Abstract

Regulation of brain glutamate is closely related to brain energy metabolism. Changes in both central glutamatergic function and peripheral energy metabolism have been implicated in psychosis risk, onset and long-term illness, but there is a lack of empirical evidence to link these processes. We investigated the relationships between glutamate and N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA, a potential marker of neuronal metabolic integrity) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), measured using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS), and peripheral markers of energy metabolism (mitochondrial complex I–V content, pyruvate and lactate) in individuals either at clinical high risk for psychosis or in the first episode of psychosis (N = 36) and healthy controls (N = 20). ACC Glx (glutamate + glutamine) levels were positively related with principal components relating to mitochondrial complex content, and this relationship did not differ between groups. These findings are consistent with the importance of mitochondrial ATP generation in regulating glutamatergic neurotransmission. While we did not find evidence that this relationship is disrupted in clinical high risk or first episode psychosis, further work is required to understand the mechanisms linking glutamate and energy metabolism in psychosis, including studies in larger cohorts, later stages of illness or in individuals with greater illness burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The psychosis clinical high risk (CHR) state is defined as an early disease stage prior to the onset of overt psychosis and is characterised by sub-threshold psychotic or non-specific psychiatric symptoms1. Individuals meeting CHR criteria have a 25% probability of transitioning to first episode psychosis (FEP) within 3 years, and a 35% probability within 10 years2. Understanding the active biological mechanisms at the early stages of psychosis is crucial for elucidating the pathophysiology underlying psychosis risk and onset, and for identifying potential targets for early intervention.

Recent reviews have highlighted the potential importance of the interplay between regulation of brain glutamate, mitochondrial dysfunction and energy metabolism in psychosis pathophysiology and onset3,4,5. Glutamatergic neurotransmission has been extensively associated with schizophrenia pathophysiology6,7. Maintaining ion gradients to support glutamatergic signalling and action potentials is the most energy-intensive process in the brain, consuming the majority of ATP produced via cortical glucose metabolism and accounting for an estimated 75–80% of total glucose use8,9,10. In addition to the energy requirements of glutamate homeostasis through the glutamate-glutamine cycle11,12, high concentrations of glutamate can inhibit mitochondrial complexes13,14,15 thus disrupting ATP production which may increase neuronal vulnerability to excitotoxicity16. In response, lactate and pyruvate levels may rise, serving as alternative energy substrates and neuroprotective factors by sustaining ATP production and buffering against metabolic stress17,18.

It has been proposed that during the early stages of psychosis, genetic and environmental risks converge to impair ATP production from glucose through oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, which may progress to compensatory increases in aerobic glycolysis and lactate formation at later illness stages4,5,19. However, most of the empirical evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction and disrupted energy metabolism in psychosis is derived from studies in chronic schizophrenia, (including postmortem), with relatively little in vivo investigation of the active mechanisms at the early stages of psychosis.

Glutamate can be measured in vivo using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). 1H-MRS meta-analyses have shown that compared to healthy volunteers, individuals with psychosis-related conditions, including schizophrenia, show an overall reduction in glutamate in the medial frontal cortex (mFC), including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)20,21,22. However, mFC/ACC glutamate levels may be increased at earlier illness stages, including in CHR individuals23 or FEP20,22. Moreover, psychosis is associated with greater variability in MFC glutamate, and this is more pronounced in younger individuals21. This may suggest greater disturbances in energy-expensive glutamate regulatory mechanisms at earlier illness stages.

1H-MRS also provides measurement of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), which is primarily synthesised in neuronal mitochondria24 and may provide a marker of neuronal metabolic integrity25,26 and mitochondrial energy output27. NAA levels in the frontal lobe are reduced in CHR28,29, FEP and chronic schizophrenia30. Together, these studies therefore indicate increased and more variable levels of MFC glutamate and decreased NAA, which may indicate impaired neuronal mitochondrial activity, during the clinical high risk and early stages of psychosis.

In early psychosis, elevations in peripheral markers of mitochondrial dysfunction are associated with greater symptom severity, poorer functioning and neurocognitive abilities31. Mitochondrial complex I activity may be elevated32 and positively correlated with positive and cognitive symptom severity33. In CHR individuals, while mitochondrial complex content does not differ compared to in healthy controls, complex III content appears negatively associated with prodromal negative and total symptom severity scores, and complex V content positively correlated with disorganisation severity scores19,34. Although brain lactate has not yet been investigated in CHR or FEP individuals, analysis of peripheral lactate and pyruvate suggests no change19 or decreases during the CHR stage35,36 but increases during FEP37. However, the relationships between brain glutamate and NAA with peripheral markers of energy metabolism have not yet been investigated.

