Abstract

This paper introduces the concept of magnetic metasurfaces able to perform computational tasks in the low radiofrequency regime by exploiting inductive coupling. Two different scenarios are conceived to demonstrate the capabilities of the proposed approach. The first one consists of a magnetic metasurface evaluating the linear combination with arbitrary coefficients of two input currents. Instead, the second example is meant to extract specific harmonics from a periodic input signal. Analytical models based on the circuital theory were firstly derived to properly design the computational core, i.e. the metasurface, for the above mentioned tasks. Then, the theoretical expectations were validated through accurate full-wave simulations and experimental measures carried out on fabricated prototypes. In terms of the manufacturing process, two different techniques were employed. Specifically, the solenoid unit cells used for the linear combination case were realized by appropriately winding single-strand copper wires, while the metasurface for harmonic extraction was implemented using PCB technology. Promising results were obtained, with root mean squared experimental errors not exceeding ideal computations by more than 18.3% in both the test cases. Notably, the proposed computational metasurfaces are characterized by easy and low-cost fabrication processes, and they can be reconfigured through digitally tunable capacitors, further enlarging the span of computational tasks achievable with the same hardware arrangement. Consequently, the developed technology constitutes a valid alternative within computational analog methodologies, opening the path to an innovative and effective way to perform complex calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuous development of new technologies in every scientific field is leading to dramatically increasing requirements for unconventional and fast computational systems. As the necessity of complex calculations becomes more demanding, especially for real-time and embedded applications, digital technology is not always able to fulfill the constraints of high velocity and limited power consumption with respect to the huge number of operations that must be performed.

In this sense, a promising solution can be provided by electromagnetic metamaterials, employed to guarantee fast and robust analog computations in different scenarios. In the literature, the feasibility to execute complex calculations by exploiting the exotic properties of photonic metastructures, such as solving integral equations, ordinary differential equations, or performing matrix-vector multiplications, has been widely demonstrated1,2,3,4,5,6. Photonic metastructures are suitable for performing mathematical operations literally at the speed of light by relying upon the light transmission and reflection caused by properly tuned metastructures, thus leading to the realization of rapid and accurate systems supporting the well-known digital techniques in specific tasks. Moreover, in the recent period, a great effort has been also directed towards the implementation of intelligent and cognitive metasurfaces, whose reconfigurability may unlock a significative advancement in computational field7,8,9,10,11,12. Besides, other proposed solutions involve the adoption of crossbars for the evaluation of matrix-vector multiplications for neural network applications13,14,15,16,17,18. By selecting the impedance values in the crossbar arrays, a linear combination of the input voltages can be opportunely translated into the corresponding output currents. Finally, few systems operating in the microwave regime have been implemented for operations such as matrix-vector multiplication and derivative19,20,21,22.

However, to the best of the Author’s knowledge, the adoption of magnetic metasurfaces operating in the low-frequency RF band for computational applications has not been analyzed in the literature so far. One of the advantages of employing magnetic metasurfaces in this peculiar frequency range relies on the circuital approach effectiveness to describe the overall structure23. Indeed, quantitative and analytically easily manageable parameters depending on the system geometry can be retrieved, thus providing accurate predictions and manipulation of the metasurface behavior. In the state of the art, analytical approaches based on the circuital models have already been developed and successfully applied to control the metasurfaces response in applications such as Wireless Power Transfer and Magnetic Resonance Imaging24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In addition, magnetic metasurfaces operating in the RF band, demonstrated to be effective in the propagation of slow waves, known as magneto-inductive waves,

useful in signal and power transmission31,32,33,34,35,36. Nevertheless, no computational or cognitive behavior was conferred to the metasurfaces in those works, thus limiting their impact. In addition to the circuital modelization, magnetic metasurfaces have also simple and low-cost fabrication procedures and can be dynamically reconfigured through variable loads, thus addressing photonic structures intrinsic limitations37,38,39,40,41,42.

