Abstract

This work investigates the design of a frequency selective rasorber (FSR) operating in L, S, and C bands with an absorption-transmission-absorption response, characterized by a wide transmission window. The FSR structure comprises a three-layer FSS stack-up with two air gaps in between, presenting a considerably reduced thickness of 31.275 mm (0.156λL, free space wavelength at the lowest operating frequency). The design process exploits an equivalent circuit analysis supported by accurate numerical simulations, providing comprehensive guidelines and optimizing the computational burden. Accurate numerical simulations and measurements on fabricated PCB prototypes were carried out, and a satisfying agreement was obtained. The proposed FSR solution achieves a -3 dB transmission window from 2.75 to 5.55 GHz, i.e. a 68% fractional bandwidth. Conversely, the −10 dB absorption bands extend from 1.5 to 2.75 GHz for the lower absorption band (LAB), and from 5.55 to 8 GHz, for the upper absorption band (UAB), with an overall 137% fractional bandwidth for the − 10 dB reflection coefficient. Additionally, the structure shows stable performance for oblique incidences up to 30° and achieves the widest transmission bandwidth with the thinnest electrical profile among previous literature results. These remarkable capabilities will help advancing the FSR state-of-art, promising significant contributions to applications spanning from electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding to low-observability antenna systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frequency selective rasorbers (FSRs) are multifunctional metasurfaces that exhibit electromagnetic (EM) transparency in certain frequency bands and absorption properties in others1.

Recently, FSRs are thriving due to their broad range of potential applications, from electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding for communication systems to radar cross-section (RCS) reduction in stealth platforms. In particular, electromagnetic interference (EMI) can disrupt the functioning of sensitive devices, thereby affecting the performance of the whole system. Conversely, low observability antennas configurations can significantly benefit from FSRs, preserving communication capability while lowering the radar signature. To obtain this complex response, FSRs structure encompasses both frequency selective surfaces (FSSs) and circuit analog absorbers (CAAs)2,3,4. If standalone employed, absorbers block all transmissions, effectively isolating the system from external signals. In contrast, FSSs allow signals within their passband to transmit while completely reflecting out-of-band interference, potentially interfering with other devices and producing scattering hot spots. Due to their unique properties, FSRs overcome these limitations, resulting in a prominent area of research within the electromagnetic community.

In details, a functional classification for FSRs can be performed according to the relative position of the transmission and absorption bands, resulting into three main categories. These include the transmission band below the absorption (T-A)5,6,7 the transmission band above the absorption (A-T)6,8,9 and the transmission band inserted among two absorption regions (A-T-A). In5,6 T-A and A-T arrangements are initially examined individually as independent functional layers before being cascaded into an A-T-A arrangement. In particular,6 showcases an A-T rasorber that employs the harmonic suppression principle to generate a multi-octave low insertion loss (IL) transmission window above the lower absorption band. Zhu et al. in8 present an A-T FSR exhibiting an ultrawide absorption band. This structure is developed by relying on the equivalent circuit approach, thus providing effective design guidelines for lossy dual-layer FSR design. In recent years, given the increasing demand for wideband operation in antennas used for radar and communication systems10, FSRs with a broad transmission passband and dual absorption bands, crucial for enhancing the survivability of stealth platforms in complex detection environments, are flourishing11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Additionally, FSRs can be also classified according to their structures and implementation principles, i.e. two-dimensional (2-D), 2.5-dimensional (2.5-D), and three-dimensional (3-D)22,23,24,25,26. Within these categories, 3-D FSRs exhibit a wider passband and better oblique performance at the cost of thicker profile, higher cost, and complex construction, making them impractical under space constraints or for conformal deployment.

Besides the mentioned wideband operation, also polarization insensitivity and angular stability are key performance indicators for FSRs evaluation. Currently, methodologies for designing FSRs with enhanced angular robustness revolve around unit-cell miniaturization. This approach has proven to be highly effective in mitigating response degradation when the structure is subjected to significant incidence angles, as demonstrated in27,28,29,30,31,32. Instead, dual-polarization capability, as emphasized in33,34,35,36,37,38, plays a critical role in enhancing the versatility of rasorbers, unlocking a wide range of applications and operative scenarios.

Finally, more recent works have proposed actively reconfigurable rasorbers, broadly categorized into tuneable and switchable types, each with distinct operational characteristics and design challenges39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

In this general context, the renewed growing interest towards L-S-C band radars, especially in the military sector, has dramatically intensified the demand for FSRs with low-frequency stealth capabilities. Despite this, the availability of low frequency rasorbers remains scarce due to the inherent design complexity.

