Abstract

This study examines the role of gender role orientation in shaping body ideals and its impact on disordered eating and muscle dysmorphic symptoms in women. We explore how self-perceived Gender Roles regarding Masculinity and Femininity relate to thinness and muscularity ideals and whether these body ideals mediate the relationship between Gender Roles and disordered eating behaviors. A cross-sectional online survey was conducted with 304 adult women. Participants completed measures assessing gender role orientation, body ideals, disordered eating symptoms, and muscle dysmorphic symptoms. Mediation analyses were performed. Self-reported Masculinity was associated with stronger muscularity ideals, while Femininity predicted a weaker drive for muscularity. The mediation analysis showed that muscularity ideals completely mediated the relationship between self-perceived Masculinity or Femininity and disordered eating symptoms. The study highlights the importance of considering Gender Roles and muscularity ideals when examining the development of body image concerns and disordered eating behaviors. The findings suggest that promoting flexible gender role perceptions could be an effective focus for public health interventions aimed at preventing and reducing disordered eating. Future research should further investigate these relationships in clinical populations and explore additional mediators.

Trial registration: This study was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF, https//osf.io/efn4v May 6, 2024).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

What women consider to be their body ideal, i.e., a desired body shape, size, and composition, is a key determinant of body dissatisfaction, as body ideals establish the standards against which individuals compare their own physical appearance1,2. Body dissatisfaction has been associated with negative affect3, an increased risk for depression4, and most critically, with the development and maintenance of disordered eating5, Body Dysmorphia6, and Eating Disorders (EDs), including Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge-Eating Disorder7,8. Since the treatment of mental health problems associated with body dissatisfaction is posing an increasing challenge to public healthcare systems9, it is important to understand which factors influence women’s current body ideals and how they link to different types of disordered eating.

Body ideals are influenced by the zeitgeist and are becoming increasingly diverse10. In the West, thinness has been idealized since the mid-20th century11, forming the basis of body-related concerns most commonly linked to the perception of being overweight12. Thin-ideal internalization in women has been directly associated with body dissatisfaction1 and has been identified as a predictor of ED onset13, as individuals strive to attain an often unobtainable ideal physique. Furthermore, research suggests that the internalization of a thin ideal frequently continues to be impactful during ED recovery and is a significant predictor of relapse risk14,15.

However, recent years saw a shift, among other trends, towards integrating thinness with athleticism16. Research suggests that, unlike men who often seek a more muscular and voluminous physique, women typically prioritize an athletic build characterized by defined muscles and low body fat17. These new beauty ideals combine a thin physique with increased muscularity, further narrowing beauty standards and creating additional challenges for women striving to meet them18,19. The internalization of the muscularity ideal in both men and women has been associated with dissatisfaction regarding their muscle tone and definition20. Additional evidence indicates that women’s drive for muscularity is strongly linked to harmful behaviors, including disordered eating and exercise dependence21. These behaviors are part of the symptom cluster of Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder22. Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder is a variant of Body Dysmorphia and is characterized by a compulsive preoccupation with muscularity and leanness as well as distorted body image23, which, however, often remains undetected24.

One hypothesized factor in shaping body ideals and thus leading to different forms of disordered eating behaviors among women is gender role orientation25. Gender role orientation refers to self-assessments of how closely one’s personality traits and behaviors align with traditional notions of the concepts of “Femininity” and “Masculinity”26. These masculine and feminine traits shape behavior and are linked to different beliefs and attitudes, including perceptions of one´s ideal body27,28. For instance, in Western cultures, Femininity has been associated with traits such as nurturance and emotional sensitivity, whereas Masculinity has been associated with assertiveness and independence26,29.

There is some indication that Gender Roles can pressure women to conform to specific female body ideals30,31, for instance, findings of an earlier meta-analysis indicated an overall small, heterogeneous positive relationship between Femininity and disordered eating32. Furthermore, women who exhibit characteristics associated with traditional Femininity, such as passivity, emotional dependence, and a strong desire for social approval, show a higher vulnerability to the development of EDs, compared to women scoring lower on Femininity33. In line with these findings, another empirical study suggests that women who identify strongly with traditional feminine roles are more likely to experience disordered eating behavior34. Mahalik et al.35 also found conformity to feminine norms positively related to ED psychopathology. However, Green, Davids, Skaggs, Riopel, & Hallengren36 only found one traditionally feminine characteristic (i.e., thinness orientation) to predict ED symptomatology using the same feminine norms measure as Mahalik et al.35. Furthermore, Behar et al.37 observed that women with less traditionally feminine and more “androgynous” traits were less prevalent among individuals with EDs compared to those without EDs. Yet, some studies question whether traditional Femininity increases the risk of developing EDs. For instance, a negative correlation was identified between Masculinity and scores on ED psychopathology38, while Femininity showed no significant association with unhealthy/disordered eating behavior25.

Research on masculine Gender Roles and disordered eating in women remains scarce. In one mixed gender sample, masculine gender role dimensions (i.e., unmitigated agency, male-typed behaviors and male sex-specific behaviors) were positively associated with the drive for muscularity in women39. Furthermore, undergraduate women with masculine gender traits exhibited higher levels of disordered eating compared to androgynous women40. Lampis et al.41 found that girls exhibiting higher levels of Masculinity were more prone to develop bulimia compared to those with lower Masculinity levels. Contrary to that, Reiter & Davis42 found Masculinity was a protective factor for women regarding disordered body image and eating behavior, and Blazek & Carter43 found that feeling more masculine predicted lower disordered eating behavior in adolescent girls.

