Abstract

We report for the first time the synthesis of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) derived from Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba) leaves using a hydrothermal method at 180 °C for 10 h for ultrasensitive detection of Fe3+ ions in aqueous solutions. The obtained CQDs have an average size of 3.5 nm and exhibit stable blue fluorescence, making them suitable for optical sensing applications. They show remarkable selectivity toward Fe3+ ions and achieve an ultralow detection limit of 0.018 µM, outperforming most reported CQD-based sensors. The fluorescence quenching behavior follows the Stern–Volmer relation and confirms a static quenching mechanism between Fe3+ ions and surface functional groups of the CQDs. These results highlight the potential of jojoba-derived CQDs as low-cost, sustainable, and highly effective fluorescent probes for Fe3+ ion detection, offering a promising route for environmental monitoring applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past two decades, extensive research has focused on fabricating Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) from natural, green, and renewable carbon precursors as an alternative to traditional organic dyes and semiconductor quantum dots1,2,3. These CQDs, a novel type of carbon-based nanomaterial, have shown considerable promise due to their unique optical, electronic, and chemical properties4. Researchers have defined them as carbon-based nanomaterials with sizes below 10 nm. CQDs were first discovered by Xu in 2004 during the purification of single-walled carbon nanotubes5, with their existence later confirmed by Sun in 20066. Since their discovery, various techniques have been extensively reported for producing fluorescent CQDs, including hydrothermal synthesis, chemical oxidation, arc discharge, laser ablation, and microwave-assisted methods, among others7. Currently, the hydrothermal approach is the most widely adopted due to its cost-effectiveness, non-toxicity, environmental friendliness, and precise control over CQD properties. This method has been widely employed to synthesize CQDs from various natural precursors such as orange juice8, watermelon peels9, and banana peels10. These biomass-derived sources offer several advantages over traditional quantum dot precursors, including natural abundance, low cost, non-toxicity, and environmental friendliness, making them attractive green alternatives for sustainable CQD synthesis11.

CQDs are appealing for a wide range of applications owing to several intriguing properties12. Their powerful and adjustable photoluminescence, which allows them to emit varying colors of light based on surface chemistry and size, is one of their most remarkable characteristics6. Consequently, they are attractive candidates for many applications such as, light-emitting diodes13, supercapacitors14, solar cells, bioimaging, cell imaging15, and especially as fluorescence-based sensors of a wide range of analytes. For instance, CQDs have been employed in the detection of amino acids, food additives, and pharmaceutical residues due to their high sensitivity, low toxicity, and tunable photoluminescence properties16,17.

Interestingly, CQDs synthesized from various plant sources such as Borassus flabellifer18, Mangifera indica leaves19, betel leaf (Piper betel)20, and zedoary (Curcuma zedoaria)21 have demonstrated effective detection of metal ions, particularly Fe3+ ions22. While Fe3+ is an essential trace element for both humans and aquatic organisms, its excessive presence in the environment can cause severe ecological imbalance and significant health risks23. Therefore, the development of reliable strategies for monitoring Fe3+ is of critical importance. Notably, plant-derived CQDs typically exhibit a high degree of surface functionalization, enriched with diverse groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amino functionalities24. These groups play a crucial role in dictating the surface chemistry of CQDs, where oxygen- and nitrogen-containing moieties facilitate strong coordination with metal ions and promote electron transfer from photoexcited CQDs to Fe3+, resulting in efficient fluorescence quenching25.

