Abstract

This paper evaluates the effectiveness of large language models (LLMs) in extracting complex information from text data. Using a corpus of Spanish news articles, we compare how accurately various LLMs and outsourced human coders reproduce expert annotations on five natural language processing tasks, ranging from named entity recognition to identifying nuanced political criticism in news articles. We find that LLMs consistently outperform outsourced human coders, particularly in tasks requiring deep contextual understanding. These findings suggest that current LLM technology offers researchers without programming expertise a cost-effective alternative for sophisticated text analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Text data has become increasingly relevant in social and behavioral sciences research1,2, enabling the study of phenomena that are challenging to capture using traditional structured, tabular data3. However, while analyzing large volumes of text holds significant potential, processing such data at scale presents considerable challenges2. In response, researchers have developed several approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

A first approach involves human readers manually coding text content. Within this framework, researchers typically consider two alternatives. One alternative is to employ highly skilled annotators, whose work can produce annotations of exceptional quality and is often regarded as the gold standard4. However, this strategy quickly becomes impractical for large-scale corpora due to the substantial time and financial costs it entails5,6. Another alternative is to outsource coding tasks to a large number of less specialized annotators, often through crowdsourcing. While this significantly reduces costs and turnaround time, it typically results in noisier and less consistent labels compared to expert annotation7,8,9.

A second approach involves dictionary-based methods, which analyze text by counting the frequency of words drawn from predefined lexical categories10,11,12. While substantially more scalable than manual annotation, these methods often lack the accuracy of human-coded data and frequently require manual validation of results13,14. Moreover, the effectiveness of these approaches is typically restricted to straightforward natural language processing (NLP) tasks, such as categorizing the sentiment of a text or determining whether it covers a particular topic—cases where predefined word categories may align well with the concepts being measured. Alternatively, a third approach relies on supervised machine learning (SML) methods—that is, models trained on data that have been manually labeled with the correct answers, such as BERT-like models15. This approach overcomes many of the limitations of dictionary methods and can perform more complex linguistic tasks, but it introduces two important drawbacks: these models generally require a high level of coding proficiency and they depend on manually annotated training data16. Importantly, if multiple NLP tasks are to be performed, separate labeled datasets must be created and distinct models trained for each task, creating substantial barriers for social and behavioral scientists.

With the recent development of generative large language models (LLMs) used as zero-shot learners, a novel way of approaching text analysis has emerged17. LLMs are a form of generative artificial intelligence (AI), based on deep neural networks trained on vast text corpora. These models are capable of generating, interpreting, and reasoning over natural language. In the context of NLP, zero-shot learning refers to a model’s ability to perform tasks for which it has received no explicit training, relying entirely on broad pre-trained knowledge rather than task-specific examples. This capability allows LLMs to generalize across a wide range of linguistic contexts without the need for fine-tuning on curated datasets for each new task18—a key limitation of traditional SML approaches.

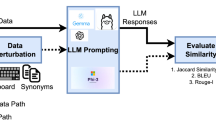

Building on these developments, this study evaluates the potential of LLMs as a substitute for outsourced human coders in applied social science research. Our evaluation is based on a corpus of 210 Spanish-language news articles, randomly sampled from the articles analyzed in19, which document a nationwide fiscal consolidation program affecting over 3,000 Spanish municipalities. Each article was first annotated by expert coders through a careful, deliberative process to produce gold standard labels for five tasks requiring deep semantic and contextual understanding: (T1) listing all municipalities mentioned in the article; (T2) indicating the total number of municipalities mentioned; (T3) determining whether the article contains criticism of municipal performance; (T4) identifying the source of the criticism, if any; and (T5) identifying the specific target of the criticism, if any (see Section "High-skill coders (gold standard labels)"). We then benchmarked the performance of two alternative annotation strategies—generative LLMs and outsourced human coders—against these expert labels. For the LLMs, we submitted zero-shot API prompts to four models—GPT-3.5-turbo, GPT-4-turbo, Claude 3 Opus, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet—tasking each with completing the five annotation tasks. For the human coders, we recruited students from a Spanish university to perform the same tasks in an incentivized online study. Finally, we assessed how closely the outputs from both LLMs and outsourced coders aligned with the expert annotations, enabling a comprehensive comparison of machine and outsourced human performance on complex text analysis tasks.

Results reveal a substantial performance gap between LLMs and outsourced human coders in their ability to replicate our set of gold standard labels. Although outsourced human coders performed significantly above chance across all tasks, LLMs consistently outperformed them on every metric. This advantage is so marked that LLMs achieve better results on complex, lengthy articles than outsourced annotators do on simpler, shorter ones (see Section "High-skill coders (gold standard labels)" for details on our criteria for classifying an article as “difficult” for a given task). Notably, even when restricting the comparison to outsourced annotators whose competence is above the median—representing our “best” outsourced annotators—LLMs continue to outperform them. These performance gains are especially marked for the most advanced LLMs, which achieve higher accuracy than earlier models, suggesting that further improvements may yield even more accurate and nuanced text analysis capabilities. Moreover, we find that LLM outputs exhibit considerably higher internal consistency compared to those of outsourced annotators.

Our findings indicate that generative LLMs, used in a zero-shot setting, represent a strong alternative to outsourced coders for extracting complex information from text data. Importantly, their strong performance is achieved through simple API calls, without the need for advanced coding skills or manually labeled training data. As such, LLMs constitute a powerful tool for researchers, opening new possibilities for large-scale and nuanced text analysis.

Related work

In recent years, the growing availability and diversity of text data have enabled researchers to explore an unprecedented range of topics. For instance, social media content has been analyzed to study emotional contagion20, inflation expectations21, and various aspects of electoral behavior and political polarization22,23. Building on the narrative approach pioneered by24, researchers have leveraged central bank communications and government statements to conduct causal analyses within macroeconomic general equilibrium models25,26,27. Legislative records, such as floor speeches and committee hearings, have been analyzed to understand political processes28,29,30, while media content, including movie scripts and subtitles, has been used to study social phenomena like gender stereotypes31,32,33,34.

Among the various sources of textual data, news articles have attracted particular attention in the social sciences, serving both as subjects of analysis35,36 and as instruments for understanding broader social and political phenomena. News content has been employed to evaluate policy impacts37,38, investigate the effects of bank runs39, understand how expectations influence diverse outcomes40,41, and enhance economic forecasting42. Prior research has also shown that media coverage can influence political outcomes and government decision-making43,44, as well as improve the predictability of stock market prices45,46. Given their richness and complexity—which often require nuanced and context-sensitive interpretation—in this study we use news articles to benchmark the performance of both LLMs and outsourced human coders on challenging NLP tasks (see Section "News articles sample").

This paper contributes to the growing literature evaluating the capabilities of LLMs across diverse tasks47,48,49. Within this broader context, an increasingly active line of research benchmarks LLMs against human annotators on NLP tasks, assessing their performance across domains, languages, and task types. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of recent studies in this area, highlighting the diversity of applications, model configurations, and types of human baselines.

As shown in Table 1, the study most closely aligned with ours is16, which evaluates GPT-3.5-turbo on English-language content moderation tasks involving tweets and short news excerpts. The authors find that the model outperforms crowd workers by approximately 25 percentage points across several classification categories, with substantially higher inter-coder agreement and a per-annotation cost roughly thirty times lower. Several subsequent studies listed in Table 1 confirm that frontier LLMs can rival or exceed human performance in tasks such as sentiment analysis, stance detection, political affiliation classification, and medical annotation.

