Abstract

Attentional focus plays a crucial role in motor performance; however, its impact on young adolescent females across varying task difficulties remains unclear. This study aims to answer the following question: how do attentional focus strategies affect motor performance in young adolescents, and does task difficulty modify this effect? A sample of 112 healthy girls aged 10–12 years (M = 10.98, SD = 0.82) was randomly assigned to one of four conditions: external focus (focus on the part of the ball contacted during the kick), holistic focus (focus on feeling solid contact during the kick), internal focus (focus on the part of the foot making contact during the kick), or control (no focus instruction). Participants completed 40 soccer kicking trials under two levels of task difficulty: kicking a stationary ball and kicking a moving ball. Findings revealed that under low task difficulty, performance was significantly better with an external focus compared to an internal focus (p = .001), and no instruction (p = .004). Similarly, a holistic focus led to significantly better performance than an internal focus (p = .0001) and no instruction (p = .0001). However, under higher task difficulty, only the holistic focus group sustained superior performance, outperforming all other groups (p ≤ .05). These results highlight the moderating role of task difficulty in attentional focus research and suggest the potential advantages of holistic focus in complex motor tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A core aim of motor behavior research is to examine how individual, task-related, and environmental variables influence and optimize motor performance. This endeavor has sparked the development of various specialized research areas, each concentrating on particular elements of the performer’s experience during training (for review, see1,2). The adoption of focus of attention strategies—deciding where to direct one’s attention to enhance motor performance—represent one of the most fascinating and widely explored topics in the field, drawing interest from researchers globally (for review, see3,4,5). For example, when throwing or kicking a ball, should attention be focused on the motion of the hand or leg, or instead on an external target such as a bullseye or the corner of a goal? Internal focus of attention refers to concentrating on one’s own body movements—such as the motion of the limbs during the action3. In contrast, external focus of attention involves directing attention toward the intended outcome of the movement in the environment, like hitting a target or reaching a specific location3. This dilemma applies broadly across different tasks and activities; all centered on the critical question of where our attentional focus should be directed to maintain or achieve optimal performance during the execution of a motor task? For more than twenty years, researchers have examined whether an external or internal focus of attention is more effective in different situations. Several studies have demonstrated that focusing attention externally, on the intended movement effect, leads to better motor performance than concentrating internally on the movement itself (for review, see3,4,5). As an example, Lohse et al.6 found that focusing attention externally rather than internally improved dart-throwing performance, as shown by lower absolute error, reduced triceps brachii EMG activity, and shorter preparation time between throws. The benefits of adopting an external focus of attention have been demonstrated across various motor tasks, including standing long jumps (for a review, see7), balance tasks (for a review, see8), as well as throwing (e.g.,9,10), and kicking skills11. Importantly, these advantages extend to individuals with disabilities, such as children with intellectual disabilities12, those with hearing impairments13, and people with visual impairments14,15. However, the effectiveness of external focus was not consistently supported across all relevant studies. For example, in a study involving skilled golfers, the no-focus instruction (control) resulted in better putting performance compared to both external and internal focus conditions16. EEG data further revealed that, during the no-focus condition, attentional patterns initially resembled those seen with external focus but shifted toward internal focus just before putting16.

Why does an external focus of attention enhance motor performance? Three primary explanations have been suggested to account for the performance improvements linked to an external focus. The first, known as the constrained action hypothesis17,18, argues that an internal focus leads to conscious control, which restricts the motor system by interfering with automatic control mechanisms. In contrast, an external focus encourages a more automatic control process, relying on unconscious, rapid, and reflexive actions. Notably, these claims have been supported by evidence19,20,21,22. The second and third explanations, derived from the OPTIMAL theory, propose that (2) an external focus of attention directs attention to the task goal, strengthening the link between goal and action, and (3) success in movement due to an external focus boosts expectations for future success, potentially resulting in more effective performance23. Previous research has also supported these explanations22,24,25, for example, by showing that adopting an external focus of attention enhances motivational state22,24. It is important to emphasize that these cognitive and motivational effects were not directly measured in the current study. Moreover, it remains unclear whether an external focus primarily influences motivational factors before affecting cognitive and affective components. However, based on the notion that successful movement outcomes resulting from an external focus enhance expectations for future success—thereby potentially improving performance—it is reasonable to infer that motivational effects likely follow the initial success rather than precede it. Studies have also shown that an external focus improves movement efficiency, as reflected in reduced oxygen consumption26, lower muscular activity27,28, and a decrease in heart rate29.