In this study we tested the hypothesis that in CHR and FEP individuals compared to healthy controls, brain glutamate, measured using 1H-MRS, would be negatively associated with peripheral mitochondrial complex content and positively associated with lactate and pyruvate levels; and that NAA, as a marker of metabolic integrity, would show the opposite relationships. In exploratory analyses we tested for associations between these markers, symptom severity and cognitive performance.

Methods

Regulatory approvals

The study was performed in collaboration with Clinical and Translational Sciences CaTS BioBank under a repository protocol that allowed a re-analysis of previously acquired data approved by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board and now approved under Clinical and Translational Sciences (CaTS) BioBank by the Research Ethics Board (REB) of the Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et de Services Sociaux (CIUSSS) de l’Ouest-de-l’Île-de-Montréal—Mental Health and Neuroscience subcommittee for secondary analyses.

Participants included in the study were subset of a larger dataset recruited from July 20, 2011, to March 12, 2019 (Ontario, Canada). The study was performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, regulatory requirements, and the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a full explanation of study procedures. All CHR and FEP individuals had capacity to provide informed consent, as assessed by MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT).

The dataset reported here partially overlaps with previously published cohorts, including 1 H-MRS ACC38, mitochondrial complex analyses19 and C4A expression39. The analytic sample comprised 56 participants: 26 at CHR, 10 with FEP, and 20 healthy controls (HCs). HCs included in this study did not meet the diagnostic criteria for cannabis use disorder38.

To maximise statistical power and availability of both 1H-MRS and peripheral energy measures, CHR and FEP participants were combined into a single CHR + FEP group. Participants in the CHR + FEP and HC groups were then matched using propensity score matching (via the MatchIt package in R), based on age and sex.

Participants and clinical assessments

CHR participants met the diagnostic criteria for prodromal risk syndrome which was assessed using the criteria of prodromal syndromes (COPS)40. CHR participants were excluded if they currently met the criteria for any Axis I disorder, assessed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I)41. The severity of prodromal symptoms in the CHR group was assessed using the structured interview for prodromal syndromes (SIPS) and scale of prodromal symptoms (SOPS)40. The SOPS scores consist of four categories: positive, negative, general and disorganised symptoms40. FEP participants met the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder or psychosis, as determined by the SCID-I41 and were within 36 months of their initial diagnosis. In FEP participants, symptom severity was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)42. FEP participants were excluded if their psychotic symptoms were better explained by bipolar disorder or another concurrent DSM-IV Axis I Disorder. HCs were defined as having no history of psychiatric illness or first degree relative with a psychotic disorder, determined by the SCID-I41. Exclusion criteria for all participants included pregnancy or breastfeeding, meeting criteria for alcohol and/or substance abuse disorder, and standard contraindications to MRI. Functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF)43. Neurocognitive performance was assessed using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). All participants underwent urine drug screens for recreational substances at the time of MRI and blood sample collection.

Symptom severity scores

Since the positive items in the SOPS are derived directly from the positive PANSS scale40, we calculated a combined positive score for the CHR and FEP groups, following the approach described previously44.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

As previously described38, 1H-MRS scans were performed at the CAMH Research Imaging Centre in Toronto, Canada with a 3 Tesla General Electric scanner and 8-channel head coil. To minimise head motion, participants were positioned with a soft restraint padding placed around the head and with tape strapped across the forehead. T1-weighted fast spoiled-gradient-echo 3-dimensional sagittal acquisition scans were acquired for each participant (FSPGR sequence, TE = 3.0 ms, TR = 6.7 ms, TI = 650 ms, flip angle = 8°, FOV = 28 cm, acquisition matrix 256 × 256 matrix, slice thickness = 0.9 mm).