Our study expands the scope of this emerging literature along five important dimensions. First, we evaluate a broader range of NLP tasks, including named-entity recognition (NER), entity counting, and identification of nuanced relationships between entities. This structured extraction tasks have not been systematically benchmarked against human coders in prior LLM evaluations. Second, we focus on problems that require extensive contextual and domain-specific knowledge. For example, determining whether an article criticizes the municipal government of Barcelona (T3) may involve distinguishing between references to the city government (Ajuntament) and the provincial administration (Diputació). This distinction often requires identifying the political actors that are mentioned, or having knowledge of who has certain institutional responsibilities. Third, unlike most studies in Table 1, which rely on short-form content such as tweets or snippets, our benchmark is based on full-length news articles. This introduces additional challenges related to document structure, discourse coherence, and long-range dependencies. Fourth, our corpus adds both linguistic and topical diversity by focusing on Spanish-language texts related to fiscal policy—an underrepresented setting in existing benchmarks, which primarily analyze English-language content. Finally, we adopt a more rigorous human baseline by comparing LLM outputs to annotations provided by context-aware, well-educated, incentivized coders, rather than relying on anonymous crowdsourced workers. Together, these contributions allow our study to complement and extend the growing body of work evaluating LLMs in applied social science settings.

Materials and methods

News articles sample

News articles provide an ideal document type for benchmarking LLM performance on complex text analysis tasks. They are typically information-rich, substantial in length, and often require contextual and domain-specific knowledge for accurate interpretation. In this study, we analyze a subset of articles from the corpus compiled by19, focusing on news reports that reference Spanish municipalities and the Supplier Payment Program. Launched by the Spanish government in 2012, this program sought to address the severe municipal arrears that had accumulated following the 2008–2009 financial crisis. During this period, local and regional governments amassed billions of euros in unpaid debts to private suppliers. The program enabled more than 130,000 affected firms to receive payment—via the state-owned Official Credit Institute—for outstanding invoices issued before 2012, ultimately covering over €30 billion in arrears.

The corpus compiled by19 comprises 24,134 articles retrieved from Factiva, an international news database produced by Dow Jones that aggregates content from over 30,000 sources across more than 200 countries. The retrieval filters selected articles written in Spanish or Catalan, published between 2011 and 2013, that referenced both Spanish municipalities and the Supplier Payment Program. For each article, Factiva provides its title, a snippet (a brief extract or summary of the article’s content), and its main text. For further details on the selection process, refer to Appendix A.1.

For the current study, we sampled 210 Spanish-written news articles from the19 corpus. Before drawing our sample of 210 articles, we excluded 330 articles that exceeded GPT-3.5-turbo’s maximum token limit of 4,097 tokens. This threshold affected only 1.5% of the articles from the original sample. Additionally, we removed 53 articles for which GPT-3.5-turbo encountered an error (typically a timeout) during the analysis conducted by the authors in19. If a sampled article was written in Catalan, classified as a commentary, or deemed excessively short, it was replaced in our study through resampling. Our final sample represents approximately 1% of the articles considered in19 and constitutes a sample size manageable for annotation by human coders. In Appendix A.2 , we provide one article as an example. The average article length in our subsample is 508.14 words, with the \(10^{\text {th}}\), \(50^{\text {th}}\), and \(90^{\text {th}}\) percentiles being 185.7, 478, and 887.3 words respectively.

Tasks description

In this article, we analyze the same five tasks introduced in19, which we briefly summarize below (see Appendix B.1 for detailed descriptions):

-

T1: List the names of all the municipalities mentioned in the article.

-

T2: Indicate how many municipalities are mentioned.

-

T3: Specify whether the municipal government is criticized in the article.

-

T4: If any criticisms are present, specify their source by selecting from a predefined list of seven options (plus a “not sure” option).

-

T5: If any criticisms are present, specify their target by selecting from a predefined list of eight options (plus a “not sure” option).

Note that each successive task involves increasing complexity and demands greater contextual knowledge for accurate completion. The first two tasks are closely related: T1 requires identifying municipalities mentioned in the text—a form of NER—while T2 involves counting these identified municipalities (entity counting). T3 requires not only understanding the text but also forming a judgment about its content. Since it involves a simple “yes” or “no” response, it can be interpreted as a binary classification task in the broader context of NLP.

T4 and T5 represent the most complex tasks in our framework, as they require inferring both the source and the target of criticisms, when present. Notably, an article may mention only the name of the individual issuing the criticism, and determining, for instance, whether it originates from the opposition requires recognizing that the individual belongs to a party opposing the one being criticized—an inference that depends heavily on contextual and domain-specific knowledge. These tasks are also distinctive in allowing for multiple correct responses: an article may feature criticisms from several actors, making more than one option valid. For example, in T4, a councilor from the ruling party may be issuing the criticism and be named with their party affiliation explicitly stated, in which case option 2 is correct and must be accompanied by either option 4 or option 5 (see Appendix B.1). In NLP, such problems are typically treated as multi-label classification tasks, where a single document may be assigned multiple labels. Section "Performance metrics" details the performance metrics used to evaluate tagging accuracy across all tasks.

Coding strategies

In this section, we outline the methods used to carry out the tasks described above. This study complies with all ethical and informed consent requirements. It received full approval from the ESADE Research Ethics Committee due to the involvement of human subjects. All research involving human participants was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

High-skill coders (gold standard labels)

To benchmark the performance of LLMs and outsourced human coders on the tasks described above, we first construct a set of annotations to serve as our gold standard. Following the recommendations of4, we define these gold standard labels as those produced by highly skilled coders. Throughout the coding process, we implemented rigorous quality assurance procedures to ensure consistency and reliability, as described in detail below.

First, all authors collaboratively reviewed each task and reached consensus on what should be considered the correct answer. All authors hold graduate or postgraduate training in topics relevant to the articles, and two were born and raised in Spain, providing strong contextual knowledge of the linguistic and political setting. Second, one author carefully read all 210 news articles and completed all five tasks for each article, generating an initial set of annotations. Third, each article—along with its initial annotations—was independently reviewed either by a trained research assistant (RA) or by a second author. To ensure reliability, more complex articles were deliberately assigned to authors rather than the RA. Fourth, the assigned reviewer read the article in full and independently completed the same set of tasks. In most cases, the second round of annotations confirmed the original responses, which were then retained as final. However, in cases where the two coders disagreed, additional authors reviewed the article and deliberated until consensus was reached—either confirming the original label or establishing a new one.

Inter-coder agreement—measured as the percentage of exact matches between the second tagger and the initial tagging—was consistently high across all tasks: 83.8% for T1, 81.9% for T2, 91.4% for T3, and 84.3% for both T4 and T5. For T4 and T5, agreement dropped to 72.7% when considering only articles where the municipal government was criticized (i.e., when T3 was coded as “yes”), suggesting these tasks were more challenging than the first three. Nevertheless, all results exceeded the 70% agreement threshold commonly considered acceptable in the literature56, indicating that the initial tagging already met satisfactory quality standards. Appendix B.2 provides descriptive statistics of the final answers for each task.

LLMs as coders

To assess the performance of LLMs on the proposed tasks, we employed several state-of-the-art commercial models from two leading companies in the field. Specifically, we used two models developed by OpenAI and two by Anthropic. From OpenAI, we included GPT-3.5-turbo, which powered the free tier of ChatGPT at the time of our analysis, and GPT-4-turbo, the company’s most advanced model at that time. From Anthropic, we used Claude 3 Opus and Claude 3.5 Sonnet—the two highest-performing models the company offered during our evaluation period—with the latter considered the more capable of the two.

