Abstract

The study aims to present the effectiveness of anomaly detection algorithms in lighting systems based on analyzing records from electricity meters. The road lighting management system operates continuously and in real-time, requiring online anomaly detection algorithms. The paper examines two machine learning-based algorithms: Autoencoder with LSTM-type recurrent neural network and Transformer. The results obtained for these algorithms are compared with a simple mechanism for comparing energy consumption in consecutive periods. Classification metrics such as error matrix, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score were used to evaluate the performance of the algorithms. The analysis showed that the Autoencoder algorithm achieves better accuracy (F1-score = 0.9565) and requires significantly fewer computing resources than the Transformer algorithm. Although less efficient (F1-score = 0.8125), the Transformer algorithm also demonstrates the ability to detect anomalies in the road lighting system effectively. Implementing the Autoencoder algorithm on an actual ILED platform allows anomaly detection with a delay of 15 min, which is sufficient to take corrective action. The conclusions of this study indicate the significant advantage of machine learning-based algorithms in anomaly detection in lighting systems, which can significantly improve the reliability and efficiency of urban lighting management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article follows the experimental selection and implementation of a fault detection algorithm for a street lighting system that analyzes records from electricity meters. Algorithms were implemented and developed within the framework of the realized R&D project INFOLIGHT Edge Device control platform. Thanks to its modular architecture, the platform is open and scalable, making it possible to implement controllers for various elements of the lighting network.

The road lighting management system operates continuously and in real-time. The monitoring function of lighting system components should, among other things, identify new or unknown events - anomalies that may indicate a failure. Machine learning for monitoring involves training the model with data from current observations and then identifying deviations in events or measurement results based on unlabeled data; that is, it requires a self-learning algorithm. It is required that the anomaly detection algorithm operates in real-time, online, meaning that anomalies must be detected within a limited period after they occur, allowing system managers to take preventive or corrective action as soon as the anomaly becomes apparent.

The definition of the concept of anomaly, its various manifestations, and its typology are presented in the papers1,2. Ways of automatic detection of anomalies in lighting systems are known from the literature, but the literature on urban lighting is not particularly extensive. The introduction of Smart Meters and Advanced Metering Infrastructure AMI (Advanced Metering Infrastructure) has enabled a range of mechanisms called non-intrusive load monitoring (NILM). This allows detailed energy monitoring by observing only aggregate energy consumption. An overview of NILM approaches, systematics of methodologies, and comparisons of experiments are presented in the article3. In article4, a model-agnostic hybrid framework for NILM applications in sustainable smart cities was proposed. The use of deep learning techniques has become increasingly popular in data analysis due to its ability to extract hidden relationships and uncover complex relationships, as discussed, for example, in the paper5. Data collected from Smart Meters provides valuable information about consumer behavior, allowing energy consumption profiling, forecasting, and anomaly detection. An overview of the methods of modeling the electricity load profiles in residential buildings is presented in the paper6. Methods for forecasting energy consumption based on Smart Meters are included in another paper7.

Recent studies on anomaly detection in energy systems have explored various approaches, each with distinct contributions and limitations. For instance, Himeur et al.8 proposed an artificial intelligence-based anomaly detection framework for building energy consumption, achieving high accuracy (F1-score ≈ 0.90) using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). However, their approach relies on high-resolution data, which increases computational demands and makes it less suitable for resource-constrained edge devices. Kaymakci et al.9 applied LSTM-based autoencoders for anomaly detection in industrial systems, demonstrating robustness to noise (F1-score ≈ 0.88), but their models require extensive training.

Training is limited in scenarios with limited historical data, such as newly installed urban lighting systems. Wen et al.10 introduced Transformer-based models for time-series forecasting, leveraging self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies. Yet, their high computational complexity (execution times > 1 h on edge devices) hinders real-time deployment. Unlike these works, our study focuses on optimizing Autoencoder and Transformer models for low-power edge devices in urban lighting systems, achieving high accuracy (F1-score = 0.9565 for Autoencoder) with reduced computational requirements (14-min execution time) and minimal training data (3 days). This addresses a critical gap in real-time, resource-efficient anomaly detection for smart urban infrastructure, where prior methods either lack scalability or demand excessive computational resources.