The 1H-MRS voxel was positioned in the bilaterial supragenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, 30 × 20 × 15 mm). 1H-MRS spectra were acquired using the standard GE Proton Brain Examination (PROBE) sequence using PRESS (Point Resolved Spectroscopy Sequence), at TE = 35 ms, TR = 2000 ms, number of excitations = 8, bandwidth = 5000 Hz, 4096 data points, 128 water-suppressed, and 16 water-unsuppressed averages. The target water linewidths after shimming were 12 Hz or less. Voxel placement and example spectra are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Spectra were analysed using LCModel Version 6.3–1N45. Pre-processing included eddy-current correction and water-scaling. A standard LCModel basis set for PRESS at 3T (TE = 35 ms), provided by45 was used. This basis set includes simulated spectra for glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), combined glutamate–glutamine (Glx), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), myo-inositol (mI), choline-containing compounds (Cho), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and glutathione (GSH). Gannet 2.0 software (version 2.0, http://gabamrs.com/) co-registered the 1H-MRS voxel onto the corresponding segmented T1-weighted image to extract the grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid in the voxel46. Metabolite values were corrected using the voxel tissue contents using the formula: Mcorr = M * (WM + 1.21 * GM + 1.55 * CSF)/(WM + GM) whereby M = uncorrected metabolite and WM, GM and CSF indicating the white and grey matter and cerebrospinal fluid content. This equation assumes a CSF concentration of 55.556 mol/L47,48.

1H-MRS spectral quality was determined by review of LCModel estimates of spectral full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) and signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio. Predefined criteria for data exclusion were spectra associated with a FWHM or SNR 2 standard deviations respectively above or below the mean values for the dataset, and individual metabolite concentration estimates associated with a Cramer Rao Lower Bounds (CRLB) > 20%. No data were excluded based on these quality criteria.

The primary 1H-MRS outcome variables were glutamate, Glx and NAA. Due to overlapping resonances at 3 Tesla, NAA is reported as the sum of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) and N-acetyl aspartyl glutamate (NAAG).

Peripheral energy measures

Mitochondrial complex I–V protein content in monocyte samples was measured using a multiplex ELISA assay, as previously described19. Protein levels were expressed as a percentage relative to nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (%NNT), to account for potential differences in mitochondrial DNA content between individuals34. Plasma lactate and pyruvate were measured using colorimetric L-Lactate and Pyruvate Assay Kits, also as previously described19, and are reported in nmol/µL.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using RStudio Version 2024.4.2.76449, using the packages tidyverse50, ppcor51, car52, boot53, and Hmisc54. Figures were made using ggplot255.

To address multicollinearity among mitochondrial complexes I–V, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted. Variables were standardised prior to analysis by conversion to Z scores. The number of components retained was determined based on inspection of the scree plot and the eigenvalue > 1 criterion (presented in supplementary materials). Component scores from the retained components were extracted and used in subsequent analyses.

Initial analyses tested for group differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures using T-tests for continuous variables and Chi-Squared Tests for categorical variables, or for non-parametric data Mann–Whitney U Tests and Fisher’s Exact Test respectively. General linear models tested the association between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures across the whole sample, including a group by 1H-MRS metabolite interaction term to test for group differences. Non-parametric data were analysed using Mann-Whitney U tests for group differences and bootstrapped general linear models for associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures, including a group by 1H-MRS metabolite interaction term to test for group differences.

Follow up analyses controlled for group differences in tobacco use with ANCOVAs and additional general linear models, as appropriate. In exploratory analyses, bivariate correlations tested for associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy markers with symptom severity and cognitive performance.

Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures. Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) using a Q threshold of 10% was applied to analyses of associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures with symptom severity and cognitive performance to control for multiple comparisons.

Results

Participant characteristics

Clinical and demographic information is provided in Table 1. The dataset for analysis comprised of 36 CHR + FEP participants and 20 HCs. Peripheral lactate and pyruvate levels were available 29 CHR + FEP participants and 14 HCs. In the CHR + FEP group, three individuals were receiving risperidone, and one was receiving quetiapine. In addition, four participants (two CHR, two FEP) were receiving antidepressants, two participants (one CHR, one FEP) were receiving benzodiazepines, and one CHR participant was receiving lisdexamfetamine. Four participants in the CHR + FEP group and 2 HCs had a positive drug screen for cannabis.

Compared to HCs, the CHR + FEP group had significantly higher tobacco use and lower GAF scores. There were no significant differences between the CHR + FEP group and HCs in the remaining demographic characteristics and cognitive scales (Table 1).