Jojoba (Simmondsia Chinensis) plant of the Simmondsiaceae family, is a perennial shrub plant that is indigenous to the arid regions of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. Jojoba has thick, leathery leaves and is a dioecious plant, meaning it has male and female flowers on separate plants26. Female plants produce fruit with one seed that looks somewhat like an acorn, known as a nut27. The Jojoba plant has become an essential plant around the world due to its medicinal properties, which have made it to be cultivated in many countries, including Chile, Argentina, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt28. It is highly prized for its seeds, which yield a special oil known as “liquid wax”. It’s referred to as liquid wax rather than oil because it contains mainly fatty acid ethers, sterols, and vitamins, with only small amounts of triglyceride esters29, giving the jojoba plant various potential applications in cosmetics, antifungal and anti-microbial, dermatology, and skin care activities30. However, this work highlights the potential of utilizing jojoba leaves for the sustainable synthesis of carbon quantum dots, which may open new avenues for their eco-friendly production. The primary objective of using jojoba leaves is to address their status as a discarded waste product with a lack of potential applications, thereby reducing organic waste accumulation in the environment. To this end, we report the first green synthesis of fluorescent CQDs derived from jojoba leaves and their application as an optical sensor for the ultrasensitive detection of Fe3+ ions in aqueous solution.

Experimental details

Materials

Jojoba leaves were collected from a local farm in Egypt (Wadi Natrun Farm, Egypt). The salts of different metal ions, which include Co(NO3)2.6H2O, CuSO4.5H2O, MgSO4.7H2O, CaCl2, FeCl3, (Ni(NO3)2.6H2O), MnCl2.6H2O, and ZnCl2, from Fisher Scientific UK, Deionized water was used throughout the experiment.

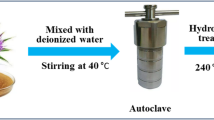

Synthesis method

The experimental preparation was described as shown in schematic Fig. 1. The jojoba leaves were washed thoroughly using tap and deionized water to remove any dust particles and other impurities. Clean leaves were subsequently scratched and soaked in 100 mL of deionized water as a solvent for extraction within two days at room temperature. The extract was filtered with standard double-ring filter paper, then 30 mL of the extracted sample was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated in an oven at 180 °C for 10 h. The reaction was left to cool to room temperature and filtered again using both double rings filter paper followed by a syringe filter (0.22 µm). A light brown aqueous solution was obtained, and the carbon dots were collected using 1000 Da dialysis membrane against DI water for 48 h to get purified CQDs which are free from low-molecular-weight impurities and fluorophores that could otherwise interfere with their optical properties or sensing performance. The resultant supernatant was stored at 4 °C, which later lyophilized for further characterization.

Characterization instruments

A transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM-2100F from JEOL Company, Japan, operated at 200 kV) was used to study the morphology of the formed CQDs. The samples for analysis were prepared on a copper grid coated with carbon and allowed to dry at room temperature. Bruker AVANCE HD III Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), operated at 400 MHz (1H NMR) and 100.40 MHz (13C NMR). The solvent used for compound 1 was DMSO. Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), VERTEX 70v from Bruker Company, was used to determine the surface functional group of the produced CQDs. FS5 Spectrofluorometer (Edinburgh Instrument) was used to analyze fluorescence intensity and fluorescence lifetimes of the synthesized CQDs. Hitachi U-3900 spectrophotometer was used to measure the UV–visible spectra of the synthesized CQDs. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was also used to investigate the chemical composition, elemental states, and electronic states of synthesized CQDs, and Malvern zeta sizer nano zeta potential was used to evaluate the stability and surface charge of synthesized CQDs.

Sensing of Fe3+ ions

To evaluate the metal ion selectivity of the synthesized CQDs, fluorescence intensity was monitored as a function of wavelength in the presence of various metal ions. In details, 50 µL of different metal ion solutions (4 µM), including Co(NO3)2·6H2O, CuSO4·5H2O, MgSO4·7H2O, CaCl2, FeCl3, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, and MnCl2·6H2O, were added to 2 mL of the as-prepared CQD solution. Among all tested metal ions, Fe3+ exhibited the most pronounced quenching effect, resulting in the lowest fluorescence intensity of the CQDs. To further investigate the sensitivity of CQDs towards Fe3+ ions, fluorescence measurements were performed using the same stock solution (4 µM). Incremental additions of 5 µL of the Fe3+ solution were made to 2 mL of CQDs, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded after each addition. The results clearly demonstrated a progressive decrease in fluorescence intensity with increasing Fe3+ ion concentration, confirming the strong quenching effect of Fe3+ on the CQDs.

