Abstract

Behavioral finance and psychology literature consistently show that all investors are susceptible to cognitive biases when making investment decisions. However, their reliance on intuition varies with their level of expertise and funds’ characteristics. In this pre-registered study, we compared professional investors (n = 74) and lay people (n = 244). Participants were presented with four investment funds in a within-subject design where past performance (i.e., positive vs. negative) and typology (i.e., socially responsible vs. traditional) were manipulated. We examined how expertise, the fund’s past performance, and the type of fund influence participants’ assessment of the funds (i.e., emotional reactions, perceived risk, and expected return) and their willingness to sell them. Our findings confirmed that lay people are more influenced by past performance and funds’ characteristics when assessing their emotional reactions and the funds’ risk and return, while expert investors’ assessments remain relatively consistent across conditions. These patterns align with their behavioral intentions. Our results contribute to the understanding of investors’ financial decision-making process and offer practical insights to establish better communication between professionals and their clients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Investing is a complex and demanding task, and investors must consider numerous factors when deciding what to do with their investments. Investment funds indeed vary widely across several dimensions, such as their historical performance and the investment strategy (e.g., ESG, socially responsible funds vs. traditional ones).

To make a decision, investors often rely on observable fund features, such as those mentioned above. Although these features are not as diagnostic of the future value of an asset as some investors, especially lay ones, might think, they elicit clear emotional reactions that can impact how the future performance of the funds is perceived.

Choosing to buy or sell an investment fund is only the last step of a complex decision-making process. Investors often believe that such a process is fully logical and rational and that their decisions are based on objective data. However, psychological literature showed that it is not always the case1,2,3. While financial theory and historical data suggest that the market should reward risk-taking, thus implying a positive correlation between risk and return, in many cases, investors perceive a negative correlation (i.e., low risk associated with high return and vice versa4 and take suboptimal choices because of that.

This type of perception is explained by the affect heuristic1,2,5 and the risk as feeling framework2,5,6. According to this framework, emotional reactions are often the first, intuitive response people experience when facing a stimulus. Emotions are thus postulated to precede and influence a more cognitive assessment of the stimulus, which will in turn influence the behavioral response7,8. Adapted to the financial context, the affect heuristic implies that when investors experience positive emotions toward a fund, they will perceive it as posing low risk and will expect high returns, thus being more prone to choose it. The opposite will happen if the investors experience negative emotions - i.e., they will consider the fund as being risky and expect low expected returns, thus being less likely to choose it (Fig. 1). In these terms, emotional reactions, perceived risk, and expected returns can be highly correlated, but are considered as separate psychological dimensions, each corresponding to an individual stage of the decision to select a fund to invest in9,10,11,12.

Critically, the interplay between emotional reactions, risk and return assessment, and investing decision, as well as the misperception of the financial relationship between risk and expected returns, has been mostly investigated in relation to buying behaviors. To the best of our knowledge, scarce attention has been given to selling decisions. The present work thus aims at filling this gap by exploring how emotional reactions can influence investors’ perception of the risk and expected return of funds they already own in their portfolio, and how those influence the decision to sell them or not.

The first aim of the present study is therefore to investigate how specific fund features - past performance and investment strategy - shape investors’ emotional reactions, impacting the perception of risk and expected return and, in turn, their willingness to sell.

Further, to avoid the complexity of managing their portfolios, many lay investors prefer to rely on professional financial advisors, trusting in their ability to provide unbiased, well-informed recommendations. However, prior research suggests that experts may not be as unbiased as often assumed13,14,15,16,17,18. Priolo et al. (2022)17 for instance, showed that even professional advisors can be biased by their emotional reactions. The second aim of this study is therefore to examine whether the influence of fund characteristics on investment perceptions and intentions differs between lay and professional investors.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial to help investors make better financial decisions and avoid falling prey to their emotional reactions and, potentially, misleading financial advertising. Moreover, insights into how laypeople and professionals weigh these often irrelevant fund features can help improve the effectiveness of the communication between clients and financial advisors.

The role of funds’ features

Emotional reactions towards a fund can be influenced by several aspects, especially ones that are more available in the investors’ mind. A fund’s past performance—whether a fund has gained or lost value—is, for instance, an example of such a readily accessible and easily interpretable piece of information. Despite robust evidence in financial literature disproving its predictive power for future returns19,20,21 many investors continue to rely on historical performance as a proxy for future outcomes22.

When it comes to selling decisions and the impact of past performance, investors often display the disposition effect—a tendency to sell winning assets too early while holding on to losing ones for too long23. Barberis and Xiong24 attribute this behavior to the interplay of two psychological processes. The first, realization utility, refers to the emotional satisfaction derived from locking in gains and the corresponding discomfort associated with realizing losses. The second process, temporal discounting, reflects individuals’ propensity to devalue delayed outcomes25. As a result, investors may prefer to secure a smaller gain immediately rather than wait for a potentially larger future return, while simultaneously deferring the realization of losses to avoid immediate emotional discomfort.