A recent strategy involving attentional focus has been suggested to be as effective as an external focus of attention30. Holistic focus of attention involves concentrating on the general sensations or feelings experienced while performing a motor task, such as feeling explosive or smooth30. However, studies have shown the benefits of holistic focus in activities like the standing long jump30,31, badminton short serve32, and badminton long serve33. It is argued that this approach allows individuals to focus on the internal sensations of movement (e.g., feeling explosive), potentially providing similar advantages as an external focus of attention30,32. However, this type of focus has not always been effective, with no significant effects reported in tasks such as balance34 swimming35, and soccer shooting36. One potential explanation involves the nature of the task itself. Holistic focus appears to be more beneficial in explosive or rhythm-based tasks (e.g., jumping, badminton short serve) that rely on fluid coordination and global movement patterns. In such contexts, focusing on a general feeling (e.g., being “explosive” or “smooth”) may enhance motor efficiency by reducing conscious control and promoting automaticity30,32. Conversely, tasks that require fine motor control, precise spatial accuracy, or continuous balance regulation—such as balance tasks, swimming, or soccer shooting—may not benefit similarly. In these tasks, a holistic focus may be too abstract or diffuse, failing to provide the task-specific cues needed to optimize performance. Thus, further research is needed to fully understand the impact of holistic focus on motor performance.

Despite promising efforts in the field of attentional focus, contradictory findings emerge regarding various factors (e.g., age, expertise level, task nature). For instance, studies involving children have yielded mixed results. Some research indicates that an external focus of attention enhances performance (e.g.,37,38,39), while other studies suggest an advantage of an internal focus (e.g.,40,41,42). Additionally, some studies have found that both internal and external focus equally affect motor performance (e.g.,43,44,45). More recently, Abedanzadeh et al.36 found that external focus benefited the acquisition stage, but not retention or transfer tests. This highlights the importance of conducting more in-depth studies with children to better understand the nuances of attentional focus across different contexts. The literature also presents divergent findings regarding the influence of attentional focus across tasks of differing complexity. For instance, Wulf et al.46 observed that while attentional focus did not significantly affect performance in a simple balance task, an external focus led to improved outcomes in a more complex version of the task. Conversely, Raisbeck et al.47 demonstrated that external focus instructions enhanced performance irrespective of task difficulty (i.e., higher Index of Difficulty based on target size and distance). Complementing this, Yamada et al.48 proposed that the mediating factor in attentional focus effects is the level of practice (i.e., early versus advanced stages of practice) rather than the complexity of the task, specifically in speed-accuracy trade-off tasks. It is important to note that both studies were conducted within the context of speed-accuracy paradigms (Reisbeck et al., 2020; Yamada et al., 2020), highlighting the necessity for further research in sport-specific contexts to determine the generalizability of these findings.

The present study pursued two primary objectives. First, it aimed to examine the impact of three attentional focus strategies—holistic, external, and internal—on motor performance in children. This investigation was prompted by previous research showing inconsistent findings in this area among children (e.g.,38,40,41,42,44), highlighting the need for further studies to clarify the effects of attentional focus in young populations. Additionally, the current literature has paid limited attention to the influence of holistic focus in children32,33,35, making this a valuable area for exploration. Third, the study explored the role of task difficulty as a potential moderating factor in the relationship between attentional focus and motor performance. Indeed, previous research has shown that engaging in relatively challenging tasks can change the activity patterns of brain regions49,50. We examined whether task difficulty influences the effectiveness of different attentional focus strategies, given that some studies have suggested external focus benefits performance in challenging tasks46, while others have found no such moderating effect47,48. Based on these considerations, it was hypothesized that attentional focus strategies would differentially affect motor performance in young adolescents, with external and holistic focus expected to enhance performance more than internal focus and control condition, particularly under conditions of increased task difficulty.

Method

Participants

A total of 112 healthy female participants, ranging in age from 10 to 12 years (M = 10.98 years, SD = 0.82), were recruited to take part in the current study. Their mean height was 139.1 cm (SD = 2.24), and mean weight was 30.32 kg (SD = 2.34). All participants were selected based on predefined inclusion criteria, which required them to be free of any known neurological, developmental, or physical conditions that could interfere with their performance in the task. Moreover, none of the participants had any previous exposure to the specific aims or hypotheses of the study, ensuring that their responses were not biased by prior knowledge. It was also confirmed that none of the girls were involved in any organized or regular soccer training programs, which helped control for prior experience in the motor skill tasks assessed.

A sensitivity power analysis was performed using G*Power51 to determine the minimum effect size detectable given the sample size, alpha level, and desired statistical power. A sensitivity power analysis assuming an α of .05 and power of .80, indicated that our sample size would allow to detect moderate effect of f = .27, which is in line with the effect sizes obtained in previous studies investigating the effect of attentional focus on motor performance4,52,53. The study was approved by the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz’s ethics committee (approval code: scu.ec.ss.404.1111). Informed consent forms were acquired from the parents/guardians, and verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Task

Accuracy performance

Participants were instructed to perform inside-foot kicks at designated target zones positioned on a wall and extending to the ground (see Fig. 1 for a visual representation of the setup). The objective was to strike the soccer ball so that it hit the target area yielding the highest possible score. Hitting zone 3 awarded three points, while zones 2 and 1 awarded two and one point(s), respectively. No points were given for missing the target. Other researchers have used a similar or identical apparatus and task54,55,56.

