Abstract

The increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome among office workers in Ethiopia underscores the urgent need for tailored health interventions. This study aimed to implement a healthy lifestyle education intervention designed to reduce the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and evaluate changes in participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and risk factors, as well as improvements in healthy lifestyle practices. This 9-month institution-based, single-masked, cluster-randomised controlled trial was conducted among bank employees in Bahir Dar. A total of 226 participants were screened based on waist circumference and blood pressure. The intervention was a personalised educational program focused on lifestyle modifications, delivered by health promotion experts, while the control group received general health advice based on the guidelines on clinical and programmatic management of major NCDs. Outcomes were assessed at baseline and after 9 months, with 207 participants included in the final analysis using an intention-to-treat approach, and generalised estimating equations to assess the intervention’s effect between groups. The intervention group exhibited significant improvements, with decreases in waist circumference (5.33 cm), systolic blood pressure (6.96 mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (4·21 mmHg), total cholesterol (34.12 mg/dL), and low- density lipoprotein cholesterol (20·68 mg/dl) (all p < 0.0001). Knowledge scores increased by 7.29 points, fruit intake rose from 0.74 to 1.21 portions, and vegetable intake grew from 1.10 to 1.77 portions. Participation in moderate exercise rose from 29.52% to 53.33%. In contrast, the control group showed modest improvements in some components of metabolic syndrome risk factors. However, there were no significant changes in triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, and stress management, while high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels unfavorably declined in both groups. This study highlighted the impact of a tailored workplace-based healthy lifestyle education intervention on lifestyle behaviors and metabolic syndrome risk factors. The intervention led to positive changes in several behaviors and reduced some risk factors. However, it did not significantly improve triglyceride and fasting blood glucose levels, and there was an unexpected decrease in high density lipoprotein cholesterol. This unexpected decrease of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol may result from lifestyle shifts, including reduced fatty diet intake and rapid weight loss, and other metabolic adaptation process. Future research should focus on targeted strategies and long-term interventions to address these unexpected outcomes.

Trial registration: ACTRN12623000409673p, registered April 24, 2023 and is completed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has been swift, with 43 million deaths in 2021, accounting for 75% of all non-pandemic fatalities. Among these, 18 million deaths were in individuals under 70, with 82% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which represent 73% of all NCD-related deaths1.

A major driver of this trend is metabolic syndrome, characterised by obesity, high blood glucose, dyslipidemia, and hypertension2. It increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases by 2·5 times and the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes by fivefold3. The syndrome is a significant health threat, affecting over one billion people globally4, primarily due to poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol consumption5. Transitions from traditional to Western lifestyles in LMICs are increasing risk factors and escalating metabolic syndrome6. This trend places a double burden on LMICs, as these countries are concurrently addressing the challenges associated with infectious diseases7.

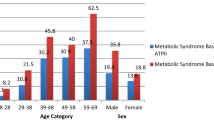

Furthermore, rapid urbanisation exacerbates the issue by encouraging a shift from physically demanding agricultural jobs to sedentary, high-stress office work4,8. The shift from physically demanding jobs to sedentary office work has significantly raised the risk of metabolic syndrome9. Among office workers, prevalence rates are troubling, ranging from 20% to over 30%10,11,12. In Ethiopia, the prevalence rates among office workers are 27·6% and 16·7%, using the International Diabetic Federation (IDF) and National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) criteria, respectively13.

Individuals’ knowledge, attitudes about metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and risk factors, as well as their practices related to healthy lifestyles, are also influential factors in developing metabolic syndrome14.

A workplace health intervention among office workers presents a promising approach to fostering healthier behaviours and improving overall well-being15.

Most workplace-based health interventions have been conducted in middle- and high-income countries, with limited assessment of their effects on knowledge, attitudes toward metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and risk factors, as well as practices related to healthy lifestyles. Although the government of Ethiopia has endorsed policies, strategies, and guidelines to prevent and control NCDs16, evidence on the effectiveness workplace lifestyle education intervention in Ethiopia is scarce, highlighting the need for context-specific research on reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors and improving knowledge and attitudes about metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and risk factors, as well as practices related to healthy lifestyles.

The objectives of this study are: (1) to develop and test the effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle intervention in reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors among office workers in Ethiopia. (2) to evaluate and compare knowledge and attitudes regarding metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and risk factors, as well as practices related to healthy lifestyles before and after the intervention and between the control and intervention groups among office workers in Ethiopia.

The findings will aid policymakers in enhancing management strategies and serve as a resource for stakeholders addressing metabolic syndrome while also providing a reference for future studies and effective interventions for at-risk populations.