Group differences in 1H-MRS metabolites and energy measures

Of the 56 participants, 55 had complete data across complexes I–V and were included in the PCA; one participant was excluded due to missing data. The PCA for mitochondrial complexes I–V identified two principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1. PC1 explained 48.51% of the variance and showed strong positive loadings from complexes I, II, and IV. PC2 explained 28.50% of the variance, with a strong positive loading from complex V and a strong negative loading from complex III (presented in supplementary materials).

There were no significant group differences in glutamate, Glx, NAA, mitochondrial complex content (PC1 and PC2), lactate, pyruvate or lactate/pyruvate (LP) ratio between the CHR + FEP group and HCs (Table 2), which remained unchanged after covarying for group differences in SNR (presented in supplementary materials). After covarying for group differences in tobacco use, NAA (F (1,53) = 4.254, P = 0.044) and pyruvate (F (1,40) = 4.30, P = 0.045) were higher in the CHR + FEP group compared to HCs.

Relationships between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures

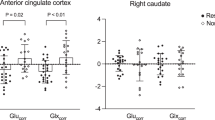

Across the whole sample, ACC Glx was positively associated with both mitochondrial complex content PC1 (Estimate = 0.632, T = 2.16, P = 0.036) and PC2 (Estimate = 0.734, T = 2.22, P = 0.03) (Fig. 1). These associations remained significant after controlling for tobacco use (PC1: Estimate = 0.666, T = 2.24, P = 0.029; PC2: Estimate = 0.753, T = 2.23, P = 0.029). Critically, there were no significant group by PC1 (Estimate = -0.419, T = − 0.920, P = 0.363) or group by PC2 (Estimate = 0.061, T = 0.10, P = 0.923) interaction effects.

Exploratory post hoc analysis indicated that Complex I (rho (56) = 0.329, P = 0.013) and Complex V (rho (56) = 0.346, P = 0.009) content individually correlated with Glx, indicating that these complexes may contribute most strongly to the associations of PC1 and PC2 respectively with Glx.

There were no further significant overall associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures, or group by metabolite interactions, including when covarying for group differences in tobacco use (see supplementary material).

Associations between Glxcorr levels in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and mitochondrial complex content PC1 (Estimate = 0.632, T = 2.155, P = 0.036) and PC2 (Estimate = 0.734, T = 2.22, P = 0.031). The solid black line represents the line of best fit for the total sample. The dashed line represents the fit for the CHR + FEP group and the dotted line represents the fit for the HC group. Data points are plotted by group, with solid circles indicating CHR + FEP participants and unfilled circles indicating HC participants.

Relationships with cognition and symptoms

There were no significant correlations between 1H-MRS metabolites or peripheral energy-related measures and the mean number of categories or perseverative errors on the WCST across the whole sample (presented in supplementary materials). In the CHR + FEP group, there were no significant associations between combined positive symptom severity scores and 1H-MRS metabolites or peripheral energy-related measures (presented in supplementary materials).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) glutamate and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels and peripheral markers of energy-metabolism in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis (CHR) or in the first episode of psychosis (FEP) and healthy controls (HCs). Contrary to our hypotheses, that ACC glutamate metabolites would be negatively associated with peripheral mitochondrial complex content in the CHR + FEP group, we found significant positive associations between Glx (glutamate + glutamine) levels with principal components relating to mitochondrial complex content, which did not differ between groups. NAA, which may provide a marker of metabolic integrity in the ACC, was not significantly associated with peripheral energy measures.

As prior evidence overall indicates a decrease in mitochondrial activity56 and an increase in ACC glutamate metabolites20,23 in the clinical high risk or early stages of psychosis, we hypothesised that these markers would be negatively correlated. However, studies in both CHR and FEP cohorts have revealed mixed findings regarding the direction of change in ACC glutamate metabolites, and it is also possible that glutamate levels differ between these groups. For example, studies of CHR participants have reported both elevated ACC glutamate57 and no differences relative to healthy controls58, and some studies in FEP, particularly those at 7T, have tended to show lower glutamate compared with controls59,60,61,62. The complexity of these findings may reflect clinical and glutamatergic differences between individual participants or cohorts, 1H-MRS methodology including ability to resolve glutamate from glutamine amongst other factors. The limited robustness of a glutamate signal change in CHR or FEP participants may explain the lack of significant difference in glutamate metabolites in the CHR + FEP compared to control group, or a correlation between glutamate and markers of energy metabolism in the CHR + FEP group alone.

