Abstract

We report the use of microwave plasma for the production of hydrogen-enriched gas by converting a mixture of CO₂ and CH₄. A novel type of compact and simple in design, waveguide-based, atmospheric pressure plasma source is used. It doesn’t contain a discharge tube, but involve a swirling gas flow and operates without a catalyst. The influence of the input parameters on the conversion process parameters is investigated. It is found that the power of microwaves benefits the concentration of H2, but the gas flow rate is found to be detrimental to the H2 concentration. It is observed that the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio is another factor influencing the process parameters. The best results obtained of H2 concentration and conversion rate of CH4 are 33% and 46%, respectively, while in the terms of H2 production rate and the energy yield of H2 production are 118 g/h and 30 g/kWh, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is now widely believed that the era of global dependence on fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, oil) is coming to an end1,2,3,4. This is partly due to the depletion of fossil fuel reserves, the ever-increasing price of fossil fuels and the desire of countries to become independent of political pressure from countries still rich in these fuels. Secondly, there is growing concern about the state of the environment. Indeed, the intensive use of fossil fuels by industry has contributed to the increase of greenhouse gases level (mainly CO2 and CH4) in the Earth’s atmosphere leading to a global climate disruption. The search for alternative energy sources and methods to reduce greenhouse gas concentrations are therefore two of the greatest challenges facing the world today. The authorities in a number of countries believe that a viable and beneficial solution is to switch from fossil fuel-based energy to hydrogen-driven energy, using hydrogen as the energy carrier. The use of hydrogen as a carbon-free energy carrier would have a significant positive impact on environmental problems. For the above reasons, dry methane reforming has recently attracted considerable interest, as it consumes two major greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4) in order to simultaneously convert them, at the same time, into other valuable products (such as H2)5,6,7,8,9:

Such hydrogen can be considered more environmentally friendly if it is produced using methane from the biogas10,11,12,13 and carbon dioxide from carbon capture and utilisation (CCU)14,15,16,17 as feedstocks.

Among various methods, plasma-based technology is considered as one of the potential routes for the reforming of CO2 with CH4. And one plasma technology that has attracted considerable remark due to its prospective potential is the microwave plasma18,19,20,21.

Microwave plasma is generated by applying the energy of a high-frequency electromagnetic field (0.3–300 GHz) to a gas. As a result, light electrons collide with gas atoms and molecules, causing their ionisation, excitation and dissociation. This creates new active plasma constituents such as electrons, ions, excited state atoms and molecules and radicals are formed22,23. The presence of these highly reactive components in the microwave plasma means that catalysts do not need to be used for gas processing23,24. This eliminates the additional energy required to preheat the catalyst for activation, as well as the problems associated with catalyst lifetime and loss of activity. The other advantage of microwave plasma is that it can be operated without using internal electrodes. This in turn allows high purity plasma to be obtained that is free from impurities by electrode material and eliminates the need for maintenance or exchange of the electrode due to its erosion25,26,27,28. Microwave plasma achieves a high concentration and energy of electrons (typically higher than RF plasma) at a moderate low temperature of the gas29,30. The internal parameters of the microwave plasma such as e.g. concentration of electrons and temperature of the gas could be regulated within a wide scope by changing the input parameters like e.g. the microwave power and the gas flow rate21,31. Moreover, microwave plasma can be maintained at atmospheric pressure.

This has the advantage of eliminating the need for expensive vacuum equipment (e.g.: pumps, chambers, pressure gauges, seals, valves), leading to a less complicated plasma system and a decreased cost of generation of the plasma. Furthermore, due to the use of widely available, low cost commercial magnetrons (at 2.45 GHz) and waveguide components, the manufacturing cost of a microwave plasma system can be relatively low compared to other plasma sources32. It should also be mentioned that the efficiency of the microwave energy transfer from the electromagnetic field to the plasma can reach almost 100% in the case of a properly designed microwave plasma source with optimally selected operating parameters26,33. Another feature to be highlighted in the context of microwave plasma is that, since this type of plasma is generated by electricity, it ensures a faster response time e.g. in comparison with conventional hydrocarbon reforming technologies.

Experimental and theoretical studies on the conversion of CO2 and CH4 mixtures using microwave plasma have been carried out in a number of scientific centers. The results of these studies can be found, for example, in34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. This was also the subject of interest of the co-authors of the present article, who presented their research findings in the papers52,53,54. In48,50 tables comparing the characteristics of dry methane reforming driven by different types of plasmas (including microwave plasma) could be found. In54, the process parameters of the dry methane reforming are compared only for the use of microwave discharge plasmas. Mostly, all these studies were carried out with microwave plasma systems operated at atmospheric pressure and frequency of 2.45 GHz, but a 915 MHz based system was also used51,53,54. Usually, the microwave power was delivered to the plasma in a continuous mode, although in34,35 a pulsed mode of operation was used. In one case, a catalyst was also used39. In the vast majority of cases, as in our previous studies52,53,54, the plasma in a form of a flame or a column was sustained within a dielectric (mostly made of quartz) tube. The total input gas flow rate and microwave power did not exceed the 60 NL/min and 10 kW, respectively. The exceptions are the work of51, where the total input gas flow rate was up to 180 NL/min and the microwave power was up to 45 kW, and54, where the total flow rate of the input gas was up to 200 NL/min, but the microwave power did not exceed the 6.5 kW. Both works used a 915 MHz based plasma system.

