Abstract

Excessive sighs have been described as one type of dysfunctional breathing (DB). Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is one of the diagnostic options for DB and allows for a subjective evaluation of sighs. However, no validated method exists to automatically quantify sighs during CPET. We aimed to develop such a method. We used two Swiss cohorts of patients with persistent dyspnea after SARS-CoV-2 infection using CPET. In the derivation cohort (n = 48), we tested different filters to find the one that was the least influenced by outliers of tidal volume (VT) using a subjective approach. The selected filter (rolling median of 15 values) was applied in the validation cohort (n = 77) to detect spikes of VT above 2 times the value of the associated centered filtered value. Every automatically detected spike of VT from the cohort was analyzed by two experienced raters using continuous volume and flow-over-time graphs reconstructed from high resolution data acquisition. In the validation cohort, 203 automatically detected spikes of VT were visually analyzed by two raters. Of the 203 detected spikes, 199 corresponded to a sigh. The Cohen’s Kappa (95% CI) between the raters was 0.89 (0.67–1). In conclusion, we developed a simple automated method for the objective quantification of sighs during CPET. It could be used to establish normative values of sighs during CPET and explore the associations between sighs and symptoms of patients with DB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DB is typically defined by the presence of compatible symptoms with an abnormal breathing pattern and the exclusion of cardio-pulmonary or metabolic causes fully explaining these symptoms1. Different types of abnormal breathing patterns were proposed including hyperventilation and erratic breathing, associated or not with sighs1.

Sighs are normally generated unconsciously in the pre-Bötzinger complex, a structure in the brainstem included in the respiratory centers, which also generates normal inspiration2. Sighs typically occur due to a second burst generated in the pre-Bötzinger complex immediately after the initial burst, causing an augmented inspiration2. They are therefore characterized by a spontaneous deep inspiration (i.e., an inspiration on top of an inspiration), which is usually define as more than twice the “average” volume of a normal tidal volume (VT)3,4,5. They occur spontaneously during wake and sleep states, where they are thought to participate in alveoli reinflation, psychophysiological resetting, and arousal5,6. Sighs increase with sustained attention and emotions such as sadness, exhaustion, stress, relaxation, relief, and anxiety4,7,8,9,10. They can also increase in response to various emotional and physiological stimuli such as hypoxia and hypercapnia11. In anxiety disorders and dysfunctional breathing (DB), sighs can become abnormally frequent12,13. When sighs become excessive, they are thought to contribute to symptoms characteristic of DB such as dyspnea, dizzy spells and palpitations1,3,5,14,15. These symptoms are hypothesized to be caused by mechanisms such as hyperventilation, abnormal neuro-mechanical coupling, and abnormal subjective awareness of the breathing mechanisms1,3 and generally have a significant impact on patients. For example, patients with DB diagnosed after SARS-CoV-2 infection have been shown to experience poor quality of life, sometimes more severe than that of patients with advanced respiratory diseases12.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) has been used to evaluate dyspnea from unclear origins and to identify the main factors limiting exercise16. It also allows the detection of some DB patterns17,18. Notably, CPET has been widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic for the evaluation of the post COVID Condition (PCC), where erratic breathing, hyperventilation, and excessive sighs were described12,19,20,21. CPET has been a central tool for diagnosing these conditions and understanding symptoms persisting after COVID-1922. Hyperventilation during CPET is defined using objective markers, including an elevated ventilation to CO2 production ratio (VE/VCO2) and gas exchange parameters such as pH, arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2), and end-tidal CO2 pressure18. In contrast, erratic breathing and frequent sighs during CPET are defined subjectively based on the visual evaluation of breathing patterns using unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs17. This subjective assessment introduces several problems, including inter- and intra-rater variability and the inability to easily quantify and systematically evaluate these breathing patterns. Therefore, while frequent sighs were observed in some patients with DB after COVID-19, these findings were observer dependent, and sighs were not quantified12,19. No objective quantification was performed because no existing method to automatically detect sighs during CPET exists. Until now, most studies evaluating sighs have used inductive thoraco-abdominal plethysmography or flowmeters during sleep recordings4,6,8,9,10. An automatic, observer-independent methodology to detect sighs during CPET could help develop normative values for sighs during this test and assess associations between sighs and symptoms of DB. Such method would be of help for the diagnosis of DB through automatic detection of excessive sighing.