Contrary to our hypotheses, we found a significant positive relationship across all participants (CHR, FEP and HCs) between ACC Glx and PC1, reflecting increased content of mitochondrial complexes I, II and IV and Glx and PC2, reflecting the balance between Complex V and III content. Follow-up analysis suggested that positive relationships between content of Complex I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and Complex V (ATP synthase) with ACC Glx may contribute most to these relationships, representing the first and last steps of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. There were no detectable differences in ACC glutamate metabolites or mitochondrial complex content PCs in our CHR + FEP sample compared to HCs, or in the relationship between the mitochondrial PCs and Glx. Our results therefore indicate that peripheral mitochondrial complex content is mainly positively associated with ACC Glx in the absence of marked dysregulation of either marker. This positive relationship is broadly consistent with mechanistic associations between glutamate homeostasis and cellular energy metabolism12,63. It may be that disrupted relationships between peripheral markers of mitochondrial complex content and brain glutamate become more apparent during later stages of psychosis/schizophrenia and may differ in studies examining cohorts with greater average illness burden.

In contrast to the positive associations between ACC Glx and mitochondrial complex PCs, we did not detect associations between ACC glutamatergic metabolites or NAA with peripheral lactate or pyruvate levels. This contrasts with a recent finding of a positive correlation between ACC Glx and NAA and peripheral lactate across patients with schizophrenia and HCs64. It is possible that this may be due to the more limited sample size of our study, in which both lactate and ACC glutamate metabolites were available in a total of 43 participants, compared to 96 participants in64, although our data indicated a non-significant negative relationship. It is also possible that relationships between peripheral lactate and ACC glutamate or NAA only become apparent at later illness stages. According to a recent review5, shifts in metabolic processes may occur in chronic stages of schizophrenia following excessive glutamate signalling and redox dysregulation within early illness stages, which “burn out” in chronic schizophrenia, leading to a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. Shifts in metabolic processes occurring in chronic stages of illness aligns with the evidence showing increases in lactate in chronic schizophrenia65,66 but not in CHR or FEP, compared to HCs19,67 as well as increases in the lactate to pyruvate ratio in post-mortem studies68,69. Future work should examine associations between lactate and glutamate metabolites in psychosis directly within the same brain region, using lactate-optimised 1H-MRS.

In exploratory analysis, we tested whether peripheral energy measures and 1H-MRS metabolites were associated with symptom severity and cognitive function and found no significant associations. In early psychosis, greater mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with higher positive symptom burden and worse cognitive functioning31, however our study mainly included CHR participants and utilised a different set of mitochondrial markers. Some studies have detected relationships between performance on the WCST in established psychosis and glutamate70,71 or NAA72,73. However, due to null or opposite findings and methodological heterogeneity, the overall relationships between 1H-MRS glutamate or NAA and cognition are not well understood74.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the use of ex-vivo measurements of mitochondrial complex content in peripheral blood cells. Most of our sample were unmedicated, which minimised the potential impact of antipsychotic medication on glutamate and NAA75,76,77,78,79 as well as peripheral energy measures80,81.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size, and we may have lacked power to detect further associations or group differences in associations between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral energy measures. A retrospective power analysis based on our dataset indicated that a sample size of 159 participants would be required to detect a small interaction effect (f² = 0.05) between metabolite levels and group, at a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed) with 80% power. To maximise the available data, we combined CHR and FEP participants into one group for analysis, but our 1H-MRS and peripheral measures, or their relationships, may change after the onset of psychosis compared to in the clinical high-risk stage. 1H-MRS is limited in that it measures the total amount of MR-visible glutamate and glutamine in the voxel, whereas neuronal glutamate and glutamine are more tightly and directly coupled to mitochondrial ATP production63. In addition, our assay measured protein content rather than direct enzymatic activity; therefore, results should be interpreted as a proxy for mitochondrial function. Finally, we measured mitochondrial content, pyruvate and lactate in peripheral samples, while glutamate and NAA were assessed in the brain using 1H-MRS. The strength of the association between peripheral measurements of energy metabolism and brain energy metabolism are largely unknown, although previous studies in Parkinson’s disease have shown that alterations in mitochondrial complex I activity are the same in the periphery and in the brain82,83.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found a significant positive relationship between ACC Glx and principal components relating to peripheral mitochondrial complex content, which did not differ between CHR + FEP participants compared to HCs, and was potentially driven by complex I and V. Future studies in larger samples might investigate whether differential relationships between 1H-MRS metabolites and peripheral or central energy measures evolve over the course of psychosis / schizophrenia, potentially in relation to illness burden.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 70, 107–120 (2013).

