Abstract

Caregivers of individuals with chronic psychiatric disorders are frequently exposed to high subjective burden, which may undermine their psychological resilience. Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI), particularly its self-control facet, has been proposed as a protective factor; however, the mechanisms linking caregiver burden, self-control, and resilience are not well established. This cross-sectional study investigated whether self-control mediates the relationship between caregiver burden and psychological resilience among psychiatric caregivers in Oman. A total of 187 caregivers attending a tertiary outpatient clinic completed validated Arabic versions of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Short Form (TEIQue-SF), the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), and the Zarit Burden Interview–Short Form (ZBI-12). Mediation analysis was conducted using 5,000 bootstrap resamples, adjusting for sociodemographic variables. Higher caregiver burden was significantly associated with lower self-control (β = –0.28, p = 0.002), and higher self-control was significantly associated with greater resilience (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of burden on resilience via self-control was statistically significant (β = –0.15, 95% CI: –0.24 to –0.07), whereas the direct effect was non-significant after accounting for self-control, consistent with full mediation. These findings suggest that self-control may play a mediating role in the relationship between caregiver burden and resilience. Interventions targeting emotion-regulation skills could potentially enhance resilience among psychiatric caregivers, however longitudinal studies are needed to establish causal pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caring for individuals with chronic psychiatric conditions is both a meaningful and demanding responsibility. Caregivers frequently experience emotional exhaustion, physical fatigue, and psychological distress—challenges that can persist over time and adversely affect overall well-being1,2. In collectivist societies such as Oman, caregiving is often regarded not merely as a familial obligation but as a moral duty deeply embedded in cultural and religious norms3. Despite the high value placed on caregiving, the role is associated with considerable personal costs. Caregiver burden refers to the cumulative stress experienced by individuals who provide long-term care to chronically ill family members4. This burden often manifests as emotional strain, social withdrawal, and deterioration in both physical and mental health5,6.

Caregiver burden is the subjective appraisal of stress from caregiving demands (Intrieri & Rapp, 1994). Self-control (TEIQue self-control facet) is a trait-like capacity for inhibitory emotion regulation and impulse control—relatively stable yet trainable7. Resilience is a capacity to bounce back from stress, treated here as modifiable rather than a fixed trait8.

This study examines whether higher caregiver burden is associated with lower self-control and whether lower self-control is associated with lower psychological resilience. We focus on self-control—a facet of trait emotional intelligence (TEI) as the statistical bridge between burden and resilience. While the adverse effects of caregiver burden are well documented, it remains unclear why some caregivers maintain psychological well-being while others succumb to distress. This question has prompted researchers to investigate personal capacities that may serve as protective factors9. One such capacity is resilience, broadly defined as the ability to adapt to and recover from adversity10. Within the caregiving context, resilience is linked to adaptive responses to daily stressors, constructive coping during crises, and better long-term stability11. The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)8, for example, conceptualizes resilience as the ability to “bounce back” from difficulty—a capacity particularly salient for individuals engaged in high-stress, emotionally taxing caregiving roles6.

The relevance of resilience to caregiver outcomes can be further understood through Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model of stress and coping, which posits that psychological outcomes are shaped by the interaction between external stressors and internal coping resources. However, resilience may not act in isolation. Emerging evidence suggests that its protective influence can be strengthened by other psychological capacities, particularly emotional intelligence12. Research from lung cancer caregiving, one of the few rigorous meta-syntheses available, indicates that caregivers often experience emotional strain, shifting family roles, and a substantial need for informational and social support13. Evidence from other illness contexts further shows that trait emotional intelligence and gender can influence caregiver well-being, functioning either as protective or risk factors. For instance, emotional intelligence has been found to mediate the relationship between maternal attachment and anxiety in youth, with gender moderating this effect. These findings suggest that similar dynamics may also operate among adult caregivers14.

Emotional intelligence (EI) refers to the ability to perceive, manage, and utilize emotions effectively15. Trait emotional intelligence (TEI), as proposed by Petrides (2009), views EI as a constellation of emotional self-perceptions embedded within personality. TEI comprises four domains: well-being, emotionality, sociability, and self-control. Among these, self-control is particularly relevant to caregiving. It encompasses emotion regulation, frustration tolerance, and the ability to remain composed under pressure are a set of capacities essential for managing the emotional demands of caregiving16. As such, self-control may serve as a mechanism through which resilience contributes to reduced caregiver burden17. Although both resilience and TEI have been independently associated with lower psychological distress, their interactive effects, particularly the potential mediating role of self-control remain under-explored in caregiving populations. Preliminary evidence suggests that individuals with high self-control demonstrate better psychological adaptation in high-stress environments, supporting the plausibility of this mediating model18,19.