Anomalies in energy consumption can be caused by changes in user behavior, weather conditions, equipment failures, data set errors, and human error11. Anomalies can also occur due to intentional criminal tampering with AMI infrastructure and manipulation of smart meter readings12. Anomaly detection based on data from Smart Meters has been tested for diverse types of consumers, industry, including residential13, commercial buildings8, and industrial9. A wide range of anomaly detection applications based on Deep Learning is included in the article14. Articles2,15,16 discuss various anomaly detection algorithms in the time series. Various anomaly detection models in time series for industrial systems were examined in the paper17, where, among other things, the effect of the size of the learning set on anomaly detection models was analyzed. In the article18, deep learning methods are applied to short-term load forecasting. Anomaly detection in a road lighting system from Smart Meter data, based on ARIMA regression models and a recurrent neural network, was analyzed in19. The article20 examined algorithms based on the deep learning method, utilizing the Autoencoder model with LSTM and 1D Convolutional networks.

Recently, many publications have been on the applications of Transformers21 in machine learning. Transformers as a deep learning architecture have made tremendous progress in various applications, such as natural language processing22, image recognition23, and time series analysis10,24. Transformers are characterized by their ability to detect long-range dependencies and interactions through a self-attention mechanism. Transformers do not use recursion, thus requiring less training time than recurrent neural architectures such as LSTM. Transformers use position encoders (positional encoders). The paper25 proposes a transformer-based multi-stage prediction model. A lot of work is devoted to accelerating computational activities and reducing memory requirements26,27,28, which is essential in Edge Computing applications.

The novelty of this work lies in the adaptation and optimization of Autoencoder (AE) models, combined with LSTM and Transformer models, for real-time anomaly detection in urban lighting systems on resource-constrained edge devices. Unlike prior applications of these models in high-resource environments (e.g8,9,10, we introduce specific enhancements:

-

1.

A lightweight AE architecture with a single- or two-layer LSTM configuration, minimizing computational overhead (14-min execution time);

-

2.

A simplified Transformer model with reduced encoder layers (2 layers) and dropout tuning (0.1 and 0.5) to balance accuracy and speed; and (3) a sliding window methodology tailored for minimal training data (3 days), enabling rapid deployment in dynamic urban settings. These adaptations address the research gap in scalable, low-power anomaly detection, achieving a superior F1-score of 0.9565 for the AE model compared to traditional methods (e.g., ARIMA19, F1-score unavailable but lower accuracy implied) and baseline energy comparison (F1-score = 0.7059).

Anomaly detection system

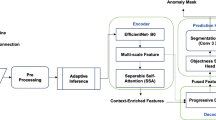

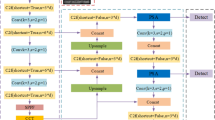

The configuration of the anomaly detection system used for research experiments based on power measurements in the street lighting control cabinet is shown in Fig. 1. The Smart Meter records instantaneous power for each phase separately. A group controller (hub) installed in the control cabinet communicates with the meter via an RS-485 serial port with MODBUS protocol. The Data Logger module is responsible for continuously reading the meter data at a set frequency. The data is stored in a local relational database supporting SQL. The management system agent synchronizes the records from the local and central databases. The module responsible for anomaly detection reads Smart Meter records from the local database, performs analysis, and sends information about the event through the Management System Agent module if an anomaly is detected.

