Abstract

Tin sulfide (SnS) nanoparticles were synthesized by a co-precipitation method and combined with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to form an SnS-CNT nanocomposite with enhanced properties. Structural and morphological analyses confirmed successful heterostructure formation: XRD verified the crystalline phases, FE-SEM revealed uniform distribution, and HRTEM showed SnS nanoparticles with an average size of ~ 50 nm. UV-Vis and Raman spectroscopy further supported the electronic and vibrational features of the composite. The material exhibited dual functionality. Under visible-light irradiation, it achieved 96.97% degradation of methylene blue (MB) and 97.77% degradation of ciprofloxacin (CIP), facilitated by efficient charge separation and reactive oxygen species (•OH, •O2−) generation. As a supercapacitor electrode, the composite delivered a specific capacitance of 1792 F g− 1 at 0.5 A g− 1, with > 80% retention after 5000 cycles. The enhanced performance is attributed to the synergistic role of CNTs as conductive scaffolds and SnS as active redox and light-absorbing sites. These results demonstrate the multifunctional potential of SnS–CNT nanocomposites for environmental and energy applications. The findings provide fundamental insights into heterostructure design principles and pave the way for developing next-generation hybrid materials for sustainable technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing multifunctional materials with high-efficiency photocatalysis and electrochemical energy storage represents a promising avenue for tackling global energy and environmental challenges. Photocatalytic presents an intriguing method for energy conversation and environmental cleanup, owing to its prominent characteristics1. Dyes are indispensable in numerous sectors of the dyeing and textile fields. Among them, over 100,000 synthetic dyes, readily accessible commercially, stand out as the most commonly employed option2. Photocatalysis utilizing visible light has emerged as a sustainable approach for environmental remediation, as it effectively harnesses a major portion of the solar spectrum. Upon absorbing visible photons, semiconductor catalysts generate electron-hole pairs that initiate redox reactions, leading to the formation of reactive species3. These active species play a crucial role in degrading persistent organic pollutants, making visible-light-driven photocatalysis a promising green technology. Azo dyes represent the primary category of synthetic organic dyes utilized within the textile sector, thus constituting prevalent industrial pollutants. Their significant production volume results in their release into the environment during manufacturing processes4. Further, in recent years, the advancement of electrochemical systems for energy storage and conversion has garnered significant interest from researchers and engineers5. This growing attention is driven by the urgent need to address critical challenges, including the depletion of fossil fuel resources, the escalating cost of energy, and the pressing concerns of environmental pollution6. As the global demand for sustainable and efficient energy solutions continues to rise, scientists are actively exploring innovative approaches to enhance the performance, durability, and scalability of these electrochemical technologies.

Particularly, in recent times the manipulation of semiconductor chalcogenides at the nano-structural level has garnered attention, primarily due to the capacity to adjust dielectric, electric, and optical properties through meticulous control of shape and dimension. These nanostructures offer potential in a range of applications, including photonics, optoelectronics, and vacuum micro/nano-electronic devices7. Among the array of chalcogenides, tin sulfide (SnS) stands out as a direct narrow band gap semiconductor belonging to the IV-VI group (with an energy gap of approximately 1.30 eV at 300 K)8. Notably, it demonstrates both p-type and n-type conduction9. Structurally, SnS typically adopts an orthorhombic configuration characterized by double layers of closely bonded SN-S atoms, featuring weak intralayer bonding reminiscent of van der Waals interactions10,11,12.