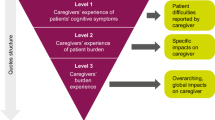

We hypothesized that higher caregiver burden would be associated with lower self-control, which in turn would be associated with lower psychological resilience, yielding a significant indirect effect of burden on resilience through self-control. This corresponds to a simple mediation model (PROCESS Model 4; Ref20.) in which caregiver burden (predictor) influences self-control (mediator), which then influences resilience (outcome), with the direct path from burden to resilience also estimated. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed mediation model, depicting the hypothesized negative association between burden and self-control, the positive association between self-control and resilience, and the potential residual direct path from burden to resilience.

Proposed mediation model (PROCESS Model 4; Ref20.) illustrating the hypothesized indirect effect of caregiver burden on resilience via self-control. The model depicts a negative association between caregiver burden and self-control (Path a), a positive association between self-control and resilience (Path b), and the residual direct path from caregiver burden to resilience (Path c’).

While resilience has sometimes been conceptualized as a personality trait, contemporary frameworks increasingly recognize it as a dynamic and modifiable capacity rather than a fixed disposition21,22. The Brief Resilience Scale8 specifically measures the ability to “bounce back” from stress, aligning more closely with outcome-like adjustment processes than stable personality traits. Accordingly, in this study resilience is treated as a psychological outcome of caregiving stress, shaped by regulatory resources such as self-control.

Conceptual gap

This study addresses a unique conceptual gap by (i) situating caregiving in a collectivist Arab Gulf context, where social expectations may intensify both burden and the cultural value of emotional restraint31,(ii) focusing on self-control as a facet-level construct within trait emotional intelligence, thereby offering more precision than studies treating emotional intelligence globally; and (iii) linking these constructs in a mediation model that clarifies how self-control may operate as the mechanism through which caregiver burden erodes resilience. This facet-level, culturally grounded approach extends existing theory and provides a rationale for targeted interventions.

Proposed hypothesis

We hypothesize that higher caregiver burden is linked to lower self-control, and that this reduction in self-control may make it harder for caregivers to maintain resilience (see Fig. 1). When self-control is included in the model, the direct link between burden and resilience is expected to weaken or even disappear, indicating that self-control may serve as a key pathway connecting the two.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based analytic study at the Behavioral Medicine Department, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) in Muscat, Oman, between March 1, 2024, and March 31, 2025. The study protocol was approved by the SQUH Research and Ethics Committee (Ref. No. BMED 23 043) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki23.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a clear explanation of study aims, anonymity, and the voluntary nature of participation.

Participants

Eligibility criteria were: (i) primary caregiver of a patient diagnosed with a DSM-5 psychiatric disorder for at least 12 months, (ii) age ≥ 18 years, (iii) ability to read Arabic, and (iv) no self-reported cognitive impairment. Caregivers of patients with predominantly neurological or medical illnesses were excluded.

Sample representativeness

Although our sample was drawn from a single tertiary outpatient clinic, its demographic profile closely aligns with findings from another recent study of Omani family caregivers. In that study involving caregivers of patients with acquired brain injury, the sample was predominantly female (53.8%) with a mean age of 38.3 years, mirroring our participant characteristics24. This suggests moderate representativeness, while acknowledging potential differences in caregivers in regional or rural settings.

Sample-size justification

Using nMaster 2.0 for a single-proportion calculation (anticipated moderate-to-high burden = 50%, margin of error = 10%, α = 0.05), the minimum sample was 100. Anticipating 40% incomplete responses, we approached 260 caregivers; 187 provided analysable data, yielding a response rate of 72%.

Data collection process

Data were collected on clinic days via a bilingual paper-and-pencil booklet or an equivalent REDCap™ web form accessed by QR code. Research assistants were trained to clarify items without leading the participant. Missing items were checked in-clinic to minimise data loss. Patient clinical characteristics (diagnosis, medication class, illness duration) were extracted from the electronic medical record with caregiver consent.