The observed heterogeneity in findings regarding the influence of Gender Roles on ED symptoms may be attributable to several factors. For instance, a stronger identification with masculine ideals may also increase the drive for a more muscular physique, potentially leading to excessive strength training or restrictive eating in an effort to alter body composition behaviors often associated with Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder34. While Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder has traditionally been studied in men, its prevalence has increasingly risen among women44,45. To our knowledge, no detailed examination of this context exists to date but may contribute to the heterogeneity in study findings. Furthermore, differences in methodologies and sample characteristics across studies likely contribute to the inconsistencies. For example, measurement inconsistencies or limitations in the assessment of gender role orientations in previous research may have introduced systematic inaccuracies. Many scales have been designed, developed, and widely used for measuring traits traditionally considered as typically male vs. typically female. Most available tools classify individuals solely as either feminine or masculine, without allowing for the identification as both or neither. Early efforts to conceptualize Gender Roles framed Masculinity and Femininity as two poles of one dimension rooted in gender stereotypes allowing individuals to position themselves along this dimension. Another methodological limitation is the exclusive focus on Femininity in certain measures. For example, the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory (CFNI)35 is an 84-item self-report measure with eight subscales and a global score, assessing only women’s adherence to feminine norms within the dominant American culture. The Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI)46, however, measures the internalization of gender-stereotypic traits using 60 adjectives categorized as masculine, feminine, or neutral allowing individuals to score on these independent dimensions. This measure follows a progressive and more valid approach to assessing social gender role orientation. However, this measure, which continues to be widely used, was developed in earlier decades. Over time, shifting Gender Roles have likely reduced the ability to accurately reflect variations in how individuals ascribe stereotypical traits to themselves, today47,48.

Recently, Kachel, Steffens, & Niedlich49 developed the Traditional Masculinity and Femininity Scale (TMF) to address the limitations of earlier conceptualizations of Gender Roles, which framed Masculinity and Femininity as distinct dimensions rooted in gender stereotypes. This measure allows individuals to assess themselves in terms of Femininity and Masculinity independently, enabling identification as both, neither, or somewhere in between. Furthermore, the scale reflects enduring characteristics, including traits, appearances, interests, and behaviors historically associated with women and men, respectively. By extending on this understanding, the TMF scale provides a more nuanced approach by directly measuring Femininity and Masculinity along a two-dimensional spectrum to capture the proposed multidimensionality of Gender Roles.

Also, another reason for the heterogeneity of findings could be that traditional ED measures primarily focus on well-established disorders, potentially overlooking emerging or less commonly recognized conditions such as Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)50 which is often associated with Orthorexia nervosa. Given the relatively limited research on this diagnosis, which is now classified as a feeding and eating disorder affecting individuals across the lifespan51, its distinct symptomatology may not be adequately captured by existing assessment tools.

The present study

Previous studies have established a link between Gender Roles and both disordered eating behaviors and Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms; however, findings have been heterogeneous, and the exact relationships, as well as potential confounding or mediating factors, remain unclear. Building on this previous research and utilizing a new reliable, valid, and bi-dimensional measure for traditional Gender Roles, this study examined the influence of Gender Role orientation on the relationship between body ideals, disordered eating, and Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms.

Since previous measures have primarily assessed Gender Roles as a unidimensional construct, we anticipated that the two-dimensional approach would reveal opposing effect directions for Femininity and Masculinity. Furthermore, based on findings from the literature, we expected Femininity to predict thinness ideals and Masculinity to predict muscularity ideals. We also expected that Gender Roles would not only have a direct effect on ED symptoms and Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms, but that body ideals would serve as a mediator. More specifically, we hypothesized that Femininity would influence ED symptoms through thinness ideals, while Masculinity would impact Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms via muscularity ideals.

To investigate this, we conducted a survey study among women assessing Gender Roles, body ideals, ED symptoms (taking ARFID into account), and Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms, analyzing the data using mediation analysis. To our knowledge, no study to date has employed the TMF scale to explore these relationships. Addressing this gap is crucial, as understanding how gender role orientation influences body ideals and disordered eating can provide valuable insights into the societal and psychological factors shaping disordered eating. Given the evolving nature of Gender Roles and societal norms, exploring these dynamics may provide a foundation for improving therapeutic approaches by better addressing the unique challenges faced by individuals with diverse gender identities and role orientations.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The study examined disordered eating behavior in adult women (ages 18 and older) by analyzing data from a cross-sectional online survey. The project was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EFN4V) and received ethics approval from our faculty´s ethics board (AZ 2022 − 910_1) on March 15, 2024. All study procedures adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all participants before the beginning of the study.

Based on the power estimation from previous studies conducted by our research group52, a total of 300 participants were targeted for recruitment. A two-pronged recruitment strategy was used to guarantee variety within the sample. On May 31, 2024, two-thirds of the participants were recruited via Prolific (https://www.prolific.com/), a widely used online platform for reliable and diverse participant recruitment. The remaining one-third of the sample data was collected through personal contacts, university mailing lists, and advertisements on the university website between May 8 and June 27, 2024. The survey was administered using jsPsych53. Participants were informed that the study focused on disordered eating among women. Those recruited via Prolific received compensation of £4.50, while university students in the convenience sample earned research participation credits.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables

Participants provided demographics, including gender (man, woman, diverse/intersex, or no answer), age, weight, height, and sexual orientation (coded non-heterosexual vs. heterosexual). Although only female individuals were eligible to participate via Prolific, we included multiple gender identity options to allow participants to self-identify in line with an inclusive understanding of gender. Following the German Federal Statistical Office´s updated definition54, participants were asked to indicate if they had a migration background (yes/no), based on the question “Were you or at least one of your parents born abroad?”. Moreover, marital status (single, married, divorced, or widowed), living situation (alone or with others), and education level (≤ 12 years or > 12 years) were recorded. Participants were asked open-ended questions about a potential history of EDs and if they were currently undergoing treatment. Additionally, participants were questioned whether they had previously participated in this study (yes/no). An attention check was included in the survey to ensure data integrity55.