Indeed, although some of the above-mentioned solutions presented in the literature perform satisfactorily in higher frequency bands, they are not easily scalable to lower frequencies. As a matter of fact, the conventional scaling factor widely used in applied electromagnetics is not reliable for multilayer media including metasurfaces. Therefore, a new design procedure must be adopted.

To address this gap, this manuscript proposes a novel A-T-A FSR that simultaneously enables broadband transmission and dual-band absorption across the L-S-C band. To the best of our knowledge, the proposed FSR sets a new benchmark in the state of the art by achieving a transmission fractional bandwidth at least 15% wider than previously reported designs5,8,9,34. This substantial enhancement makes it exceptionally suited for modern wideband applications in low-frequency stealth systems. In contrast, the FSR in8 supports only a single absorption band from the L-band upward and restricts its transmission to the X-band, limiting its use in L-S-C applications. Similarly, designs in34,47 operate in the L-S bands but exhibit narrow transmission bandwidths, thus lacking suitability for broadband scenarios. In addition, unlike prior literature solutions, the proposed work introduces a fully traceable and systematic design methodology, including a step-by-step synthesis process supported by a dedicated equivalent circuit model (ECM) and reproducible design guidelines, ensuring seamless adaptation to platform specific requirements.

Finally, the proposed structure guarantees continuous low-reflection behaviour across the L-S-C bands and features a miniaturized unit-cell, further enhancing its suitability for practical deployment and space constrained surfaces. Combined with the wide transmission bandwidth, dual-band absorption, and rigorous design methodology, these features enable integration into a broad range of low-frequency stealth platforms, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), naval systems, and ground-based radar installations.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the Design Methodology section, a description of the investigated structure is presented, along with the equivalent circuit model analysis. The Experimental Validation section reports the numerical results obtained through accurate full-wave simulations and confirmed by experimental validations. Finally, concluding remarks are drawn in the Discussion and the Conclusion sections.

Design methodology

Figure 1a illustrates the ideal frequency response of the proposed A-T-A FSR, which presents two absorption bands, respectively at lower frequency \({f}_{1}\) and higher frequency \({f}_{3}\). Amid the absorption bands, the rasorber originates a transmission window centered at \({f}_{2}\). The structure comprises three FSS layers each with peculiar functionalities, opportunely engineered to provide a polarization insensitive, low profile, wide bandpass, and angularly stable FSR. The functioning pictorial diagram of the A-T-A FSR is shown in Fig. 1b. The electromagnetic wave impacts on the structure from the top direction. In the lower band at \({f}_{1}\), the top layer has a low-pass transmission window. Since the bottom layer acts as a band-pass filter centered at \({f}_{2}\), it provides a strong reflection at \({f}_{1}\). Therefore, it represents a suitable ground plane for the lossy middle layer, achieving absorption at \({f}_{1}\). In the transmission window at \({f}_{2}\), all the three layers work together to provide the transparency response. Finally, in the higher band at \({f}_{3}\), both the bottom and middle layers act as reflective ground planes for the top lossy layer, ensuring absorption at \({f}_{3}\).

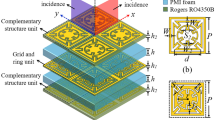

The corresponding FSR unit cell CAD model is shown in Fig. 2.

All the design process and numerical simulations have been performed with CST Microwave Studio (Dassault Systemes, France). The unit-cell presents an overall periodicity \(p\) = 24 mm and a thickness of d = 31.275 mm. The top layer is etched on a \({t}_{1}\) = 0.1 mm thick ISOLA I-Tera MT40 dielectric substrate (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 3.45, tan \(\delta\) =0.0031, depicted in green). Below it, the other lossy layer consists of two identical and orthogonal FSSs loaded with resistors and etched on the opposite sides of a \({t}_{2}\) = \({t}_{3}\) = 0.5 mm thick FR4 dielectric substrate (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 4.3, tan \(\delta\) =0.002). The bottom layer has the same middle layer geometry, but it is lossless. An air gap of \({h}_{1}\) = 20 mm is enclosed between the middle and the bottom layers, while an air gap of \({h}_{2}\) = 10 mm separates the top from the middle layer. The substrate materials were selected not only for their structural functionality in each FSS layer but also for their impedance loading effect on the FSS unit cells, making them an integral part of the overall rasorber design to achieve the intended performance.

In the following, a detailed discussion about the design strategy and the analysis with the equivalent circuit model for each FSR layer is developed.

