Abstract

This study aimed to explore the neural basis of self-control and cognitive control by examining the brain activity during an inhibitory control task. Fifty-four participants (37 women) took part in this study. Their self-control was assessed through three psychometric scales, on the basis of which the general self-control Factor S has been extracted. Cognitive inhibition was measured using the Go / No Go task with social stimuli (emotionally significant faces), during which event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to capture the neural activity. We found that participants with high scores on Factor S showed stronger activation in the right and left Inferior Frontal Gyri, but only during trials when negative social stimuli served as inhibition cues. Medium self-control individuals showed greater Anterior Insula activity compared to other groups, in response to positive social cues. Overall, we found that strong self-control was associated with distinct and heightened neural activity during cognitive inhibition when the inhibition cue had a negative emotional valence. These findings bridge the gap between self-control and cognitive inhibitory control, emphasizing emotional context and neural mechanisms. The results align partially with previous studies while introducing structure and novelty for clinical implications and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a world where goods are abundantly available, self-control (SC) is crucial for better health, avoiding trouble, and staying free from addictions1,2,3. It is strongly related to quality of life, comparably to or even stronger than intelligence or socio-economic status1. SC supports stress management, focus, planning, and goal pursuit, while also enhancing relationships, academic success, and social mobility2,4,5,6. The negative impact of a high level of SC is minimal7. Strong SC individuals consistently pursue goals, regulate impulses effectively, and proactively engage control mechanisms. Medium SC individuals can pursue long-term goals and resist impulses, but their SC may be inconsistent. Low SC individuals tend to favor immediate gratification and show less engagement in regulatory processes8.

Although SC is often discussed alongside executive functions (EFs), it represents a distinct construct9,10. EFs are transient, task-specific cognitive operations, such as inhibition of automatic response, updating working memory, and shifting attention, that support goal-directed behavior11. In contrast, SC is a relatively stable personal trait reflecting the tendency to engage these operations in the service of long-term goals12,13,14,15. According to our preferred model, SC consists of five key components: inhibition and adjournment, switching and flexibility, goal maintenance, initiative and perseverance, and proactive control16. Behavioral SC refers to observable actions such as resisting temptation or delaying gratification, while self-reported SC captures individuals’ perceived ability to regulate impulses and maintain goal-directed behavior over time. As Walter Mischel demonstrated, behavioral SC involves cognitive strategies that depend on EFs, such as attention shifting and mentally transforming tempting stimuli3. Inhibition, often associated with successful SC, is prone to failure and is considered a last-resort mechanism when other regulatory strategies are unavailable17,18. Effective SC thus requires a strategic, anticipatory approach, engaging proactive control mechanisms during the planning phase, prior to action initiation.

There is a limited number of publications on the neural basis of SC, and those available show inconsistent results19. For example, Hare and his team found that low behavioral SC was associated with ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) activity, while participants with strong SC engaged the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), particularly the left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (LIFG)20. These results were not confirmed by a later study, when groups were based on self-report data21.

Surprisingly, performance on the commonly used EFs tasks (e.g., Go/No-Go, Stroop, Set Switching) shows little correlation with SC, whether measured behaviorally or via self-report10,12,16. These inconsistencies likely stem from several factors. First, EFs tasks often suffer from ceiling effects, especially in non-clinical samples, as they are relatively simple and may not sufficiently challenge participants, resulting in limited variability in performance. Second, SC is measured in diverse ways across studies, including self-report questionnaires, informant reports, and behavioral paradigms like delay-of-gratification tasks (e.g., the marshmallow test). These approaches tap into different aspects of SC and are not always directly comparable. Third, most studies rely on non-clinical populations, where SC levels are generally moderate to high, reducing the likelihood of detecting strong correlations. Finally, EFs tasks vary across studies, as different authors use distinct tasks that often engage multiple cognitive processes (the problem of task impurity).

Casey and her team22 found that people who control their behavior effectively activate their brains differently when engaging EFs to inhibit a well-learned action. Participants who took part in the famous Marshmallow test forty years earlier as preschoolers, were asked to complete a Go/No Go task (GNG), where they had to react (Go) or not react (No Go) to social cues (happy or fearful faces). The majority of trials required action, making non-reaction difficult. Though task performance differences were minimal, the strong SC group showed increased activity in the right IFG (RIFG) when inhibiting actions, compared to the low SC group. Low SC participants activated the ventral striatum, part of the reward system, when inhibiting their reaction to positive stimuli. SC in this study was measured based on participants’ delay time at the age of four, as well as scores on an eight-item SC scale in adulthood, which is one of this study’s limitations.