Measurement of fluorescence quantum yield (QY)

The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of the synthesized CQDs was determined using an absolute method with an FS-5 Spectrofluorometer equipped with an SC-30 Integrating Sphere (Edinburgh Instruments). In this approach, the integrating sphere captures both the excitation light (transmitted and scattered) and the total emitted fluorescence. The QY is then calculated based on the ratio of the number of emitted photons to the number of absorbed photons, with the absorption derived from the difference between the incident and transmitted excitation light. Using this method, the QY of the CQDs was determined to be 3.35%.

Results and discussion

Morphological and structural properties of CQDs

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was employed to analyze the morphology of the CQDs derived from jojoba leaves, as presented in Fig. 2a,b. These images illustrate well dispersed, quasi-spherical nanoparticles, surrounded by an amorphous carbon matrix28. The particle size distribution histogram in Fig. 2c indicates an average diameter of 3.50 nm, calculated from 90 particles. Furthermore, Fig. 2(b; inset) reveals well-defined lattice fringes consistent with a graphitic structure, with an interplanar spacing of 0.22 nm, as highlighted in the inset, in agreement with previous findings31.

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to determine the surface functional groups of the as-prepared CQDs. The surface of Jojoba leaves synthesized CQDs indeed indicate various oxygenated groups, as indicated by the FTIR spectrum as seen in Fig. 2d. Namely, the FTIR spectrum reveals the presence of O–H stretching vibrations at 3296 cm−1 with broad high peak intensity, the weak absorption peak that occurs at 2932 cm−1 is assigned to C–H stretching vibration32. The peak observed at 1600 cm−1 is ascribed to carbon-to-oxygen double bond C=O , which may be related to the presence of minor impurities. The peak at 1397 cm−1 can be due to the presence of C–C, while the stretching vibrations peak at 1068 cm-1 is related to C–O–C functional groups of ether linkage33.

ESI–MS (Electrospray Ionization Mass spectroscopy) analysis of the synthesized CQDs in negative mode exhibited molecular ion peaks at m/z = 195 [M–1] and m/z = 239 [M + 2Na–1], corresponding to the molecular formula C7H16O6. In addition, NMR measurements provided detailed structural information. The 13C-NMR spectrum (Fig. 3) and 1H-NMR spectrum (Fig. 4), including both 1D and 2D experiments (HMQC, and HMBC), played a crucial role in structure elucidation. The 1H-NMR spectrum showed overlapping multiple peaks between δ 3.02–3.62, corresponding to the methylene protons (1–7). The 13C-NMR spectrum displayed seven negative peaks in the hydroxyl group region, indicating methylene carbons at δ 60.04 (C-1, C-7), δ 70.56 (C-3), δ 71.41 (C-4), δ 72.33 (C-6), δ 72.77 (C-2), and δ 73.06 (C-1), in addition to δ 84.15 (C-5). Some small-intensity peaks appeared in the 13C 1D and 2D spectra due to minor impurities. The HMBC and HMQB spectra (Fig. 5a,b) showed cross peaks between (H-5, C-5), (H-6, C-5), (H-7, C-5), (H-5, C-6), (H-4, C-6), and (H-1, C-2). Based on these combined results, the isolated compound of the synthesized CQDs (Fig. 6) was identified as 2-(2-((hydroxyethoxy)methoxy)ethyl)peroxy)ethan-1-ol.

The surface chemical composition and elemental states of the synthesized CQDs were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), of which multiple distinct peaks spectra were identified at 284.8 eV, 399.8 eV, and 532.9 eV, as shown by survey in Fig. 7a. It is found that the CQDs contain 61.41% of carbon, 4.80% of nitrogen, and 26.72% of oxygen respectively. The respective binding energies for carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen in the survey were deconvoluted as below. A study deconvolution of C1s shown in Fig. 7b indicates three peaks at 284.8 eV, 286.2 eV, and 288.6 eV that are assigned to carbon-to-carbon single bond (C–C), carbon to nitrogen, and carbon to oxygen single bond (C–N/C-O), and carbon to oxygen double bonds (C=O).