Upper absorption band layer

The Upper Absorption Layer (UAB Layer) is designed to enable an absorption band for the frequency range above the band-pass at f2 (f3 with respect to Fig. 1). The stand-alone absorber is first analyzed to assess its absorption performance. Therefore, a metal-grounded air substrate \({h}_{2}\) = 10 mm thick is placed beneath the FSS configuration, as shown in Fig. 3a, and the reflection coefficient is numerically evaluated with periodic boundary conditions and for a normally impinging plane wave. For subsequent fabrication purposes, we already considered at this stage the periodic unit-cell etched with a 35 μm thick copper on the top side of a \({t}_{1}\) = 0.1 mm thick ISOLA I-Tera MT40 dielectric substrate (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 3.45, tan \(\delta\) =0.0031). The basic FSS shape is a cross interrupted in the central region by four 0.5 mm wide gaps. These gaps host four corresponding resistors of \({R}_{1}\)= 46.4 Ω. The values of the resistors are determined through a parametric analysis aided by circuital modelization aimed at achieving the desired absorption behavior. The geometrical parameters of the UAB layer unit-cell are reported in Fig. 3b. At this point, the reflection coefficient is numerically evaluated, and the results are shown in Fig. 3c, showing a − 10 dB absorption band spanning from 5.5 to 7.2 GHz. Physical considerations based on the transmission line equivalent circuit model (ECM) prove highly beneficial in determining effective design guidelines for FSRs. The real and imaginary components of the UAB FSS impedance are depicted in Fig. 4a. The UAB FSS acts as a capacitor in the lower frequency range (where it behaves as a transparent medium in the FSR full structure, Fig. 1) but, after the resonance, its impedance changes to inductive. Therefore, the response can be modelled through a series RLC circuit, as expressed in (1):

The transmission line schematic representation of the UAB FSS is shown in Fig. 4b.

The overall input impedance is equal to the parallel connection between \({Z}_{UAB}\) and the grounded substrate impedance \({Z}_{g}\):

where \(\beta\) is the propagation constant within the substrate medium and \({Z}_{m}^{TE,TM}\) is its characteristic impedance. Therefore, by starting from a preliminary numerical simulation and exploiting (1)-(3), the value of the real component of the \({Z}_{UAB}\) alone is determined by:

Instead, considering the imaginary part of \({Z}_{UAB}\) alone as an LC series, we can adopt the following procedure to retrieve the values of \({L}_{UAB}\) and \({C}_{UAB}\). By computing the derivative with respect to \(\omega\) of \(\mathcal{I}\mathcal{m}\left({Z}_{UAB}\right)\) and evaluating it at \({\omega }_{res,UAB}\), i.e. the resonance frequency (approximately 7.8 GHz, Fig. 4b), \({L}_{UAB}\) can be obtained:

Consequently, the value of \({C}_{UAB}\) is established from the resonance condition:

Figure 4a features the superposition of the numerical obtained and the ECM reconstructed curves, confirming the accuracy of the ECM retrieval procedure. This results in a UAB layer impedance characterized by \({R}_{UAB}=262\Omega\), \({L}_{UAB}=14 nH\), \({C}_{UAB}=0.0287 pF\). Once the lumped parameters are determined, they can be used to easily guide the numerical simulations towards the desired performance by opportunely acting on the FSS geometry.

Lower absorption band layer

The Lower Absorption Layer (LAB Layer) is meant to dissipate the impinging electromagnetic waves around f1 (Fig. 1). It comprises two lossy FSSs placed on the opposite sides of a \({t}_{2}\) = \({t}_{3}\) = 0.5 mm thick FR4 dielectric substrate (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 4.3, tan \(\delta\) =0.02). As for the UAB, also the LAB layer is examined as a stand-alone absorber to evaluate its absorption response. Thus, a grounded air substrate \({h}_{1}\) = 20 mm thick is positioned beneath the configuration, as shown in Fig. 5a. The low frequency range (L-band) requires substantial miniaturization of the unit cell to prevent grating lobes onset in the upper C-band. Large periodicity in FSS can lead to higher-order harmonics and unwanted interference, reducing overall effectiveness. Therefore, this unit-cell is engineered employing a meandering approach to increase its electrical length, thus achieving a reduced periodicity with low frequency operation. Besides grating lobes avoidance, this approach enhances also the robustness against increasing wave incidence angles. In detail, the FSS shape features a meandered I-shaped unit cell, etched on the top and on the bottom side of the FR4 substrate, but respectively 90° rotated to cover both TE and TM polarizations. The two FSS layers are interrupted by a 0.5 mm wide gap, conceived to host one corresponding \({R}_{2}\)= 130 Ω resistor to confer the absorptivity property. Geometrical parameters of the unit cell are reported in Fig. 5b. The numerically retrieved reflection coefficient for a normal impinging plane wave is shown in Fig. 5c, indicating a narrow − 10 dB absorption bandwidth spanning from 1.3 to 1.7 GHz. This is expected, since the LAB standalone impedance does not consider the contribution conferred by the other FSR layers through the unavoidable coupling and required to guarantee the desired absorbing performance. By replicating the same procedure reported for the UAB layer, real and imaginary parts of the standalone \({Z}_{LAB}\) can be extracted (Fig. 6a). In the frequency interval from 1 to 3 GHz, the FSS unit cell can be recognized as an LC series (Fig. 6b), which constitutes the first branch of the ECM and can be expressed as in (7):