Deep inspirations can be easily recognized by trained observers on continuous volume-over-time and flow-over-time curves and are characterized by an increased VT associated with a relatively constant inspiratory flow in adults4. They can be differentiated from other events such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing, or speaking because these abnormalities usually do not induce an increase in VT and systematically cause changes in the inspiratory or expiratory flows. Unfortunately, continuous volume-over-time and flow-over-time curves are not stored by most CPET softwares. On the other hand, most CPET softwares save unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data, which contain a summary of each respiratory cycle. The ideal method to automatically detect sighs should ideally use unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data, as this could be used for all CPET, retrospectively and prospectively.

There are many challenges in developing a method to quantify sighs during CPET. First, because exercise induces a trend in the VT, the mean of all VT points cannot be used as a reference value to identify outliers such as sigh which are defined as “VT twice larger than the average normal breathing”11. Therefore, a method suited for the data trend should be used. Second, in subjects with frequent sighs, a metric that is not influenced by outliers should be found. Third, the sigh detection method should be specific. Spikes of VT extracted from unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data should correspond to deep inspirations and not artifacts or other phenomena.

In this work, our goal was to develop an automatic method to objectively identify sighs during CPET while considering the above-mentioned challenges.

Methods

The development of the method followed a three-step process (extensively detailed after) using two distinct cohorts:

-

In the validation cohort, among nine filtering techniques, we aimed to identify the filter least influenced by VT outliers.

-

The selected filter (i.e., a 15-point rolling median) was then applied in the derivation cohort to detect VT spikes using unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data.

-

Finally, all detected spikes from the validation cohort were reviewed by two independent, blinded raters using high-resolution volume-over-time and flow-over-time graphs to confirm whether each detected VT spike corresponded to a true sigh.

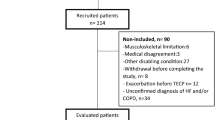

Patients

We used the data from two Swiss cohorts of patients with PCC previously published12,20. All patients signed an informed consent form, and the collection of data was approved by the local ethical committee (BASEC 2020-01457, CER VD, ID: 2021-01698).

The CPET protocols for these cohorts have been previously published12,20,23. Both centers used an incremental ramp test on an electromagnetic cyclo-ergometer (Variobike 500, ergoline GmbH, Bitz, Germany) with a 12 leads ECG unit (Cardiopart 12 Blue ECGpro, AMEDTEC Meditzintecknik Aue GmbH, Aue, Germany) and pulse oximeter at the fingertip (WristOx2 3150 Nonin Medical Inc, Plymouth, MN). Respiratory gas and flows were measured breath-by-breath (Ergostik, Geratherm Respiratory GmbH, Bad Kissingen Germany). Calibration was performed with a 3L syringe and two gases of known concentration. All CPETs were performed with the following steps: rest phase of 2 min or more (until stable gas exchange was achieved), warming phase of 2 min (derivation cohort) or 3 min (validation cohort) of unloading pedaling or minimal load (up to 50W), an exercise duration of 8–12 min and a recuperation phase of 3–5 min. Inspiratory capacity maneuvers were purposefully not performed in both cohorts, since DB was one of the suspected mechanisms of dyspnea generation and that it was thought that inspiratory capacity could diminish the ability of CPET to detect DB12,20,23.

The first cohort including only patients diagnosed with DB after COVID-19 infection was used for derivation of the most appropriate method for automatic sigh detection12. In this cohort, only unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data is available. The full cohort description, including participant characteristics, is detailed elsewhere12.

The second cohort was used for validation of the most appropriate automatic filter20. It contains data from patients with persistent and unexplained respiratory symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection, referred for CPET. In addition to the traditional CPET acquisition of unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data, continuous records of flow and gas using 125 Hertz high-resolution acquisition were stored at the specific request of the investigators. These high-resolution data were available for 77 of the 79 patients included. The full cohort description, including participant characteristics, is detailed in a previous publication20.