Higher scores indicate greater self-control, resilience, and burden, respectively. All scales underwent a standardized forward–backward translation process to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence. The final Arabic versions used in this study were those validated in prior Arabic-speaking populations25,26,27. All instruments were administered in line with the original developers’ guidelines, and no additional permission or licensing was required for non-commercial academic use.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using JASP (Version 0.19.2) and the PROCESS macro (Version 4.2) for SPSS (Hayes, 2009). Normality was inspected via Shapiro–Wilk tests and Q–Q plots; no variable required transformation. Missing values (< 2% per item) were handled using the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm implemented in JASP 0.19.2. The EM procedure iteratively estimated missing values based on maximum likelihood parameters derived from all other available variables in the dataset, thereby preserving the overall variance–covariance structure. This approach was applied separately for each scale (ZBI-12, BRS, TEIQue-SF) before conducting correlational and regression analyses.

-

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables.

-

Bivariate relationships were examined with Pearson’s r and 95% confidence intervals.

-

Multiple linear regression analyses tested independent associations of burden, resilience, and self-control, adjusting for age, gender, and education. Assumptions of homoscedasticity and multicollinearity (VIF < 2 for all predictors) were met.

-

Mediation was tested using PROCESS Model 4 with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples, producing total, direct, and indirect effects with 95% confidence intervals. Effect size was expressed as the completely standardized indirect effect (βcs) (Hayes, 2009).

-

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Out of 260 eligible caregivers approached, 187 completed the survey, yielding a usable response rate of 72%. The mean age of participants was 41.3 ± 12.1 years, and the majority were female (54.5%), married (71.7%), employed (56.1%), and caring for a first‑degree relative (65.2%). Educational attainment varied, with 37.4% reporting a bachelor’s degree. Regarding patient diagnoses, the most commonly reported conditions were ADHD (19.4%), depression (14.7%), and schizoaffective disorder (11.8%). Full sociodemographic and diagnostic distributions are shown in Table 1.

The overall mean caregiver burden score (ZBI‑12) was 21.7 ± 8.9, reflecting a moderate level of perceived burden. Self‑control, measured via the TEIQue‑SF subscale, averaged 37.6 ± 6.6, and resilience (BRS) scores averaged 3.24 ± 0.71, indicative of normative resilience. Caregivers reported moderate perceived burden (ZBI-12: M = 21.7, SD = 8.9, α = 0.80), average levels of self-control (TEIQue-SF: M = 37.6, SD = 6.6, α = 0.80), and normative resilience (BRS: M = 3.24, SD = 0.71, α = 0.50). Internal consistency was acceptable for ZBI-12 and TEIQue-SF, though lower for the BRS, consistent with prior Arabic validations25.

Correlations

Pearson’s correlations, Table 2, revealed that caregiver burden was significantly and negatively associated with both self-control (r = − 0.28, p < 0.001) and resilience (r = − 0.24, p = 0.001). Self-control was positively associated with resilience (r = 0.49, p < 0.001). Multicollinearity was not observed (all VIFs < 1.4) (O’Brien, 2007).

Regression analyses

In adjusted linear regression models controlling for sociodemographic variables, self-control remained a strong independent predictor of resilience (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). The direct association between caregiver burden and resilience was no longer significant (β = −0.05, p = 0.29), suggesting a potential mediation pathway. The overall model was statistically significant (R2 = 0.31, F(5,181) = 16.4, p < 0.001). Independent-samples t-tests indicated no significant gender differences in caregiver burden, self-control, or resilience (all p > 0.10). Gender was also tested as a covariate in regression models and was non-significant.

p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***.

To further examine the independent associations among the study variables, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses predicting resilience while controlling for sociodemographic covariates (age, gender, and education). As expected, self-control remained a strong independent predictor of resilience (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). The direct effect of caregiver burden on resilience was not significant after accounting for self-control (β = 0.05, p = 0.29), consistent with the hypothesized mediation pathway. The overall model was statistically significant (R2 = 0.31, F(5,181) = 16.4, p < 0.001). Full regression results are presented in Table 3.