At this point, \({L}_{LAB}\) and \({C}_{LAB,1}\) can be calculated with the same Eqs. (5) and (6). By moving upward within the frequency range, the retrieved LC series is to be positioned in parallel with a capacitance indicated as \({C}_{LAB,2}\) and with a resistance \({R}_{LAB}\). The value of \({R}_{LAB}\) can be directly evaluated at the parallel resonant point, as in the following expression:

Finally, the value of \({C}_{LAB,2}\) can be now computed calculating the value of \({Z}_{LAB,1}\) at \({\omega }_{res,LAB,2}\), i.e. the parallel resonance frequency, when the series \({Z}_{LAB,1}\) acts as an inductance:

The overall resulting \({Z}_{LAB}\) deducted from the analyzed ECM can be expressed as:

where \({Z}_{1}^{p}\) and \({Z}_{2}^{C}\) are specified in (12) and (13):

Figure 6a features also the comparison between the imaginary component of \({{\varvec{Z}}}_{{\varvec{L}}{\varvec{A}}{\varvec{B}}}\) obtained from full wave simulations and reconstructed via ECM, confirming the accuracy of the ECM retrieval procedure. The resulting lumped parameters for the LAB impedance are \({{\varvec{R}}}_{{\varvec{L}}{\varvec{A}}{\varvec{B}}}=2.06\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{k}}\boldsymbol{\Omega }\), \({{\varvec{L}}}_{{\varvec{L}}{\varvec{A}}{\varvec{B}}}=31.2\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{n}}{\varvec{H}}\), \({{\varvec{C}}}_{{\varvec{L}}{\varvec{A}}{\varvec{B}},1}=0.209\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{F}}\), \({{\varvec{C}}}_{{\varvec{L}}{\varvec{A}}{\varvec{B}},2}=0.0677\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{p}}{\varvec{F}}\). Again, once the lumped parameters are retrieved, it is straightforward to understand the direction required to customize the FSS response in terms of numerical CAD model geometrical optimization.

Transmission layer

As briefly described in the beginning of the section Design Methodology, a \({t}_{2}\) = \({t}_{3}\) = 0.5 mm thick FR4 dielectric substrate is adopted for this layer, etching two lossless, identical but 90° rotated versions of the same meandered I-shaped unit cell, for a polarization independent response. Geometrical parameters are listed in Fig. 5b. Incorporating meandering patterns introduces additional capacitance and inductance along the trace, enhancing its ability to pass a wide range of frequencies with minimal attenuation. In addition, this configuration is meticulously designed by considering the proximity between the FSS layers, separated by an ultrathin dielectric substrate, leading to the manifestation of a parallel LC behavior necessary for achieving the bandpass filter’s functionality.

By considering the transmission performance of the standalone lossless layer, the corresponding filtering response for a normally impinging plane wave is reported in Fig. 7a. As evident, a wideband behavior is achieved, with the − 3 dB transmission band extending from 2 to 6.6 GHz, meaning a fractional bandwidth exceeding 105%. The Insertion Loss level is approximately 0 dB in correspondence with the passband central frequency, confirming its excellent performance.

Since the geometry of the Transmission layer is a duplicate of the Lower Absorption layer, except for the absence of the two 130 \(\Omega\) resistors and the corresponding gaps, the strategy to derive the ECM is the same. Figure 7b, depicts the diagram of the Transmission layer, while Fig. 7c reports the representation of real and imaginary parts of \({Z}_{TL}\) obtained from full wave simulations is depicted. The circuital model validity is supported by the good superposition with the full-wave curve (Fig. 7c). The retrieved values of the ECM components are: \({R}_{TL}=5.7 k\Omega\), \({L}_{TL}=41.5 nH\), \({C}_{TL,1}=0.204 pF\), \({C}_{TL,2}=0.0566 pF\).