To address inconsistencies in findings on the EFs - SC relationship, we propose an adaptive control modulation model in which trait SC modulates the dynamic engagement of EFs, without being reducible to these processes. At the trait-level, SC reflects baseline differences in the threshold for engaging control systems. Individuals high in SC are more likely to proactively recruit control-related brain regions, even in the absence of observable EFs differences. At the state level, EFs’ engagement is context-dependent and dynamically engaged based on task demands, emotional salience, and motivational relevance. This engagement is modulated by trait SC, which directs attention toward goal-relevant cues, supports suppressing automatic responses conflicting with long-term goals via activation of control-related neural systems - such as the IFG. The neural instantiation of inhibition is modulated by the trait SC, which influences the efficiency, timing, and selectivity of EFs recruitment. This model aligns with Braver’s Dual Mechanisms of Control framework23, suggesting that individuals high in SC proactively recruit control-related neural systems, while those with lower SC rely more on reactive control.

The control mechanisms are particularly relevant in emotionally salient contexts, where regulation demands are heightened. According to Gross’s process model of emotion regulation, individuals must deploy cognitive control strategies, such as attention shifting or reappraisal, to modulate emotional responses, especially when stimuli are intense or socially meaningful24. Inhibitory control plays a key role in overriding automatic emotional reactions, such as those triggered by social cues. Participants exposed to emotionally valenced facial expressions exhibit automatic muscle activation consistent with the emotional content of the stimuli, even when explicitly instructed not to respond25. This underscores the reflexive nature of emotional responses and the regulatory challenge they pose. Individuals with high self-reported SC not only report lower emotional reactivity, but also exhibit stronger and more sustained functional connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal regions, suggesting a trait-driven capacity for anticipatory regulation26.

Emotional facial expressions differ in their social and motivational significance: positive cues (e.g., happy faces) signal reward and acceptance, while negative cues (e.g., fearful or angry faces) signal threat or rejection. Emotion regulation theory suggests that these cues engage distinct neural systems24,26,27. Individuals typically aim to reduce negative emotions and enhance positive ones, but also adjust emotional responses to fit situational goals, sometimes increasing negative emotions or suppressing positive ones when contextually appropriate24. Individuals with high trait SC may be more likely to engage proactive control mechanisms to manage these responses, resulting in stronger activation in control-related regions. In contrast, positive stimuli potentially elicit conflict-related circuits when a response to a smile must be suppressed to follow task demands28. In individuals with low SC, such cues may instead activate reward-related processing, such as in the ventral striatum22.

This study investigates whether cognitive control (EFs, such as inhibition) and self-control (SC) as a trait are related at the neural level, aiming to clarify mechanisms underlying effective SC. We propose that individuals with strong SC exhibit distinct and more targeted brain activity patterns during response inhibition compared to those with average or poor SC. While using the same tasks as Casey and co-authors22 to ensure consistency, we propose a more reliable

method of measuring SC by combining three well-established self-report measures and extracting their common factor using the factor analysis procedure – Factor S. We selected regions of interest (ROIs) previously linked to either inhibition or SC20,22,29.

The proposed adaptive control modulation model highlights how trait SC enhances the likelihood of proactive engagement of EFs, potentially influencing the neural patterns associated with them. We hypothesize that strong SC individuals will show increased activation in both the RIFG22,29 and LIFG20 during response inhibition tasks, especially when inhibiting fearful social cues26, which may carry implicit threat associations, even when task performance appears similar across groups8. The right IFG is widely recognized for its role in motor response inhibition, particularly in suppressing prepotent responses22,29. The left IFG, while also involved in inhibition30, is more closely linked to goal-directed decision-making and is considered to be associated with the effective SC20. Together, increased bilateral IFG activation may reflect a more robust and coordinated engagement of control processes in individuals with high SC, especially when inhibiting reactions to fear-related social cues. We also expect increased activity in bilateral AI, important for detecting task-relevant cues and conflict, especially during inhibition of positive social stimuli, amongst high and medium SC participants, due to heightened conflict between task demands and approach tendencies28,29. We predict that low SC individuals will rely more heavily on reactive control, due to a reduced tendency to engage regulatory mechanisms, showing overall smaller activation in control-related regions whilst showing greater activity in reward-related regions (e.g., ventral striatum) when withholding responses to positive social cues22.

Results

EFs task and SC measure

Participants achieved a high level of task accuracy (M = 93.83% of correct answers, SD = 4.69). Results distribution was significantly different from normal (S-W =.76, p <.001). Descriptive statistics of the accuracy per task condition and Factor S group are summarized in Table 1. The Factor S did not significantly correlate with accuracy or reaction time in any task condition. Furthermore, no significant differences in task performance were observed between the Factor S groups. This was checked across all conditions and stimulus types using Pearson’s r-correlation coefficient and the Kruskal-Wallis H test separately for each condition and stimulus type.

