Abstract

Successful restorative treatment depends on aesthetic, mechanical, and biological properties. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of Hydrogen Peroxide and Sodium Perborate on surface roughness and stain removal from stained ceramics. Thirty-two discs were prepared of feldspar (diameter 6.4 ± 0.2 mm, thickness 2.2 ± 0.1 mm). and lithium desilicated glass ceramic )diameter 7 ± 0.1 mm, thickness 2.2 ± 0.1 mm). Specimens were divided into four groups, based on the type of porcelain and bleaching agent used (n = 8). All the Specimens were immersed in (tea, yogurt, soda, orange juice, and Mulberry juice) respectively for 30 days. Then Hydrogen Peroxide 30% was applied to specimens for 2 h. Sodium Perborate was applied for 14 days/6 hours per day. CIEDE2000 parameters and surface roughness values were recorded at three times; initial baseline color, post staining, and post bleaching. Data were statistically analyzed using paired t-test and ANOVA. There was no significant difference in color changes (∆E002) and roughness changes values between all groups, but there was a significant increase in surface roughness in each group after staining and after bleaching. Also, the residual color values of all groups were below 1.8, with lithium disilicate ceramic treated with sodium perborate showing better color retrieval. Conclusion the bleaching agents reduced color change caused by discoloring solutions and caused an increase in surface roughness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental ceramics has two important properties: mimic natural appearance of teeth and low thermal and electrical conductivity. It also has well to excellent strength, but it remains brittle and may fracture suddenly when subjected to flexure or when is heated and cooled rapidly, and it can wear opposing teeth1. Mechanical and optical properties vary, depending on its microstructure. Based on their applications, dental ceramics are classified as: (1) Ceramic for metal-ceramic restorations, crowns, and bridges. (2) Ceramic for full-ceramic restorations, crowns, fillings, inlays, onlays, and veneers. (3) Ceramics for orthodontic brackets, dental implant abutments, and dental dentures2. Another classification of the ceramics is based on the manufacturing materials, as they are mainly divided into three categories3: 1.silicate ceramics which are nonmetallic inorganic ceramic materials containing a glass phase, which have good optical properties, high transparency, and an attractive and natural appearance3. Hence, the most commonly used silicate ceramics in the field of dental prosthetics are feldspar porcelain, leucite-enhanced glass ceramics, and lithium disilicate ceramics4., 2.polycrystalline ceramics with generally stronger mechanical proprtis than glass ceramics. In this type, no glass phase is present and all crystals are arranged in a dense conventional matrix5,6. 3. resin-based ceramics which are a new type of ceramic material that combine the advantages of ceramic and polymer materials. This composite material features a resin matrix based on inorganic ceramics. Therefore, resin-based ceramics are not ceramics in the strict sense, but they are ceramic-like materials3,7.

The dental ceramics mimic enamel and dentine colors which varies among people, in addition, the color of ceramic restorations itself varies according to many factors such as the thickness of porcelain, trademark, and condensation techniques, degree and number of firings, surface roughness, as the light reflects and scatters irregularly on rough and irregular surfaces, resulting changes in the color of the ceramic restoration8. Meanwhile, perception color of an object depends on nature body and nature light that falls on it, and received by the retina. Color properties are determined by body interaction with light. Light may be reflected, absorbed, or transmitted. Eye response is not similar for individuals, depending on factors such as age, general health, medications and fatigue1.

As the oral cavity is an aqueous environment, with variations in pH and the temperature due to the ingestion of different beverages and foods. The materials exposed to such variations can alter their esthetic and mechanical properties9. Moreover, plants and fruits contain bioactive compounds, including chromogenic polyphenols, which give fruits their specific color. An example of these is anthocyanins found in berries10. In tea leaves, it is called tannin11. Fruits also contain organic acids, such as citric acid and limonene in oranges, and malic acid and citric acid in berries12. Therefore, exposing porcelain to carbonic acids found in cola and organic acids found in citrus fruit juices and lactic acid in milk, led to chelation of some minerals from porcelain surface, causing a decrease in crystallinity and dissolve the silica network, then increased leaching of the pigments present in these solutions13.