Gender roles

The Traditional Masculinity-Femininity Scale (TMF)49 was used to assess participants´ identification with feminine and masculine Gender Roles. The scale evaluated self-perceived Masculinity and Femininity by evaluating traits, interests, appearances, and behaviors traditionally associated with each gender. Masculinity and Femininity are each measured as individual dimensions in the TMF. Participants´ responses were scored on a four-item Likert scale that addresses the two core aspects of gender role-associated self-concept: gender role adaptation (how individuals currently perceive their gender role, e.g., “I consider myself as.”) and gender role preference (their interests, beliefs, and outward appearance concerning traditional Masculinity and Femininity, e.g., “Traditionally, my outer appearance would be considered.”). The response options ranging from 1 = not at all masculine/feminine to 4 = completely masculine/feminine.

Both scales demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = 0.83 for the Masculinity scale and Cronbach’s α = 0.84 for the Femininity scale. The Gender Trait Difference was calculated as the difference between self-reported Masculinity and Femininity scores, with higher values indicating greater Masculinity relative to Femininity.

Body ideals

To assess two dimensions of body image ideals in women, we used the Female Body Scale (FBS) and the Female Fit Body Scale (FFITBS)56. The FBS presents nine female body images ranging from emaciated to obese, whereas the FFTIBS shows nine images spanning from emaciated to highly muscular. For each series, participants were asked to select the image that most accurately reflected their current and ideal body shape. In the FFTIBS scale, ratings ranged from 0 (representing the most emaciated body) to 8 (indicating the most muscular), and in the FBS scale, from 0 (most obese) to 8 (most emaciated), with higher values reflecting a stronger Muscularity Ideal and Thinness Ideal, respectively.

Disordered eating symptoms

We utilized the German version of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q)57, which assesses behavioral and cognitive symptoms of disordered eating throughout the preceding 28 days. The questionnaire includes 22 attitudinal items (e.g., “Have you had a definite fear that you might gain weight”) along with six additional items assessing episodes of overeating, binge eating, binge days, and purging behavior (e.g., “How often during the past 28 days have you eaten an amount of food that others would regard as unusually large under similar circumstances?”), all rated on a seven-point scale from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). Since the factor structure of the EDE-Q has been questioned by previous research58,59, this study only used the global score, which demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

To evaluate ARFID symptoms, we adapted the Eating Disorders in Youth Questionnaire (EDY-Q)60. Originally developed for use in children and adolescents, the EDY-Q has recently been adapted for adults to allow broader applicability across age groups61. This questionnaire includes fourteen items addressing functional dysphagia (FD; e.g., “I am afraid of swallowing food”), selective eating (SE; e.g., “I am a picky eater”), food avoidance (FA; e.g., “If I was allowed, I would not eat”), and concerns related to low body weight. Additional questions on ARFID exclusion criteria such as pica, rumination, and weight/shape concerns were not included in the scale calculations. Participants´ responses were rated on a seven-point scale from 0 (never) to 6 (always). We report the total mean score of the EDY-Q, which showed a Cronbach’s α of 0.60. This moderate internal consistency can be explained by the FA subscale, which demonstrated low internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.35), thereby contributing to the overall reliability of the total score. In addition, both the FD subscale (Cronbach’s α = 0.74) and the SE subscale (Cronbach’s α = 0.71) showed acceptable internal consistency within the sample.

Orthorexic eating behavior, characterized by an unhealthy obsession with healthy eating that may result in psychological, physical, and social impairments, was assessed using the ten item Duesseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS)62. Participants rated their responses to statements such as “It is more important to me to eat healthy food than to enjoy it” on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (“does not apply to me”) to 4 (“applies to me”). We report the total sum score. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency in our sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), which was comparable to the reliability reported by the original authors (α = 0.84).

Muscle dysmorphic disorder

Moreover, we included the validated German version of the Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (MDDI)63, which utilizes thirteen questions (e.g., “I think my legs are too thin”) scored on a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (often) to evaluate muscularity-related body image concerns and behaviors. The questionnaire includes the three subscales drive for size (DS), appearance intolerance (AI), and functional impairment (FI), which all demonstrated high internal consistency (DS: Cronbach’s α = 0.80; AI: Cronbach’s α = 0.84; FI: Cronbach’s α = 0.84). We report the subscales as well as the total mean score, which had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 30.0.0.0 (172)64 with the PROCESS macro version 4.265 for mediation analyses. The figure was created using Python version 3.7.966, utilizing the matplotlib package67 and networkx68.The reliability of the measures used in this study was evaluated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (α). Cronbach’s α values above 0.70 were considered acceptable, with values over 0.80 indicating strong internal consistency69. Descriptive results are reported as means, SDs, or frequencies and percentages. Non-parametric Kendall’s Tau correlation coefficients were computed to examine the associations between the different assessment measures. The significance level for all inferential analyses was set at p ≤.05. Mediation analyses were performed to investigate the mediating roles of Muscularity and thinness ideals in the relationship between self-reported Masculinity and all outcomes, namely EDE-Q, EDY, and MDDI. A parallel mediation framework was utilized, allowing the simultaneous assessment of the mediating effects of Muscularity and thinness ideals in the relationship between self-reported Masculinity (and Femininity, respectively) and the EDE-Q global score, while controlling for age and sexual orientation by including them as a covariates in the model. This approach accounted for the unique contribution of each mediator while controlling for the influence of the other. For the mediation analysis, we utilized PROCESS v4.2 model four, employing a bootstrapped approach with 5,000 samples and a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance of the direct and indirect effects was assessed at the α = 0.05 level, including coefficients and p-values, were examined to interpret the magnitude and significance of these effects.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 304 individuals were initially recruited for the study. We excluded five multivariate outliers and eight participants who either did not disclose their gender or identified as non-binary. Consequently, the final sample comprised n = 291 participants included in the analysis. The mean age of the sample was 28.49 years (SD = 9.54, range 18–64) and the average body mass index (BMI) was 23.42 (SD = 5.10). In terms of sexual orientation, 66.3% (n = 193) reported exclusive attraction to the opposite gender, 22.3% (n = 65) reported attraction to men and women, and 7.6% (n = 22) reported exclusive attraction to the same gender, resulting in 29.9% (n = 87) indicating a non-heterosexual orientation. Furthermore, 29.9% (n = 87) of participants self-identified as having a migration background. Regarding educational attainment, 83.9% (n = 244) reported completing more than 12 years of schooling. With regard to relationship status, 77.7% (n = 226) indicated being single, 19.9% (n = 58) were married or in a committed partnership, and 2.4% (n = 7) reported being divorced. 72.9% (n = 212) of participants resided in shared households, whereas 26.8% (n = 78) reported living alone.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