In this paper, we report an atmospheric pressure microwave plasma-based method for the production of hydrogen-enriched gas from a mixture of two major greenhouse gases (CO2 + CH4). The novelty aspect of our present experimental investigations lays mainly in the type of the microwaves plasma source (MPS) used. This new MPS has been submitted to the Polish Patent Office as a “2.45 GHz microwave plasma block for gas conversion with metal inner insert” and it is inscribed on the list of Utility Model Protection Law of the Polish Patent Office under registration number of Ru.073465. The submitted manuscript is therefore the first to address the application of the aforementioned plasma source for gas processing. The new MPS is compact and simple in design, operates at the standard microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz and is based on a WR340 type rectangular waveguide. The lack of a dielectric discharge tube (often made of quartz) in which the plasma is generated and maintained distinguishes it from other atmospheric pressure plasma sources. This is a significant benefit as it prevents overheating and thermal damage to the discharge tube. These are the problems that were encountered in our previous works. At the same time the new MPS is designed to handle high swirl flow rates of the input gas (as much as several hundred NL/min) and to operate at microwave power levels of the order of a few kW without a catalyst. Thus, the key novelty of our present experimental investigations is the use, for hydrogen fuel production from CO2/CH4 mixture, of a relatively simple new MPS of an extended failure-free operating time, both of which make it attractive for practical applications in the gas processing.

In our study, the effect of the input parameters such as: the absorbed microwave power, the total input gas flow rate, and the flow rate ratio of CO2 and CH4 on the efficiency of hydrogen-rich gas production was experimentally investigated.

Methods

Plasma source

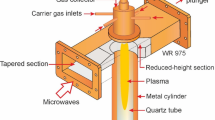

A schematic drawing of a new type of microwave plasma source, which we have used in the present work for the production of hydrogen by the conversion of a CO2 - CH4 mixture, is shown in Fig. 1. Its design, described below, is the subject to the Utility Model Protection Law of the Polish Patent Office (registration number: Ru.073465). It operates in gases at atmospheric pressure and at a microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz. It is based on a standard WR340 (WG9A, R26) rectangular waveguide with internal dimensions of 86.4 mm × 43.2 mm. The plasma source is therefore also fed by a rectangular waveguide of the same standard. Inside the plasma source there is a wedge-shaped metal section is placed (tapered section). Its height varies linearly over a distance equivalent to half of the length of the 2.45 GHz microwave (λg/2) within the WR340 waveguide. The wavelength λg in the waveguide for the microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz is equal to 173.4 mm. Thus, the tapered section acts as a reflectionless impedance transformer. At the end of the wedge a metal block is placed to form a reduced-height section. Its height is equal to the height of the end of the wedge and its length is equal to λg/2. The space between the waveguide top wall and the ridge of the section of reduced-height is closed by a cylindrically hollowed flat rectangular insert made of metal (aluminum). The width of the two sections and the metal insert is the same as the width of the waveguide, so that they completely fill the waveguide along its wider wall. The working gas is introduced through two opposite holes in the narrower walls of the waveguide and the metal insert in such a way as to create a swirling flow in the hollow cylindrical space of the metal insert. In this way, the metal insert ensures that the working gas is concentrated in the central area and prevents it from escaping from this area.

A rectangular dielectric (Teflon) partition, centrally located on the microwave feed side (waveguide side), is also mounted in the metal insert. It allows the microwaves to penetrate the plasma source. The swirl flow of a working gas protects the dielectric partition from overheating and contamination. When microwave power is applied and working gas is supplied, plasma is formed in the region between the cylindrical metal (brass) inner duct with tungsten tip and the cylinder gas outlet. The photo of the novel microwave plasma source described above is shown in Fig. 2.

Experimental set-up

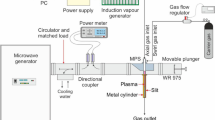

A sketch of the set-up for experimental investigations of hydrogen-rich gas production using a novel type of an atmospheric pressure MPS is shown in Fig. 3. It consists of a microwave power generator system, a microwave power measurement system, a tuning element, a plasma source, a gas supply and flow control system, a soot filter and a gas analysis system. The microwave power generator system consists of a high voltage power supply (Muegge MS6000D-113EE), a control unit (Muegge model MD2323D-110AA) and a magnetron head (Muegge MH6000S-210BF). The magnetron head is equipped with a water-loaded circulator to protect it from possible damage caused by the reflected microwave power. Such a microwave power generator system operating in continuous mode at a standard microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz provides a continuously variable microwave output power in the range from 0.6 kW to 6 kW. The microwave power from the microwave power generator system is transferred to the plasma source via a standard WR340 rectangular waveguide with internal dimensions of 109.22 mm × 54.61 mm operating in the fundamental TE10 mode. The microwave power measurement system consists of a calibrated bidirectional coupler, incident and reflected power sensors (Agilent E9301A) and a digital dual-channel power meter (Agilent E4419B). The directional coupler is used to sample the incident and reflected microwave power for direct measurement of their values by the power meter. The absorbed microwave power is then calculated by subtracting the reflected power from the incident power.

The microwave plasma source is preceded by a three stub-tuner. This tuning element is used to minimize the reflected power in the waveguide line thus matching the plasma source impedance to the impedance of the supplying waveguide. By using of it, it is possible to reduce the reflection coefficient of the microwave power to zero for any discharge conditions (e.g. microwave input power, gas flow rate). The working gases CO2 (purity ≥ 99.8% by volume) and CH4 (purity ≥ 99.5% by volume) from the pressurized gas tanks supplied by Air Liquide Polska are mixed into a gaseous mixture, and are fed in that form into the plasma source. The working gas flow rates are controlled by means of mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst EL-FLOW series). To capture the soot formed during methane conversion, the plasma source is equipped with a lab-made gas-soot separator of the centrifuge type. The outlet gas from the plasma source is sampled after leaving the gas-soot separator. The outlet gas samples are collected in Tedlar® bags and the composition of outlet gas is analyzed using a gas chromatograph (SRI Instruments 8610 C) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet 380) operating in the range of 1000–4000 cm−1. At least three analyses were performed on each outlet gas sample.