Mediation analysis

A mediation analysis, using PROCESS Model 4 with 5,000 bootstrap samples, tested whether self-control mediated the relationship between caregiver burden and resilience, following the guidelines of Hayes. As illustrated in Fig. 2, higher caregiver burden was associated with lower self-control (Path a: β = −0.28, SE = 0.09, p = 0.002), which in turn was significantly linked to greater resilience (Path b: β = 0.52, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of caregiver burden on resilience through self-control was statistically significant (β = −0.15, 95% CI: −0.24 to −0.07), while the direct effect of burden on resilience became non-significant (Path.

c: β = −0.06, SE = 0.05, p = 0.21), indicating full mediation. These findings underscore self-control as a central psychological mechanism by which caregiver burden impacts resilience.

Discussion

This study examined the role of self-control in the relationship between subjective caregiver burden and psychological resilience among caregivers of psychiatric patients in Oman. Drawing on the stress process model28 and trait emotional intelligence theory (Petrides, 2009), the study hypothesised that caregiver burden would undermine resilience indirectly through the erosion of emotion regulation skills. This approach addresses calls for more specific models of stress adaptation rather than treating burden and resilience as directly linked29,30. The findings identify a modifiable pathway in which higher caregiver burden is associated with lower self-control, which in turn relates to lower resilience—a pattern that may be especially relevant in collectivist cultural contexts31. The direct path from burden to resilience became non-significant when accounting for self-control, supporting full mediation. These results align with previous studies that identified emotion regulation skills as critical buffers in caregiving stress contexts32,33, although prior research often treated emotional intelligence globally rather than isolating subcomponents34. The current focus on self-control adds precision by suggesting that inhibitory regulation may be particularly important in environments where emotional restraint is culturally emphasised, as in Oman.

Comparisons with prior literature from other countries highlight both similarities and differences. While partial mediation between caregiver burden and resilience via self-control or related constructs is frequently observed in Western contexts such as the United States and Europe35, the full mediation observed here mirrors findings from studies in high emotional-restraint cultures such as Japan and South Korea, where inhibitory control is strongly reinforced in socialisation practices. Moreover, research from lung cancer caregiving in Greece in a recently published meta-synthesis in the field has similarly documented that caregivers frequently endure high emotional strain, role changes, and unmet informational needs13. Such cross-cultural parallels suggest that, despite differences in illness context, emotion-regulatory capacities consistently influence resilience outcomes. However, differences also emerge,in Western samples, gender and trait emotional intelligence often interact to shape caregiver well-being14, whereas the current study did not test gender moderation. These international comparisons suggest that while the mediating role of self-control may be universal, its strength and the role of other moderators could vary by cultural norms and gender roles. Although prior literature has suggested gender differences in caregiver outcomes14, our exploratory analyses found no significant differences. This may reflect the collectivist caregiving context in Oman, where caregiving responsibilities are broadly shared across genders.

The moderate burden levels observed (mean ZBI-12 = 21.7) are consistent with a Saudi Arabian sample36, suggesting that while stress exposure is regionally typical, the processing of stress may vary with emotion-regulatory skills. In addition, findings from Iran and East Asia37,38 have shown that resilience interventions may require different emphasis in collectivist versus individualist societies, underscoring the value of culturally sensitive theoretical frameworks.

Beyond empirical comparisons, the results make several theoretical contributions. First, within the stress process model, they highlight the importance of internal mediators such as self-control rather than assuming a direct link from stress exposure to outcome28. Second, in trait emotional intelligence theory, they support a facet-level view, showing that specific skills like self-control are key drivers of adaptation (Petrides, 2009), challenging models that aggregate emotional intelligence. Third, in resilience theory, they encourage a shift from viewing resilience as fixed to seeing it as a modifiable capacity shaped by regulatory abilities21. Recognising resilience as partly built on emotion regulation opens possibilities for targeted interventions, particularly in cultures that value emotional discipline22,39.

These theoretical advances have practical implications. Interventions should target both external burden and the self-regulatory skills that mediate stress responses40. Mindfulness-based and acceptance-based emotion regulation training have shown promise for improving self-control41, and culturally adapted versions could benefit Omani caregivers by enhancing individual wellbeing and family functioning. Future intervention trials could also test gender-specific adaptations and incorporate trait emotional intelligence training, given evidence from other countries that these factors interact to influence resilience. In addition to resilience, other positive psychological constructs may also be relevant for understanding caregiver adaptation. Beyond resilience, the concept of post-traumatic growth (PTG) offers an additional framework for understanding the emotional transformations of caregivers42. While resilience reflects the capacity to “bounce back,” PTG refers to positive psychological change and personal growth that can emerge following adversity43. Caregivers who successfully reappraise and find meaning in their role may experience enhanced well-being, stronger relationships, or spiritual growth. Although PTG was not assessed in this study, future research in Omani caregivers should explore how burden may, for some, catalyze growth as well as strain.