Neural

Main effect of the task

The inhibition effect (contrast No Go minus Go) was significant at p <.05 FWE search threshold, whole brain (WB), with k = 1. The following clusters were significantly more active: right IPL and SMG; right IFG and MFG; left IFG; left MFG and IFG; left IPL and SMG/TPJ; right STG and STS; right SFG and SMA (N = 54, p cluster <.05 FWE). Table 2 contains detailed statistics for contrast No Go minus Go. Go minus No Go contrast activity results are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Go/No go and factor S

Factor S, introduced as a covariate to the model (contrast No Go minus Go), was not significantly associated with any activation. This model included all types of emotional stimuli. To verify non-linear dependencies, we conducted a second-level ANOVA of all groups with planned comparisons. Signal strength in the three groups, distinguished based on Factor S scores, did not differ significantly from each other (search threshold p ≤.001 uncorr. WB, k = 1). We conducted separate analyses for each type of emotional stimuli.

Fearful No Go and SC

The ANOVA showed no significant group effect in the inhibition of fearful faces (No Go minus Go). To test the hypothesis, we conducted planned comparisons, which revealed greater Vermis activity in the high Factor S group compared to the medium group (t(51) = 4.35; p <.05, FWE WB; k = 40; x = 0, y = −58, z = −34). No significant differences were found in this area in other group comparisons.

The high Factor S group also showed stronger activation than the medium group in the pars opercularis of the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and AI (t(51) = 4.22; p cluster <.05 FWE WB; x = 48, y = 8, z = 2; k = 91). This area overlaps with the identified RIFG ROI from previous work by Casey et al22. Subsequent analysis was aimed at confirming the other author’s results. Notably, no significant differences were found between the low and medium or the low and high groups.

ROI

Based on the findings of Casey et al22, we examined RIFG ROI and found that the high Factor S group showed significantly greater activity than both the low (t(51) = 3.38; p cluster <.05, FWE SVC; k = 2) and medium groups (t(51) = 4.15; p cluster <.05, FWE SVC; k = 16). There was no significant difference between the low and medium groups. Figure 1 shows a graph of the signal parameter estimate and its brain location.

Following Hare et al22, we also investigated the ROI of the left IFG. The high Factor S group showed significantly greater activity than the medium (t(51) = 3.37; p cluster <.05 FWE SVC; k = 2; peak at x = −48, y = 38, z = 6) and low groups (t(51) = 3.64; p cluster <.05, FWE SVC; k = 9; peak at x = −51, y = 35, z = 10). The low and medium groups did not significantly differ from each other. Figure 2 shows the average signal estimate for each group and its location.

Happy No Go and SC

Neither the ANOVA nor the planned comparisons revealed significant differences between the groups in the No Go condition with happy faces (WB).

ROI

Focusing on the AI ROI based on Berkman et al.29, the medium Factor S group showed significantly greater activity than the high group in the left AI (x = −30, y = 17, z = −2; t(51) = 4.41; p cluster <.05, FWE SVC, k = 12). The low and medium groups did not differ significantly.

Figure 3 shows signal differences between the groups.

We also searched the ROI of the ventral striatum following Casey et al.22 but found no significant differences in activity between the groups (initial search threshold p ≤.005 uncorr., k = 1).

Discussion

While many studies do not show a relationship between executive functions (EFs) and self-control (SC)18,19, we aimed to demonstrate such a correlation at the neural level, using functional MRI. Participants completed an inhibition task involving emotional stimuli (fearful and happy faces), replicating the paradigm used by Casey and co-authors22. We adopted a more reliable and balanced SC measure, as recommended by Duckworth and Kern12, by using factor analysis to extract a common SC factor (Factor S) from established self-report scales. SC was not related to EFs task performance (accuracy or reaction time), confirming some of the previous results8,10. Significant activation associated with inhibition was observed in bilateral frontal and parietal regions across participants, in line with prior research. We investigated both the correlations and the differences between the three SC groups (terciles) using whole-brain and ROI analyses, guided by previous literature. This approach offers new insights into the neural basis of SC, particularly in emotional contexts. Despite the lack of task performance differences, neural activity patterns during inhibition varied by SC level, suggesting distinct engagement with the task at the neural level.