Parameters of the process

The following parameters were used to describe the efficiency of hydrogen-rich gas production in an atmospheric pressure microwave plasma conversion process of the CO2 + CH4 mixture: microwave power absorbed in the plasma (Pabs), total flow rate of the input gas (Qtot), specific energy input (SEI), gaseous plasma component’s volume concentration in the outlet gas (Cx), CO2 conversion rate (XCO2), CH4 conversion rate (XCH4), selectivity of H2 (SH2), selectivity of CO (SCO), hydrogen production rate (YH2), energy yield of hydrogen production (ηΗ2).

The microwave power absorbed in the plasma (Pabs) is calculated as the difference between the incident microwave power (Pinc) and the reflected microwave power (Pref).

The total flow rate of the input gas (Qtot) is defined as the sum of the CO2 flow rate (QCO2) and CH4 flow rate (QCH4):

The specific energy input (SEI) is determined by dividing the microwave power absorbed in the plasma (Pabs) by the total flow rate of the input gas (Qtot):

The gaseous plasma component’s volume concentration in the outlet gas (Cx) describes the content in percent of an individual constituent in the outlet gas. When it comes to H2 (CH2) it is defined in the following way:

where the QH2 is the outlet flow rate of H2 and Q(CO2+CO+CH4+C2H2+C2H4+C2H6) is the outlet flow rate of CO2 + CO + CH4 + C2H2 + C2H4 + C2H6.

The CO2 conversion rate (XCO2) is determined by the following:

where MCO2input is the number of input CO2 moles and MCO2output is the number of CO2 moles at the outlet.

The CH4 conversion rate (XCH4) is determined by the following:

where MCH4input is the number of input CH4 moles and MCH4output is the number of CH4 moles at the outlet.

According to reaction (1), the selectivity of H2 is described by the following relationship:

where QH2outlet is the flow rate of H2 at the outlet of the plasma generator, QCH4inlet is the CH4 input flow rate into the plasma generator, and QCH4outlet is the CH4 flow rate at the outlet of the plasma generator.

Selectivity of CO is determined by:

where QCOoutlet is the flow rate of CO at the outlet of the plasma generator, QCO2inlet is the CO2 input flow rate into the plasma generator, and QCO2outlet is the CO2 flow rate at the outlet of the plasma generator.

The hydrogen production rate (YH2) indicates the amount of hydrogen generated in grams (mH2) per unit of time (T), using one hour as the unit of measure:

The energy yield of hydrogen production (ηΗ2) reveals the quantity of hydrogen generated by absorbing 1000 Wh of microwave power:

Numerical modeling

In order to determine the chemical reaction mechanism responsible for our experimental results the numerical modeling was performed. The dry reforming of methane was modeled utilizing a Plug Flow Reactor (PFR) framework, employing the SGEE (Solving Gas Energy Equation) solver within the ANSYS Chemkin-Pro environment. The PFR framework represents an idealized one-dimensional reactor configuration that is utilized for continuous plug flow, wherein both radial diffusion and back mixing are neglected, thereby yielding a consistent flow velocity, gas concentration, temperature, and residence time in the direction orthogonal to the airflow. In this analysis, the PFR was characterized by an adiabatic wall boundary, a diameter of 14 mm and a length of 55 mm, reflecting the size of the high-temperature region observed in the experiment. Methane and carbon dioxide were introduced into the PFR reactor as a single stream. A set of reactions created by combining the complete GRI-Mech 3.0 mechanism55 and the soot formation model developed by Appel et al.56 was used to model the kinetics of chemical reactions.

Results

In accordance with the objective of the presented studies, the following section describes the experimental results on the parameters of the microwave plasma conversion process of the CO2 + CH4 mixture. The aim of the first part of the section is to present the results on the influence of the absorbed microwave power on the parameters of the plasma conversion of the CO2/CH4 mixture. In the second subsection the problem of the role of the total gas flow rate of the input gas is addressed. The third subsection focuses on the influence of the CO2 + CH4 flow rate ratio.

Influence of the absorbed microwave power

Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the effect of the absorbed microwave power levels (in the range of the 1.5–4.5 kW) on the gaseous plasma component’s volume concentration (Fig. 4), on the CO2 and CH4 conversion rate (Fig. 5), as well as, on the rate of H2 production and the energy yield of H2 production (Fig. 6). The obtained results presented refer to the total flow rate of the input gas of 50 NL/min and the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio of 1.