As much as past performance can influence investors’ perception and decisions, the same can be said for the labels associated with an asset or investment strategy. Again, financial theory admonishes that decisions should be made based on fundamental data26 but there is ample evidence that investors can be influenced by labels used to identify an asset27,28. For instance, nowadays many investors choose socially responsible (e.g., ESG) funds. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA, 202329), ESG assets reached approximately $30 trillion in 2022, marking a substantial increase from previous years and is expected to reach $40 trillion by 203030. Such funds are supposed to merge financial returns with ethical, moral ones. This feature makes them appealing to investors and banks. Accordingly, investment companies often market them as the “must-have” product, leveraging on investors’ sustainability values. There is evidence, indeed, that at least some investors are willing to sacrifice performance for morality31. Past work showed that despite the fundamental objective of growing one’s wealth, investors can make decisions based on non-financial goals, e.g., expressive and status ones32,33. For instance, through their investments, people can signal to others (and to themselves) their values or their standing in society. Furthermore, individual investors whose goal is not just to make money but also to be moral are more likely to cope with unsatisfactory outcomes34.

Consistent, investors can choose socially responsible funds both because they are considered better investments or because they are a way to do good. The literature in behavioral finance shows that individual investors have more positive affective reactions towards socially responsible funds than traditional ones, and this impacts the price at which they are willing to sell them when their performance is positive35 - thus going against the disposition effect. However, it is unclear whether this difference in selling decisions is present even when the socially-responsible fund’s performance is negative. It is possible that investors will experience less negative emotions towards a losing socially responsible fund than a traditional one because of the ethical standing of these funds, thus making them less willing to sell it.

Expert vs. lay investors

Reliance on non-diagnostic cues like past performance and type of fund, as well as on the emotional reaction they provoke, should be higher for lay investors as they often lack the analytical tools and expertise available to professionals. In contrast, professional hould more likely recognize the limited diagnosticity of such cues and instead prioritize more relevant information, such as risk metrics or fund management, while keeping their emotional reactions at bay. However, the literature has demonstrated that professional investors can also fall prey to cognitive and emotional biases and decision-making errors13,14,15 although the nature of these errors tends to differ from those observed among individual investors16. For instance, while the reliance on emotional reactions should impact non-expert investors the most, experts may also be influenced by their feelings. The important caveat is that expert investors should be able to use the emotional reactions in a more nuanced fashion. For example, even experts may experience more positive emotions toward a specific type of fund (e.g., a socially responsible one), but their knowledge should allow them to focus on information other than how they feel about it. This would align with previous work17 showing that, even among professional advisors, those with higher expertise are less influenced by their emotions. Again, if professional investors are less likely to use non-diagnostic cues (e.g., feelings and past performance), then they should treat socially responsible investments the same way as traditional ones and focus on what the data say about their potential future performance.

Our study

Participants from a professional financial advisors’ sample (n = 74) and a lay people one (n = 244) were presented with four investment funds in a 2 (Type of Fund: Socially Responsible vs. Traditional) x 2 (Past Performance: Positive vs. Negative) within-subject design. These funds were presented as part of a portfolio owned by participants. Participants’ emotional reactions to the funds, perceived risk, expected return, and willingness to sell (WTS) were assessed as main dependent variables (see Methods section for further details).

First, we aim at investigating how Type of fund, Past performance, and Sample interact in shaping participants’ emotional reactions toward the funds (RQ1). Second, we want to explore how these differences in emotions impact the perception of funds’ risk and expected returns (RQ2). Third, we aim to explore the effect of perceived risk and expected return on WTS (RQ3). Finally, we are interested in exploring whether these three factors (Type of fund, Past performance, and Sample) impact the disposition effect.

Results

Effect of type of fund, past performance, and sample on emotions, risk perception, expected returns, and WTS

We conducted three models (see “Analyses Overview”) to examine the effects of our manipulations on the main dependent variables (see Table 1 for the descriptive analyses): a model including only the main effects, a model including all the two-way interactions, and a model with a three-way interaction. The two-way interaction models were the best-fitting models for all dependent variables based on an Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) weights calculation as in Wagenmakers & Farrell36 (lowest AIC weight = 0.628; see Tables S1-S4 for calculation details), thus have been included in the main text (see Table 2). The models with the main effects and the three-way interaction for each dependent variable are reported in the Supplementary Materials (Table S5). All final models were tested, including demographic information as covariates, and the results did not vary (Tables S6-S9).

