Abstract

Theoretical and anecdotal work suggests that Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) reactions go up and down during the day. However, empirical evidence supporting this claim is lacking. It is also unknown in which context PGD reactions go up and down. Using Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM), we examined whether PGD reactions (ESM-PGD) relate to contextual factors in daily life. For 14 days, five times per day, bereaved adults (N = 53; 74% women) rated the intensity of 11 ESM-PGD reactions representing DSM-5-TR PGD symptoms. Using mixed-effect regression analyses, we examined whether contextual factors (i.e., physical and social environments, and time of day) were associated with each ESM-PGD reaction separately. Being away from home compared to being at home was associated with more avoidance. Being alone compared to being in a pleasant social contact was associated with more preoccupation with the loss, intensified feelings that part of oneself died, and increased perception of the loss as unreal. Lastly, a later time of day was related to stronger feelings of loneliness and difficulties moving on. Our findings suggest that ESM-PGD reactions may be context-dependent. This calls for a context-sensitive treatment approach, such as ecological momentary interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) includes Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) as a diagnosis1. The prevalence rate of PGD is 3.3% based on a representative sample of bereaved people2. PGD is characterized by ten criteria: yearning, preoccupation, feeling that part of oneself died, perceiving the loss as unreal, avoidance, intense emotional pain (e.g., sadness, anger), difficulty moving on, numbness, meaninglessness of life, and loneliness. Importantly, the symptoms should cause significant impairment in functioning in daily life and should be present at least 12 months after loss.

Anecdotal and theoretical work suggests that grief advances non-linearly and oscillates moment to moment. For instance, people may experience “pangs” or “waves of grief”3,4. Current grief research is, however, dominated by cross-sectional research using retrospective self-report measures5,6,7,8, where participants report how frequently they had specific PGD reactions over the past month. This method inherently fails to capture possible changes in grief reactions in daily life. Capturing these changes in PGD reactions in daily life can provide novel insights in the phenomenology and etiology of PGD9. For instance, hearing a song on the radio may remind the bereaved person of the deceased, which may cause a wave of grief3,10,11.

One way to examine possible changes in PGD reactions in daily life is by using Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM)12,13,14. In ESM research, participants are usually asked to monitor their reactions as they occur in their natural environment, usually multiple times a day for an extended period. This method has many advantages. Examples of these advantages are 1) reducing recall bias, 2) capturing changes over time, and 3) examining micro-processes (e.g., how cognitive, behavioral, and affective reactions interact over short periods of time)13,15,16. Despite these advantages of ESM, research applying this method to study PGD reactions is lacking [cf.12,14,17,18].

The few available ESM studies on PGD show that asking people once (i.e., daily diary studies) or multiple times per day (i.e., ESM) about their PGD reactions is feasible and acceptable12,14,17,18. In addition, bereaved people reported on average lower PGD severity when assessed using ESM (ESM-PGD) compared to PGD severity assessed retrospectively12. This implies that PGD assessed retrospectively may overestimate symptom severity. Moreover, ESM-PGD reactions seem to fluctuate in the daily life of bereaved people18. Nevertheless, we do not know yet what contextual factors in daily life relate to fluctuations in ESM-PGD reactions. Examining these factors is relevant to better understand what facilitates, but also what hinders, people in coping with loss in daily life.

Capturing momentary contexts of symptoms is grounded in the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a treatment approach that among others strengthens self-monitoring techniques to monitor one’s own cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses in specific circumstances19. Once these connections between symptoms and the environment are understood, they can be used in interventions aimed at modifying the environment, altering the interpretation of the environment, or the interaction with the environment20. Several contextual factors might be relevant in relation to ESM-PGD reactions, a notion substantiated by the findings of research on grief triggers10,11. Moreover, according to contextual behavioral science and contemporary integrative interpersonal theory, how people feel, act, and think, depends on the context21,22, such as where you are (i.e., physical environment) and who you are with (i.e., social environment). It seems plausible that these two contextual factors affect ESM-PGD reactions in the daily lives of bereaved people.

Regarding the physical environment, drawing from literature in non-bereaved samples, being at home versus away from home resulted in a better cognitive performance, because people engaged in fewer cognitive tasks when being away from home23. Moreover, being at home compared to being at work was more frequently associated with low positive and negative arousal affect, whereas being at work was associated with high positive and negative arousal affect24. Applying this to bereaved people, being at home (vs. away from home) may trigger reminders of the loss (e.g., photographs, artifacts, music)10,11,25. Similarly, visiting places that were visited together with the deceased may also trigger these reminders10, potentially coinciding with stronger ESM-PGD reactions.

