Abstract

Computer vision is increasingly used in manufacturing to ensure high-quality products and reduce cost. In Directed Energy Deposition-Arc (DED-Arc) processes, challenges like dimensional inaccuracy, layered morphology, and metallurgical flaws require online monitoring. This paper presents a method to predict arc and melt pool areas during layer deposition using computer vision. Pareto optimization is applied to analyze how melt pool area changes with arc area. The strong and weak arc classification has been determined using Inception V3. The two different variations of arc and melt pool area in a pulsed DED-Arc process are considered by calculating the mean of both the arc/ melt pool area in each of the single pulse cycles. The segmentation accuracies of the arc and melt pool area are found as more than 95 percent, which is validated using the proposed Convolution Neural Network(CNN) architecture in this research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The manufacturing landscape is undergoing a significant transformation with the adoption of additive manufacturing (AM) technologies, which offer distinct advantages over conventional subtractive manufacturing (SM). These include reduced material waste, enhanced part customization, small-batch production without specialized tooling, and shorter lead times contributing to a more efficient supply chain1,2,3. Among AM methods, Directed Energy Deposition (DED) has gained prominence due to its ability to fabricate complex geometries, repair existing components, and minimize material waste. The growing demand for customized, sustainable, and cost-effective production solutions has accelerated the adoption of DED across diverse industries. DED techniques are primarily classified based on the energy source employed: laser-based DED, electron-beam DED, and arc-based DED. Among these, the DED-arc process is particularly advantageous for fabricating large components because of its relatively higher deposition rate and shorter build time compared to the other two methods4.

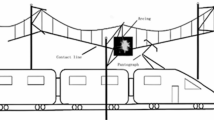

In a DED-arc, a metal wire serves as the feedstock, which is melted by an electric arc and deposited layer by layer, adhering to the fundamental principles of DED. The process is typically carried out in an inert gas environment to protect the molten pool from oxidation and ensure consistent deposition. In gas metal arc-based DED (GMA-DED), key process parameters include arc current and voltage, wire feed rate, and deposition head travel speed. These parameters critically influence process stability, bead geometry, dimensional accuracy, and the structural and mechanical properties of the manufactured parts. As illustrated in Fig. 1 the deposition process involves feeding metal wire from a spool while maintaining precise motion of the deposition head. A controlled gas metal arc provides the necessary heat to melt the wire, and the molten metal solidifies following the principles of heat and mass transfer[ref]. Table 1 summarizes the interrelationships between DED-arc process parameters and their influence on bead geometry, distortion, deformation, and melt pool dynamics. Variations in these parameters, along with external disturbances, can significantly affect process stability. Hence, adaptive control and continuous monitoring are required to ensure defect-free manufacturing. Despite its advantages, DED-arc faces several challenges that hinder large-scale industrial deployment. High heat input can induce residual stresses and thermal distortion, while irregular melting and solidification may result in porosity and lack of fusion5,6,7. Additionally, surface roughness often necessitates costly post-processing to meet functional requirements. Pulsed wire arc DED is increasingly applied for the fabrication and repair of large-scale, low-cost metal components in aerospace, marine, automotive, and defense sectors. However, its inherently unstable arc behavior, variable melt pool dynamics, and high thermal gradients make it highly sensitive to process fluctuations. Such fluctuations frequently lead to defects, including:

-

Irregular layer heights

-

Inconsistent melt pool shapes

-

Surface roughness and distortion

-

Porosity and lack of fusion

To mitigate these issues, a quantitative and automated monitoring strategy is required to capture the geometrical evolution of the arc and melt pool across pulse cycles, correlate these observations with deposition behavior, and guide parameter adjustments in real time8. Although process optimization can improve outcomes, the non-linear and dynamic nature of DED-arc means that optimized parameters alone cannot fully eliminate defects.

Consequently, real-time monitoring has emerged as a critical approach for enhancing process stability, predicting dimensional deviations, and ensuring part quality9. Suitable sensors—ranging from high-speed cameras to pyrometers, infrared imaging systems, and current/voltage sensors—enable dynamic feedback and adaptive corrections during fabrication10. Furthermore, integrating predictive analytics with sensor data can facilitate closed-loop control, reduce post-processing requirements, and improve overall manufacturing reliability. The subsequent sections provide a detailed discussion on the role of sensors and real-time monitoring techniques for DED-arc processes. Table 2 below outlines the process, algorithms used, accuracy, limitations, and references for each of the key studies on real-time monitoring of arc behavior in Directed Energy Deposition-Arc (DED-Arc) systems. This survey highlights the diverse methodologies employed for real-time monitoring of arc behaviour in DED-Arc systems.

Recent advancements in Directed Energy Deposition using Arc (DED-Arc) have demonstrated the potential of real-time monitoring to enhance process stability and part quality10,13,14,15,32. However, existing approaches often rely on simplified geometric approximations, such as Gaussian or ellipsoidal fitting19,33,34,35, which may not fully capture the transient behaviors of the arc and melt pool under fluctuating process conditions. Furthermore, while segmentation techniques and deep learning models have been employed to analyze process images13,14,15,18,32, limited work has been reported on quantitatively correlating geometric variations with process dynamics and deposition quality19,24,36,37.