Set-up of experimental task (Derived from22).

In the easy condition, participants were instructed to kick a stationary ball positioned 6 m from the target. In the more challenging condition, they were required to kick a rolling ball. To ensure consistent ball velocity, direction, and position across trials, the ball was released from a small ramp (40 cm high, 70 cm long) set at a 45° angle and placed 2.7 m from the designated kick-off point. The total distance from the target to the kick-off point remained 6 m. Participants began 2 m behind the kick-off spot and were instructed to approach and kick the ball as it rolled over that point. This dynamic version of the task posed a greater challenge, particularly for novice participants, as it introduced added demands for timing, coordination, and agility when interacting with a moving ball.

Adherence to attentional focus cues

At the conclusion of each stage (i.e., right after completing both the easy and difficult tasks), participants were asked to rate how consistently they followed attentional focus cues on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time).

Procedure

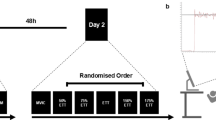

After completing a 10-min warm-up, participants individually met with a female experimenter who provided basic guidance on executing an accurate inside kick. Each participant observed a demonstration of the inside kick technique. Subsequently, participants were randomly allocated to one of four groups: external focus (EF), holistic focus (HF), internal focus (IF), or control. Participants were not informed of their own or their peers’ group assignments to help maintain blinding. Additionally, the experimenter was not involved in the group assignment process to prevent any potential bias. Prior to introducing the experimental conditions, all participants performed five individual pretest trials (see Fig. 2 for research design). Following the pretest, those in the experimental groups were informed that they would practice the task with attention directed toward a specific instructional focus.

Each participant completed a total of 40 trials involving a soccer task with two levels of difficulty: one relatively easier level (i.e., kicking a stationary ball) and one more challenging (i.e., kicking a rolling ball). They performed 20 trials for each type of kick. The sequence of conducting trials under the different conditions (low and high difficulty) was counterbalanced: half of the participants in each group began with the lower difficulty level of the task, followed by the higher difficulty level, while the other half started with the higher difficulty level and then completed the lower difficulty one. Before performing the task, participants were given verbal instructions regarding their attentional focus. The external focus group was told to “focus on the part of the ball contacted during the kick.” External focus of attention can be categorized as distal (e.g., focusing on a target like a bullseye) or proximal (e.g., focusing on the ball being struck), based on the distance from the performer. While distal focus often benefits skilled performers (e.g.,57,58,59,60), proximal focus may be more suitable for novices57,61,62,63. Given our participants’ novice status, we adopted a proximal external focus strategy. The holistic focus group was told to “focus on feeling solid contact during the kick.” The internal focus group was told to “focus on the part of the foot making contact during the kick.” The control group was given no focus cue to use during both tasks. Participants received focus instructions before the first trial and were reminded of them after every five trials. These instructions were similar to those used in previous studies30,36. After every 20 trials, the participants were asked to report their adherence to attentional focus cues. Throughout the experiment, participants could see where the ball hit the target, but no additional feedback was provided.

Data analysis

To ensure homogeneity of groups at the beginning of the study, pretest inside-foot kicks accuracy scores between the four groups were assessed via an independent one-way ANOVA. Next, for comparing four groups in 2 levels of difficulty, a Group (4) × Difficulty level (2) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on inside-foot kicks accuracy data during performance. Significant main effects and interactions were followed-up with Univariate ANOVAs and Sidak post-hoc tests to determine which groups and/or time points contributed to significant effects. Effect sizes were indicated with the partial eta squared (ηp2), with .01 ≤ ηp2 ≤ .059 indicating small, .06 ≤ ηp2 ≤ .139 indicating medium, and ηp2 ≥ .14 indicating large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). The level of significance was set at p ≤ .05, and all statistics were processed using SPSS 17.0.

Results

Pretest

Table 1 displays group means and standard deviations in all phases of the experiment. Results of the univariate ANOVA indicated no group differences in serve accuracy at the pretest indicating random assignment was successful in establishing homogenous groups, F(3,108) = .72, p = .54, ηp2 = .02.

Performance

Mean accuracy scores throughout all phases are presented visually in Fig. 3. All participants improved across the 40 trials of practice. This is supported by a significant effect of difficulty level, F(2,216) = 29.99, p = .0001, ηp2 = .22. Across practice, significant group differences were present, F(3,108) = 7.73, p = .0001, ηp2 = .18. Also, a significant interaction between difficulty level and group was indicated F(6,216) = 3.80, p = .001, ηp2 = .1. For more investigation of significant interaction we conduct two univariate ANOVAs separately for easy level and challenging level (difficulty levels). A significant effect of easy level, F(3,108) = 13.57, p = .0001, ηp2 = .27 and significant effect of challenging level, F(3,108) = 7.43, p = .0001, ηp2 = .17 were present.