Emotions

Our results revealed that participants reported more positive emotions for Socially Responsible (vs. Traditional) funds and for funds with a Positive (vs. Negative) past performance (PP), and that Professionals reported in general more positive Emotions than Lay People. Moreover, the model testing the two-way interactions indicated a significant interaction effect of the Type of Fund and Sample (Table 2). The pairwise comparisons (Fig. 2, panel A), revealed that both Lay People and Professionals perceived higher positive Emotions for Socially Responsible Funds compared to Traditional Funds (Lay People: difference estimate = 1.28, t(959) = 14.19, SE = 0.09, p <.0001; Professionals: difference estimate = 0.66, t(959) = 4.01, SE = 0.16, p =.0004). However, while there was no significant difference in the Emotions perceived for Socially Responsible Funds between the two samples (p = 1.00), Lay People reported significantly lower positive Emotions for Traditional Funds compared to Professionals (difference estimate = −0.87, t(559)= −4.71, SE = 0.18, p <.0001). The estimated marginal means for Emotions were as follows: Lay People and Socially Responsible Fund (M = 7.01, SE = 0.089, 95% CL [6.84, 7.19]); Lay People and Traditional Fund (M = 5.74, SE = 0.089, 95% CL [5.56, 5.91]); Professionals and the Socially Responsible Fund (M = 7.26, SE = 0.161, 95% CL [6.94, 7.57]); Professionals and Traditional Fund (M = 6.60, SE = 0.161, 95% CL [6.29, 6.92]). Finally, the results showed a conditional R2 of 0.42, indicating that 42% of the variance in Emotions was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.15, showing that 15% of the variance was explained uniquely by the fixed effects. The difference between the two R2 values shows the relevance of the interindividual variability and supports our choice for a within-subject design.

Perceived risk

Participants reported higher Perceived Risk for Traditional (vs. Socially Responsible) funds and for funds with a Negative (vs. Positive) PP. We also showed that Professionals (vs. Lay People) reported in general higher Perceived Risk. Results revealed a significant interaction between PP and Sample (Table 2). The pairwise comparisons (Fig. 2, panel B), indicated that while Lay People perceived a higher Perceived Risk for funds with Negative PP compared to Positive PP (difference estimate = − 0.64, t(959) = 7.57, SE = 0.08, p <.0001), Professionals did not show significant difference in Perceived Risk between Negative and Positive PP (difference estimate = 0.18, t(959) = 1.15, p = 1.00). Additionally, Professionals reported significantly higher Perceived Risk than Lay People for both Positive PP (difference estimate = −1.50, t(474) = −7.39, SE = 0.20, p <.0001) and Negative PP (difference estimate = −0.69, t(474) = −3.38, SE = 0.20, p =.0047).

The estimated marginal means for Perceived Risk were as follows: Lay People and Negative PP (M = 5.19, SE = 0.098, 95% CL [5.00, 5.38]); Lay People and Positive PP (M = 4.56, SE = 0.098, 95% CL [4.36, 4.75]); Professionals and Negative PP (M = 5.88, SE = 0.178, 95% CL [5.53, 6.23]) Professionals and Positive PP (M = 6.05, SE = 0.178, 95% CL [5.71, 6.40]). Finally, results showed a conditional R2 of 0.505, indicating that 50.5% of the variance in Perceived Risk was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.086, showing that 8.6% of the variance was explained by the fixed effects only.

Expected returns

Participants reported higher Expected Returns for Socially Responsible (vs. Traditional) funds, and for funds with a Positive (vs. Negative) PP. Professionals (vs. Lay People) reported lower Expected Return, but the difference was not significant. Our results revealed a significant interaction between PP and Sample (Table 2). The pairwise comparisons (Fig. 2, panel C) revealed that while Lay People reported higher Expected Returns for funds with a recent Positive compared to Negative PP (difference estimate = 0.842, t(959) = 11.387, SE = 0.074, p <.0001), Professionals did not (difference estimate = 0.182, t(959) = 1.358, SE = 0.134, p = 1.000). The perception of Expected Returns in the two Samples was not significant for funds with a recent Positive (difference estimate = 0.413, t(509) = 2.512, SE = 0.165, p =.0739) or Negative PP (difference estimate = −0.246, t(509) = −1.497, SE = 0.165, p =.8106). The estimated marginal means for Expected Returns follow: Lay People and Positive PP (M = 7.06, SE = 0.079, 95% CL [6.90, 7.21]); Lay People and Negative PP (M = 6.21, SE = 0.079, 95% CL [6.06, 6.37]); Professionals and Positive PP (M = 6.64, SE = 0.144, 95% CL [6.36, 6.93]); Professionals and Negative PP (M = 6.46, SE = 0.144, 95% CL [6.18, 6.74]). Finally, the results showed a conditional R2 of 0.4350, revealing that 43.5% of the variance in Expected Returns was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.068, showing that 6.8% of the variance is explained solely by the fixed effects.