For each model, we issued two independent API calls per news article, resulting in a total of 1,680 calls (210 news articles \(\times\) 4 models \(\times\) 2 calls per article per model). In each call, the model was asked to complete all five tasks using a standardized prompt. In addition to this task-specific prompt in Spanish, the LLMs were also provided with the following system prompt: “Usted es un asistente de investigación.” (English translation: “You are a research assistant”). A system prompt is an instruction that sets the model’s general behavior or persona throughout the session, independently of the specific task. Below, we provide an English translation of the task-specific prompt (the original Spanish version is available in Appendix B.3). During each call, the article under analysis was embedded within \(<\texttt {News}>\) and \(<\texttt {/News}>\) tags. All API calls were made with the “temperature” parameter set to 0 to encourage deterministic behavior. Because this setting does not fully eliminate variability57,58, we assess and compare each model’s internal consistency across repeated trials (see Section "Internal consistency").

Your task is to read a news article and answer questions about its content.

Provide your answer as a Python dictionary structured as follows:

\(\{\texttt { Q1: answer\,to\,question\,1, Q2: answer\,to\,question\,2, ...}\}\)

Do not add any additional explanation to your answer.

Do not leave any question unanswered.

\(<\texttt {News}>\) HERE THE NEWS IS INSERTED \(</\texttt {News}>\)

Q1: List all municipality names mentioned in the news, separated by a comma. If no municipality is mentioned, answer ’0’. If you are unsure, answer ’99’.

Q2: How many municipality names are mentioned in the news? If you are unsure, answer ’99’.

Q3: In this news, is the municipal management criticised? If the answer is yes, respond with ’1’. If the answer is no, respond with ’0’. If you are unsure, respond with ’99’.

Q4: In this news, who issues the criticism? Please select one of the following alternatives: If the criticism was made by an opposition councillor, answer ’1’. If the criticism was made by a councillor from the governing party, answer ’2’. If the criticism was made by the mayor, answer ’3’. If the criticism was made by the Partido Popular (PP), answer ’4’. If the criticism was made by the Partido Socialista (PSOE), answer ’5’. If there is no criticism of the municipal management, answer ’0’. If your answer does not fit into any of the above categories, answer ’98’. If you are unsure, answer ’99’.

Q5: In this news, who is the target of the criticism? Please select one of the following alternatives: If the current municipal government is criticised, answer ’1’. If the previous municipal government is criticised, answer ’2’. If the national government is criticised, answer ’3’. If the municipal opposition is criticised, answer ’4’. If the Partido Popular (PP) is criticised, answer ’5’. If the Partido Socialista (PSOE) is criticised, answer ’6’. If there is no criticism, answer ’0’. If your answer does not fit into any of the above categories, answer ’98’. If you are unsure, answer ’99’.

We spent US$0.20 to obtain all answers from GPT-3.5 (April 2024), US$3.46 from GPT-4 (April 2024), US$8.53 from Claude 3 Opus (June 2024), and US$2.28 from Claude 3.5 Sonnet (July 2024). In each case, the full set of responses was returned within minutes. For comparison,19 processed nearly 22,000 news articles in under two days using GPT-3.5-turbo at a total cost of US$96 (October 2023).

Importantly, for tasks T4 and T5—which may have multiple valid answers—we instructed the LLMs to provide a single response encoded as an integer. This design choice was motivated by both conceptual and practical considerations. Conceptually, it aligns with the objective in19, where the goal was to determine whether the source or target of criticism was affiliated with the ruling or opposition party in the specific municipality mentioned in the article. In that setting, identifying the politically relevant actor by one of its tags was sufficient for downstream classification (e.g., in a municipality ruled by PSOE, either knowing that it was from PSOE or that it was from the municipal government was enough). Practically, our preliminary experiments showed that LLMs generated more accurate and syntactically valid outputs—with fewer formatting errors and greater consistency—when restricted to producing a single answer, rather than a full set of labels. Models were also more likely to follow the prompt structure correctly and less likely to fail in returning a valid Python dictionary under this constraint (prompt sensitivity is further analyzed in Section "Prompt sensitivity").

Outsourced human coders

To evaluate the performance of LLMs against more traditional, less scalable, and typically more expensive alternatives, we conducted an online study involving human coders. Participants were students from ESADE, a Spanish university located in Barcelona, Catalonia, who collectively completed the same set of 210 news articles. This approach—commonly referred to as crowdsourcing, in which input is collected from a distributed group of individuals, often via online platforms—has been validated in prior research as a reliable method for text annotation59.

Students completed the study online using Qualtrics, a web-based software platform for creating surveys and collecting data. Each participant was asked to read three news articles and to complete the five associated tasks while reading each of them. To maintain parallelism with what we requested from the LLMs, Qualtrics only allowed a single answer for T4 and T5.

Our initial goal was to have each article read by two students, targeting a total of 140 participants. Recruitment was conducted via an open online platform accessible to all ESADE students, with participants receiving course credit for their involvement (see Appendix Figure D1). To ensure response quality and reliability, the questionnaire included two attention check questions with clear, correct answers, explicitly communicated to students60. At the start of the survey, students were informed that failing these checks could result in no course credit. Additionally, per ESADE’s course credit policy, students understood that incomplete participation (i.e., not answering all three news articles) would also forfeit credit. This approach incentivized participants to complete all tasks accurately.

If a participant failed an attention check or did not complete all the requested tasks, we excluded all their responses and reassigned their articles to a new participant a few days later. Indeed, out of an original sample of 140 subjects, 9 failed one or more attention checks, and 23 left the survey incomplete. All additional subjects recruited to substitute them completed the survey and passed all attention checks. The final sample included 146 participants and was collected over approximately 98 days. The sample is balanced by gender, with 48.6% self-identifying as female and 48.6% as male. The average age was 19.3 years (SD = 0.9), with the vast majority being undergraduate students and only one graduate student. Of the 146 participants, 126 (86.3%) were Spanish citizens. The remaining 20 participants were of various nationalities, with 90% of these foreign participants having lived in Spain for at least one year. The median completion time for all three news items was 17.43 minutes, with approximately 90% completing the task in 33.38 minutes or less.

It is worth noting that, compared to typical crowdsourcing platforms such as MTurk or Prolific—two widely used tools in academic research—our subject pool is arguably more educated and context-aware. In fact, we recruited students from ESADE—a top-ranked Spanish university frequently relied upon by economics and business-school researchers to hire research assistants—because the tasks in this study require familiarity with Spanish municipal politics and a solid understanding of fiscal terminology. While this sample may not fully represent professional annotators such as policy researchers, journalists, or domain-trained crowd workers, we believe it compares favorably to the untrained participants typically used in studies that rely on outsourced coders. Given that our goal in this study is not to define a universal benchmark for human performance, but to evaluate the extent to which LLMs and traditional outsourced coders can replicate the judgments of highly skilled annotators, our sample of outsourced human coders provides an appropriate—and meaningfully strong—group against which to compare LLMs.

Performance metrics

Having obtained annotations from high-skilled coders (our gold standard), LLMs, and outsourced human coders, our goal is to evaluate how closely the latter two groups replicate the judgments of the former. In this section, we describe the metrics used to assess performance across the different task types. As explained in Section "Coding strategies", the tasks assigned to LLMs and outsourced coders correspond to various NLP task families. T1 corresponds to a NER problem, for which we use the macro-averaged \(\text {F}_1\) score as the performance metric. This metric averages the \(\text {F}_1\) scores calculated separately for each article. An article’s \(\text {F}_1\) score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Precision measures how many of the municipalities identified by the coder (LLM or human) are correct, while recall measures how many of the correct municipalities (from the gold standard) the coder successfully identified. Before computing these metrics, we correct any misspellings in the coders’ responses. All scores range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance.