Under real-world conditions, the platform on which the algorithms are run has limited computing resources. This is related to both energy and environmental constraints. This must be considered when designing an anomaly detection algorithm. Another limitation of algorithms based on machine learning is the training time, which should take a manageable amount of time to ensure the algorithm’s readiness to start working. In the configuration described above, the usability of two algorithms for detecting anomalies in Smart Meters’ online energy meter records based on machine learning using artificial neural networks was evaluated. The first algorithm utilizes a Transformer architecture, while the second employs an Autoencoder architecture with a recurrent neural network of the LSTM type. In addition, the effectiveness of these algorithms was compared with an algorithm based on a simple mechanism for comparing energy consumption in two consecutive periods. Confusion Matrix calculus and classification statistics metrics were used to compare the algorithms.

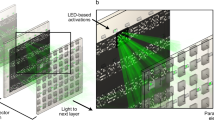

The configuration of the controller used in the calculations is shown in Fig. 2. A controller was configured to act as a network hub in the application under study. The ILED controller used in the experiments is a custom-designed edge device housed in a standard Zhaga Book 18 enclosure, equipped with a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M4 processor (120 MHz, 1 MB flash, 256 KB RAM). It lacks a dedicated machine learning accelerator, relying solely on CPU based computation, which reflects the resource constraints typical of urban lighting control cabinets. The controller communicates with the Smart Meter via an RS-485 serial port using the MODBUS protocol and stores data in a local SQL database, ensuring scalability and compatibility with existing infrastructure.

Anomaly detection methodology

For both machine learning-based algorithms, the following method of operation was adopted. The observation starts with the normal state of the observed signal, then the required amount of data is collected, which is used to train the model, and the subsequent data read from the counter is treated as test data. The difference between the prediction deduced from the model and the actual data can indicate the occurrence of an anomaly. The values of recorded data from energy meters are continuous, so the prediction error also has continuous values; that is why it is necessary to define a threshold value that will make the results of the algorithm be classified as positive or negative, depending on whether the resulting value is higher or lower than the threshold value. Such an anomaly detection algorithm is a binary classification method in which a distinction is made between two classes of observations: normal and abnormal. The threshold selection is one of the steps of a specific implementation, depending on the requirements. This article will use two methods of determining the threshold to compare algorithms. The first maximizes the difference between sensitivity and false positive rate in a diagnostic test, whereas the second balances precision with recall.

The Rolling Window method makes the algorithm run in real-time. For road lighting systems, the primary observation period is a day, so the test period is 24 h, and the training period is a multiple of this. The idea of the method adopted in this article is shown in Fig. 3. The window is shifted by a time interval S equal to 24 h, so the detection of the example anomaly should happen in the fourth step of the algorithm’s operation.

The resolution of the algorithm can be increased by decreasing the value of the window offset S. The minimum value of the offset S is the observation period of the energy meter measurements, in the present case, it is 15 min. Decreasing the value of the window offset will increase the frequency of calculations and, thus, the demand for computing power. The offset size should be related to the expected response time to the detected anomaly.

The sliding window method in anomaly detection is related to the requirement to restart the algorithm after detecting an anomaly. It is then necessary to start collecting data from scratch so that data containing the anomaly is not used to train the model. Literature1 distinguishes diverse types of anomalies: point, contextual, and collective. For time series analysis, it is also important to determine the duration of the anomaly. The first case is a unitary anomaly, which lasts for a finite period, and when it ends, the input data returns to the pattern before the anomaly occurs. Example waveforms corresponding to this type of anomaly are shown in Fig. 4. The second case is a Change Point or a point in time at which the statistical properties of a time series change significantly. Change Point means a permanent change in the character of the input data; after its occurrence, the data readings will already have a new character. The issue of Change Point is discussed in the works29,30, among others. Figure 5 shows example waveforms corresponding to such anomalies.

In real-world applications, various strategies can be adopted to respond to the occurrence of a Change Point. However, this article does not cover this aspect.