As shown in Fig. 4, the gas chromatography and FTiR spectrophotometer diagnosis of the composition of the output gas from the MPS revealed that the following gas by-products were detected: H2 (hydrogen), CH4 (methane), C2H2 (acetylene), CO (carbon monoxide) and CO2 (carbon dioxide). It is to be expected that the CH4 and CO2 registered in the outlet gas originate mainly from the unprocessed input gas components indicating their incomplete conversion. Small concentrations of higher hydrocarbons such as C2H4 (ethylene) and C2H6 (ethane) were also detected in the experiment, but their concentrations were less than 1% of the total volume concentration of the gaseous plasma components in the outlet gas. Carbon soot formation was also observed in the form of a soot deposit on the internal parts of the plasma source. The structures and morphologies of the carbon soot produced were not studied. No water content was detected or even observed in the output gas for any of the conditions that were investigated in our study. As the water content would be expected in the outlet gas, its absence in our experiment can be explained by water dissipation within the MPS or/and adsorption on solid carbon particles. However, it should be emphasized that the production of solid carbon and water was predicted in the chemical reactions related to the dry reforming of methane given in the works of36,43,46,47,48, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 4, the linear decrease in the volume concentrations of CO2 and CH4 in the outlet gas can be observed as the absorbed microwave power was increased. As the absorbed microwave power was increased from 1.5 kW to 4.5 kW, the volume concentration of CO2 decreased from 34.8 to 23.1%, and that of CH4 decreased from 36.9% to 18.8%. At the same time, a linear increase in the volume concentration of H2, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6 and CO was observed with each increase in the absorbed microwave power. Among the five gaseous components mentioned, hydrogen has the highest concentration in the output gas. The volume concentration of H2 in the outlet gas was 15% and 33%, for the microwave power absorbed of 1.5 kW and 4.5 kW, respectively. This means that, in the best case, the outlet gas leaves the plasma source enriched with 33% hydrogen.

In conclusion, firstly, the recorded changes in the concentrations of substrates (CH4 and CO2) and products (H2, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6 and CO) in the output gas proved that the atmospheric pressure microwave plasma, within the range of experimental parameters used, is capable of carrying out the desired CH4 and CO2 conversion reactions, and secondly, the decrease in the concentrations of substrates and the increase in the concentrations of products in the outlet gas confirmed the positive effect of the input microwave power on this process. It should be noted here, that, the similar effect of the power delivered to the plasma on the parameters of the conversion process of the CO2 and CH4 mixture was also an observation of other experimental studies using microwaves of the frequency of 2.45 GHz43, as well as, of the frequency of 915 MHz51.

As the absorbed microwave power increases in (while keeping the total input gas flow rate constant) due to the increase in SEI, the plasma parameters are enhanced due to the increase in temperature of the gas and concentration of free electrons. This favors a higher collision rate between plasma components, which enhances chemical interactions and leads to an increased conversion of reaction substrates into alternative chemical products, such as H2 in our case. This can be clearly seen in Fig. 4, which also shows the H2 concentration in the outlet gas and in Fig. 5 which shows the CH4 conversion rate as a function of the microwave power absorbed in the plasma. It can be seen that, an increase of the microwave power absorbed resulted in an increase of the volume concentration of H2 in the output gas, as well as, the CH4 conversion rate. The CH4 conversion rate increased from 11.5% to 46%, respectively, when the absorbed microwave power increased from 1.5 kW (SEI = 1.8 kJ/L) to 4.5 kW (SEI = 5.4 kJ/L). As it can be further seen from Fig. 5, a similar effect of absorbed microwave power on the CH4 conversion rate is also observed in the case of the CO2 conversion rate. The CO2 conversion rate increases with each subsequent increase in the microwave power delivered to the plasma. In this case, the CO2 conversion rate increased from 16.8% to 33.5% as the absorbed microwave power increased from 1.5 kW (SEI = 1.8 kJ/L) to 4.5 kW (SEI = 5.4 kJ/L).

Regarding the results presented in Fig. 4 one could note that an increase in the absorbed microwave power from 1.5 kW to 4.5 kW leads to about 10% decrease in CO2, while CO increases by less than 5%. As can be seen in Fig. 5, across the absorbed microwave power range used, CO2 conversion ranges from about 17% to 33%. In conjunction with the CO concentration shown in Fig. 4, this means that only one-third of the reacted CO2 is converted to CO. The remainder is a source of carbon and oxygen, which reacts with hydrogen. The resulting water is not detected by us in the gaseous products but condenses and mixes with the soot that accumulates in the separator.

Considering the selectivity of the two main products in the outlet gas, namely H2 and CO, our research to date has shown that, within the applied absorbed microwave power range of 1.5–4.5 kW, the selectivity of both decreases with an increase in the absorbed microwave power. The effect of this variation with the microwave power absorbed in the plasma is more significant in the case of H2 selectivity than in the case of CO selectivity.

Following the Eqs. 10 and 11, Fig. 6 shows the role of the microwave power absorbed in the plasma on the rate of H2 production and the energy yield of H2 production. As illustrated in the figure, increasing the absorbed microwave power resulted in a linear increase in the H2 production rate, as in the case of the volume concentration of H2 in the outlet gas and the CH4 conversion rate. The H2 production rate increased by about 2.6 times (from 44.6 to 117.5 g/h), as the absorbed microwave power increased from 1.5 kW to 4.5 kW. However, while increasing the microwave power absorbed favours the volume concentration of H2 in the output gas (see Fig. 4), the CH4 conversion rate (Fig. 5) and the H2 production rate (Fig. 6), it has a negative influence on the H2 production’s energy yield. As can be seen in Fig. 6, an increase in the microwave power absorbed in the plasma (at the same time as an increase in the SEI) resulted in a decrease in the H2 production’s energy yield. For the microwave power absorbed of 1.5 kW, the energy yield of H2 production was about 30 g/kWh, while for the microwave power absorbed of 4.5 kW, the energy yield of H2 production was equal to about 26 g/kWh.

According to the Eq. 11, the H2 production’s energy yield is calculated by dividing the H2 production rate by the microwave power absorbed in the plasma. Thus, the decrease in the H2 production’s energy yield with the increase in the microwave power absorbed indicates that the increase in the microwave power absorbed surpasses the increase in the H2 production rate. This means that less than all of the microwave power absorbed within the plasma is used to drive the plasma reactions (it is also used, for example, to heat the gas), resulting in a lower H2 production’s energy yield.