During data collection, we requested two answers for every news article, resulting in 420 responses. This approach was applied consistently for both the outsourced human coders and each LLM tested. Considering this, we calculated the macro-averaged \(\text {F}_1\) score over these 420 responses. The obtained value should thus be interpreted as the estimated performance for a randomly selected news article and tagger. A similar approach is followed for calculating the performance metrics for the remaining tasks.

T2 corresponds to an entity counting task, framed as a regression problem and evaluated using the mean absolute error (MAE)—which captures the average absolute difference between a coder’s response and the gold standard value. Lower MAE scores indicate more accurate performance. T3 is a binary classification task with “yes” or “no” answers, though coders could also respond with “unsure” (coded as 99 for LLMs). We measure accuracy as the proportion of correct answers out of 420 responses, counting all “unsure” responses as incorrect (in no instance was “unsure” assigned in the gold standard labels).

Tasks T4 and T5 correspond to multi-label classification problems, where multiple correct responses are often possible. However, since LLMs and outsourced coders were indicated to provide a single label per article, we adopt a lenient evaluation metric: a prediction is considered correct if it matches any of the gold standard labels. We measure accuracy as the proportion of responses identifying any valid label, treating “the answer does not fit into any of the previous strategies” (code 98 for LLMs) as possibly correct and “unsure” (code 99 for LLMs) as incorrect. Note that “unsure” was never assigned in the expert annotations, although in some cases “the answer does not fit into any of the previous strategies” was the correct response. We acknowledge that this simplified metric likely inflates performance relative to a stricter multi-label standard, which would penalize missing or extraneous responses. However, following the objective in19, we aim to assess whether LLMs can reliably capture the core dimension of political attribution (ruling party vs. opposition), which can be conveyed by a single correct label. In this way, rather than replicating the full complexity and ambiguity of multi-label annotation, we prioritize a simplified and interpretable evaluation framework that emphasizes whether models grasp the central thrust of the criticism.

Results

In this section, we present our main results. Section "Overall performance" evaluates how well different coding strategies replicate the labels produced by high-skilled coders. Section "Factors influencing coders’ performance" explores how specific characteristics of the articles affect this performance. Section "Further analysis of the outsourced human coders’ performance" further assesses the quality and reliability of the annotations generated by outsourced human coders. Section "Prompt sensitivity" reports results obtained with an alternative prompting strategy, shedding light on the sensitivity of our findings to prompt design. Finally, Section "Internal consistency" examines the internal consistency of responses across coding strategies

Overall performance

Figure 1 summarizes the performance of outsourced human coders and LLMs across all five tasks (see Appendix Table D1 for detailed values). Higher values indicate better performance in all panels except for T2, where lower MAE values denote better accuracy. The final panel (“All correct”) reports the proportion of news articles for which a coder successfully completed all five tasks.

Overall performance, across tasks and coding strategies. This figure displays the overall performance across all tasks and coding strategies. For T1, the figure shows the Macro \(\text {F}_1\) score; for T2, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE); and for T3, T4, and T5, it shows the accuracy. For T2, a lower number denotes better performance (i.e., smaller errors in identifying the correct number of municipalities), while for the remaining tasks, higher numbers indicate better performance (i.e., closer alignment with the expert benchmark). The “All correct” panel indicates the proportion of news articles for which all tasks were completed entirely correctly, broken down by coding strategy.

Visual inspection of Fig. 1 reveals several notable patterns. First, all LLMs outperform outsourced coders across all tasks. Second, Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieves the highest scores across tasks, though often only marginally surpassing GPT-4-turbo. Third, while GPT-3.5-turbo outperforms outsourced humans, it lags behind other LLM models. This last result suggests that as LLMs continue to grow more powerful, the performance gap between them and outsourced human coders will only expand. These patterns are all confirmed in the regression analysis we present in Appendix C.1.

To have a better sense of how good is the performance of LLMs against the high-skill annotators that created the gold standard, we also computed the proportion of exact matches between the LLMs’ responses and the final gold standard labels. Note that this measure is directly analogous to the inter-coder agreement reported in Section "High-skill coders (gold standard labels)", with the key difference that one “coder” in the comparison is a model and the other is the expert-derived gold standard. Focusing on tasks where coding guidelines were identical across LLMs, outsourced coders, and high-skill annotators (T1–T3), and applying the 70% benchmark commonly cited in the inter-coder agreement literature56, we find that outsourced human coders fall short of this threshold, whereas the most advanced models from OpenAI (GPT-4) and Anthropic (Claude 3.5 Sonnet) meet or exceed it (see Appendix Table D2). Although, as noted earlier, agreement among the high-skilled annotators who produced the gold standard was somewhat higher (see Section "High-skill coders (gold standard labels)"), these results indicate that advanced LLMs not only outperform our pool of well-educated, context-aware outsourced coders across tasks, but also reach alignment levels that approach those of the expert annotators themselves.

Factors influencing coders’ performance

Task difficulty

Figure 2 replicates Fig. 1, presenting outcomes by task difficulty for each article (see Table D3 for detailed results), where a task in a given article is classified as difficult if at least two authors initially disagreed on the correct answer during the creation of the gold standard. In the “All correct” panel, an article is categorized as difficult if any of its tasks are classified as difficult.

Performance by article difficulty, across tasks and coding strategies. This figure displays the overall performance across all tasks and coding strategies classified by task difficulty. For T1, the figure shows the Macro \(\text {F}_1\) score; for T2, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE); and for T3, T4, and T5, it shows the accuracy. For T2, a lower number denotes better performance (i.e., smaller counting errors), while for the remaining tasks, higher numbers indicate better performance (i.e., greater agreement with gold-standard labels). The “All correct” panel indicates the proportion of news articles for which all tasks were completed entirely correctly, broken down by coding strategy.

Figure 2 shows that performance declines with task difficulty across all tasks, with GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4-turbo in T3 being the only exceptions to this pattern. Moreover, visual inspection of Fig. 2 shows that more advanced models, such as Claude 3.5 Sonnet and GPT-4-turbo, generally perform better on the difficult tasks than outsourced human coders do on the easier ones. Examining GPT-3.5-turbo’s performance in T4 and the “All correct” metric—the two cases where it did not significantly outperform human coders in the full sample (see Fig. 1 and Table C2)—reveals that it still achieves higher accuracy than outsourced human coders on difficult articles (see Appendix Table C2). This finding suggests that even the lowest-performing LLM in our analysis surpasses human coders in accuracy when faced with more challenging tasks.

Text length

Text length has been identified as an important factor affecting LLMs performance. For instance, LLMs are known to exhibit the “lost-in-the-middle” effect, where information appearing in the middle of the input tends to receive less attention than content at the beginning or end61. Similarly, human readers generally find longer texts more challenging to process than shorter ones. For this reason, in Fig. 3 we replicate Fig. 1, but with outcomes separated based on the length of the news articles (see Table D3 for detailed results). We define an article as “long” if its word count (as provided by Factiva) is larger than the \(90^{th}\) percentile calculated over our sample of 210 news articles analyzed, and “regular” otherwise.

Performance by article length, across tasks and coding strategies. This figure displays the overall performance across all tasks and coding strategies classified by article length. For T1, the figure shows the Macro \(\text {F}_1\) score; for T2, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE); and for T3, T4, and T5, it shows the accuracy. For T2, a lower number denotes better performance (i.e., fewer numeric discrepancies), while for the remaining tasks, higher numbers indicate better performance (i.e., greater match with expert annotations). The “All correct” panel indicates the proportion of news articles for which all tasks were completed entirely correctly, broken down by coding strategy.