For both cohorts, unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data was extracted as generated by the manufacturer software (Geratherm®, Germany). Using this data, unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs of VT over time were created. The use of unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs has been previously described for the assessment of breathing dispersion and sighs17,19,23. With unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs, an outlier in VT theoretically represents a larger VT, which in our experience typically corresponds to a sigh (i.e. deep inspiration). Figure 1 illustrates how unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data graphs are obtained from continuous volume-over-time graphs and a possible representation of unfiltered cycle-by-cycle VT over time graphs with dots connected. The dots connection appears useful to illustrate the temporal sequence between the dots, but it might also confuse some readers by giving the false impression that the VT points are truly “linked” together, forming a continuous volume-over-time graph (which is not the case, as shown in Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows an example of reconstructions from a real patient with excessive sighs using both high-resolution representations of volume-over-time and unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs.

From high-resolution volume-over-time graphs to unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data of VT over time graphs. The graph above represents high resolution (e.g. 125 Hz) VT over time data; the graph under illustrates unfiltered cycle-by-cycle VT data where one point represents one respiratory cycle. Connecting the dots facilitates the visualization of the temporal order of the respiratory points but it is of importance to recognize that the dots are not actually connected. Indeed, as shown above, the subject goes from a volume of 0–1.5 L and not from a VT of 500 mL to 1.5 L. This is why we prefer a dash line to show the order of the respiratory cycle and not continuous lines.

Real patient example showing high resolution volume-over-time graph with corresponding unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data graph. The graph above represents high resolution volume over time graph; the graphs under illustrate unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs of VT where one point represents one respiratory cycle. On the left, unfiltered cycle-by-cycle is represented without connected dots and on the right with connected dots (i.e two possible representations of cycle-by-cycle data). The red squares on the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs correspond to the high-resolution data represented above.

Step 1: Choice of the automatic method for VT outliers’ detection

Sighs are classically defined by a doubling of the average VT of an individual. The “average” here does not refer to a specific metric and could be, for example, a geometric mean, arithmetic mean, or a median. Various methods can calculate the average trend of breathing parameters and achieve data smoothing. For instance, Geratherm® proposes three data filtering methods: (1) Mean filter = simple mean of n values; (2) Median filter = median of n values; (3) Complex filter = mean of a fixed number of values, excluding the two extreme values (n − 2).

These filters calculate a rolling average (mean, or median, or any statistic) over a rolling window of size n, where n is typically between 7 and 15. The centered value of the filter is defined as the value in the middle of the n values. For example, for a filter with 15 values, the centered value would be the 8th value with 7 values preceding it and 7 values after it.

A point was classified as an outlier of VT if the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle value exceeded a threshold of 2 times the associated filtered centered value of the evaluated filter. For the start and end of the data where no rolling filter values can be computed (e.g. first seven and last seven values for a 15 values filter), we extrapolated from the first and last complete windows respectively. The comparison of unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data with their corresponding filtered data using different filter types and values of n = 15 is illustrated in a fictive example in Table 1.

Using cohort 1, we tested the various filters provided by Geratherm® to determine which filter was least influenced by the outliers and the most stable to follow the “average” VT. This was considered as a crucial step, since in patients with frequent sighs, the use of a filter can be highly influenced by outliers and lead to a reduced discriminating ability of the method. Using R software, sighs were identified if matching the above definition and visually marked. Three investigators (LG, CJ, POB) evaluated individual combined graphical representations of filtered and unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data of each subject to judge the influence of outliers using the following filters: mean of 7, 11 and 15 values, median of 7, 11 and 15 values, complex filters of 7, 11 and 15 values.

Steps 2 and 3: validation of the sigh identification method

In step one, we found that the rolling median filter of 15 values was the most stable filter and the least influenced by outlier values as compared to all the other tested filters (see results and discussion). We used this filter to define outliers of VT as every unfiltered cycle-by-cycle value that exceeded a threshold of 2 times the associated filtered value of the rolling median filter of 15 values (step 2). Every outlier of VT was then visually evaluated by two raters using high resolution volume-over-time and flow-over-time data using the methodology as explained below (step 3).