Influence of the total flow rate of the input gas

The effect of the total input gas flow rate on the volume concentration of the gaseous plasma components in the outlet gas, on the conversion rate of CO2 and CH4 and on the rate of H2 production and H2 production’s energy yield is shown in Figs. 7, 8 and 9, respectively. For the results presented in the above figures the measurements were carried out at the CO2 to CH4 flow rate ratio of 1, the microwave power absorbed in the plasma of 3.5 kW and the total flow rate of the input gas between 50 and 100 NL/min. The unfavourable relationship between the efficiency parameters of the CO2 + CH4 mixture conversion and the total flow rate of the input gas can already be seen in the first figure, namely Fig. 7, which shows the dependence of the gaseous plasma component’s volume concentration in the output gas on the total input gas flow rate. As it can be seen, increasing the total input gas flow rate resulted in an increase in the amount of input gases (CO2 and CH4) and a decrease in the amount of the H2, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6 and CO in the outlet gas. Thus, the increase in the flow rate of the CO2/CH4 mixture is coupled with a decrease in the rate of conversion of CO2, as well as, CH4, resulting in an increased amount of unutilized feedstock in the outlet gas. As shown in Fig. 8, both the CO2 conversion rate, as well as the CH4 conversion rate, at constant absorbed microwave power decrease with increasing the total input gas flow rate. The CH4 conversion rate decreased from about 36 to about 10%, while the CO2 conversion rate decreased from about 27 to about 16%, as the total flow rate of the input gas increased from 50 to 100 NL/min. At the same time, the volume concentration of H2 in the output gas decreased from about 28 to about 17% and the output volume concentration of CO decreased from about 3 to about 2.2% with an increase in the total flow rate of the input gas in the same range.

Based on the results of our experimental studies, it was also found that, within the scope of the above working conditions, both the H2 selectivity and the CO selectivity increase with increasing the total flow rate of the input gas. However, the increasing rate of the H2 selectivity was observed to be more noticeable than the increasing rate of the CO selectivity.

Figure 9, which shows the dependence of the H2 production rate and the H2 production energy yield on the total input gas flow rate, reveals only slight changes in the values of the two parameters mentioned. In contrast to the results of Fig. 6 presenting the role of the microwave power absorbed in the plasma on the production rate of H2 and the energy yield of H2 production, in this case there is no significant increase or decrease in their values as the total flow rate of the input increases. Over the range of the total input gas flow rate used the average value of the H2 production rate is equal to 98 g/h, while the average value H2 production’s energy yield is 28 g/kWh.

In conclusion, the results of our experimental studies on the role of the total flow rate of the input gas on the plasma conversion parameters of the CO2/CH4 mixture showed that the best process performance was obtained for low input flow rates of the CO2/CH4 mixture. This is due to the fact that the residence time of the substrates in the microwave plasma region is longer in this case compared to the case where higher input gas flow rates are used. This influence of the total flow rate of the input gas on the microwave plasma conversion parameters of the CO2/CH4 mixture was also observed in the experimental investigations of other researchers43,50. The longer time of residence of the feed gaseous mixture within the plasma zone means that CO2 and CH4 are more likely to be converted to alternative chemicals by collisions with electrons and chemically reactive species. Secondarily, due to Eq. 4, a lower total flow rate of the input gas at a fixed absorbed microwave power results in a higher value of the SEI which promotes an increased conversion rates of the feed gas constituents. Conversely, to achieve higher CO2 and CH4 conversion parameters of the CO2 CH4 mixture at a high total flow rate of the input gas (and low time of residence within the microwave plasma zone) a plasma that is more powerful is required.

Influence of the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio

Keeping the microwave power absorbed in the plasma (3.5 kW) and the total flow rate of the input gas (50 NL/min) fixed, i.e. at the constant SEI of 4.2 kJ/L, the role of the CO2 to CH4 flow rate ratio on the parameters of the microwave plasma conversion process of the CO2 and CH4 mixture was evaluated. The following CO2/CH4 flow rate ratios were tested: 60/40, 50/50, 40/60. The corresponding process parameters, such as volume concentration of H2 in the outlet gas, CO2 conversion rate, CH4 conversion rate, H2 production rate and energy yield of H2 production, are listed in Table 1. Based on the results presented in the table, it can be seen that the highest H2 volume concentration (equal to 28.7%) was recorded for the highest proportion of CH4 (at the same time, for the poorest content of CO2) in the entering mixture of the gas. Conversely, the lowest H2 volume concentration (equal to 24.2%) was obtained at the lowest CH4 content (at the same time, in the case of the highest CO2 content) in the entering mixture of the gas. In general, Table 1 shows the tendency for the volume concentration of H2 in the outlet gas to increase as the input mixture of the gas contains more CH4. However, as it can be seen, both the CO2 conversion rate as well as the CH4 conversion rate follows a different tendency than the H2 volume concentration in the outlet gas. The CO2 and CH4 conversion rate was observed to decrease when the amount of CH4 in the total input gas flow rate increases, and thus when the amount of CO2 flow rate decreases. Increasing the CH4 flow rate from 20 NL/min to 30 NL/min (at the same time decreasing the CO2 flow rate from 30 NL/min to 20 NL/min) causes a decrease in CO2 conversion rate from 41.8% to 15%, and a decrease in CH4 conversion rate from 43.5% to 24.8%. The same correlation between the CO2 and CH4 conversion rate and the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio was also observed in the work of57 regarding the CH4 reforming with CO2 using a nanosecond pulsed dielectric barrier discharge plasma. According to Eqs. (10) and (11), the H2 production rate and energy yield of H2 production increase with the increase of H2 volume concentration in the outlet gas, i.e. also with the increase of the percentage of CH4 in the input gaseous mixture. Thus, as it can be seen from Table 1 the best results in terms of the H2 production rate and energy yield of H2 production were obtained at the CO2/CH4 input flow rate ratio of 40/60. In this case the H2 production rate was equal to 104.7 g/h while the H2 production energy yield was equal to 29.9 g/kWh.