Regarding the social environment, prior ESM research in non-bereaved samples has shown that people who spend more time alone and find others’ company less pleasant exhibit higher levels of general psychopathology and depression26,27. Sad or unpleasant interactions may worsen mood, whereas positively charged interactions can elevate mood or serve as a distraction from distressing emotions28,29. Applying this to bereaved people, seeing other couples after losing a partner may trigger reminders of the loss10, however, the presence of others and pleasant interactions may also coincide with less intense ESM-PGD reactions.

Lastly, it seems plausible that time of day may relate to ESM-PGD reactions. For instance, reflecting at the end of the day on having spent the day without the deceased, or waking up in the morning and realizing once again that the deceased is not present, could both be associated with stronger ESM-PGD reactions. This is seemingly related to a previous finding about grief triggers. People who have experienced a loss often feel distraught when they are no longer distracted and have to deal with the loss directly10. Nevertheless, evidence regarding the possible associations between time of day and ESM-PGD reactions is lacking.

In sum, based on anecdotal, theoretical, and preliminary empirical work, ESM-PGD reactions seem to go up and down in the daily life of bereaved people3,10,11,12,18. However, it is yet unknown what contextual factors are related to these changes. It is likely that ESM-PGD severity differs in relation to the context, including the physical and social environment, as well as time of day. We are the first to explore to what extent contextual factors (i.e., physical and social environment, and time of day) relate to ESM-PGD reactions.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Dutch and German adults who have lost a partner, family member, or a friend at least three months earlier were eligible to participate in this study. For safety reasons, participants who were acutely suicidal or had a prior diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were excluded, as assessed at baseline. The ethics committee of the University of Twente approved this study (ID: 211101). This research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2013. All participants provided informed consent. After study completion, participants had a chance to take part in a raffle for a voucher of 50EUR. Social networking sites, word of mouth, and websites for bereaved people were used to recruit participants. Data collection spanned between January and March 2022.

This study is part of an ongoing project, “Grief-ID” which is focused on assessing and treating PGD in daily life12. The study consisted of three parts. First, a structured telephone interview (T1) lasting approximately 45 min was conducted by a trained master’s student in clinical psychology. The second part of this study included the ESM phase. During the ESM phase, participants completed a short survey, with a minimum of 15 items and a maximum of 17 items, five times per day for 2 weeks. A full list of these items can be found in Supplementary Table A. Notifications were sent to participants’ phones semi-randomly at the following intervals: 8.30–9.30 AM, 11.30 AM-12.30 PM, 2.30–3.30 PM, 5.30–6.30 PM, and 8.30–9.30 PM. Reminders, if needed, were sent 10 and 20 min after the initial notification. Participants had a 60 min time window to complete the survey; if it was not completed within 60 min, the entry was considered missing. If the participant missed three entries in a row, the interviewer contacted the participant and encouraged them to complete future entries. Participants were able to contact the research team if needed during study participation. Approximately two days after finishing the ESM phase, participants had a second structured telephone interview (T2). A detailed description of the study procedures is provided elsewhere12,30.

Measures

Baseline PGD levels (B-PGD)

At T1, the B-PGD severity was assessed using the 22-item Traumatic Grief Inventory-Clinician Administered (TGI-CA)31. An example item is: “In the past 2 weeks, did you feel bitterness or anger related to the death of [____]?” the frequency was rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The time frame was adapted to 2 weeks instead of past month for the purpose of this study (i.e., to match the 2-week time frame of the ESM phase). DSM-5-TR PGD symptom severity is represented by the sum score of 11 items (i.e., items 1–3, 6, 8–11, 18–19, and 21). Items 2 and 8 assessed the same PGD symptom (i.e., “intense emotional pain (e.g., anger, bitterness, sorrow)”). The highest score on items 2 and 8 was used to represent the “intense emotional pain” PGD symptom. The total B-PGD scores ranged from 10 to 50. A B-PGD score of ≥ 33 indicates probable PGD caseness32. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha level was 0.88.