Method

Study design

This institution-based cluster randomised controlled trial aimed to develop and test the effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, enhance knowledge and positive attitudes regarding metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and risk factors, as well as promote the practice of healthy lifestyles. The study took place in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, located 565 km northwest of Addis Ababa. Bahir Dar serves as the capital of the Amhara region, housing 210 bank branches that employ 2,310 workers. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12623000409673p). This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Australian National University Human Ethics Committee (2022/845) and Bahir Dar University Institutional Review Board (792/2023). Detailed trial protocol is published elsewhere17, and findings are presented following CONSORT 2025 Statement: guideline for reporting randomised trials18. We selected this checklist because it is specifically designed for randomised controlled trials, promoting clear and transparent reporting of methods and findings. By ensuring comprehensive coverage of essential trial aspects, it reduces the risk of incomplete or biased information, ultimately enhancing research quality (Supplementary file 1).

Changes to the protocol

The study design shifted from a parallel randomised controlled trial to a cluster randomised format due to a typographical error in the protocol. Knowledge, attitudes, stress levels, and fruit and vegetable portion consumption were reclassified as primary continuous outcomes to better capture mean changes attributable to the intervention. This adjustment emphasises the importance of these factors in influencing metabolic disease risk and driving meaningful behavioural change.

Participants

The participants were both private and government banks in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. Previous research indicates that this group is at high risk for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease19,20,21. Between September 29, 2023, and January 1, 2024, 226 participants were screened, enrolled, and assigned to groups based on their workplace through a systematic recruitment process. Recruitment involved sending official letters from the local health department office of the Ministry of Health within the city administration to district bank headquarters and communicating with branch managers. Potential participants were approached in person and informed about the study’s objectives, criteria, benefits, risks, and ethical considerations to ensure that they made informed decisions. Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from each participant, confirming their voluntary participation and understanding of the study. Participants were screened for obesity and high blood pressure by measuring waist circumference and blood pressure at their workplace by a trained BSc nurse under the supervision of the principal investigator. Those with a waist circumference over 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women and/or blood pressure readings of 130/85 mmHg or higher were eligible. However, potential participants were excluded if they had dietary restrictions, contraindications to physical activity due to musculoskeletal, neurological, vascular, pulmonary, or cardiac conditions, were pregnant or planning to become pregnant, had severe psychiatric disorders, significant cognitive impairments, or were unable to commit to the entire program. Gender data were collected through a self-report questionnaire.

Patient and public involvement

There was no involvement of patients or the public in the planning, development, or implementation of this intervention.

Randomisation and masking

Bahir Dar city is divided into two distinct geographical clusters by the Abay River. All banks in one area were assigned as control settings through a random selection process using a coin-tossing method conducted by the principal investigator, while banks in the other area were assigned as intervention sites. Each participant was subsequently screened according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria until the target sample size was reached. Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not feasible to blind participants to the intervention itself; however, they remained unaware of their group assignment. The nurses responsible for data collection and the laboratory personnel, and intervention provider were blinded to the group allocation.

Procedures

Development of the intervention

This intervention was developed with the collaboration of expertise in nutrition, social psychology and sport sciences, and grounded in the theoretical frameworks of the Health Belief Model (HBM) which encompasses essential components such as perceived susceptibility (the belief regarding the likelihood of experiencing a risk or developing a condition), perceived severity (the belief about the seriousness of a condition and its potential consequences), perceived benefits (the belief in the effectiveness of recommended actions to reduce risk or severity), perceived barriers (the tangible and psychological costs associated with these actions), cues to action (strategies designed to activate readiness for change), and self-efficacy (the confidence in one’s ability to take action)22, and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) which encompasses key constructs, including reciprocal determinism (the dynamic interaction among an individual’s behaviour, their environment, and personal factors), behavioural capability (the knowledge and skills necessary to perform specific behaviours), expectations (beliefs about the outcomes of behaviour change), reinforcements (the consequences that affect the likelihood of behaviour repetition), and self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to successfully perform a specific behaviour)23 (Fig. 1).

Intervention.

For intervention group

The intervention was a one-on-one education program addressing metabolic syndrome, its risk factors, and prevention strategies, focusing on lifestyle changes such as healthy eating, exercise, alcohol consumption, quitting smoking, and stress management. Delivered by three health promotion experts, the sessions lasted 1:45 to 2 h, one -to-one intervention was ran from September 29, 2023, to January 1, 2024. A printed PowerPoint developed with input from the experts were also given. Text messages were sent biweekly to reinforce key concepts and encouraged to record their activities using a provided template and invited to ask questions and seek advice for 9 months. The principal investigator held review meetings at the 3rd and 6th months to revisit key points and address any concerns. Feasibility and acceptability data for the intervention were assessed at the 6-month mark. Additionally, data about fidelity and contextual factors influencing the intervention’s implementation were assessed during each review meeting and at the conclusion of the intervention.

