Abstract

This mixed-methods study examines how participant-identified childhood or youth trauma resurfaces during psychedelic states and how such episodes relate to post-experience trajectories. Including events participants identified as traumatic during psychedelic experiences, and subsequent psychological outcomes, both positive and negative. While psychedelics can facilitate emotional processing of autobiographical material, a minority experience adverse effects or re-traumatization when trauma resurfaces. Phase 1 surveyed 608 individuals who experienced post-psychedelic difficulties lasting beyond acute effects. Those who reported that their post-psychedelic difficulties seemed to be related to early trauma (41.8%) were significantly older, more often female, were more likely to report a prior mental-illness diagnosis, and were more likely to use psychedelics in guided settings compared to those who did not. They also reported significantly more emotional difficulties but fewer perceptual difficulties after the experience. Phase 2 involved semi-structured interviews with 18 purposively selected participants. Reflexive thematic analysis identified four themes describing how trauma surfaced during psychedelic experiences: direct trauma re-experiencing (39% of participants, including some with no prior memory of events), symbolic/somatic re-embodiment (22%), and fragmentation and confusion (50%). A fourth theme captured varied post-experience trajectories, ranging from predominantly positive integration (50%) to mixed effects (28%) to re-traumatization (22%). The study highlights uncertainty around memory veridicality as a source of ongoing distress for some participants. Findings emphasize the critical need for trauma-informed approaches to psychedelic use, stressing appropriate preparation, supportive settings, and robust integration support to maximize therapeutic potential while preventing re-traumatization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The usage of psychedelic substances has increased in recent years across varied contexts, including psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT)1, guided retreats, and self-guided contexts2,3, with many users reporting positive outcomes. However, for some users, especially in the absence of therapeutic support, intense psychedelic experiences may be destabilizing and exacerbate pre-existing insecurities4, and a significant minority experience adverse or even traumatic effects, and negative long-term psychological outcomes5,6,7,8,9,10,11. This is particularly the case in the absence of adequate preparation, or integration frameworks7,11, unsafe or poorly supported settings6,7,8, or individual vulnerability factors such as personality traits or prior trauma12,13,14. Little attention has been paid to cases where psychedelic use appears to induce distressing autobiographical material, including apparent previously inaccessible memories of early life trauma. This paper explores how such experiences unfold, the ambiguity surrounding their meaning and origin, and the role of contextual support in shaping post-experience outcomes.

In DSM-5,15 a traumatic event is defined as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, whether directly, by witnessing, learning of it happening to a close other. While this definition guides clinical research, it excludes many experiences that people themselves describe as traumatic. For this study, we adopt a phenomenological rather than diagnostic definition of trauma: experiences that participants themselves perceived as profoundly threatening, identity-shattering, or emotionally overwhelming, regardless of whether they meet DSM-5 Criterion A. This approach aligns with our focus on subjective meaning-making and lived experience rather than clinical classification. Our use of “trauma” throughout this paper therefore refers to participant-identified adverse autobiographical memories that were self-defined as trauma, which in our sample included childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, attachment disruptions, bereavement, etc. (see Table 4).

Psychedelics may modulate autobiographical memory and emotion through certain neurobiological and psychological mechanisms, but current evidence does not support the classical notion of “unlocking” “repressed material”16. Classic psychedelics act primarily through 5-HT2A receptors and disrupt large-scale brain networks, such as the default mode network, which are implicated in autobiographical processing, emotional regulation, and self-referential processing17,18. These effects appear to reshape rather than release memory content, amplifying the salience, affective tone, and vividness of imagery and autobiographical themes.

In MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, similar processes may be supported by reduced amygdala reactivity and increased connectivity with the hippocampus, potentially enhancing emotional engagement with traumatic memories under conditions of heightened safety and reduced fear19. Controlled studies show that MDMA and classic psychedelics often impair working, semantic, and episodic memory during acute intoxication, with effects increasing dose-dependently20,21,22. While users may feel that psychedelics reveal buried memories, current findings suggest such content is more constructed or imaginatively processed than veridical recollection16.

McGovern and colleagues’ False Insights and Beliefs Under Psychedelics (FIBUS) model proposes that altered serotonergic and dopaminergic signaling may heighten noetic confidence while weakening hippocampal-mediated recall, leading to powerful, but potentially inaccurate, beliefs or memories23. Psychedelics may also open reconsolidation windows24, making memory traces more malleable depending on the emotional or contextual environment18,25.

Emotional mechanisms such as shame and guilt may also play a role in how past events are reevaluated. Mathai et al. found that psilocybin use was frequently associated with shame or guilt about past events, with some users reporting lasting reductions in trait shame, while others showed increases26. Another study found 7% of participants linked such feelings to resurfaced trauma8.

Psychedelics may intensify emotional processing of autobiographical material27, sometimes triggering distressing re-experiencing followed by emotional breakthroughs, interpersonal connectedness, or positive personality shifts21,28,29,30. For instance, individuals who recollected adverse life events during ayahuasca ceremonies showed decreased neuroticism post-ceremony as well as three months later27. Even highly distressing experiences may later be reinterpreted as transformative, especially when supported by narrative reconstruction21,31,32. In a psilocybin trial for anorexia nervosa, two participants initially destabilized by resurfaced trauma later reported long-term symptom reduction33.

In some cases, psychedelic sessions appear to trigger the emergence of previously inaccessible memories of early trauma, including sexual abuse. Although the term “repressed memories” is now considered outdated - a relic of the ”Memory Wars”16,34 - some participants describe recovering events they had no prior memory of. For example, Amy Griffin’s memoir The Tell recounts how she reports recovering memories of childhood sexual abuse during MDMA-assisted therapy35. In one survey, 38% of those who reported a traumatic psychedelic experience recalled childhood sexual abuse post-experience, nearly half without any prior recollection36.