This study addresses this gap by presenting a quantitative method to monitor and predict the dynamic geometries of both the arc and melt pool during each pulse cycle of the DED-Arc process. The method calculates mean arc and melt pool areas per pulse cycle, capturing temporal variations more accurately than conventional techniques. To ensure high segmentation accuracy and reliability, a custom-designed Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is employed. CNNs are particularly effective for this task because of their superior ability to extract hierarchical spatial features, robustness to glare and process-induced noise, and capacity for pixel-level precision in delineating complex arc and melt pool boundaries . Moreover, CNN-based architectures generalize well across diverse process conditions and can operate at near real-time inference speeds, making them suitable for adaptive manufacturing scenarios. Subsequently, Pareto optimization is applied to establish correlations between variations in arc area and corresponding changes in melt pool area, thereby elucidating the influence of input process parameters on critical output features. In addition, the approach correlates geometric features with layer height variation, providing predictive insights into deposition quality and enabling improved process understanding. Though the surface finish, residual stress and thermal deformation are three major influencing features other than arc and melt pool stability, the scope of the present study is limited to enhance the arc segmentation and arc area detection accuracy . The scope will be wider in future via inclusion of thermal deformation and residual stress prediction for recommending the suitable post-processing technique. By integrating accurate geometric quantification, deep learning-based segmentation, and multi-objective optimization, this work not only enhances real-time monitoring of DED-Arc but also lays the foundation for future closed-loop control systems aimed at minimizing defects and improving manufacturing reliability.

The manuscript is organized into several sections for clarity. “Experimental set up” covers the experimental setup of DED-Arc system. “Proposed methods” outlines the proposed methodology. “Analysis of arc and melt pool area” covers the detailed analysis of the arc and melt pool area respectively. Finally, “Conclusion” presents the conclusions and discusses potential directions for future work.

(a) Experimental set up(top), (b) deposited wall(middle), and (c) process zone (bottom) of DED-Arc system8.

Experimental set up

The DED-Arc experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2 a8. The deposited wall produced during the DED-Arc process is given in Fig. 2b8. The detailed diagram of the process zone is described in Fig. 2c8. This study focuses on finding the areas of molten pool in different layers of DED-Arc samples. ABB robot with 6 DOF, ABB wire feeder, Fronius TPS 320i GMAW setup, vision sensing system, and computer represent the majority of the machine8.

The experimental configuration and process set up for DED-Arc has been discussed in Table 3. Process parameters are summarized in Table 4. A pulse frequency of 0.5 Hz is used in the two-step pulse mode of metal transfer. It is adjusted at 0.60 for the process duty cycle (DC). The mean current (Im) is calculated using the conventional correlation \(Im = (Iptp + Ibtb)/(tp + tb)\), where \(tp = DC/f\) and \(tb = (1 - DC)/f\). During the deposition, shielding gas is used at 20 l/min of pure 99.99 percent argon gas. The raw material for the deposition is 1.2 mm-diameter IN625 (AWS NiCrMo-3) filler wire, which is easily accessible.

During deposition, a shielding gas flow rate of 20 l/min of 99.99% pure argon was maintained. The filler wire used was a commercially available 1.2 mm diameter IN625 (AWS NiCrMo-3), widely used in DED-Arc processes for its excellent weldability and mechanical properties.

Capturing dynamic arc and melt pool behavior

Our experimental setup incorporates a high-speed CMOS camera system, operating at 3600 frames per second (FPS), with appropriate optical filtering and controlled exposure time to capture arc and melt pool behavior within each pulse cycle. This temporal resolution, while not sufficient to resolve every microsecond-scale transient event of the arc plasma, is capable of capturing the following:

-

(i)

Pulse-to-pulse variations in arc morphology, and

-

(ii)

Gradual evolution of the melt pool boundary across the deposition sequence.

To reflect this, our image analysis, extracts area and shape features on a per-frame basis, which are then aggregated over defined temporal windows (e.g., over each pulse cycle or deposition segment) to compute mean, standard deviation, and trend-based statistics.

Thus, while the molten pool does not exhibit rapid oscillations within a single current pulse, our configuration captures the cumulative dynamic evolution over time—sufficient for detecting trends, anomalies, or shifts in geometric stability. This temporal resolution aligns with the industrial requirement for near-real-time monitoring rather than ultra-fine plasma diagnostics, which would require spectroscopic or ultra-high-speed imaging equipment not feasible in most production environments.

Vision sensing system design

The vision sensor system comprises a high-speed camera (Photron Fastcam Mini AX200), a zoom lens (Navitar 7000), an 11 A1 DIN glass, and a sheet glass. The tripod-mounted camera was held perpendicular to the longitudinal direction of deposition. The lens’s aperture is 5.6, its focal length is 108 mm, and the camera’s frame rate is 3600 fps. The camera captured photos at a resolution of 704 x 226 pixels in 8-bit color. The distance between the lens and the deposit was maintained at 326 mm. A glass panel was placed between the camera and the substrate to shield it from spills and fumes. The number of sample images is around 10000 for different layers of single-wall deposition. A new method has been created in this research work to estimate the area of the arc and molten pool.

Our vision-based monitoring system operates concurrently with the deposition, passively collecting and analyzing high-speed image data in real time. Although our results are statistically processed (e.g., mean arc/melt pool area per pulse or layer), they are derived directly from in-process image frames, not from post-deposition inspection or offline metrology. Hence, the monitoring and analysis are consistent with widely accepted definitions of in-situ sensing in manufacturing literature.