In summary, it is worth noting that, as the results of our investigations show, the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio is another factor that determines the efficiency of conversion of the CO2 + CH4 mixture in the 2.45 GHz microwave plasma at atmospheric pressure. It has been demonstrated that the values of the process parameters tend to change with a change in the proportions of CO2 and CH4 in the entering gaseous mixture, even though the other two input parameters, namely the microwave power absorbed and flow rate of the gas, are kept constant.

Chemical reaction mechanism

Modeling has shown that methane decomposition occurs according to the Kassel mechanism58, whereby primary ethane is synthesized via the dehydrogenation of methane. This results in the formation of methyl radicals (CH3), which then recombine. A series of subsequent dehydrogenation reactions lead to the production of hydrogen, ethylene, and acetylene. Ultimately, carbon and soot are formed. The role of carbon dioxide in the methane reforming process is to generate hydroxyl radicals:

These radicals participate in many reactions, particularly in the oxidation of soot59. Reaction (12) is also the main path of the decomposition of CO2 and the production of CO.

Summary and conclusions

In this work, we investigated the performance of a novel type of microwave plasma source as a device for efficient production of hydrogen-enriched gas by converting a mixture of CO2 and CH4. The new MPS has a simple and compact design using the standard rectangular WR-340 waveguide and operates at the standard microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz at atmospheric pressure without the use of a catalyst. In contrast to the microwave plasma sources previously used by us and others, the present source does not use a dielectric discharge tube, although it also uses a swirl type of input gas flow. The CO2 CH4 mixture conversion investigations were performed with varying process input parameters. Thus, the effect of the absorbed microwave power (from 1.5 kW to 4.5 kW), the total flow rate of the input gas (from 50 to 100 NL/min) and the CO2 to CH4 flow rate ratio (60/40, 50/50, 40/60) was studied. Under the above operating conditions, the novel plasma source exhibited stable, reproducible operation without intensive soot production. The experimental investigations focused mainly on the gas chromatographic analysis of the composition of the hydrogen-enriched outlet gas. On this basis, basic process parameters, such as the gaseous plasma component’s volume concentration, the volume concentration of H2, the conversion rate of CH4, the production rate of H2, and the energy yield of H2 production were determined. As a result, the microwave power absorbed in the plasma was determined to be favourable for the volume concentration of H2 by increasing the rate of conversion of CH4. However, the total flow rate of the input gas was found to be detrimental to the volume concentration of H2 in the outlet gas by decreasing the residence time of the reactants in the microwave plasma region. Moreover, the CO2/CH4 flow rate ratio was found to be another factor influencing the process parameters. The recorded results obtained of the volume concentration of H2 and conversion rate of CH4 were 33% and 46%, respectively, while in the terms of H2 production rate and the energy yield of H2 production were 118 g/h and 30 g/kWh, respectively. In fact, microwave plasma systems with higher CH4 conversion rates of, e.g. 84.9%40 and 96.4%45, can be found in the literature. However, these are usually cases with small input gas flow rates and microwave powers, which in the cited works were respectively 2 NL/min and 0.7 kW and 10 NL/min and 2 kW. On the other hand, the results obtained by us, can be compared, for example, to the work48, where the CH4 conversion rate was 42% at the gas flow rate of 60 L/min (flow rate ratio of CO2 to CH4: 50/50) and microwave power absorbed of 6 kW (SEI = 6 KJ/L).

In summary, this work showed the potential of using the novel MPS for hydrogen enriched gas production. Although some of the results obtained are promising, further investigations are need. First of all, in order to fully explore the application of the new MPS for dry methane reforming, further knowledge of the properties of the generated plasma is required. Therefore, the aim of our future studies is to perform optical emission spectroscopy to evaluate the effect of the input parameters on the internal parameters of the generated plasma, such as the vibrational and rotational temperature of the plasma species. Measures will also be taken to improve the parameters of the CO2/CH4 mixture conversion. This will be done by reconfiguring the way the input gases are fed into the MPS.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zainal, B. S. et al. Recent advancement and assessment of green hydrogen production technologies. Renew. Sust Energ. Rev. 189, 113941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113941 (2024).

Kamran, M. & Turzyński, M. Exploring hydrogen energy systems: A comprehensive review of technologies, applications, prevailing trends, and associated challenges. J. Energy Storage. 96, 112601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112601 (2024).

Chelvam, K., Hanafiah, M. M., Woon, K. S. & Ali, K. A. A review on the environmental performance of various hydrogen production technologies: an approach towards hydrogen economy. Energy Rep. 11, 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.11.060 (2024).

Wei, S., Sacchi, R., Tukker, A., Suh, S. & Steubing, B. Future environmental impacts of global hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2157–2172. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EE03875K (2024).

Yusuf, M. et al. Syngas production from greenhouse gases using Ni–W bimetallic catalyst via dry methane reforming: effect of W addition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 46, 27044–27061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.05.186 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Recent advances during CH4 dry reforming for syngas production: A mini review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 46, 5852–5874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.10.240 (2021).

Alipour, Z., Borugadda, V. B., Wang, H. & Dalai, A. K. Syngas production through dry reforming: A review on catalysts and their materials, preparation methods and reactor type. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.139416 (2023).