Model optimization for edge devices

.To ensure the Autoencoder and Transformer models are suitable for resource-constrained edge devices, we implemented several optimizations. For the Autoencoder, we designed a lightweight architecture with one or two LSTM layers (Table 3), reducing the parameter count to 32 output space units, which lowers memory usage and enables execution in 14 min on the ILED platform (Table 10). The Transformer model was simplified by limiting the number of encoder layers to 2 and testing dropout rates (0.1 and 0.5) to prevent overfitting while maintaining computational efficiency (30-min execution time). Both models use min–max normalization and a sliding window approach with a 15-min resolution, optimized for the standard energy metering interval, balancing detection speed and accuracy. These adaptations ensure real-time performance on edge devices with limited CPU resources (e.g., ILED controller with no machine learning accelerator).

Hyperparameter tuning

Hyperparameter tuning was performed to optimize the Autoencoder and Transformer models for accuracy and computational efficiency on the ILED platform. For the Autoencoder, we adopted hyperparameters from20, which were validated for power consumption anomaly detection, including an output space of 32, sequence length of 96 (corresponding to one day at 15-min resolution), and the Adam optimizer with Mean Absolute Error (MAE) loss function (Table 3). To ensure robustness, we tested batch sizes of 1, 2, and 4, selecting a batch size of 1 to minimize memory usage on edge devices. The “early stopping” method was employed, monitoring MAE with a minimum delta of 0.0001 and a patience of 50 epochs (max 500 epochs), to prevent over-fitting and reduce training time. For the Transformer, we conducted a grid search over key hyperparameters: number of encoder layers (1, 2, 3), number of attention heads (8, 16, 32), and dropout rates (0.1, 0.5). The configuration with two encoder layers, 16 attention heads, and a dropout of 0.1 yielded the best F1-score (0.8125) with a 3-day training period (Table 9). The ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler (factor = 0.5, patience = 3) was used to adjust the learning rate dynamically, ensuring convergence within 50 epochs. These tuning strategies balanced model performance with the computational constraints of the ILED platform, enabling efficient anomaly detection.

Data description

Data from a lighting control system installed in a Polish city was used to test the algorithms. Data from meters were read within 60-second periods; then, down sampling was applied to 15-min fragments by calculating the average value over the period. One observation period is 96 readings of active power values. The annotated test data set consists of sequences of readings of energy meter records, representing multiples of observation periods ranging from 1 to 27 days in length. Each sequence consists of regular periods and ends with the occurrence of a period with an anomaly. The observation period is classified from the beginning to the end of the day. If an abnormal phenomenon occurs during this period, it is labeled as an anomaly. There are 35 sequences in the test set; the total amount of labeled data is 455 multiples of a single observation period. Thus, the test set is unbalanced, containing 35 occurrences of class 1 corresponding to anomalies and 422 occurrences of class 0. Equal proportions of the abundance of the two classes would hardly correspond to real situations in which anomalies do not occur very often. Sample test data records are shown in Fig. 6.

Algorithm based on energy comparison

One of the simplest methods for detecting anomalies in the energy consumption of intermittent consumers, such as a road lighting system, is to compare energy consumption over two consecutive periods. The absolute value of the difference exceeding a preset threshold may indicate an anomaly. This method is described by Eq. (1):

where Ei energy for the measurement period under study, T - decision threshold. The natural measurement period for a road lighting system is 24 h because it operates daily, according to dusk and dawn.

Using the method described above, calculations were made for the test data. The Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) and the Precision-Recall Curve (PRC), shown in Fig. 7, were determined.

The values of optimal decision thresholds were calculated according to two methods. The first method maximizes the difference between TPR - True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) and TNR - True Negative Rate. The second method balances Precision (PPV - Positive Predictive Value) with Recall (TPR - True Positive Rate) by maximizing the F1-score31. The results for both methods and the Area Under Curve (AOC) values for the ROC curve and PRC are included in Table 1.