Dataset description

Approximately 10,000 images of both strong and weak arcs are available for various layers of single-wall deposition. Each layer contains around 1600 arc images. There are 20 deposition layers for each of exp.1, exp.2, exp.3, exp.4, and exp.5, respectively. The images captured by high-speed cameras are converted into grayscale images. The grayscale values are 0 to 255, where 0 denotes complete black and 255 denotes complete white. The grayscale value of 255 is detected for the strong arc portion in the images. For every cycle, the strong and weak arc intensities are calculated.

In our study, images were captured at 3600 fps, and from each current pulse cycle, both strong-arc and weak-arc images were extracted. Each pulse provides two representative images—one during the strong arc phase and another during the weak arc phase. For each layer, approximately 1600 arc images were obtained after removing blank frames. With 20 layers per experiment across five experimental conditions, the dataset comprises nearly 10,000 images. Among these, weak-arc images correspond to the lower-intensity phase of each pulse, while strong-arc images correspond to the higher-intensity phase.

This systematic pulse-wise acquisition ensures that both arc states are consistently represented, providing balanced data for segmentation and analysis. The final dataset size thus reflects the cumulative count of images across all layers, pulses, and experimental conditions, ensuring statistical reliability.

Proposed methods

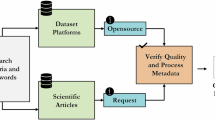

In this study, the methodology of determining the area of the arc and melt pool from the images has been depicted in Fig. 3.

Methods

The images of the arc and melt pool area of both strong and weak arcs have been captured with the high-speed camera. The extraction of strong and weak arcs based on intensity is described in Fig. 6. The classification of images of strong and weak arcs has been determined by applying Inception V3. The two different arc variations of strong and weak arc in the case of both arc and melt pool area for pulsed DED-Arc process have been considered by calculating the mean of the melt pool/arc areas of strong and weak arc in a single pulse cycle. The melt pool and arc area can be measured through online monitoring. The methodology for classifying images of the strong and weak arc is described in “Classification of images using Inception V3”.

Extracting strong and weak arc images

The strong arc’s intensity range is found to be between 20 and 25 lm, while the weak arc’s intensity range is between 5 and 10 lm. This allows the images of the weak and strong arcs to be separated for further analysis. The images of weak and strong arcs are described in Fig. 4.

The boundary between the arc and molten pool in Fig. 4 was determined using a physics-informed image processing strategy that leverages both the temporal and spatial intensity distribution of the arc. During weak-arc phases, the molten pool region is clearly distinguishable, and its contours were extracted using adaptive thresholding. In strong-arc phases, where saturation occurs, the interface is identified from the sharp inflection in pixel intensity gradients, which physically corresponds to the steep thermal gradient at the transition from the high-temperature arc plasma to the relatively cooler molten pool surface. To ensure robustness, the molten pool mask from weak-arc frames was integrated with edge-based contours from strong-arc frames, producing a consistent and reproducible boundary across pulse cycles. This combined approach ensures that the boundary is not subjectively drawn but objectively derived from measurable thermal and optical features inherent to the process. As shown in Fig. 5 the arc–melt pool boundary was identified from the inflection zone of the pixel intensity profile, which corresponds to the sharp thermal gradient between the high-temperature arc plasma and the molten pool surface.

Classification of images using Inception V3

Strong and weak arcs can be identified by the images acquired by a high-speed camera. The data set contains 10000 images, and each layer contains around 1600 arc images. However, the classification of strong and weak arcs has been determined using Inception V3, a deep-learning model based on CNN. Fig. 8a and Fig. 8b describe the classification of strong and weak arcs using Inception V3. The inception V3 model provides an accuracy above 95 percent, and the loss is below 10 percent as provided in Fig. 8c. The block diagram is described in Fig. 7. Inception V3 has been used in this work to classify the images of strong and weak arcs.

Eradication of blank images from the arc images

Many blank images are also acquired since the image is captured at 3600 fps. The first goal is to remove those blank images from each layer’s list of arc images. From nearly 10000 images of each layer only about 1600 arc images were extracted.

Automatic selection of region of interest (ROI)

The arcing region is the zone of interest in the raw image with a dimension of 704 x 226 pixels. The ROI was created by taking a smaller portion of the raw image, including the wire electrode, the arcing zone, the molten pool area, and a small cropped background. As a result, the computation time can be sped up, and accurate measurement can be performed.

Application of Gaussian fit for the arc area

The Gaussian filter is a popular low-pass filter for eliminating high-frequency elements from images. Electron overflow on the camera sensor can occur during the taking of images, especially ones with strong arcs, and cause glare. As such, removing glare is essential, particularly for strong arcs. Therefore, the images are smoothed and glare and noise are removed using a 2-dimensional Gaussian filter,

where, \(G(x,y)\) stands for the Gaussian function, \(\sigma\) stands for the standard deviation, and \(x\) and \(y\) for the horizontal and vertical dimensions of Gaussian Kernel respectively38. Equation (1) describes the 2-dimensional Gaussian function. The images of arc area before and after gaussian filter have been described in Fig. 9

Application of ellipsoidal curve for the meltpool area

The ellipsoidal curve has been applied in order to determine the melt pool area. The area has been determined by using the formula

, where \(a\), \(b\) are semi major and semi minor axis respectively39. The images of melt pool area before and after ellipsoidal curve have been described in Fig. 10

Edge detection and thresholding

The arc and molten pool region are then extracted from the image using thresholding techniques. Segmentation is applied to the images. This is accomplished by thresholding the image and binarizing it. This method is used in conjunction with the Otsu thresholding and Simple(manual) thresholding to determine the bounding edge of the melt pool and arc region. The arc and melt pool area have been extracted by using both Otsu and Simple thresholding. After that, the mean value of the melt pool/arc area has been considered. In this work, by calculating the mean area of the arc and melt pool throughout each distinct pulse cycle, a proprietary area computation methodology captures the intrinsic temporal changes caused by variable process parameters. The regions of interest of arc area before and after applying thresholding have been described in Fig. 11a, b respectively. The regions of interest of melt pool area before and after applying thresholding have been described in Fig. 12a, b respectively.