Sidac post-hoc tests results for easy level indicated significant differences between external focus and control (∆mean = .19, SE = .05, p = .004, Cohen’s d = 1.01), holistic focus and control (∆mean = .26, SE = .05, p = .0001, Cohen’s d = 1.07), external focus and internal focus (∆mean = .22, SE = .05, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 1.41), and holistic focus and internal focus (∆mean = .29, SE = .05, p = .0001, Cohen’s d = 1.32).

Sidac post-hoc tests results for challenging level indicated significant differences between holistic focus and external focus (∆mean = .16, SE = .05, p = .017, Cohen’s d = .72), holistic focus and control (∆mean = .16, SE = .05, p = .015, Cohen’s d = .73), and holistic focus and internal focus (∆mean = .24, SE = .05, p = .0001, Cohen’s d = 1.10).

Also, we conducted three paired-sample T-tests for investigating of differences between two levels of difficulty (Easy vs. Challenging) in each of attentional groups. The results of these tests showed there are significant differences between difficulty level in internal focus (t(27) = 5.51, p = .0001, Cohen’s d = 0.87 in favor of easy level), in external focus (t(27) = 6.62, p = .0001, Cohen’s d = 1.69 in favor of easy level) and in holistic focus (t(27) = 3.32, p = .003, Cohen’s d = .78 in favor of easy level).

Adherence to attentional instructions

Self-reported adherence to attentional instructions was relatively high among all groups. Scores at easy level performance for an internal focus (M = 4.53, SD = .51), external focus (M = 4.71, SD = .46) and holistic focus (M = 4.46, SD = .47) did not differ from each other, χ2(2) = 2.68, p = .44. Also scores at challenging level performance for an internal focus (M = 4.76, SD = .46), external focus (M = 4.68, SD = .48) and holistic focus (M = 4.64, SD = .49) did not differ from each other, χ2(2) = .32, p = .85.

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate how three types of attentional focus (i.e., holistic, external, and internal) affect motor performance in young adolescents. Additionally, it examined whether task difficulty moderates this relationship, specifically exploring if the effectiveness of each attentional focus strategy varies depending on how challenging the task is. Overall, the findings indicated that all groups performed better on the simpler soccer shooting task compared to the more challenging version. The results also revealed that when the task required kicking a stationary ball, girls who adopted holistic and external focus of attention strategies significantly outperformed their peers in both the control and internal focus groups. Interestingly, as the task increased in difficulty—shifting to kicking a rolling ball—only the holistic focus group continued to excel, surpassing not only the internal focus and control groups but also the external focus group. These results suggest that a holistic attentional strategy may offer consistent performance advantages, even under more demanding task conditions.

During the relatively less challenging task (i.e., kicking a stationary ball), participants in the holistic and external focus of attention groups demonstrated superior performance compared to those in the internal focus and control groups. Notably, the performance of the holistic and external focus groups did not differ significantly. These results imply that under less challenging conditions, adopting holistic and external focus of attention strategies may provide a performance advantage over an internal focus or no guidance (control condition). Similar benefits of employing holistic and external focus of attention strategies have been reported in prior research, particularly in motor tasks like the standing long jump30. In their study, Becker et al.30 found that participants who received external or holistic focus instructions achieved significantly greater jump distances compared to those given internal focus cues or no specific instructions. These findings highlight the potential of attentional focus strategies to enhance motor performance by directing attention away from bodily movements and toward the intended movement effect (i.e., external focus) or the general feeling or sensation associated with performing the task (holistic focus).

In contrast to our findings, a previous study using a similar task (i.e., kicking a stationary soccer ball) did not report comparable benefits for either external or holistic attentional focus36. In fact, that study found no significant differences between external, holistic, and internal focus instructions during both the practice and retention phases. One possible explanation lies in the interaction between the nature of the task (i.e., soccer) and the participants’ gender. While Abedanzadeh et al.36 included male participants, our study involved female participants. Soccer is traditionally viewed as a male-dominated sport, with boys often perceived as more capable and expected to perform better64. These societal expectations may provide boys with a psychological advantage, allowing them to approach the task with greater confidence and fewer doubts65. This mindset may diminish the observable impact of attentional focus strategies, particularly during the early stages of performing a less challenging task. This interpretation aligns with Abedanzadeh et al.’s36 findings, where no significant differences were observed among the three attentional focus groups during both practice and retention phases. Although we did not conduct a retention test, the overall pattern in Abedanzadeh et al.’s36 study supports the potential interaction between task type and participant gender, especially during initial stages of performance. In our study, female participants—who lack the same societal advantage or gender stereotype activation in soccer tasks (e.g.,54,66)—displayed clearer effects of attentional focus. Specifically, both external and holistic focus strategies enhanced soccer performance. These findings contributes to the literature by offering a relatively clear picture of how three types of attentional focus influence soccer performance in a less challenging task.