A key question for researchers and therapists is whether psychedelic recollections reflect factual autobiographical memories or not37. Timmerman et al. discuss a case of apparent memory of childhood abuse that was later reinterpreted symbolically during integration37. Such cases suggest that some recollections may be metaphorical images akin to those frequently found in the dreams of PTSD sufferers27,32.

For a minority of users, psychedelics can induce distressing experiences both during the acute phase and long after drug effects subside38. Such extended difficulties, which can last for months or years, can include anxiety, intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, cognitive confusion, derealization, and depersonalization5,6,7,8,9,11,39. Some link extended difficulties to re-experiencing past adverse events during the session8. Argyri et al. identified “becoming conscious of repressed material” as a high-consensus post-psychedelic difficulty (8/28 mentions by psychedelic integration practitioners), often involving childhood-linked memories, somatic cues, or abuse-related content, frequently with paramnesia concerns and flooding or containment problems40.

Dissociation may occur after sudden recollections of trauma during psychedelic experiences41. Reports of fragmentation, depersonalization, and derealization5,39 align with trauma-related dissociation42. Thal et al. found that trauma history, not drug use, was the stronger predictor, suggesting psychedelics may interact with underlying vulnerabilities rather than cause dissociation outright14.

Extended difficulties may occur when resurfaced material is not adequately supported or contained5,8, raising the challenge of how best to support individuals in trauma-related distress after psychedelic experiences. Practitioners emphasize trauma-informed integration, including therapy, grounding techniques, and meaning-making tools40. Both qualitative and quantitative studies highlight the importance of informal resources such as peer support, self-education, meditation, time in nature, and embodied strategies like exercise and breathwork. Participants also note the importance of feeling accepted and validated by others10,43. Narrative processing, central to trauma recovery44, may be either facilitated or hindered by how individuals interpret emotionally intense material. In sum, personalized integration approaches that combine both clinical and informal resources are likely to be optimal.

Aims and research questions

As outlined above, existing research shows that experiences of resurfaced trauma during a psychedelic episode can bring therapeutic breakthroughs or, conversely, lead to disintegration and emotional destabilization42. Given the complexity and variety of outcomes, further research is needed on this topic to understand the conditions under which re-experiencing adverse events can lead to an improvement or decline in emotional well-being. This is particularly important considering the widespread hope that psychedelic medicine may represent a breakthrough intervention for PTSD. While prior research has examined challenging psychedelic experiences, few studies have addressed how the experience of resurfaced childhood trauma relates to long-term difficulties. Fewer still have explored how individuals understand and cope with such experiences. This study uses a two-phase mixed-methods design combining a large-scale survey and in-depth interviews with individuals who reported resurfaced childhood trauma during psychedelic use that contributed to lasting psychological challenges. The research questions that guided this inquiry were:

(1) How do people experience and understand recollections of trauma from their childhood or youth that manifest as part of reports of post-psychedelic difficulties, and what characterizes these across memory, body awareness, emotional intensity, and post-session meaning-making?

(2) What interpretive, relational, or contextual factors appear to shape whether individuals go on to experience therapeutic integration, ongoing distress, re-traumatization, or mixed patterns of these following such experiences?

Together, these questions aim to illuminate both the phenomenological contours of trauma resurfacing during and after psychedelic sessions and the broader psychosocial processes that influence post-experience trajectories of change.

Method

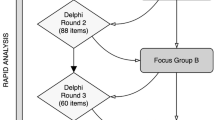

Mixed-methods design

The study employed a sequential mixed-methods design45, consisting of two phases. Phase 1 was an online survey in which participants provided retrospective self-report data about psychedelic experiences and extended difficulties following these experiences. After completing the first phase, individuals were purposively sampled from the Phase 1 sample based on the criterion of having reported in the survey that they perceived a trauma in their childhood or youth to be linked to their experience of post-psychedelic difficulties. In Phase 2, online in-depth interviews were conducted with these participants to explore this further.

Participants

Phase 1

Survey participants were required to have experienced difficulties after the use of a psychedelic in the past that led to functional difficulties that lasted for more than a day after the effects of the drug had concluded. They were also required to be aged 18 or over, and to write English to a proficient or fluent standard. The survey was distributed via an online newsletter, social media channels, student email lists, and a newspaper advertisement. There were no financial incentives for participation. 608 individuals completed the survey. A breakdown of demographic information is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Phase 2

Participants were recruited for interviews if they met the following criteria: (1) They had responded “yes” to the question: “Was there a traumatic experience in your childhood or youth which you think may have played a role in the difficulties that arose during or after the psychedelic experience?” (2) Classic psychedelics had initiated the difficulties they reported, (3) they were living in a country where English is the primary language, and (4) if they had consented to be approached for a follow-up interview. 33 individuals met these criteria and consented to be interviewed. Of these, we were able to arrange and complete interviews with 18 individuals. Of the final sample, 12 were female and 6 were male. The age range was from the early 20s to the late 50s, with a mean of approximately 35. Reported childhood traumas comprised childhood abuses (sexual, physical, and emotional neglect), attachment/relational/abandonment trauma, bereavement-related, and illness-related trauma. Other traumatic experiences not within childhood or youth were also reported as connected to the post-psychedelic difficulties, such as combat-related trauma. Psychedelic substances that elicited the difficulties were ayahuasca (6), psilocybin (10), and LSD (2). In terms of the setting of taking the psychedelic, 9 were in facilitator-guided settings, and 9 were in unguided/informal settings. All participants provided informed consent, and confidentiality was assured; participants could review transcripts and withdraw at any time.