Calculation of proposed area of arc and melt pool area

In this study, the layer wise changes in the arc and molten pool area along with the changes of the process parameters have been discussed. However, the area of the arc and molten pool are calculated as

, where \(pi\) is the pixels. It has been found that the area of arc and melt pool calculated by applying proposed area calculation is more accurate than the arc area calculated by applying gaussian fit and the melt pool area calculated by applying ellipsoidal curve respectively. The details of the arc and melt pool area calculated by applying gaussian fit, ellipsoidal curve and proposed area calculation respectively are described in Table 11.

Methodology of area calculation

Equation (3) represents the core formulation of our area calculation methodology. While the operation of summing pixel values within a segmented region is mathematically straightforward, the novelty lies in the design and integration of a real-time-capable, adaptive, and noise-resilient pipeline tailored for pulsed DED-Arc environments.

This methodology introduces several innovations over conventional approaches:

Process-aware calibration: unlike traditional geometric approximations (e.g., ellipsoidal or Gaussian models), our method integrates segmented pixel regions derived from high-speed imaging and dynamically adapts to real-time arc behavior. The region of interest (ROI) is adjusted per frame based on arc location and melt pool dynamics, which allows for accurate area estimation even in the presence of spatter, glare, or partial arc occlusion.

Temporal resolution at pulse level: area calculations are performed at the level of individual pulse cycles, enabling the tracking of frame-wise fluctuations in arc and melt pool geometries. These temporal measurements are then aggregated to derive statistical indicators (mean, standard deviation), allowing for robust trend detection and noise suppression.

Deep learning-enabled mask precision: the area calculation relies on high-fidelity binary masks generated using our custom-trained CNN segmentation model. This ensures precise delineation of arc and melt pool boundaries, and therefore pixel-perfect integration—achieving higher accuracy than traditional thresholding or edge-detection techniques.

Validation and superiority over conventional fits: as presented in Table 11, our method achieves significantly lower mean square errors in melt pool area estimation compared to ellipsoidal and Gaussian fitting approaches. The latter methods rely on idealized assumptions, which tend to overpredict area due to their inability to capture real-time process fluctuations. In contrast, our method is grounded in observed data and validated against manually verified ground truth masks.

In summary, while Eq. (3) defines the computational formula, the proprietary innovation lies in the full methodology’s ability to operate accurately in dynamic deposition environments, providing real-time, geometry-aware insights crucial for predictive monitoring and adaptive control in DED - Arc systems.

Application of deep learning for determining the segmentation accuracies of arc and melt pool area

Inception V3 has determined the classification of strong and weak arcs. There are two input labels for strong and weak arcs: zero and one, respectively. The images of strong and weak arcs have been classified at various layers of the melt pool and arc area. The values of arc and melt pool areas fluctuate at different levels. The deviations in the regions of the various layers result from variations in the process parameter values, such as travel speed, current, voltage, heat, etc. In this work the backpropagation has been implemented for updating the weights of each layer for the arc and melt pool area, and segmentation accuracies of the images of the melt pool and arc area is validated with the help our proposed CNN architecture. Table 5 describes our proposed CNN architecture. The two distinct arc variations for the arc and melt pool area of the pulsed DED-Arc process have been considered by taking the mean of the melt pool/arc area in a single pulse cycle. However, the segmentation accuracies of the arc and melt pool area have been achieved from several layers of the DED-Arc process (Fig. 13).

Method comparison, system optimization

This work introduces a pixel-wise area calculation method derived from CNN segmentation masks to quantitatively analyse arc and melt pool dynamics in the A-DED process. Unlike classical geometric approximation techniques such as Gaussian or ellipsoidal fitting, our approach does not rely on assumptions about melt pool symmetry or boundary shape. To evaluate the accuracy and reliability of this method, we performed a comparative analysis with Gaussian and ellipsoidal fitting models. The CNN-based segmentation demonstrated significantly higher fidelity in capturing non-uniform melt pool geometries, particularly under high-glare and pulsating arc conditions. Quantitative performance metrics, including Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and mean absolute error (MAE), revealed that the proposed method outperforms classical approximations by 12–18 percent in MAE. Table 6 describes the comparison of Segmentation Accuracy. Table 7 describes the MAE vs Ground truth. It quantifies the error reduction achieved by CNN segmentation. Figure 14 describes the boundary extraction comparison. A qualitative overlay of predicted boundaries against ground truth, highlighting CNN’s ability to follow irregular melt pool shapes more closely have been discussed.

However, to achieve high segmentation accuracy and reliability, a custom-designed Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was employed. Its hierarchical feature extraction enables robust handling of glare and process-induced noise while ensuring pixel-level precision in delineating arc and melt pool boundaries. In addition, the architecture generalizes effectively across varying process conditions and supports near real-time inference, making it well-suited for adaptive manufacturing applications.