Using the high-resolution flow data, we reconstructed the respiratory cycles as obtained from the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data from the Geratherm® software. First, we removed any drift from the high-resolution flow data using a high-pass Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.03 Hz. Volume-over-time was computed as the integral of flow-over-time. Cycles were delimited by the lowest and highest points of each respiratory cycle considering a minimal volume variation of more than 150 mL to define a new respiratory cycle. To match the respiratory cycles obtained using the high-resolution signal to those acquired by the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data from Geratherm®, we used cross-correlations between the cycle durations computed from the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data from Geratherm® software using a window of 100 respiratory cycles. The sequence with the highest cross-correlation was used to synchronize both time series. After the best initial match was found, we moved forwards and backwards in the time series to link each respiratory cycle reconstructed from the high-resolution data to its corresponding respiratory cycle from the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data. For low amplitude cycles where no clear cycle boundary was visible in the volume-over-time curve (i.e. extended periods of near zero flow with no prominent local minima), we used the cycle values from the Geratherm® software data to reproduce the cycles and enable comparison of the resulting data series. A match dataset was considered when the volumes of the cycles extracted from the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data equaled the Geratherm® software data after rounding to the same number of digits.

Once both time series were matched (unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data and high-resolution data), every outlier detected by the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data from Geratherm® software were evaluated using the corresponding match from the high-resolution data acquisition. Two experienced evaluators with expertise in respectively CPET and non-invasive ventilation (LG and CC) independently analyzed each detected spike of VT and scored each spike as caused by a deep inspiration or another phenomenon. Cohen’s kappa coefficient between the two independent raters was calculated and a contingency 2 × 2 table containing the rating of the two raters was produced. Disagreements on discordant ratings of deep inspirations were resolved through discussion. We reported the total number of outliers representing deep inspirations as opposed to other phenomena assessed after consensus. For any outlier not thought to represent a deep inspiration by consensus, a qualitative description of the phenomenon was provided.

The scripts used to generate the rolling median filter and detect spike of VT and to define respiratory cycle and to match the high-resolution data to the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data are given in the supplementary material. Stata/BE 18.0 was used for the descriptive statistical analyses. Statistical software R (version 4.2.2) was used to analyze the different filters (derivation cohort). Jupyterlite online version was used for the manual analysis of every spike of tidal volume (https://jupyterlite.readthedocs.io/en/stable/_static/tree/index.html).

Results

The basic demographical characteristics of both cohorts are shown in Table 2. The 2 cohorts were composed predominantly of women with a mean age of around 50. The validation cohort contained more people hospitalized for severe COVID than the derivation cohort. They also had more comorbidities. Their pulmonary function tests were, in average, in the normal range as expected for a diagnosis of DB. Their exercise capacity was at the lower limits of normal.

Step 1: Derivation of the filter least influenced by outliers of VT (derivation cohort)

Among all tested filters, the median filter of 15 values was the most stable and the least influenced by outlier values as compared to all the other tested filters. The example of unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graphs from two patients with the automatic detection of spike of VT using the median filter of 15 points is shown in Fig. 3. Using the median filter of 15 points in the first cohort, the median (IQR) number of outliers of VT was 4 (2, 7). The total number of outliers of VT was of 214. Table 3 summarizes the number of detected VT outliers for all tested filters, showing that the median filter with a window of 15 points detected the highest number of VT outliers. As expected, the median, compared to the mean, was less influenced by VT outliers and therefore led to the detection of more VT outliers. This is illustrated in Fig. 4. This was also true when using complex filters. In some exceptional cases, the median of 15 values was less influenced by VT outliers than the median of 7 values, as shown in Fig. 4, leading to a slightly higher number of detected sighs (214 compared to 207). There was little difference between using a median with a window of 11 or 15 points, with 213 versus 214 VT outliers detected.

The same patient is represented as in Fig. 3B. In (A), the purple line represents the mean filter of 15 tidal volume values. In figure (B), the orange line represents the median filter of 7 values filter. In both A and B, the green line represents the median filter of 15 values. Each grey dot represents one respiratory cycle. In figure (A) and (B), detected spike of VT are not shown because two filters are represented. Figure (A) illustrates that the mean filter (purple line) is more influenced by outliers of VT than the median filter (green line) for a same window size (15). The detection of sighs using the mean filter of 15 values is of only 4 spikes of VT detected in this patient. This contrasts with Fig. 3B from the manuscript using a median filter of 15 values and detecting 17 spikes of VT. In figure (B), the frequency of the sighs is so high (more than 1 sigh every 2 breaths on a sequence of 7 breaths) that the centred value of the 7 points median filter reaches the value of the sighs two times as shown by the two spikes of the orange line. When the value of the filter represents the value of the sigh, the method will be unable to detect sighs. The median filter of 7 values is globally less stable than the median filter of 15 values which globally follows the underlying breathing without being influenced by the sighs. While this extreme situation of instability is infrequent, it leads to less sighs’ detection using a median filter using smaller window of filtering (in this example 7 compared to 15).