Limitations

This study has several limitations which must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes any claims about causal relationships. Also, the internal consistency of the Brief Resilience Scale was modest (α = 0.50) and may have affected the strength of observed relationships. Furthermore, the use of self-report measures introduces potential common-method variance, although Harman’s single-factor test suggested that this was not a major concern44. Moreover, important variables such as length of caregiving experience, clinical indicators of the patient’s illness severity (e.g., psychiatric symptom scales), and the presence and quality of informal support networks were not assessed, potentially influencing both self-control and resilience scores. Finally, the findings may have limited generalizability, as the study was conducted in a single tertiary clinical site, which may not fully represent other healthcare settings. Recognising these limitations leads naturally to considerations for future research.

Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to test the stability and directionality of the mediation pathway over time. Running randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to examine whether structured self-control training programmes (e.g., mindfulness-based self-regulation, cognitive control exercises) lead to measurable improvements in resilience among caregivers would provide stronger evidence for the proposed mechanisms. Future research should also integrate mixed-methods approaches that combine quantitative modelling with qualitative interviews to capture the nuanced, culturally embedded experiences of Omani caregivers. Subgroup analyses by gender, relationship to the patient, or dominant religious coping strategies would further illuminate how the mediation pathway might vary within Omani society and in other cultural contexts. These research directions would help refine both culturally grounded theoretical models and tailored intervention programmes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study may advance our understanding by specifying self-control as a key mediating mechanism linking caregiver burden to psychological resilience among psychiatric caregivers in Oman. It extends theoretical models by emphasising the importance of internal regulatory skills and offers practical guidance for developing culturally sensitive intervention strategies aimed at strengthening caregiver adaptation to chronic stress.

Data availability

The research data are available based on a request sent to the corresponding author: m.alalawi2@squ.edu.om.

References

Awad, A. G. & Voruganti, L. N. P. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: A review. Pharmacoeconomics 26(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005 (2008).

Chan, S.W.-C., Wong, D. F. K. & Yeung, S. M. Coping with caregiving stress among Chinese caregivers of persons with schizophrenia: The role of positive emotions and coping. Community Ment. Health J. 53(7), 747–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0095-7 (2017).

Al-Adawi, S., Dorvlo, A. S. S. & Burke, D. T. Caregiver burden among relatives of mentally ill patients in Oman. Br. J. Psychiatry 181, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.2.125 (2002).

Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E. & Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 20(6), 649–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/20.6.649 (1980).

Schulz, R. & Sherwood, P. R. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 108(9 Suppl), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c (2008).

Yu, D. S. F., Cheng, S. T. & Wang, J. Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 79, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.008 (2018).

Cooper, A. & Petrides, K. V. A psychometric analysis of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue–SF) using item response theory. J. Pers. Assess. 92(5), 449–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.497426 (2010).

Smith, B. W. et al. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972 (2008).

Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 21(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259810000420 (2011).

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C. & Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 5(1), 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338 (2014).

Gaugler, J. E., Kane, R. L., Kane, R. A. & Newcomer, R. Resilience and transitions from dementia caregiving. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 62(1), P38–P44. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.1.p38 (2007).

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R. & Kokkinaki, F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br. J. Psychol. 98(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X120618 (2007).

Tragantzopoulou, P. & Giannouli, V. Echoes of support: A qualitative meta-synthesis of caregiver narratives in lung cancer care. Healthcare 12(8), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12080828 (2024).

Zhong, Y., Li, Z. & Relojo-Howell, D. The role of emotional intelligence and gender in the association between maternal attachment and anxiety in youth: A moderated mediation model. ISPEC Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 1(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15426467 (2025).

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P. & Caruso, D. R. Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits?. Am. Psychol. 63(6), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503 (2008).

Zeidner, M., Matthews, G. & Roberts, R. D. The emotional intelligence, health, and well-being nexus: What have we learned and what have we missed?. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 4(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01062.x (2012).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781 (2015).

Duckworth, A. L. & Gross, J. J. Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23(5), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414541462 (2014).

Tugade, M. M. & Fredrickson, B. L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86(2), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320 (2004).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach 2nd edn. (Guilford Press, 2018).