WTS

Participants reported being higher WTS Traditional (vs. Socially Responsible) funds, and Negative (vs. Positive) PP funds. The two samples did not show differences in the WTS. Results revealed a significant interaction between PP and Sample (Table 2). The pairwise comparisons (Fig. 2, panel D) revealed that while Lay People reported a higher WTS for funds with a Negative vs. Positive PP (odds ratio = 0.494, SE = 0.081, z = −4.316, p =.0001), Professionals did not (odds ratio = 1.505, SE = 0.456, z = 1.350, p = 1.000). All other comparisons were not significant (lowest p =.106). The estimated marginal means for WTS follow: Lay People and Negative PP (M = 0.540, SE = 0.040, 95% CL [0.462, 0.616]); Lay People and Positive PP (M = 0.367, SE = 0.038, 95% CL [0.297, 0.444]); Professionals and Negative PP (M = 0.464, SE = 0.074, 95% CL [0.325, 0.608]); Professionals and Positive PP (M = 0.566, SE = 0.073, 95% CL [0.420, 0.700]). Finally, the results revealed a conditional R2 of 0.494, which shows that 49.4% of the variance in WTS was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.039, showing that 3.9% of the variance was explained by the fixed effects alone.

.

Correlations

We performed correlational analyses to test the relationship between the dependent variables in both samples (Table 3), using Kendall’s Tau, a non-parametric approach that is well-suited for ordinal and not normally distributed data37,38. Results showed that Professionals associated higher Perceived Risk with higher Expected Returns, while Lay People associated lower Expected Returns with higher Perceived Risk. Moreover, Professionals did not rely on Emotions, Perceived Risk, or Expected Returns judgments when deciding whether to sell their financial assets, while Lay People were more likely to sell when they perceived more negative Emotions, higher Perceived Risk, and lower Expected Returns. Finally, higher Expected Returns were associated with more positive Emotions in both samples.

Additional exploratory analyses

Perceived risk and expected return relationship misperception

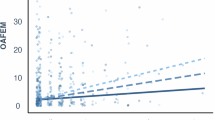

We conducted an additional mixed-effects regression model to investigate the misperception of the correlation between Perceived Risk and Expected Return of financial assets across the two Samples. In our model, we tested the interaction between Expected Return and Sample on Perceived Risk. The results indicated a significant interaction effect (β = 0.57, SE = 0.07, t(1270.0) = 8.30, p <.001; see full regression in Supplementary Table S10). The slope analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that while Professionals did not report a significant effect of Expected Returns on Perceived Risk (p =.440), for Lay People, higher Perceived Risk corresponded to lower Expected Return (estimate = − 0.52, SE = 0.03, p <.0001). The model with Expected Return as the dependent variable led to the same results (see Supplementary Table S11), and including the demographics as covariates did not modify our findings (see Supplementary Table S12). Finally, the conditional R2 of 0.576 of this model indicates that 57.6% of the variance in Perceived Risk was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.194, showing that 19.4% of the variance is explained solely by the fixed effects.

Sample difference in the effect of expected returns on willingness to sell

We conducted a mixed-effects regression model to investigate whether the two Samples were differently influenced by their Perceived Risk and Expected Return when reporting their WTS. Specifically, we tested the two-way interactions between Expected Return, Perceived Risk, and Sample (i.e., Expected Return-Sample, Perceived Risk-Sample) on WTS. The results indicated a significant interaction effect (β = 0.41, SE = 0.14, z = 2.97, p =.003; see full Table in Supplementary Table S13) between Expected Return and Sample. The slope analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that while Professionals did not report a significant effect of Expected Returns on their WTS (p =.78), for Lay People lower Expected Return, corresponded with a higher WTS (β = − 0.44, SE = 0.08, z = − 5.87, p <.0001). The interaction effect between Sample and Perceived Risk was not significant (p =.363). The model testing the effect, including the demographics as covariates, did not modify the findings (see Supplementary Table S14). Finally, the conditional R2 of 0.502 of this model indicates that 50.2% of the variance in Perceived Risk was explained by both the fixed effects and the random intercept, while the marginal R2 was 0.068, showing that 6.8% of the variance is explained solely by the fixed effects.

Discussion

In this pre-registered study, we investigated how fund features (i.e., Past performance: Positive vs. Negative, Type of Fund: Socially-responsible vs. Traditional) influenced investors’ emotional reactions, in turn impacting the perception of financial risk and expected returns, and, as a consequence, WTS, while also exploring potential differences between Lay people vs. Professional investors. The main findings are summarized in Table 4.