ESM items assessing PGD reactions (ESM-PGD)

Prior work from our research group12,18 resulted in the development of eleven ESM-PGD items that match the 10 PGD symptoms as defined in the DSM-5-TR1. One DSM-5-TR PGD symptom (i.e., “Intense emotional pain (such as anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death.”) was assessed with two ESM-PGD items (i.e., “In the past 3 h, I felt sad about his/her death.” and “In the past 3 h, I felt bitter or angry about his/her death”). See Supplementary Table A for all items. Participants rated to what extent they experienced each of the 11 DSM-5-TR PGD reactions in the past 3 h on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much). The ESM-PGD items were developed and validated using cognitive interviewing. Details about the development of ESM-PGD items are described elsewhere12. In this study, the scale reliability Omega values were 0.85 at the within-, and 0.95 at the between-person level.

ESM items assessing contextual factors

The ESM items used to assess contextual factors in the current study were derived from prior research33. See Supplementary Table A for an overview. The first item was “Where were you?” which was dichotomized into being at home vs. away from home. The second item was “Who were you with?”; answers were dichotomized into alone vs. with others. If participants reported being with others, they were asked to rate how pleasant the contact was on a scale from 0 (very unpleasant) to 6 (very pleasant). Subsequently, three categories were constructed: “with others and the contact was pleasant,” “with others and the contact was less pleasant,” and “being alone”. The latter was used as a reference category in the analyses. The distinction between pleasant and less pleasant contact was based on the sample’s median rating (i.e., ≥ 5 was considered pleasant contact with others). This categorical variable with the three options was dummy-coded into “alone vs. others and pleasant contact” and “alone vs. others and less pleasant contact”. Lastly, we created a variable for time of day (based on the position of the entry during a day); this was treated as a continuous variable where 1 indicated the first timepoint of the day, and 5 was the latest timepoint of the day.

Statistical analyses

We excluded ESM data from day 14 from our analyses because of a technical error encountered on that day. More specifically, some people did not receive notifications to respond to the questions. The maximum number of possible observations was 65. Following prior ESM research34, participants who responded to fewer than 50% (< 33) of the measurements, including ESM-PGD reactions and contextual factors, were excluded. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to compare participants included in the analyses with those excluded. More specifically, we compared the two groups in terms of demographic and loss characteristics, namely age (in years), level of education (other than college/university vs. college/university), cause of death (natural vs. unnatural (e.g., accident)), kinship to the deceased (nuclear family member vs. other), and time since loss (in years).

Two-level mixed-effect regression models were used to examine the associations between contextual factors and ESM-PGD reactions. We calculated intraclass correlations (ICC) for each dependent variable (i.e., each ESM-PGD reaction). The multilevel analysis is justified if the ICC is higher than 0.0535. The ICC values for each dependent variable ranged between 0.58 and 0.91 (see Supplementary Table B), indicating that the ESM-PGD reaction ratings within people were strongly correlated. The independent variables were cluster-mean-centered, meaning that the person’s mean was subtracted from each value for a given contextual factor. This separates level-1 effects from level-2 effects36,37. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, each model included one contextual factor (i.e., being at home vs. away from home, being alone vs. with others and pleasant or less pleasant contact, or time of day) as independent variable and one ESM-PGD reaction as dependent variable. We applied the Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment method38 to correct for multiple comparisons, designed to reduce the Type-I error rate by ranking the p-values.

Data analyses were performed using R version 4.4.139 and the lme4 package40. The covariance structure was specified as unstructured and Satterthwaite degrees of freedom approximation available in lmerTest package was used41. The models included random effects for participants to account for variability in their intercepts (i.e., random intercepts) and statistical dependency of observations (level 1) nested within participants (level 2). We examined another higher-order level in which observations could be nested within days. However, the random variation of the day level was equal to zero. Therefore, the two-level structure was retained. In addition to random intercept models, we also estimated random intercept and random slope models. The addition of random slopes did not significantly improve the model fit as the values of AIC and BIC fit indices were lower for models without random slopes. Therefore, we retained the more parsimonious random intercept models.

Results

Characteristic of participants

In total, 53 out of 80 people completed 50% or more observations and were included in our analyses. The included participants (N = 53) did not differ from those excluded (N = 27) regarding background and loss-related characteristics (see Supplementary Table C). Table 1 describes the sample characteristics. The majority of the sample were women (74%), had college or university degrees (85%), had lost a nuclear family member (66%), and had experienced a loss due to natural death (e.g., illness) (89%), on average, 5.5 years earlier. Three participants met criteria for probable PGD.