By integrating a weld camera(which is costly) with the robotic arm, the melt pool can be captured with higher precision, allowing its area to be directly incorporated into the existing processing framework. Furthermore, the use of two cameras—one dedicated to arc monitoring (as in the present method) and another focused on the melt pool—would enable simultaneous measurement of both regions from the top view. This dual-camera configuration ensures more accurate characterization of arc and melt pool dynamics, thereby enhancing process understanding and enabling better optimization of their combined contributions to deposition quality. This could be implemented in future work.

Analysis of arc and melt pool area

Fundamental DED-Arc equation and dynamic instability

In a pulsed wire arc DED process, the arc and melt pool dynamics are governed by the balance of electrical, thermal, and fluid forces. The arc energy input per unit length can be expressed as:

where I is the arc current (A), V is the arc voltage (V), and v is the torch travel speed (mm/s).

The corresponding melt pool area is proportional to the net heat flux absorbed by the substrate:

where \(\eta\) is the process efficiency factor and \(\kappa \nabla T\) represents heat loss by conduction and convection. Since I(t) and V(t) vary in pulsed mode, the melt pool area exhibits temporal fluctuations.

Similarly, the arc length dynamics can be expressed as:

where \(L_0\) is the nominal arc length and \(\Delta L(t)\) denotes temporal deviations due to pulsed current and wire feed variations.

Dynamic instability effect

Equations (4)–(6) indicate that fluctuations in current and voltage induce oscillations in \(H_I\), \(A_{\text {melt}}(t)\), and \(L_a(t)\). Small deviations in arc length increase heat loss and destabilize the arc–melt pool interface. This leads to irregular melt pool geometry, fluctuating layer heights, and non-uniform bead widths.

From an additive manufacturing perspective, these results confirm that real-time monitoring and prediction of \(A_{\text {arc}}\) and \(A_{\text {melt}}\) are essential to mitigate dynamic instabilities and to optimize deposition quality (Fig. 15).

Table 8 describes the manually calculated area and the predicted area. This study presents layer-by-layer images of the arc and molten pool areas under varying process parameters, with results summarized in Tables 9 and 10. The focus is on quantifying these areas using a proprietary calculation method that computes mean values per pulse cycle, capturing temporal variations more effectively than Gaussian or ellipsoidal fitting. This robust approach accurately reflects transient behaviors during the DED-Arc process. Segmentation accuracy is validated using a custom CNN, with delta values for both arc and melt pool areas obtained via backpropagation.

Figures 16a–e show arc and melt pool images for Exp.1–Exp.5, while Figures 17a–e and Figures 18a–e present segmentation accuracy for melt pool and arc areas, respectively.

For instance, in Exp.1, the arc area is 38.65 mm\(^2\) with process parameters of 92A current, 19.2V voltage, 11 mm/s travel speed, 3.5 m/min WFS, and 0.1284 kJ/mm heat input; the delta value is 0.46 and segmentation accuracy is 96%. In Exp.2, the arc area is 44.15 mm\(^2\) with parameters of 92A, 19.2V, 9 mm/s, 3.5 m/min, and 0.15701 kJ/mm; the delta value is 0.35.

The segmentation accuracy of the arc area across experiments ranges from 90% to 96%, with validation loss consistently below 10%. In Exp.3, the parameters (141A, 21V, 11 mm/s, 5.5 m/min, 0.24226 kJ/mm) yield a predicted arc area of 50.61 mm\(^2\) (approx.), a delta value of 0.12, and 96% accuracy. In Exp.4, parameters (141A, 21V, 9 mm/s, 5.5 m/min, 0.29611 kJ/mm) produce a 53.62 mm\(^2\) arc area, delta 0.14, and 96% accuracy. In Exp.5, parameters (191A, 22.7V, 11 mm/s, 7.5 m/min, 0.31532 kJ/mm) yield a 59.55 mm\(^2\) arc area, delta 0.44, and 90% accuracy.

Similarly, melt pool segmentation accuracy ranges from 91% to 98%, with validation loss below 10% for all cases. In Exp.1 (92A, 19.2V, 11 mm/s, 3.5 m/min, 0.1284 kJ/mm), the melt pool area is 32.21 mm\(^2\), delta 0.42, accuracy 98%. In Exp.2 (92A, 19.2V, 9 mm/s, 3.5 m/min, 0.15701 kJ/mm), the area is 35.89 mm\(^2\), delta 0.31, accuracy 97%. In Exp.3 (141A, 21V, 11 mm/s, 5.5 m/min, 0.24226 kJ/mm), the area is 43.49 mm\(^2\), delta 0.8, accuracy 98%. In Exp.4 (141A, 21V, 9 mm/s, 5.5 m/min, 0.29611 kJ/mm), the area is 46.04 mm\(^2\), delta 0.10, accuracy 96%. In Exp.5 (191A, 22.7V, 11 mm/s, 7.5 m/min, 0.31532 kJ/mm), the area is 51.98 mm\(^2\), delta 0.40, accuracy 91%.

Figures 17a–e and 18a–e show that the x-axis duration varies (16–30) due to early callback functions, as noted in “Vision sensing system design”. From Table 9, the final updated weights and delta value for arc area are 0.5192 and 0.15, respectively, while Table 10 shows 0.4892 and 0.12 for melt pool area. Both areas change significantly with current, travel speed, and heat input, and at constant heat input, they increase proportionally. Thus, arc and melt pool areas are directly related and vary layer-wise with process parameters, as detailed in “Correlation of process parameters with melt pool and arc area”.