Consistent with prior work3,15,22,28,39 results showed that lay investors tend to be greatly biased by emotional reactions and funds’ features when assessing investments. Perhaps reassuringly, professionals seem less impacted by those features. Lay people reported significantly less positive emotions for traditional funds than professionals, although the emotional response to socially responsible funds was similar between groups. Similarly, lay people viewed funds with negative past performance as riskier compared to professionals, but the latter always perceived higher risk (while not making much difference based on past performance). Differences were also detected regarding expected returns, with lay people expecting funds with positive past performance to perform better compared to funds with negative past performance, while past performance did not impact the expectations of the professionals. Notably, these differences between the two samples were also mirrored in their behavioral intentions. In contrast to what professionals did, lay people were more willing to sell funds with negative recent past performance than those with positive ones, thus showing less disposition effect. A possible explanation for these results may be that professionals perceive the information provided in our manipulation as insufficient for a thorough financial assessment and subsequent decision-making. For example, professionals might have viewed one year past performance data as insufficiently reliable, prompting greater caution in their judgments - see for instance the higher perceived risk among this group compared to lay investors. Additionally, they may have been interested in knowing the buying price of the funds or the fund manager, which were not explicitly stated, before deciding whether to sell or not. Such an explanation could account for the absence of an effect of our manipulations on our professional sample overall. Future research should consider providing more comprehensive or varied information about the funds, e.g., longer series for historical data, the buying price, or information about the fund manager. Despite this, it was essential to demonstrate that individuals with varying levels of financial expertise react differently to the information presented, particularly to show that laypeople, but not professionals, used it to inform their decisions on which funds to sell.

Furthermore, our results align with previous literature suggesting that lay investors perceive a negative correlation between risk and expected return, which consequently impacts their investment decisions17 a misperception not evident among professionals. Lay people also reported higher WTS when they perceived lower expected returns (and higher risks), while professionals’ WTS was not influenced by their assessments of risk and returns. These results align with Ganzach4 which showed a negative correlation between risk and expected return only for unfamiliar assets - implying, possibly, that emotions are more important when people lack knowledge of an asset. Consistent, Priolo and colleagues17 found that more expert professional investors perceive a less negative correlation between risk and expected return than less expert ones. Here we extend these findings to the comparison between professionals and lay investors and to selling decisions.

Contrary to previous research32,33,34 we did not observe significant differences in perceptions and WTS between socially responsible and traditional funds. This outcome may be attributed to the increasing popularity of socially responsible funds and the incentives that some banks might offer to advisors for promoting these products, potentially leading to greater familiarity and acceptance among investors. Moreover, socially responsible industries were mixed with more traditional ones in our manipulation. This choice was made to make the socially responsible funds more realistic, but it might have decreased the manipulation effectiveness by adding a confounding effect. Participants might indeed hold different beliefs about the financial outlook of different industries, regardless of the past performance shown in the fund graph, thus leading them to hold personal assumptions about future price movements. Future studies should replicate our design with funds including socially responsible industries exclusively and further investigate whether, and under what circumstances, these funds elicit similar assessments as traditional ones, while also paying attention to investors’ assumptions and beliefs about certain industries.

Furthermore, when evaluating a fund’s performance, investors often compare it to market benchmarks or other funds. However, no benchmark information was provided in our study, and the funds were presented sequentially. Future studies should explore the impact of comparison scenarios, such as by including market benchmarks or testing a joint evaluation condition in which two or more funds are presented simultaneously.

Additionally, our samples differ in size and demographics. The Professionals group is smaller and mainly composed of older, high-income males, possibly explaining the lack of significant results. Still, our findings hold after adjusting for demographics. Additionally, most Lay participants were financially inactive, limiting our ability to account for financial activity. Future research should use more diverse samples and examine whether financially experienced non-professionals resemble active Professionals.

Finally, it is important to remember that our WTS variable does not assess actual behavior, but only intentions. Despite being a common standard in psychology (see for instance40,41,42,43 this shortcoming transfers to our findings, which should thus be considered as merely hypothetical. Future studies should consider testing them in more “real-world” settings, e.g., by using an incentive-compatible design. Moreover, it is important to consider the nature of the financial products used in our study. Mutual funds, indeed, unlike direct stock trading, are professionally managed and provide diversification, reducing the need for individual portfolio decisions. These structural differences may influence investor behavior and should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer some practical insights. We demonstrate that lay people’s decisions are influenced by the emotions elicited by information that is often not useful to assess the future performance of a fund. This might lead investors to make serious mistakes that, when extended to the global scale, can lead to disastrous outcomes, as evidenced by events like the dot.com bubble (mid-90s-early 2000 s) or the subprime mortgage crisis (2007–2009)44. In the dot.com bubble, for instance, the initial global euphoria towards the internet and new technologies made many investors shift their investments toward this “new economy”, with the consequences of huge losses for individual investors and companies worldwide when the bubble eventually collapsed.

