diagnosed patients are still working and managing family responsibilities. Previous studies showed that 47 years was the median age at diagnosis, and nearly 50% of cases were individuals under 35 years in the USA10and more than 25% of newly diagnoses were aged 40 to 49 years in South Africa11. Therefore, identifying the serious status and associated factors of fatigue for cervical cancer patients is necessary, so that professionals would be able to explore the possible solutions for managing the fatigue for them.

Previous studies have revealed the high prevalence and negative effects of fatigue, but they mostly focused on fatigue occurring after surgery or chemotherapy, and lacked details on changes during these therapies. The fatigue-related symptom cluster was the most serious among other clusters in patients receiving chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer12and fatigue was also the most prevalent symptom among the 40 cancer-related symptoms13. A cross-sectional study indicated that the incidence rate of fatigue in cervical cancer patients after surgery was as high as 99%14. Long-term passive smoking, tumor recurrence, and negative coping style were risk factors of severe fatigue, and patients who earned more than 5000 CNY per month, exercised ≥ 2–3 times a week, experienced higher social support and cohesion were protective factors of severe fatigue14. Patients who had concurrent chemoradiotherapy reported worse fatigue than those who had only surgery15.

At present, the combination of radiotherapy and brachytherapy is still an excellent treatment option for cervical cancer patients16and the brachytherapy has become one of important treatments. Sexual dysfunction is one of the worst side effects of brachytherapy and negatively affects patients’ quality of life17which might further affect the relationship between couples. The impact of family relationship on the fatigue has been indicated in the previous studies. Some studies indicated that marital status, anxiety, and family income had impact on the fatigue in cancer patients18,19. A qualitative study showed that mental fatigue, physical fatigue, the relationship between couples, and sexual experiences would affect among each other20. Additionally, a follow-up study found that the brachytherapy dose was one of the factors linked to chronic fatigue in a significant range of patients following chemoradiotherapy21. A study found that patients receiving definitive chemoradiation for cervical cancer faced a substantial symptom burden and psychosocial toxicity, which led to a reduced quality of life22. Therefore, based on the explored risk factors of fatigue for cervical cancer and other tumors in existing studies, we identified the possible associated factors including some demographic characteristics, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion.

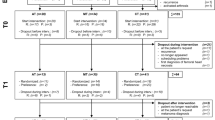

For better identifying the best fatigue intervention point and designing the most practical fatigue management for the patients with cervical cancer undergoing brachytherapy. We conducted a prospective longitudinal study including four time points (T0: before the brachytherapy begins; T1: after three sessions of brachytherapy; T2: after five sessions of brachytherapy; T3: one month after finishing the whole brachytherapy) to explore the changes and its associated factors of total fatigue and its five dimensions during the whole process of brachytherapy and one month follow-up.

Methods

Design

The study adopted a prospective longitudinal design with a convenience sample of patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer.

Participants

The participants included in this study were recruited from March 2024 to October 2024 at the department of radiation oncology of a tertiary hospital in Guangzhou, China. A total of 188 participants were recruited by the professional nurses, all of whom met the following criteria: (1) firstly being diagnosed with cervical cancer by the professional doctors based on histopathological assessment of a cervical biopsy according to the Chinese Gynecological Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline 20245,23; (2) planned to receive the whole brachytherapy in our hospital; (3) over 18 years old; (4) agreed to participate in this study and receive the three times’ follow up investigations; (5) were able to understand the scales and cooperate with the researchers. To eliminate the potential influence of participants’ health conditions and other traumatic life events on fatigue symptoms, the exclusion criteria for participants included (1) being diagnosed with other severe psychiatric difficulties or any other tumors in the same time; and (2) received the brachytherapy or other cancer-related therapies such as surgery, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy before.

Based on a sample size of 5–10 times the number of independent variables and accounting for a 10%-20% dropout rate at each time point, the sample size was determined to be between 66 and 187. Finally, 188 participants completed all four times’ investigations.