For the control group

A BSc nurse provided individual general health advice following national guidelines for non-pharmacological management of each component of metabolic syndrome24. At the end of the study, control group participants were also given the full educational package.

Outcomes

Central obesity: defined as a waist circumference (WC) > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women25. Blood pressure (BP): defined as BP ≥ 130/85 mmHg25,26. Biochemical markers: Fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 110 mg/dl, total cholesterol (T. Chol) > 200 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) < 40 mg/dl in men and < 50 mg/dl in women, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-c) > 100 mg/dl, and triglycerides (TGL) ≥ 150 mg/dl25, as well as knowledge, and attitudes towards metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and risk factors and practice of healthy lifestyles. The outcomes were measured at three time points: at baseline, the 6th month, and 9th months after the intervention. However, this discussion will focus only on the data collected at baseline and 9th months after the intervention. The data gathered during the 6th month, which pertained to the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, are under review elsewhere.

At baseline, socio-demographic data (Age, sex, marital status, educational status, work experience, working hours per day, monthly income, religion, and background health conditions) were measured using questionnaires.

At baseline and the 9th month, WC: was measured using a tape measure at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest, or the maximum abdominal extension.

BP: was assessed by taking three measurements with an appropriately sized sphygmomanometer. The first measurement was conducted after a 5-min rest, with subsequent measurements spaced 5 min apart. The mean systolic and diastolic BP values were used for interpretation.

Biochemical markers: In the early morning after a night of fasting, 5 mL venous blood samples were collected from each participant following strict sanitation protocols. A laboratory technologist transported the samples to the hospital, where serum was separated to assess key metabolic parameters, including FBG, T. Chol, HDL-c, and TGL. LDL-c levels were calculated indirectly. Baseline analysis was conducted at Bahir Dar University Teaching Hospital, and the end-line data analysis occurred at Gamby Teaching Hospital due to a lack of reagents at Bahir Dar University Teaching Hospital during that period.

Knowledge and attitude: Knowledge and attitudes regarding metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and risk factors were assessed using a validated 43-item questionnaire, originally developed and tested in India27, with minor modifications to include specific questions about metabolic syndrome and its risk factors. Knowledge was assessed using 36 questions, with a maximum score of 36 points. Responses were scored as 1 for correct answers and 0 for incorrect answers. Attitude was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale across 13 questions, yielding a maximum score of 65. Practice: Dietary habits, alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical activity were assessed with a short-form food frequency questionnaire28. For the analysis, dietary and alcohol consumption patterns were categorised into distinct classifications. Dietary patterns were deemed “regular” if participants reported consumption of specific items 4–6 times per week or more, while those reporting consumption less 4–6 times per week were classified as “irregular”. Alcohol consumption was divided into two categories: “less than 14 units per week” and “more than 14 units per week”. Stress were measured using the Perceived Stress Scale29. The data were collected by a trained BSc nurse and laboratory technologists.

Statistical analyses

The total sample size was 226 participants, divided equally into two groups of 113. This was determined using a sample size calculation for trials with continuous outcomes30. Data were entered twice into Epidata 3.1 and exported to STATA 17 for cleaning and analysis. After excluding nineteen participants (8 from the intervention group and 11 from the control group) due to loss to follow-up, a final sample of 207 participants was retained (105 in the intervention group and 102 in the control group). Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the baseline characteristics of both groups. To assess baseline differences, we employed the T-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables.

To determine differences in continuous variables, paired t-tests were employed for before-and-after comparisons. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare differences between the intervention and control groups, assuming equal variances. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank and Rank-Sum tests were used as alternatives. Normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed with Q-Q plots and Levene’s Test. Proportion tests were used to compare differences between the baseline and end-line, as well as between the intervention and control groups at the end-line, for categorical outcomes.

The change in the difference in continuous outcomes between the intervention and control groups was also assessed using Generalised Estimating Equations (GEEs), employing a Gaussian identity link function, an unstructured correlation structure, and robust standard errors. The intervention and control groups were coded as (1/0), and an interaction term between the intervention and time was created to evaluate the impact of the intervention. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed.

Role of the funding source

This study was supported by the Australian National University Scholarship. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Between September 29, 2023, and January 1, 2024, 112 bank branches and 1,574 employees were approached. Out of these, 864 employees underwent measurements for blood pressure and obesity, but 607 were excluded due to normal readings. Additionally, 31 participants (27 male and 4 female) were excluded for various reasons: 18 did not consent to provide a blood sample, 3 had neurological issues, 2 experienced musculoskeletal problems, 2 had cardiac conditions, 3 had respiratory issues, 2 were pregnant, and 1 was planning to become pregnant. Finally, 226 participants were included in the trial, with 113 assigned to each group. The intervention ran from November 29, 2023, to January 1, 2024, with follow-up continuing until October 15, 2024. The trial is completed and data analysis was performed on 207 participants (Fig. 2).