The present study also demonstrated that as the task increased in difficulty—shifting to kicking a rolling ball—only the holistic focus group continued to excel, surpassing not only the internal focus and control groups but also the external focus group. These finding highlights that adopting a holistic focus of attention could be effective even in relatively challenging tasks. Moreover, it could be inferred that as the task increased in difficulty, the effectiveness of external focus of attention decreased. These findings contribute to our understanding of how attentional focus strategies affect soccer performance among female novices. One possible explanation is that in more demanding tasks, an external focus of attention may not aid performance because novices lack the motor proficiency needed to execute movements effectively. Generally, as training progresses, performers acquire the necessary knowledge, and parts of the performance become automatic1,2. Adopting an external focus of attention may help novices experience some of this automaticity earlier in relatively simple tasks17,18,23. However, these benefits may diminish when novices face more challenging tasks. This could be because difficult tasks impose greater cognitive and motor demands, requiring novices to rely more on the overall feel or sensation of the movement, rather than on specific internal (e.g., limb movement) or external (e.g., the ball) cues. In essence, for novices performing challenging tasks, directing attention toward general kinesthetic sensations may enhance performance. Apparently, overly specific internal or external focus instructions might interfere with the natural coordination and motor control needed for successful execution in relatively challenging tasks.

Recent research distinguishes internal focus into three subtypes: traditional internal focus (body-movement-oriented), bodily-sensation-oriented focus, and movement-adjustment-oriented focus, each affecting motor performance differently (e.g.,3,5,67,68). Traditional internal focus, which directs attention to specific body movements, often disrupts automatic motor control and impairs performance3,5. In contrast, focusing on bodily sensations or making movement adjustments tends not to impair—and may even improve—performance by enhancing somatic awareness or technique correction67,68. Our study’s internal focus instructions emphasized body-movement orientation, which likely explains the negative effects observed. Two additional points should be noted. First, positive effects of internal focus are often reported in endurance sports67,68, suggesting that task demands influence its effectiveness. Second, bodily-sensation internal focus overlaps with the holistic focus of attention, which involves concentrating on general bodily sensations. This indicates that some benefits attributed to bodily-sensation internal focus may actually reflect mechanisms similar to holistic focus. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms and effectiveness of these distinct internal focus types across different tasks.

Conclusion and practice application

In our study designed to explore the effect of attentional focus on the motor performance of young girls in a task with different levels of difficulty, we observed advantages for both external and holistic focus in performing the less challenging task. In contrast, only a holistic focus of attention proved beneficial in the more challenging version of the task. The present study’s findings have practical implications especially for girls developing soccer skills, as they highlight the impact of different attentional cues on motor skill learning. Coaches and sports educators should be mindful of these nuances when designing training interventions, as a one-size-fits-all approach may not be optimal for all performers. In light of these findings, there is a strong need for more individualized approaches in sports training that consider factors such as age, skill level, and task complexity. Each athlete’s unique characteristics—including experience, cognitive style, and sociocultural background—may influence how they respond to different coaching strategies and attentional focus instructions. Specifically, these results suggest that different attentional focus strategies may be more effective depending on the difficulty of the task at hand, which can guide coaches and trainers in training programs to match the skill level and developmental stage of their athletes. For example, during practice sessions with less challenging tasks, both external and holistic focus techniques could be employed to optimize performance. However, as the tasks become more complex, focusing on holistic feeling or sensation associated with performing the skill rather than external cues might be more beneficial for skill acquisition and performance among novices. Overall, we believe that the effects of attentional focus strategies should not be oversimplified. A clear understanding of their effectiveness requires consideration of factors such as the nature and difficulty of the task, the level of expertise, and even interaction between the nature of the task (e.g., soccer) and the participants’ gender. For instance, recent studies have suggested that an external focus strategy benefits experienced children but not novices35. Although this challenges previous research that supported the effectiveness of external focus for novices (e.g.,37,38,39), it is significant because it offers new insights that can help refine conclusions.

Limitations and future research directions

Nonetheless, this study is not without its limitations. One key limitation is the lack of assessment of potential variables that could have contributed to a more conclusive understanding of attentional focus effects (e.g., conscious motor processing, task difficulty). Furthermore, the study involved only female participants, which limits the generalizability of the results. Notably, the motor task we used was based on a soccer skill. Soccer is culturally gender-typed as a male-dominated sport, and girls may receive less social support and encouragement in this area64. These cultural factors may have influenced participants’ performance and contributed to the observed data patterns, particularly given that culture has been shown to modulate the effects of various independent variables in motor learning69. Including male participants in future studies could allow for meaningful comparisons with similar studies36 and help determine whether gender influences the interaction between task type (e.g., soccer) and attentional focus. Future research should incorporate objective measures (e.g., automaticity, conscious motor processing, brain-based analysis) to more accurately capture underlying mechanisms and yield stronger, quantifiable insights into task performance. Moreover, our sample consisted solely of novices with limited experience in soccer. Therefore, the results can only be generalized to similar inexperienced populations. Future studies should explore whether these findings hold true among skilled individuals, as training and expertise may significantly influence the activity patterns of brain regions and motor performance70,71. As previously noted, despite over two decades of research in this area, we continue to advocate for more detailed investigations. Such efforts are essential for clarifying the effects of attentional focus, identifying relevant moderators or mediators, and moving away from generalized assumptions such as the idea that an external focus is universally more effective. Further research is necessary, as evidence of publication bias in the external focus literature has been reported72. Additionally, the observed heterogeneity across studies indicates that the effectiveness of attentional focus likely depends on contextual factors not yet fully understood, such as motivation, confidence, and environmental conditions72. Understanding these moderators will help coaches customize the type and timing of attentional cues to fit individual athletes and specific contexts. Such personalized coaching approaches can improve motor learning, skill acquisition, and overall performance, advancing evidence-based practice and athlete development across diverse populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available upon request from corresponding author.

