Abstract

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) pose a growing threat in healthcare settings. Timely detection through active surveillance is essential for infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship. This study investigated the prevalence and microbiological profile of MDRO colonization among hospitalized patients at AHEPA University Hospital in Thessaloniki, Greece. A prospective surveillance study was conducted from October 2024 to January 2025 across multiple hospital wards. Screening swabs from the rectum, groin, and nares were obtained upon admission or during hospitalization. Microbiological analysis targeted key MDROs, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Candida auris, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Among 1206 patients screened, 308 (25.5%) tested positive for at least one MDRO. Rectal swabs yielded the highest detection rates, predominantly identifying K. pneumoniae and VRE. Candida auris was most frequently isolated from groin swabs, while nasal swabs rarely detected MDROs. Internal medicine wards exhibited the highest colonization burden. Contact tracing and prolonged hospitalization were the most common indications for screening. This study highlights the high prevalence and diverse spectrum of MDRO colonization in a Greek tertiary hospital. Targeted screening- especially of rectal and groin sites-facilitates early detection and effective infection control. Continued surveillance is essential to mitigate MDRO transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global rise in multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) has become a major public health concern, particularly within healthcare facilities where vulnerable patient populations are at increased risk of colonization and subsequent infection. Colonization by MDROs such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida auris, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can lead to invasive infections, prolonged hospitalizations, and increased mortality1,2,3.

Surveillance of colonization is a key component of infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies. Active screening upon admission or during hospitalization enables timely identification of colonized individuals, initiation of contact precautions, and implementation of antimicrobial stewardship protocols4,5. The recent emergence of Candida auris has added urgency to routine screening due to its multidrug resistance, environmental persistence, and association with healthcare outbreaks6,7.

In Greece, the burden of MDROs remains disproportionately high, with recurrent hospital outbreaks and evidence of endemic transmission in tertiary care settings8,9. Several studies have documented the overall prevalence and clinical impact of MDROs nationwide; however, there is limited evidence on colonization dynamics in large academic hospitals in Northern Greece, particularly from systematic active surveillance programs. Understanding ward-specific and anatomical site–specific colonization patterns in this regional context is critical, as it can inform infection prevention strategies tailored to high-risk hospital environments.

This study aimed to determine the prevalence and distribution of MDRO colonization among hospitalized patients in a Greek tertiary hospital. Special emphasis was placed on the anatomical sites of colonization, ward-specific differences, and the detection of emerging pathogens such as Candida auris. Through systematic active screening and microbiological analysis, we sought to generate data that could inform IPC strategies and reinforce hospital-level surveillance practices.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a prospective surveillance study at AHEPA University Hospital, a tertiary academic hospital in Thessaloniki, Northern Greece, between October 2024 and January 2025. The study included patients admitted to internal medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, and surgical wards.

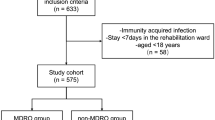

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for screening if they met at least one of the following criteria:

-

Hospitalization for more than 7 days (prolonged hospitalization),

-

Transfer from another healthcare facility or long-term care center,

-

Recent exposure to a confirmed MDRO-positive patient (contact tracing). Contact tracing was initiated following laboratory confirmation of MDRO colonization in a patient sharing the same ward or room within the previous 7 days.

-

Admission to a high-risk ward (e.g., intensive care unit, hematology),

-

History of prior colonization or infection with an MDRO, based on available microbiological records in the hospital database.

Sample collection

Sampling was performed by trained nursing staff using standard sterile technique. Not all patients were sampled at all sites. The anatomical sites and corresponding targets were:

-

Rectum—detection of Gram-negative bacilli and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE),

-

Groin (inguinal region)—detection of Candida auris and other MDROs,

-

Nares—detection of Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA.

Patients contributed more than one specimen when clinical risk factors indicated multi-site sampling. Specifically, additional sampling was performed in patients with: indwelling urinary or central venous catheters, recent or ongoing broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, chronic wounds or pressure ulcers, prior history of MDRO colonization or infection, or admission to a high-risk ward (e.g., intensive care, hematology).

Samples were transported immediately to the microbiology laboratory for processing. All specimens were collected using sterile eSwab™ collection systems (Copan Diagnostics, Italy), which include flocked swabs and liquid Amies transport medium. The same swab system was used across all anatomical sites to ensure consistency.

Microbiological analysis

All samples were cultured on appropriate selective media in accordance with standard microbiological protocols. Selective chromogenic media included: CHROMagar™ ESBL (CHROMagar, France) for extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacterales, CHROMagar™ VRE for vancomycin-resistant enterococci, CHROMagar™ MRSA for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and CHROMagar™ Candida Plus for Candida auris.