Similarly, by showing the distinct ways experts and laypeople perceive and invest in funds, our results point to the importance of properly addressing these differences. Professional advisors must recognize the discrepancies between themselves, the reactions of their non-expert clients, and the actual dynamics of the market. Training programs should thus be developed to increase advisors’ awareness of their clients’ cognitive and emotional biases. This way, they could craft communication strategies that effectively correct misconceptions, thereby improving clients’ understanding of their investment portfolios and options. This approach would not only help clients make more informed and potentially successful investment decisions but could also have positive global ramifications.

Methods

Participants

In this study, we collected data from two different samples, a “Professionals” sample and a “Lay People” one. The Professionals sample included primarily Italian financial advisors recruited through TESEO Srl, an Italian consulting firm, which sent an online questionnaire through their private channels (e.g., mailing list). The Lay People sample instead entailed Italian participants recruited on Prolific and paid 1,65£ each.

Participants who did not provide their informed consent to use their data (n = 119), did not complete the full survey (n = 7), took too long or too short to complete the survey (n = 6), specifically, a third of the median value of the LOI (Length of Interview, i.e., the time spent by the participant to complete the full survey), and participants who did not pass the attentional check (n = 1) were excluded from the analysis.

The final sample comprises 318 participants: 74 Professionals (29.73% female, mean age = 50.31, SD = 12.32) and 244 Lay People (46.7% female, mean age = 31.6, SD = 9.66). Details on participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 5.

Materials and procedure

The study entailed a 2 (Type of Fund: Socially Responsible vs. Traditional) x 2 (Past Performance: Positive vs. Negative) within-subject design, i.e., each participant was presented with all four investment funds in a controlled randomized order. Each participant was presented with the fundamentals (i.e., median risk profile, past and expected sales, expected return of the companies in which the fund was investing) and charts of four different investment funds. Two funds resembled “Socially Responsible Funds” (i.e., funds investing in renewable energy, pharmaceutical, telecommunication, electric cars, real estate, and reduction of toxic waste and harmful emissions), while the other two resembled “Traditional Funds” (i.e., funds investing in automotive, pharmaceutical, petrol, telecommunication, real estate, and raw materials). Moreover, half of the funds showed a recent positive past performance, while the other half showed a negative one. However, to control for a potential effect of a specific trend, two slightly different versions (i.e., different performance variability) of each chart were created and randomly presented between subjects (i.e., each participant was shown only one version of the chart for each of the four funds while fundamentals were kept constant). These funds were presented as part of a portfolio owned by the participants, who were asked to imagine that they invested 10,000 € in each fund in the Milan Stock Exchange. The funds’ performance shown to participants reflected the actual performance of Apple between January 2nd 2022 and December 30th 2022, and of Google between January 3rd 2022 and December 30th 2022. These periods were selected to provide concrete examples of actual market behavior during distinct timeframes. The percentages of returns the participants were presented with, were thus derived from real, unadjusted historical data. The fund’s volatility was calculated using the standard deviation of the returns over the specified timeframes, in line with how volatility is defined and measured in financial analysis. By using real historical data and the standard deviation as the measure of volatility, we ensured that our method reflects the actual variability in the price of the funds during the respective periods. This aligns with standard practices in finance and provides an accurate representation of the fund’s behavior. The funds were presented as having a low risk profile (β = 0.75), a 7.87% increase in sells in the last 12 months, a 7.54% increase of expected returns in the next 12 months and a 9.87% increase in expected sales in the next 12 months. The dependent variables were independently assessed for each fund once they were presented. First, we assessed participants’ emotional reactions (i.e., Emotions) to the investment fund on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (Very negative feeling) to 10 (Very positive feeling). Then, we asked participants to judge the financial risk (i.e., Perceived Risk) and expected return (i.e., Expected Return) of the investment fund on two separate 10-point scale ranging from 1 (Not risky at all/Very low return) to 10 (Extremely risky/Very high return; adapted from Priolo et al.17. Lastly, we assessed participants’ willingness to sell (i.e., WTS) with a “Yes/No” question. Participants who answered “No” were also asked if they were willing to buy (i.e., Willingness to Buy) more shares of that specific fund (“Yes/No”) for exploratory scopes that are not part of the present study. Afterwards, individual differences in financial literacy, trait emotional intelligence, and environmental values were assessed for exploratory scope beyond the present study, using respectively the Financial Literacy Scale45,46the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue-SF47, and the Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PV48. For similar reasons, for Lay people sample mental images associated with “climate change” were assessed at the beginning of the task using a mental imagery task35,49. Lastly, demographic information was collected (i.e., age, gender, political orientation, education, income, being active in finance, and years of activity in the financial sector). All participants provided their informed consent at the beginning of the survey, the Ethical Committee approved the protocol for the Psychological Research of the University of Padova (Protocol #5317) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Data and materials (including the images used to create the charts) are available on the OSF platform (https://osf.io/duzrv/?view_only=8e623cfd18f34c3ab0aea4f3a9bf1f3a). The pre-registration is available here: https://aspredicted.org/h9jj-dctd.pdf.