Therefore, considering the aforementioned advantages and the actual gap in literature, the aim of this work is to investigate magnetic metasurfaces operating in the low-frequency RF band as potential candidates to support and integrate the existing computational analog devices (Fig. 1). To pursue this purpose, two different test-cases are conceived: the first model is designed to perform a linear combination of two input currents, allowing to arbitrarily select the complex coefficients of the operation, and providing an accurate output current as the calculation result; the second system is meant to extract the first N harmonics of a fundamental frequency from an arbitrary periodic input current, which are accurately transferred in amplitude and phase to N output elements. Prototypes for the linear combination model are fabricated by manually winding single strand copper wires while PCB technology is adopted to manufacture the harmonics extraction system. An assessment of their performance and practical implementation difficulties is carried out together with a comparison of the experimental results against the simulated outcomes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: firstly, the analytical models for both the conceived test-cases are derived and explained in detail. Then, numerical simulations and experimental measurements performed on systems designed according to the analytical formulation are reported. Finally, a section is devoted to the discussion of both numerical and experimental results, highlighting the limitations and possible future developments.

Results and methods

Analytical formulation

We consider metasurfaces comprised of subwavelength magnetic unit-cells represented by accurately loaded loops or spirals. In such conditions, the i-th cell self-impedance and the mutual impedance between the i-th and j-th cells can be expressed as:

where \(\:{R}_{i}\) and \(\:{L}_{i}\) are the cell resistance and inductance, \(\:{C}_{i}\) is the capacitance applied to the cell and \(\:{M}_{ij}\) is the inductive coupling coefficient between the i-th and the j-th cells.

In general, a physical system including N interacting elements can be electrically described through the circuital equations:

where \(\:{I}_{i}\) is the current flowing in the i-th element and \(\:{V}_{i}\) is the corresponding applied voltage.

By referring to the metasurface as the system, the elements in the diagonal of the \(\:Z\) matrix introduced in (3) (i.e. the unit-cells self-impedances) can be adjusted by properly selecting a capacitor that must be applied to the desired cell. On the contrary, the elements out of the diagonal (i.e. the inductive mutual coupling between unit-cells) solely depend on the geometry of the system and must be tuned through the individual unit-cell design (e.g., the spiral’s number of turns, the overall diameter and so forth), and by adjusting its relative position within the array.

Linear combination computation

Regarding the linear combination, a preliminary arrangement aimed at performing the operation was introduced in43. In this section, we present a more general and accurate analytical framework, which can lead to more complex and relevant scenarios.

To maintain the formulation simple without losing generality, let us consider a linear array made of 5 adjacent cells, as depicted in Fig. 2. External cells 1 and 2 are active, and the respective currents \(\:{I}_{1}\) and \(\:{I}_{2}\) are the system inputs. Cells 4 and 5 are passive and serve to select the linear combination coefficients. Further, we refer to the current flowing in the central cell, \(\:{I}_{3}\), as the system output, i.e. a linear combination of the inputs \(\:{I}_{1}\) and \(\:{I}_{2}\):

with arbitrary complex coefficients \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\), correctly selected through the passive cells 4 and 5.

Schematic representation of the metasurface employed to perform the linear combination. The two more external cells provide the inputs (elements 1 and 2), the central cell acts as the calculation output (element 3), and the remaining passive cells (elements 4 and 5) allow to arbitrarily select the linear combination coefficients.

The above-described array can be efficiently described through the following linear system:

It can be noticed from (5) that mutual impedances describing the interactions between more distant cells are neglected, even though the model is not theoretically limited to the coupling between strictly adjacent and next-neighboring cells pairs. Rigorously, this assumption does not hold in general, but the numerical simulations reported in the next section demonstrate that it can be verified with a properly designed cells arrangement. Furthermore, we assume that all the unit-cells are equal in terms of geometry and the distance between them (i.e., the periodicity) is identical for each element pair. Finally, the input currents are considered to be provided only by the voltage sources, without being affected by the coupling with other cells, which is valid if the following inequality holds:

As already mentioned for the mutual coupling coefficients, the numerical simulations show that it is possible to account for (6) without losing accuracy in the output results. Thus, by exploiting these designing hypotheses, the analytical formulation simplicity can be accomplished by reducing the number of parameters in the system, while at the same time preserving all the salient features of the investigated model. It is important to stress that the proposed arrangement is only one of the possible solutions to develop the desired computational kernel, and that a higher number of degrees of freedom provided by different geometries can be beneficial for obtaining even more flexible systems.

At this point, once the desired coefficients α and β are chosen, the reactance of cells 4 and 5 can be retrieved from (5). Accounting for the assumptions explained in this paragraph, closed form expressions for the required complex impedance values to be imposed in elements 4 and 5 are obtained as follows:

where \(\:{Z}_{x}\) is the mutual impedance between adjacent cells, \(\:{Z}_{y}\) is the mutual impedance between next-neighboring cells (e.g., the coupling between cell 1 and 3 with respect to Fig. 2) and \(\:{Z}_{s}\) is the self-impedance of both input cells.