The analysis revealed several noteworthy associations between gender traits and the psychological measures under study. Femininity and Masculinity were negatively correlated, indicating a tendency for these traits to be perceived or reported in contrast to one another within the sample. However, the strength of the correlation does not indicate perfect opposition, suggesting that Femininity and Masculinity coexist to varying degrees within individuals’ self-concept. Self-ascribed Femininity showed small negative correlations with the EDY mean total score and the MDDI mean total score. In contrast, Masculinity demonstrated weak positive associations with the EDY mean total score, the MDDI mean total score, and all three MDDI subscales: DS, AI, and FI.

The EDE-Q Global score was strongly positively correlated with the DOS total sum score, the MDDI mean total score, and the MDDI subscale AI. Additionally, the DOS total sum score was positively associated with the MDDI mean total score and its FI subscale.

Notably, neither Femininity nor Masculinity showed significant correlations with the EDE-Q Global score, the Thinness Ideal, or the Muscularity Ideal. The correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for the key measures and variables can be found in Table 1.

Mediation Analyses – Direct effects

Femininity

Regarding perceived Femininity and ED symptoms measured by the EDE-Q, we found no direct effect of Femininity (Table 2). However, avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors as measured by the EDY was predicted significantly by Femininity, in terms of higher feminine self-descriptions being associated with lower EDY scores. Femininity had no significant direct effect on the DOS sum score. Notably, Femininity had no direct effect on the Thinness ideal, which was contrary to expectations. One possible explanation for this finding is the low variance in thinness ideals scores within the sample, which was only 0.73. Responses on the 0 to 8 scale ranged exclusively between 5.00 and 8.00. Hence, low predictor variability may have reduced power and masked significant effects. However, perceived Femininity had a significant direct effect on muscularity ideals, with a stronger feminine self-description predicting a significantly lower drive for a muscular body ideal. Detailed statistics for the direct effects of Femininity on the mediator and outcome variables are presented in Table 2.

Masculinity

Masculinity did not significantly predict EDE-Q global scores, indicating no direct association with overall ED symptoms (Table 2). However, it was a significant predictor of EDY scores, suggesting that higher self-perceived Masculinity was directly linked to increased avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors in our sample. No significant direct effect was observed for the DOS total score. In contrast, Masculinity showed a significant positive association with the MDDI mean score, indicating a direct link to higher levels of muscularity-oriented body image disturbance. Additionally, individuals with a stronger masculine self-description were more likely to endorse a muscular body ideal, while no significant association was found with thinness ideals. Table 2 summarizes these direct relationships between Masculinity and both the mediator and outcome variables.

Gender trait difference

Further analyses revealed that a higher Gender Trait Difference—reflecting stronger self-identification as masculine relative to feminine—was significantly associated with increased avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors, as indicated by higher EDY-Q total mean scores. Additionally, individuals with a greater Gender Trait Difference reported significantly higher levels of Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms, as measured by the MDDI total score, suggesting that a more masculine self-perception was linked to elevated muscularity-related body image concerns. A significant positive direct effect was also found between Gender Trait Difference and the endorsement of a muscularity ideal, indicating that participants who perceived themselves as more masculine than feminine were more likely to express a stronger preference for a muscular body ideal. A summary of how Gender Trait Difference directly influences the mediator and outcome variables is presented in Table 2.

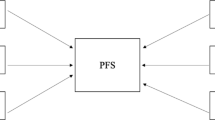

Mediation

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized relationships between the study variables using a path diagram. In this diagram, each node represents a variable, and the arrows indicate the proposed directions of influence between them. The thickness of the arrows corresponds to the magnitude of the effects. Color coding was applied to aid interpretation, with blue arrows indicating significant positive effects, orange indicating significant negative effects, and gray indicating non-significant effects.

As shown in the diagram and reported above, neither masculine nor feminine self-descriptions had a significant direct effect on global EDE-Q scores (ps > 0.24). However, the mediation analysis revealed meaningful indirect effects. Specifically, there was a significant positive association between self-perceived Masculinity and endorsement of muscularity ideals, while Femininity was significantly negatively associated with muscularity ideals. In turn, muscularity ideals had a significant negative effect on EDE-Q global scores.

These findings suggest that the impact of Masculinity and Femininity on ED symptoms is fully mediated through muscularity ideals - in other words, their effect on disordered eating symptoms occurs solely through their connection to internalized muscularity ideals.

Path diagram of mediation analysis of the effect of Masculinity and Femininity on Eating Disorder Pathology mediated by Muscularity and Thinness Ideals. Analysis controlled for age and sexual orientation. *effect is significant at the 0.05 level; **effect is significant at the 0.01 level.; TMF = Traditional Masculinity-Femininity Scale49, EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire57, EDY-Q = Eating Disorders in Youth-Questionnaire60, DOS = Duesseldorf Orthorexia Scale62, MDDI = Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (Zeeck et al., 2018), blue path = positive effect, orange path = negative effect, gray path = non-significant effect.