In 1976, Commission Internationale de l`éclairage (CIE) established a uniform standard system that accurately calculates color change between two points. It relies on three color coordinates: L* represents brightness color in Munsell system, ranging from 0 to 100. B* and a* represent hue and chroma in Munsell system, a represents red-green axial, while b represents yellow-blue axial8. And to improve the correctness between instrumental and visual color assessments in industrial applications, a new CIELAB-based color-difference formula (CIEDE2000), has been proposed by CIE, recently14. The ∆E00 calculates color change between two points in a three-dimensional color space, by Eq. (1):

Restoration surface roughness affect not only color perception of the restoration, but it is also one of the most important factors to a long-term success. Roughness can lead to accumulation of plaque and food pigments, causing gingivitis, secondary caries, and poor aesthetic appearance15. Surface roughness can be measured using many numerical scales. Produced by a Profilometer roughness average (Ra) of a surface calculates average surface roughness, considering all protrusions and depressions within the measured distance on that surface16.

The effect of bleaching agents on ceramic colors and surface roughness can be explained due to their nature as an acid-based oxidants that release H + ions upon decomposition17. For example, Hydrogen peroxide is an unstable compound. Decomposing to water, active oxygen, and free radicals such as hydroxyl and perhydroxyl radicals. Sodium perborate, also decomposes after mixing with water to sodium metaborate, releasing nascent oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, which decomposes as previously mentioned18. When bleaching materials come into contact with porcelain surface, a reaction occurs between H + ions and porcelain’s metal ions, which induces chelation of metals from porcelain surface, and releases primarily Na + and K + ions, which are the fastest, followed by Ca+2, P+3, Al+3, and then Li + and Zn+ ions, which are the slowest19. Free radicals oxidize pigments present on porcelain surface or intra it. Pigments were destabilized and break the bonds between them to become shorter chains20. The wavelength of light reflected from them and the porcelain surface alters and shows different color21,22. In addition, the color change results from a change in the porcelain’s nature itself15. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of bleaching agents on surface roughness and color change of two different silicate ceramics: feldspar and lithium disilicate glass ceramics. And the null hypothesis of this study is bleaching agents don’t affect color properties and surface roughness of discolored ceramics.

Materials and methodes

Sample size determination

Sample size calculation was carried out using a statistical software (G*Power v3.1.9.2 for MacIntosh, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany) with the following input parameters for paired t test, effect size 0.65, α level 5%, 95% power, 12 groups, 3 measurements, correlation between measurements 0.50, and non-sphericity correction 0.75. Based on the calculations, a total sample size of 60 generated a power of 0.98, therefore the minimum sample size per group was 5.

Thirty-two specimens were prepared for total sample size, 16 specimens of feldspar)diameter 6.4 ± 0.2 mm, thickness 2.2 ± 0.1 mm). and 16 specimens of lithium disilicate glass ceramic (Emax press))diameter 7 ± 0.1 mm, thickness 2.2 ± 0.1 mm).

Specimens manufacturing

The group of feldspathic porcelain (Dentsply, USA) was constructed by a conventional method using sintering technique (Powder/liquid). The slurry produced was transferred into plastic mold. Lithium disilicate glass ceramic group (Vivadent Ivoclar, Germany) was prepared from a wax pattern, then heat-pressed (IPS Empress EP600; Ivoclar Vivadent AG). The specimens were polished (following the instructions of the manufacturer) and grounded using 600- 800-1000-1500 grit abrasive paper (Waterproof Abrasives papers, Thailand) under water. Specimens were coated with a layer of glaze and fired according to instructions of the manufacturer. The thickness of the specimens was checked using a caliper (Alpha Tools, Mannheim, Germany) for standardization.

Immersion protocol

All specimens were soaked in staining solutions respectively at the same time: Soda(Pepsi, Joud, Syria), Yogurt (New Park, Syria), Orange juice, Mulberry juice, Blake Tea (AlAttar, Syria) which was prepared as weighted 15 g in 300 mL of boiled water. These solutions were chosen based on the availability in the Syrian markets. Staining solutions were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C to stimulate human body temperature for 30 days \6 consecutive days for each one as each soaking day is equivalent to 30 days of consumption, and were replaced daily to avoid bacteria and yeast contamination. At the time of replacement, each disc of the sample was rinsed with water and dried with a paper towel before immersing back in solution. The whole immersion process was equivalent to 30 months of human consumption of the soaking solutions9.

Study groups

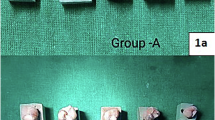

All specimens were divided into two main group after they were stained by immersing them in different solutions:

Group 1. stained Feldspar ceramic group (Fig. 1a, b).