Comparative study of arc and melt pool area using gaussian fit, ellipsoidal curve and proposed area calculation

In this study, a cropped region of interest (ROI) containing the wire electrode, arc zone, molten pool, and minimal background was extracted from raw images. Both arc and melt pool regions were thresholded, segmented into pixels, and their areas calculated using the proposed methodology. For comparison, Gaussian fitting (arc) and ellipsoidal fitting (melt pool) were also applied, and the mean square error (MSE) was computed as:

where \(a\) is the area from Gaussian/Ellipsoidal fitting and \(b\) is from the proposed method .

Table 11 show that the proposed calculation consistently yields areas closer to actual dimensions, with lower MSE for the arc compared to the melt pool across all experiments. For example, in Exp. 1, the arc MSE was 3.38, while the melt pool MSE was 19.78. Overall, melt pool errors were generally higher due to its complex boundary, but the proposed method significantly reduced overprediction compared to conventional fits. Figure 19 illustrates the percentage overestimation for both arc and melt pool areas, highlighting the improved accuracy and robustness of the proposed approach.

This section summarizes the key outcomes of segmentation, area prediction, and process optimization in a concise and structured format.

Segmentation accuracy and validation

The CNN model trained on 6, 500 annotated images achieved a segmentation accuracy between \(91\%\) and \(98\%\) across five deposition scenarios. Ground truth masks were verified manually to ensure pixel-level precision. Validation loss remained below \(10\%\) across all cases. Table 9 and Table 10 summarizes these metrics concisely.

Comparison with traditional methods

Figure 14 and Table 11 present a comparative evaluation of our proprietary area computation method versus Gaussian and ellipsoidal fitting. Our method consistently outperformed others with lower MSE and better alignment with physically measured melt pool areas. These findings validate the suitability of our pixel-wise segmentation-based approach for real-time monitoring.

Area-height correlation and process monitoring

Correlation between melt pool area and deposited layer height was analyzed, showing a linear relationship (\(R^2 > 0.9\)) across varying arc conditions. This confirms the predictive utility of vision-derived area data for build quality assessment.

Pareto optimization

In this study, Pareto optimization was employed to balance the influence of process parameters on arc stability and melt pool geometry. In DED-Arc system, higher heat input enhances bonding but increases melt pool size, potentially compromising geometric precision, while lower heat input maintains dimensional stability but may reduce fusion quality. By applying Pareto optimization, we identified a set of parameter configurations (e.g., welding current, wire feed rate, and travel speed) that optimally balance these conflicting objectives, maximizing arc stability and melt pool consistency under given constraints. This multi-objective approach yields a Pareto front of non-dominated solutions, providing scientifically robust operating conditions rather than a single, potentially biased result. These optimized parameters ensure stable arc behavior and consistent melt pool geometry, both critical for achieving high layer quality and dimensional accuracy. By adopting this systematic framework, the reported process conditions are derived from rigorous multi-objective optimization, enhancing reproducibility and informing advanced process control strategies. Fig. 21 a describes the correlation graph of arc and melt pool area using pareto analysis.

Correlation of process parameters with melt pool and arc area

Analysis of Tables 9 and 10 shows that both arc and melt pool areas are strongly influenced by travel speed, heat input, and current. For instance, comparing Exp. 1 and Exp. 2, a decrease in travel speed (11 to 9 mm/s) and an increase in heat input (0.12847 to 0.15701 kJ/mm) result in larger arc (38.65 to 44.15 mm\(^2\)) and melt pool areas (32.21 to 35.89 mm\(^2\)). Similarly, in Exp. 4 and Exp. 5, higher current (141 to 191 A) and heat input correlate with increased arc (53.62 to 59.55 mm\(^2\)) and melt pool areas (46.04 to 51.98 mm\(^2\)).

Figure 20a–c further quantify these trends. Heat input shows a clear linear relationship with melt pool area (intercept: 20.51, slope: 93.97, residual sum of squares: 9.23). Current exhibits a stronger influence on both arc and melt pool areas than travel speed, indicating that electrical parameters play a dominant role in governing deposition geometry.

On the other hand, in Fig. 21a, the arc area and melt pool area has been plotted in the x and y axes, respectively. Figure 21b shows a curve generated along the x and y axes, respectively.

Maximum mean value (Fig. 21a): the frame with the highest recorded mean grayscale intensity in the segmented melt pool, indicating greater thermal radiation, larger melt pool size, and higher heat input, typically resulting from increased arc energy or parameters such as higher current and wire feed rate.

Minimum mean value (Fig. 21b): the frame with the lowest mean grayscale intensity, corresponding to reduced arc energy, smaller melt pool size, and lower heat input, generally arising from lower input parameters or a less stable arc.

The contrast between these subfigures reflects variations in deposition conditions that directly influence arc intensity, melt pool dimensions, and thermal energy distribution. The melt pool segmentation algorithm captures these dynamic changes, and the selected subfigures illustrate the range and sensitivity of the vision-based system to such variations. The molten pool and arc areas range from 10.14 to 84.61 mm\(^2\) and 17.22 to 96.46 mm\(^2\), respectively, with mean values spanning 13.68 to 90.54 mm\(^2\). Figure 21b plots arc area (x-axis) against melt pool area (y-axis), revealing a clear proportional relationship confirmed through image processing, backpropagation algorithms, and Pareto optimization. These results highlight the need for online monitoring and control to track variations in molten pool dimensions during deposition.