References

Schmidt, R. A., Lee, T. D., Winstein, C., Wulf, G. & Zelaznik, H. N. Motor learning concepts an research methods. In Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis 6th edn (eds Schmidt, R. A. et al.) 283–302 (Human Kinetics, 2018).

Magill, R. A. & Anderson, D. Motor Learning and Control: Concepts and Applications (McGraw-Hill Education, 2020).

Wulf, G. Attentional focus and motor learning: a review of 15 years. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 6(1), 77–104 (2013).

Chen, T. T., Mak, T. C. T., Ng, S. S. M. & Wong, T. W. L. Attentional focus strategies to improve motor performance in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(5), 4047 (2023).

Chua, L.-K., Jimenez-Diaz, J., Lewthwaite, R., Kim, T. & Wulf, G. Superiority of external attentional focus for motor performance and learning: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 147(6), 618–645 (2021).

Lohse, K. R., Sherwood, D. E. & Healy, A. F. How changing the focus of attention affects performance, kinematics, and electromyography in dart throwing. Hum. Mov. Sci. 29(4), 542–555 (2010).

da Silva, G. M. & Bezerra, M. E. C. External focus in long jump performance: A systematic review. Mot. Control 25(1), 136–149 (2020).

Kim, T., Jimenez-Diaz, J. & Chen, J. The effect of attentional focus in balancing tasks: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Human Sport Exerc. 12(2), 463–479 (2017).

Wulf, G., Chiviacowsky, S., Schiller, E. & Ávila, L. T. G. Frequent external-focus feedback enhances motor learning. Front. Psychol. 1, 190 (2010).

Southard, D. Attentional focus and control parameter: Effect on throwing pattern and performance. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 82(4), 652–666 (2011).

Zachry, T. L. Effects of Attentional Focus on Kinematics and Muscle Activation Patterns as a Function of Expertise (University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2005).

Chiviacowsky, S., Wulf, G. & Ávila, L. An external focus of attention enhances motor learning in children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 57(7), 627–634 (2013).

Samadi, Z., Abedanzadeh, R., Norouzi, E. & Abdollahipour, R. An external focus promotes motor learning of an aiming task in individuals with hearing impairments. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 24(8), 1143–1151 (2024).

Abdollahipour, R., Land, W. M., Cereser, A. & Chiviacowsky, S. External relative to internal attentional focus enhances motor performance and learning in visually impaired individuals. Disabil. Rehabil. 42(18), 2621–2630 (2020).

McNamara, S. W., Becker, K. A., Weigel, W., Marcy, P. & Haegele, J. Influence of attentional focus instructions on motor performance among adolescents with severe visual impairment. Percept. Mot. Skills 126(6), 1145–1157 (2019).

Wang, K.-P. et al. Superior performance in skilled golfers characterized by dynamic neuromotor processes related to attentional focus. Front. Psychol. 12, 633228 (2021).

Wulf, G., McNevin, N. & Shea, C. The automaticity of complex motor skill learning as a function of attentional focus. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 54(4), 1143–1154 (2001).

Wulf, G., Shea, C. & Park, J.-H. Attention and motor performance: Preferences for and advantages of an external focus. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 72(4), 335–344 (2001).

Vereijken, B., Emmerik, R., Whiting, H. & Newell, K. M. Free(z)ing degrees of freedom in skill acquisition. J. Motor Behav. 24(1), 133–142 (1992).

Kal, E., Van der Kamp, J. & Houdijk, H. External attentional focus enhances movement automatization: A comprehensive test of the constrained action hypothesis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 32(4), 527–539 (2013).

Allingham, E. & Wöllner, C. Effects of attentional focus on motor performance and physiology in a slow-motion violin bow-control task: evidence for the constrained action hypothesis in bowed string technique. J. Res. Music Educ. 70(2), 168–189 (2022).

Mousavi, S. M., Salehi, H. & Iwatsuki, T. Gender stereotype threat and motor learning: Exploring its impact, underlying mechanisms, and attentional focus pathways for mitigation. Hum. Mov. Sci. 101, 103357 (2025).