Procedure and data collection

Ethical approval from the University of Greenwich Ethics Board was obtained prior to the commencement of data collection (application ref: 21.5.7.20). Additionally, Bar Ilan University’s IRB approved the second phase of the study. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation; interviewees also consented to audio recording and anonymized transcription. No identifying information is included in this article.

Survey

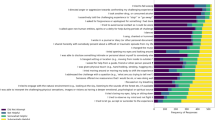

Data was collected anonymously via an online survey delivered on the survey platform Qualtrics, between November 2022 and April 2023. The variables reported in the current study are as follows: (1) Age, (2) Gender, (3) Educational level, (4) Challengingness of the acute psychedelic experience, (5) Setting of experience, (6) Difficulties reported after the experience (emotional, self-perception, cognitive, social, ontological, spiritual, perceptual, other), (7) Range of difficulties reported, (8) Duration of difficulties, (9) Continued use of psychedelics or not, (10) Traumatic experience in childhood or youth perceived that is linked to difficulties, 11. Belief in benefits of psychedelics relative to risk. A full list of survey questions and response scales/options used in the current study is available in Supplementary Materials. Other data and analyses from the survey, including analysis of open-ended response data, are reported in Evans et al. (2023) and Robinson et al. (2024).

Interviews

Participants were selected for an interview on the criterion of reporting in the survey a perceived link between a trauma in childhood or youth and the post-psychedelic difficulties. They completed a semi-structured interview, lasting 60–90 min, with a trained qualitative researcher via a secure video call. The participant shared a narrative of the difficulties they encountered during and after the psychedelic experience reported in the survey, including the setting and substances used, detailed phenomenological descriptions of what they saw and felt (primarily when material that was perceived to be traumatic arose), how they coped during the event, the difficulties they experienced afterwards, and how they processed the experience. Open-ended prompts encouraged depth. The interview guide is available in the Supplementary Materials. Interviewers employed empathetic listening and, when needed, grounding techniques, pausing the interview if a participant became extremely distressed. After each interview, participants were debriefed and provided with resources or referrals for integration support, as appropriate. All interviews were audio-recorded with permission, professionally transcribed verbatim, and anonymized. Transcripts preserved participants’ original wording and emotional tone (with minor filler words removed) to ensure fidelity to their voice while protecting identities.

Quantitative analyses

IBM SPSS v.28 was used to run all statistical tests. The analyses compared 19 dependent variables across two independent groups: those who responded Yes or No to the question about a traumatic experience being perceived as linked to difficulties. For dependent variables measured on a Likert scale or a continuous interval-level scale, t-tests were conducted. For variables measured on a non-interval scale, the Mann-Whitney test was conducted. For variables with categorical response options, Chi-Square analyses were performed. Given the number of tests conducted, the P-value was corrected to p < 0.01 for significance using the Hochberg step-up method46. Parametric assumptions were met for the t-test analyses.

Qualitative analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis47, combined with specific elements of Multiple Case Narrative methodology48. Elements of MCN were incorporated by treating each participant as a distinct case, preserving narrative coherence during within-case analysis before identifying cross-case themes. This allowed us to retain individual meaning structures while systematically comparing experiences across the dataset. This dual analytic approach allowed us to identify case patterns while honoring each person’s unique story. A shared codebook was maintained and iteratively refined through discussion among four analysts. Data immersion was achieved through repeated readings of transcripts. Next, coding was conducted using MAXQDA (VERBI Software, MAX Qualitative Data Analysis, version 24.7.0; https://www.maxqda.com). Coding of each transcript was done line-by-line, assigning codes for both explicit content (e.g., “flashback,” “body froze”) and underlying processes (e.g., “regressed to child-self,” “ego dissolution”). Discrepancies in coding were resolved through consensus in analyst meetings, ensuring that the codes remained grounded in participants’ words and meanings. We then developed themes by clustering related codes and examining conceptual connections across cases. The results below present participant quotes, along with their ID numbers (P1–P18); minor verbal fillers have been removed for readability. To enhance trustworthiness, we employed researcher triangulation, maintained reflexive journals documenting analytical decisions, and conducted member checking with select participants to verify interpretations. Our reporting adheres to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines for comprehensive qualitative research reporting49.

Results

Quantitative results

In terms of responses to the question “Was there a traumatic experience in your childhood or youth which you think may have played a role in the difficulties that arose during or after the psychedelic experience?”, 243 (41.8%) responded Yes, 180 (31.0%) responded No, and 158 (27.2%) responded Unsure. Participants self-identified traumatic experiences without reference to clinical diagnostic criteria, which may include a broader range of adverse experiences than would meet DSM-5 Criterion A for traumatic events. For the quantitative between-groups analysis, those who responded Unsure were excluded to ensure a clear comparison of those with and without the experience of trauma linked to their post-psychedelic difficulties. Table 1 presents the inferential and descriptive statistics from comparing 18 variables across the Yes and No groups, using a series of t-tests, Mann-Whitney tests, and Chi-square tests, depending on the nature of the dependent variable.

The results in Table 1 show that those who experienced a link between an early trauma and their experience of post-psychedelic difficulties, when compared with those who did not, were on average (1) significantly older, (2) had a significantly higher proportion of females, (3) were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with a mental illness prior to the psychedelic experience, (4) were more likely to be taking psychedelics in a guided setting, and (5) be more likely to believe that using psychedelics lead to benefits that outweigh the risk involved. In terms of the post-psychedelic extended difficulties they reported, there were (6) significantly more likely to report emotional difficulties after the psychedelic experience, but (7) significantly less likely to report perceptual difficulties.