Step 2 and 3: Application of the filter to detect outliers of VT and validation of sighs detection in the validation cohort

Applying the median filter of 15 points to the 77 patients analyzed, 47 patients had at least 1 outlier of VT that could be analyzed using correlated high-resolution data. In these 47 patients, the median (IQR) number of outliers of VT was 2 (1, 5). The total number of outliers evaluated were of 203. The total number of outliers of VT detected in both cohort is summarized in Table 4.

After reaching a consensus between the two raters, the total number of outliers identified as sighs were of 199 over the 203 analyzed breaths. The two independent and blinded raters disagreed on one spike of tidal volume, which was scored as a flow artifact by scorer 1 and a sigh by scorer 2. After discussion, it was considered that the spike of tidal volume corresponded to a sigh. The two-scorers agreed on 4 other phenomena not attributable to sighs. The observed events not related to sigh were: 3 abnormal cycles mainly due to an excessive expiration, 1 abnormal cycle due to an undetectable inspiratory flow with intermittent expiratory flow. This phenomenon was probably caused by transient removal of the nose clip with nasal inspiration and buccal expiration causing aberrant respiratory cycles. The supplementary material (Figs. S1, S2, S3) shows graphically the 4 spikes of tidal volume detected by our algorithm but considered to be false positive sighs detection by the two independent evaluators (CC and LG). The resulting contingency 2 × 2 table of the two scorers is shown in Table 5. The calculated Cohen’s kappa coefficient (95% CI) was 0.89 (0.67–1).

Figure 5 shows the flow and volume-over-time curve obtained from high-resolution data. A regular breathing is shown in Fig. 5A and two typical morphological sighs are shown in Fig. 5B with an increased inspiratory volume often followed by a slightly reduced functional residual capacity. The Fig. 6 summarizes the methodological steps and results in the development of the method, including patients included and excluded from each analysis in both cohorts.

Example of a regular breathing (A) and of two sighs (B). High resolution (125 Hz) flow-over-time (red) data and volume-over-time (blue) data. Spikes of tidal volume are detected on the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data of Geratherm® using unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data compared to centered value of the rolling median of 15 points. Cross-correlation of Geratherm® unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data with the high-resolution data allowed the analysis of each spike of tidal volume detected, which are illustrated by a black vertical line delimitating the start of the spike of VT. In figure B, Individual readings of the two spikes of VT by two independent scorers confirmed two deep inspirations representing sighs and not another phenomenon.

Discussion

In this article, we propose for the first time an observer independent method that identifies and quantifies sighs during CPET. The development of this method followed a three-steps approach. First, out of 9 filtering techniques, we found, in the validation cohort, that the rolling median of 15 points was the filtering method which was the least influenced by outliers of VT. The rolling median of 15 points was then used in the derivation cohort to detect the spikes of VT using unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data. Finally, all the detected spikes from the validation cohort were analyzed using high-resolution volume-over-time and flow-over-time graphs to confirm that the method correctly identified each detected spike of VT as a true sigh. In 199 over the 203 detected spikes, the method correctly identified sighs as assessed by two independent and blinded raters.

The rolling median of 15 points method was stable across the 48 evaluated CPET from the derivation cohort and was less influenced by outliers than the rolling mean or rolling complex filters. This is illustrated in Fig. 4A comparing the mean and median filters. This was expected since the median is a metric less influenced by outliers than the mean. Also, the median is commonly used when assessing data with non-symmetric distributions. Bimodal distribution of VT is typical in patients with excessive sighs associated with DB as shown in supplementary Fig. S4. The first mode of VT describes the baseline breathing, which can be considered as a physiologic response to the metabolic demand and the second mode represents the sighs. In this context, the use of the mean filter will result in the omission of a significant number of sighs, especially if the subject has a high sighs’ frequency. As expected, filtering methods with a higher number of values were more stable and less influenced by outliers than filters with lower number of values. The phenomenon is graphically illustrated in Fig. 4B where the median filters of 7 values and 15 values are compared on the same CPET. The median method using a smaller window of 7 points is missing some VT outliers.