Wulf, G. & Lewthwaite, R. Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 23(5), 1382–1414 (2016).

An, J. & Wulf, G. Golf skill learning: An external focus of attention enhances performance and motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 70, 102563 (2024).

Ghorbani, S., Dana, A. & Fallah, Z. The effects of external and internal focus of attention on motor learning and promoting learner’s focus. Biomed. Human Kinet. 11(1), 175–180 (2019).

Schücker, L., Anheier, W., Hagemann, N., Strauss, B. & Völker, K. On the optimal focus of attention for efficient running at high intensity. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2(3), 207 (2013).

Marchant, D., Greig, M. & Scott, C. Attentional focusing instructions influence force production and muscular activity during isokinetic elbow flexions. J. Strength Condition. Res. 23(8), 2358–2366 (2009).

Wulf, G., Dufek, J., Lozano, L. & Pettigrew, C. Increased jump height and reduced EMG activity with an external focus. Hum. Mov. Sci. 29(3), 440–448 (2010).

Neumann, D. & Brown, J. The effect of attentional focus strategy on physiological and motor performance during a sit-up exercise. J. Psychophysiol. 27, 7–15 (2013).

Becker, K. A., Georges, A. F. & Aiken, C. A. Considering a holistic focus of attention as an alternative to an external focus. J. Motor Learn. Dev. 7(2), 194–203 (2019).

Zhuravleva, T. & Aiken, C. Adopting a holistic focus of attention promotes adherence and improves performance in college track and field athletes. Hum. Mov. Sci. 88, 103055 (2023).

Abedanzadeh, R., Becker, K. & Mousavi, S. M. Both a holistic and external focus of attention enhance the learning of a badminton short serve. Psychol. Res. 86(1), 141–149 (2022).

Vafaeimanesh, N., Abedanzadeh, R. & Becker, K. Examining the effectiveness of focus of attention instructions on the learning of a badminton long serve in novice students: movement automaticity hypothesis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 22(6), 1390–1400 (2024).

Becker, K. A. & Hung, C.-J. Attentional focus influences sample entropy in a balancing task. Hum. Mov. Sci. 72, 102631 (2020).

Saemi, E., Amo-Aghaei, E., Moteshareie, E. & Yamada, M. An external focusing strategy was beneficial in experienced children but not in novices: The effect of external focus, internal focus, and holistic attention strategies. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 18(4), 1067–1073 (2023).

Abedanzadeh, R., Mousavi, S. M. & Becker, K. The effect of an internal, external and holistic focus on the learning of a soccer shooting task in male children. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 19, 17479541231198612 (2023).

Abdollahipour, R., Nieto, M. P., Psotta, R. & Wulf, G. External focus of attention and autonomy support have additive benefits for motor performance in children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 32, 17–24 (2017).

Coker, C. Kinematic effects of varying adolescents’ attentional instructions for standing long jump. Percept. Mot. Skills 125(6), 1093–1102 (2018).

Perreault, M. E. & French, K. E. External-focus feedback benefits free-throw learning in children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 86(4), 422–427 (2015).

Arjmandi, M. K., Samadi, H. & Jalilvand, M. Effects of attention focus guidelines on acquisition, retention and transmitting steps of movement form of Soccer chip shot in beginner children. Int. J. Basic Sci. Appl. Res. 2, 315–320 (2013).

Emanuel, M., Jarus, T. & Bart, O. Effect of focus of attention and age on motor acquisition, retention, and transfer: A randomized trial. Phys. Ther. 88(2), 251–260 (2008).

Petranek, L. J., Bolter, N. D. & Bell, K. Attentional focus and feedback frequency among first graders in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 38(3), 199–206 (2019).

Palmer, K. K., Matsuyama, A. L., Irwin, J. M., Porter, J. M. & Robinson, L. E. The effect of attentional focus cues on object control performance in elementary children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 22(6), 580–588 (2017).

Perreault, M. E. & French, K. E. Differences in children’s thinking and learning during attentional focus instruction. Hum. Mov. Sci. 45, 154–160 (2016).

van Abswoude, F., Nuijen, N. B., van der Kamp, J. & Steenbergen, B. Individual differences influencing immediate effects of internal and external focus instructions on children’s motor performance. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 89(2), 190 (2018).

Wulf, G., Töllner, T. & Shea, C. H. Attentional focus effects as a function of task difficulty. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 78(3), 257–264 (2007).

Raisbeck, L., Yamada, M., Diekfuss, J. & Kuznetsov, N. The effects of attentional focus instructions and task difficulty in a paced fine motor skill. J. Mot. Behav. 52(3), 262–270 (2020).

Yamada, M., Lohse, K. R., Rhea, C. K., Schmitz, R. J. & Raisbeck, L. D. Practice—Not task difficulty—Mediated the focus of attention effect on a speed-accuracy tradeoff task. Percept. Mot. Skills 129(5), 1504–1524 (2022).

Wang, K.-P. et al. Successful motor performance of a difficult task: Reduced cognitive-motor coupling. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 11(2), 174 (2022).