All the included patients received brachytherapy with a dose between 30 and 36 Gy per session, and each of them underwent a total of five sessions.

Measurements

The multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion were measured at baseline (before the brachytherapy begins, T0), after three sessions of brachytherapy (T1), after five sessions of brachytherapy (T2), and one month after finishing the whole brachytherapy (T3). Since the time point of the third session was in the middle of the entire brachytherapy treatment, we chose it as the time for T1. The time point of the fifth session, being at the end of the treatment, was chosen as the time for T2. The demographic information was collected at baseline, including socio-demographic information (age, Body Mass Index (BMI), educational level, marital status, per-capita monthly income) and disease-related characteristics (whether received the surgery before, treatment plan).

Multidimensional fatigue was evaluated using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 (MFI-20), developed by Smets et al.9specifically designed to measure fatigue in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. In 2012, Han et al.24 translated the scale into Chinese. The MFI-20 consists of 20 items, each rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely strongly). It includes five subscales: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation. The total score is the sum of the scores from the five subscales, ranging from 20 to 100, with a higher score indicating more severe fatigue. A total score above 60 indicates severe fatigue25. In this study, the MFI-20 had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.887.

Anxiety was assessed using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), a 20-item self-reported tool developed by Zung et al.26 in 1971. It is commonly used for screening anxiety. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (none or a little of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). The original score is calculated by summing the scores of the 20 items, while the standardized score is 1.25 times the original score. Higher scores reflect more severe anxiety. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the SAS was 0.832.

Depression was assessed using the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), a 20-item self-reported measure developed by Zung et al.27 in 1965. It is widely used for screening depression. It includes items related to cognitive, somatic, psychomotor, and affective symptoms. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (none or a little of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). The original score is the total sum of the 20 items, and the standardized score is 1.25 times the original score. Higher scores indicate more severe depression. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the SDS was 0.826.

Family adaptability and cohesion were evaluated using the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale, Second Edition (FACES II). Developed by Olson28 in 1982, the FACES II was later translated into Chinese by Fei et al.29. The scale consists of two dimensions: adaptability and cohesion, with a total of 30 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the FACES II was 0.815.

Data collection

Participants were invited to participate in the study when they came to the radiation oncology outpatient clinic for treatment from March 2024 to October 2024. Before the study begin, the professional nurses in our team would introduce and explain the objectives and procedure to the patients. Those who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate were asked to sign an informed consent form. At T0, all questionnaires were used, and the contact information of patients were collected to facilitate follow-up surveys. The data of T1 (after three sessions of brachytherapy) and T2 (after five sessions of brachytherapy) were collected by professional research nurses after the participants finished the therapy in person. At the follow-up time point (one month after finishing the whole brachytherapy, T3), we collected the data through mobile phone interviews, the professional researchers paraphrased the questionnaire items for the participants and recorded their answers. At T1, T2, and T3, we evaluated all variables except demographic information.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic characteristics, multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion. Trajectories of multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion across four time points were determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA). We used the Bonferroni correction to do the post-hoc test and pair-wise comparison. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) is a regression technique employed to analyze longitudinal data over time, offering both efficiency and unbiased results30. The GEE model employed a linear link function and an unstructured correlation structure, as this combination yielded the lowest Quasi-likelihood under the independence model Criterion (QIC). GEE analysis was employed to identify the variables associated with the trajectories of multidimensional fatigue. The independent variables included age, Body Mass Index (BMI), educational level, marital status, per-capita monthly income, whether received the surgery before, treatment plan, anxiety, depression, family adaptive and cohesion. The significance level for all tests was set at 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Demographic characteristics

Out of the 210 eligible patients approached, 188 completed four assessments, resulting in a response rate of 89.52%. The average age of these included participants was 57.82 years (standard deviation [SD], 11.78), and more than one third of them were above 55 years (36.2%). Because of the specificity of the tumor, all the participants were female. Most of the participants stayed healthy BMI (59.6%), had primary school education or below (38.8%), were married (83.0%), had the per-capita monthly income more than 4000 CNY (43.7%). The majority of the participants were diagnosed as cervical cancer (88.8%), did not receive the surgery before (75.0%), and received the treatment plan combining brachytherapy, external radiation, and chemotherapy (81.4%). The details of the participants’ demographic characteristics are showed in the Table 1.