Both Fig. 3 and the long-article indicator in Appendix Table C1 suggest that longer articles present greater challenges for coders, whether human or LLMs. In all tasks except T1, performance declines noticeably for long articles compared to shorter ones. Notably, visual inspection of the figure reveals that LLMs often outperform human coders on long articles—even exceeding human performance on shorter ones.

Further analysis of the outsourced human coders’ performance

The results presented above show that LLMs consistently outperform outsourced human coders on the tasks examined in this study. However, one might question whether this advantage stems not from LLMs excelling, but rather from shortcomings in how outsourced human annotators completed their assignments. In this section, we present evidence suggesting that 1) outsourced human coders performed competently, and 2) the main results of the study hold even when restricting the analysis to a subset of high-performing human coders.

Outsourced coders’ competence and task performance

Figure 4 provides evidence indicating that outsourced human responses were indeed competent by presenting two complementary analyses. First, for tasks T1 through T5, we assess the extent to which the overall performance of human-provided answers differs from what would be expected by pure chance. Specifically, for each task’s performance metric, we conducted a permutation test and calculated the upper confidence interval at the \(97.5^{\text {th}}\) percentile. A result is considered significant at the 5% level if the observed value exceeds this upper threshold (plotted as a black vertical line), except for T2, where it is considered significant if it falls below the threshold (see Appendix Table D5 for detailed results). In this test, the predicted values are permuted 2,000 times and the metric is computed for each permutation, generating a null distribution. Then, the observed metric is deemed significant if it surpasses the \(97.5^{\text {th}}\) percentile of this distribution. Second, to examine whether participants became fatigued or disengaged as the task progressed, we analyze performance trends based on the order in which participants reviewed the news articles. Recall that each participant completed tasks for three articles in sequence (see Appendix Table D6 for detailed results). If fatigue were a factor, we would expect lower accuracy on the final article compared to the first.

Human coders’ performance, statistical significance, and task progression. This figure shows the performance distribution by task order for the outsourced human coders. For T1, the figure shows the Macro \(\text {F}_1\) score; for T2, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE); and for T3, T4, and T5, it shows the accuracy. For T2, a lower number denotes better performance (i.e., more accurate counts), while for the remaining tasks, higher numbers indicate better performance (i.e., closer alignment with expert judgments). The “All correct” panel indicates the proportion of news articles for which all tasks were completed entirely correctly. For T1, T3, T4, and T5, observed values above the black line indicate performance significantly better than random chance in the permutation tests (5% level), while for T2, observed values below the line indicate significantly better performance.

Figure 4 shows that, for all tasks, human coders performed significantly above random chance. Their accuracy peaked when coding the second news article, surpassing both their first and last article performance, suggesting a pattern of initial learning followed by fatigue (see Appendix Table C3). This contrasts with LLMs, which maintain consistent performance across all articles, as they are not susceptible to fatigue and do not need to learn.

Analysis of high-performing outsourced human coders

To further ensure that our findings reflect the superior performance of LLMs rather than potential limitations of outsourced human coders, we conducted an additional analysis focusing on high-performing coders. For each human coder, we calculated an aggregate performance score based on the proportion of tasks they completed correctly (recall that most outsourced coders were assigned three news articles, each with five tasks, totaling 15 tasks). Using these scores, Fig. 5 replicates the analysis presented in Fig. 1, restricting it to coders whose performance was above the sample median (i.e., the top 50%). Notably, strong performance may reflect both individual ability and the difficulty of the articles assigned. To ensure a fair comparison, we recalculated LLM performance using only the same articles evaluated by these high-performing coders.

Performance comparison between LLMs and high-performing human coders. This figure compares the performance of high-performing human coders (above median aggregate performance) against LLMs across all tasks and coding strategies. For T1, the figure shows the Macro \(\text {F}_1\) score; for T2, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE); and for T3, T4, and T5, it shows the accuracy. For T2, a lower number denotes better performance (i.e., smaller numeric deviation from the correct count), while for the remaining tasks, higher numbers indicate better performance (i.e., higher agreement with expert coders). The “All correct” panel indicates the proportion of news articles for which all tasks were completed entirely correctly, broken down by coding strategy.

The results, shown in Fig. 5, reveal that while high-performing human coders achieved accuracy comparable to or occasionally exceeding GPT-3.5-turbo, their performance remained consistently below that of more advanced LLMs. This finding is particularly noteworthy given that our full sample of outsourced coders likely possesses higher capabilities than typical workers from popular crowdsourcing platforms. Thus, the analysis demonstrates that current LLMs perform at least as well as (in the case of GPT-3.5-turbo) or better than (for all other LLMs) the top performers in this already capable population.

Prompt sensitivity

A common concern when working with LLMs is the lack of a standardized approach for constructing effective prompts. In practice, prompt writing remains a creative and largely manual process, often relying on trial and error to identify the formulation that yields the best results for a given task. Following the debate in the literature on whether LLMs are best deployed as zero-shot or few-shot annotators18,62, we repeated the analyses in Section "Overall performance" and Section "Factors influencing coders’ performance" using new draws obtained in August 2025 for GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4-turbo under two conditions: our baseline zero-shot setting and an instruction-augmented setting. The latter enriches the baseline prompt with additional guidance, such as clarifying notes to reduce ambiguity (e.g., distinguishing municipalities from provinces), two illustrative examples of what qualifies as a “criticism,” and an explicit warning that negative descriptions do not always imply criticism (see Appendix B.4 for the alternative prompt). Results reported in Appendix Tables D7, D8, and D9 indicate that this enriched prompt design produces no systematic improvement in performance, even for long or difficult articles. While these results are not definitive, they provide preliminary evidence that, at least in our setting, a zero-shot approach could be sufficient.

Internal consistency

A desirable property of any coding strategy is its ability to yield consistent results across repeated trials. To assess this, Table 2 reports the internal consistency of each method based on paired responses. Recall that we obtained two responses per article from both human coders and each LLM. In this analysis, for each article and task, we treat the second response as the true label and compute the performance metrics described in Section "Performance metrics", using the first response as the prediction. Note that a coding strategy with high internal consistency should yield performance metrics close to their theoretical optimum—that is, higher values for accuracy-based measures and lower values for MAE.

Table 2 shows that all LLMs demonstrate high internal consistency, consistent with their minimum temperature setting. While this consistency is not perfect, it substantially exceeds that of human coders. In Appendix C.2, we further examine GPT-3.5-turbo’s temporal consistency by comparing responses generated at different points in time, recognizing that model behavior can shift with updates. The results presented in Appendix Table C4 reveal stronger consistency within responses generated in April 2024 (the main data used in this study) than between these responses and those from October 2023 (the runs used in19), or between the April 2024 responses and the August 2025 runs (analyzed in Section "Prompt sensitivity"). This suggests that even with minimized temperature settings, updates to the underlying model can introduce variation. Moreover, as shown in Appendix Table C5, these updates did not systematically improve performance, with notable declines in T3, T4, and T5, in line with the findings of63. Thus, while newer and more advanced models clearly outperform their predecessors (e.g., GPT-4-turbo compared to GPT-3.5-turbo), we find no evidence that within-model updates lead to steady improvements over time.