Li, D. et al. Neuromotor mechanisms of successful football penalty kicking: an EEG pilot study. Front. Psychol. 16, 1452443 (2025).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39(2), 175–191 (2007).

Nicklas, A., Rein, R., Noël, B. & Klatt, S. A meta-analysis on immediate effects of attentional focus on motor tasks performance. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 17, 1–36 (2022).

Li, D., Zhang, L., Yue, X., Memmert, D. & Zhang, Y. Effect of attentional focus on sprint performance: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(10), 6254 (2022).

Mousavi, S. M., Salehi, H., Iwatsuki, T., Velayati, F. & Deshayes, M. Motor skill learning in Iranian girls: Effects of a relatively long induction of gender stereotypes. Sex Roles 89(3), 174–185 (2023).

Barbieri, F. A., Gobbi, L. T., Santiago, P. R. & Cunha, S. A. Performance comparisons of the kicking of stationary and rolling balls in a futsal context. Sports Biomech. 9(1), 1–15 (2010).

Mousavi, S. M. & Soltanifar, S. Do gender stereotype threats have a spillover effect on motor tasks among children? A mixed-model design investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 76, 102775 (2025).

Singh, H. & Wulf, G. The distance effect and level of expertise: Is the optimal external focus different for low-skilled and high-skilled performers?. Hum. Mov. Sci. 73, 102663 (2020).

Singh, H., Shih, H. T., Kal, E., Bennett, T. & Wulf, G. A distal external focus of attention facilitates compensatory coordination of body parts. J. Sports Sci. 40(20), 2282–2291 (2022).

Banks, S., Sproule, J., Higgins, P. & Wulf, G. Forward thinking: When a distal external focus makes you faster. Hum. Mov. Sci. 74, 102708 (2020).

Bell, J. J. & Hardy, J. Effects of attentional focus on skilled performance in golf. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 21(2), 163–177 (2009).

Łuba-Arnista, W. et al. Is holistic focus of attention equally effective to external focus in performing accuracy of table tennis forehand stroke in low-skilled players?. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 17(1), 81 (2025).

Niźnikowski, T. et al. An external focus of attention enhances table tennis backhand stroke accuracy in low-skilled players. PLoS ONE 17(12), e0274717 (2022).

Roberts, J. W. & Lawrence, G. P. Impact of attentional focus on motor performance within the context of “early” limb regulation and “late” target control. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 198, 102864 (2019).

Plaza, M., Boiché, J., Brunel, L. & Ruchaud, F. Sport = Male… but not all sports: Investigating the gender stereotypes of sport activities at the explicit and implicit levels. Sex Roles 76(3–4), 202–217 (2017).

Hively, K. & El-Alayli, A. “You throw like a girl:” The effect of stereotype threat on women’s athletic performance and gender stereotypes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 15(1), 48–55 (2014).

Mousavi, S. M., Salehi, H. & Iwatsuki, T. Efficacy of an expectancy-based training in mitigating the effect of explicit gender stereotype activation on motor learning in children. Learn. Motiv. 90, 102119 (2025).

Schücker, L., Knopf, C., Strauss, B. & Hagemann, N. An internal focus of attention is not always as bad as its reputation: How specific aspects of internally focused attention do not hinder running efficiency. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 36(3), 233–243 (2014).

Vitali, F. et al. Action monitoring through external or internal focus of attention does not impair endurance performance. Front Psychol. 10, 535 (2019).

Mousavi, S. M., Valtr, L., Maruo, K., Mafakher, L., Laurin, R., Abdollahipour, R., et al. Effects of gender stereotype threat on motor performance, cognitive anxiety, and gaze behavior: Highlighting the role of context. Cognit. Process. 1–13 (2025).

Lu, G., Hagan, J. E., Cheng, M.-Y., Li, D. & Wang, K. P. Amateurs exhibit greater psychomotor efficiency than novices: Evidence from EEG during a visuomotor Task. Front. Psychol. 16, 1436549 (2025).

Wang, K. P., Yu, C. L., Shen, C., Schack, T. & Hung, T. M. A longitudinal study of the effect of visuomotor learning on functional brain connectivity. Psychophysiology 61(5), e14510 (2024).

McKay, B. et al. Reporting bias, not external focus: A robust Bayesian meta-analysis and systematic review of the external focus of attention literature. Psychol. Bull. 150(11), 1347 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We want to extend our heartfelt gratitude to the children who participated in this study and to their guardians for their kind cooperation and willingness to allow their children’s participation.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. A: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. R.A: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Formal analysis, Review, and editing—original draft. S.MR.M: Review, and editing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz’s ethics committee. Informed consent forms were acquired from the parents /guardians, and verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdi, G.M., Abedanzadeh, R. & Mousavi, S.M. Attentional focus strategies and motor performance in young adolescents investigating role of task difficulty. Sci Rep 15, 35818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19862-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19862-2