Awad, M. M. et al. Recent developments and current trends on catalytic dry reforming of methane: hydrogen production, thermodynamics analysis, techno feasibility, and machine learning. Energy. Conv. Manag. 304, 118252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118252 (2024).

Pham, T. T. et al. N. Microwave-assisted dry reforming of methane for syngas production: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 18, 1987–2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01055-0 (2020).

Swinbourn, R., Li, C. & Wang, F. A comprehensive review on biomethane production from biogas separation and its techno-economic assessments. ChemSusChem 17, e202400779. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202400779 (2024).

Bakkaloglu, S. & Hawkes, A. A comparative study of biogas and biomethane with natural gas and hydrogen alternatives. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 1482–1496. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EE02516K (2024).

Francisco Lópe, A., Lago Rodríguez, T., Faraji Abdolmaleki, S., Galera Martínez, M. & Bugallo, B. From biogas to biomethane: an in-depth review of upgrading technologies that enhance sustainability and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Appl. Sci. 14, 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14062342 (2024).

Silva, J., Gonçalves, J. C., Rocha, C., Vilaça, J. & Madeira, L. M. Biomethane production from biogas obtained in wastewater treatment plants: process optimization and economic analysis. Renew. Energy. 220, 119469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.119469 (2024).

Schakel, W., Oreggioni, G., Singh, B., Strømman, A. & Ramírez, A. Assessing the techno-environmental performance of CO2 utilization via dry reforming of methane for the production of dimethyl ether. Journal CO2 Utilization. 16, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2016.06.005 (2016).

Sun, S. et al. Upgrading CO2 from simulated power plant flue gas via integrated CO2 capture and dry reforming of methane using Ni-CaO. Sep. Purif. Technol. 308, 122956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122956 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Integrated CO2 capture and utilisation: A promising step contributing to carbon neutrality. Carbon Capture Science Technol. 7, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccst.2023.100116 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Techno-economic analysis of integrated carbon capture and dry reforming of methane. Energy 316, 134516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.134516 (2025).

Vadikkeettil, Y. et al. Plasma assisted decomposition and reforming of greenhouse gases: A review of current status and emerging trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 161, 112343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112343 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Plasma-assisted reforming of methane. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203221. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202203221 (2022).

Wang, K., Ren, X., Yin, G., Hu, E. & Zhang, H. Recent advances in plasma-based methane reforming for syngas production. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustainable Chem. 50, 100981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2024.100981 (2024).

Baig, S. & Sajjadi, B. Non-thermal plasma enhanced catalytic conversion of methane into value added chemicals and fuels. J. Energy Chem. 97, 265–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2024.05.024 (2024).

Whitehead, J. C. Plasma–catalysis: the known knowns, the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 243001. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/49/24/243001 (2016).

Sekiguchi, H. & Mori, Y. Steam plasma reforming using microwave discharge. Thin Solid Films. 435, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6090(03)00379-1 (2003).

Chu, F. et al. Catalyst-free oxidation reactions in a microwave plasma torch-based ion/molecular reactor: an approach for predicting the atmospheric oxidation of pollutants. Anal. Chem. 95, 2004–2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c04469 (2023).

Scapinello, M., Delikonstantis, E. & Stefanidis, G. D. The panorama of plasma-assisted non-oxidativemethane reforming. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process. Intensif. 117, 120–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2017.03.024 (2017).

Conrads, H. & Schmidt, M. Plasma generation and plasma sources. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 9, 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/9/4/301 (2000).

De La Fuente, J. F., Kiss, A. A., Radoiu, M. T. & Stefanidis, G. D. Microwave plasma emerging technologies for chemical processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 92, 2495–2505. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.5205 (2017).

Tendero, C., Tixier, C., Tristant, P., Desmaison, J. & Leprince, P. Atmospheric pressure plasmas: a review. Spectrochim Acta Part. B Spectrosc. 61, 2–30. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/9/4/301 (2006).

Moisan, M. & Wertheimer, M. R. Comparison of microwave and r.f. plasmas: fundamentals and applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 59, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/0257-8972(93)90047-R (1993).

Won, I. H. et al. Comparative study between atmospheric microwave and low-frequency plasmas: production efficiency of reactive species and their effectiveness. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 53, 05FR02. https://doi.org/10.7567/JJAP.53.05FR02 (2014).

Wnukowski, M., Van De Steeg, A. W., Hrycak, B., Jasiński, M. & Van Rooij, G. J. Influence of hydrogen addition on methane coupling in a moderate pressure microwave plasma. Fuel 288, 119674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119674 (2021).

Van Rooij, G. J. et al. C. M. Taming microwave plasma to beat thermodynamics in CO2 dissociation. Faraday Discuss. 18, 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5FD00045A (2015).

Ferreira, C. M. & Moisan, M. Microwave Discharges: Fundamentals and Applications (Plenum, 1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1130-8

Zhang, J-Q., Yang, Y-J., Zhang, J-S. & Liu, Q. Study on the conversion of CH4 and CO2 using a pulsed microwave plasma under atmospheric pressure. Acta Chim. Sin. 60, 1973–1980 (2002). https://sioc-journal.cn/Jwk_hxxb/EN/Y2002/V60/I11/1973

Zhang, J-Q., Zhang, J-S., Yang, Y-J. & Liu, Q. Oxidative coupling and reforming of methane with carbon dioxide using a pulsed microwave plasma under atmospheric pressure. Energy Fuels. 17, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef020069n (2003).

Khiabani, N. H., Yaghmaee, M. S., Sarani, A. & Shokri, B. Synthesis-gas production from CH4-CO2-Ar via microwave plasma torch. Adv. Stud. Theor. Phys. 6, 1273–1287 (2012).