Clearly, since the system is passive, the possible span of coefficients α and β is bound by the provided input power and the system ohmic losses. More in detail, the feasible coefficients couples are those requiring a real part greater than 0 for both \(\:{Z}_{44}\) and \(\:{Z}_{55}\), otherwise the system would need additional input power to perform the desired calculation.

Harmonics extraction

The second investigated application consists in the extraction of the first N harmonics, both in amplitude and phase, of a determined fundamental frequency \(\:{f}_{0}\) from a periodic input signal. Practically, the system input is a periodic current flowing in the corresponding loop while the currents relative to the first N signal harmonics of \(\:{f}_{0}\) are mapped on the N system output loops. As a matter of fact, a generic periodic current signal with a period P can be approximated as:

where \(\:{I}_{i}\) and \(\:{\phi\:}_{i}\) are, respectively, the amplitude and the phase of the i-th harmonic phasor. Thus, the conceived system must be able to identify the first N phasors \(\:{I}_{i}{e}^{j{\phi\:}_{i}}\) of the overall input signal \(\:I\left(t\right)\) provided that \(\:1/P\) coincides with \(\:{f}_{0}\). In other words, the fundamental frequency must be known to tune the system and extract the harmonics. Nevertheless, it is possible to reconfigure the system in order to recognize harmonics of signals with different periodicities.

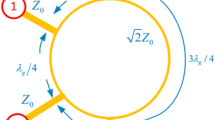

In order to implement this computational task, let us consider a single active input loop where the current periodic signal \(\:I\left(t\right)\) is flowing, N passive spirals each resonating at one specific frequency \(\:i/P\), and N passive output loops where the correct current phasor \(\:{I}_{i}{e}^{j{\phi\:}_{i}}\) must be present. Since the spirals interposed between the input and the output loops are resonating at different frequencies, they are excited only by the input harmonic at the corresponding frequency. Moreover, their Q-factor is generally quite elevated, and consequently they are not significantly affected by mutual couplings or harmonics at frequencies different from their own respective resonance. Therefore, by recurring to the superposition principle in linear systems, we can first derive a model valid for the interaction between the input loop, one resonating spiral and the corresponding output loop. Then, we can apply the same derivation for each harmonic in order to properly design the overall system. In the following analysis, the input coil, the resonating spiral, and the output coil are labelled respectively with indices 1, 2 and 3, as schematically displayed in Fig. 3 where one functional unit-cell of the overall computational metasurface is depicted.

In this case, we assume as valid the hypothesis of mutual coupling only between strictly adjacent coils, thus neglecting all others mutual impedances. In such conditions, we can write the current flowing in the resonating spiral as:

where we consider the spiral’s impedance equal to \(\:{R}_{2}\) since we are operating at its resonance frequency, while \(\:{Z}_{12}\) and \(\:{Z}_{23}\) are the spiral’s coupling coefficients with the input and output loops, respectively. Moreover, the output current can be expressed as:

where \(\:{Z}_{33}\) is the self-impedance of the output coil.

At this point, we must impose the input current equal to the output current (i.e. \(\:{I}_{1}={I}_{3}\) in amplitude and phase). This condition is effective only at the resonance frequency of the spiral 2, thus implementing the extraction of a single harmonic. Thus, by combining (10) and (11), we can retrieve the loading condition for the output loop:

Let us consider the input element 1 and the resonating element 2 to be coaxial, so that \(\:{Z}_{12}=+j\omega\:{M}_{12}\), and the output element 3 and the resonating element 2 to be coplanar, so that \(\:{Z}_{23}=-j\omega\:{M}_{23}\). As a consequence, the retrieved load to be imposed at the output loop is purely real and can be expressed as:

while the output current has the following formulation:

As evident from (14), since the factor multiplying the input current \(\:{I}_{1}\) is real, the output and input currents have the same phase. Finally, the output resistance \(\:{R}_{3}\:\)can be opportunely chosen to transfer the correct amplitude to the output element. Notably, the system must be designed in order to guarantee that \(\:{R}_{3}\) is greater than 0, namely \(\:{M}_{12}>{M}_{23}\).