Qualitative results

Our analysis addresses two distinct but related dimensions of participants’ experiences. First, we examined the phenomenology of how traumatic material surfaced during psychedelic sessions, identifying three experiential modes: direct re-experiencing, symbolic/somatic re-embodiment, and fragmentation/confusion. Second, we analyzed post-experience trajectories, the varied outcomes following these sessions, which ranged from predominantly positive integration to mixed patterns to re-traumatization. These dimensions are independent: individuals experiencing any phenomenological mode could follow any trajectory, depending on contextual factors such as preparation, support, and meaning-making resources.

Despite the heterogeneity of participants’ backgrounds and psychedelic experiences, clear patterns emerged in how experiences perceived as traumatic were encountered and made sense of during the psychedelic state. All participants described their past trauma coming to conscious awareness during the difficult trip, though the mode of resurfacing varied. Seven participants (~ 39%) described vividly re-living a traumatic event, often with intense sensory and emotional detail. Of these, three participants explicitly stated that the trauma they re-experienced had not been previously recalled in conscious memory prior to the psychedelic session. Four others did not retrieve an explicit autobiographical memory but instead encountered trauma-related content through symbolic imagery, intense emotion, or somatic sensations they interpreted as related to earlier adverse experiences. The experiences of 9 participants were often disjointed or confusing, with fragments of memory or feelings that were hard to piece together. Below, we present the four major themes that encapsulate these variations. These themes, with their prevalence, key characteristics, and representative quotes, are summarized in Table 2. We illustrate each theme with representative interview examples (using participant numbers for attribution).

Trauma-related psychedelic experiences and associated post-experience trajectories

Our analysis also elicited distinct patterns in how childhood trauma surfaces during challenging psychedelic experiences. Despite the diverse backgrounds and substances used by participants, four primary themes emerged: (1) resurfacing and re-experiencing of childhood trauma, (2) symbolic or somatic re-embodiment of trauma, (3) fragmentation and confusion, and (4) post-experience outcomes from therapeutic integration to re-traumatization. Approximately 39% of participants (7/18) reported directly re-experiencing childhood trauma during their psychedelic session, often with vivid sensory recall. As one participant (P5) described: “The ayahuasca, just the entire trip, was like, yeah… your father sexually abused you. It was just like 100%. It put my entire life in context […] Every single thing made sense after that.”

Another participant (P4) described their vivid recall of a childhood trauma: “My mind suddenly had this picture in it of my bedroom door when I was a child, opening, and a figure walking through. And I knew it was my father. And I knew it was him visiting me in the night. And I knew what it meant… It was your… Just the most devastating moment in my life.” Another participant (P11) mentioned how the psychedelic experience uncovered childhood trauma that they were not aware of before: “I lived forty years in my life, thinking I had a great life, with no bad experience and stuff like that. And now I’m just like awakened. And now I have, I contacted this part of myself, which has a traumatic experience when I was a kid, I realized a lot about my mother, issues with my family… So it created a relationship with my trauma.”

Another subset of participants (22%) experienced trauma through bodily sensations or symbolic imagery rather than explicit memories, with one participant (P1) noting: “I felt that that trip really helped like did that for me, in an animal way, like animals in nature, they have a trauma, they shake it off. And they move their body to shake it off and they’re fine. Their nervous system is fine again… I felt like that trip did that for me, shake my body at such a profound level that it was energetically and cellular, fallible, palpable.” Another participant (P7) recalled: “I think there’s a big somatic piece for me with psychedelics, very physical, it’s far less intellectual or cognitive, so there’s a huge piece in the body. I think there’s been, yeah, somatic shifts in my body, perhaps where the trauma has been stored.” Participant 1 shared how their body reacted to the experience:” I was shaking, twitching, convulsions… somatic experiences, I can’t say something helped me manage the sort of violent somatic response that was going on.”

Half of the participants (50%) described fragmentation and confusion during their experience, struggling to make sense of emerging trauma content or questioning the authenticity of recovered memories. One participant (P3) expressed this uncertainty: " Thoughts were muddled, emotions didn’t match the thoughts that they once previously did… Everything was just different. I felt very dissociated. Depersonalised. A lot of derealisation as well towards things from my perspective.” Participate P15 recalld: “I felt totally disconnected from my body, my mind feels thick and stuck, and my emotions, emotions are electrical and many. I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired… I feel lost and forgotten, isolated, overwhelmed with the trauma.” Another participant (P5) remembered: ”I would just say the trauma and psychedelics thing has been just so confusing. There is no clear path, and that really stands out to me, the confusion, the framing of the experience, the nebulous nature, to find something to grab onto, and nobody can tell you what’s true.” And P6 said: ” As the letters and words fell from the sky, I lost the ability to speak. It was a number of hours of things rushing past me very, very quickly in quite a frightening way, and me not being able to really make any sense of what was happening.”

As shown in Table 3, participants’ post-experience trajectories of change fell into three categories: predominantly positive integration (50%), mixed negative/positive change (28%), and predominantly negative or re-traumatization (22%). Those reporting positive trajectories often described profound healing despite initial distress caused by the exposition to the trauma during the psychedelic state, as evidenced by statements such as, “I’m probably a much better person because of it” (P9) or another participant (P5) who said: “I don’t think I would be where I am now if I didn’t have that challenging trip. It set so many things into motion… My whole nervous system kind of had a reset I feel.“, And participant P12, who said: “I look at [the traumatic experience] as being sort of the beginning of me being forced to wake up… A lot of the work I’m doing now is because I’m approaching it differently… the only way I was going to be able to function day to day was just to be dealing with some of this other stuff that had been holding onto for a long time.” Those with mixed trajectories acknowledged benefits alongside ongoing challenges: “Overall, it was a very healing experience. But… not having closure about it was harmful for me and my family” (P3). Participants reporting negative trajectories described symptoms resembling re-traumatization: “I didn’t cope well after it. I had a lot of problems with sleep, and I was having flashbacks” (P7). And participant P9 shared: “The next like five years I’d say… I was extremely dissociated, I would be in constant terror, fear, dread, and despair. I was dissociating always. Whenever I’d see my parents, I would fall into this like a dissociating fear. I would have flashbacks of feeling like my mind was broken, it just felt like it shattered.”