The two scorers found discordances between the visual and automated analysis of VT spikes in 4 cases (Figs. S1, S2, S3). One plausible explanation is related to the measure of VT in Geratherm® CPET softwares. Since the tidal volume is usually calculated as the mean of the inspiratory and expiratory volumes, a spike of tidal volume will be detected whether it is caused by an increased inspiratory volume, an increased expiratory volume or both. Usually sighs lead to an increase of both the inspiratory and expiratory volumes proportionally. However, a deep expiration from the functional residual capacity will artificially lead to a spike of VT, which might be counted as a sigh if the overall tidal volume reaches the threshold of twice the average VT. One way to assure that all detected outliers of VT are sighs and not representing other phenomenon could be to manually analyze outliers that have a large difference between inspiratory and expiratory volume on the cycle-by-cycle raw data. We think that the automatic method could still be applied without systematic verification of the inspiratory and expiratory volumes. Indeed, in our dataset we demonstrated that fully automatic detection of sighs was correct in 199 out of 203 cases (98%). We consider this a clinically acceptable margin of error, particularly since the false identification of a sigh has limited clinical consequences. In clinical practice, diagnosing frequent sighs in an individual with an otherwise normal breathing pattern would lead to the prescription of specific physiotherapy, which is a harmless intervention. This seems however unlikely in the context of an error of 2%. In a research context, a precision of 98% also appears perfectly acceptable for evaluating associations between sighs and symptoms.

The definition of a sigh as an inspiration more than twice the average tidal volume is based on expert opinion and is somewhat arbitrary. Some sighs have been reported just below 2 times the average VT and it is unclear whether another cutoff would be more appropriate3,4,5. Using a relative cutoff based on the baseline tidal volume leads to the detection of variable phenomena. For example, for a patient with a baseline VT of 700 mL, a sigh is scored at volumes above 1400 mL, while for a patient with a baseline volume of 350 mL, a sigh is scored at volumes above 700 mL. Also, since the method scores one sigh independently of its amplitude above a certain threshold, it might be useful to record the amplitude of each sigh in addition to the number of sighs for a better understanding of this phenomenon in future studies. In our experience, some patients have sighs just exceeding this two times threshold, while others have sighs of more than 4 L.

No gold standard exists in the evaluation of sighs, which precluded the evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of our method to detect sighs. Defining sighs on a continuous volume-over-time loop without using cutoff of volume variations would lead to great inter-variability between scorers. Given the lack of universally accepted definition of sigh at rest and at exercise, the comparison of an objective, automated sigh detection method with human eye would not be relevant. For research and clinic, we think however that automated methods, such as the one described here constitute a necessary step to draw the characteristics and define sighs. Our method offers an objective approach; however, the exact cutoff that should be used remains uncertain. One way to approach this problem could be to correlate different cutoffs with symptoms in patients with DB. To test that, one could easily use our code and modified the cutoff for a sigh definition by modifying the value of “2” in the appropriate line of code (i.e. supplementary material, R code for creating the moving median filter, # identify for each cycle whether it is deemed a sigh (1) or not (0)). It is possible that using this approach we might better define what abnormal sighing means in terms of volume and frequency. Nevertheless, we recommend the visual inspection of appropriate graphs (i.e. as depicted in Fig. 3) to judge the clinical accuracy of the sigh as detected by the objective, automated method.

Using the definition of sighs as two times the average VT, some “sighs” during exercise will obviously be missed as the average VT increases. This is illustrated in supplementary material S5 where the value of sighs of most individuals is stable during exercise, whereas the underlying VT increases. We did not develop a method to capture these sighs during exercise because it is unclear whether these phenomena are of any physiopathological significance and because no definition of sighs during exercise has yet been proposed. Therefore, the method essentially captures sighs during the rest, warm-up and start of exercise. Its capacity to detect spikes of VT during exercise progressively diminishes as exercise intensity increases. Since the normal expected number of sighs will vary according to the time where sighs are likely to occur, it seems logical to normalize the number of sighs detected over the time where sighs can be detected (essentially rest, warm-up and beginning of exercise). This will be necessary when comparing the number of sighs across different exercise protocols. Although sighs will not be detected throughout the entire test, we still recommend performing the method for the full duration of the exercise. This facilitates the generation of graphical representations, makes it easier to detect when sighs start and end, and allows for normalization during the periods when they occur, ideally with graphical verification. Overall, we think that the rest phase might be the most interesting phase for the analysis of sighs. In our clinical practice, we tend to extend the duration of this phase when DB is suspected, allowing up to 5 min of quiet breathing before CPET is started.