Results

We realized two numerical models in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the analytical methodologies derived in the previous section. The test-cases were designed and analyzed by employing a commercial Method of Moments full wave solver (Feko Suite, Altair, Troy, MI, USA). After that, we fabricated prototypes according to the conceived scenarios in order to validate the numerical results. Regarding the experimental measurements, the impedance matrices, which completely characterize the systems, were acquired through a Vector Network Analyzer (Fieldfox series VNA N9918A, Keysight, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) and employed to evaluate the systems outputs through MATLAB. The VNA was calibrated using a SOLT 85,521 A calibration kit (Keysight, Santa Rosa, CA, USA), and the impedance matrices were derived from the measured S-parameters assuming a 50 Ω reference resistance. The input phase reference plane was established at the VNA input ports.

Linear combination computation: numerical and experimental results

The numerical model was developed by following the pictorial representation depicted in Fig. 2. Each unit-cell was conceived as a 20-turn solenoid with a diameter of 10.5 mm, a total height of 8.4 mm and realized with an AWG 28 single strand copper wire. The periodicity, i.e. the distance between the central point of two adjacent solenoids, was set equal to 14 mm. The simulations were performed at 6 MHz, thus fully respecting the quasi-static approximation. As explained in the analytical model derivation, the most external solenoids 1 and 2 serve as inputs and the corresponding currents are summed in the output central solenoid 3, opportunely weighed for the coefficients imposed by the remaining solenoids 4 and 5. More in detail, the input cells were loaded with adequate capacitors in order to resonate at 6 MHz and with resistances devised to control the desired input magnitudes. Conversely, solenoids 4 and 5 were equipped with capacitors and resistors evaluated following (7) and (8), thus implementing the desired linear combination calculation. Finally, the prototype was assembled by winding the AWG 28 wire around 3D printed cylindrical PLA supports, which were in turn mounted on a 0.8 mm thick FR4 substrate. The FR4 board was equipped with PCB etched copper paths to allow the soldering of the resistors and capacitors evaluated through the design process. A depiction of both numerical and experimental set-ups is reported in (Fig. 4a,b).

As stated in the Analytical Formulation section, physically realizable computations require that the solenoids 4 and 5 impedances evaluated through (7) and (8) present both a positive real part. Such constraint is visualized in (Fig. 5a,b) for an arbitrarily selected \(\:\alpha\:=0.7j\) and different coefficients \(\:\beta\:\).

Span of possible coefficients \(\:\beta\:\) with the arbitrarily selected \(\:\alpha\:=0.7j\) for the linear combination test case. Both impedances to be imposed in solenoids 4 and 5 (i.e. (a) \(\:{Z}_{44}\) and (b) \(\:{Z}_{55}\)) must have a positive real part, leading to feasible \(\:\beta\:\) ranging from − 0.4 to 0.

As evident from Fig. 5, regarding this specific model and for the coefficient \(\:\alpha\:=0.7j\), the set of possible choices for the coefficient \(\:\beta\:\) lies between \(\:-0.4\) and \(\:0\), where both the required impedances have a positive real part. In fact, the realizable range of output currents is limited by the dissipated power in the structure, which must be at most equal to the active power provided by the source. Attempting to achieve an output current that results in higher dissipated power would require additional energy to be introduced into the system, which is mathematically equivalent to the presence of a negative resistance. Notably, a different set-up, with a larger number of degrees of freedom, may provide different and wider sets of coefficients combinations. In fact, increasing the number of unit-cels leads to a larger N×N impedance matrix (where N is the unit-cells number), whose diagonal can be modified by applying loads to the individual unit-cells, so that the design space expands. In Fig. 6a–d, ideal, numerical and experimental linear combination outputs for 4 different coefficients combinations are reported and compared. For each combination, the input solenoids are loaded with a 15 Ω resistor and a 161 pF capacitor, while the output solenoid is equipped with a 1 Ω resistor and a 161 pF capacitor. Then, in Table 1 the capacitance and resistance values applied to cells 4 and 5 are listed.

Comparison among ideal, numerical and experimental calculation outcomes for different linear combination arrangements: (a) \(\:\alpha\:=0.7j\) and \(\:\beta\:=\)-0.2, (b) \(\:\alpha\:=0.5j\) and \(\:\beta\:=\)-0.4, (c) \(\:\alpha\:=0.3j\) and \(\:\beta\:=0.6j\), (d) \(\:\alpha\:=-0.2\) and \(\:\beta\:=\)-0.4. In general, it is possible to observe a good agreement between the ideal output and the one provided by the conceived system.