Various research groups have reported the effect of the SnS nanoparticles with metal oxide on photocatalytic degradation efficiency. Nengzi et al.13 present the fabrication of a SnS-decorated TiO₂ nanorods/nanosheets (NRs/NSs) photoelectrode via hydrothermal and SILAR methods. This heterojunction acts as an efficient photoactivator for peroxymonosulfate (PMS), enabling enhanced degradation of various organic pollutants under visible light. Characterization confirmed successful SnS integration, improving charge separation, light absorption, and photocatalytic activity. The SnS/TiO₂ system exhibited strong reusability and stability, with degradation efficiencies above 96% for dyes and pharmaceuticals. Azeez et al.14 investigate the role of surface charge in enhancing the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using titania nanoparticles (TiO₂ NPs). The TiO₂ NPs were synthesized under varying pH conditions to tailor their surface charge and improve electrostatic interaction with the dye. The photocatalyst prepared at pH 10 showed the highest degradation efficiency (97%) and fastest rate (0.018 min− 1). Malekkiani et al.15 This study presents a novel ternary nanocomposite (MWCNTs/ZnO/Chitosan) with enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial performance. The nanocomposite effectively degraded 98.76% of methylene blue within 20 min under UV light. Its high surface area, reduced bandgap, and improved charge separation contributed to superior photocatalytic efficiency. Antibacterial tests confirmed activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

On the other hand, tin sulfide (SnS) has recently attracted considerable attention as a promising electrode material for supercapacitors, owing to its unique layered crystal structure and suitable optical bandgap16,17. These features facilitate efficient charge transport and provide a high surface area for ion interaction. Despite its potential, research on SnS-based materials for supercapacitor applications remains relatively limited, with only a few studies reported to date.

Dar et al. (2021) reported that SnS nanoparticles synthesized using ethanol (SnS-e) exhibited enhanced supercapacitor performance, with a specific capacitance of 284 F/g and an energy density of 216 Wh/kg at a current density of 5 A/g. These findings underscore the significant influence of solvent selection on optimizing the electrochemical properties of SnS for energy storage and photovoltaic applications18. Chauhan et al. demonstrated that SnS nanorods, without the use of binders or conductive fillers, delivered improved supercapacitor performance in a two-electrode setup with 2 M Na₂SO₄. The nanorods achieved a specific capacitance of 70 F/g, an energy density of 1.49 Wh/kg, and a power density of 248.33 W/kg, nearly twice that of SnS-carbon composites, indicating their strong potential for energy storage devices19.

Researcher have been captivated by carbon nanotubes (CNTs) due to their remarkable geometric configurations and extraordinary properties, setting them apart from other carbon nanomaterials. Both experimental and theoretical investigation have showed the remarkable mechanical attributes of carbon nanotubes (both single-walled and multi-walled), showcasing their exceptional characteristics, lightweight nature (~ 2 g/cm3), superior thermal properties, excellent electrical conductivity, high melting point, low density (ranging from 1.2 to 2.6 g/cc), expansive surface area (~ 1000 m2/g), outstanding hydrogen storage capabilities, noteworthy biological properties, heightened resistance to corrosion, and distinctive optical properties20 and possess strong mechanical stability and offer a substantial specific surface area, making them suitable as a catalytic support21.

When SnS nanoparticles are slightly attached to the surface of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), there may be minimal volume changes during the process of sodiation/desodiation, which is crucial for reducing structural degradation22. Moreover, unlike activated carbons and metal oxide particles commonly found in the market, CNT films can be conveniently assembled independently, thereby mitigating the adverse impacts associated with binders and polymers typically present in energy storage devices22. Overall, SnS/CNT composites have the potential to be highly efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of organic pollutants, offering advantages such as enhanced light absorption, improved charge separation, synergistic effect, mechanical stability, and tuned properties23.

Experimental procedure

Chemical details, apparatus, cleaning procedures, and characterization methods are provided in the Supporting Information.