Discussion and conclusions

Our analysis shows that modern generative LLMs significantly outperform outsourced human coders in replicating annotations from high-skilled coders across a diverse series of tasks. Even though outsourced coders perform substantially better than random chance, LLMs consistently achieve higher accuracy and greater internal consistency in aligning with expert annotations. Importantly, these advantages persist even for challenging and lengthier texts, demonstrating the robustness and versatility of LLMs in complex textual analysis. Furthermore, our results highlight clear performance gains in newer generations of LLMs, which surpass even the best-performing outsourced annotators and are comparable to the high-skill annotators who elaborated the gold standard.

Practical implications

The findings from this study have meaningful practical implications for research practices in the social and behavioral sciences. As text data becomes increasingly central to understanding complex social and economic dynamics64,65,66,67, the ability to process such data effectively and efficiently is essential. Within this context, our findings demonstrate that advanced generative LLMs can serve as powerful tools for conducting sophisticated text analyses—regardless of the user’s technical background. Their accessibility through simple API calls, combined with modest operational costs, makes these models particularly well suited to replicating high-quality annotations at scale. With continued improvements in model capabilities, these technologies are poised to transform standard analytical workflows in the social and behavioral sciences, opening new opportunities for rigorous, scalable, and inclusive research designs.

Limitations and future work

While this study contributes important new evidence on how LLMs compare to outsourced human annotators across a range of NLP tasks, it also presents limitations and leaves open important questions. We outline these below, along with directions for future research.

Benchmarking against supervised baselines. This study focuses on evaluating how well zero-shot LLMs replicate the annotations of high-skilled coders relative to outsourced human annotators. As such, it does not benchmark against state-of-the-art SML models—such as fine-tuned BERT variants or multilingual transformers like XLM-R—which typically require labeled data and additional engineering. Prior work shows that the relative performance of zero-shot LLMs versus fine-tuned SML models is highly dependent on task, language, and domain. In some text classification settings, smaller fine-tuned models outperform zero-shot prompting68,69,70, while in other contexts, frontier LLMs rival or exceed supervised baselines50,71. The annotated corpus we release—covering five linguistically and contextually rich NLP tasks in Spanish—provides a strong foundation for future research to explore these comparisons more systematically72.

Task complexity and generalization. While our study evaluates a broader range of tasks than most existing human-LLM comparisons—spanning structured information extraction (T1-T2) and complex political inference (T3-T5)—it still covers only a subset of the broader space of natural language understanding. In particular, we do not examine higher-order capabilities such as multi-sentence summarization, natural language inference (e.g., contradiction or entailment), or causal reasoning—tasks increasingly used to probe deeper comprehension and abstraction in LLMs73,74. Also related to task complexity, for the multi-label classification tasks (T4-T5), we simplified the setup by requiring a single label from both models and outsourced coders, and we adopted a lenient evaluation rule that counted any overlap with the gold standard as correct. While grounded in both conceptual and practical motivations, we recongize this simplification likely inflates reported performance—for both LLMs and outsourced human coders—and limits generalizability. Future work could revisit T4-T5 in their full multi-label form and extend the benchmark to include higher-order tasks.

Reproducibility. A key practical limitation of using LLMs in research pipelines is the challenge of reproducibility. Even under “deterministic” decoding settings, identical prompts can yield different outputs across runs or following provider-side model updates57,58. In our study, LLMs exhibited high—though not perfect—internal consistency, substantially outperforming human coders (Table 2). Still, comparisons of GPT-3.5-turbo across time revealed meaningful version-based variation and modest performance declines in T3-T5. To support replicability and cumulative science, the research community should work toward establishing shared best practices for tracking model versions and decoding parameters, reporting performance variability alongside aggregate metrics, and adopting periodic re-evaluation protocols when using evolving commercial APIs.

Alternative outsourced annotation strategies and hybrid workflows. Our study compares fully human annotation—via outsourced coders—with fully automated annotation using LLMs. The human coders were recruited from Spanish university students, who possess strong linguistic proficiency and contextual awareness—a considerably higher bar than that of typical unskilled crowdsourced workers. As such, the performance gains we report for LLMs may be conservative, as the gap could widen when compared to less skilled annotators7. That said, a broad spectrum of alternative annotation strategies exists. At the high end of the expertise scale, policy researchers or native journalists offer deep subject-matter knowledge, but their relative scarcity makes them difficult to recruit at scale—posing challenges for large-scale research applications75. More recently, vendor-managed annotation platforms (e.g., Appen, Surge) have emerged as scalable options, offering project management and multi-layer quality control for high-volume commercial workflows. However, these services involve substantial fixed overhead and may be ill-suited for smaller academic studies76. Lastly, an increasingly popular alternative is hybrid annotation, where LLMs generate initial labels and humans verify or revise them. Recent research suggests that such workflows can improve efficiency and accuracy—particularly when verification is selective or interface-supported77,78. However, the evidence on when human-AI teaming yields net benefits remains mixed79. Future work could use our corpus to systematically benchmark LLMs across this full continuum—from general crowdworkers and university students, to domain experts and platform-managed annotators, as well as hybrid approaches.

Language generalizability. By evaluating Spanish-language news, this study contributes to the still limited but growing body of NLP research conducted beyond English80. While Spanish is not a low-resource language per se, it remains underrepresented in many existing benchmarks (see Table 1)—which is particularly consequential given that current LLMs are predominantly trained on English-language data and typically achieve superior performance on English tasks81,82. Future work should extend this framework to truly low-resource linguistic contexts, where disparities in model performance and data availability are even more pronounced83. Recent multilingual benchmarks and community-driven efforts offer promising tools for assessing how typological diversity, linguistic coverage, and resource availability influence model behavior across languages84,85.

Cost-efficiency and prompt sensitivity. LLMs offer substantial reductions in both time and financial costs compared to traditional supervised approaches, primarily by removing the need for task-specific labeled datasets and model training. However, they also introduce practical challenges, in particular prompt engineering. As discussed in Section "Prompt sensitivity", model performance can vary with small changes in formatting or phrasing, underscoring the importance of careful prompt design and iterative refinement86,87. These tuning efforts, though often invisible in the final output, may contribute meaningfully to the overall cost of implementing LLM-based pipelines. Future work should aim to make these hidden costs more transparent, evaluate how prompt strategies transfer across tasks, and investigate mitigation techniques—such as prompt standardization—to promote a more stable, scalable, and accessible use of LLMs.

Reliability, bias, and ethical considerations. Despite their many advantages, LLMs carry important reliability risks—most notably hallucinations (confident but incorrect outputs)—which are particularly pronounced in fine-grained, context-sensitive tasks like T4 and T588,89. These risks are further exacerbated by the opaque nature of model reasoning, which limits interpretability and raises accountability concerns in sensitive domains such as sociopolitical classification90. In such settings, replacing human judgment with model outputs may introduce unexamined political priors or normative biases. Recent research has shown that even zero-shot prompting can reveal latent ideological leanings or value misalignments that often go unnoticed without targeted auditing91,92,93. In Appendix C.3, we conduct a preliminary analysis to assess whether, in our context, LLMs—while generally precise—may have a pattern in their mistakes, finding no evidence of political bias. Future work could also use benchmarks like the one introduced by94, which provide a human-centric template for evaluating models along dimensions such as fairness, ethics, and robustness, to do analogous efforts in other text-based domains.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the remarkable capabilities of generative LLMs in handling complex text analysis tasks, showing a clear advantage over traditional outsourced human annotation methods in replicating high-skilled coders’ responses. These findings support the adoption of LLMs as a practical, efficient, and accessible tool for researchers, with the potential to enhance both analytical rigor and productivity in the social sciences and beyond. As NLP technology continues to advance, the role of LLMs in text-based research is likely to grow, opening up new opportunities for methodological innovation and large-scale, high-quality analysis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barberá, P., Boydstun, A. E., Linn, S., McMahon, R. & Nagler, J. Automated text classification of news articles: A practical guide. Political Anal. 29, 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2020.8 (2021).