Analyses overview

We conducted a series of pre-registered linear and logistic mixed-effects regression models, utilizing the ‘lme4’ package in R50. These models enabled us to account for both within-subject and between-subject variability. Moreover, we checked the normality distribution for the tested our main dependent variables for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, the Anderson-Darling Test, and the Q-Q plot, both for the entire sample, and for the two separate samples. Although all variables fell within the acceptable range for skewness and kurtosis (highest skewness = −0.35 and highest kurtosis = 0.53, both for Expected Return), all the p-values were significant (p <.001), indicating a non-normal distribution. For this reason, we used non-parametric tests to perform the analysis. To further explore the interactions, we conducted post hoc pairwise comparisons using the Estimated Marginal Means (EMMs) approach via the ‘emmeans’ package in R51. A Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. Our primary focus was examining the main effects, the two-way and the three-way interaction effects of our two manipulations—Type of Fund (i.e., Socially Responsible vs. Traditional) and Past Performance (i.e., Positive vs. Negative)—in the two samples (i.e., Professionals vs. Lay People) on our main dependent variables: Emotions, Perceived Risk, Expected Return, and WTS. For every model, the variance explained by the mixed-effects model was calculated using the ‘r2()’ function from the R package ‘performance’52.

In addition to our pre-registered analyses, we conducted correlations analyses testing the associations between the main dependent variables in the two samples and two exploratory mixed-effects regression models. One to investigate the differences in the perception of the correlation between Perceived Risk and Expected Return across the two samples, and another to test the effect of Perceived Risk and Expected Return on Willingness to Sell for Professionals and Lay People. These additional analyses aimed to provide deeper insights into how Professionals and Lay People differentially perceive the risk-return trade-off and how their judgments influence their selling intentions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at the OSF repository (https://osf.io/duzrv/?view_only=8e623cfd18f34c3ab0aea4f3a9bf1f3a).

References

Alhakami, A. S. & Slovic, P. A psychological study of the inverse relationship between perceived risk and perceived benefit. Risk Anal. 14, 1085–1096 (1994).

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E. & MacGregor, D. G. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk and rationality. in The Feeling of Risk (ed. Slovic, P.) 16Routledge, London, (2010).

Baker, H. K. & Nofsinger, J. R. Psychological biases of investors. Financial Serv. Rev. 11, 97 (2002).

Ganzach, Y. Judging risk and return of financial assets. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 83, 353–370 (2000).

Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P. & Johnson, S. M. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1, 1–17 (2000).

Hsee, C. K., Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U. & Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 127, 267–286 (2001).

Bechara, A., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 10, 295–307 (2000).

Damasio, A. R. Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain. (Grosset/Putnam, (1994).

Kempf, A., Merkle, C. & Niessen-Ruenzi A. low risk and high return – affective attitudes and stock market expectations. Eur. Financ. Manag. 20, 995–1030 (2014).

Statman, M., Fisher, K. L. & Anginer, D. Affect in a behavioral asset-pricing model. Financial Anal. J. 64, 20–29 (2008).

Lucey, B. M. & Dowling, M. The role of feelings in investor decision-making. J. Econ. Surv. 19, 211–237 (2005).

Rick, S. & Loewenstein, G. The role of emotion in economic behavior. in handbook of emotions (eds. Rozin, P., Haidt, J., McCauley, C. R., Lewis, M. & Haviland-Jones, J. M.) 138–158The Guildford Press, (2008).

Ahmad, Z., Ibrahim, H. & Tuyon, J. Institutional investor behavioral biases: syntheses of theory and evidence. Manage. Res. Rev. 40, 578–603 (2017).

Khare, T. & Kapoor, S. Behavioral biases and the rational decision-making process of financial professionals: significant factors that determine the future of the financial market. J. Adv. Manage. Res. 21, 44–65 (2024).

Shefrin, H. & Statman, M. Behavioral aspects of the design and marketing of financial products. Financ Manage. 22, 123 (1993).

Shapira, Z. & Venezia, I. Patterns of behavior of professionally managed and independent investors. J. Bank. Financ. 25, 1573–1587 (2001).

Priolo, G., Vacondio, M., Bernasconi, S. M. & Rubaltelli, E. Beware the inexperienced financial advisor with a high trait emotional intelligence: psychological determinants of the misperception of the risk-return relationship. Pers. Individ Dif. 188, 111458 (2022).

Vohra, S. & Fenton-O’Creevy, M. Intuition, expertise and emotion in the decision making of investment bank traders. Handb. Res. Methods Intuition. 88–97. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782545996.00015 (2014).

Diacon, S. & Hasseldine, J. Framing effects and risk perception: the effect of prior performance presentation format on investment fund choice. J. Econ. Psychol. 28, 31–52 (2007).