A-T-A rasorber implementation

Finally, the unit cell of the overall rasorber in A-T-A configuration is constructed by cascading the two absorbing and the transmitting layers. As a result, the conductive ground plane of the UAB layer is substituted with the LAB layer, while the lossless Transmission layer replaces the ground plane of the LAB layer, as indicated in Fig. 1b. The high-impedance condition, associated with the parallel resonance in the structure, enables passband operation while the series resonances allow absorption in the stopbands.

Numerical simulations assuming a plane wave impacting on the top layer of the FSR with different incidence angles (from 0° to 30°), and for TE/TM polarizations were performed. In particular, reflection and transmission coefficients of the designed FSR under a TE polarized plane wave for different incidence angles are reported in Fig. 8a. As expected, under normal incidence, the rasorber showcases a transmission band (|S21|> -3 dB) that covers the frequency range from 2.75 to 5.55 GHz, corresponding to a 67.5% fractional transmission bandwidth and exhibiting a very flat response. At 3.85 GHz, a minimum insertion loss of − 1.2 dB is achieved. Conversely, the Lower Absorption Band layer (LAB, |S11|&|S21|< -10 dB) spans from 1.5 to 2.75 GHz, meaning a 58.8% fractional absorption bandwidth. As for the Upper Absorption Band layer (UAB, |S11|&|S21|< -10 dB), it ranges from 5.55 to 8 GHz, achieving a fractional absorption bandwidth of 36.2%. It is worth noting that no significant degradations are observed within the transition bands from absorbing to transmitting behaviors. The presence of the two lossy layers effectively suppress reflection in the transition band to below − 10 dB, achieving a continuous low-reflection bandwidth spanning from 1.5 to 8 GHz with a fractional bandwidth of 136.8%. The exception is at 5.2 GHz, where the reflection reaches − 9.5 dB. Meanwhile, the transmission band remains largely unaffected. As the angle of incidence increases up to 30°, the transmission coefficient remains above -3 dB in the overall transparency bandwidth, proving a very stable behavior. Similarly, also very good absorption stability is observed, except for a slight reduction at 30° in correspondence of 2 GHz.

The same analysis is conducted for the TM polarization hypothesis, with the corresponding results displayed in Fig. 8b. Notably, due to the symmetry of the proposed unit-cell, TM polarization shows consistent behavior. Indeed, the reflection and transmission coefficients are coherent with respect to the results obtained for TE polarization.

The definition of the ECM for the whole FSR in the A-T-A configuration is derived by cascading the ECMs of its constituent layers. The layers are therefore separated by free-space dielectric substrates with thicknesses \({h}_{1}\) and \({h}_{2}\), modeled as equivalent transmission lines characterized by specific lengths \({h}_{1}\) and \({h}_{2}\) and relative permittivity \({\varepsilon }_{r}=1\). The ECM diagram is depicted in Fig. 9a. Consequently, it is reasonable to express:

The obtained expression of \({Z}_{ATA}\) is employed to derive the ECM-retrieved reflection coefficient of the overall FSR rasorber with the following formulation:

The expression in (19) is compared with the reflection coefficient obtained from full-wave simulations when a normal incident wave impinges on the top layer of the FSR. This comparison is reported in Fig. 9b, proving the efficiency of the Equivalent Circuit Modelization strategy.

Experimental Validation

Fabrication of the FSR

To validate the proposed design, an FSR experimental prototype with a size of 31.8 cm × 31.8 cm was fabricated. Since the three FSSs layers share the same periodicity, they were all implemented by printing a 12 × 12 array of unit cells on the designated dielectric substrates through PCB technology. As specified in Section II, ISOLA I-Tera MT40 (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 3.45, tan \(\delta\) =0.0031) was used for the Upper Absorption layer, while FR4 (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\) = 4.3, tan \(\delta\) =0.002) for the remaining ones.

The SMD resistors were in the 0603 package and were soldered on each unit cell accordingly to the design choices reported in Sect. 2. The single layers of the fabricated A-T-A FSR prototype are reported in Fig. 10a, b, and c. They were finally assembled and inserted in the measurement set-up as shown in Fig. 11a. Nylon screws were used as mechanical support for the dielectric substrates and to control the spacing distance between the layers.

Measurements Results

The measurement procedure described in25 was applied to acquire the transmission/reflection coefficients describing the FSR behavior. The measurement set-up is shown in Fig. 11b. Experimental measurements were performed in a semi-anechoic environment, where a pair of horn antennas (1–9 GHz) connected to a calibrated Vector Network Analyzer (N9918A 26.5 GHz FieldFox Vector Network Analyzer, Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) were used as transmitter and receiver, respectively. In particular, to attain the transmission coefficient, the two antennas were placed on both sides of the prototype, equally spaced from it by 60 cm. The measurements with a specific angular inclination were carried out by positioning the antennas according to the required orientation. Conversely, to characterize the absorption capability of the FSR, reflection measurements were carefully conducted by placing the two horn antennas on the same side of the panel, always maintaining the same 60 cm distance.