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The intervention group had a mean age of 39·71 years (± 7·57), while the control group had an average age of 39·18 years (± 7·99). The intervention group consisted of 92 males (87·62%) and 13 females (12·38%), while the control group comprised 85 males (83·33%) and 17 females (16·67%). All participants were non-smokers (Table 1).

Table 2 summarises the continuous outcomes results. The levels of risk factors for metabolic syndrome, lipid profiles, and KAP at baseline and end-line were compared, and the differences between groups were compared by the intervention status.

For the intervention group, we observed significant improvements in several health metrics. The WC significantly decreased from a baseline mean of 101·57 cm to 96·24 cm, resulting in a difference of 5·33 cm (p < 0·0001). SBP also exhibited a substantial reduction from 135·56 mmHg to 128·59 mmHg, with a difference of 6·96 mmHg (p < 0·0001). Similarly, DBP declined from 89·87 mmHg to 85·66 mmHg, indicating a reduction of 4·21 mmHg (p < 0·0001). T. Chol levels decreased substantially by 34·12 mg/dl, falling from 212·33 mg/dl to 178·21 mg/dl (p < 0·0001). LDL-c experienced a significant decline of 20·68 mg/dl, dropping from 132·59 mg/dl to 111·91 mg/dl (p < 0·0001). Furthermore, knowledge improved significantly in the intervention group, with a change of 7·29 points (p < 0·0001). Regarding dietary habits, the intervention group showed notable improvements in the consumption of fruit and vegetable portion. Fruit consumption increased significantly from 0·74 to 1·21 portions (p = 0·0072), while vegetable portions rose from 1·10 to 1·77 portions (p < 0·0001). No significant changes were observed in TGL, FBG levels, attitude, stress management, and sitting time.

The control group also showed modest changes in several metabolic syndrome risk factors. WC decreased by 4·24 cm (p = 0·0005), SBP was reduced by 4·34 mmHg (p = 0·0067), and DBP decreased by 3·60 mmHg (p = 0·0012). Additionally, T. Chol dropped by 19·61 mg/dl (p < 0·0001), and low-LDL levels decreased by 16·35 mg/dl (p < 0·0001). However, TGL rose by 11·01 mg/dl (p = 0·2549), and there was a significant decline in fruit and vegetable consumption, with portions decreasing by 0·53 (p = 0·0217) and 0·90 (p < 0·0001), respectively. HDL decreased unfavourably in both groups, primarily showing a significant decline of 10·91 mg/dl (p < 0·0001) in the intervention group. The difference-in-differences analysis highlights the effectiveness of the intervention in improving T. Chol level, knowledge, and behavioural outcomes. The intervention group demonstrated a significant reduction in total cholesterol level (14·52 mg/dl; p = 0·0054) as well as noteworthy increases in knowledge (6·96; p < 0·0001), fruit consumption (1·00 portion; p = 0·0005), and vegetable consumption (1·34 portions; p < 0·0001) compared to the control group (Table 2).

Table 3 presents a summary of the proportions and mean differences of the categorical outcomes, comparing pre and post intervention results, as well as differences between the control and intervention groups at the endline.

The intervention group experienced significant improvements in dietary habits and physical activity compared to the baseline. Regular fruit consumption rose from 4·76% to 20·00% (mean difference 0·152, p = 0·0008), fruit juice intake increased from 3·81% to 16·19% (mean difference 0·124, p = 0·0028), and vegetable consumption improved from 8·57% to 28·57% (mean difference 0·20, p = 0·0002). Additionally, there was a borderline significant reduction in oil and fat intake, decreasing from 59·05% to 45·71% (mean difference 0·133, p = 0·0531).

Improvements were also noted in physical activity, with moderate exercise participation increasing from 29·52% to 53·33% (mean difference, 0·215; p = 0·0019) and vigorous exercise increasing from 11·43% to 26·67% (mean difference, 0·152; p = 0·0049).

The control group showed no significant changes in healthy dietary or exercise patterns. In contrast, fast food and pastry consumption increased from 2·94% to 13·73% (mean difference, 10·79%; p = 0·0053), while egg consumption also showed a borderline increase from 1·96% to 7·84% (mean difference, 0·068; p = 0·0517) compared to the baseline.

By the end of the intervention, significant improvements were observed in the intervention group compared to the control group. Regular fruit consumption increased to 20·00% in the intervention group compared to 7·84% in the control group (mean difference, 0·122; p = 0·0118). Vegetable consumption increased to 28·57% in the intervention group, compared to 13·73% in the control group (mean difference, 0·148; p = 0·0090). Conversely, 13·73% of the control group reported regular consumption of fast food and pastries, compared to 1·90% in the intervention group (mean difference, 0·118; p = 0·0015).