The bootstrapped analysis provided evidence that Masculinity and Femininity influenced EDE-Q global scores indirectly through muscularity ideals (see Table 3). Once this indirect pathway was taken into account, no significant direct effects of either Masculinity or Femininity on disordered eating symptoms persisted.

The mediation analyses conducted for Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms (i.e., MDDI total score) and avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors (i.e., EDY total score) did not reveal any significant indirect effects via muscularity ideals or thinness ideals.

Discussion

Gender Roles (i.e., social norms and stereotypes associated with Masculinity and Femininity) are enacted and adopted throughout life and have been shown to influence the risk of EDs70. Using the TMF, a newly validated and bi-dimensional measure of traditional Gender Roles, we found that Masculinity predicted stronger muscularity ideals, while Femininity predicted weaker drive for muscularity in a sample of women. Additionally, higher self-reported Masculinity was linked to increased avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors, and participants with higher Masculinity relative to Femininity scores were more likely to exhibit such eating patterns. However, neither masculine nor feminine self-description significantly influenced thinness ideals or EDE-Q global scores. Furthermore, our mediation analysis revealed a mediation effect, indicating that the influence of self-described Masculinity and Femininity on ED symptoms was explained through their effects on muscularity ideals.

Our results indicate that, as anticipated, the two-dimensional approach to measuring Gender Roles revealed opposing effect directions for Femininity and Masculinity on avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors and Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms. Specifically, perceived Femininity had a reducing effect, while Masculinity had an amplifying effect. This may help explain previously inconsistent findings in the literature, as earlier studies often lacked a bidimensional and up-to-date assessment of Gender Roles34,36,41,43.

Self-ascribed Masculinity in this sample of women positively predicted muscularity ideals, as anticipated. Contrary to expectations, however, Femininity did not predict thinness ideals. This may be due to the restricted range of thinness ideal scores, which could have limited variability and reduced the power to detect significant effects. In other words, the women in this sample showed a highly uniform idealization of thinness. Femininity, however, was negatively associated with muscularity ideals. Furthermore, we found that Gender Roles were associated with EDE-Q scores indirectly through muscularity ideals, with higher Masculinity linked to greater endorsement of muscularity ideals, which in turn appeared to relate to lower disordered eating symptoms—suggesting a potentially protective role.

These findings indicate that muscularity ideals may play a meaningful role in the development of ED pathology. However, the negative association between muscularity ideals and EDE-Q scores, suggesting a potential protective effect, contradicts findings from other studies, which have reported positive (or null) associations between appearance ideals and disordered eating8. A possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy may lie in the design of the EDE-Q itself, which primarily assesses thinness-oriented eating pathology59. Individuals with higher muscularity ideals may shift their focus away from thinness toward muscularity-driven body goals. Such a shift may involve disordered behaviors, e.g., one-sided nutrition plans that are not calorically restricted and involve the consumption of (excessive) proteins and the avoidance of fats during “bulk” phases, accompanied by weight-lifting regimens, or the use of performance-enhancing substances71, all of which the EDE-Q does not effectively capture. As a result, lower EDE-Q scores in this group may reflect limitations of the assessment method rather than a true protective role of muscularity ideals.

Achieving a muscular physique is an increasingly prevalent concern among women72. The present study highlights that aspects of muscularity ideals may be important in the etiology of EDs. However, the EDE-Q - despite being considered the gold standard in ED assessment - does not include any items addressing muscularity-related concerns. There is a need for data-driven, validated diagnostic tools that capture the full spectrum of ED-relevant features in order to improve diagnostic accuracy and ensure timely access to appropriate support services.

Research indicates that disordered eating behaviors are prevalent in the general population and represent significant public health concerns. Between 2000 and 2018, the worldwide prevalence of EDs more than doubled, rising from 3.4 to 7.8%73. This increase is particularly alarming given that EDs have one of the highest mortality rates among psychiatric disorders74. Therefore, preventing EDs should be a priority within public health policies and initiatives. Considering diverse understandings of Gender Roles and variations in the internalization of gender ideals – particularly among women – may be valuable in a clinical context to support more individualized treatment approaches. On a broader scale, promoting flexible gender norms may support public health efforts to reduce socio-cultural risk factors associated with body dissatisfaction and disordered eating.

Furthermore, our findings suggest that fitness and muscularity ideals may be increasingly embedded in German society as muscularity ideals were prominent in our sample. This aligns with75, who highlight the growing prominence of muscularity in contemporary beauty standards. However, since our sample was not representative, these results cannot be generalized to the broader population with certainty.

In an earlier study, women with no discrepancy between their experienced and ideal gender perception reported fewer anorexic and bulimic symptoms, less concern with body shape, and higher self-esteem than those with a discrepancy76. However, further research is needed to explore discrepancies in gender identification in relation to a bi-dimensional measure of Gender Roles.

Previous research suggests that sexual orientation may influence body image and eating behaviors, likely mediated by distinct sociocultural pressures, minority stress, and divergent gender role expectations77. The minority stress theory78,79 posits that sexual and gender minorities who either experience or fear stigma and discrimination or have internalized homophobia are at increased risk for adverse mental health outcomes, including disordered eating80. A recent study reports elevated rates of eating pathology among sexual and gender minority youths and adults, which have indeed been linked to experiences of stigma and discrimination81. In the present study, sexual orientation was included as a control variable, and the observed mediation effects were not attributable to variance in sexual orientation. Nevertheless, sexual orientation may intersect with gender role internalization in ways that shape body image- and eating-related outcomes. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples should investigate how such intersections influence the internalization of gender roles, as this may be a pathway through which body image concerns and disordered eating develop in sexual and gender minorities.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, certain limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. It cannot be ruled out that additional factors influence the relationship between Gender Roles and ED pathology. Furthermore, we did not find any mediating effect of muscularity or thinness ideals on Muscle Dysmorphic Symptoms or avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors. This suggests that the proposed mediation model does not sufficiently explain the variance in these outcomes. Further studies should explore alternative mediators, including body dissatisfaction, perfectionism, and social comparison tendencies, and examine moderation effects to better understand the complex interplay between Gender Roles, body ideals, and disordered eating behaviors.