Experimental results of reflection and transmission coefficients of the FSR under a TE polarized plane wave are illustrated on Fig. 12a. The − 10 dB reflection band ranges from 1.61 to 8 GHz, with a fractional bandwidth of 133%. Conversely, the -3 dB transmission fractional bandwidth achieves 65.5%, covering the 2.57–5.07 GHz band. Similarly, the overall absorption performance at out-of-band frequencies results as expected, with the LAB spanning from 1.5 to 2.75 GHz, corresponding to a 58.8% fractional absorption bandwidth, and the UAB ranging from 5.55 GHz to 8 GHz, achieving a fractional absorption bandwidth of 36.2%. Finally, the FSR behavior for variable incident angles well matches the numerical simulation results, with a considerable angular stability up to 30°.

The above observations can also be confirmed for TM polarization, as depicted in Fig. 12b, further validating the dual-polarized nature of the proposed structure. The minor discrepancies from the numerical simulations can be mainly attributed to the susceptibility of the measurement results to environmental influences.

Discussion

A comparison with relevant literature about similar FSRs configurations is summarized in Table 1.

The comparison confirms a superior performance of the designed FSR in terms of both thickness and angular stability with respect to the state-of-the-art, with competitive advantages concerning the transmission fractional bandwidth (FBW). The FSRs properties in terms of physical dimensions were specifically evaluated by introducing the Effective Medium Ratio (EMR), which quantitatively reflects the unit-cell compactness and level of miniaturization:

where \({\lambda }_{L}\) is the free space wavelength at the lowest operating frequency, and \(p\) is the periodicity of the unit-cell.

Although the FSR in7 exhibits a wider transmission bandwidth, no information is provided regarding its angular stability. Moreover, the higher frequency range used in that case facilitates the design in correspondence of both the lower absorption band and the transmission window. Only the A-T-A FSRs proposed in34,36 offer superior angular stability, but with narrower transmission bandwidth. Finally, even though the proposed structure comprises two lossy layers, the overall thickness is comparable to other works, and even smaller than5,7. Only the rasorber in18 exhibits a smaller thickness; however, the transmission bandwidth is reduced, and the Effective Medium Ratio (EMR) is lower, and no angular stability is provided. The A-T-A structure in30 demonstrates superior compactness performance, while still achieving a reduced transmission band (FBW).

Therefore, the proposed FSR demonstrates a clear advancement over the current state of the art, offering a distinctive combination of wide transmission bandwidth, continuous low-reflection performance across the L, S, and C bands, and a highly miniaturized unit-cell design. These attributes effectively overcome key limitations of existing approaches, paving the way to relevant advancements in electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding and low-observability antenna systems.

Conclusion

In this manuscript, a frequency selective rasorber (FSR) in A-T-A configuration for wideband transmission and dual-band absorption in L-S-C bands was presented and analyzed. The FSR comprises a three-layer Frequency Selective Surface (FSS) structure, with two lossy layers loaded with lumped resistors, and a lossless passband layer. The design procedure was discussed sequentially, describing each layer through a transmission line equivalent circuit analysis. The Equivalent Circuit Model (ECM) was derived, offering general design guidelines for the development of wideband FSRs. The FSR was subsequently fabricated exploiting PCB technology, and its performance carefully characterized. The proposed FSR achieves a substantially extended reflection suppression band spanning from 1.5 to 8 GHz, while simultaneously maintaining a low insertion loss and wide transmission window within the S-C bands.

Both simulation and experimental results demonstrate that the proposed dual-polarized rasorber effectively meets the intended performance criteria.

This work, due to its attributes of wide passband, low profile, polarization insensitivity, and angular stability, holds significant potential in the field of low-frequency stealth capabilities.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Han, J. Y., Chang, Y. & Che, W. Frequency-selective rasorbers: a view of frequency-selective rasorbers and their application in reducing the radar cross sections of antennas. IEEE Microw. Magaz. 23(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1109/MMM.2021.3125463 (2022).

Ardeshana, M. A., Thakkar, F. N. & Domadia, S. G. Composite structure design for broadband metamaterial absorption: integrated nonlinearity and enhanced performance using lumped resistors. J. Appl. Phys. 137(9), 093104 (2025).

Hakim, M. L. et al. Triple-band square split-ring resonator metamaterial absorber design with high effective medium ratio for 5G sub-6 GHz applications. Nanomaterials 13(2), 222 (2023).