Experiment procedure of SnS and CNT-SnS nanocomposites

The chemical co-precipitation technique is utilized for synthesizing SnS and SnS-CNT nanocomposites. In a standard procedure, 1 g of PVP is dissolved in 35 mL of deionized (DI) water, while a tin precursor (0.025 M) is separately dissolved in 80 mL of DI water. The PVP solution is then combined with the tin chloride solution, and the mixture is stirred vigorously for 45 min at 90 °C. Subsequently, 50 mL of a 1 M Na₂S solution is added to the mixture, which is stirred for an additional two hours. The resulting SnS precipitate is collected, thoroughly washed with ethanol and DI water to remove impurities, and dried in a high-vacuum oven at 120 °C for three hours. For the preparation of CNT-SnS nanocomposites, CNTs are first oxidized by immersing them in a nitric acid and water solution (1:1 volume ratio) overnight. Afterward, the oxidized CNTs are washed extensively with DI water to ensure the removal of residual acid. In the subsequent nanocomposite preparation, 250 mg of the treated CNT powder is used following the same reaction conditions. The synthesis of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite via the co-precipitation method is depicted in Figure S1. The maximum yield obtained for SnS nanoparticles under the present synthesis conditions was 74.6%. The synthesized SnS and CNT-SnS nanocomposites are evaluated for their photocatalytic efficiency in dye degradation applications.

Photocatalytic degradation, electrode fabrication, and electrochemical measurements

The photocatalytic degradation performance of the synthesized samples was evaluated by monitoring the degradation of Ciprofloxacin (CIP) and Methylene Blue (MB) under visible light irradiation. Details regarding the experimental setup, pollutant concentration, and catalyst loading are provided in the Supporting Information.

Similarly, the electrochemical properties of the synthesized SnS and CNT-SnS nanocomposite were investigated using a three-electrode system and an SP-300 potentiostat (BioLogic Science Instruments, France). Cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were performed in a 3 M KOH electrolyte to assess the electrochemical performance. The electrode fabrication procedure and detailed experimental setup are also included in the Supporting Information.

Results and discussion

Phase identification analysis

The crystal structure of the prepared samples is determined by an XRD diffractometer. The diffraction peaks of (110), (120), (021), (101), (111), (040), (131), (210), (141), (002), (211), (112), (042), (212) and (251) crystallographic planes fitting to the orthorhombic, for pure SnS nanoparticle, as depicted in Fig. 1(a) and the peaks clearly matched with JCPDS card: 39–0354, confirming the single-phase formation24,25. Further, the CNT-SnS composite’s XRD analysis confirms the incorporation of SnS into the CNT framework, as confirmed by Fig. 1(a)26. The characteristic peaks of CNT-SnS align well with standard (JCPDS card: 39–0354) data, confirming the presence of a crystalline SnS phase. The peaks attributed to CNTs appear broader and less distinct, which can be associated with the coexistence of crystalline and amorphous carbon phases. A slight variation in peak intensity and position is noticed upon CNT addition, which is likely due to crystallite size effects, lattice strain, and interfacial interactions between SnS and CNTs. It is important to note that while XRD reflects structural modifications, it does not alone provide direct evidence of CNT incorporation. Therefore, the observed peak changes are considered as supportive indications of interaction between CNTs and SnS rather than conclusive proof. Such interactions are expected to enhance the structural stability and electrical conductivity of the composite, making it promising for applications in electronic devices, photocatalysis, and energy storage.

Raman spectrum

The Raman spectrum of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite (Fig. 1(b)) provides critical insights into the vibrational characteristics and interfacial interactions of the hybrid material. The Raman spectra of the synthesized materials were deconvoluted to better resolve the overlapping peaks and understand the vibrational features. For pristine SnS, characteristic Raman modes were observed around ~ 100–200 cm− 1 and ~ 220–3000 cm− 1, which can be assigned to the Ag and B2g vibrational modes of the orthorhombic SnS lattice, respectively. These peaks correspond to the in-plane and out-of-plane vibrations of Sn and S atoms24. The CNT matrix exhibits characteristic vibrational modes at 1352 cm⁻¹ (D-band, disorder-induced mode) and 1583 cm⁻¹ (G-band, graphitic E2g mode) with an ID/IG ratio of 0.753 ± 0.03. This significant enhancement in defect density suggests that covalent functionalization through S-C bond formation at the CNT-SnS interface, creation of additional charge transport pathways, and improved interfacial charge transfer efficiency. The shift and broadening of SnS modes in the composite suggest strong coupling between CNTs and the semiconductor lattice, which may facilitate improved charge separation. Overall, the deconvoluted Raman spectra support the successful formation of CNT-SnS nanocomposites with synergistic structural and electronic interactions.