Figure 7c shows O1s deconvoluted to two peaks at 532.2 eV and 533.2 eV that can be attributed to C=O and C–O–C functional group, while the high-resolution XPS spectrum of N1s shown in Fig. 7d indicates two peaks at 399.9 eV, 401.8 eV, which correspond to pyrolytic N and pyridinic N that can help to enhance fluorescence quantum yield and can provide localized states within the bandgap which can also help in the facilitation of electron transitions that enhance fluorescence emissions34.

Based on these findings, the CQDs might have a nanocrystalline graphitic sp2 carbon nucleus functionalized by sp3 carbon defects and peripheral carboxyl/carbonyl groups. These studies collectively verify that CQDs have a high concentration of hydrophilic groups on their surface, which contributes to their exceptional water solubility.

Optical properties of CQDs

The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the synthesized CQDs were recorded at excitation wavelengths ranging from 290 to 420 nm in 10 nm steps, as shown in Fig. 8a. The emission intensity peaked at 415 nm under 320 nm excitation. A clear excitation-dependent behavior was observed: as the excitation wavelength increased, the emission peak gradually shifted toward longer wavelengths (red shift), while the overall PL intensity decreased at excitations above 330 nm. This behavior is typical of CQDs and is generally linked to the presence of various surface states and size distributions, which create multiple emissive sites. The UV–vis absorption spectrum of the synthesized CQDs was measured across the range of 200–800 nm. Two characteristic peaks appeared at 260 nm and 360 nm, as shown in Fig. 8b. The peak at approximately 260 nm corresponds to the π → π* electronic transition of the conjugated sp2 C=C bonds, while the peak at around 360 nm results from the n → π* transitions of C=O groups. The inset images in Fig. 8b(i,ii) display the appearance of the CQDs under daylight and UV illumination at 365 nm, confirming their strong fluorescence capabilities.

The synthesized CQDs showed excellent fluorescence stability under different environmental conditions. As shown in Fig. 9a, their fluorescence intensity stayed stable over time, which is important for reliable fluorescence-based sensing applications. Additionally, the CQDs remained highly stable in saline environments, as seen in Fig. 9b, where there were negligible changes in fluorescence across NaCl concentrations from 0 to 500 mM. Moreover, the CQDs demonstrated good stability over a wide pH range (4–11), as illustrated in Fig. 9c.

The QY of the synthesized CQDs was determined using an absolute quantum yield measurement system (Fig. 10), yielding a value of 3.35%. Although relatively modest compared to chemically engineered CQDs, this value is consistent with many plant-derived CQDs and highlights the effectiveness of jojoba leaves as a sustainable precursor.

Figure 11 shows the Zeta potential spectrum for the synthesized CQDs with a potential value of − 22.0 mV, indicating moderate electrostatic repulsion between particles. This value demonstrates that CQDs remain stable enough for sensing applications within the timescales tested in this study35.

Optical properties of CQDs

The fluorescence selectivity of the synthesized CQDs toward various metal ions (Ca2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Ni2+, and Zn2+) was evaluated by monitoring their effect on the fluorescence intensity. For each test, 50 µL of a 4 µM metal ion solution was added to 2 mL of CQDs. The initial fluorescence intensity of the CQDs without metal ions was denoted as \({F}_{0}\), while f represents the intensity after ion addition, with excitation at 320 nm. Among the tested ions, Fe3+ caused a pronounced quenching of the CQD fluorescence, whereas the other ions produced negligible effects, as illustrated in Fig. 12a. Moreover, a quantitative selectivity test was performed to further evaluate the preferential interaction of CQDs with Fe3+ ions in the presence of competing metal ions. As shown in Fig. 12b, the fluorescence intensity of the CQDs in mixed-ion solutions remained strongly quenched only in the presence of Fe3+, while the influence of other metal ions was negligible. This result confirms that the CQDs exhibit a strong affinity and high selectivity toward Fe3+ even under competitive conditions.