However, other threshold selection criteria must be considered for the energy records of the road lighting system. In the energy records of the road lighting system in two consecutive periods, there will be a difference due to the varying night duration. The change in the night duration varies for different seasons and different latitudes. Still, the maximum value, occurring at the border of the Arctic circle, does not exceed 8 min32, which means that the change in energy consumption resulting from this is less than 0.01. The detection threshold should be higher than this value. The value of the threshold is strictly related to the measurement accuracy of the energy meter; for a meter of accuracy class 1, the accuracy is ± 1%, so the threshold should not be less than 0.02. The test data was recorded with meters of such accuracy class, so a threshold of 2% was used to determine the error matrix table. The results of calculating confusion matrix metrics for this threshold and the thresholds mentioned above are shown in Table 2.

It is worth noting that the threshold determined based on the accuracy of the meter does not give significantly worse results than the threshold based on the method of the F1-score maximization.

Autoencoder-based algorithm

Models based on a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) recurrent neural network (RNN) were selected to analyze an algorithm based on an artificial neural network like Autoencoder (AE). A single-layer model consisting of a decoder and encoder and a two-layer model with an additional hidden layer were evaluated. Other model parameters are shown in Table 3.

The input data is subjected to min-max normalization before AE processing. The size of the training set was 288 measurements or 3 days. The training set was divided into a learning set and a validation set in a ratio of 2:1. The test set covered 2 days, or 192 measurements. The input data for the LSTM network requires conversion from a T ×1 matrix where T - is the number of measurements to an N × S matrix, where N - is the number of sequences S - the sequence length. For S = 96, the number of sequences for the training set equals 193; for the test set, it is 97. This size of the training and test sets means that the algorithm requires the collection of measurements over at least 4 days to start detection.

The model is trained using the “early stopping” training method. After pilot experiments, MAE was adopted to monitor model performance, with a minimum rate change of 0.0001, several epochs with no rate change of 50, and a maximum number of epochs of 500.

After training, a prediction is determined for the training set. For this prediction, an error function vector for each sequence is calculated based on Eq. (2), and then the average value is calculated according to Eq. (3):

In the next step, the prediction for the test set is determined, and the error function vector and the mean value of the error function vector are calculated. The comparison of the mean value of the error function vector for the test set and the training set is used to detect anomalies, as described in Eq. (4):

An alternative method for detecting anomalies is to determine the variance of the error function vector for the test and training set based on Eq. (5). Comparison of the variance of the error function vector can also be used to detect anomalies as described in the rule set as in Eq. (6):

Using the methods described above, calculations were performed for the test data for the single-layer (1 L) and two-layer (2 L) models, using both detection based on a comparison of the average value (AVG) and variance (VAR) of the error function vector. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and PRC curve were determined, as shown in Fig. 8. Table 4 shows the calculated AOC values for the ROC and PRC curves the values of optimal decision thresholds according to the methods described above.

The results show the advantage of the two-layer model and the superiority of the method based on using a variance error function vector for variance detection (VAR).

The results of calculating confusion matrix metrics for the designated thresholds are shown in Table 5.

Transformer-based algorithm

A basic transformer architecture (Vanilla Transformer) was used to analyze the anomaly detection algorithm20. The most important parameters of the model are shown in Table 6.

The input data undergoes min-max normalization before processing. The model generates a single value for the input sequence. Thus, to obtain a prediction vector for a measurement period, 96 sequences need to be generated. Therefore, the minimum size of the learning and validation sets is 192 measurements or 2 days. This means that analogous to the Autoencoder algorithm, a minimum of 4 days of collection of measurements are required until detection begins. Calculations were also made for a training period equal to 3 days, resulting in 5 days of measurement collection. For both cases, the test collection contained 2 days of measurements.

During learning, a mechanism was used to reduce the learning rate when the metric stopped improving (ReduceLROnPlateau); reduction parameters: mode ‘min’, factor = 0.5, patience = 3. The model is trained with a fixed number of epochs equal to 50.