Discussion

Discussion of quantitative findings

The quantitative survey findings provided evidence that individuals who report a link between an early trauma and post-psychedelic extended difficulties, when compared with those who do not, are on average older, more likely to be diagnosed with a mental illness prior to the psychedelic experience, more likely to be taking psychedelics in a guided setting, more likely to believe that using psychedelics lead to benefits that outweigh the risk involved, and have a higher proportion of female. In terms of the age difference between the groups, one possible interpretation is that older participants may be more likely to reflect on earlier life experiences in the context of psychedelic difficulties. While the survey did not ask whether these traumatic events had been previously forgotten, this pattern may still align with developmental theories such as Hollis’s idea of midlife as a period when unconscious material becomes more salient or emotionally charged50. However, further research is needed to determine whether age-related recall dynamics played a role in how trauma was interpreted in these experiences. We also found that participants who linked their post-psychedelic difficulties to early trauma were more likely to be in guided settings for the psychedelic experience. This can be interpreted as those with past trauma having a stronger motivation for safety and containment in their psychedelic work, and possibly an explicit intention to work on post-traumatic symptoms in a guided setting rather than to take the drug recreationally51. Another interpretation in the opposite causal direction is that guided settings may create a therapeutic environment (therapeutic suggestibility) where forgotten material, such as early trauma, is more likely to emerge (or be perceived to emerge) during the psychedelic experience. This aligns with accounts that psychedelics can increase the frequency and felt certainty of insights, whether beneficial or misleading, especially in suggestive contexts23.

The higher proportion of females in the group linking trauma to difficulties could align with previous research that suggests women are more likely to experience early interpersonal trauma (e.g., sexual abuse) and to engage in help-seeking behaviors52. It may also reflect gendered differences in emotional expressivity and trauma disclosure in post-experience narratives53, and possible serotonergic sensitivity due to hormonal factors54,55. Goldner et al. also found that women were more likely to engage in “tend-and-befriend” coping rather than avoidance, which may reflect gendered differences in disclosure and help-seeking, and might partially explain the therapeutic-seeking and openness to guided use56.

A belief in the benefits of psychedelics is higher in the group with recalled trauma. This may stem from having had an experience in healing through catharsis or self-transformation, despite encountering difficulties. It could also reflect a form of post-traumatic growth57, where participants retrospectively frame challenging experiences as meaningful or valuable, even when they involve resurfacing trauma29.

In terms of the post-psychedelic extended difficulties reported, those who re-experienced past trauma were significantly more likely to report emotional difficulties after the psychedelic experience than those who did not, but were less likely to report perceptual difficulties. This may also point to suggest different neural processing - possibly, this pattern might reflect differential engagement of affective vs. sensory systems; however, the present data cannot adjudicate mechanisms (Table 4).

Discussion of qualitative findings

The qualitative analysis supports previous findings that psychedelic experiences have the potential to heal or exacerbate trauma25,37. On the one hand, participants described how they facilitated emotional and somatic breakthroughs58, as has been previously described in research59. On the other side, some participants conveyed that they led to emotional overwhelm and re-traumatization, where the set and setting were problematic and where there was little support for integration and navigating subsequent challenges. These patterns are consistent with emerging models that treat psychedelic memory phenomena as a blend of vivid autobiographical constructions and heightened insight signals, whose clinical impact depends on context and integration16,23.

The themes elicited from the qualitative data capture various experiential features of the perceived link between early trauma and post-psychedelic extended difficulties. Theme 1, reported by 39% of participants, captured the experience of remembering past childhood trauma during the psychedelic experience and the direct emotional implications of this. Participants described how the psychedelic experience revealed what appeared to be traumatic memories (of which some had no prior memory). They discussed how this brought profound emotional challenges and opportunities. This echoes the quantitative finding that emotional difficulties after the psychedelic episode were more frequent in the group reporting past trauma60. The immediate aftermath for one participant (P5) included “a dark night of the soul for literally a year,” demonstrating the potentially destabilizing nature of such revelations. Whether such experiences were a veridical recollection of past events was uncertain, particularly given that a proportion of participants had no prior memory of the event, and this uncertainty was itself anxiety-inducing for some. For example, P3’s case shows this feature of being haunted by uncertainty. This represents prior work on this topic, which mentions that the lack of certainty - “not knowing if it’s real or not” - can become traumatic, leading to ongoing distress long after the session37,61.

Theme 2, symbolic/sensory re-embodiment of trauma (experienced by 22% of participants) captures the bodily, symbolic, and non-literal representation of trauma, which the participants interpreted as meaningfully linking to past adverse events. These physical manifestations can be construed as indirect representations of forgotten or suppressed emotions that seek expression62. The therapeutic value of such experiences may lie in their ability to allow emotional processing without explicit recall of traumatic events27. These experiences underscore psychedelics’ capacity to engage trauma on a non-verbal level - effectively allowing a person to work through trauma feelings and responses without re-experiencing the original event. However, their indirect nature requires careful professional post-session support and integration to help facilitate healing. The way bodily sensations are framed and interpreted during integration might shape how individuals understand and derive meaning from these experiences, underscoring the importance of skilled therapeutic guidance in this process.