The intervention group also showed notable improvements in levels of physical exercise, with p-values of 0·0216 for light exercise, 0·0202 for moderate exercise, and 0·0035 for vigorous exercise. No significant differences were found in alcohol consumption patterns, with approximately 93% of participants in both groups reporting less than 14 units of alcohol per week (p = 0·9552) (Table 3).

Table 4 presents the results of the impact evaluation for continuous outcomes, comparing the intervention and control groups. The analysis utilised the Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) model, adjusting for age, sex, marital status, work experience, income, educational status, and background health conditions (diabetes, hypertension, and cholesterol).

The results indicate significant effects of the intervention over time on total cholesterol, knowledge, fruit and vegetable portion consumption. The intervention resulted in a notable decrease in t.chol (β = − 14·249, p = 0·006, 95% CI − 24·458 to − 4·039), an increase in knowledge (β = 7·194, p < 0·001, 95% CI 5·351–9·037), and improvements in fruit portion consumption (β = 1·043, p < 0·001, 95% CI 0·482–1·603) and vegetable portion consumption (β = 1·360, p < 0·001, 95% CI 0·734–1·987). Conversely, there was also a significant reduction in HDL cholesterol (β = − 5·055, p < 0·001, 95% CI − 7·805 to − 2·306). No significant changes were observed in WC, BP, LDL-c, TGL, FBG, attitude, stress management, and sitting time per day (Table 4).

Discussion

This trial offers strong evidence regarding the effectiveness of a workplace-based healthy lifestyle intervention in reducing the metabolic risk factors and promoting healthy behaviours in low-income country contexts. The findings will serve as valuable input for the design and implementation of future workplace health intervention programs, both in similar contexts and beyond.

The study found significant reductions in key metabolic syndrome risk factors in the intervention group, including WC, SBP, DBP, T. Chol, and LDL-c, compared to baseline measurements.

These findings align with previous workplace based interventions, including a study among university staff in Jimma, Ethiopia31, studies in Taiwan32 and from Iran, which reported reductions in WC and T.CHOL levels33.

The findings of our study demonstrate that workplace health education intervention effectively reduces metabolic syndrome risk factors and improves lipid profiles. The significant decreases in these biomarkers underscore the critical role of structured health education programs in reducing the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Thus, this study supports workplace health initiatives as a valuable strategy for preventing chronic diseases. The control group also showed modest changes in metabolic risk factors from baseline measurements. However, these improvements were less pronounced than those observed in the intervention group, even with some increments in TGL levels. This outcome suggests that essential health interventions such as providing general health advice, conducting screening activities, and informing participants about their health status effectively reduce metabolic syndrome risk factors. Thus, continuous workplace health screening and education that motivate individuals to adopt healthier lifestyle practices are important in preventing the development of metabolic syndrome, even in the absence of structured, in-depth programs, as trialled in this study.

Despite the significant changes in the above risk factors, the intervention did not yield significant improvements in TGL and FBG levels, and an unexpected reduction in HDL levels was observed. These observations align with findings from other studies. One study34 noted that TGL levels remained unchanged post-intervention among participants receiving the similar intervention. Another study conducted in Iran noted a decrease in mean HDL-C levels along with a rise in FBG levels among the intervention group33.

Understanding the mechanisms behind the insignificant changes in TGL, FBG, and the unexpected decrease in HDL-c is crucial for guiding future interventions. The decrease in HDL-c is particularly noteworthy, as it is generally regarded as a protective factor for cardiovascular disease. Several factors likely contributed to these outcomes, including dietary focus, carbohydrate consumption, metabolic adaptations, impact of rapid weight loss, exercise variability, and the duration of the intervention. The intervention aimed to reduce overall fat intake but did not sufficiently prioritise the replacement of unhealthy fats with healthier options, which may have limited potential benefits on HDL-c levels. Participants also failed to significantly reduce their consumption of sweets and high-carbohydrate foods (injera, bread, rice, and noodles), which can lead to increased TGL and FBG levels while lowering HDL-c35. Metabolic adaptations in response to variations in energy intake or expenditure may have impeded improvements in HDL-c36, as individuals lose weight or modify their dietary patterns, the body can undergo metabolic changes that initially disrupt lipid profiles. These adaptations may encompass alterations in liver function as well as modifications in the synthesis and clearance of lipoproteins37,38. Insufficient improvements in insulin sensitivity may result in minimal changes in FBG and TGL due to increased triglyceride production37,39. Rapid weight loss can also raise TGL by mobilising fatty acids from adipose tissue, negatively impacting HDL levels39,40. Furthermore, variations in exercise intensity and type may yield different effects on HDL-c levels, particularly if participants engaged in high-intensity workouts without adequate recovery or nutrition41.