We previously published an article validating a non-parametric regression method called LOESS to quantify dispersion around the trended parameter24. This method allows the calculation of the standard deviation around the trended value. SD are highly influenced by outliers of VT, and sighs represent outliers for VT. Usually, outliers are rare, but in patients with DB, sighs can become excessively frequent, contributing to most of the measured dispersion around the trended parameter. Therefore, the method we developed to quantify sighs is crucial for understanding the dispersion of VT. It could be used in addition to dispersion measurement to understand the cause of dispersion and to evaluate objectively whether high dispersion of VT is due to general dispersion or excessive sighs. In our experience, some patients have high dispersion of VT without sighs, some have excessive sighs and low dispersion of underlying VT, and some have both high dispersion of VT and excessive sighs. These situations might represent different clinical scenarios, with likely different physiopathologies. Also, breathing frequency, amplitude, and variability might be associated with the frequency of sighs. Nevertheless, this association remains poorly studied especially during CPET. The LOESS enables the evaluation of the dispersion of all breathing parameters including the breathing frequency and may help assess this association in the future, which could be important for understanding different phenotypes of DB. The strength of our study lies in the development of the first automatic method to objectively quantify sighs during CPET based on unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data. These data can be retrospectively acquired from all CPET software. This will allow researchers to evaluate sighs both prospectively and retrospectively using previously collected CPET data. We have developed a method that is not influenced by outliers, and able to follow the average VT parameter to define sighs. Using high-resolution (125 Hz) volume-over-time and flow-over-time data, we were able to demonstrate that almost every spike of VT on an unfiltered cycle-by-cycle graph corresponded to a sigh.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, inspiratory capacity maneuvers are frequently performed to understand mechanical constraints during exercise. If inspiratory capacity maneuvers are performed during CPET, it will be necessary to manually exclude the maneuvers detected as spike of VT from the automatic counting of sighs. Secondly, our methodology probably poorly differentiates yawning and sighs. However, yawning is in our experience uncommon during CPET.

Conclusions

We developed a simple automated method allowing an objective quantification of sighs during CPET using the median filtering of 15 points to detect spikes of VT on unfiltered cycle-by-cycle data. This method can be easily implemented in most CPET software. We believe that our method will help researchers to define normative values for sighs during CPET and contribute to the understanding of the associations between sighs and symptoms in persons living with dysfunctional breathing.

Data availability

The data availability statement concerning the patients of the first and second cohort are available elsewhere12,20. The statistical code allowing for the detection of sighs using the centered value of a rolling median filter of 15 value associated with unfiltered cycle-by-cycle value is available in the supplementary material and is free of use.

References

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., Niven, R. & Fowler, S. J. Dysfunctional breathing: A review of the literature and proposal for classification. Eur. Respir. Rev. 25, 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015 (2016).

Li, P. et al. The peptidergic control circuit for sighing. Nature 530, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16964 (2016).

Vlemincx, E., Severs, L. & Ramirez, J. M. The psychophysiology of the sigh: II: The sigh from the psychological perspective. Biol. Psychol. 173, 108386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108386 (2022).

Qureshi, M., Khalil, M., Kwiatkowski, K. & Alvaro, R. E. Morphology of sighs and their role in the control of breathing in preterm infants, term infants and adults. Neonatology 96, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1159/000201738 (2009).

Ramirez, J. M. The integrative role of the sigh in psychology, physiology, pathology, and neurobiology. Prog. Brain Res. 209, 91–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63274-6.00006-0 (2014).

Vlemincx, E., Van Diest, I., Lehrer, P. M., Aubert, A. E. & Van den Bergh, O. Respiratory variability preceding and following sighs: A resetter hypothesis. Biol. Psychol. 84, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.002 (2010).

Tobin, M. J. et al. Breathing patterns. 1. Normal subjects. Chest 84, 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.84.2.202 (1983).