Rathje, S. et al. Gpt is an effective tool for multilingual psychological text analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2308950121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308950121 (2024).

Gentzkow, M., Kelly, B. & Taddy, M. Text as data. J. Econ. Lit. 57, 535–74. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181020 (2019).

Song, H. et al. In validations we trust? the impact of imperfect human annotations as a gold standard on the quality of validation of automated content analysis. Political Commun. 37, 550–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723752 (2020).

Grimmer, J. & Stewart, B. M. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Anal. 21, 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028 (2013).

Pustejovsky, J. & Stubbs, A. Natural Language Annotation for Machine Learning (O’Reilly Media, Incorporated, 2012).

Snow, R., O’Connor, B., Jurafsky, D. & Ng, A. Cheap and fast – but is it good? evaluating non-expert annotations for natural language tasks. In Lapata, M. & Ng, H. T. (eds.) Proceedings of the 2008 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 254–263 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Honolulu, Hawaii, 2008).

Callison-Burch, C. Fast, cheap, and creative: Evaluating translation quality using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. In Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds. Koehn, P. & Mihalcea, R.) 286–295 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Singapore, 2009).

Sabou, M., Bontcheva, K., Derczynski, L. & Scharl, A. Corpus annotation through crowdsourcing: Towards best practice guidelines. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14) (eds. Calzolari, N. et al.) 859–866 (European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Reykjavik, Iceland, 2014).

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. M. & Sinkinson, M. Competition and ideological diversity: Historical evidence from us newspapers. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 3073–3114 (2014).

Gentzkow, M., Petek, N., Shapiro, J. M. & Sinkinson, M. Do newspapers serve the state? incumbent party influence on the us press, 1869–1928. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 13, 29–61 (2015).

Barbaglia, L., Consoli, S., Manzan, S., Tiozzo Pezzoli, L. & Tosetti, E. Sentiment analysis of economic text: A lexicon-based approach. Econ. Inq. 63, 125–143 (2025).

Ang, D. The birth of a nation: Media and racial hate. Am. Econ. Rev. 113, 1424–1460 (2023).

Couttenier, M., Hatte, S., Thoenig, M. & Vlachos, S. Anti-muslim voting and media coverage of immigrant crimes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 106, 576–585 (2024).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Burstein, J., Doran, C. & Solorio, T. (eds.) Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1423 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019).

Gilardi, F., Alizadeh, M. & Kubli, M. Chatgpt outperforms crowd workers for text-annotation tasks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2305016120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2305016120 (2023).

Naveed, H. et al. A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1145/3744746 (2025). Just Accepted.

Kojima, T., Gu, S. S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y. & Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds. Koyejo, S. et al.) vol. 35, 22199–22213 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022).

Bermejo, V. J., Gago, A., Abad, J. & Carozzi, F. Government Turnover and External Financial Assistance https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4520859 (2023).

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E. & Hancock, J. T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8788–8790. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111 (2014).

Angelico, C., Marcucci, J., Miccoli, M. & Quarta, F. Can we measure inflation expectations using twitter?. J. Econom. 228, 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.12.008 (2022).

González-Bailón, S. et al. Asymmetric ideological segregation in exposure to political news on facebook. Science 381, 392–398 (2023).

Guess, A. M. et al. Reshares on social media amplify political news but do not detectably affect beliefs or opinions. Science 381, 404–408 (2023).

Romer, C. D. & Romer, D. H. Does monetary policy matter? a new test in the spirit of friedman and schwartz. NBER Macroecon. Annu. 4, 121–170 (1989).

Barro, R. J. & Redlick, C. J. Macroeconomic effects from government purchases and taxes. Q. J. Econ. 126, 51–102 (2011).

Mertens, K. & Ravn, M. O. Empirical evidence on the aggregate effects of anticipated and unanticipated us tax policy shocks. Am. Econ. J.: Econ. Policy 4, 145–181 (2012).

Mertens, K. & Ravn, M. O. The dynamic effects of personal and corporate income tax changes in the united states. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 1212–1247 (2013).

Quinn, K. M., Monroe, B. L., Colaresi, M., Crespin, M. H. & Radev, D. R. How to analyze political attention with minimal assumptions and costs. Am. J. Political Sci. 54, 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00427.x (2010).

Grimmer, J. & King, G. General purpose computer-assisted clustering and conceptualization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 2643–2650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018067108 (2011).

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. M. & Taddy, M. Measuring group differences in high-dimensional choices: method and application to congressional speech. Econometrica 87, 1307–1340 (2019).

Ferrara, E. L., Chong, A. & Duryea, S. Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from brazil. Am. Econ. J.: Appl. Econ. 4, 1–31 (2012).

Gálvez, R. H., Tiffenberg, V. & Altszyler, E. Half a century of stereotyping associations between gender and intellectual ability in films. Sex Roles 81, 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01019-x (2019).

Bertsch, A. et al. Evaluating gender bias transfer from film data. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing (GeBNLP) (eds. Hardmeier, C., Basta, C., Costa-jussà, M. R., Stanovsky, G. & Gonen, H.) 235–243, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.gebnlp-1.24 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Seattle, Washington, 2022).

Vial, A. C. et al. Syntactic and semantic gender biases in the language on children’s television: Evidence from a corpus of 98 shows from 1960 to 2018Psychol. Sci. 36, 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976251349815 (2025). PMID: 40658873 (1960).

Gentzkow, M. & Shapiro, J. M. What drives media slant? evidence from u.s. daily newspapers. Econometrica 78, 35–71. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195 (2010).

Capozza, F., Haaland, I., Roth, C. & Wohlfart, J. Recent advances in studies of news consumption. Working Paper 10021, CESifo (2022). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4257220.

Ramey, V. A. Identifying government spending shocks: It’s all in the timing. Q. J. Econ. 126, 1–50 (2011).

Gunter, S., Riera-Crichton, D., Vegh, C. A. & Vuletin, G. Non-linear effects of tax changes on output: The role of the initial level of taxation. J. Int. Econ. 131, 103450 (2021).

Jalil, A. J. A new history of banking panics in the united states, 1825–1929: construction and implications. Am. Econ. J.: Macroecon. 7, 295–330 (2015).

García-Uribe, S., Mueller, H. & Sanz, C. Economic uncertainty and divisive politics: evidence from the dos españas. J. Econ. Hist. 84, 40–73 (2024).

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N. & Terry, S. J. Using disasters to estimate the impact of uncertainty. Rev. Econ. Stud. 91, 720–747 (2024).

Barbaglia, L., Consoli, S. & Manzan, S. Forecasting with economic news. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 41, 708–719 (2023).

Durante, R. & Zhuravskaya, E. Attack when the world is not watching? us news and the israeli-palestinian conflict. J. Political Econ. 126, 1085–1133 (2018).

Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M. & Sonin, K. Social media and corruption. Am. Econ. J.: Appl. Econ. 10, 150–174 (2018).

Dougal, C., Engelberg, J., Garcia, D. & Parsons, C. A. Journalists and the stock market. Rev. Financ. Stud. 25, 639–679 (2012).

Lopez-Lira, A. & Tang, Y. Can chatgpt forecast stock price movements? return predictability and large language models (2024). arxiv:2304.07619.

Luo, D. et al. Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination. Sci. Rep. 15, 14119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98949-2 (2025).