Both numerical and experimental outputs provide a valid approximation of the ideal calculation. The errors, which can be appreciated on the scatter plots in Fig. 6, are mainly caused by the influence of the couplings on the input currents in elements 1 and 2, meaning that (6) is not perfectly verified. On the contrary, couplings with cells distant more than two times the periodicity are actually negligible, as shown in the following Fig. 7. For instance, the mutual coupling between two cells distant 3 times the periodicity (i.e., 43.5 mm) is 3.3% of the strictly adjacent cells coupling and, consequently, can be neglected without significantly affecting the output accuracy.

Mutual coupling between two solenoids unit-cells adopted in the linear combination test case as a function of their respective distance. While cells placed at 2 periodicity distance (next-neighbors) are characterized by a significative coupling (10% of the coupling between strictly neighboring cells), cells distant 3 periodicities present a coupling that drops at 3.3% and can be safely neglected.

In Table 2, root mean square errors and standard deviations between experimental and ideal current outputs are reported, as evaluated with the following expression:

From Table 2, the general good agreement between ideal and experimental results, already qualitatively highlighted in Fig. 6, can be confirmed, with mean errors not exceeding 14.7% and thus fully validating the proposed approach.

Moreover, the robustness of the system to errors in practical scenarios is a critical aspect to consider. While the required impedances are derived analytically using parameters obtained from ideal full-wave simulations, a physical implementation is inevitably subject to noise, manufacturing imperfections, and tolerances in lumped components. As a result, the actual impedance values of the unit cells may deviate from their theoretical targets, potentially compromising the accuracy of the desired computation.

To evaluate this effect, we conducted a numerical robustness analysis by introducing a ± 1% variation to the self-inductances of cells 4 and 5 (mimicking fabrication issues and noise), as well as to the associated lumped resistors and capacitors (to evaluate tolerances). For each perturbed configuration, the system’s output currents were computed for 10 randomly selected input vectors, and then compared to the ideal output obtained using the nominal values. The resulting errors on the system output, expressed as root mean square errors across all coefficient pairs, are summarized in Table 3, revealing a robust behavior and proving the practical implementation feasibility.

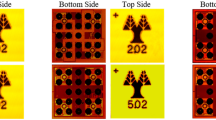

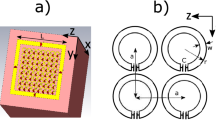

Harmonics extraction: numerical and experimental results

The numerical model conceived to demonstrate the extraction of the harmonics of a determined fundamental frequency from a periodic input signal consisted of an input loop, 8 resonating spirals, and 8 output loops (Fig. 8a). The periodic current flowing in the input loop was synthetized as a sum of 8 harmonics with a fundamental frequency equal to 5 MHz and arbitrarily selected amplitudes and phases. Thus, the system was meant to map these harmonics of the input signal (from 5 MHz to 40 MHz) on the currents flowing in the external output loops.

In detail, the input loop was placed 10 mm above the metasurface and presented a 25 mm radius. Regarding the metasurface design, the 8 resonating 5-turn spirals, that serve to transfer each harmonic to the corresponding output loop, were conceived with an inner radius of 4 mm, an external radius of 8 mm and a periodicity of 19 mm. Finally, the metasurface output loops were realized with a radius of 4 mm and a periodicity of 21 mm, positioned 1 mm externally and in a coplanar fashion with respect to the corresponding spirals. Regarding the manufacturing process, PCB technology was selected to fabricate the prototype. All the system elements were realized with a 35 μm thick copper trace. The substrate was FR4 with a 0.1 mm thickness for the metasurface, while a 0.8 mm thick FR4 was employed for the input loop (Fig. 8b). Opportune copper paths were added to allow the soldering of capacitors and resistors required according to (13) to perform the desired computational task.