Temporal changes in multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion

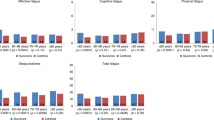

The status of total fatigue at four time points were 57.90 ± 10.89, 58.91 ± 11.23, 59.65 ± 11.79, and 49.12 ± 12.43, approaching the critical threshold of severe fatigue. The total fatigue and four dimensions, including general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation were slightly increased from T0 to T2, and were lowest at T3 (Fig. 1). While the mental fatigue slightly increased from T0 to T1, and decreased from T1 to T3 (Fig. 1). The changes for anxiety and depression were subtle within T0 and T3 (Fig. 2). The values for anxiety, depression, total fatigue and its five dimensions showed statistically significant differences between T3 and T0, T1, T2 (Table 2). Family adaptability and cohesion showed slight changes with non-significant differences across four times (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Significant predictors of total fatigue and its five dimensions

GEE analysis identified the factors associated with total fatigue and its five dimensions. Participants with older age (β = 0.084, 95% CI = 0.005 to 0.112, P = 0.038), more severe anxiety (β = 0.509, 95% CI = 0.370 to 0.647, P < 0.001), and depression (β = 0.596, 95% CI = 0.459 to 0.734, P < 0.001) were more likely to have worse total fatigue. Participants with older age (β = 0.025, 95% CI = 0.003 to 0.048, P = 0.029), more severe anxiety (β = 0.078, 95% CI = 0.039 to 0.117, P < 0.001), and depression (β = 0.126, 95% CI = 0.089 to 0.163, P < 0.001) were also more likely to have worse physical fatigue. In addition, participants with older age (β = 0.027, 95% CI = 0.005 to 0.050, P = 0.015), more severe anxiety (β = 0.092, 95% CI = 0.058 to 0.126, P < 0.001), and depression (β = 0.104, 95% CI = 0.069 to 0.138, P < 0.001) were also more likely to experience worse reduced motivation.

Participants who had more severe anxiety (β = 0.144, 0.107, and 0.087, 95% CI = 0.107–0.180, 0.070–0.143, 0.048–0.126, respectively) and depression (β = 0.144, 0.112, and 0.087, 95% CI = 0.110–0.177, 0.078–0.146, 0.074–0.147, respectively) showed higher possibility to experience worse general fatigue, mental fatigue, and reduced activity. Both family adaptation and cohesion did not show the significant influences on the changes of fatigue and its dimensions. The details of the GEE analysis were showed in Table 3.

Discussion

This study investigated trajectories of multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability and cohesion in patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer. From T0 to T2, multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, and depression increased slightly, and showed lowest at T3. The changes of family adaptability and cohesion during this period did not show significant differences. It was worth to notice that older age, as well as more serious anxiety and depression were associated with worse multidimensional fatigue.

Our study found that patients’ fatigue has existed before the beginning of brachytherapy (T0), which was the same as the findings of Smet et al.31. During the whole brachytherapy treatment, the fatigue of cervical cancer kept increasing slightly, which was the new findings that supplied the blank of this area. We could not absolutely attribute the reasons for fatigue to the brachytherapy, because most of the included participants (94.1%) received not only brachytherapy but also different doses of external radiation and chemotherapy. The serious side effects of fatigue deserve significant attention. A systematic review highlighted that severe fatigue could interfere with daily activities, led to adverse symptoms, diminished quality of life, caused work-related difficulties, relationship problems, and emotional distress, and even affected treatment adherence and clinical outcomes, including recurrence and mortality32. The review by Muthanna et al.33 also indicated that fatigue negatively affected quality of life. Therefore, the findings reminded us the timely and persistent assessment of fatigue was important and necessary.