To investigate the sensitivity and linearity range of our CQDs towards the analyte, we prepared different concentrations of Fe3+ ion using the same concentration (4 µM), and a similar technique by adding 5 µL to 2 mL of CQDs, and each time, fluorescence intensity is checked. It’s noticed that the fluorescence intensity of the CQDs decreases as the concentrations of Fe3+ ions increase in the sample, as shown in Fig. 12c, following a linear relationship expressed by \(y=3.07x+0.99\). Then, this relationship between the Fe3+ ion concentrations and the fluorescence intensity ratio \({F}_{0}/F\) at the range of 0.016–0.37 µM with R2 = 0.985 was found, as shown in Fig. 12d, and according to the Stern–Volmer equation \({F}_{0}/F\)= \(1+{K}_{sv}[Q]\), where \(F\) and \({F}_{0}\) are the fluorescence intensities of the CQDs with and without Fe3+, respectively, \({K}_{sv}\) is the quenching constant, while Q is the Fe3+ concentration.

The limit of detection (LOD) = 3σ/s, where s is the linear fit slope and σ is the standard deviation, was found to be 0.018 µM. This value is the smallest obtained so far for Fe3+ ion detection using biomass-derived nanomaterials and demonstrates that our CQDs represent one of the most sensitive fluorescence-based detection methods for Fe3+ compared to other reports in the literature (see Table 1). It is worth noting, however, that biomass-derived CQDs in general also demonstrate relatively high limits of detection in some cases, highlighting the significance of achieving such an ultra-low value in this work.

Real sample analysis

To assess practical applicability and the feasibility of the synthesized CQD-based sensor as a probe for Fe3+ detection, a sample of tap water, collected from the Energy Materials Lab, Egypt-Japan University of Science and Technology (E-JUST), Egypt. The water sample underwent filtration through a 0.22 mm membrane to eliminate any potential interfering substances that may interact with the CQDs. Following the same procedure by adding (20, 40, 60, and 80) µL of prepared concentration (4 µM) of Fe3+ ion into 2 mL of CQDs and 1 mL of tap water, the added concentrations of Fe3+ were calculated using the dilution equation and their corresponding found concentrations from the calibration curve, (see Table 2). The recovery rates are within the range of (80.1–114.0) %, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) for the triplicate measurements falls below 5%. These findings suggest that this sensor method is effective for the detection of Fe3+ in tap water.

Mechanism of CQDs fluorescence quenching by Fe3+

Fluorescence quenching of CQDs by Fe3+ primarily arises from strong interactions between Fe3+ ions and oxygen- or nitrogen-containing surface groups on the CQDs, such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and particularly phenolic –OH functionalities. These groups can chelate Fe3+ through inner-sphere coordination, providing multiple oxygen donor sites and a polar environment that favor complexation. The predominance of oxygen donor sites on the CQD surface accounts for the high selectivity toward Fe3+ (Fig. 12b). As a result, stable non-emissive CQD–Fe3+ complexes are formed, leading to fluorescence quenching via a static mechanism. In this case, the population of emissive species decreases while the excited-state lifetime of the remaining fluorophores remains unchanged, as illustrated in Fig. 13a.

One the other hand, dynamical quenching which involve the interaction between the excited state CQDs and the ferric ions resulting in fluorescence quenching. Figure 13b shows that Fe3+ has significant potential to quench the FL by energy or electron transfer from an excited state to its 3d orbital owing to its paramagnetic behavior39,40. In particular, the oxygenated groups on the CQDs can donate lone pairs to the 3d orbitals of Fe3+, facilitating complexation and electron transfer37. Upon excitation of the CQDs, electron–hole (e−/h+) pairs are generated. The excited electrons can then transfer to the Fe3+ 3d orbitals, suppressing radiative recombination and thereby quenching fluorescence, as shown in Fig. 13b.