The mean values of ESM-PGD reactions ranged between 0.33 and 0.87. The ESM-PGD item assessing avoidance had the lowest overall mean, whereas sadness had the highest mean (see Supplementary Table B). Concerning contextual factors, being at home was most frequently reported (65%). Participants reported being more frequently with one other person or multiple other people (60%) than being alone (40%). Table 2 presents the descriptive values for the response options for each contextual factor.

Associations between contextual factors and ESM-PGD reactions

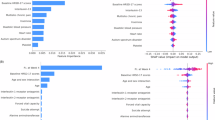

Table 3 describes parameter estimates for the two-level mixed-effects regression analyses for each ESM-PGD reaction. When participants were at home compared to being away from home, avoidance of places, things, or thoughts that reminded them of the deceased was lower. When participants were in pleasant contact with others compared to being alone, they were less preoccupied with thoughts or images about the deceased, felt less as though a part of themselves has died, and experienced less that the loss was unreal. Lastly, later in the day, participants experienced more difficulties in moving on and also felt lonelier because of the loss. None of the other contextual factors were significantly related to ESM-PGD reactions. In addition, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons, which rendered all p-values non-significant. Given the exploratory nature of the analyses, Table 3 presents the unadjusted p-values (i.e., prior to the Benjamin-Hochberg correction), alongside their 95% confidence intervals. The latter provide additional support of the significance of the findings.

Discussion

This study explored the associations between contextual factors and ESM-PGD reactions in the daily lives of bereaved people. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first ESM study exploring associations between contextual factors (i.e., the physical environment, social environment, and time of day) and ESM-PGD reactions in bereaved people, moving the field beyond retrospective PGD measurement12. A community sample of 53 Dutch- and German-speaking adults rated ESM-PGD reactions, based on the DSM-5-TR criteria, five times a day at semi-random time intervals for 14 consecutive days. We examined how ESM-PGD reactions vary depending on whether people are at home vs. away from home, in a pleasant or less pleasant social environment vs. alone, and during earlier vs. later time of day.

Our first main finding suggested that being away from home, compared to being at home, is associated with more avoidance of places, objects, or thoughts that remind the bereaved person that their loved one is deceased. A person may avoid loss-related stimuli out of fear that confrontation with these stimuli is unbearable42. It has repeatedly been found that avoidance contributes to more negative bereavement outcomes6,42. Our findings provide first insights into where this avoidance takes place. Being away from home and experiencing more avoidance of loss triggers may paradoxically refer to the assumption that one of the places that people avoid is home, and thus being at home is the place that reminds them the most that their loved one is dead, especially if the household was shared with the lost person and thus people may have more triggers such as shared pictures, places, or experiences at home10. On the other hand, at home, people may feel safe, and they can control what triggers they are confronted with (e.g. memorabilia such as pictures of the deceased). However, being away from home can potentially confront them with uncontrollable loss triggers (e.g., places where they used to go with the deceased)10, which may coincide with more avoidance. Nevertheless, future research is needed to examine which specific places, objects, and thoughts bereaved people tend to avoid. This information seems useful for balanced exposure to loss-related stimuli, which can occur both at home and in other environments.

Our second main finding was that the social environment was positively related to three ESM-PGD reactions. Compared to being with others and engaging in pleasant contact, being alone was related to more preoccupation with thoughts and images of the deceased, stronger feelings as if a part of themselves has died, and more intense experiences that the loss feels unreal. No significant differences in intensity of ESM-PGD reactions were found when being with others but in less pleasant contact compared with being alone. This may suggest that for social contact to have potential buffering effects on PGD, it needs to be appraised as pleasant22,27. Similar results were found in prior ESM studies examining associations between social interactions and depression in non-bereaved samples. These studies found that more pleasant social situations improved mood, while unpleasant social situations were related to increases in depressed mood28. It is likely that pleasant social contacts may indicate a better quality of one’s social support system, which has shown to be related to reduced PGD severity in cross-sectional research43. Social interactions may also serve as a positive distraction from grief44. For instance, being in social contact may distract people from getting stuck in rumination, which has been shown to play an important role in the persistence of PGD6. Rumination has also been associated with increased negative affect and decreased positive affect in bereaved people in a daily diary study45. Furthermore, the type of relationship someone has with the person they spend the most time with during the day may highlight the supportive role of family compared to more distant relationships, such as those with colleagues. However, family members may also serve as a less effective distraction, as the loss is more likely to be frequently reflected upon, unlike in more distant relationships. Future studies could explore the associations between pleasantness of social interactions and PGD reactions in greater detail, considering the type and quality of the relationship as possible moderators.