The key findings of our study were the significant predictive functions of anxiety and depression for the changes of multidimensional fatigue, which gave us the direction to manage the fatigue. Many women who were positively screened for cervical cancer showed heavy psychological burden, with the anxiety and depression as the significant independent predictors34. The serious prevalence and side effects of depression and anxiety in cancer patients received radiotherapy or chemotherapy have been proved in previous studies. A follow-up study with a sample of 1,010 cancer patients revealed that most experienced clinical levels of anxiety (64%), and one-third met clinical levels of depression (31%) within the first five years following their cancer diagnosis35. The evidence from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data showed that depression was positively with gynecologic cancers, including cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer36. The side effects of brachytherapy were not absolutely the same as chemotherapy and external radiation therapy, since brachytherapy caused specific damage to the vagina, especially the sexual difficulties, which might further aggravate patients’ anxiety and depression.

The non-significant findings of family adaptability and cohesion also need our attention. We analyzed that the reasons might include the Chinese cultural characteristics and the limited sensitivity of the scale. Chinese families emphasize on family responsibility, have strong emotional bonds and braveness to meet with the difficulties together. Therefore, this can be the reason why family adaptability and cohesion were not the significant influencing factors on the changes of fatigue. Though the changes of family adaptability and cohesion during this period did not show significantly differences, we could not dismiss the importance of family function during the whole treatment. Family adaptability and cohesion refer to the emotional closeness and connection between family members, which can potentially impact the effectiveness of treatment and rehabilitation to some degree37. The concept of family adaptability and cohesion was first introduced and developed by Olson37 as part of a family function model. This model suggests that family intimacy, adaptability, and communication are key components of family cohesion, and the functioning of the family is closely related to the realization of these internal dynamics38. A qualitative study revealed that women diagnosed with precancerous cervical lesions often experienced depressive symptoms, social isolation, role changes, and a decline in sexuality, and both the women and their partners required information and psychological support39. Additionally, a retrospective study suggested that patients with stress urinary incontinence after cervical cancer surgery exhibited low levels of family resilience40. In a cross-sectional study which investigated 186 patients, quality of life of patients with cervical cancer was affected by the marital status41. Family adaptability and cohesion would affect patients’ quality of life to some content, therefore for better improving the relationship among family members, we need to find some ways to help to alleviate the symptoms of the vagina, provide the psychological instruction, improve the family support, and enhance the happiness in family.

The trajectories of multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, depression, family adaptability, and cohesion throughout the entire treatment, along with the predictors of these changes, provide valuable directions for future research and fatigue management. Firstly, it is important to monitor changes in multidimensional fatigue during the entire brachytherapy treatment to identify the onset and worsening of fatigue. The earlier the intervention, the more effectively it can manage and reduce fatigue. Secondly, the study also emphasizes the importance of managing anxiety and depression symptoms in cervical cancer patients. Based on the findings of this study, we could recommend using existing specific interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy42 and music therapy43to alleviate depression and anxiety. However, existing scientific interventions to alleviate fatigue in cervical cancer patients are limited, with only mindfulness-based stress reduction and network-based positive psychological nursing models being utilized44,45. Therefore, the outcomes would give some evidence for better design of the intervention. Thirdly, the study also indicated the specific of brachytherapy other than chemotherapy or radiotherapy, stressing the need to focus on the relationship between patients and their husbands, and to provide more family support for them.

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, this prospective study was carried out in a single hospital in Guangzhou, China, meaning the findings may not be generalizable to the broader population of cervical cancer patients in other regions or countries. The healthcare access and social support norms are various in different areas of the world, which might also affect the fatigue among these patients. Therefore, to confirm these findings, future research should collect data from multiple hospitals in various cities and involve larger, more diverse participant groups. Secondly, this study did not consider or collect data on all possible factors, focusing mainly on psychological and family factors. Thus, other potential factors should be explored in future research. Thirdly, the lack of information on the stages and concrete brachytherapy protocols of the included participants highlights the need for careful interpretation of the findings. Future studies should recruit cervical cancer patients with more detailed tumor and treatment characteristics. In addition, different data collection methods between T0-T2 (in-person interviews) and T3 (telephone interviews) would cause some unavoidable bias.