Identification of all isolates was performed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Biotyper). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the VITEK® 2 automated system (bioMérieux), and results were interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines (version 2024).

MDROs were defined as organisms demonstrating phenotypic resistance to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes.

Isolates growing on selective chromogenic media but not meeting the predefined MDRO definition (i.e., resistance to ≥ 3 antimicrobial classes) were excluded from the analysis. Such instances were rare (< 2% of total isolates) and primarily involved Enterobacterales producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) without additional resistance mechanisms. By restricting analyses to organisms fulfilling the ≥ 3 class criterion, we ensured consistent classification across all pathogens.

Data collection

For each screened patient, the following information was recorded:

-

Demographic data: age and sex,

-

Admission details: hospital ward and type of admission (e.g., emergency, scheduled),

-

Indication for screening: such as contact tracing or prolonged hospitalization,

-

Microbiological findings: identified species and resistance phenotype.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted as part of the hospital’s routine infection control surveillance program. Patient data were fully anonymized, and no interventions were performed. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Committee of AHEPA University General Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians prior to screening, in accordance with the approved hospital infection control protocol.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables—including colonization status, hospital ward, anatomical sampling site, and reason for screening—were summarized as counts and percentages. Continuous variables, such as age, were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) due to non-normal distribution. Comparisons between MDRO-colonized and non-colonized patients were conducted using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Associations between MDRO colonization and clinical variables—including hospital ward, anatomical sampling site (e.g., rectal vs. groin), and reason for screening—were assessed using contingency tables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Descriptive and comparative analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0), while R (version 4.3.1) was used for data visualization. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No correction for multiple comparisons was applied, as analyses were exploratory.

Results

Study population and sample distribution

A total of 1206 screening swabs were obtained from hospitalized patients at AHEPA University Hospital between October 2024 and January 2025. Samples were primarily collected from the rectum (n = 614), groin (n = 584), and nares (n = 1) as part of active surveillance for MDRO colonization. These swabs corresponded to approximately 1100 unique patients. Among them, 312 individuals (28.3%) contributed specimens from more than one anatomical site, most frequently rectum and groin.

The clinical risk factors guiding site-specific sampling are summarized in Table 1.

The main indications for screening were contact tracing (n = 406, 52.5%), prolonged hospitalization > 7 days (n = 276, 35.4%), transfer from another healthcare facility (n = 62, 8.0%), admission to a high-risk ward (n = 31, 4.0%), and prior MDRO history (n = 17, 2.2%). A detailed breakdown is provided in Table 2.

Due to incomplete documentation, indication data were available for 792 of 1100 patients (71.9%).

Baseline characteristics of screened patients stratified by MDRO colonization status are summarized in Table 3.

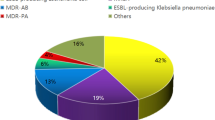

Overall colonization rates

Out of 1206 screening swabs collected, 308 (25.5%) tested positive for colonization with at least one MDRO, while 898 (74.5%) were negative (Supplementary Fig. 1).

At the patient level, 308 of approximately 1100 screened individuals (28.0%) were colonized with at least one MDRO. At the swab level, 308 of 1206 collected swabs (25.5%) were positive. Colonization rates therefore differed slightly depending on the denominator (patient vs. swab).

Among colonized individuals, 47 (15.3%) were co-colonized with two or more different MDRO species.

The most frequently identified organisms were Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 96), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 69), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE; n = 59), Acinetobacter spp. (n = 33), and Candida auris (n = 27) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Detailed positivity rates per MDRO and anatomical site are presented in Table 4.

Positivity rate calculated as number of positive swabs/number of swabs tested per site. For Acinetobacter spp., site-level breakdown was incomplete in the dataset.

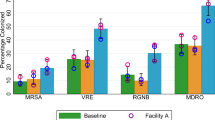

Temporal distribution of screening activity

As shown in Fig. 1, the number of screening samples and MDRO-positive results varied by month during the surveillance period (October 2024 to January 2025). In October, 250 samples were collected, of which 62 (24.8%) were positive. Screening activity peaked in November with 430 samples and 112 (26.0%) positive results, coinciding with internal infection control alerts. In December, 310 samples were obtained, with 88 (28.4%) testing positive. By January, sample volume decreased to 216, with 46 (21.3%) MDRO-positive cases.

These monthly fluctuations reflect variable screening intensity and underscore the sustained burden of MDRO colonization throughout the study period.

MDROs by sample type

Rectal swabs accounted for the majority of MDRO isolations. Specifically, they yielded 92 of 96 K. pneumoniae cases, all 59 VRE, and 46 of 69 P. aeruginosa isolates. Groin swabs were the primary source for C. auris, accounting for 24 of 27 cases. Acinetobacter spp. was detected in both rectal and groin swabs, while nasal swabs rarely yielded MDROs. Only one nasal swab was collected during the study period, and no MRSA isolates were recovered (Supplementary Fig. 3).