The results of this study partially supported our hypotheses and revealed important distinctions in how individuals with varying levels of SC engage neural systems during response inhibition, in emotionally charged contexts. While strong SC did not consistently translate into better performance on EFs tasks, consistent with our first hypothesis, individuals with high SC showed increased engagement of the right IFG (RIFG) and left IFG (LIFG) when inhibiting responses to fearful faces. Casey et al.22 linked RIFG activation to successful inhibition across emotional conditions, whereas our findings suggest this engagement in high SC individuals is specific to fearful stimuli, suggesting a more context-sensitive recruitment of control-related regions. As predicted, areas of the prefrontal cortex previously linked to successful SC, such as the LIFG20, were more active during cognitive inhibition among those high on the SC dimension, but only when the inhibition targets were fearful faces. Unexpectedly, activity in the cerebellar vermis emerged as a distinguishing feature between individuals with strong SC and those with medium SC during the inhibition of social cues associated with fear. Partially in line with our second hypothesis and prior research, we found increased AI activation during inhibition, especially amongst medium SC individuals, in the positive stimuli condition. High SC individuals showed increased activity in the AI area (adjacent to IFG) only in the fearful cues condition. Contrary to our third hypothesis, we found no evidence that the reward system activity interferes with the inhibition of positive social cues in low SC individuals. Despite prior suggestions, we did not observe increased activity in the ventral striatum among low SC individuals when processing emotionally positive content22. Moreover, no significant increase in activation in either control-related or reward-related regions was observed in any of the conditions, indicating a possible disengagement from both control-related and conflict-monitoring systems. These findings support our proposed adaptive control modulation model, which posits that trait SC may influence the dynamic engagement of EFs, in line with context. The observed differences in neural activation, particularly in bilateral IFG and AI regions, despite similar behavioral performance, may suggest that individuals with high SC proactively recruit control-related neural systems in response to fearful facial expressions.

Although the main analyses did not reveal a significant overall group effect, planned comparisons between the groups showed that individuals with high SC exhibited greater activity during the inhibition of fearful faces compared to the medium SC group. Specifically, the difference was observed in RIFG (pars opercularis) and adjacent anterior insula (AI), as well as in the cerebellar vermis, at WB level. ROI analyses, guided by prior literature, further refined these findings, revealing stronger activation in the inhibition-related region (RIFG) and SC-relevant area (LIFG) in the high SC group relative to both medium and low SC individuals. Interestingly, the strong SC group did not show elevated activity in any region during the inhibition of positive social stimuli. Fear and happiness represent qualitatively different emotional states with unique social and cognitive implications. Fearful faces are typically associated with threat detection and heightened vigilance, which may demand not only different27 but possibly greater cognitive resources and inhibitory control during the regulation of negative emotional stimuli. High SC individuals may be more alert at managing the heightened arousal and attentional demands elicited by fear-related cues. Their activation patterns, particularly increased bilateral IFG arousal, suggest a goal-directed, anticipatory approach to regulation, where control mechanisms are activated during the planning phase. The left IFG, though less commonly linked to inhibition, has been associated with behavioral SC, particularly in individuals who effectively regulate food choices20. This study shows that it is also more active during the inhibition of negative social stimuli, among strong SC individuals, as measured via self-report methods. This contributes to why high SC participants demonstrate greater success in neural regulation of arousal associated with negative stimuli26. Interestingly, the cerebellar vermis also differentiated strong from medium SC individuals, suggesting its potential role in emotional and cognitive control. High SC individuals appear more attuned to threat-related cues; however, they do not show elevated activation when inhibiting responses to positive stimuli, such as happy faces. This may reflect lower approach tendencies, reduced perceived conflict, more efficient detection and resolution of task-tendency conflict, or less regulatory effort required.

In contrast, whilst WB analyses did not reveal significant group differences in the inhibition of positive social cues, we have identified a localized ROI finding. The medium SC group showed increased activation in the AI in comparison to high SC individuals. AI is linked to detecting conflict and task-relevant cues, often involved in inhibitory processes28,29. Surprisingly, the low SC group did not differ significantly from the medium and strong SC groups. Unlike high SC individuals, who may regulate such cues more efficiently, or low SC individuals, who may not engage regulatory mechanisms as strongly, medium SC participants may have an increased awareness of the need to suppress a socially reinforced response or require more effortful processing to detect and resolve conflict triggered by positive stimuli. These findings underscore the importance of considering SC as a spectrum rather than a binary trait, and suggest that medium SC individuals may rely more heavily on salience and conflict-monitoring systems when inhibiting emotionally positive cues. It also demonstrates how ROI analyses can detect localized effects missed by WB methods due to broader spatial scope and conservative thresholds.