While this study found no significant association between Femininity and the Thinness Ideal, this finding should be interpreted with caution. The high endorsement of thinness in our sample may have resulted in a range restriction, limiting the statistical power to detect potential associations. Moreover, the FBS captures body ideals as a unidimensional construct, which may not reflect more nuanced aspects of thinness and muscularity ideals, such as the degree of internalization or variations in motivational or cultural aspects. Future studies should employ more nuanced and multidimensional measures of appearance ideals to better capture the complexity of these constructs and their associations.

Another limitation concerns the low reliability of the EDY-Q, particularly due to the low internal consistency observed in the FA subscale. While this may reduce the precision and interpretability of the findings, it may also mirror the fact that the underlying construct has not yet been fully established, highlighting the need for further conceptual clarification and empirical investigation.

In this study, we focused on women to establish clear initial effects. However, the generalizability to other groups, such as men, remains uncertain.

We used Prolific, which, despite its good metrics regarding data quality and participant diversity, still offers limited control over the quality of the data -similar to most online studies82.

This study examined body ideals as one important aspect of body dissatisfaction, which is widely understood to be a multifaceted construct2. While participants reported their body ideals, how they interpret or evaluate these ideals remains unclear. Additionally, the emotional and behavioral responses that may arise from perceived discrepancies between actual and ideal body are not yet well understood. Future research should explore these broader dimensions to gain a more nuanced understanding of body dissatisfaction and its relevance to ED pathology.

Conclusion

This study confirms that Gender Roles influence body ideals and disordered eating behaviors. Masculinity was linked to stronger muscularity ideals and higher avoidant-restrictive eating behaviors, while Femininity predicted a weaker muscularity idealization. Mediation analysis showed that muscularity ideals fully explained the link between Gender Roles and ED symptoms. Promoting flexible gender role perceptions could be an effective focus for public health interventions aimed at preventing and reducing disordered eating. Future research should further examine muscularity ideals, particularly in representative samples as well as clinical populations, and explore alternative mediators to refine treatment strategies. Additionally, Gender Roles and muscularity ideals should be considered as important facets in the understanding and assessment of eating disorders.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARFID:

-

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- BSRI:

-

Bem Sex Role Inventory

- CFNI:

-

Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DOS:

-

Duesseldorf Orthorexia Scale

- DS:

-

Drive for Size (subscale of MDDI)

- EDE:

-

Q–Eating Disorder Examination–Questionnaire

- EDs:

-

Eating Disorders

- EDY:

-

Q–Eating Disorders in Youth–Questionnaire

- FA:

-

Food Avoidance (subscale of EDY–Q)

- FD:

-

Functional Dysphagia (subscale of EDY–Q)

- FBS:

-

Female Body Scale

- FFITBS:

-

Female Fit Body Scale

- FI:

-

Functional Impairment (subscale of MDDI)

- JS:

-

JavaScript

- MDDI:

-

Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory

- MDD:

-

Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder

- OSF:

-

Open Science Framework

- SE:

-

Selective Eating (subscale of EDY–Q)

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- TMF:

-

Traditional Masculinity–Femininity Scale

References

Paterna, A., Alcaraz-Ibáñez, M., Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M. & Sicilia, Á. Internalization of body shape ideals and body dissatisfaction: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54, 1575–1600. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23568 (2021).

Cash, T. F. Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image. 1, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1 (2004).

Sala, M., Linde, J. A., Crosby, R. D. & Pacanowski, C. R. State body dissatisfaction predicts momentary positive and negative affect but not weight control behaviors: an ecological momentary assessment study. Eat. Weight Disord - Stud. Anorexia Bulim Obes. 26, 1957–1962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01048-6 (2021).

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Slater, A. & Bray, I. Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: a prospective study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 75, 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213033 (2021).

Larson, N., Loth, K. A., Eisenberg, M. E., Hazzard, V. M. & Neumark-Sztainer, D. Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating are prevalent problems among U.S. Young people from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds: findings from the EAT 2010–2018 study. Eat. Behav. 42, 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101535 (2021).

Ryding, F. C. & Kuss, D. J. The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychol. Pop Media. 9, 412–435. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000264 (2020).

Stice, E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 128, 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825 (2002).

Mallaram, G. K., Sharma, P., Kattula, D., Singh, S. & Pavuluru, P. Body image perception, eating disorder behavior, self-esteem and quality of life: a cross-sectional study among female medical students. J. Eat. Disord. 11, 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00945-2 (2023).

Ahmed, M. et al. Global and regional economic burden of eating disorders: A systematic review and critique of methods. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 58, 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24302 (2025).

Aniulis, E., Nicholls, M. E. R., Thomas, N. A. & Sharp, G. The role of social context in own body size estimations: an investigation of the body schema. Body Image. 40, 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.01.017 (2022).

Swami, V. Cultural influences on body size ideals. Eur. Psychol. 20, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000150 (2015).

Brunner, R. & Resch, F. Dieting behavior and body image. In Societal Change. Handb. Eat. Disord. Obes 9–14 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-67662-2_2.

Stice, E., Gau, J. M., Rohde, P. & Shaw, H. Risk factors that predict future onset of each DSM–5 eating disorder: predictive specificity in high-risk adolescent females. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000219 (2017).