To probe this quenching mechanism in greater detail, time-resolved photoluminescence (PL) measurements were carried out in the absence and presence of Fe3+ ions. Samples have excited using 340 nm picosecond pulsed LED, and the fluorescence decay profiles have been fitted according to Eq. (1)

where τ1, τ2, and τ3 represent distinct decay components; A is the baseline value; and B1, B2, and B3 are the corresponding amplitudes. The PL decay curves are presented on Fig. 14.

The calculated lifetimes, along with the average lifetime \(\left( {\tau_{avg} } \right)\), are summarized in Table 3 for different Fe3+ concentrations (30 and 60 µL). The average lifetime was calculated using Eq. (2)41

The results show that \({\tau }_{avg}\) remains almost unchanged with increasing Fe3+ concentration, confirming that the interaction follows a static quenching mechanism42. In this case, Fe3+ ions form stable ground-state complexes with CQD surface groups, particularly through direct interactions with phenolic hydroxyl groups on the CQD surface, rather than quenching fluorescence through collisional encounters. This strong binding underlies both the high selectivity and the ultrasensitive detection achieved, since competing ions are less likely to form such stable complexes38. However, static quenching may limit sensor reusability if the CQD–Fe3+ complexes are too stable. In contrast, dynamic quenching caused by collisional interactions typically shortens the excited-state lifetime, is reversible, but often less selective and highly dependent on environmental conditions such as temperature and solvent viscosity. Thus, identifying the quenching pathway provides valuable insights for designing and optimizing CQD-based sensors42,43.

Conclusion

We have successfully demonstrated a facile and environmentally friendly one-pot hydrothermal synthesis of CQDs from abundant jojoba leaves, underscoring both the sustainability of this approach and its potential scalability for cost-effective production. The resulting CQDs, with an average diameter of 3.5 nm, exhibited blue fluorescence with a quantum yield of 3.35%. These CQDs proved effective for Fe3+ ion detection, showing a significant fluorescence quenching response with an ultra-low detection limit of 0.018 µM. The quenching mechanism was confirmed to be static, as evidenced by the unchanged fluorescence lifetime decay of the quenched emission, highlighting their potential as ultrasensitive optical probes for Fe3+. This green synthesis strategy also opens avenues for exploring other plant-derived precursors in the development of CQDs, broadening their applicability in areas such as biomedical imaging and industrial monitoring.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Arumugham, T., Alagumuthu, M., Amimodu, R. G., Munusamy, S. & Iyer, S. K. A sustainable synthesis of green carbon quantum dot (CQD) from Catharanthus roseus (white flowering plant) leaves and investigation of its dual fluorescence responsive behavior in multi-ion detection and biological applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 23, e00138 (2020).

Qurtulen, et al. One-pot synthesized fluorescent CDs from Syzygium cumini for metal ion sensing and cell imaging. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 160, 111883 (2024).

Patra, S. et al. One-step green synthesis of in–situ functionalized carbon quantum dots from Tagetes patula flowers: Applications as a fluorescent probe for detecting Fe3+ ions and as an antifungal agent. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 442, 114779 (2023).

Lu, M., Duan, Y., Song, Y., Tan, J. & Zhou, L. Green preparation of versatile nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots from watermelon juice for cell imaging, detection of Fe3+ ions and cysteine, and optical thermometry. J. Mol. Liq. 269, 766–774 (2018).

Xu, X. et al. Electrophoretic analysis and purification of fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12736–12737 (2004).

Sun, Y. P. et al. Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 7756–7757 (2006).

El-Shafey, A. M. Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications. Green Process. Synth. 10, 134–156 (2021).

Gholipour, A. & Rahmani, S. The green synthesis of carbon quantum dots through one-step hydrothermal approach by orange juice for rapid, and accurate detection of dopamine. J. Fluoresc. 34, 2665–2677 (2024).

Zhou, J., Sheng, Z., Han, H., Zou, M. & Li, C. Facile synthesis of fluorescent carbon dots using watermelon peel as a carbon source. Mater. Lett. 66, 222–224 (2012).