Our third main finding was that later in the day people reported more intense ESM-PGD reactions. Later timing of the day was positively related to difficulties moving on and more feelings of loneliness. At least two reasons might explain this finding. First, at the end of the day, people may have more time and fewer distractions from their daily routines, allowing them to grieve more and reflect on the impact of the loss10. Second, there is less daylight at the end of the day. Findings from earlier ESM research suggest that less daylight is associated with higher stress levels46. Therefore, our findings expand the literature on grief triggers by highlighting that contextual factors in a person’s environment can play a critical role in shaping grief reactions in daily life10,11.

Several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. First, the current sample was a self-selected sample of general bereaved people. As a result, only three participants met criteria for probable PGD and mean levels of ESM-PGD reactions were relatively low. Our findings may therefore not generalize to people with a PGD diagnosis. Although our sample size of 53 people may appear modest, it exceeds the median of 19 participants reported in a systematic review of 110 ESM studies47. Additionally, each participant completed up to 65 measurement points, resulting in a substantial number of data points which underscores our sample size adequacy for within-person analyses. This is consistent with the average of 60 measurements per person reported in a meta-analysis of 79 ESM studies48. Nonetheless, the sample size limited our ability to conduct between-person analyses, such as comparisons based on participant and loss related characteristics49.

Second, the participants in our study experienced the loss on average five and a half years earlier. It is plausible that contextual factors, such as social support, play a more prominent role in the acute grief phase after loss, as the presence of supportive others can offer comfort, stability, and validation, potentially buffering the long-term impact of loss50. While our findings suggest that contextual factors are linked to grief intensity even years after a loss, their impact is likely to be more pronounced among more recently bereaved people. In addition, our sample included mostly people whose loved one died due to natural circumstances, which may explain why only three participants met criteria for probable PGD at baseline. Consequently, our results may not generalize to individuals who are more recently or traumatically bereaved.

Third, due to lack of prior ESM-PGD research, we did not have a priori hypotheses about the associations between contextual factors and ESM-PGD reactions. Therefore, we conducted an exploratory study including multiple tests, which may have increased the risk of Type I errors. To explore this further, we performed post-hoc corrections for multiple comparisons, using the Benjamini–Hochberg method which rendered all associations non-significant. It is possible that this correction was overly conservative, potentially increasing the risk of Type II errors. For this reason, we retained the non-corrected p-values. Relatedly, there is ongoing debate in the scientific literature about the necessity of p-value adjustments in exploratory analyses. In the multilevel models used in this study, this concern is likely mitigated through partial pooling51. Future studies may consider Bayesian statistics as an alternative approach to estimate the probability of an effect rather than classifying the results as significant or not51. Therefore, more ESM research on contextual factors and PGD is needed to further establish their potential relationships.

Despite these limitations, this exploratory study has potential implications for clinical practice and research. Our findings suggest that being with others and in pleasant social contact, being away from home and an earlier time of day could tentatively be regarded as protective factors for PGD, whereas being at home, alone, or later hours of the day may represent risk factors. From a clinical perspective, these findings align with the principles of CBT in grief treatment, highlighting the potential benefits of fostering social engagement and supporting a person’s reintegration into daily life after loss, for instance, through behavioral activation52,53. To further expand upon these findings, future research could explore the clinical utility of Ecological Momentary Interventions (EMI) to treat PGD in daily life, which offer new avenues for treatment delivery and accessibility54. Further examination of contextual factors in the daily lives of people with PGD may provide valuable new insights into implementing context- and time-sensitive treatment strategies. Ultimately, ESM can potentially ameliorate and advance personalized health care by providing interventions in a timely manner and in the natural environment of the bereaved.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study are available in the Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS) repository.

Reference to the dataset: L.I.M, Lenferink; M. Franzen, 2025, "Dataset on grief in daily life in a community sample", https://doi.org/10.17026/SS/INSTAE, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed.) Text Revision. (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022).

Rosner, R., Comtesse, H., Vogel, A. & Doering, B. K. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 287, 301–307 (2021).

Arizmendi, B. J. & O’Connor, M.-F. What is “normal” in grief?. Aust. Crit. Care 28, 58–62 (2015).