After training, the prediction for the training set is determined. The error is calculated for each sequence based on Eq. (7), and then the mean value is calculated according to Eq. (3) and the variance according to Eq. (5):

Next, the procedure is identical to that for the algorithm using the Autoencoder; one determines the prediction for the test set and calculates the mean value and variance of the error function vector. Equation (4) for the mean value or Eq. (6) for the variance is used for detection, respectively.

Using the above methods, calculations were performed for two different dropout regularization parameters: 0.1 and 0.5. Analogous to the Autoencoder algorithm, detection based on comparison of the average value (AVG) and variance (VAR) of the error function vector was used. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and PRC curve were determined, shown in Fig. 9 for a 2-day and Fig. 10 for a 3-day learning period.

Table 7 shows the calculated AOC values for the ROC and PRC curves and the values of optimal decision thresholds according to the methods described above.

The results of calculating Confusion Matrix metrics for the designated thresholds are shown in Table 8 for the 2-day period and in Table 9 for the 3-day period.

Analysis of the computational results shows that the Dropout parameter does not significantly affect the results, indicating that, in contrast to the Autoencoder algorithm, the mean value method of the error function vector is more favorable from a detection point of view. Increasing the training period slightly improved the Confusion Matrix metrics.

Comparison of algorithms efficiency

The algorithm based on energy comparison (subsection 3.2) and variants of the Autoencoder (3.3) and Transformer (3.4) algorithms that achieved the best Confusion Matrix F metric1 -score were implemented on an actual network hub controller based on the developed ILED control platform. For the Autoencoder, the selected variant is a two-layer model with detection based on error function vector variance comparison. For the Transformer, the chosen variant is Dropout = 0.1 with detection based on a comparison of the mean of the error function vector, with a 3-day learning period. Average execution times for a single measurement window were measured for these three algorithms. The calculations were performed on the CPU alone, without machine learning accelerator support. The results are included in Table 10.

From the comparison of calculation times, the Autoencoder-based algorithm has a definite advantage over the Transformer-based algorithm. Not only is the execution time twice as fast, but also the CPU utilization is significantly lower. It should be noted that both algorithms based on neural networks allow moving the measurement window by less than 24 h. Table 11 shows a comparison of Confusion Matrix metrics for the tested algorithms.

To evaluate the proposed Autoencoder and Transformer models against recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches, we compare their performance with methods from related studies on energy anomaly detection. Himeur et al.8 reported an F1-score of approximately 0.90 using CNNs for building energy anomaly detection, but their approach requires high-resolution data and extended computation times (> 1 h), unsuitable for edge devices. Kaymakci et al.9 achieved an F1-score of 0.88 with LSTM-based autoencoders in industrial applications, but their method demands large training datasets (weeks of data), limiting their use in dynamic urban settings. Wen et al.10 applied Transformers for time-series forecasting, achieving high accuracy but with execution times exceeding 1 h on edge devices due to model complexity. In contrast, our Autoencoder model achieves an F1-score of 0.9565 with a 14-min execution time on the ILED platform, outperforming these SOTA methods in both accuracy and computational efficiency for urban lighting applications. The energy comparison baseline (F1-score = 0.7059) and ARIMA-based approach19 (F1-score unavailable but lower accuracy implied) were included as they represent standard practices in urban lighting systems, providing a practical reference for real-world deployment. These comparisons demonstrate our approach’s superior balance of accuracy and efficiency in resource-constrained environments.

The comparison of results clearly shows the superiority of the Autoencoder algorithm over the Transformer algorithm and the energy comparison algorithm. A graphical comparison of the F1 score, execution times, and measurement collection time is presented in Fig. 11.

Conclusions

This paper demonstrates that an algorithm based on the Transformer architecture is suitable for detecting anomalies in a road lighting system. A neural network based on the basic Transformer model that can detect anomalies is defined. The algorithm works even for a 4-day collection period of measurements.