MDROs by ward type

Colonization rates varied across hospital departments (Supplementary Fig. 4). The Internal Medicine wards recorded the highest number of MDRO isolates (201 positive swabs, 30.8%), with predominant species including K. pneumoniae (n = 29), VRE (n = 37), and P. aeruginosa (n = 20).

In contrast, the Neurology and Neurosurgery wards demonstrated lower colonization frequencies, with 12/112 (10.7%) and 8/98 (8.2%) swabs positive, respectively. In the Surgical ward, MDRO detection was rare, with only three positive swabs (3.5%), including one MRSA and two C. auris isolates.

Approximately one quarter of swabs (n = 258, 21.4%) lacked complete ward assignment; of these, 84 (32.6%) were positive. These distributions are summarized in Table 5.

Summary

Approximately 25% of samples lacked complete ward assignment data and were therefore classified as “Other,” which limited the ability to fully assess ward-specific colonization trends. This accounts for the low or absent counts in certain categories within Supplementary Fig. 4.

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight a substantial MDRO colonization burden among internal medicine patients and reinforce the value of targeted anatomical screening—particularly rectal and groin swabs—for the detection of key MDROs such as K. pneumoniae, VRE, and C. auris. Focused sampling strategies proved effective for pathogen-specific surveillance and enabled ward-level epidemiological insights.

Discussion

The overall MDRO colonization rate observed in our study (25.5%) aligns with previous reports from Greek tertiary hospitals, where rates range between 20 and 30%, depending on patient population and screening practices8,9. This supports the ongoing endemicity of MDROs in the Greek healthcare setting.

Similar colonization trends have also been reported in other high-prevalence European countries, such as Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom—particularly for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Candida auris10,11,12. These international parallels highlight the shared burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) across Southern and Eastern Europe.

In this prospective observational study conducted at AHEPA University Hospital, we analyzed MDRO colonization patterns across multiple clinical wards. The most frequently isolated organisms were Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), consistent with prior studies identifying these pathogens as endemic in Greek hospitals13,14. Many of these strains harbor resistance mechanisms such as KPC, NDM, or VIM carbapenemases, which are especially prevalent in the Balkan region15.

A notable finding was the detection of Candida auris, primarily from groin swabs. As an emerging fungal pathogen with multidrug resistance and environmental persistence, C. auris poses a unique infection control challenge16,17. Its inclusion in surveillance programs is increasingly supported by recent outbreaks in Italy, Spain, and the UK10,11,12. Our results underscore the utility of targeted groin sampling, especially in contact tracing scenarios.

Rectal swabs yielded the highest number of positive cultures, particularly for Gram-negative organisms. This observation supports existing literature that identifies gastrointestinal colonization as a major reservoir for MDROs and a strong predictor of subsequent infection18,19. In our study, 95.8% of K. pneumoniae and all VRE cases were detected via rectal screening, reinforcing its diagnostic value20,21.

Ward-specific analysis revealed that internal medicine units had the highest MDRO colonization rates, followed by neurosurgery and neurology. This trend may reflect longer hospital stays, frequent antimicrobial exposure, greater patient complexity, and increased use of invasive devices in these wards22,23. Conversely, surgical wards exhibited relatively low MDRO prevalence, although sporadic cases of MRSA and C. auris were observed. These findings support the implementation of unit-specific risk assessments and tailored surveillance strategies.

Our results are particularly relevant in light of recent warnings from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the rising AMR burden in Europe, particularly in Southern and Eastern regions24,25. The high colonization rates observed here highlight the importance of integrating microbiological surveillance with antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs), environmental decontamination protocols, and continuous staff education. In addition, regular feedback of surveillance data to clinical teams is critical to maintaining adherence to infection prevention and control (IPC) practices26.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is its real-world applicability, as it reflects routine surveillance practices across multiple wards in a high-risk tertiary care hospital. The use of standard microbiological techniques enhances the external validity and reproducibility of the findings, supporting their relevance to similar healthcare settings.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the absence of molecular typing or resistance gene characterization limits our ability to investigate transmission dynamics or underlying resistance mechanisms. Second, approximately 25% of samples lacked specific ward assignment and were grouped under “Other,” which reduced the granularity of ward-level analyses and may explain low or missing counts in certain categories. Third, clinical outcomes of colonized patients—such as infection progression or mortality—were not assessed and represent a key area for future research. Lastly, nasal screening was notably underrepresented, highlighting the need for more balanced anatomical site sampling in future surveillance protocols.