De Pablo, G. S. et al. Probability of transition to psychosis in individuals at clinical high risk: an updated meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 970–978 (2021).

Cuenod, M. et al. Caught in vicious circles: a perspective on dynamic feed-forward loops driving oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 1886–1897 (2022).

Sarnyai, Z. & Ben-Shachar, D. Schizophrenia a disease of impaired dynamic metabolic flexibility: A new mechanistic framework. Psychiatry Res. 328, 116220 (2024).

Stein, A., Zhu, C., Du, F. & Öngür, D. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of brain energy metabolism in schizophrenia: progression from prodrome to chronic psychosis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 659–669 (2023).

Egerton, A. et al. Glutamate in schizophrenia: neurodevelopmental perspectives and drug development. Schizophr. Res. 223, 59–70 (2020).

McCutcheon, R. A., Krystal, J. H. & Howes, O. D. Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: biology, symptoms and treatment. World Psychiatry. 19, 15–33 (2020).

Hertz, L. & Rothman, D. L. Glucose, lactate, β-hydroxybutyrate, acetate, GABA, and succinate as substrates for synthesis of glutamate and GABA in the glutamine–glutamate/GABA cycle. Adv. Neurobiol. 13, 9–42 (2016).

Sibson, N. R. et al. Stoichiometric coupling of brain glucose metabolism and glutamatergic neuronal activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95, 316–321 (1998).

Yu, Y., Herman, P., Rothman, D. L., Agarwal, D. & Hyder, F. Evaluating the Gray and white matter energy budgets of human brain function. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 38, 1339–1353 (2018).

Attwell, D. & Laughlin, S. B. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 21, 1133–1145 (2001).

Lezmy, J., Harris, J. J. & Attwell, D. Optimising the energetic cost of the glutamatergic synapse. Neuropharmacology 198, 108727 (2021).

Nicholls, D. & Åkerman, K. Mitochondrial calcium transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Bioenerg. 683, 57–88 (1982).

Nicholls, D. G. A role for the mitochondrion in the protection of cells against calcium overload? Prog. Brain Res. 63, 97–106 (1985).

Tiwari, K. D. et al. Effects of high glutamate concentrations on mitochondria of human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 81, 457–465 (2023).

Isaev, N. K., Andreeva, N. A., Stel’mashuk, E. V. & Zorov, D. B. Role of mitochondria in the mechanisms of glutamate toxicity. Biochem. (Moscow). 70, 611–618 (2005).

Ros, J., Pecinska, N., Alessandri, B., Landolt, H. & Fillenz, M. Lactate reduces glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in rat cortex. J. Neurosci. Res. 66, 790–794 (2001).

Izumi, Y. & Zorumski, C. F. Neuroprotective effects of pyruvate following NMDA-mediated excitotoxic insults in hippocampal slices. Neurosci. Lett. 478, 131–135 (2010).

Da Silva, T. et al. Mitochondrial function in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Sci. Rep. 8, 6216 (2018).

Merritt, K. et al. Association of age, antipsychotic medication, and symptom severity in schizophrenia with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy brain glutamate level: a mega-analysis of individual participant-level data. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 667–681 (2021).

Merritt, K. et al. Variability and magnitude of brain glutamate levels in schizophrenia: a meta and mega-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 28, 2039–2048 (2023).

Nakahara, T. et al. Glutamatergic and GABAergic metabolite levels in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 744–757 (2022).

Merritt, K., Egerton, A., Kempton, M. J., Taylor, M. J. & McGuire, P. K. Nature of glutamate alterations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 73, 665–674 (2016).

Rae, C. D. A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem. Res. 39, 1–36 (2014).

Moffett, J. R., Ross, B., Arun, P., Madhavarao, C. N. & Namboodiri, A. M. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: from neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Prog. Neurobiol. 81, 89–131 (2007).

Maddock, R. J. & Buonocore, M. H. MR spectroscopic studies of the brain in psychiatric disorders. In Brain Imaging in Behavioral Neuroscience, 199–251 (2012).

Clark, J. B. N-acetyl aspartate: a marker for neuronal loss or mitochondrial dysfunction. Dev. Neurosci. 20, 271 (1998).