Vlemincx, E., Taelman, J., De Peuter, S., Van Diest, I. & Van den Bergh, O. Sigh rate and respiratory variability during mental load and sustained attention. Psychophysiology 48, 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01043.x (2011).

Vlemincx, E. et al. Why do you sigh? Sigh rate during induced stress and relief. Psychophysiology 46, 1005–1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00842.x (2009).

Vlemincx, E., Taelman, J., Van Diest, I. & Van den Bergh, O. Take a deep breath: the relief effect of spontaneous and instructed sighs. Physiol. Behav. 101, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.015 (2010).

Severs, L. J., Vlemincx, E. & Ramirez, J. M. The psychophysiology of the sigh: I: The sigh from the physiological perspective. Biol. Psychol. 170, 108313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108313 (2022).

Genecand, L. et al. Dysfunctional breathing symptoms, functional impact and quality of life in patients with long COVID-19: A prospective case series. BMJ Open Respir. Res. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001770 (2023).

Tobin, M. J. et al. Breathing patterns. 2. Diseased subjects. Chest 84, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.84.3.286 (1983).

Prys-Picard, C. O., Kellett, F. & Niven, R. M. Disproportionate breathlessness associated with deep sighing breathing in a patient presenting with diff5icult-to-treat asthma. Chest 130, 1723–1725. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.6.1723 (2006).

Abelson, J. L., Weg, J. G., Nesse, R. M. & Curtis, G. C. Persistent respiratory irregularity in patients with panic disorder. Biol. Psychiatr. 49, 588–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01078-7 (2001).

Laveneziana, P., Di Paolo, M. & Palange, P. The clinical value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the modern era. Eur. Respir. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0187-2020 (2021).

Ionescu, M. F. et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the assessment of dysfunctional breathing. Front. Physiol. 11, 620955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.620955 (2020).

Watson, M., Ionescu, M. F., Sylvester, K. & Fuld, J. Minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production in patients with dysfunctional breathing. Eur. Respir. Rev. 30, 200182. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0182-2020 (2021).

Beurnier, A. et al. Functional respiratory complaints among COVID-19 survivors: A prospective cohort study. ERJ Open Res. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00063-2023 (2023).

Guerreiro, I. et al. Exercise ventilatory response after COVID-19: Comparison between ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00142.2023 (2023).

Motiejunaite, J. et al. Hyperventilation as one of the mechanisms of persistent dyspnoea in SARS-CoV-2 survivors. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01578-2021 (2021).

Durstenfeld, M. S. et al. Use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing to evaluate long COVID-19 symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2236057. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36057 (2022).

Fresard, I. et al. Dysfunctional breathing diagnosed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing in ‘long COVID’ patients with persistent dyspnoea. BMJ Open Respir. Res. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001126 (2022).

Genecand, L. et al. Comparing methods to measure the dispersion of breathing parameters during exercise testing: A simulation study based on real-life parameters from patients with dysfunctional breathing. Physiol. Rep. 13, e70233. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.70233 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who accepted to take part in the prospective case series and all the medical staff the made possible this prospective case series.

Funding

This study was supported by the “Ligue pulmonaire genevoise”, the “Fondation Rankers Hartmann”, the “Ligue pulmonaire valaisanne” and the “fondation Lancardis”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G conceived the study, performed the statistical analysis of the two independent raters, drafted the manuscript and handled the submission process. T.N created the platform of analysis allowing the interpretation of high-resolution data matched to the unfiltered cycle-by-cycle raw data from cohort 2. C.J designed the different filters, generated separated graphs with the different filters for all patients of cohort 1 and exposed the data. LG, CJ and POB visually analyzed all graphs from cohort 1 to determine which filter was the least influenced by outliers. CC and LG performed the independent rating of each spike of VT using the high-resolution data. S.T. helped with the collecting of data. P-O.B, I.F, M.A, and L.G collected the real-life data of the first cohort. I.G and F.L collected the data of the second cohort. All authors edited and revised the first draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The real-life parameters were based on a study involving human participants and was approved by (Commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain (CER VD), ID: 2021-01698). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part. All methods were done in accordance with relevant rules and guidelines.

Human and animal rights

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Genecand, L., Nibler, T., Guerreiro, I. et al. An objective method to detect sighs during cardio-pulmonary exercise testing. Sci Rep 15, 36744 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20654-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20654-x