Nasseri, M. A., Keshtkar, H., Kazemnejadi, M. & Allahresani, A. Sustainable synthesis of carbon quantum dots from banana peel waste using hydrothermal process for in vivo bioimaging. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–12 (2020).

Jose, J., Rangaswamy, M., Shamnamol, G. K. & Greeshma, K. P. A short review on natural precursors-plant-based fluorescent carbon dots for the targeted detection of metal ions. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 7, 100114 (2024).

Ling, C., Wang, Z., Li, C. & Wang, W. Eco-friendly and sustainable synthesis of carbon quantum dots from waste sulfuric acid of alkylation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 143, 447–454 (2025).

Hosh, D., Sarkar, K., Devi, P., Kim, K. H. & Kumar, P. Current and future perspectives of carbon and graphene quantum dots: From synthesis to strategy for building optoelectronic and energy devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 135, 110391 (2021).

Permatasari, F. A., Irham, M. A., Bisri, S. Z. & Iskandar, F. Carbon-based quantum dots for supercapacitors: Recent advances and future challenges. Nanomaterials 11, 1–34 (2021).

Mohamed, W. A. A. et al. Quantum dots synthetization and future prospect applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 10, 1926–1940 (2021).

Gholipour, A., Jahanshahi, M. & Emadi, H. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots and fe-doped carbon quantum dots as fluorescent probes via one-step microwave process for rapid and accurate detection of diclofenac sodium. J Clust Sci 35, 237–251 (2024).

Gholipour, A. & Rahmani, S. The synthesis of fluorescent carbon quantum dots for tartrazine detection in food: A novel one-step microwave heating approach. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 31(8), 743–751 (2023).

Nagaraj, M. et al. Detection of Fe3+ ions in aqueous environment using fluorescent carbon quantum dots synthesized from endosperm of Borassus flabellifer. Environ. Res. 212, 113273 (2022).

Singh, J. et al. Highly fluorescent carbon dots derived from Mangifera indica leaves for selective detection of metal ions, Science of The Total Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 720, 137604 (2020).

Nagaraj, M. et al. Detection of Fe3+ ions in aqueous environment using fluorescent carbon quantum dots synthesized from endosperm of Borassus flabellifer. Environ Res 212, 113273 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Green synthesis and multifunctional applications of nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots via one-step hydrothermal carbonization of Curcuma zedoaria. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 415, 1917–1931 (2023).

Shabbir, H., Csapó, E. & Wojnicki, M. Carbon quantum dots: The role of surface functional groups and proposed mechanisms for metal ion sensing. Inorganics (Basel) 11, (2023).

Phaenark, C. Phankamolsil, Y. & Sawangproh, W. Ecological and health implications of heavy metal bioaccumulation in Thai Fauna: A systematic review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety, 285, (2024).

Xie, J., Wu, Z., Sun, J., Lv, C. & Sun, Q. Green synthesis of carbon quantum dots derived from lycium barbarum for effective fluorescence detection of Cr (VI) sensing. J Fluoresc 34, 571–578 (2024).

Ozturk, M. & Hakeem, K. R. Plant and Human Health. Springer 1, (2018).

Alyousif, N. A., El Sherif, F., Yap, Y. K. & Khattab, S. Selection of salt-tolerant jojoba (Simmondisa chinensis L.) cultivars via in vitro culture. Horticulturae 9, 1–13 (2023).

Gad, H. A. et al. Jojoba oil: An updated comprehensive review on chemistry, pharmaceutical uses, and toxicity. Polymers (Basel) 13, 1–22 (2021).

Tietel, Z., Kahremany, S., Cohen, G. & Ogen-Shtern, N. Medicinal properties of jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis). Isr. J. Plant Sci. 26, (2021).

Blaak, J. & Staib, P. Medicinal properties of jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 44, 1–9 (2022).

Al-Obaidi, J. R., Halabi, M. F., AlKhalifah, N. S. & Asanar, S. A review on plant importance, biotechnological aspects, and cultivation challenges of jojoba plant. Biol Res 50, 25 (2017).