Brugger, S., Davis, J. M., Leucht, S. & Stone, J. M. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and illness stage in schizophrenia—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 69, 495–503 (2011).

Mondino, M., Brunelin, J. & Saoud, M. N-acetyl-aspartate level is decreased in the prefrontal cortex in subjects at-risk for schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry. 4, 99 (2013).

Whitehurst, T. S. et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of N-acetyl aspartate in chronic schizophrenia, first episode of psychosis and high-risk of psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 119, 255–267 (2020).

Khadimallah, I. et al. Mitochondrial, Exosomal miR137-COX6A2 and gamma synchrony as biomarkers of parvalbumin interneurons, psychopathology, and neurocognition in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 27, 1192–1204 (2022).

Ben-Shachar, D. et al. Increased mitochondrial complex I activity in platelets of schizophrenic patients. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2, 245–253 (1999).

Dror, N. et al. State-dependent alterations in mitochondrial complex I activity in platelets: a potential peripheral marker for schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 7, 995–1001 (2002).

Wu, A. et al. Validating mitochondrial electron transport chain content in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Sci. Rep. 9, 12695 (2019).

Huang, J. T. J. et al. CSF metabolic and proteomic profiles in patients prodromal for psychosis. PLoS One. 2, e756 (2007).

Onozato, M. et al. Serum D- and L‐lactate, pyruvate and glucose levels in individuals with at‐risk mental state and correlations with clinical symptoms. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 14, 410–417 (2020).

Jiang, J. et al. Leukocyte proteomic profiling in first-episode schizophrenia patients: does oxidative stress play central roles in the pathophysiology network of schizophrenia? (2019).

Watts, J. J. et al. Evidence that cannabis exposure, abuse, and dependence are related to glutamate metabolism and glial function in the anterior cingulate cortex: a 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 764 (2020).

Da Silva, T. et al. Genetically predicted brain C4A expression is associated with TSPO and hippocampal morphology. Biol. Psychiatry. 90, 652–660 (2021).

Miller, T. J. et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull. 29, 703–715 (2003).

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) (Biometric Research Department, 1995).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Hall, R. C. Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics 36, 267–275 (1995).

Schobel, S. A. et al. Differential targeting of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampal formation by schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 66, 938–946 (2009).

Provencher, S. W. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Med. 30, 672–679 (1993).

Egerton, A. et al. Dopamine and glutamate in antipsychotic-responsive compared with antipsychotic-nonresponsive psychosis: a multicenter positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study (STRATA). Schizophr. Bull. 47, 505–516 (2021).

Kreis, R., Ernst, T. & Ross, B. D. Development of the human brain: in vivo quantification of metabolite and water content with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 30, 424–437 (1993).

Gasparovic, C. et al. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 55, 1219–1226 (2006).

Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 2024.4.2.764). Posit Software, PBC (2024). https://posit.co/

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open. Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Gordon, M. ppcor: an R package for a fast calculation to semipartial and partial correlations. R package version 1.1 (2019).

Fox, J., Weisberg, S. & An, R. Companion To Applied Regression, 3rd edn (Sage, 2019).

Canty, A. & Ripley, B. D. boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) functions. R package version 1.3–28 (2022).

Harrell, F. E. Jr. Hmisc: Harrell miscellaneous. R package version 5.1-3 (2024).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

Rajasekaran, A., Venkatasubramanian, G., Berk, M. & Debnath, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: pathways, mechanisms and implications. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 48, 10–21 (2015).

Fan, L. et al. Glutamate levels and symptom burden in high-risk and first-episode schizophrenia: a dual-voxel study of the anterior cingulate cortex. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 49, E367–E376 (2024).

McCutcheon, R. A., Merritt, K. & Howes, O. D. Dopamine and glutamate in individuals at high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis of in vivo imaging findings and their variability compared to controls. World Psychiatry. 20, 405–416 (2021).

Wang, A. M. et al. Assessing brain metabolism with 7-T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with first-episode psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 76, 314–323 (2019).

Reid, M. A. et al. 7T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the anterior cingulate cortex in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 180–189 (2019).

Godlewska, B. R. et al. Brain glutamate concentration in men with early psychosis: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy case–control study at 7 T. Transl. Psychiatry. 11, 367 (2021).

Jeon, P. et al. Progressive changes in glutamate concentration in early stages of schizophrenia: a longitudinal 7-Tesla MRS study. Schizophr. Bull. Open. 2, sgaa072 (2021).