In addition to the current pixel-wise segmentation approach, several real-time capable techniques can be considered to further improve recognition accuracy of the melt pool area. Deep Learning–based Semantic Segmentation (e.g., U-Net, SegNet, DeepLab) trained on melt pool datasets can achieve higher robustness under arc glare and spatter conditions. Adaptive Thresholding with Morphological Filtering, which dynamically adjusts to varying brightness, ensures more stable contour extraction. Optical Flow–based Tracking, where consecutive frame correlation is used to smooth the melt pool boundary, reduces frame-to-frame noise. Sensor Fusion Methods, integrating thermal imaging with visible-light data, can reduce misclassification caused by reflection and glare. Edge-Attention CNNs, which explicitly focus on the boundary of the melt pool, enhance accuracy for real-time monitoring and control. These improvements enable more reliable real-time monitoring, laying the foundation for closed-loop control of bead geometry and process stability in DED-Arc.

Validation

In this study, the vertical distance between the boundaries of two consecutive layers was measured to calculate the average layer height from arc and melt pool images. For each pair of layers (e.g., layer N and \(N+1\)), the pixel-wise vertical distance was computed. Variations in process parameters caused changes in the arc and melt pool areas, which directly influenced the average layer height—larger arc and melt pool areas resulted in higher average layer heights.

The proposed area calculation method enables real-time monitoring of arc and melt pool areas, process parameter variations, and corresponding changes in layer height. Figure 22a shows the variation of average layer height with arc and melt pool areas, while Fig. 22b presents the corresponding linear fit. The results indicate a proportional, linear relationship between average layer height and both arc and melt pool areas, with the x-axis representing area (\(\text {mm}^2\)) and the y-axis representing average layer height (mm).

Conclusion

In this study, a high-speed camera is used for continuous monitoring of arc and melt pool areas during layered deposition in a pulsed DED-Arc process. A new methodology is developed to calculate these areas by averaging measurements within each pulse cycle. The approach is validated using a customed Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model to improve segmentation accuracy and Inception V3 for classifying strong and weak arcs. The key findings are as follows:

-

Both arc and melt pool areas increase by at least 3% when current, travel speed, and heat input vary from Exp. 1 to Exp. 5.

-

Compared to Gaussian (arc) and ellipsoidal (melt pool) fits, the proposed method reduces error by at least 3% for the arc and 4% for the melt pool, lowering MSE for arcs to below 10. Overprediction is limited to 0–8% for arcs and 0–20% for melt pools.

-

A proportional relationship between arc and melt pool areas is confirmed through image processing, backpropagation algorithms, and Pareto optimization. Increased melt pool area benefits high-speed, large-scale builds (e.g., aerospace and automotive), while increased arc area enhances deposition rates.

-

Average layer height shows a linear dependence on both arc and melt pool areas, enabling manufacturers to monitor and adjust these parameters in real time for consistent quality. In addition, the method links geometrical features with layer height variation, to offer predictive insights into deposition quality and to strengthen process understanding.

The proposed vision-based monitoring and prediction system can be integrated with closed-loop control architectures, allowing real-time adjustment of parameters such as wire feed speed, travel speed, or arc current to maintain dimensional fidelity. Continuous online monitoring, combined with deep learning, enables accurate prediction of molten pool behavior without handcrafted features. While surface finish, residual stress, and thermal deformation are also key factors influencing performance alongside arc and melt pool stability, the present study focuses specifically on improving arc segmentation and arc area detection accuracies. In future work, the scope will be expanded to include thermal deformation and residual stress prediction, thereby supporting the recommendation of suitable post-processing techniques. By leveraging large datasets from prior welds, these methods can identify patterns linked to quality or defects, supporting real-time quality control. Advances in imaging and machine learning thus provide a robust foundation for future improvements in monitoring and optimizing DED-Arc processes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baker, R. Method of Making Decorative Articles (1925).

Dickens, P. M., Pridham, M. S., Cobb, R. C., Gibson, I. & Dixon, G. Rapid prototyping using 3-d welding. In Proceedings of the 1992 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium. 280–290 (1992).

Spencer, J. D., Dickens, P. M. & Wykes, C. M. Rapid prototyping of metal parts by three-dimensional welding. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 212, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1243/0954405981515590 (1998).

Wacker, C. et al. Geometry and distortion prediction of multiple layers for wire arc additive manufacturing with artificial neural networks. Appl. Sci. 11, 4694. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11104694 (2021).

Boutin, T., Bendaoud, I., Delmas, J., Borel, D. & Bordreuil, C. Development of a machine learning model for deviation from trajectory detection in multi-pass TIG welding in a narrow gap. Welding World 68, 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-023-01626-z (2024).

Bonaccorso, F., Cantelli, L. & Muscato, G. An arc welding robot control for a shaped metal deposition plant: Modular software interface and sensors. IEEE Trans. Indus. Electron. 58, 3126–3132. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2011.2114311 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Coordinated monitoring and control method of deposited layer width and reinforcement in WAAM process. J. Manuf. Process. 71, 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.09.033 (2021).

Banerjee, A., Tiwari, Y., Dutta, S., Mukherjee, M. & Das, S. Investigating the layer-wise arc and melt-pool characteristics of near-substrate wire arc-directed energy deposited nicrmo-3 alloy using image processing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 1, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241301949 (2024).

Xiong, J., Pi, Y. & Chen, H. Deposition height detection and feature point extraction in robotic GTA-based additive manufacturing using passive vision sensing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 59, 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2019.05.006 (2019).

Alcaraz, J. Y. I., Foqué, W., Sharma, A. & Tjahjowidodo, T. Indirect porosity detection and root-cause identification in WAAM. J. Intell. Manuf. 35, 1607–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-023-02128-x (2024).