There were no regions where low SC individuals showed greater activation compared to medium or high SC individuals in either emotional condition. Contrary to findings by Casey et al.22, we did not observe increased reward system activity during inhibition. However, some tendencies noted in the Supplementary Material may guide future research on this aspect. The absence of increased activation suggests that low SC may be linked to reduced engagement of control and conflict-monitoring systems during emotional processing. This could reflect a more passive or undifferentiated response to emotional stimuli, insufficient task demands to elicit stronger neural engagement, reduced sensitivity to socially rewarding or threatening cues, or weaker preparatory mechanisms for inhibition. Low SC may not simply be a matter of reactive overactivation, but may involve a broader disengagement from regulatory processes, even in emotionally or motivationally charged contexts.

These findings only partially align with previous research by Casey et al.22, who demonstrated that individuals with lower SC struggle more with suppressing responses to emotionally salient cues like happy faces. Our results extend this by showing that medium SC individuals may exhibit heightened sensitivity to such cues, requiring conflict-related regulation. Furthermore, our findings correspond with previous studies, emphasizing the role of preparatory activity in regions such as the AI and IFG in supporting proactive control23,28. The increased activation in high SC individuals to fearful faces may reflect such anticipatory engagement, while the lack of activation in low SC individuals may indicate reduced preparatory control and a more reactive processing style. It seems that accuracy or reaction time alone may not fully capture the complexity of EFs processes and their potential relationship with SC. The emotional nature of stimuli, particularly fear and happiness, appears to influence these patterns. The differential neural responses to emotional facial expressions observed across SC groups may reflect underlying differences in emotion regulation strategies and motivational salience. This should be approached with caution, as potential ceiling effects in task performance may have limited the sensitivity of the task to detect nuanced associations.

This study is limited by its use of only two emotional expressions. Including a broader range of emotional and threat-related stimuli could enhance understanding of the inhibited object’s informative value and context recognition in SC. For consistency and technical reasons, the study included only right-handed participants who met MRI criteria. Typical fMRI study limitations, such as correlation-based conclusions, lack of causal observations, low spatial precision, and other influencing variables (e.g., MRI discomfort, laboratory context) also apply to this research. Participants were selected both randomly and deliberately based on known SC levels to ensure a representative sample. Some effects emerged only when the analysis was narrowed down to the ROI highlighted in previous studies, suggesting that simple tasks may not reveal subtle behavioral or neural differences. Ceiling effects may have also reduced the task sensitivity. The findings may potentially reflect emotional reactivity, threat sensitivity, or task-related anxiety rather than EFs or SC alone. A more demanding task could help clarify these associations. Increasing task difficulty in future research could reveal more differences at the WB level and uncover additional mechanisms distinguishing effective self-controllers. We focused our analyses on the first unrotated factor of SC due to its theoretical and statistical relevance, though future work should explore other factors.

Understanding why individuals with a strong level of SC as a trait may be more assertive in potentially dangerous social situations, while others are not, is crucial for clinical aspects and therefore future research. We recommend recruiting participants with varying levels of SC from different social groups, and using more challenging cognitive tasks to limit the ceiling effect. This approach will help thoroughly explore the relationship between SC and cognitive control, uncovering potential other neural patterns. The study could also include more complex social cues like short videos or GIFs. Future research should investigate whether differences are related to negative facial expressions, negative emotional contexts, or specific to fear or danger-related information. Although current findings do not support previous evidence of reward system involvement in low SC individuals, revisiting this is important due to its clinical implications.

To conclude, our study suggests that a high level of SC allows for a more targeted allocation of energy during inhibition, focused on the goal when it appears important. These individuals appear to prioritize inhibition-related brain activity when the stimulus is perceived as socially or emotionally significant. In contrast, medium SC individuals invest more effort in regulating responses to positive cues, while low SC individuals show reduced neural engagement overall. For clinical practice, enhancing the ability to recognize potential social danger and emotional cues, alongside developing anticipation, planning, and outcome expectation skills, seems important for effective SC.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-five adult volunteers (37 women and 18 men), aged 20 to 66 years (Mage= 34.29, SD = 9.60), participated in the study. All were native Polish language speakers. 76% of the participants had higher education, 20% had secondary education, and 4% had vocational education. To ensure adequate representation of people with different levels of SC, the participants were recruited in a partly deliberate manner, based on their scores on the SC scale (Nowy Arkusz Samowiedzy, NAS-50, Nęcka et al., 2016). One participant was excluded due to an incomplete procedure, leaving 54 for analysis. See the Supplementary Material for a detailed description of the sample and recruitment procedure.