Bardone-Cone, A. M. et al. Defining recovery from an eating disorder: conceptualization, validation, and examination of psychosocial functioning and psychiatric comorbidity. Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.001 (2010).

Heinberg, L. J. et al. Validation and predictive utility of the Sociocultural attitudes toward appearance questionnaire for eating disorders (SATAQ-ED): internalization of Sociocultural ideals predicts weight gain. Body Image. 5, 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.02.001 (2008).

Benton, C. & Karazsia, B. T. The effect of thin and muscular images on women’s body satisfaction. Body Image. 13, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.11.001 (2015).

McCreary, D. R. & Sasse, D. K. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 48, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596271 (2000).

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S. & Heinberg, L. J. The Sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ‐3): development and validation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 35, 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10257 (2004).

Homan, K., McHugh, E., Wells, D., Watson, C. & King, C. The effect of viewing ultra-fit images on college women’s body dissatisfaction. Body Image. 9, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.07.006 (2012).

Hoffmann, S. & Warschburger, P. Prospective relations among internalization of beauty ideals, body image concerns, and body change behaviors: considering thinness and muscularity. Body Image. 28, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.011 (2019).

Campos, P. F. et al. Drive for muscularity Em mulheres: Uma Revisão Sistemática. Motricidade 15, 134–144 (2019).

Cooper, M. et al. Muscle dysmorphia: A systematic and meta‐analytic review of the literature to assess diagnostic validity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 1583–1604. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23349 (2020).

Pope, H. G., Gruber, A. J., Choi, P., Olivardia, R. & Phillips, K. A. Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 38, 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71400-2 (1997).

Cunningham, M. L. et al. Muscle dysmorphia: an overview of clinical features and treatment options. J. Cogn. Psychother. 31, 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.31.4.255 (2017).

Hepp, U., Spindler, A. & Milos, G. Eating disorder symptomatology and gender role orientation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 37, 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20087 (2005).

Bem, S. L. On the utility of alternative procedures for assessing psychological androgyny. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 45, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.45.2.196 (1977).

Mahalik, J. R., Locke, B. D., Theodore, H., Cournoyer, R. J. & Lloyd, B. F. A cross-national and cross-sectional comparison of men’s gender role conflict and its relationship to social intimacy and self-esteem. Sex. Roles. 45, 1–14 (2001).

Barber, N. Gender differences in effects of mood on body image. Sex. Roles. 44, 99–108 (2001).

Harris, E. A. & Griffiths, S. The differential effects of state and trait masculinity and femininity on body satisfaction among sexual minority men. Body Image. 45, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.01.007 (2023).

Finne, E., Schlattmann, M. & Kolip, P. Gender role orientation and body satisfaction during adolescence–Cross-sectional results of the 2017/18 HBSC study. J. Heal Monit. 5, 37 (2020).

Grogan, S. Promoting positive body image in males and females: contemporary issues and future directions. Sex. Roles. 63, 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9894-z (2010).

MurnenSK & SmolakL Femininity, masculinity, and disordered eating: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 22, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199711)22:3<231::AID-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-O (1997).

Lakkis, J., Ricciardelli, L. A. & Williams, R. J. Role of sexual orientation and gender-related traits in disordered eating. Sex. Roles. 41, 1–16 (1999).

Murray, S. B., Rieger, E., Karlov, L. & Touyz, S. W. Masculinity and femininity in the divergence of male body image concerns. J. Eat. Disord. 1, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-11 (2013).

Mahalik, J. R. et al. Development of the conformity to feminine norms inventory. Sex. Roles. 52, 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3709-7 (2005).

Green, M. A., Davids, C. M., Skaggs, A. K., Riopel, C. M. & Hallengren, J. J. Femininity and eating disorders. Eat. Disord. 16, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260802115829 (2008).

Behar, R. A., de la Barrera, C. M. & Michelotti, C. J. Identidad de Género y Trastornos de La conducta alimentaria. Rev. Med. Chil. 129. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872001000900005 (2001).

Garner, D. M. Eating Disorder inventory-2: Professional Kit (Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991).

McCreary, D. R., Saucier, D. M. & Courtenay, W. H. The drive for muscularity and masculinity: testing the associations among Gender-Role traits, behaviors, attitudes, and conflict. Psychol. Men Masc. 6, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.6.2.83 (2005).

Pritchard, M. Disordered eating in undergraduates: does gender role orientation influence men and women the same way?? Sex. Roles. 59, 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9449-8 (2008).

Lampis, J., Cataudella, S., Busonera, A., De Simone, S. & Tommasi, M. The moderating effect of gender role on the relationships between gender and attitudes about body and eating in a sample of Italian adolescents. Eat weight Disord - Stud anorexia. Bulim Obes. 24, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0372-2 (2019).

Reiter, M. E., Davis, S. N. & GENDERED PERSONALITIES AND DEVELOPMENT OF EATING DISORDERS Coll. STUDENTS ;40:27–39. (2014).

Blazek, J. L. & Carter, R. Understanding disordered eating in black adolescents: effects of gender identity, Racial identity, and perceived puberty. Psychol. Men Masculinities. 20, 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000207 (2019).

Cerea, S. et al. Validation of the muscle dysmorphic disorder inventory (MDDI) among Italian women practicing bodybuilding and powerlifting and in women practicing physical exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 9487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159487 (2022).

Steinfeldt, J. A., Carter, H., Benton, E. & Steinfeldt, M. C. Muscularity beliefs of female college Student-Athletes. Sex. Roles. 64, 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9935-2 (2011).

Bem, S. L. The measurement of psychological androgyny. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 42, 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215 (1974).

Sczesny, S., Bosak, J., Neff, D. & Schyns, B. Gender stereotypes and the attribution of leadership traits: A Cross-Cultural comparison. Sex. Roles. 51, 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-0715-0 (2004).