Huang, J., Wei, K. D. & Yan, H. Investor learning and mutual fund flows. Financ Manage. 51, 739–765 (2022).

Huber, C. & Huber, J. Scale matters: risk perception, return expectations, and investment propensity under different scalings. Exp. Econ. 22, 76–100 (2019).

Rubaltelli, E., Agnoli, S. & Franchin, L. Sensitivity to affective information and investors’ evaluation of past performance: an eye-tracking study. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 29, 295–306 (2016).

SHEFRIN, H. & STATMAN, M. The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: theory and evidence. J. Finance. 40, 777–790 (1985).

Barberis, N. & Xiong, W. What drives the disposition effect? An analysis of a long-standing preference-based explanation. J. Finance. 64, 751–784 (2009).

Ruggeri, K. et al. The globalizability of Temporal discounting. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1386–1397 (2022).

Sharpe, W. F. Capital asset prices: a theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk*. J. Finance. 19, 425–442 (1964).

Boyer, B. H. Style-related comovement: fundamentals or labels? J. Finance. 66, 307–332 (2011).

Mullineaux, D. J. & Roten, I. C. Liquidity, labels and medium-term notes. Financial Markets Institutions Instruments. 11, 445–467 (2002).

Global Sustainable Investment Review. 2022 | GSIA. https://www.gsi-alliance.org/members-resources/gsir2022/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Global, E. S. G. assets predicted to hit $40 trillion by 2030, despite challenging environment, forecasts Bloomberg Intelligence | Press | Bloomberg LP. https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/global-esg-assets-predicted-to-hit-40-trillion-by-2030-despite-challenging-environment-forecasts-bloomberg-intelligence/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Berry, R. H. & Yeung, F. Are investors willing to sacrifice cash for morality? J. Bus. Ethics. 117, 477–492 (2013).

Statman, M. The expressive nature of socially responsible investors. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.1094068 (2008).

StatMan, M. Behavioral asset pricing: asset pricing for normal people. J. Portf. Manag. 44, 5–9 (2017).

Rubaltelli, E., Lotto, L., Ritov, I. & Rumiati, R. Moral investing: psychological motivations and implications. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 10, 64–75 (2015).

Rubaltelli, E., Pasini, G., Rumiati, R., Olsen, R. A. & Slovic, P. The influence of affective reactions on investment decisions. J. Behav. Finance. 11, 168–176 (2010).

Wagenmakers, E. J. & Farrell, S. AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon Bull. Rev. 11, 192–196 (2004).

Kendall, M. G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 30, 81 (1938).

Siegel, S. & Castellan, N. J. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (McGraw-Hill, 1988).

Barber, B. M. & Odean, T. The behavior of individual investors. Handb. Econ. Finance. 2, 1533–1570 (2013).

Jansson, M., Beil, A., Andersson, M. & Gärling, T. Investment style and perceived drivers of adoption of socially responsible investment among swedish institutional investors. Sustainable Investment and Corporate Governance Working Papers (2010).

Andersson, M., Gärling, T., Hedesström, M. & Biel, A. Effects on stock investments of information about short versus long price series. Rev. Behav. Finance. 4, 81–97 (2012).

Roos, J. M., Jansson, M. & Gärling, T. A three-level analysis of values related to socially responsible retirement investments. J. Sustainable Finance Invest. 14, 327–343 (2024).

Gärling, T. & Jansson, M. Sustainable investment: consequences for psychological well-being. Sustain. 2021. 13, 9256 (2021).

Quinn, W. & Turner, J. D. Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Lusardi, A. & Mitchell, O. S. The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 52, 5–44 (2014).

van Rooij, M. C. et al. Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. Econ. J. 122, 449–478 (2012).

Petrides, K. V. Psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue). 85–101 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-88370-0_5

Bouman, T., Steg, L. & Kiers, H. A. L. Measuring values in environmental research: A test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 9, 300529 (2018).

Gavaruzzi, T. et al. The role of emotional competences in parents’ vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021. 9, 298 (2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lenth, R. V. et al. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. Preprint at (2020).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Patil, I., Waggoner, P. & Makowski, D. Performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open. Source Softw. 6, 3139 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank TESEO Srl for their invaluable help, and in particular for teaming up with us and sharing the link of our survey with a mailing list of financial advisors. We also thank JDM Lab members for their valuable feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GP, MV, MS, and ER conceptualized the study and created the methodology and materials. All authors ran the data collection. MV, MS and ER ran the formal analysis. GP, MV, MS, and ER wrote the main manuscript text. ER supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giulia, P., Martina, V., Maria, S. et al. Past performance impacts financial judgments and willingness to sell more than types of fund, differences between professionals vs. lay people. Sci Rep 15, 35502 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19313-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19313-y