Optical properties

The optical properties make UV-Vis spectroscopy a valuable tool for studying its band gap and absorption characteristics of SnS and CNT-SnS, as shown in Fig. 1(c). The SnS typically exhibits a strong absorption in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) region. The SnS has a direct band gap of around ~ 2.2 eV and strong absorption in the visible region (~ 400–800 nm)27. The CNT-SnS shows a strong absorption peak around 200–300 nm, which corresponds to the π-π* electronic transitions in the sp² hybridized carbon framework. CNTs generally show broad and weak absorption in the UV-Vis-NIR spectrum rather than sharp peaks. Therefore, the UV-Vis result of CNT-SnS showed a wide range of absorption spectra. The CNT-SnS has a band gap of around ~ 1.8 eV, and the band gap can be estimated using a Tauc plot and shown in Fig. 1(d). A shift in the absorption edge or changes in peak intensity suggest electronic interactions between CNTs and SnS, which could enhance the material’s performance, making it favourable for energy storage and photocatalysis applications.

FE-SEM analysis

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) analysis of the CNT-SnS composite provides valuable insights into its morphology and structural characteristics. Figure 2(a-c) reveals a distinct morphological structure characteristic of tin sulfide. The images show well-defined SnS nanoparticles with the shapes of nanosheets and cubes28,29. The surface texture and particle distribution suggest good crystallinity and controlled growth of SnS. Figure 2(d-f) reveals a well-integrated structure, where SnS nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed over the CNT network30. The surface morphology analysis revealed that the majority of the carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were embedded within the agglomerated tin sulfide (SnS) particles, making them less visibly distinct. However, the incorporation of CNTs induced a significant transformation in the morphology of SnS, converting its mixed nanosheet and cubic structures into a more uniform spherical shape.

This morphological evolution highlights the role of CNTs in modulating the growth and assembly of SnS particles, leading to a more homogeneous and structurally integrated nanocomposite. Such morphological uniformity is critical for enhancing the material’s electrochemical and photocatalytic properties, as it promotes better interfacial interactions and efficient charge transfer pathways. Additionally, the porous and interconnected structure of the composite facilitates efficient charge transport and mechanical stability. The porous structure morphology suggests that the CNT-SnS composite is well-suited for applications in energy storage and photocatalysis31,32.

The elemental composition of the synthesized SnS/CNT nanocomposite was confirmed through energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy, illustrated in Figure S233. The spectrum exhibited prominent peaks of Sn, S, and C, validating the successful anchoring of SnS nanoparticles onto the CNT framework. In addition, minor signals corresponding to oxygen (O) and chlorine (Cl) were observed. The presence of O may be attributed to surface oxidation of SnS nanoparticles or adsorbed oxygen-containing species, while Cl signals are most likely derived from the precursor salts used during synthesis. Importantly, no additional peaks related to foreign impurities were detected, indicating the high purity of the prepared nanocomposite. The near-stoichiometric ratio of Sn and S further supports the formation of the SnS phase, while the presence of CNT ensures the conductive backbone for efficient charge transfer.