Chaiya, E., Khongkrapan, P. & Tippayawong, N. Use of non-thermal microwave plasma for syngas production from dry reforming of compressed biomethane. Int J. Appl. Eng Res. 9, 6835–6842 (2014).

Chun, S. M., Hong, Y. C. & Choi, D. H. Reforming of methane to syngas in a microwave plasma torch at atmospheric pressure. Journal CO2 Utilization. 19, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2017.03.016 (2017).

Chun, S. M., Shin, D. H., Ma, S. H., Yang, G. W. & Hong, Y. C. CO2 microwave plasma—catalytic reactor for efficient reforming of methane to syngas. Catalysts 9, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9030292 (2019).

Alawi, N. M., Barifcani, A. & Abid, H. R. Optimisation of CH4 and CO2 conversion and selectivity of H2 and CO for the dry reforming of methane by a microwave plasma technique using a Box–Behnken design. Asia-Pac J. Chem. Eng. 13, e2254. https://doi.org/10.1002/apj.2254 (2018).

Alawi, N. M., Pham, G. H., Barifcani, A., Nguyen, M. H. & Liu, S. Syngas formation by dry and steam reforming of methane using microwave plasma technology. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 579. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/579/1/012022 (2019).

Alawi, N. M., Pham, G. H. & Barifcani, A. Microwave plasma dry reforming of methane at high CO2/CH4 feed ratio. Int. J. Chem. Mol. Eng. 13, 156–160 (2019).

Alawi, N. M. et al. Comparative study on the performance of microwave-assisted plasma DRM in nitrogen and argon atmospheres at a low microwave power. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 85, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2020.01.032 (2020).

Alawi, N. M., Nguyen, H. M. & Barifcani, A. Optimization of microwave power, CO2/CH4 ratio and total feed flow rate for the plasma dry reforming of methane plasma dry reforming of methane. Iraqi J. Oil Gas Res. 1, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.55699/ijogr.2021.0101.1003 (2021).

Sun, H., Lee, J. & Bak, M. S. Experiments and modeling of atmospheric pressure microwave plasma reforming of a methane-carbon dioxide mixture. Journal CO2 Utilization. 46, 101464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101464 (2021).

Kelly, S. et al. Microwave plasma-based dry reforming of methane: reaction performance and carbon formation. Journal CO2 Utilization. 75, 102564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2023.102564 (2023).

Biondo, O. et al. Avoiding solid carbon deposition in plasma-based dry reforming of methane. Green Chem. 25, 10485–10497. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3gc03595f (2023).

Cho, C. H. et al. Dry reforming process using microwave plasma generator with high carbon dioxide conversion efficiency for syngas production. Fuel 361, 130707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130707 (2024).

Zhang, X., Kobayashi, N. & Itaya, Y. Optical analysis of dry reforming of methane in microwave-induced plasma at atmospheric pressure. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 57, 2401003. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219592.2024.2401003 (2024).

Zhang, X., Kobayashi, N., Suami, A. & Itaya, Y. Reforming of methane and carbon dioxide to C2 hydrocarbons in microwave plasma at atmosphere pressure. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 57, 2387919. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219592.2024.2387919 (2024).

Akande, O., Lee, B., Okolie, J. & Museba, H. N. Hydrogen-rich syngas generation through microwave plasma reforming of greenhouse gases. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 48, 34649–34658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.05.262 (2023).

Jasiński, M., Czylkowski, D., Hrycak, B., Dors, M. & Mizeraczyk, J. Atmospheric pressure microwave plasma source for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 38, 11473–11483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.05.105 (2013).

Hrycak, B., Czylkowski, D., Jasiński, M., Dors, M. & Mizeraczyk, J. Hydrogen production via synthetic biogas reforming in atmospheric-pressure microwave (915 MHz) plasma at high gas-flow output. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 39, 695–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-019-09962-z (2019).

Czylkowski, D., Hrycak, B., Miotk, R., Dors, M. & Jasiński, M. Microwave plasma-assisted hydrogen production via conversion of CO2–CH4 mixture. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 78, 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.06.313 (2024).

Smith, G. P. et al. GRI-Mech 3.0. http://www.me.berkeley.edu/gri_mech/

Appel, J., Bockhorn, H. & Frenklach, M. Kinetic modeling of soot formation with detailed chemistry and physics: laminar premixed flames of C2 hydrocarbons. Combust. Flame. 121, 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-2180(99)00135-2 (2000).

Mei, D. et al. CH4 reforming with CO2 using a nanosecond pulsed dielectric barrier discharge plasma. Journal CO2 Utilization. 62, 102073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102073 (2022).

Kassel, L. The thermal decomposition of methane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 54, 3949–3961. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01349a019 (1932).

Neoh, K. G., Howard, J. B. & Sarofim, A. F. Soot oxidation in flames. In Particulate Carbon (eds Siegla, D. C. & Smith, G. W.) (Springer, 1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-6137-5_9.

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by Institute of Fluid Flow Machinery, Polish Academy of Sciences under programme IMP PAN O3Z1T1.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors made substantial contributions to the experimental investigations as well as to the preparing of the submitted manuscript. All of them have approved the submitted version of the manuscript. The particular contribution of the authors was as follows: Dariusz Czylkowski: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bartosz Hrycak: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Robert Miotk: Investigation, Validation. Mirosław Dors: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mariusz Jasiński: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Czylkowski, D., Hrycak, B., Miotk, R. et al. Hydrogen fuel production from CO2/CH4 mixture using a novel type of an atmospheric pressure microwave (2.45 GHz) plasma source. Sci Rep 15, 37426 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21309-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21309-7