Ebert, I. D., Steffens, M. C. & Kroth, A. Warm, but maybe not so Competent?—Contemporary implicit stereotypes of women and men in Germany. Sex. Roles. 70, 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0369-5 (2014).

Kachel, S., Steffens, M. C. & Niedlich, C. Traditional Masculinity-Femininity scale. PsycTESTS Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/t56492-000 (2017).

Zimmerman, J. & Fisher, M. Avoidant/Restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. 47, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.02.005 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Eschrich, R. L., Halbeisen, G., Steins-Loeber, S., Timmesfeld, N. & Paslakis, G. Investigating the structure of disordered eating symptoms in adult men: A network analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord Rev. 33, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3131 (2025).

de Leeuw, J. R., Gilbert, R. A. & Luchterhandt, B. JsPsych: enabling an Open-Source collaborative ecosystem of behavioral experiments. J. Open. Source Softw. 8, 5351. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05351 (2023).

Statistisches Bundesamt. ;2010:1–519.Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2017 (2018).

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T. & Davidenko, N. Instructional manipulation checks: detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45, 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009 (2009).

Ralph-Nearman, C. & Filik, R. Development and validation of new figural scales for female body dissatisfaction assessment on two dimensions: thin-ideal and muscularity-ideal. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09094-6 (2020).

Hilbert, A., Tuschen-Caffier, B., Karwautz, A., Niederhofer, H. & Munsch, S. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: Evaluation der deutschsprachigen Übersetzung [Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: psychometric properties of the German version]. Diagnostica 2007. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924.53.3.144

Laskowski, N. M., Halbeisen, G., Braks, K., Huber, T. J. & Paslakis, G. Factor structure of the eating disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in adult men with eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00757-4 (2023).

Laskowski, N. M., Halbeisen, G., Braks, K., Huber, T. J. & Paslakis, G. Exploratory graph analysis (EGA) of the dimensional structure of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire (EDE-Q) in women with eating disorders. J. Psychiatr Res. 163, 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.05.063 (2023).

Hilbert, A. & van Dyck, Z. Eating Disorders in Youth-Questionnaire. German version. Univ Leipzig Http//Nbn (2016). Http//Nbn-Resolving.de/Urnnbndebsz15qucosa-197236

Hilbert, A., Zenger, M., Eichler, J. & Brähler, E. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorders in Youth-Questionnaire when used in adults: prevalence estimates for symptoms of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and population norms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54, 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23424 (2021).

Barthels, F., Meyer, F. & Pietrowsky, R. Die Düsseldorfer orthorexie Skala–Konstruktion und evaluation eines Fragebogens Zur erfassung ortho-rektischen ernährungsverhaltens. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 44, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000310 (2015).

Zeeck, A. et al. Muscle dysmorphic disorder inventory (MDDI): validation of a German version with a focus on gender. PLoS One. 13, e0207535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207535 (2018).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 30.0 2023.

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A regression-based Approach (Guilford, 2017).

Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, version 3.7.9 2020. https://www.python.org

Hunter, J. D. & Matplotlib A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2007.55 (2007).

Hagberg, A., Swart, P. J. & Schult, D. A. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using networkx. Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/960616 (2008).

Taber, K. S. The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 48, 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 (2018).

Breton, É., Juster, R. & Booij, L. Gender and sex in eating disorders: A narrative review of the current state of knowledge, research gaps, and recommendations. Brain Behav. 13. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2871 (2023).

Laskowski, N. M., Zaiser, C., Müller, R., Brandt, G. & Paslakis, G. Mapping the pathway to anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) use. Compr. Psychiatry. 141, 152602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2025.152602 (2025).

Jürgensen, V., Halbeisen, G., Lehe, M. S. & Paslakis, G. Muscularity concerns and disordered eating symptoms in adult women: A network analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3192 (2025).

Pastore, M. et al. Alarming increase of eating disorders in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 263, 113733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113733 (2023).

Castellini, G. et al. Mortality and care of eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 147, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13487 (2023).

Bozsik, F., Whisenhunt, B. L., Hudson, D. L., Bennett, B. & Lundgren, J. D. Thin is in?? think again: the rising in?mportance of muscularity in the thin in?deal female body. Sex. Roles. 79, 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0886-0 (2018).

Johnson, C. E. & Petrie, T. A. The relationship of gender discrepancy to eating disorder attitudes and behaviors. Sex. Roles. 33, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01954576 (1995).

Meneguzzo, P. et al. The role of sexual orientation in the relationships between body perception, body weight dissatisfaction, physical comparison, and eating psychopathology in the cisgender population. Eat. Weight Disord - Stud. Anorexia Bulim Obes. 26, 1985–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01047-7 (2021).

Frost, D. M. & Meyer, I. H. Minority stress theory: application, critique, and continued relevance. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 51, 101579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579 (2023).

Meyer, I. H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 (2003).

Soulliard, Z. A., Lattanner, M. R. & Pachankis, J. E. Pressure from within: Gay-Community stress and body dissatisfaction among Sexual-Minority men. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 12, 607–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231186789 (2024).

Nagata, J. M. et al. Sexual orientation discrimination and eating disorder symptoms in early adolescence: a prospective cohort study. J. Eat. Disord. 12, 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01157-y (2024).

Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J. & Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons between mturk, prolific, cloudresearch, qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS One. 18, e0279720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279720 (2023).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was not supported by any specific grant from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, For-mal analysis, Data curation. MP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VCJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. MSL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. NML: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology. GH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. GP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethical approval (Ref. AZ 2022 − 910_1, March 15, 2024) from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, Ruhr University Bochum, East Westphalia site. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brandt, G., Pahlenkemper, M., Jürgensen, V.C. et al. The impact of masculinity and femininity on disordered eating symptoms and the mediating role of muscularity ideals. Sci Rep 15, 32579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19246-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19246-6