Lastly, the duration of the intervention may not have been long enough to achieve significant improvements in lipid profiles and blood glucose levels, underscoring the need for longer interventions to foster meaningful lifestyle changes and metabolic adaptations. To address these challenges, future interventions should emphasise balanced dietary guidance that includes healthy fats and educating participants about the sources of these foods. Implementing gradual weight loss strategies is important to minimise rapid metabolic changes, allowing for more stable adaptations and the maintenance of HDL-c levels. Tailored exercise programs should be designed based on individual fitness levels, incorporating a mix of aerobic and resistance training to optimise improvements in lipid profiles. Additionally, regular monitoring of lipid levels throughout the intervention provides valuable feedback; if HDL-c levels decrease, adjustments can be made in real-time to dietary and activity recommendations.

Moreover, extending the duration of interventions is crucial for facilitating transformative lifestyle changes that reshape dietary choices, ultimately leading to lower TGL levels and improved insulin sensitivity.

The difference-in-difference analysis indicates that the mean levels of T. Chol, knowledge acquisition, and consumption of fruit and vegetable portions exhibited statistically significant differences in the intervention group compared to the control group. Furthermore, at the end of the intervention, significant enhancements in fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity engagement were observed relative to the control group.

These findings suggest an optimistic path: extending the duration of the intervention could yield even more significant improvements in risk factors linked to metabolic syndrome. The increase in knowledge, coupled with substantial behavioural changes in dietary practices and physical activity, serves as a foundation in the transformation of metabolic health.

On the other hand, no significant changes were detected in participants’ attitudes, stress management, or the reduction of alcohol consumption. Several factors may account for these non-significant changes.

Modifying one’s attitude is an inherently gradual process that typically requires sustained effort over time to establish42. The ongoing political conflict between the federal government and the Amhara Fano (the armed force struggling for freedom) exacerbates stress levels by disrupting financial systems and fostering insecurity. At the same time, regular physical activity remains unfeasible without a contextually aware approach for home and workplace exercises. Our previous qualitative study (under review) highlighted that security concerns significantly hinder outdoor physical exercise.

This situation highlights the negative impact of political instability on public health, as it increases the risk of chronic conditions by hindering the adoption of healthy lifestyles. Context-specific interventions, such as home-based exercise programs, may effectively address these challenges and help prevent chronic diseases in these circumstances.

The assessment of alcohol consumption focused on participants’ experiences over the past seven days, coinciding with the Ethiopian New Year and a True Cross holiday, when social gatherings typically increase alcohol intake43. This cultural context likely contributed to the non-significant reduction observed. Additionally, unmanaged stress may lead individuals to consume more alcohol as a coping mechanism44.

This randomised controlled trial provides crucial evidence on the effectiveness of a contextually tailored workplace health education intervention in reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors and fostering healthier lifestyles in low-income settings. Although the effectiveness was tested in Ethiopia, it is applicable to other nations going through health transitions brought on by fast urbanisation and the switch from physically demanding agricultural work to sedentary, high-stress office work. These revelations support the global efforts that try to prevent NCDs. Policymakers should prioritise the creation of health-promoting workplace environments by developing and implementing structured workplace health intervention programs. Additionally, implementing general health advice, including regular health screenings, is essential to address the increasing burden of metabolic syndrome and related NCDs. Future studies should look at these interventions’ long-term effects on health outcomes, as well as their scalability and sustainability in a variety of working contexts. This will guarantee that successful strategies may be modified and used in diverse settings to improve public health worldwide.

A key strength of this study is its focus on low- and middle-income countries, assessing knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported behaviors related to diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and stress management, rather than solely measuring the effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle education intervention for metabolic syndrome risk reduction among office workers. The study is not without limitations and it is important to acknowledge those limitations. First, we employed a cluster randomised controlled trial design, which has inherent limitations due to intra-cluster correlation. Individuals within the same cluster may share similarities that can lead to correlated outcomes, causing standard errors to be underestimated and inflating the risk of type I errors. This correlation can diminish the apparent effectiveness of the intervention, as the outcomes may not reflect true differences between groups. To mitigate these effects, we utilised statistical methods such as generalized estimating equations, which account for the clustering. However, it is important to note that more participants may be required to achieve the same statistical power as individual randomisation due to the reduced effective sample size associated with clustering. Therefore, careful planning for a larger sample size during the study design phase is crucial to ensure adequate power and robustness of the results.