In Fig. 9, we reported the currents distribution in the system for two exemplificative harmonics, i.e. 10 MHz (Fig. 9a) and 30 MHz (Fig. 9b), obtained through numerical simulations. From a visual inspection, it can be pointed out the same current amplitude between the input and output loops for the two respective harmonics, while currents do not circulate in other cells. This proves that, as described in the Analytical Formulation section, for each harmonic flowing in the input loop, only the spiral resonating at the corresponding frequency is activated. In this way, the first 8 harmonics of the input signal can be properly transferred through the superposition principle to the output loops. Moreover, the 8 harmonics imposed as input and those extracted by the computational metasurface, in terms of both magnitude and phase, are summarized in (Fig. 10a,b), comparing ideal, numerical and experimental data. Besides, Table 4 reports the root mean square errors between ideal and experimentally measured harmonics evaluated according to Eq. 15. It can be noticed that the proposed arrangement is able to effectively accomplish the planned computational task, with the maximum experimental errors equal to 11.8% (for amplitude) and 18.3% (for phase) at 25 MHz. As for the linear combination test-case, also for harmonic extraction experimental implementations, component tolerances, particularly those of the lumped loads, represent a significant source of error. Consequently, the robustness of the system to such variations is a key factor to assess. As discussed in the analytical formulation section, the resistors connected to the output loops play a crucial role in ensuring the correct transfer of harmonic magnitudes, while capacitors guarantee the filtering behaviour by providing the desired resonance frequencies. To evaluate the impact of loads tolerances, manufacturing errors and noise on harmonic extraction, we introduced a random ± 1% variation to the nominal load and self-impedance values and computed the resulting error in the extracted harmonics. The outcomes of this analysis are summarized in Table 5, confirming the excellent device robustness against the aforementioned non-idealities.

Then, Fig. 11 compares the input overall periodic signal and the reconstructed one obtained by summing the harmonics circulating in the metasurface external loops, both for simulated and experimental scenarios. Since the manufactured metasurface is characterized by higher losses with respect to the simulated structure44, the distance between the input loop and the kernel had to be reduced to 1 mm in order to guarantee a correct harmonic evaluation. This modification was necessary in order to increase the coupling between the input and the metasurface, thus compensating for the additional losses as predicted in (14). As evident, both the numerical and measured reconstructed signals are excellent representations of the ideal input current. To quantitatively verify the signals similarity, the correlation coefficients between the input signal and the numerical and experimental reconstructed signals were evaluated, resulting in 0.997 and 0.991 respectively, thus confirming the excellent performance of the arrangement. Finally, we assessed the effect of each harmonic on non-corresponding output loop by evaluating the Inter-Channel Rejection Ratio, defined as follows:

where \(\:{I}_{i}\) is the amplitude of the correct harmonic extracted in the i-th loop, and \(\:{I}_{j}\) is the amplitude of undesired harmonics circulating in the other loops caused by \(\:{I}_{i}\). The results are reported in Table 6 where an excellent independence of each output loop with respect to the others can be observed.

Discussion

In this paper, we introduced the concept of analog computing through magnetic metasurfaces in the low radiofrequency regime by exploiting inductive coupling. In particular, we developed two analytical models which can be employed for the realization of systems capable to: (i) evaluate the linear combination between two current inputs with arbitrary weighting coefficients, and (ii) extract the first 8 harmonics of a fundamental frequency from a generic periodic input current. In both cases, the analytical framework indicates the lumped loads that must be applied to each unit-cell in order to achieve the desired output. We provided numerical and experimental designs to validate the models, with simple and low-cost manufacturing techniques, which include winded copper wire solenoids for the liner combination test case and PCB printed cells for the harmonics extraction case. We obtained promising results, with experimental root mean square errors that does not exceed 15% for the linear combination model and 18% for the harmonic extraction system, thus proving the possibility to employ magnetic metasurfaces for computational purposes.

Regarding the first test case (i.e. the linear combination), we showed that the set of possible coefficients that can be chosen is limited by the impedance loading conditions, since the loads must have a positive real part. However, more complex designs involving a larger number of unit-cells and, consequently, more degrees of freedom can be explored to overcome the aforementioned limitation. Notably, linear combinations can be interpreted as scalar products between vectors, and their extension to matrix–vector multiplications is fundamental to many numerical methods. These include the approximation of equation solutions and more advanced operations such as derivatives and integrals. Therefore, the approach presented in this work can serve as a foundational step toward the development of analog computing architectures capable of implementing a wide range of numerical computations.

It must be also underlined that the fabrication procedure is of particular importance due to possible additional losses and components tolerances that may occur. In fact, in the second test case (i.e. the harmonics evaluation), an added resistor is employed to retrieve the correct harmonic in terms of magnitude and, consequently, must be realized with sufficient accuracy.