Taloni, A. et al. Comparative performance of humans versus GPT-4.0 and GPT-3.5 in the self-assessment program of American Academy of Ophthalmology. Sci. Rep. 13, 18562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45837-2 (2023).

Yeadon, W., Peach, A. & Testrow, C. A comparison of human GPT-3.5, and GPT-4 performance in a university-level coding course. Sci. Rep. 14, 23285. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73634-y (2024).

Törnberg, P. Large language models outperform expert coders and supervised classifiers at annotating political social media messages. Social Science Computer Review 0 (0), https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393241286471 (2024).

Ziems, C. et al. Can large language models transform computational social science?. Comput. Linguist. 50, 237–291. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00502 (2024).

Bojić, L. et al. Comparing large language models and human annotators in latent content analysis of sentiment, political leaning, emotional intensity and sarcasm. Sci. Rep. 15, 11477. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96508-3 (2025).

Kaikaus, J., Li, H. & Brunner, R. J. Humans vs. chatgpt: Evaluating annotation methods for financial corpora. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), 2831–2838, https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData59044.2023.10386425 (2023).

Huang, F., Kwak, H. & An, J. Is chatgpt better than human annotators? potential and limitations of chatgpt in explaining implicit hate speech. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, WWW ’23 Companion, 294–297, https://doi.org/10.1145/3543873.3587368 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2023).

Leas, E. C. et al. Using large language models to support content analysis: A case study of chatgpt for adverse event detection. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e52499. https://doi.org/10.2196/52499 (2024).

Graham, M., Milanowski, A. T. & Miller, J. Measuring and Promoting Inter-Rater Agreement of Teacher and Principal Performance Ratings (ERIC Clearinghouse, [S.l.], 2012). Electronic resource.

Song, Y., Wang, G., Li, S. & Lin, B. Y. The good, the bad, and the greedy: Evaluation of LLMs should not ignore non-determinism. In Chiruzzo, L., Ritter, A. & Wang, L. (eds.) Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 4195–4206, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.naacl-long.211 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025).

Atil, B. et al. Non-determinism of “deterministic” llm settings (2025). arxiv:2408.04667.

Benoit, K., Conway, D., Lauderdale, B. E., Laver, M. & Mikhaylov, S. Crowd-sourced text analysis: Reproducible and agile production of political data. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 110, 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000058 (2016).

Hauser, D., Paolacci, G. & Chandler, J. Common concerns with mturk as a participant pool: Evidence and solutions. In Handbook of research methods in consumer psychology, 319–337 (Routledge, 2019).

An, S., Ma, Z., Lin, Z., Zheng, N. & Lou, J.-G. Make your llm fully utilize the context arxiv:2404.16811 (2024).

Brown, T. B. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arxiv:2005.14165 (2020).

Chen, L., Zaharia, M. & Zou, J. How is chatgpt’s behavior changing over time? arxiv:2307.09009 (2023).

Tseng, Y.-H., Lin, C.-J. & Lin, Y.-I. Text mining techniques for patent analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 43, 1216–1247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2006.11.011 (2007). Patent Processing.

Galiani, S., Gálvez, R. H. & Nachman, I. Specialization trends in economics research: A large-scale study using natural language processing and citation analysis. Econ. Inq. 63, 289–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.13261 (2025).

Haaland, I. K., Roth, C., Stantcheva, S. & Wohlfart, J. Measuring what is top of mind. Tech. Rep. (2024).

Keita, S., Renault, T. & Valette, J. The usual suspects: Offender origin, media reporting and natives’ attitudes towards immigration. Econ. J. 134, 322–362 (2024).

Bucher, M. J. J. & Martini, M. Fine-tuned ’small’ llms (still) significantly outperform zero-shot generative ai models in text classification. arxiv:2406.08660 (2024).

Zhang, W., Deng, Y., Liu, B., Pan, S. & Bing, L. Sentiment analysis in the era of large language models: A reality check. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024 (eds. Duh, K., Gomez, H. & Bethard, S. eds.), 3881–3906, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.findings-naacl.246 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Mexico City, Mexico, 2024).

Wu, C. et al. Evaluating zero-shot multilingual aspect-based sentiment analysis with large language models. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-025-02711-z (2025).

Li, X. et al. Are ChatGPT and GPT-4 general-purpose solvers for financial text analytics? a study on several typical tasks. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track (eds. Wang, M. & Zitouni, I.) 408–422, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-industry.39 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Singapore, 2023).

Fatemi, S., Hu, Y. & Mousavi, M. A comparative analysis of instruction fine-tuning large language models for financial text classification. ACM Trans. Manage. Inf. Syst. 16, https://doi.org/10.1145/3706119 (2025).

Zhang, T. et al. Benchmarking large language models for news summarization. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 12, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00632 (2024).

Ma, J. Causal inference with large language model: A survey. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025 (eds. Chiruzzo, L., Ritter, A. & Wang, L.) 5886–5898, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.findings-naacl.327 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025).

Kittur, A. et al. The future of crowd work. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW ’13, 1301–1318, https://doi.org/10.1145/2441776.2441923 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2013).

Gray, M. & Suri, S. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019).

Kim, H., Mitra, K., Li Chen, R., Rahman, S. & Zhang, D. MEGAnno+: A human-LLM collaborative annotation system. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations (eds. Aletras, N. & De Clercq, O.) 168–176, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.eacl-demo.18 (Association for Computational Linguistics, St. Julians, Malta, 2024).

Wang, X., Kim, H., Rahman, S., Mitra, K. & Miao, Z. Human-llm collaborative annotation through effective verification of llm labels. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’24, https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3641960 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2024).

Vaccaro, M., Almaatouq, A. & Malone, T. When combinations of humans and ai are useful: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 2293–2303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02024-1 (2024).

Joshi, P., Santy, S., Budhiraja, A., Bali, K. & Choudhury, M. The state and fate of linguistic diversity and inclusion in the NLP world. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (eds. Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N. & Tetreault, J. eds.) 6282–6293, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.560 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 2020).

Huang, H. et al. Not all languages are created equal in LLMs: Improving multilingual capability by cross-lingual-thought prompting. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 (eds. Bouamor, H., Pino, J. & Bali, K.) 12365–12394, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.826 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Singapore, 2023).

Etxaniz, J., Azkune, G., Soroa, A., Lacalle, O. & Artetxe, M. Do multilingual language models think better in English? In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 2: Short Papers) (eds. Duh, K., Gomez, H. & Bethard, S.) 550–564, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.naacl-short.46 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Mexico City, Mexico, 2024).

Blasi, D., Anastasopoulos, A. & Neubig, G. Systematic inequalities in language technology performance across the world’s languages. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Muresan, S., Nakov, P. & Villavicencio, A.) 5486–5505, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.376 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 2022).

Adelani, D. I. et al. MasakhaNER 2.0: Africa-centric transfer learning for named entity recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds. Goldberg, Y., Kozareva, Z. & Zhang, Y.) 4488–4508, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.298 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022).

Adelani, D. I. et al. IrokoBench: A new benchmark for African languages in the age of large language models. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Chiruzzo, L., Ritter, A. & Wang, L.) 2732–2757, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.naacl-long.139 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025).

Sclar, M., Choi, Y., Tsvetkov, Y. & Suhr, A. Quantifying language models’ sensitivity to spurious features in prompt design or: How i learned to start worrying about prompt formatting. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Gan, C. & Mori, T. Sensitivity and robustness of large language models to prompt template in Japanese text classification tasks. In Proceedings of the 37th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (eds. Huang, C.-R. et al.) 1–11 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Hong Kong, China, 2023).

Huang, L. et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 43, https://doi.org/10.1145/3703155 (2025).