Theme 3: fragmentation and confusion were experienced by 50% of our participants. It represents reports of how the psychedelic state can sometimes overwhelm an ability to cope, leading to a feeling of disintegration that may itself echo the feeling of being traumatized. P3 described profound disconnection with muddled thoughts and emotions that no longer matched, accompanied by feelings of dissociation, depersonalization, and derealization. P6 experienced overwhelming cognitive disruption, losing the ability to speak as imagery rushed past in a frightening way that defied comprehension. Beyond immediate disorientation, P5 articulated confusion extending to the entire therapeutic process itself, describing the lack of clear pathways and the nebulous, difficult-to-grasp nature of attempting to work with trauma through psychedelics. For example, P15’s experience suggests that even when participants know something important was processed through intense physical release, the nonverbal and strange nature of the experience can make it difficult to explain or integrate. Such cases may require extensive reflection or therapy afterward to construct meaning from the experience.

Theme 4 captured the varied post-experience trajectories from therapeutic integration to re-traumatization. The divergent trajectories reported (as summarized in Table 2) suggest that preparation, context, and support play crucial roles in determining whether psychedelic encounters with trauma lead to healing or further harm. These outcomes may also be shaped by factors such as attachment history63, cultural framing64, and the degree of interpersonal or therapeutic support available during or after the experience65. Generally, participants with positive outcomes (50%) had been prepared within a therapeutic framework or sought integration afterward, while those with adverse outcomes (22%) often lacked sufficient support. The meaning ascribed to the experience also appears critical. Even when the trip was extremely challenging, those who found meaning (like P9, who decided the experience revealed his calling to help others) tended to fare better than those who viewed it as “just bad” or meaningless suffering.

The findings suggest that when challenging psychedelic experiences involve the reactivation or recollection of past trauma, careful therapeutic management is essential to minimize harms and maximize potential benefits, if any. With appropriate preparation, setting, and follow-up integration, they can serve as opportunities for deep healing, allowing individuals to confront past traumatic experiences in a way that promotes a new approach to and relationship with the traumatic experience27. Without adequate support, such experiences risk re-traumatization25,36. Participants who experienced trips alone without any guide or subsequent therapy show how a lack of support can leave someone to cope with the fallout on their own, potentially worsening trauma symptoms. Conversely, those who actively engaged in integration work through psychotherapy, journaling, meditation, support groups, or deep personal reflection are more likely to report that they transform their challenging experiences into healing10.

Limitations and future directions

Several notable limitations accompany this study. First, while the survey phase had a large dataset, the self-reported nature of past experiences and trauma experiences may lead to recall bias, social desirability bias, or underreporting, especially given the sensitive topic. Online administration further limits control over participant understanding and engagement. The qualitative phase allowed for richer exploration of trauma’s impacts but included only a small, non-random subset of the survey sample who were purposively sampled for reporting a link between childhood trauma and extended post-psychedelic difficulties. This targeted sampling may have introduced selection bias, as those who volunteered for interviews may have differed systematically from those who did not. For example, they might have met the same criteria, such as being more comfortable discussing trauma or having fewer extreme experiences. As such, the findings from interviews may not be representative of the broader population surveyed. Moreover, conducting interviews online can limit rapport and nonverbal communication, both of which are crucial in sensitive discussions. Theme prevalences reported for the 18 interviews are descriptive of this purposively sampled subset. They should not be generalized to the Phase 1 cohort or wider populations. Finally, both phases rely on internet access and digital literacy, which may potentially exclude marginalized populations and introduce sample bias. Additionally, “trauma” in this study was self-defined rather than clinically assessed, reflecting participants’ subjective interpretations rather than formal diagnostic criteria. Overall, while the mixed-methods design enriches the understanding of trauma, these methodological limitations must be carefully addressed.

Future research in this area will benefit from longitudinal studies with existing cohorts, such as the Dunedin study66. This would allow for objective information about adverse childhood experiences that were gathered at the time to be cross-checked against reports of such experiences from those working with psychedelics. Another important step will be to gain the views of experts and practitioners working in the field of psychedelic integration to collate their knowledge of best practice when working with individuals processing perceived recollections of, or emotions associated with, past trauma.

The study focused on people who believed an earlier experience of trauma led to post-psychedelic difficulties. It did not ask how many of these earlier experiences of trauma were recalled for the first time during the psychedelic experience. Nor did it focus directly on the question: ‘How sure are you that this earlier experience of trauma really happened?’ Although some interviewees voluntarily shared their feelings on the topic, expressing a range of views from very certain to not-so-certain. We did not seek external corroboration of recalled events; findings concern subjective recall and meaning-making rather than verification of historical accuracy. The degree of certainty regarding the truth of the memory may be related to the degree of catharsis experienced by the person, although this requires further exploration in future studies. Certainty is not the same as truth - there remains the question of whether or how often recovered memories of early trauma during psychedelic experiences are genuine and veridical, when they are hallucinations, how a person (and their therapist) can discriminate between genuine memory and hallucination, and how to live with the possibility of not knowing for sure. There is also the question, worthy of future investigation, of whether memories of early trauma could be suggested to or implanted in individuals while they are in suggestible psychedelic states, by guides or therapists overly invested in the ‘trauma catharsis’ theory of psychedelic healing or more broadly the ‘trauma culture’.