Second, the data on healthy lifestyle behaviors were collected through self-report methods, which are susceptible to various biases. These include social desirability bias, where participants may overreport positive behaviors, and recall bias, where they may struggle to accurately remember past behaviors. Additionally, response bias can occur if participants provide answers they believe are expected rather than their true behaviors. To enhance the reliability of future study findings, we recommend using objective measures, such as pedometers and food diaries with cross-checking, alongside self-reported data. Providing training for participants can also help improve the accuracy of their self-reports and reduce biases. Third, there is a potential for information contamination between groups, as complete control over this factor is challenging due to the intervention’s nature.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the impact of a tailored workplace-based healthy lifestyle education intervention on lifestyle behaviors and risk factors for metabolic syndrome. The intervention successfully achieved positive changes in several lifestyle behaviors and reduced certain metabolic syndrome risk factors. However, it did not lead to significant improvements in others, such as TGL and FBG levels, and there was an unexpected decrease in HDL-c. This HDL-c decrease may be linked to shifts in lifestyle, including reduced intake of fatty diets and rapid weight loss, as well as other metabolic adaptation processes. This outcome underscores the need for careful substitution of unhealthy fats with healthier options. Future studies should focus on targeted strategies and long-term interventions to address the unexpected findings and enhance improvements in TGL and FBG levels. Additionally, the absence of a supportive work environment for adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviours emerged as a significant barrier. It is crucial to develop integrated policies and programs that foster health-promoting workplace environments to overcome this problem.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Australian National University Scholarship.

Ethical considerations and consent to participate

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical approvals obtained from the Human Ethics Committee at the Australian National University and the Institutional Review Board at Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Sciences (with unique protocol IDs 2022/845 and 792/2023, respectively). A cooperative letter was secured from the Zonal Health Bureau of the Bahir Dar City administration. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12623000409673p), and the established protocol for this trial has been published separately. All participants provided written informed consent before participating.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyses during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.The study protocol is available for download at (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0307659).

References

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 23 December 2024.

Gogia, A. & Agarwal, P. Metabolic syndrome. Indian J. Med. Sci. 60(2), 72 (2006).

Suapumee, N., Seeherunwong, A., Wanitkun, N. & Chansatitporn, N. Examining determinants of control of metabolic syndrome among older adults with NCDs receiving service at NCD Plus clinics: Multilevel analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24(1), 1118 (2024).

Saklayen, M. G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 20(2), 1–8 (2018).

Organization WH. Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: healthy-lifestyle counselling. Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: Healthy-lifestyle counselling 2018.

Faijer-Westerink, H. J., Kengne, A. P., Meeks, K. A. & Agyemang, C. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 30(4), 547–565 (2020).

Adogu, P., Ubajaka, C., Emelumadu, O. & Alutu, C. Epidemiologic transition of diseases and health-related events in developing countries: A review. Am. J. Med. Med. Sci. 5(4), 150–157 (2015).

Ogunyemi, S. A. et al. Assessment of physical inactivity level, work-related stress, and cardiovascular disease risk among nigerian university staff members. J. Clin. Prev. Cardiol. 12(2), 66–73 (2023).

Alavi, S., Makarem, J., Mehrdad, R. & Abbasi, M. Metabolic syndrome: A common problem among office workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 6(1), 34 (2015).

Santana AI, das Merces MC, Magalhaes LB, Costa AL, D’Oliveira A. 2020 J. Association between metabolic syndrome and work: an integrative review of the literature. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Trabalho. 18(2) 185.

Manaf, M. et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its associated risk factors among staffs in a Malaysian public university. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–11 (2021).

Davila, E. P. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US workers. Diabetes Care 33(11), 2390–2395 (2010).

Geto, Z. et al. Cardiometabolic syndrome and associated factors among Ethiopian public servants, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 20635 (2021).

Amarasekara, P., de Silva, A., Swarnamali, H., Senarath, U. & Katulanda, P. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices on lifestyle and cardiovascular risk factors among metabolic syndrome patients in an urban tertiary care institute in Sri Lanka. Asia Pac. J. Pub. Health. 28, 32S-40S (2016).

Bogale, S. K., Sarma, H., Alamnia, T. T. & Kelly, M. Workplace-based education interventions for managing metabolic syndrome in low-and middle-income Countries: A realist review. Public Health Chall. 3(3), e224 (2024).

MoH E. National strategic plan for the prevention and control of major non-communicable diseases, 2013–2017 EFY (2020/21–2024/25). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2020.

Bogale, S. K., Sarma, H., Gray, D. & Kelly, M. The effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of an education intervention promoting healthy lifestyle to reduce risk factors for metabolic syndrome, among office workers in Ethiopia: A protocol for a randomized control trial study. PLoS ONE 19(8), e0307659 (2024).

Hopewell S, Chan A-W, Collins GS, Hróbjartsson A, Moher D, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. bmj 389 (2025).