It has also been shown that the algorithm based on the Autoencoder architecture achieves better accuracy and requires much less computational effort than the Transformer algorithm. Implementing the Autoencoder-based algorithm on a real platform can detect anomalies with as much as a 15-min delay, which goes beyond real-world needs, as this is well below expected failure response times. In addition, the algorithm based on the Autoencoder architecture achieves better accuracy than a method based on a simple energy comparison mechanism.

We can expand on the Autoencoder (2-layer, LSTM-based) and Transformer (Vanilla architecture) implementations to enhance transparency and reproducibility. For the Autoencoder, key hyperparameters include a 32-unit output space, sequence length of 96, and MAE loss with Adam optimizer (Table 3), trained via early stopping over 500 epochs. The Transformer uses 128 input features, 16 attention heads, and a dropout of 0.1 or 0.5 (Table 6), with a fixed 50-epoch training schedule and ReduceLROnPlateau. Data preprocessing involves min-max normalization, and anomaly detection leverages variance (Autoencoder) or mean (Transformer) of error vectors, with thresholds optimized via ROC/PRC analysis.

Our results outperform simpler methods like ARIMA-based detection19, F1-score unavailable but lower accuracy implied) and prior Autoencoder applications20, no real-time focus). Compared to the energy comparison baseline (F1-score = 0.7059), our Autoencoder achieves a 35% higher F1-score (0.9565) and detects anomalies in 15 min versus 24-hour delays in traditional methods. The Transformer (F1-score = 0.8125), while effective, is less efficient (30-min execution) than the Autoencoder (14 min), highlighting the latter’s advantage in accuracy and speed (Table 11). This positions our approach as a practical advancement over existing NILM and time-series anomaly detection techniques3,14.

The measurement collection time for algorithms based on machine learning is relatively long and reducing it will significantly increase the usability of the algorithm, which will be the subject of the planned research. Algorithm tests were conducted on test data with a single anomaly after a variable period of regular behavior. The behavior of the algorithms for sequences with several anomalies has not been studied, which will also be the subject of further work. It is also planned to study different strategies to respond to the occurrence of Change Point.

Regardless of plans to expand the scope of experiments, the results obtained so far already find useful applications in automatic anomaly detection in road lighting systems.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this article are available in the Kaggle repository INFOLIGHT SmartMeters DB, Version 4, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tosmial/infolight-sm.

References

Foorthuis, R. On the nature and types of anomalies: A review of deviations in data. Int. Journ Data Sci. Analytics. 12 (4), 297–331 (2021).

Schmidl, S., Wenig, P. & Papenbrock, T. Anomaly detection in time series: A comprehensive evaluation. Proc. VLDB Endow. 15 (9), 1779–1797 (2022).

Schirmer, P. A. & Mporas, I. Non-intrusive load monitoring: A review. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 14 (1), 769–784 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. On enabling collaborative non-intrusive load monitoring for sustainable smart cities. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 6569 (2023).

Elahe, M. F., Jin, M. & Zeng, P. Review of load data analytics using deep learning in smart grids: Open load datasets, methodologies, and application challenges. Int. Journ Energy Res. 45 (10), 14274–14305 (2021).

Proedrou, E. A comprehensive review of residential electricity load profile models. IEEE Access. 9, 12114–12133 (2021).

Dewangan, F., Abdelaziz, A. Y. & Biswal, M. Load forecasting models in smart grid using smart meter information: A review. Energies 16 (3), 1404 (2023).

Himeur, Y., Ghanem, K., Alsalemi, A., Bensaali, F. & Amira, A. Artificial intelligence based anomaly detection of energy consumption in buildings: A review, current trends and new perspectives. Appl. Energy. 287, 116601 (2021).

Kaymakci, C., Wenninger, S. & Sauer, A. Energy anomaly detection in industrial applications with long short-term memory-based autoencoders. Procedia CIRP. 104, 182–187 (2021).

Wen, Q. et al. Transformers in time series: A survey. Preprint: arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.07125 (2022).