Ardeshana, M. A., Thakkar, F. N. & Domadia, S. G. Robust multi-band dng metamaterial absorber for GPS (L1), ISM, and 5G application with enhanced polarization and angle stability. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 610, 172554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2024.172554 (2024).

Ye, H. et al. A frequency-selective surface rasorber based on four functional layers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69(5), 2768–2778. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.3028215 (2021).

Chen, Y., Wan, G., Ma, X., Fu, B. & Jiao, X. Frequency-selective rasorber for wideband transmission based on hybrid resistive sheet with harmonic suppression. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 66(4), 1087–1093. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2024.3377719 (2024).

Chen, Y., Wan, G., Ma, X., Fu, B. & Jiao, X. A multilayer frequency-selective rasorber for wideband transmission based on harmonic suppression. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 66(6), e34224 (2024).

Zhu, S. et al. On the equivalent-circuit-based design of double-lossy-layer wide transmissive rasorbers with ultrawide reflection suppression band. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 72(6), 4999–5010. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2024.3388668 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Miniaturized lossy-layer scheme for designing a frequency selective rasorber. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 21(12), 2472–2476. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2022.3197449 (2022).

Wu, K., Xu, W., Yang, Y. & Li, P. A dual-polarized C-X-Ku-band frequency-selective rasorber with wide high-transmission passband. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 66(4), 1295–1299. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2024.3386530 (2024).

Li, R. et al. A method for designing multi-band rasorbers for wideband applications. IEEE Access 9, 47365–47371. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3068499 (2021).

Guo, T., Guo, M., Jia, X., Chen, Q. & Fu, Y. An absorptive frequency selective reflector with wide reflection band. IEEE Access 8, 124217–124222. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2971010 (2020).

Yin, J. et al. Broad-passband rasorber with ultra-wideband absorption incorporating graphene-based resistive films and via-based winding inductors. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2024.3440319 (2024).

Jia, Y. et al. Design of a hybrid frequency selective rasorber with wideband reflection suppression. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 22(2), 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2022.32095494R (2023).

Xia, J. et al. Design of a wideband absorption frequency selective rasorber based on double lossy layers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 68(7), 5718–5723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2019.2963585 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Broadband absorptive frequency-selective rasorber based on multilayer resistive sheets using multilayer resonator. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 70(3), 2009–2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2021.3111215 (2022).

Chen, Q., Sang, D., Guo, M. & Fu, Y. Miniaturized frequency-selective rasorber with a wide transmission band using circular spiral resonator. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67(2), 1045–1052. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2018.2880043 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Frequency-selective rasorber with a wide high-transmission passband based on multiple coplanar parallel resonances. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 19(2), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2019.2962223 (2020).

Xing, Q., Wu, W., Yan, Y., Zhang, X. & Yuan, N. A wideband frequency-selective rasorber with rectangular spiral resonators. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 21(8), 1688–1692. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2022.3177740 (2022).

Ge, J., Jiang, W., Hong, T., Gao, Y. & Gong, S. Bandpass frequency-selective rasorber with wide transmission band and high selectivity based on multiorder resonance. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 71(12), 9621–9632. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3311228 (2023).

Guo, M., Chen, Q., Bai, T., Wei, K. & Fu, Y. Wide transmission band frequency-selective rasorber based on convoluted resonator. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 19(5), 846–850. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2020.2981836 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. 3D band-absorptive frequency selective rasorber: concept and analysis. IEEE Access 7, 2520–2528. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2886967 (2019).

Yu, Q. et al. Miniaturized wide-angle rasorber with a wide interabsorption high transparent bandpass based on multiple 2.5-D resonators. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 21(2), 416–420. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2021.3134567 (2022).

Yu, Q. et al. A highly selective rasorber with ultraminiaturized unit based on interdigitated 25-D parallel resonator. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 64(5), 1585–1592. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2022.3176131 (2022).

Yang, Z., Jiang, W., Huang, Q. & Hong, T. A 2.5-D miniaturized frequency-selective rasorber with a wide high-transmission passband. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 20(7), 1140–1144. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2021.3073777 (2021).

Li, M. & Shen, Z. Hybrid rasorber based on 3-D bandpass frequency-selective structures. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 23(12), 4882–4886. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2024.3477934 (2024).

Shi, R., Yu, S. & Kou, N. A miniaturized frequency-selective rasorber with absorption bands on two sides of passband for antenna dome. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 21(11), 2161–2165. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2022.3187958 (2022).

Zhang, X., Wu, W., Huang, L., Ma, Y. & Yuan, N. Design of dual-absorptive-bands frequency selective rasorber with minkowski loop arrays. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 18(9), 1843–1847. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2019.2931432 (2019).