Conclusions

In this prospective longitudinal study, the status of multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, and depression slightly increased, while family adaptability and cohesion experienced subtle increases and decreases during brachytherapy, and all symptoms showed significant improvement at the one-month follow-up. Participants with more severe anxiety and depression were more likely to experience worse multidimensional fatigue, and those who were older tended to show worse total fatigue, physical fatigue, and reduced motivation. Healthcare professionals need to continuously monitor multidimensional fatigue, anxiety, and depression during and after brachytherapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of the patients’ privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394 (2018).

Crosbie, E. J., Einstein, M. H., Franceschi, S. & Kitchener, H. C. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 382, 889 (2013).

Stapley, S. & Hamilton, W. Gynaecological symptoms reported by young women: examining the potential for earlier diagnosis of cervical cancer. Fam Pract. 28, 592 (2011).

Lim, A. W. et al. Delays in diagnosis of young females with symptomatic cervical cancer in england: an interview-based study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 64, e602 (2014).

Cohen, P. A., Jhingran, A., Oaknin, A. & Denny, L. Cervical cancer. Lancet 393, 169 (2019).

Pecorelli, S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 105, 103 (2009).

Nowe, E. et al. Cancer-Related fatigue and associated factors in young adult cancer patients. J. Adolesc. Young Adult. 8, 297 (2019).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Vol. 2024 (2024).

Smets, E. M., Garssen, B., Cull, A. & de Haes, J. C. Application of the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20) in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer. 73, 241 (1996).

Waggoner, S. E. Cervical cancer. Lancet 361, 2217 (2003).

Olorunfemi, G. et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of cervical cancer in South Africa (1994–2012). Int. J. Cancer. 143, 2238 (2018).

Tie, H. et al. Symptom clusters and characteristics of cervical cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 9, e22407 (2023).

Zhou, K. N. et al. Symptom burden survey and symptom clusters in patients with cervical cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 31, 338 (2023).

Gu, Z., Yang, C., Zhang, K. & Wu, H. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting sever cancer-related fatigue in patients with cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 24, 492 (2024).

Li, C. C., Chang, T. C., Tsai, Y. F. & Chen, L. Quality of life among survivors of early-stage cervical cancer in taiwan: an exploration of treatment modality differences. Qual. Life Res. 26, 2773 (2017).

Alfrink, J., Aigner, T., Zoche, H., Distel, L. & Grabenbauer, G. G. Radiochemotherapy and interstitial brachytherapy for cervical cancer: clinical results and patient-reported outcome measures. Strahlenther Onkol. 200, 706 (2024).

Cianci, S. et al. Post treatment sexual function and quality of life of patients affected by cervical cancer: A systematic review. Medicina-Lithuania 59 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Identification of distinct fatigue trajectories in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy: an observational longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 33, 298 (2025).

Zdun-Ryzewska, A., Gawlik-Jakubczak, T., Trawicka, A. & Trawicki, P. Fatigue and related variables in bladder cancer treatment - Longitudinal pilot study. Heliyon 10, e35995 (2024).

Al-Naamani, Z. et al. The lived experiences of fatigue among patients receiving haemodialysis in oman: a qualitative exploration. BMC Nephrol. 25, 239 (2024).

Smet, S. et al. Risk factors for late persistent fatigue after chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: an analysis from the EMBRACE-I study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 112, 1177 (2022).

Andring, L. M. et al. Patient reported outcomes for women undergoing definitive chemoradiation for gynecologic cancer: A prospective clinical trial. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 13, e538 (2023).

Wang, D., Xiang, Y. & Zhang, G. Chinese Gynecological Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline 2024 (Scientific and Technical Documentaion, 2024).

Han, Q. & Tian, J. The reliability and validity of the multidimensional fatigue Inventory-20 in cancer patients. Chin. J. Nurs. 06, 548 (2012).