As future perspectives, an additional value of the proposed technology consists in the system dynamic reconfiguration by modifying the unit-cells reactance through the adoption of varactors, thus achieving multiple computational capabilities with the same hardware. Moreover, further studies will be directed to the improvement of system performance in terms of accuracy, leading to the possibility of realizing reliable computational devices with multifrequency capabilities through the harmonics recognition, and to the exploration of different possibilities, including large matrix-vector multiplications and equation solutions. Clearly, while larger systems may enable in principle more complex operations with multiple inputs and outputs, thereby broadening the scope of possible calculations, deeper studies are required to evaluate physical constraints and error accumulation due to fabrication tolerances and lumped-element inaccuracies—factors that are particularly critical given the resonant behavior of the proposed structures. These aspects will be addressed in future works.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Silva, A. et al. Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials. Science 343, 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242818 (2014).

Zhou, H. et al. Optical computing metasurfaces: applications and advances. Nanophotonics 13, 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0871 (2024).

Cordaro, A. et al. Solving integral equations in free space with inverse-designed ultrathin optical metagratings. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-022-01297-9 (2023).

Nikkhah, V., Mencagli, M. J. & Engheta, N. Reconfigurable nonlinear optical element using tunable couplers and inverse-designed structure. Nanophotonics 12, 3019–3027. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0152 (2023).

Cavicchioli, G., Melloni, A., Miller, D. A. B., Engheta, N. & Morichetti, F. Programmable photonic architecture solving systems of ordinary differential equations. Proc. Int. Conf. Photonics Switch. Comput. 1–3 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/PSC57974.2023.10297288

Camacho, M., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. A single inverse-designed photonic structure that performs parallel computing. Nat. Commun. 12, 1466. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21664-9 (2021).

She, Y. et al. Intelligent reconfigurable metasurface for self-adaptively electromagnetic functionality switching. Photon Res. 10, 769–776 (2022).

Geng, M. et al. Optically transparent graphene-based cognitive metasurface for adaptive frequency manipulation. Photonics Res. 11, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.472868 (2023).

Ma, Q. et al. Smart metasurface with self-adaptively reprogrammable functions. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-019-0205-3 (2019).

Liu, Y. H. et al. Incident angle sensing and adaptive control of scattering by intelligent metasurface. Adv. Sci. 11, 2406841. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202406841 (2024).

Bilotti, F. et al. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces as the key-enabling technology for smart electromagnetic environments. Adv. Phys. X. 9, 2299543. https://doi.org/10.1080/23746149.2023.2299543 (2024).

Ma, Q. et al. Information metasurfaces and intelligent metasurfaces. Photon Insights. 1, R01. https://doi.org/10.3788/PI.2022.R01 (2022).

Jain, S., Sengupta, A., Roy, K., Raghunathan, A. & RxNN A framework for evaluating deep neural networks on resistive crossbars. IEEE Trans. Comput. -Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 40, 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAD.2020.3000185 (2021).

Jung, S. et al. A crossbar array of magnetoresistive memory devices for in-memory computing. Nature 601, 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04196-6 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Assessment of functional performance in self-rectifying passive crossbar arrays utilizing sneak path current. Sci. Rep. 14, 24682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74667-z (2024).

Jeon, K. et al. Dot-product operation in crossbar array using a self-rectifying resistive device. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 2200392. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202200392 (2022).

Jeon, K. et al. Purely self-rectifying memristor-based passive crossbar array for artificial neural network accelerators. Nat. Commun. 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44620-1 (2024).

Tzarouchis, D. C., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. Programmable wave-based analog computing machine: a metastructure that designs metastructures. Nat. Commun. 16, 908. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56019-1 (2025).

Yang, H. Q. et al. Programmable wave-based meta-computer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2404457. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202404457 (2024).

Fu, P. et al. Reconfigurable metamaterial processing units that solve arbitrary linear calculus equations. Nat. Commun. 15, 6258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50483-x (2024).

Hao, L. et al. Performing calculus with epsilon-near-zero metamaterials. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq6198. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq6198 (2022).

Yang, H. Q. et al. Complex matrix equation solver based on computational metasurface. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310234. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202310234 (2024).

Brizi, D. & Monorchio, A. An Analytical Approach for the Arbitrary Control of Magnetic Metasurfaces Frequency Response, in IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 20 (6), 1003–1007 https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2021.3069571 (2021).

Dellabate, A., Lazzoni, V., Monorchio, A. & Brizi, D. Arbitrarily conformal metasurfaces for enhanced wireless power transfer systems. IEEE Access. 12, 64376–64384. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3396826 (2024).

Zhou, J., Zhang, P., Han, J., Li, L. & Huang, Y. Metamaterials and Metasurfaces for Wireless Power Transfer and Energy Harvesting. In Proceedings of the IEEE 110 (1), 31–55 https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2021.3127493 (2022).