Yu, W. et al. Dual-polarized band-absorptive frequency selective rasorber using meander-line and lumped resistors. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67(2), 1318–1322. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2018.2883643 (2019).

Guo, Q., Su, J., Li, Z., Song, J. & Guan, Y. Miniaturized-element frequency-selective rasorber design using characteristic modes analysis. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 68(9), 6683–6694. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.2986640 (2020).

Zargar, M. M., Rajput, A. & Saurav, K. Miniaturized design of dual transmission frequency selective rasorber with wide angular stability. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 5(4), 922–932. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJAP.2024.3382834 (2024).

Sharma, A., Malik, S., Ghosh, S. & Srivastava, K. V. A miniaturized frequency selective rasorber with independently regulated selective dual-transmission response. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 21(2), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2021.3127106 (2022).

Han, Y., Zhu, L., Chang, Y. & Li, B. Dual-polarized bandpass and band-notched frequency-selective absorbers under multimode resonance. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 66(12), 7449–7454. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2018.2870274 (2018).

Xiu, X., Che, W., Yang, W., Han, Y. & Xue, Q. Double-polarized dual-passband absorptive frequency-selective transmission structure. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 62(5), 1951–1960. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2019.2954533 (2020).

Guo, M., Chen, Q., Sang, D., Zheng, Y. & Fu, Y. Dual-polarized dual-band frequency selective rasorber with low insertion loss. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 19(1), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2019.2956230 (2020).

Parameswaran, A., Kundu, D. & Sonalikar, H. S. A dual-polarized wideband frequency-selective rasorber with low in-band insertion loss and high oblique incidence stability. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 63(6), 1820–1828. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2021.3072912 (2021).

Zhou, J., Yu, S. & Kou, N. A frequency selective rasorber with absorption bands on both sides of passband based on screen-printed resistive film. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 23(11), 3912–3916. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2024.3436912 (2024).

Ai, J. et al. Enhanced equivalent circuit model-aided broadband single-lossy-single-lossless-layer rasorber design with high selectivity. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2025.3525763 (2025).

Bakshi, S. C., Mitra, D. & Teixeira, F. L. Multifunctional frequency selective rasorber with dual mode and continuous tunability. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69(9), 5704–5715. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2021.3061127 (2021).

Wu, L., Zhong, S., Huang, J. & Liu, T. Broadband frequency-selective rasorber with varactor-tunable interabsorption band transmission window. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67(9), 6039–6050. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2019.2916739 (2019).

Bakshi, S. C., Mitra, D. & Teixeira, F. L. FSS-based fully reconfigurable rasorber with enhanced absorption bandwidth and simplified bias network. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 68(11), 7370–7381. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.3008615 (2020).

Jiang, B. et al. A switchable A-T-A rasorber with polarization selectivity and high roll-off characteristics. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 22(9), 2075–2079. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2023.3274766 (2023).

Zhou, Q., Zhou, H., Huang, L., Wu, Z. & Zhang, Z. A reconfigurable frequency selective rasorber with switchable transmission/reflection/absorption band. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 66(5), 1371–1381. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2024.3422830 (2024).

Bakshi, S. C., Mitra, D. & Teixeira, F. L. Wide-angle broadband rasorber for switchable and conformal application. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 69(2), 1205–1216. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2020.3044601 (2021).

Guan, M., Wang, X. F. & Chen, A. Reconfigurable multiband rasorber with identical metallic-strip-based configuration layers for coordinated absorbing/transmitting design. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 22(10), 2556–2560. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2023.3296690t (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Active frequency-selective rasorber with switchable dual operating modes. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 23(10), 3178–3182. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2024.3429505 (2024).

F. Pascarella, D. Brizi and A. Monorchio, Design of an L-S-Band Frequency Selective Rasorber for Dual-Band Absorption and In-Band Transmission, 2024 18th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Glasgow, United Kingdom, pp. 1–4 2024. https://doi.org/10.23919/EuCAP60739.2024.10501130.

Acknowledgements

Work partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Research (MUR) in the framework of the FoReLab and CrossLab projects (Departments of Excellence).

Funding

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. P. was the main contributor to this work and was responsible for developing and implementing the methods, conducting measurements, and analysis. F. P., D. B. conceived the methodology and pro-posed the application. A. M. critically analyzed the results, suggested modifications and reviewed the manuscript. D. B. was responsible for research supervision and coordination.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pascarella, F., Monorchio, A. & Brizi, D. Design of a frequency selective rasorber for wideband transmission and dual-band absorption in L-S-C bands. Sci Rep 15, 40469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24194-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24194-2