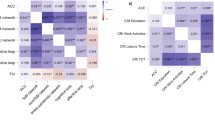

Questionnaires

SC was assessed using three Polish-language paper-and-pencil questionnaires:

-

1)

The NAS-50 Self-Control Scale (Nowy Arkusz Samowiedzy)16 that consists of 50 items measuring five factors on a five-point scale: Inhibition and Adjournment (IA), Switching and Flexibility (SF), Goal Maintenance (GM), Initiative and Persistence (IP), and Proactive Control (PC). The questionnaire is reliable (Cronbach α =.861) and valid (subscales α between.73 and.87). Its overall score correlates with Conscientiousness (NEO-FFI, r =.54, p <.001). High scores indicate high SC. Reliability level in this study was Cronbach α =.903 (N = 55).

-

2)

The Achievement Motivation Inventory (LMI) adapted to Polish31, which includes 170 items across 17 subscales, rated on a seven-point scale. It demonstrates good reliability (Cronbach α =.97, subscales α =.69-.85). Subscales include Flexibility, Courage, Preference for difficult tasks, Independence, Belief in success, Dominance, Eagerness to learn, Goal orientation, Compensatory effort, Caring for prestige, Pride in productivity, Commitment, Competitive spirit, Task focus, Assimilability, Perseverance, and Self-control. The last three subscales form one of the main factors of motivation for achievements - self-control. These items were included in the factor analysis of this study (α =.69-.77).

-

3)

The NEO-FFI personality inventory adapted to Polish32,33 includes 60 items measuring five personality factors: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness (subscale α =.68 to.82). Answers are given on a five-point scale. Conscientiousness (α =.82) reflects perseverance, motivation for goal-oriented actions, and organizational level. This subscale scores were used for factor analysis.

Additionally, two other questionnaires were used: the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI) to assess handedness and control for hemispheric dominance34, and the FCZ-KT35, although the results from the latter were not analyzed in this study.

Cognitive task

A hot Go/No Go task (GNG) was used to measure inhibition and working memory efficiency. It was presented using PsychoPy v3.0.7, based on parameters provided by Casey et al. (2011). The stimuli were black and white images of happy and fearful faces from the NimStim set36. The task was to press the button when the face specified by the instruction appeared (e.g., "React only to happy faces"). The task had four sessions with 48 trials each: 35 required a reaction - Go (73%) and 13 in which participants had to refrain from reacting - No Go (27%). Altogether, 70 Go and 26 No Go trials per stimulus type. Happy faces were the target in the first and third sessions, and fearful faces in the second and fourth. Stimuli were shown for 500 ms, followed by a fixation point "+" for 2–14.5.5 s (M ISI = 5.2 s), with longer ISI (8.8–14.5.8.5 s) every 30–45 s to allow the hemodynamic response to return to baseline. Two versions of the stimulus list and ISI in random order were used alternately for participants.

Neural activity registration

Neural activity was measured using a GE Discovery MR 750 3.0T scanner with a 16-channel head coil. Structural T1 sequence scans had a resolution of 256 x 256 voxels, a 240 mm field of view (FOV), and 136 × 1 mm layers. Anatomical images were acquired between the two tasks performed in the scanner. Functional scans (T2 EPI sequence) had the following parameters: TR = 2500 ms, TE = 30 ms, FA = 90°, 34 layers (4 mm thick) with a 240 mm FOV, no gaps between layers, and 64 x 64 voxel resolution. Images were acquired alternately, even then odd layers.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Commission for Research Ethics at the Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University (EC/05/092019) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. It was conducted in a private MRI laboratory in Krakow, Poland. Participants were informed about the procedure, duration, and contraindications. All participants were also informed about the anonymity and confidentiality of the individual results, and how the results would be used, and data processing. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study in writing, as well as consent to data processing. They received a CD with a recording of their brain’s anatomical image after completing the study, but no financial compensation. Participants abstained from alcohol for a day and smoking for three hours, and followed standard MRI procedures.

After registration, participants completed four questionnaires (NAS-50, LMI, NEO-FFI, and FCZ-KT) and the handedness questionnaire (EHI), taking about 30–60 minutes. They familiarized themselves with the computer tasks by performing two sample sessions outside the scanner (about 5 minutes). In the scanner, participants performed two tasks - a Flanker task (not considered here) and a GNG task - each preceded by detailed instructions and two 2-minute training sessions. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and as accurately as possible, and to avoid body movement during the scans. The instruction was displayed at the beginning of each session and remained consistent throughout that session (e.g., “react only to happy faces”). The first 20-minute task was followed by a 5-minute rest for anatomical imaging. Then, participants completed the GNG task, which took about 20 minutes.