Dager, A., Uchida, T., Maekawa, T. & Tachibana, M. Synthesis and characterization of mono-disperse carbon quantum dots from fennel seeds: Photoluminescence analysis using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 9, 14004 (2019).

Cao, X. et al. One-pot synthesis of carbon dots/hydrochar and visible-light-driven photocatalysts for aerobic oxidative coupling of benzylic amines. Chem. Synth. 5, 5 (2025).

Cao, X. Zhao, Y. Leng, J. Bai, X. Qu, Y. Jiang, L. Chen, D. & Wang, J. One-pot synthesis of carbon dots/hydrochar and visible-light-driven photocatalysts for aerobic oxidative coupling of benzylic amines. Chem. Synth. 5 (2025).

Liu, T., Cui, Z. W., Zhou, J., Wang, Y. & Zou, Z. G. Synthesis of pyridinic-rich N, S co-doped carbon quantum dots as effective enzyme mimics. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 12, (2017).

Mousavi, H., Ghomshe, S. M. T., Rashidi, A. & Mirzaei, M. Hybrids carbon quantum dots as new nanofluids for heat transfer enhancement in wet cooling towers. Heat Mass Transf./Waerme- Stoffuebertragung 58, 309–320 (2022).

Abbas, A., Tabish, T. A., Bull, S. J., Lim, T. M. & Phan, A. N. High yield synthesis of graphene quantum dots from biomass waste as a highly selective probe for Fe3+ sensing. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–16 (2020).

Wang, R., Wang, X. & Sun, Y. One-step synthesis of self-doped carbon dots with highly photoluminescence as multifunctional biosensors for detection of iron ions and pH. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 241, 73–79 (2017).

Hashem, H. M. El-Maghrabey, M. Borg, H. Magdy, G. Belal, F. & El-Shaheny, R. Room-temperature upcycling of agricultural waste to carbon dots and its application as a selective fluorescence nanoprobe for iron (III) analysis in diverse samples. Talanta 12, (2025).

Cappello, V. et al. Ultrastructural characterization of the lower motor system in a mouse model of krabbe disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 1 (2016).

Khan, Z. M. S. H., Rahman, R. S., Shumaila, I. S. & Zulfequar, M. Hydrothermal treatment of red lentils for the synthesis of fluorescent carbon quantum dots and its application for sensing Fe3+. Opt. Mater. (Amst) 91, 386–395 (2019).

Latief, U., ul Islam, S., Khan, Z. M. S. H. & Khan, M. S. A facile green synthesis of functionalized carbon quantum dots as fluorescent probes for a highly selective and sensitive detection of Fe3+ ions. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 262, 120132 (2021).

Lakowicz, J. R., Prendergast, F. G. & Hogen, D. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements under oxygen quenching conditions as a method to quantify the depolarizing rotations of fluorophores. Application to diphenylhexatriene in isotropic solvents and in lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 18, 520–527 (1979).

Mousa, M. A., Abdelrahman, H. H., Fahmy, M. A., Ebrahim, D. G. & Moustafa, A. H. E. Pure and doped carbon quantum dots as fluorescent probes for the detection of phenol compounds and antibiotics in aquariums. Sci. Rep. 13, 12863 (2023).

Acknowledgements

W.S.M expresses his gratitude to JICA for the TICAD7 scholarship.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The work was supported by Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF) in Egypt through project No 46176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohsen Ghali; Conceptualization, methodology, review, editing and project supervisor. W.S Mabior; Methodology and draft writing. H. Soliman; NMR data analysis and interpretation and revised editing. M.Sami, Methodology, M. K. Elnimr; Conceptualization, review, editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghali, M., Mabior, W.S., Soliman, H. et al. Ultrasensitive optical detection of Fe3+ ions using fluorescent carbon quantum dots derived from Simmondsia Chinensis Jojoba leaves. Sci Rep 15, 40375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25214-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25214-x