In summary, this study points towards the central importance of developing a trauma-informed and trauma-literate approach to working with psychedelics that can be applied across clinical and non-clinical settings. The benefits of this will be threefold. Firstly, it will allow for evidence-based support for the therapeutic and existential challenges that emerge for individuals who are re-experiencing or processing what appear to be memories of past trauma. Secondly, this will provide a foundation of support for those with PTSD, such as army veterans, who seek therapeutic help through psychedelics27. Thirdly, a trauma-informed approach to psychedelic work will help to mitigate against the chance that the psychedelic experience itself is traumatic25. Our qualitative findings suggest that the trajectories of change following the experience are influenced by the context and care surrounding it. A trauma-informed psychedelic culture will maximize the conditions for integration and support, so that encounters with past events (or what may be subjectively construed as such) can be transformed into a step toward wholeness rather than a re-wounding.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of trauma-related narratives and the need to protect participant confidentiality. De-identified excerpts or summary data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and pending ethical approval.

References

Mitchell, J. M. & Anderson, B. T. Psychedelic therapies reconsidered: compounds, clinical indications, and cautious optimism. Neuropsychopharmacol 49, 96–103 (2024).

Basedow, L. A. & Kuitunen-Paul, S. Motives for the use of serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 41, 1391–1403 (2022).

Kopra, E. I. et al. Investigation of self-treatment with lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin mushrooms: findings from the global drug survey 2020. J. Psychopharmacol. 37, 733–748 (2023).

Cherniak, A. D., Mikulincer, M., Gruneau Brulin, J. & Granqvist, P. Perceived attachment history predicts psychedelic experiences: A naturalistic study. JPS 8, 82–91 (2024).

Bremler, R., Katati, N., Shergill, P. & Erritzoe, D. Carhart-Harris, R. L. Case analysis of long-term negative psychological responses to psychedelics. Sci. Rep. 13, 15998 (2023).

Bouso, J. C. et al. Adverse effects of ayahuasca: results from the global Ayahuasca survey. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2, e0000438 (2022).

Carbonaro, T. M. et al. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1268–1278 (2016).

Evans, J. et al. Extended difficulties following the use of psychedelic drugs: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE. 18, e0293349 (2023).

Kvam, T. M. et al. Epidemiology of classic psychedelic substances: results from a Norwegian internet convenience sample. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1287196 (2023).

Robinson, O. C., Evans, J., McAlpine, R. G., Argyri, E. K. & Luke, D. An investigation into the varieties of extended difficulties following psychedelic drug use: Duration, severity and helpful coping strategies. JPS 9, 117–125 (2025).

Simonsson, O., Hendricks, P. S., Chambers, R., Osika, W. & Goldberg, S. B. Prevalence and associations of challenging, difficult or distressing experiences using classic psychedelics. J. Affect. Disord. 326, 105–110 (2023).

Studerus, E., Gamma, A., Kometer, M. & Vollenweider, F. X. Prediction of psilocybin response in healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE. 7, e30800 (2012).

Haijen, E. C. H. M. et al. Predicting responses to psychedelics: A prospective study. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 897 (2018).

Thal, S. B., Daniels, J. K. & Jungaberle, H. The link between childhood trauma and dissociation in frequent users of classic psychedelics and dissociatives. J. Subst. Use. 24, 524–531 (2019).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (2013).

Kangaslampi, S. & Lietz, M. Psychedelics and autobiographical memory – six open questions. Psychopharmacology 242, 2341–2348 (2025).

Carhart-Harris, R. L. & Friston, K. J. REBUS and the anarchic brain: toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 71, 316–344 (2019).

Kéri, S. Trauma and remembering: from neuronal circuits to molecules. Life 12, 1707 (2022).

Feduccia, A. A. & Mithoefer, M. C. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: are memory reconsolidation and fear extinction underlying mechanisms? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 84, 221–228 (2018).

Doss, M. K., Weafer, J., Gallo, D. A. & De Wit H. MDMA impairs both the encoding and retrieval of emotional recollections. Neuropsychopharmacol 43, 791–800 (2018).

Healy, C. J. et al. Acute subjective effects of psychedelics in naturalistic group settings prospectively predict longitudinal improvements in trauma symptoms, trait shame, and connectedness among adults with childhood maltreatment histories. Preprint at. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3rbxe (2024).

Doss, M. K. et al. Unique Effects of Sedatives, Dissociatives, Psychedelics, Stimulants, and Cannabinoids on Episodic Memory: A Review and Reanalysis of Acute Drug Effects on Recollection, Familiarity, and Metamemory.

McGovern, H. T. et al. An integrated theory of false insights and beliefs under psychedelics. Commun. Psychol. 2, 69 (2024).

Nader, K. & Hardt, O. A single standard for memory: the case for reconsolidation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 224–234 (2009).

Calder, A. E., Diehl, V. J. & Hasler, G. Traumatic psychedelic experiences. in Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2025_579. (2025).

Mathai, D. S. et al. Shame, guilt and psychedelic experience: results from a Prospective, longitudinal survey of Real-World psilocybin use. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2025.2461997 (2025).

Weiss, B., Wingert, A., Erritzoe, D. & Campbell, W. K. Prevalence and therapeutic impact of adverse life event reexperiencing under ceremonial Ayahuasca. Sci. Rep. 13, 9438 (2023).

Barrett, F. S., Bradstreet, M. P., Leoutsakos, J. M. S., Johnson, M. W. & Griffiths, R. R. The challenging experience questionnaire: characterization of challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1279–1295 (2016).

Cassidy, K., Healy, C., Henje, E. & D’Andrea, W. Childhood trauma, challenging experiences, and posttraumatic growth in Ayahuasca use. Drug Sci. Policy Law. 10, 20503245241238316 (2024).

Healy, C. J., Lee, K. A. & D’Andrea, W. Using psychedelics with therapeutic intent is associated with lower shame and complex trauma symptoms in adults with histories of child maltreatment. Chronic Stress. 5, 24705470211029881 (2021).

Gashi, L., Sandberg, S. & Pedersen, W. Making bad trips good: how users of psychedelics narratively transform challenging trips into valuable experiences. Int. J. Drug Policy. 87, 102997 (2021).