Andersen, J. V. et al. Glutamate metabolism and recycling at the excitatory synapse in health and neurodegeneration. Neuropharmacology 196, 108719 (2021).

Krzyściak, W. et al. Association of blood metabolomics biomarkers with brain metabolites and patient-reported outcomes as a new approach in individualized diagnosis of schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2294 (2024).

Rowland, L. M. et al. Elevated brain lactate in schizophrenia: a 7 T magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Transl. Psychiatry. 6, e967 (2016).

Wijtenburg, S. A. et al. Metabolite alterations in adults with schizophrenia, first degree relatives, and healthy controls: a multi-region 7T MRS study. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 656459 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Longitudinal changes in brain metabolites in healthy controls and patients with first episode psychosis: a 7-Tesla MRS study. Mol. Psychiatry. 28, 2018–2029 (2023).

Dean, B., Thomas, N., Scarr, E. & Udawela, M. Evidence for impaired glucose metabolism in the striatum, obtained postmortem, from some subjects with schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e949 (2016).

Park, H. J., Choi, I. & Leem, K. H. Decreased brain pH and pathophysiology in schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8358 (2021).

Dempster, K. et al. Glutamatergic metabolite correlations with neuropsychological tests in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 233, 180–185 (2015).

Shirayama, Y. et al. Specific metabolites in the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Neuroimage 49, 2783–2790 (2010).

Braus, D. F. et al. Functioning and neuronal viability of the anterior cingulate neurons following antipsychotic treatment: MR-spectroscopic imaging in chronic schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 12, 145–152 (2002).

Galińska, B. et al. Relationship between frontal N-acetylaspartate and cognitive deficits in first-episode schizophrenia. Med. Sci. Monit. 13 (Suppl 1), 11–16 (2007).

Reddy-Thootkur, M., Kraguljac, N. V. & Lahti, A. C. The role of glutamate and GABA in cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders – a systematic review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Schizophr. Res. 249, 74–84 (2022).

Arun, P., Madhavarao, C. N., Moffett, J. R. & Namboodiri, A. M. Antipsychotic drugs increase N-acetylaspartate and N‐acetylaspartylglutamate in SH‐SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 106, 1669–1680 (2008).

Bustillo, J. R. et al. Longitudinal follow-up of neurochemical changes during the first year of antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia patients with minimal previous medication exposure. Schizophr. Res. 58, 313–321 (2002).

Egerton, A., Modinos, G., Ferrera, D. & McGuire, P. Neuroimaging studies of GABA in schizophrenia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry. 7, e1147 (2017).

Goto, N. et al. Six-month treatment with atypical antipsychotic drugs decreased frontal-lobe levels of glutamate plus glutamine in early-stage first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 8, 119 (2012).

Kubota, M., Moriguchi, S., Takahata, K., Nakajima, S. & Horita, N. Treatment effects on neurometabolite levels in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis dataset of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Data Brief. 31, 105862 (2020).

Casademont, J. et al. Neuroleptic treatment effect on mitochondrial electron transport chain: peripheral blood mononuclear cells analysis in psychotic patients. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27, 284–288 (2007).

Halim, N. D. et al. Increased lactate levels and reduced pH in postmortem brains of schizophrenics: medication confounds. J. Neurosci. Methods. 169, 208–213 (2008).

Parker, W. D., Boyson, S. J. & Parks, J. K. Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 26, 719–723 (1989).

Schapira, A. et al. Anatomic and disease specificity of NADH CoQ1 reductase (complex I) deficiency in parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 55, 2142–2145 (1990).

Funding

This work was partially funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant (APP400704), and also represents independent research partly supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. B.K. is supported by a UK Medical Research Council PhD studentship (MR/N013700/1). For the purposes of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. B.K. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, and writing-original draft. M.J.K. contributed to supervision and writing-review and editing. S.K.M. contributed to project administration and writing-review and editing. A.E. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, and writing-review and editing. R.M. contributed to funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, and writing-review and editing. A.E. and R.M. jointly supervised the project and share senior authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.E. has received consultancy fees from Leal Therapeutics. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

King, B., Kempton, M.J., Man, S.K. et al. Glutamate, NAA, and energy metabolism in clinical high risk and first episode psychosis. Sci Rep 15, 42031 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22845-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22845-y