Stroebe, M. & Schut, H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 23, 197–224 (1999).

Eisma, M. C., Bernemann, K., Aehlig, L., Janshen, A. & Doering, B. K. Adult attachment and prolonged grief: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 214, 112315 (2023).

Eisma, M. C. & Stroebe, M. S. Emotion regulatory strategies in complicated grief: A systematic review. Behav. Ther. 52, 234–249 (2021).

Lancel, M., Stroebe, M. & Eisma, M. C. Sleep disturbances in bereavement: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 53, 101331 (2020).

Lobb, E. A. et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 34, 673–698 (2010).

Reis, H. T. Why researchers should think ‘real-world’: A conceptual rationale. in Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (eds. Mehl, M. R. & Conner, T. S.) 3–21 (The Guilford Press, 2012).

Smith, K. V., Rankin, H. & Ehlers, A. A qualitative analysis of loss-related memories after cancer loss: a comparison of bereaved people with and without prolonged grief disorder. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 11, 1789325 (2020).

Wilson, D. M., Underwood, L. & Errasti-Ibarrondo, B. A scoping research literature review to map the evidence on grief triggers. Soc. Sci. Med. 282, 114109 (2021).

Lenferink, L. I. M., van Eersel, J. H. W. & Franzen, M. Is it acceptable and feasible to measure prolonged grief disorder symptoms in daily life using experience sampling methodology?. Compr. Psychiatry 119, 152351 (2022).

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A. & Hufford, M. R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 1–32 (2008).

Mintz, E. H. et al. Ecological momentary assessment in prolonged grief research: Feasibility, acceptability, and measurement reactivity. Death Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2024.2433109 (2024).

Myin-Germeys, I. et al. Experience sampling methodology in mental health research: new insights and technical developments. World Psychiatry 17, 123–132 (2018).

Myin-Germeys, I. & Kuppens, P. The open handbook of experience sampling methodology: a step-by-step guide to designing, conducting, and analyzing ESM studies (Center for Research on Experience Sampling and Ambulatory Methods Leuven, 2022).

Aeschlimann, A., Gordillo, N., Ueno, T., Maercker, A. & Killikelly, C. Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile app for prolonged grief disorder symptoms. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 6, 1–23 (2024).

Lenferink, L. I. M. et al. Fluctuations of prolonged grief disorder reactions in the daily life of bereaved people: an experience sampling study. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06987-2 (2024).

Dudley, R., Kuyken, W. & Padesky, C. A. Disorder specific and trans-diagnostic case conceptualisation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 213–224 (2011).

Von Klipstein, L. et al. Opening the contextual black box: A case for idiographic experience sampling of context for clinical applications. Qual. Life Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03848-0 (2024).

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D. & Wilson, K. G. Contextual behavioral science: creating a science more adequate to the challenge of the human condition. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 1, 1–16 (2012).

Pincus, A. L. A Contemporary integrative interpersonal theory of personality disorders. in Major theories of personality disorder (eds. Lenzenweger, M. F. & Clarkin, J. F.) 282–331 (The Guilford Press, 2005).

Verhagen, S. J. W. et al. Measuring within-day cognitive performance using the experience sampling method: A pilot study in a healthy population. PLoS ONE 14, e0226409 (2019).

Sandstrom, G. M., Lathia, N., Mascolo, C. & Rentfrow, P. J. Putting mood in context: Using smartphones to examine how people feel in different locations. J. Res. Personal. 69, 96–101 (2017).

DeGroot, J. M. & Carmack, H. J. Accidental and Purposeful Triggers of Post-Relationship Grief. J. Loss Trauma 28, 391–403 (2023).

Achterhof, R. et al. General psychopathology and its social correlates in the daily lives of youth. J. Affect. Disord. 309, 428–436 (2022).

Snippe, E. et al. Change in daily life behaviors and depression: Within-person and between-person associations. Health Psychol. 35, 433–441 (2016).

Pemberton, R. & Fuller Tyszkiewicz, M. D. Factors contributing to depressive mood states in everyday life: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 200, 103–110 (2016).

van Winkel, M. et al. Unraveling the role of loneliness in depression: The relationship between daily life experience and behavior. Psychiatry 80, 104–117 (2017).

Pociūnaitė-Ott, J. & Lenferink, L. I. A FAIR intensive longitudinal data archive on prolonged grief in daily life. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 16(1), 2526885 (2025).