Group 2. Stained Lithium disilicate ceramic group (Fig. 2a, b).

And after bleaching them with one of the bleaching agents (hydrogen peroxide, sodium perborate), The treated specimens were divided into four subgroups:

Group 1a: Stained feldspathic porcelain specimens bleached with 30% Hydrogen peroxide (HP) (Fig. 3).

Group 1b: Stained feldspathic porcelain specimens bleached with (SP) (Fig. 4).

Group 2a: Stained Lithium disilicate ceramic specimens bleached with 30% Hydrogen peroxide (HP) (Fig. 5).

Group 2b: Stained Lithium disilicate ceramic specimens bleached with (SP) (Fig. 6).

Preparation of hydrogen peroxide

Gel was made by stirring Carbopol, 7 g Carbopol powder in 100 ml water for 24 h. Powder particles absorbed water and their size increased to formulate a gel. An amount of 1 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide solution was mixed with a teaspoon of gel. Eight specimens from each ceramic group were treated with gel for 2 h (4 sessions, 30 min for each).

Preparation of sodium perborate

Sodium perborate grains were grounded and mixed with water drops to get a sticky consistency. Eight specimens from each ceramic group were treated with gel for 6 h\day for 14 days.

Roughness test

The specimens were positioned with their surfaces in contact with the diamond tip of a profilometer (TR200 INNOVATEST – USA). The baseline data for surface roughness were recorded by the profilometer. Each specimen was measured 3 times and the average baseline roughness (Ra) value was calculated. The same protocol of surface roughness measurement was followed after staining and after bleaching treatment. Changes on surface roughness were measured according to the equations:

∆ Ra1 = Ra1 -Ra2 (representing the difference between pre and post staining).

∆Ra2 = Ra2 - Ra3 (representing the difference between post staining and post bleaching).

Color test

The specimens were soaked in distilled water for 24 h before measurement. The color value of each specimen was evaluated using a spectrophotometer (VITA Easy Shade) on white background. Each specimen was measured 3 times and the average baseline values for L*, a*, and b* were calculated then chroma (c) and hue (h) values were calculated using the equation:

After the staining and bleaching treatment, color value was recorded by the spectrophotometer with the same parameters. The magnitude of the total color difference (ΔE00) was calculated using the following equation:

Where ΔL’, ΔC’, and ΔH’ are the changes in L*, C*, and H* after staining and after bleaching. KL, KC, KH are parametric weighting factors which is constant, and SL, SC, SH are weighting functions calculated according to the L, C, H. RT is the rotation term that accounts for interaction between Chroma and hue differences in the blue region14.

ΔE001 represented color change between pre and post staining, while ΔE002 represented color change between post staining and post bleaching, while ΔE003 represented color change between pre staining and post bleaching.

Residual color was calculated as the difference between (ΔE001) after staining and (ΔE003) after bleaching. Positive values nearer zero signifies that bleaching process was efficacy and recovery of the original color. Negative values suggests that bleaching was more effective than staining, resulting in restorations that are overly bleached. Data were compared to a reference color difference of 1.8; above this, differences in color become clinically unacceptable14.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected, tabulated and statistically analyzed using SPSS software (Version 25, IBM, USA). The Shapiro Wilk test was used to verify the normal distribution of data. An independent t-test was used to compare changes in color and surface roughness after staining between the two main groups. A paired t-test was used for comparison of L, a, b, c, h, Ra values in each sub-group. One-way AVOVA was used to identify differences in color change between after staining and after bleaching, residual color and surface roughness between all four subgroups and the Bonferroni post hoc test was used to detect differences between each two groups. For all statistical analyzes, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Pearson correlation was applied to investigate association between color parameters and surface roughness.

Results

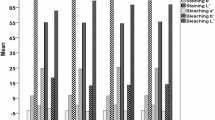

There was a significant increase in color change (ΔE00) after staining in feldspar ceramic group compared to the lithium disilicate glass ceramic group, also surface roughness change (ΔRa) after staining increased significantly in feldspar ceramic group compared to the lithium disilicate glass ceramic group (Table 1).

Average mean and standard deviation of the recorded variables is presented in (Table 2).