Data analysis

Raw questionnaire data were manually transferred to a digital format, missing values were imputed with midpoints, and reversed items were recoded. Exploratory factor analysis on NAS-50 items, LMI Self-Control factor items, and NEO-FFI Conscientiousness items was conducted to extract a latent variable of SC. The first non-rotated factor items were used for further analysis and named the general SC factor, in short, Factor S. Participants were grouped into low, medium, and high SC terciles Factor S scores were weakly positively correlated with age (Pearson’s r =.33, p <.05, N = 55). Disproportionate male-to-female ratio limits the interpretability of any gender-related comparisons. A detailed description of the factor analysis is in the Supplementary Material.

Task performance measures included accuracy (correct, incorrect, and omissions) and response time for correct Go trials. Accuracy was summarized as a percentage of correct trials. To check the relationship between task performance (reaction time and accuracy) and SC (Factor S), we used Pearson’s correlation and the Kruskal-Wallis H test for between-group comparisons. All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics (v25).

Neural activity was analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM 12) on MATLAB R18a. Standard preprocessing included slice-timing, realignment (head movement correction), co-registration (alignment to individual high-resolution brain images), normalization (to the ICBM spatial pattern for European brains), and smoothing with a 6-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

First-level analysis was based on a general linear model. To check the reaction of the individual subjects, two models were created: the first included responses to Go stimuli, No Go stimuli, errors, and six head movement regressors; the second included reactions to happy faces (Go happy), fearful faces (Go fearful), errors, and six head movement regressors. The regressors were multiplied by the canonical function of the hemodynamic response.

Individual contrast images were calculated and used in group random-effect analysis. For the main effect of the GNG task (manipulation check), contrasts No Go minus Go and its inverse were created to test inhibition effects and the first hypothesis. To examine this effect in relation to the type of emotions depicted, two contrasts were created, in the second model: No Go fearful minus Go fearful and No Go happy minus Go happy. Only correct trials were considered (correct responses and correct lack of responses). Results were reported with p <=.05 with Family Wise Error correction for multiple comparisons (FWE).

To examine the relationship between neural activity and Factor S, three different signal analyses were conducted. As linear models alone could miss meaningful differences and given our a priori hypotheses regarding specific group differences, we conducted planned between-group comparisons to directly test for these expected patterns.

-

1)

To explore the relationship between SC and brain activity, individual Factor S values were used as a model covariant in the No Go minus Go contrast (search threshold: p ≤.001 uncorr., k = 1).

-

2)

To check task effects between different SC level groups, three univariate analyses of variance with planned comparisons of low, medium, and high Factor S groups were used for all types of stimuli: No Go minus Go (1), for fearful: No Go fearful minus Go fearful (2), and for happy: No Go happy minus Go happy (3).

-

3)

A confirmatory analysis using a priori defined regions of interest (ROIs, 10 mm spheres) compared the results to other findings. ROIs included the right IFG (x = 35, y = 11, z = −4) and ventral striatum (x = 13, y = 26, z = 10) based on Casey et al.22, left IFG (x = −45, y = 42, z = 12) based on Hare et al.20, and left anterior insula (x = −36, y = 20, z = −8) based on Berkman et al.29. ROIs were defined based on independently reported peak coordinates from prior studies, to avoid circularity and enhance the interpretability and generalizability of ROI-based analyses.

We reported results significant at the cluster level at p ≤.05 FWE whole brain and at p ≤.05 FWE with small volume correction (SVC) in the case of ROI analysis. We used a standard SPM MNI brain template and the MRIcroGL program to illustrate the results.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Duckworth, A. & Seligman, M. Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 16(12), 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x (2005).

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F. & Boone, A. L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Pers. 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x (2004).

Mischel, W. The marshmallow test: mastering self-control. little, brown and co. (2014)

Bridgett, D. J., Oddi, K. B., Laake, L. M., Murdock, K. M. & Bachmann, M. N. Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion 13, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029536 (2013).

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y. & Rodriguez, M. I. Delay of gratification in children. Sci. New Series 244(4907), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2658056 (1989).

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Caspi, A. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. PNAS-50 Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 (7) 2693–2698 https://doi.org/10.1073/pNAS-50.1010076108 (2011)

Wiese, C. W. et al. Too much of a good thing? Exploring the inverted-U relationship between self-control and happiness. J. Pers. 86(3), 380–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12322 (2017).

Nęcka, E., Gruszka, A., Orzechowski, J., Nowak, M. & Wójcik, N. The (in)significance of executive functions for the trait of self-control: A psychometric study. Front. Psychol. 9, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01139 (2018).

Miyake, A. & Friedman, N. P. The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: four general conclusions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 21(1), 8–14 (2012).

Scherbaum, S., Frisch, S., Holfert, A.-M., O’Hora, D. & Dshemuchadse, M. No evidence for common processes of cognitive control and self-control. Acta Psychologica 182, 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2017.11.018 (2018).