Chaurasia, P. K., Goecke, S. F. & De, A. Towards real-time monitoring of metal transfer and melt pool temperature field in gas metal arc directed energy deposition. Welding World 67, 1781–1791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-023-01534-2 (2023).

Zhang, H., Wu, Q., Tang, W. & Yang, J. Acoustic signal-based defect identification for directed energy deposition-arc using wavelet time-frequency diagrams. Sensors 24, 4397. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24134397 (2024).

Song, H. et al. A two-stage unsupervised approach for surface anomaly detection in wire and arc additive manufacturing. Comput. Indus. 151, 103994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2023.103994 (2023).

Franke, J., Heinrich, F. & Reisch, R. T. Vision based process monitoring in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). J. Intell. Manuf. 36, 1711–1721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-023-02287-x (2024).

Xia, C., Pan, Z., Li, Y., Chen, J. & Li, H. Vision-based melt pool monitoring for wire-arc additive manufacturing using deep learning method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 120, 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-08811-2 (2022).

Rahman, M. A., Jamal, S., Cruz, M. V., Silwal, B. & Taheri, H. In situ process monitoring of multi-layer deposition in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) process with acoustic data analysis and machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 132, 5087–5101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-13641-5 (2024).

Mu, H. et al. A digital shadow approach for enhancing process monitoring in wire arc additive manufacturing using sensor fusion. J. Indus. Inf. Integr. 40, 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jii.2024.100609 (2024).

Mattera, G. et al. Semi-supervised learning for real-time anomaly detection in pulsed transfer wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 128, 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.07.142 (2024).

Jafari, D., Vaneker, T. H. J. & Gibson, I. Wire and arc additive manufacturing: Opportunities and challenges to control the quality and accuracy of manufactured parts. Mater. Des. 202, 109471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109471 (2021).

Chaurasia, P. K., Goecke, S. F. & De, A. Real-time monitoring of temperature field, metal transfer and cooling rate during gas metal arc-directed energy deposition. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 27, 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621718.2022.2080447 (2022).

Xiong, J., Pi, Y. & Chen, H. Deposition height detection and feature point extraction in robotic GTA-based additive manufacturing using passive vision sensing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 59, 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2019.05.006 (2019).

Wu, Y., Kim, H. & Kang, S. On-chip defective pixel detection and correction for CMOS image sensors. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 23, 503–517 (2013).

Qi, X., Chen, G., Li, Y., Cheng, X. & Li, C. Applying neural-network-based machine learning to additive manufacturing: Current applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Engineering 5, 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2019.04.012 (2019).

Haleem, A. & Javaid, M. Additive manufacturing applications in industry 4.0: A review. J. Indus. Integr. Manag. 4, 1930001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2424862219300011 (2019).

Chaurasia, P. K., Goecke, S. F. & De, A. Towards real-time monitoring of metal transfer and melt pool temperature field in gas metal arc directed energy deposition. Weld. World 67, 1781–1791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-023-01534-2 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Multisensor fusion-based digital twin for localized quality prediction in robotic laser-directed energy deposition. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 84, 102581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2023.102581 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Research on process control of laser-based direct energy deposition based on real-time monitoring of molten pool. Coatings 14, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings14091131 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Towards intelligent monitoring system in wire arc additive manufacturing: A surface anomaly detector on a small dataset. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 120, 5225–5242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-09076-5 (2022).

Chen, L., Yao, X., Feng, W., Chew, Y. & Moon, S. K. Multimodal sensor fusion for real-time location-dependent defect detection in laser-directed energy deposition. In Proceedings of the ASME 2023 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences & Computers & Information in Engineering Conference. Vol. 87295. V002T02A069. https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2023-110284 (2023).

Pandiyan, V., Cui, D., Richter, R., Parrilli, A. & Leparoux, M. Real-time monitoring and quality assurance for laser-based directed energy deposition: Integrating co-axial imaging and self-supervised deep learning framework. J. Intell. Manuf. 36, 909–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-023-02279-x (2025).

Bevans, B. et al. Monitoring and flaw detection during wire-based directed energy deposition using in-situ acoustic sensing and wavelet graph signal analysis. Mater. Des. 225, 111480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111480 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. Machine learning in additive manufacturing: A review. JOM 72, 2363–2377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-020-04155-y (2020).

Wu, D., Wei, Y. & Terpenny, J. Surface roughness prediction in additive manufacturing using machine learning. Int. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Conf. 51371, V003T02A018. https://doi.org/10.1115/MSEC2018-6501 (2018).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2881–2890. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.660 (2017).

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support – Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Maier-Hein, L. et al. Eds.). Vol. 11045 . 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00889-5_1 (Springer, 2018).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539 (2015).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 9351. 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (Springer, 2015).

Athanasiou, L. Atherosclerotic Plaque Characterization Methods Based on Coronary Imaging (Elsevier, 2017).

Tee, G. Surface area of ellipsoid segment. In Research Report (Department of Mathematics, The University of Auckland, 2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have contributions with respect to the following: Conceptualization, Methodology / Study design, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing original draft, Writing review and editing, Visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De, M., Dutta, S. & Mukherjee, M. Enhanced in-situ monitoring of metal deposition behaviour for pulsed wire arc directed energy deposition using integrated noncoaxial imaging and supervised deep learning framework. Sci Rep 15, 42003 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26001-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26001-4