Color change

There was significant difference between L2 and L3 in all groups except in the Feldspar ceramic treated with hydrogen peroxide group whereas L value was significantly increasing after bleaching in the three other groups (Table 3).

a values was significantly decreasing after hydrogen peroxide treatment in the stained lithium disilicate bleached with hydrogen peroxide, meanwhile it didn’t differ in the other groups. As for the b values, there was a significant increase in both Feldspar groups after sodium perborate and hydrogen peroxide treatment (Table 3).

Chroma values increased significantly in both feldspar ceramic groups while hue values increased significantly in both lithium disilicate groups (Table 3).

Regarding each bleaching agent and ceramic type, there was no significant difference between color changes ∆E002 values of all groups, even though lithium disilicate treated with sodium perborate group showed the highest ∆E002 (Table 4).

Surface roughness

There was significant difference in surface roughness between the phase of after staining and after bleaching in each group. Surface roughness increased significantly in each group after staining and after bleaching (Table 3). However, no significant differences were found between groups regarding surface roughness according to the bleaching agent and ceramic type (Table 4).

Residual color

All groups showed residual discoloration below 1.8 with a significant differences between all groups in this regard (Table 4), the Bonferroni test result revealed a significant difference only between lithium disilicate ceramic treated with sodium perborate group and feldspar ceramic treated with Hydrogen peroxide group as lithium disilicate ceramic treated with sodium perborate group retrieved original color better (Table 5).

Correlation between color and roughness changes

A positive correlation was found between color and roughness changes in the sodium perborate treated groups. As the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.53 which indicate a moderate positive correlation. Meanwhile, no correlations was found between the ∆E002 & Ra2 in the hydrogen peroxide treated groups.

Discussion

Dental porcelain remains relatively stable for long periods of time, it is an insoluble or slightly soluble material and does not react easily with most liquids and gases1. However, its resistance decreases significantly after functional loading and exposure to a moist oral environment23. Also, color changes have occurred in porcelain exposed to solutions such as coffee, tea, and yogurt24,25,26. and even water15. Several studies confirm color changes after the use of bleaching materials on resin and ceramic materials27,28. Therefore, this study was conducted to find a conservative solution to retrieve ceramic color instead of replacing the restoration.

Results showed L value increased both lithium disilicate ceramic regardless of the bleaching agent, while it only increased in the Feldspar ceramic treated with sodium perborate. Meanwhile, Chroma values increased significantly in both feldspar ceramic groups while hue values increased significantly in both lithium disilicate groups, this means that the color was more saturated in the feldspar ceramic group. But the lithium disilicate ceramic treated with sodium perborate group appeared brighter than the other group without any significant differences, as L value represents brightness, which means the group with the higher value (closer to 100) appears brighter or lighter. Brightness changes are more effective on color difference than Chroma or hue changes29.

The average values of residual color of all groups were below clinically acceptable threshold (< 1.8)14.this finding reject the null hypothesis and shows the ability of both bleaching agent on retrieving original color of the ceramic. Whereas the clinical acceptability is classified according to amount of color change: When ∆E00 is equal or less than 0.8, color change is considered clinically acceptable and indistinguishable by human eye. When ∆E00 is blow 1.8, it is considered clinically acceptable but can be observed by an experienced. When ∆E00 is greater than 1.8, it is considered clinically unacceptable14. Moreover, there was a significant difference between two groups regarding the residual color values, as lithium disilicate ceramic treated with sodium perborate group retrieved original color significantly better than the Feldspar ceramic treated with hydrogen peroxide. This can be attributed to the color stability of lithium disilicate and the short application time of hydrogen peroxide.

Roughness increased significantly after staining and bleaching in all groups with no difference between them, this can be explained by the cumulative effect of staining and bleaching on Specimens surfaces, as specimens were exposed to multi stained solutions that have low pH and acidic nature. And followed by application of bleaching agents that interact with ceramic’s metal ions, all of the previous partials cause chelation of metal ions from ceramic surface, which in turn led to an increase in surface roughness. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in roughness changes caused by tested bleaching agents, despite difference in power oxidation for the two agents. Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidant15, and it was applied in a high concentration, but for a short period. On the other hand, sodium perborate is a weaker oxidant15, but was applied for enough time to make it equivalent in effectiveness to hydrogen peroxide.

This results contraindicate with those of Ozdogan et al. 2019 study29, as it only revealed an increase in surface roughness of the feldspar ceramics after bleaching and didn’t notice any color change, this could be attributed to the different concentration of the hydrogen peroxide applied and the absence of another bleaching agent.