Conclusion

This study underscores the substantial burden of MDRO colonization in hospitalized patients at a tertiary care hospital in Northern Greece. Active surveillance revealed high rates of colonization, particularly with multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and the emerging pathogen Candida auris. Rectal and groin sampling proved most effective, highlighting the importance of targeted, site-specific screening strategies.

Our findings support the continued integration of MDRO surveillance into routine infection prevention and control (IPC) practices, especially in internal medicine and other high-risk wards. Alignment with antimicrobial stewardship programs, staff training, and environmental decontamination is essential to minimize transmission.

Future research incorporating molecular diagnostics, clinical outcome tracking, and cost-effectiveness evaluations is needed to optimize surveillance protocols and guide data-driven interventions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional data protection policies and patient confidentiality regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18(3), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3 (2018).

Cassini, A. et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-4 (2019).

Magill, S. S. et al. Changes in prevalence of health care-associated infections in U.S. Hospitals. N. Engl. J. Med. 387(18), 1732–1744. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2201575 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facility guidance for control of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE): November 2015 Update – CRE Toolkit. (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2015).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) Infection Control (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2024).

Jeffery-Smith, A. et al. Candida auris: A review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31(1), e00029-e117. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00029-17 (2018).

Chowdhary, A., Sharma, C. & Meis, J. F. Candida auris: A rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog. 13(5), e1006290. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006290 (2017).

Galani, I. et al. Evolution of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece: A decade of genomic surveillance. Microorganisms 10(3), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10030555 (2022).

Tsakris, A. et al. Impact of infection control interventions on the spread of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria in a Greek tertiary care hospital. Am. J. Infect. Control 43(5), 486–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2014.12.017 (2015).

Ruiz-Gaitán, A. C. et al. An outbreak due to Candida auris with prolonged colonization and candidemia in a tertiary care European hospital. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24(7), 1160–1163 (2018).

Osei Sekyere, J. Current state of resistance to antibiotics of last-resort in South Africa: A review from a public health perspective. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00292 (2018).

17European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Candida auris outbreak in healthcare in northern Italy, 2019–2021 (ECDC, 2022).

Maraki, S., Mavromanolaki, V. E., Kasimati, A., Iliaki-Giannakoudaki, E. & Stafylaki, D. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance trends among lower respiratory tract pathogens in Crete, Greece, 2017–2022. Infect. Chemother. 56(4), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2024.0060 (2024).

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 399(10325), 629–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 (2022) (Epub 2022 Jan 19. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 1;400(10358):1102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02653-2).

Giske, C. G. et al. Clinical and microbiological data on multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in Europe: A multinational study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23(6), 401–410 (2017).

Chowdhary, A., Sharma, C. & Meis, J. F. Candida auris: A rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog. 13(5), e1006290 (2017).

Jeffery-Smith, A. et al. Candida auris: A review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31(1), e00029-e117. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00029-17 (2018).

Heath, M. R. et al. Gut colonization with multidrug resistant organisms in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 28, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-04999-9 (2024).

Li, Jg. et al. Colonization of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria increases risk of surgical site infection after hemorrhoidectomy: A cross-sectional study of two centers in southern China. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 38, 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-023-04535-1 (2023).

Dimartino, V. et al. Screening of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strains with multi-drug resistance and virulence profiles isolated from an Italian Hospital between 2020 and 2023. Antibiotics 13(6), 561 (2024).

Vock, I. et al. Screening sites for detection of carbapenemase-producers—a retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 13, 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-024-01513-2 (2024).

Para, O. et al. Clinical implications of multi-drug-resistant organisms’ gastrointestinal colonization in an internal medicine ward: The Pandora’s box. J. Clin. Med. 11(10), 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102770 (2022).

Jiang, H., Pu, H. & Huang, N. Risk predict model using multi-drug-resistant organism infection from Neuro-ICU patients: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 13, 15282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42522-2 (2023).

WHO/ECDC Report. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2023 Annual Report (2023).

World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report (World Health Organization, 2022).

HEALTH. 10 elements of a high-performing infection prevention program (2021).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Athena Myrou, Stavros Savvakis and Irini Georgopoulou. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Athena Myrou and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. According to national regulations, ethics committee approval was not required for non-interventional infection control surveillance studies that do not involve identifiable personal data or patient interventions.

Consent to participate

This study was conducted as part of routine hospital infection control surveillance. All data was collected anonymously, and no interventions were applied to patients. According to national regulations, informed consent was not required for participation in non-interventional observational studies involving infection control measures.

Consent to publish

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form (including individual details, images, or videos). Therefore, consent for publication is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Myrou, A., Savvakis, S., Kiouli, C. et al. Active surveillance of multidrug-resistant organism colonization in a tertiary hospital in Northern Greece. Sci Rep 15, 40280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24140-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24140-2