Shitu, K. & Kassie, A. Behavioral and sociodemographic determinants of hypertension and its burden among bank employees in metropolitan cities of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Int. J. Hypertens. 2021(1), 6616473 (2021).

Tran, A. et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among working adults in Ethiopia. Int. J. Hypertens. 2011(1), 193719 (2011).

Dejenie, M., Kerie, S. & Reba, K. Undiagnosed hypertension and associated factors among bank workers in Bahir Dar City, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2020 a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16(5), e0252298 (2021).

Champion, V. L. & Skinner, C. S. The health belief model. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 4, 45–65 (2008).

Luszczynska, A. & Schwarzer, R. Social cognitive theory. Fac Health Sci. Publ. 2015, 225–251 (2015).

HEALTH FDROEMO. Guidelines on Clinical and Programmatic Management of Major Non Communicable Diseases. 2016.

Kassi, E., Pervanidou, P., Kaltsas, G. & Chrousos, G. Metabolic syndrome: Definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 9, 1–13 (2011).

Detection NCEPEPo, Adults ToHBCi. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): The Program; 2002.

Verma, A., Mehta, S., Mehta, A. & Patyal, A. Knowledge, attitude and practices toward health behavior and cardiovascular disease risk factors among the patients of metabolic syndrome in a teaching hospital in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care. 8(1), 178–183 (2019).

Cleghorn, C. L. et al. Can a dietary quality score derived from a short-form FFQ assess dietary quality in UK adult population surveys?. Public Health Nutr. 19(16), 2915–2923 (2016).

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 385–96 1983.

Singh, P. Sample size for experimental studies. J. Clin. Prev. Cardiol. 1(2), 88–93 (2012).

Sinaga M, Lindstrom D, Teshome MS, Yemane T, Tegene E, Belachew T. Effect of Behaviour Change Communication on Metabolic Syndrome and Its Markers among Ethiopian Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. 2020.

Wu P, Chang H, Wu T, Ding L, Van Duong T, Yang S-H. Work-Site Nutrition Education Decreases Metabolic Syndrome Factors. Austin J. Nutri. Food Sci. 8(2) 2020.

Boshtam, M. et al. Effects of 5-year interventions on cardiovascular risk factors of factories and offies employees of isfahan and najafabad: Worksite intervention project-isfahan healthy heart program. ARYA Atheroscler. 6(3), 94 (2010).

Ryu, H., Jung, J., Cho, J. & Chin, D. L. Program development and effectiveness of workplace health promotion program for preventing metabolic syndrome among office workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(8), 878 (2017).

Castro-Quezada, I. et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and dyslipidemia in adolescents from Chiapas, Mexico. Nutrients 16(10), 1483 (2024).

Lam, Y. Y. & Ravussin, E. Analysis of energy metabolism in humans: A review of methodologies. Mol. Metab. 5(11), 1057–1071 (2016).

Murakami, T. et al. Triglycerides are major determinants of cholesterol esterification/transfer and HDL remodeling in human plasma. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15(11), 1819–1828 (1995).

Farhana A, Rehman A. Metabolic consequences of weight reduction. 2021.

Fahed, G. et al. Metabolic syndrome: Updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(2), 786 (2022).

Santos, H. O. & Lavie, C. J. Weight loss and its influence on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations: A noble clinical hesitation. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 42, 90–92 (2021).

Vella, C. A., Kravitz, L. & Janot, J. M. A review of the impact of exercise on cholesterol levels. IDEA Health Fit. Sour. 19(10), 48–54 (2001).

Halloran JD. Attitude formation and change. 1967.

Reda, A. A., Moges, A., Wondmagegn, B. Y. & Biadgilign, S. Alcohol drinking patterns among high school students in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 12, 1–6 (2012).

Frone, M. R. Work stress and alcohol use. Alcohol Res. Health 23(4), 284 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the research participants, data collectors, intervention providers, and those who contributed to the development of the intervention. Additionally, we would like to thank the city health departments and bank managers at the selected sites for graciously allowing us to collect data from their employees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SKB and MK conceptualised the study. SKB, MK, HS, and DG, were responsible for the methodology and study design. SKB, MK, and HS were responsible for data validation. SKB conducted the formal data analysis. SKB conducted the investigation. SKB were responsible for financial resources, local staff resources, and laboratory equipment. SKB were responsible for data curation. SKB visualised the data. SKB wrote the original draft manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. MK, HS and DG supervised the study. MK was responsible for project administration. SKB and MK were responsible for funding acquisition. SKB had full access to and verified all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bogale, S.K., Sarma, H., Gray, D. et al. A healthy lifestyle education intervention for metabolic syndrome risk reduction among office workers in Ethiopia: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 39266 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22962-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22962-8