Tian, J. & Hong, J. S. Validation of the Chinese version of multidimensional fatigue Inventory-20 in Chinese patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 20, 2379 (2012).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12, 371 (1971).

Zung, W. W., Richards, C. B. & Short, M. J. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 13, 508 (1965).

Olson, D. Family Inventories: Inventories Used in a National Survey of Families Across the Family Life Cycle (1982).

Fei, L. et al. Preliminary evaluation of Chinese version of FACES II and FES: comparison of normal families and families of schizophrenic patients. Chin. Mental Health J. 5, 198–238 (1991).

Zeger, S. L. & Liang, K. Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42, 121 (1986).

Smet, S. et al. Fatigue, insomnia and hot flashes after definitive radiochemotherapy and image-guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer: an analysis from the EMBRACE study. Radiother Oncol. 127, 440 (2018).

Kang, Y. E. et al. Prevalence of cancer-related fatigue based on severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep-UK. 13, 12815 (2023).

Muthanna, F. et al. Prevalence and impact of fatigue on quality of life (QOL) of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 24, 769 (2023).

Ilic, I. et al. Psychosocial burden of women who are to undergo additional diagnostic procedures due to positive screening for cervical cancer. Cancers 16 (2024).

Sjodin, L., Marklund, S., Lampic, C. & Wettergren, L. Anxiety and depression trajectories in young adults up to 5 years after being diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Med-US. 14, e70715 (2025).

Wang, C., Xu, J., Li, X. & Jiang, L. Depression as a risk factor for gynecological cancers: evidence from NHANES data. Int. J. Womens Health. 17, 615 (2025).

Olson, D. FACES IV and the circumplex model: validation study. J. Marital Fam Ther. 37, 64 (2011).

Wang, N. et al. Effects of family dignity interventions combined with standard palliative care on family adaptability, cohesion, and anticipatory grief in adult advanced cancer survivors and their family caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. Heliyon 10, e28593 (2024).

Celik, N. & Saruhan, A. The experiences of women diagnosed with precancerous cervical lesions, and their spouses, according to the Roy adaptation model: Model-based qualitative research. Appl. Nurs. Res. 81, 151894 (2025).

Wang, J., Lv, N., Yang, L., Zhu, Y. & Sun, L. Family resilience and its influencing factors in patients with stress urinary incontinence after cervical cancer surgery: A retrospective study. Arch. ESP. Urol. 77, 397 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Quality of life and its related-influencing factors in patients with cervical cancer based on the scale QLICP-CE(V2.0). BMC Womens Health. 24, 277 (2024).

Duan, L., Zhang, S., Yan, Q. & Hu, X. Comparative efficacy of different cognitive behavior therapy delivery formats for depression in patients with cancer: A network Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psycho-Oncology 34, e70078 (2025).

Luo, T. et al. Efficacy of music therapy on quality of life in cancer patients: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Psycho-Oncology 34, e70165 (2025).

Gu, Z., Li, B., OuYang, L. & Wu, H. A study on improving cancer-related fatigue and disease-related psychological variables in patients with cervical cancer based on online mindfulness-based stress reduction: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 24, 525 (2024).

Nie, X. Effects of Network-based positive psychological nursing model on negative emotions, cancer-related fatigue, and quality of life in cervical cancer patients with Post-operative chemotherapy. Ann. Ital. Chir. 95, 542 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YYF analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. HX, ZXL, XXJ, WCH, MAD collected the data for this study. QXF was the project leader of this study, and participated in writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All study procedures followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Ethics Certificate Number B2024-544-01). Before the survey, one professional nurse explained the study objectives and procedure. All the included participants signed the informed consents before the survey and they knew that they had the rights to withdraw the study at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Y., Hu, X., Zhang, X. et al. A prospective longitudinal study of the changes in multidimensional fatigue and its associated factors in patients undergoing brachytherapy for cervical cancer. Sci Rep 15, 34831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19219-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19219-9