This study results disagree with Gasparik et al. 201930 study results which found that color change of ceramic materials (feldspar porcelain, lithium disilicate-based glass-ceramic, and hybrid porcelain) between after staining and bleaching was not perceptible30. This is due to the use of different staining and bleaching protocols, as they used only coffee as a staining solution, and a 10% carbamide peroxide as a bleaching material for shorter time periods.

Also, a discrepancy between Sağlam and Cengiz. 202131 results and the current study results, as they didn’t find any color differences after bleaching stained feldspar ceramics, this attributes to the different immersion protocol and bleaching agent concentration.

Meanwhile, these results agreed with those of Thaworanuntaet al. 201932 and Al-Angari et al., 202133 as they found a significant color change and an increase roughness of lithium disilicate-based glass ceramics after bleaching with 35% carbamide peroxide for an hour, which was soaked in coffee for 45 days32, and that specimens returned to their original color33.

There was a correlation between color changes and roughness after bleaching using sodium perborate, while no correlation was found after bleaching using hydrogen peroxide, this is because of the topography surface effect on optical properties of the material, and while sodium perborate dissolved pigments on ceramic surface. Hydrogen peroxide is a more powerful oxide that dissolved both silica and pigments15.

Unfortunately, and despite advantages of laboratory studies related to their ability to control various variables (ceramic type, bleach type, staining solutions), it is difficult to reproduce complex conditions of thermal, chemical, and mechanical changes which are found in the oral environment. Therefore, clinical studies are needed to confirm these findings. In addition, the presence of saliva in mouth as a moisturizing agent can effect optical properties of surface of restorative materials.

Conclusions

Hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate can induce color changes and increase surface roughness in stained feldspar and lithium disilicate porcelain specimens. As original color of stained feldspar and lithium disilicate porcelain can be recovered by 30% hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate, therefore they can be used to modify color of ceramic restorations discolored by dietary habits.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shen, C., Rawls, H. R. & Esquivel-Upshaw, J. F. Ceramic-based materials: phillips’ science of dental materials, thirteenth edition. Elsevier:202–232 (2022).

Sakaguchi, R., Ferracane, J. & Powers, J. Restorative materials: ceramics. Craig’s restorative dental materials, Fourteenth edition. Elsevier:209–225 (2019).

Shi, H. Y. et al. Overview of several typical ceramic materials for restorative dentistry. Biomed. Res. Int. 8451445. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8451445 (2022).

Skorulska, A., Piszko, P., Rybak, Z., Szymonowicz, M. & Dobrzynski, M. Review on polymer, ceramic and composite materials for CAD/CAM indirect restorations in dentistry-application, mechanical characteristics and comparison. Mater. (Basel). 14 (7), 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071592 (2021).

Ispas, A. et al. Comparative assessment of the functional parameters for metal-ceramic and all-ceramic teeth restorations in prosthetic dentistry: a literature review. Biology 11 (4), 556 (2022).

Zeng, K., Oden, A. & Rowcliffe, D. Flexure tests on dental ceramics. Int. J. Prosthodont. 9 (5), 434–439 (1996).

Shetty, R. et al. Resin-matrix ceramics – an overview. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 6 (11), 7414–7417 (2016).

Yılmaz, K., Gonuldas, F. & Ozturk, C. The effect of repeated firings on the color change of dental ceramics using different glazing methods. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 6 (6), 427–433. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2014.6.6.427 (2014).

Silva, E. A. et al. Impact of high-consumption beverages on the color, and surface roughness and microhardness of resin-matrix ceramics. Dent Med Probl. 62(2):299–307. (2025). https://doi.org/10.17219/dmp/171320. PMID: 40407142.

Sánchez-Salcedo, E. M., Amorós, A., Hernández, F. & Martínez, J. J. Physicochemical properties of white (Morus alba) and black (Morus nigra) mulberry leaves, a new food supplement. J. Food Nutr. Res. 5, 253–261 (2017).

Khasnabis, J., Rai, C. & Roy, A. Determination of tannin content by titrimetric method from different types of tea. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 7 (6), 238–241 (2015).

Benahmed, A. G. et al. A review on natural teeth whitening. J. Oral Biosci. 64 (1), 49–58 (2022).

Abdalkadeer, H. K. et al. Influence of the Coca-Cola drinks on the overall color of glazed or polished porcelain veneers fabricated from different materials and thicknesses: an in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 21 (1), 56–61 (2020).