Denckla, C. A. et al. Psychological resilience: an update on definitions, a critical appraisal, and research recommendations. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11(1), 1822064. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1822064 (2020).

Troy, A. S. & Mauss, I. B. Resilience in the face of stress: Emotion regulation as a protective factor. In Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan (eds Southwick, S. et al.) 30–44 (Cambridge University Press, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511994791.004.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Roslin, H. et al. Caregiving preparedness and caregiver burden in Omani family caregivers for patients with acquired brain injury. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 23(4), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.6.2023.040 (2023).

Al-Dassean, K. A. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF). Cogent Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2023.2171184 (2023).

Bachner, Y. G. Preliminary assessment of the psychometric properties of the abridged Arabic version of the Zarit Burden Interview among caregivers of cancer patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 17(5), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2013.06.005 (2013).

Baattaiah, B. A., Alharbi, M. D., Khan, F. & Aldhahi, M. I. Translation and population-based validation of the Arabic version of the brief resilience scale. Ann. Med. 55(1), 2230887. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2230887 (2023).

Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J. & Skaff, M. M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583 (1990).

Prisacaru, A. The Role of Psychological Resilience, Coping Mechanisms and Locus of Control in Managing Students’ Perceived Stress during Exams. International Journal For. Multidiscip. Res. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i06.29941 (2024).

Karasievych, S. A., & Karasievych, M. P. Psychological health and self-control of the individual. Bulletin of Luhansk Taras Shevchenko National University. Pedagogical Sciences, 4(363), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.2958/2227-2844-2024-4(363)-47-52. (2024).

Ibrahim, A.-S. Cultural perspectives on mental health practice in Arab countries. Arabpsynet. http://arabpsynet.com/Archives/OP/OP.j12abdelsattar.pdf (2001).

Lin, L.-L. & Lin, C.-C. Roll with the punches: Applying resilience to caregiver’s burden. J. Nursing (China) 66(3), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.6224/JN.201906_66(3).12 (2019).

Panzeri, A. et al. Emotional Regulation, Coping, and Resilience in Informal Caregivers: A Network Analysis Approach. Behav. Sci. 14(8), 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080709 (2024).

Rastogi, N. & Kumari, C. The Way You Feel Can Either Get in The Way or Get You on The Way: A Systematic Review of Emotional Intelligence. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.32628/ijsrst52411293 (2024).

Kwok, J. Y. Y. et al. Multiphase optimization of a multicomponent intervention for informal dementia caregivers: Study protocol. Trials 24(1), 791. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-023-07801-3 (2023).

Al-Shammari, S. A. et al. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 24(3), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.4103/JFCM.JFCM_117_16 (2017).

Farahani, M.-N. & Khanipour, H. The influence of culture on the experience of affects, stress, personality traits, and mental health: Findings from cross-cultural studies. Res. Psychol. Health 12(3), 1–23 (2018).

Kang, G. Cultural influences on regulating emotion. Intuition 13(2), 8 (2018).

Hu, Y. Examining the effects of teacher self-compassion, emotion regulation, and emotional labor strategies as predictors of teacher resilience in EFL context. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1190837 (2023).

Zarit, S. H. & Savla, J. Caregivers and stress. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine (eds Gellman, M. D. & Turner, J. R.) 339–344 (Academic Press, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800951-2.00042-X.

Smith, T. R., Panfil, K., Bailey, C. & Kirkpatrick, K. Cognitive and behavioral training interventions to promote self-control. J. Exp. Psychol.: Animal Learn. Cognit. 45(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/xan0000208 (2019).

Villena, A., Morales-Asencio, J. M., Quemada, C. & Hurtado, M. M. Sustaining the burden: A qualitative study on the emotional impact and social functioning of family caregivers of patients with psychosis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 51, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2024.05.015 (2024).

Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 (2004).

Kamakura, W. A. Common methods bias. Wiley Int. Encycl. Marketing https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem02033 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR, MAA, AG, and AA contributed to the study design. AR, MAA, and AG collected the data. AA and MAlA conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript. MAA and MAlA critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

The publisher has all authors’ permission to publish research findings in an online open access publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Marshoudi, A.R., Al Aisaiee, M., Al Ghafri, A.Z. et al. Self-control as a mediator between caregiver burden and psychological resilience among psychiatric caregivers in Oman. Sci Rep 15, 35219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19723-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19723-y