Miyake, A. et al. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Psychol. Rev. 111(1), 49–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.49 (2000).

Duckworth, A. L. & Kern, M. L. A meta-analysis of the convergent validity of self-control measures. J. Res. Pers. 45(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.02.004 (2011).

Gillebaart, M. The ‘operational’ definition of self-control. Front. Psychol. 9, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01231 (2018).

Duckworth, A. L. & Gross, J. J. Self-control and grit: related but separable determinants of success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 319–325 (2014).

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D. & Tice, D. M. The strength model of self-control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16, 351–355 (2007).

Nęcka, E. et al. NAS-50 and NAS-40: New scales for the assessment of self-control. Polish Psychol. Bullet. 47(3), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1515/ppb-2016-0041 (2016).

Fujita, K. On conceptualizing self-control as more than the effortful inhibition of impulses. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 15(4), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411165 (2011).

Duckworth, A. L., Milkman, K. L. & Laibson, D. Beyond willpower: strategies for reducing failures of self-control. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest: J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 19(3), 102–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618821893 (2018).

Vink, M. et al. Towards an integrated account of the development of self-regulation from a neurocognitive perspective: A framework for current and future longitudinal multi-modal investigations. Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. 45(100829), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100829 (2020).

Hare, T. A., Camerer, C. F. & Rangel, A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science 324(646), 646–648. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1168450 (2009).

Waegeman, A., Declerck, M., Boone, C., Van Hecke, W. & Parize, E. Individual differences in self-control modulate the neural underpinnings of executive control. Neuropsychology 28(6), 910–920. https://doi.org/10.1037/npe0000018 (2014).

Casey, B. J., Somerville, L. H., Gotlib, I. H., Ayduk, O., Franklin N. T., Askren M. K., Shoda, Y. Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later. Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences, 108 (36) 14998-15003. https://doi.org/10.1073/pNAS-50.1108561108 (2011)

Braver, T. S. The variable nature of cognitive control: a dual mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 106–113 (2012).

Gross, J. J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev. General Psychol. 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271 (1998).

Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M. & Grunedal, S. Facial reactions to emotional stimuli: automatically controlled emotional responses. Cognit. Emot. 16, 449–472 (2002).

Paschke, L. M. et al. Individual differences in self-reported self-control predict successful emotion regulation. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 11(8), 1193–1204. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw036 (2016).

Etkin, A., Büchel, C. & Gross, J. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn4044 (2015).

Kaboodvand, N., Karimi, H., & Iravani, B. (2024). Preparatory activity of anterior insula predicts conflict errors: integrating convolutional neural networks and neural mass models. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 67034. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67034-5(2024)

Berkman, E. T., Falk, E. B. & Lieberman, M. D. Interactive effects of three core goal pursuit processes on brain control systems: goal maintenance, performance monitoring, and response inhibition. PloS ONE 7(6), e40334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040334 (2012).

Swick, D., Ashley, V. & Turken, U. Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response inhibition. BMC Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-9-102 (2008).

Klinkosz, W., & Sękowski, A. E. H. Schulera i M. Prochaski polska wersja Inwentarza Motywacji Osiągnięć – Leistungsmotivationsinventar (LMI) [The Polish version of the Achievement Motivation Inventory – Leistungsmotivationsinventar (LMI)] Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 12 (2) 253–264 (2006)

Zawadzki, B., Strelau, J., Szczepaniak, P. & Śliwińska, M. Inwentarz Osobowości NEO -FFI Costy i McCrae. Adaptacja polska. Podręcznik [NEO-FFI Personality Inventory by Costa and McCrae. Polish Adaptation. Manual]. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP. (1998)

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. Neo PI-R professional manual. psychological assessment resources (Psychological Assessment Resources Inc, 1992).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 (1971).

Zawadzki, B. & Strelau, J., FCZ-KT Formalna Charakterystyka Zachowania - Kwestionariusz Temperamentu [FCZ-KT Formal Characteristics of Behavior - Temperament Questionnaire]. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP. (1997)

Tottenham, N. et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatr. Res. 168(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The project was financed by the National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) in Poland on the basis of decision number DEC-2013/08/A/HS6/00045.

Funding

The project was financed by the National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) in Poland on the basis of decision number DEC-2013/08/A/HS6/00045.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K-G.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing T.S.L.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing E.N.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Commission for Research Ethics at the Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University (EC/05/092019) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korona-Golec, K., Ligeza, T.S. & Nęcka, E. Overlapping neural activations between trait self-control and cognitive inhibition during emotional stimuli processing. Sci Rep 15, 40814 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24638-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24638-9