Xu, B. T., Zhang, B., Kang, Y., Wang, Y. N. & Li, Q. Applicability of CIELAB/CIEDE2000 formula in visual color assessments of metal ceramic restorations. J. Dent. 40, e3–e9 (2012).

Soliman, F. M., Dawood, L. & Abo El-Farag, S. A. Effect of in-office bleaching techniques and topical fluoride application on color and surface roughness of two types of dental ceramics (in-vitro study). Egyptian Dent. J. 66, 1243–1251 (April, 2020).

Sharaf, K. & khadour, A. Metrology-mechanics: Chap. 4. (299–334) (Damascus University, Faculty Mechanical Electrical Engineering, 2014) .

Kukiattrakoon, B., Hengtrakool, C. & Kedjarune-Leggat, U. Effect of acidic agents on surface roughness of dental ceramics. Dent. Res. J. 8 (1), 6 (2011).

Plotino, G., Buono, L., Grande, N. M., Pameijer, C. H. & Somma, F. Nonvital tooth bleaching: a review of the literature and clinical procedures. J. Endod. 34 (4), 394–407 (2008).

Karaokutan, I. & Aykent, F. Effect of a home bleaching agent on the ion elution of different esthetic materials. J. Prosthodont. 29 (9), 805–813 (2020).

Joiner, A. The bleaching of teeth: a review of the literature. J. Dent. 34 (7), 412–419 (2006).

Vadher, R. et al. Basics of color in dentistry: A review. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 13 (9), 78–85 (2014).

Zimmerli, B., Jeger, F. & Lussi, A. Bleaching of nonvital teeth. Schweiz. Monatsschr Zahnmed. 120 (4), 306–313 (2010).

Zhang, Y., Sailer, I. & Lawn, B. R. Fatigue of dental ceramics. J. Dent. 41 (12), 1135–1147 (2013).

Sağlam, G. & Cengiz, S. The evaluation of the effect of coffee staining and 16% carbamide peroxide bleaching on the color change of chairside CAD/CAM ceramics. J. Dent. Mater. Technique. 10 (4) (2021).

Salah Eldine, D., Kamel, M. & Morsy, A. The color change of indirect zirconia containing restorative materials. Egypt. Dent. J. 67, 1701–1709 (2021).

Aldosari, L. I. et al. Surface roughness and color measurements of glazed or polished hybrid, feldspathic, and zirconia CAD/CAM restorative materials after hot and cold coffee immersion. BMC Oral Health. 21 (1), 422 (2021).

Dos Santos, D. M. et al. Effect of different acidic solutions on the optical behavior of lithium disilicate ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 118 (3), 430–436 (2017).

Kurt, M. & Bal, B. T. Effects of accelerated artificial aging on the translucency and color stability of monolithic ceramics with different surface treatments. J. Prosthet. Dent. 121 (4), 712 (2019).

Ozdogan, A., Duymus, Z. Y., Ozbayram, O. & Bilgic, R. Effect of different bleaching agents on the surface roughness and color stability of feldspathic porcelain. Brazilian Dent. Sci. 22 (2), 213–219 (2019).

Gasparik, C. et al. Effect of accelerated staining and bleaching on chairside CAD/CAM materials with high and low translucency. Dent. Mater. J. 38 (6), 987–993 (2019).

Sağlam, G. & Cengiz, S. The evaluation of the effect of coffee staining and 16% carbamide peroxide bleaching on the color change of chairside CAD/CAM ceramics. J. Dent. Mater. Techniques. 10 (4), 198–205 (2021).

Thaworanunta, S. et al. Exposure to coffee and bleaching altered surface treated lithium disilicate porcelain color and surface roughness. Mahidol Dent. J. 39 (3), 267–276 (2019).

Al-Angari, S. S., Eckert, G. J. & Sabrah, A. H. Color stability, roughness, and microhardness of enamel and composites submitted to staining/bleaching cycles. Saudi Dent. J. 33 (4), 215–221 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nour kaheel: conceptualization, collection and data analysis, writing the original draft. Issam Jamous: writing- review and editing, supervising, Jamila Bchara writing- data analysis, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaheel, N., Bchara, J. & Jamous, I. Effect of bleaching materials on optical properties and surface roughness of discolored dental ceramics. Sci Rep 15, 37436 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21258-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21258-1