Lenferink, L. I. M. et al. The traumatic grief inventory-clinician administered: A psychometric evaluation of a new interview for ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR prolonged grief disorder severity and probable caseness. J. Affect. Disord. 330, 188–197 (2023).

Lenferink, L. I. M., Eisma, M. C., Smid, G. E., de Keijser, J. & Boelen, P. A. Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder: The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Compr. Psychiatry 112, 152281 (2022).

Franzen, M. Bullying victimisation through an Interpersonal Lens: Focussing on social interactions and risk for depression: (University of Groningen, 2022).

Kraiss, J. T., Kohlhoff, M. & Ten Klooster, P. M. Disentangling between- and within-person associations of psychological distress and mental well-being: An experience sampling study examining the dual continua model of mental health among university students. Curr. Psychol. 42, 16789–16800 (2023).

Peugh, J. L. A practical guide to multilevel modeling. J. Sch. Psychol. 48, 85–112 (2010).

Curran, P. J. & Bauer, D. J. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62, 583–619 (2011).

Yaremych, H. E., Preacher, K. J. & Hedeker, D. Centering categorical predictors in multilevel models: Best practices and interpretation. Psychol. Methods 28, 613–630 (2023).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2024).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 7(67), 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A. & Brockhoff, P. B. Christensen RH. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Boelen, P. A., Hout, M. A. V. D. & Bout, J. V. D. A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 13, 109–128 (2006).

Cacciatore, J., Thieleman, K., Fretts, R. & Jackson, L. B. What is good grief support? Exploring the actors and actions in social support after traumatic grief. PLoS ONE 16, e0252324 (2021).

Smith, K. V., Wild, J. & Ehlers, A. The masking of mourning: social disconnection after bereavement and its role in psychological distress. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 464–476 (2020).

Eisma, M. C., Franzen, M., Paauw, M., Bleeker, A. & Aan Het Rot, M. (2022) Rumination, worry and negative and positive affect in prolonged grief: A daily diary study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 29, 299–312.

Beute, F. & de Kort, Y. A. W. The natural context of wellbeing: Ecological momentary assessment of the influence of nature and daylight on affect and stress for individuals with depression levels varying from none to clinical. Health Place 49, 7–18 (2018).

Van Berkel, N., Ferreira, D. & Kostakos, V. The experience sampling method on mobile devices. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR). 50(6), 1–40 (2017).

Vachon, H., Viechtbauer, W., Rintala, A. & Myin-Germeys, I. Compliance and retention with the experience sampling method over the continuum of severe mental disorders: Meta-analysis and recommendations. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e14475 (2019).

Buur, C. et al. Risk factors for prolonged grief symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 107, 102375 (2024).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357 (1985).

Gelman, A., Hill, J. & Yajima, M. Why we (Usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 5, 189–211 (2012).

Rosner, R. et al. Grief-specific cognitive behavioral therapy vs present-centered therapy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 82, 109–117 (2025).

Smid, G. E. et al. Brief eclectic psychotherapy for traumatic grief (BEP-TG): Toward integrated treatment of symptoms related to traumatic loss. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 6, 27324 (2015).

Schueller, S. M., Aguilera, A. & Mohr, D. C. Ecological momentary interventions for depression and anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 34, 540–545 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andreea Pana, Bente Lauxen, Giulia Micheli, Hanneke Bos, Hans van Essen, Lara Urban, Michelle Todorovic, Sophie Becker, and Tom van Die for their support in recruiting participants and collecting the interview-data.

Funding

This publication is part of the project “Toward personalized bereavement care: Examining individual differences in response to grief treatment” [ID: Vl.Veni.211G.065] of the research programme [NWO Talent Programme 2021—Veni] which is financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and awarded to Lonneke I.M. Lenferink. JPO was financially supported by Trauma Data Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL conceptualized the study and was responsible for project administration, project supervision, and funding acquisition. L.L., M.F., and J.E. were responsible for data curation. J.P.O., J.K., and LL were responsible for data-analyses. J.P.O. wrote the original draft under supervision of LL. All authors have edited versions of the draft of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pociūnaitė-Ott, J., Kraiss, J., van Eersel, J.H.W. et al. An experience sampling study exploring associations between contextual factors and prolonged grief reactions in daily life. Sci Rep 15, 39410 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23122-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23122-8