Rose, J. R. Memory, trauma, and self: remembering and recovering from sexual abuse in psychedelic-assisted therapy. JPS https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2024.00363 (2024).

Peck, S. K. et al. Therapeutic emergence of dissociated traumatic memories during psilocybin treatment for anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 13, 89 (2025).

Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L. & Patihis, L. What science tells Us about false and repressed memories. Memory 30, 16–21 (2022).

Griffin, A. The Tell: A Memoir (Dial, 2025).

Evens, R. PTSD as a Potential Post-Psychedelic Complication? YouTube, Breaking Convention, 13 August 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMfvtZp7COc

Timmermann, C., Watts, R. & Dupuis, D. Towards psychedelic apprenticeship: developing a gentle touch for the mediation and validation of psychedelic-induced insights and revelations. Transcult Psychiatry. 59, 691–704 (2022).

Wood, M. J., McAlpine, R. G. & Kamboj, S. K. Strategies for resolving challenging psychedelic experiences: insights from a mixed-methods study. Sci. Rep. 14, 28817 (2024).

Argyri, E. K. et al. Navigating Groundlessness: An interview study on dealing with ontological shock and existential distress following psychedelic experiences. PLoS One e0322501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0322501 (2025).

Argyri, E. K. et al. Practitioner perspectives on extended difficulties and optimal support strategies following psychedelic experiences: A qualitative analysis. Preprint at. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6303856/v1 (2025).

Nijenhuis, E., Van Der Hart, O. & Steele, K. Trauma-related structural dissociation of the personality. Act. Nerv. Super. 52, 1–23 (2010).

Elfrink, S. & Bergin, L. Psychedelic iatrogenic structural dissociation: an exploratory hypothesis on dissociative risks in psychedelic use. Front. Psychol. 16, 1528253 (2025).

Robinson, O. C. et al. Coming back together: a qualitative survey study of coping and support strategies used by people to Cope with extended difficulties after the use of psychedelic drugs. Front. Psychol. 15, 1369715 (2024).

Kaminer, D. Healing processes in trauma narratives: A review. South. Afr. J. Psychol. 36, 481–499 (2006).

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (Sage, 2017).

Hochberg, Y. A sharper bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75, 800–802 (1988).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Shkedi, A. Multiple Case Narrative: A Qualitative Approach To Studying Multiple Populations (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2005).

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 19, 349–357 (2007).

Hollis, J. The Middle Passage: from Misery To Meaning in Midlife (Inner City Books, 1993).

Litt, L., Cohen, L. R. & Hien, D. Seeking safety: A present-focused integrated treatment for PTSD and substance use disorders. In: Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use Disorders: a Comprehensive Clinical Handbook 183–207 (Routledge, New York, NY, (2019).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 8, 1353383 (2017).

Olff, M., Langeland, W., Draijer, N. & Gersons, B. P. R. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Bull. 133, 183–204 (2007).

Suazo, N. C., Reyes, M. E., Contractor, A. A., Thomas, E. D. & Weiss, N. H. Exploring the moderating role of gender in the relation between emotional expressivity and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity among black trauma-exposed college students at a historically black university. J. Clin. Psychol. 78, 343–356 (2022).

Willcocks, A. Gender differences in attitudes towards trauma/abuse disclosure. Plymouth Student Sci. 14, 669–691 (2021).

Goldner, L., Lev-Wiesel, R., & Simon, G. Revenge fantasies after experiencing traumatic events: Sex differences. Front. Psychol. 10, 431159 (2019).

Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. Target article: ‘Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence’. Psychol. Inq. 15, 1–18 (2004).

Sloshower, J. et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using acceptance and commitment therapy as a therapeutic frame. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 15, 12–19 (2020).

Roseman, L. et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the emotional breakthrough inventory. J. Psychopharmacol. 33, 1076–1087 (2019).

Brewin, C. R. Episodic memory, perceptual memory, and their interaction: foundations for a theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Bull. 140, 69–97 (2014).

Brewin, C. R. Re-experiencing traumatic events in PTSD: new avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology. 6, 27180 (2015).

Van der Kolk, B. A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Penguin Books, 2015).

Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M. & Bretherton, I. The origins of attachment theory. Dev. Psychol. 28 (5), 759–775 (1992).

Hartogsohn, I. Constructing drug effects: A history of set and setting. Drug Sci. Policy Law. 3, 2050324516683325 (2017).

Cassidy, E. K., Dupuis, D., Timmermann, C. & Granqvist, P. Psychedelics, attachment, and enculturation dynamics: prospects and challenges. J. Psychedelic Stud. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2025.00459 (2025).

The Dunedin Study - Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health. & Development Research Unit. (2025). https://dunedinstudy.otago.ac.nz/

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to all the individuals who participated in this study. We thank the survey respondents for sharing their experiences and insights, and especially the interview participants who courageously recounted complex and often painful journeys. Their openness and honesty made this research possible. We also acknowledge the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project (CPEP) for its foundational support and the broader psychedelic research community for its ongoing commitment to safety, integrity, and inquiry.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project (CPEP), a broader initiative supported by the William G. Nash Foundation and the Sarlo Family. However, this specific study did not receive any direct funding from these or other sources. The funders had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GS: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing - Review & Editing; Visualization; Project Administration. NT: Data Curation; Investigation, Review & Editing. MS: Writing, Review & Editing. JE: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing – Review & Editing. Project Administration. OR: Supervision; Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, G., Tadmor, N., Skragge, M. et al. Recalled childhood trauma and post-psychedelic trajectories of change in a mixed-methods study. Sci Rep 15, 42852 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26198-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26198-4