Oprea, S. V. & Bâra, A. Feature engineering solution with structured query Language analytic functions in detecting electricity frauds using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 3257 (2022).

Syed, D., Abu-Rub, H., Refaat, S. S. & Xie, L. Detection of energy theft in smart grids using electricity consumption patterns. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) 4059–4064 (IEEE, 2020).

Wang, X. & Ahn, S. H. Real-time prediction and anomaly detection of electrical load in a residential community. Appl. Energy. 259, 114145 (2020).

Ruff, L. et al. A unifying review of deep and shallow anomaly detection. Proc. IEEE. 109 (5), 756–795 (2021).

Choi, K., Yi, J., Park, C. & Yoon, S. Deep learning for anomaly detection in time-series data: Review, analysis, and guidelines. IEEE Access. 9, 120043–120065 (2021).

Braei, M. & Wagner, S. Anomaly detection in univariate time-series: A survey on the state-of-the-art. Preprint: arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.00433 (2020).

Kim, B. et al. A comparative study of time series anomaly detection models for industrial control systems. Sensors 23 (3), 1310https://doi.org/10.3390/s23031310 (2023).

Wen, X., Liao, J., Niu, Q., Shen, N. & Bao, Y. Deep learning-driven hybrid model for short-term load forecasting and smart grid information management. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13720 (2024).

Smialkowski, T. & Czyzewski, A. Detection of anomalies in the operation of a road lighting system based on data from smart electricity meters. Energies 15 (24), 9438. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249438 (2022).

Smialkowski, T. & Czyzewski, A. Autoencoder application for anomaly detection in power consumption of lighting systems. IEEE Access. 11, 124150–124162. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3330135 (2023).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), December 4–9, Long Beach, CA, USA (2017).

Wolf, T. et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations 38–45 (2020).

Khan, S. et al. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR). 54 (10s), 1–41 (2022).

Wu, N., Green, B., Ben, X. & O’Banion, S. Deep transformer models for time series forecasting: The influenza prevalence case. Preprint: arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08317 (2020).

Li, M., Chen, Q., Li, G. & Han, D. Umformer: A transformer dedicated to univariate multistep prediction. IEEE Access. 10, 101347–101361 (2022).

Katharopoulos, A., Vyas, A., Pappas, N. & Fleuret, F. Transformers are rnns: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning 5156–5165 (PMLR, 2020).

Zhuang, B. et al. A survey on efficient training of transformers. Preprint: arXiv:2302.01107 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Enhancing the locality and breaking the memory bottleneck of transformer on time series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. Vol. 32 (2019).

Apostol, E. S., Truică, C. O., Pop, F. & Esposito, C. Change point enhanced anomaly detection for IoT time series data. Water 13 (12), 1633 (2021).

Touzani, S., Ravache, B., Crowe, E. & Granderson, J. Statistical change detection of Building energy consumption: Applications to savings estimation. Energy Build. 185, 123–136 (2019).

Lipton, Z. C., Elkan, C. & Naryanaswamy, B. Optimal thresholding of classifiers to maximize F1 measure. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2014, Nancy, France, September 15–19, 2014. Proceedings, Part II 14 225–239 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

Calculator, N. O. A. A. S. & Sunrise, F. Sunset, solar noon and solar position for any place on earth. https://gml.noaa.gov/grad/solcalc/, Accessed on 01 Jul 2024.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR) through the European Regional Development Fund titled “INFOLIGHT-Cloud-Based Lighting System for Smart Cities” under Grant POIR.04.01.04-00-0075/19-00.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S.: planning, data collection, methodology, algorithm implementation, testing, data analysis, drafting of paper content. A.C.: the study concept, supervision, mentoring, reviewing, and collaborative editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Śmiałkowski, T., Czyżewski, A. Anomaly detection in urban lighting systems using autoencoder and transformer algorithms. Sci Rep 15, 35972 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19414-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19414-8