Schmidt, R. et al. Flexible and compact hybrid metasurfaces for enhanced ultra high field in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Sci. Rep. 7, 1678. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01932-9 (2017).

Li, M., Khaleghi, A., Hasanvand, A., Narayanan, R. P. & Balasingham, I. A new design and analysis for metasurface-based near-field magnetic wireless power transfer for deep implants. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 6442–6454. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3354394 (2024).

Zahra, S. et al. Electromagnetic metasurfaces and reconfigurable metasurfaces: A review. Front. Phys. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.593411 (2021).

Rotundo, S., Lazzoni, V., Dellabate, A., Brizi, D. & Monorchio, A. Dual-Tuned magnetic metasurface for field enhancement in 1H and 23Na 1.5 T MRI. Appl. Sci. 15, 5958. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15115958 (2025).

Motovilova, E. & Huang, S. Y. Hilbert curve-based metasurface to enhance sensitivity of radio frequency coils for 7-T MRI. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 67, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2018.2882486 (2019).

Shamonina, E., Kalinin, V. A., Ringhofer, K. H. & Solymar, L. Magnetoinductive waves in one, two, and three dimensions. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 6252–6261. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1510945 (2002).

Yan, J., Stevens, C. J. & Shamonina, E. A metamaterial position sensor based on magnetoinductive waves. IEEE Open. J. Antennas Propag. 2, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJAP.2021.3057135 (2021).

Stevens, C. J. A magneto-inductive wave wireless power transfer device. Wirel. Power Transf. 2, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/wpt.2015.3 (2015).

Mishra, V. & Kiourti, A. Wearable planar magnetoinductive waveguide: A low-loss approach to WBANs. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69, 7278–7289. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2021.3070681 (2021).

Jenkins, C. B. & Kiourti, A. Wearable dual-layer planar magnetoinductive waveguide for wireless body area networks. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 71, 6893–6905. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3286042 (2023).

Jenkins, C. & Kiourti, A. Analytical model for three resonant element-based magnetoinductive waveguides. Proc. 4th URSI Atlantic Radio Sci. Meet. (AT-RASC), 1–4 https://doi.org/10.46620/URSIATRASC24/OFFA5915 (2024).

Zahra, S. et al. Electromagnetic metasurfaces and reconfigurable metasurfaces: A review. Front. Phys. 8, 593411. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.593411 (2021).

Pitilakis, A. et al. A multi-functional reconfigurable metasurface: electromagnetic design accounting for fabrication aspects. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69, 1440–1454. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2020.3016479 (2021).

Wang, H. L., Ma, H. F., Chen, M., Sun, S. & Cui, T. J. A reconfigurable multifunctional metasurface for full-space control of electromagnetic waves. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100275. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202100275 (2021).

Liao, J. et al. Independent manipulation of reflection amplitude and phase by a single-layer reconfigurable metasurface. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2101551. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202101551 (2022).

Yang, R. et al. Reconfigurable metasurface with multiple functionalities of frequency-selective rasorber, frequency-selective surface, absorber, and reflector. Adv. Mater. Technol. 10, 2400966. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202400966 (2025).

Yin, T. et al. Reconfigurable transmission-reflection-integrated coding metasurface for full-space electromagnetic wavefront manipulation. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2301326. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202301326 (2024).

Dellabate, A., Brizi, D. & Monorchio, A. Towards low-frequency reconfigurable computational magnetic metasurfaces. In: Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Antennas Propag. INC/USNC-URSI Radio Sci. Meet (AP-S/INC-USNC-URSI) 2023–2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/AP-S/INC-USNC-URSI52054.2024.10687136 (2024).

Usai, P., Brizi, D. & Monorchio, A. Low-frequency magnetic metasurface for wireless power transfer applications: reducing losses effect and optimizing loading condition. IEEE Access. 11, 66579–66586. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3291338 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Italian Ministry of Research (MUR) in the framework of the FoReLab and CrossLab Projects (Departments of Excellence).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. D. was the main contributor to this work and was responsible for developing and implementing the methods, conducting measurements, and analysis. A. D., D.B. conceived the methodology and proposed the application. A. M. critically analyzed the results, suggested modifications and reviewed the manuscript. D.B. was responsible for research supervision and coordination.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dellabate, A., Monorchio, A. & Brizi, D. Computational magnetic metasurfaces in the low radiofrequency regime. Sci Rep 15, 40856 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24629-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24629-w