HRTEM analysis

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) analysis was conducted to examine the microstructure and determine the particle size distribution of the as-prepared CNT-SnS nanocomposites (NCs). Figure 2(g-k) reveals a uniform dispersion of SnS nanoparticles over the CNT framework, along with the crystalline nature of the composite. The HR-TEM images confirm the successful integration of SnS nanocrystals onto the CNT surface, as evidenced by the distinct lattice fringes with an interplanar spacing of 0.32 nm, corresponding to the (111) plane of SnS (Fig. 2j-k). The average crystallite size of the synthesized SnS nanoparticles was estimated to be ~ 50 nm, which lies within the typical size range, and the obtained size indicates well-defined nanostructures with sufficient surface area, making them suitable for photocatalytic and energy storage applications. The CNTs provide a 3D conductive network with SnS, facilitating rapid electron transport and reducing charge-transfer resistance. The average thickness of the synthesized MWCNTs was measured from the HRTEM micrographs and was found to be 12.24 nm. This value corresponds to the outer diameter of the nanotubes, which is in the range commonly reported for multi-walled carbon nanotubes. the measured thickness suggests that the MWCNTs consist of approximately 30–32 concentric graphene walls. Such a diameter range indicates well-formed multi-walled structures, consistent with previous reports in the literature, where MWCNTs generally exhibit diameters between 10 and 30 nm34,35. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, shown in Fig. 2(l), further corroborates the crystalline structure of the nanocomposite, displaying well-defined diffraction spots and rings that align with the standard crystallographic planes of SnS. The measured interplanar spacings, highlighted in yellow in the TEM images, are consistent with the JCPDS reference data for SnS, confirming the well-ordered phase of the material. This uniform dispersion and crystalline alignment of SnS on the CNT surface enhance the interfacial interactions and charge transfer efficiency, which are critical for optimizing the material’s performance in photocatalytic and supercapacitor applications. These structural insights underscore the potential of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite as a high-performance material for energy storage and environmental remediation.

Photocatalytic analysis

The carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are incorporated with low-bandgap tin sulfide (SnS) nanoparticles in photocatalytic studies due to their excellent electrical conductivity and high surface area, which promote efficient charge separation and transport. SnS, with its narrow bandgap, effectively absorbs visible light to generate electron–hole pairs, while CNTs act as electron acceptors and conductive pathways, suppressing recombination and enabling rapid electron migration. Moreover, CNTs facilitate dye adsorption through π–π interactions, ensuring greater contact between pollutant molecules and active SnS sites. This synergistic combination of strong light absorption by SnS with the superior conductivity and adsorption capacity of CNTs leads to enhanced photocatalytic efficiency, improved stability, and accelerated degradation kinetics of organic pollutants. The photocatalytic performance of the synthesized catalysts (SnS and CNT-SnS) was evaluated by assessing their ability to degrade organic pollutants under visible light irradiation. Key factors influencing photocatalytic activity, such as surface area, visible light absorption, and the synergistic effects of composite materials, were thoroughly investigated. Figure 3(a-b) presents the UV-visible absorption spectra of ciprofloxacin (CIP) solutions treated with the catalysts over a period of 150 min. A gradual reduction in the absorption peaks was observed, indicating the effective degradation of CIP. The degradation efficiencies for SnS and CNT-SnS nanocomposites (NCs) were calculated to be 87.89% and 97.77%, respectively, highlighting the superior performance of the CNT-SnS NCs. The efficiency plot (C/C₀) depicted in Fig. 3(c) further confirms the enhanced photocatalytic activity of the CNT-SnS NCs, demonstrating their ability to rapidly degrade CIP. Additionally, pseudo-first-order kinetic analysis, as shown in Fig. 3(d), revealed degradation rate constants of 0.032 min⁻¹ for SnS and 0.056 min⁻¹ for CNT-SnS NCs. The significantly higher degradation rate of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite underscores the synergistic effect of combining CNTs with SnS, which enhances charge separation, improves visible light absorption, and provides a larger active surface area. These results demonstrate the potential of CNT-SnS NCs as highly efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of organic pollutants in environmental remediation applications.

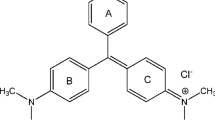

Similarly, the photocatalytic investigations were studied for the prepared nanocomposites against the MB dye solution and UV graph profile shown in Fig. 4 (a-b). The degrading efficiencies of the SnS and CNT-SnS were 87.02% & 96.96% under the same conditions. The efficiency plot (C/C0) of the MB solution is represented in Fig. 4c. The SnS, CNT-SnS NCs demonstrated the highest degradation ability, and it is described in the efficiency plot. Further, the rate constants for SnS and CNT-SnS against MB dye were 0.029/min and 0.048, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 4d. Table S1 shows the values of degradation percentage, experimental rate constant k, and R2.

Role of active species

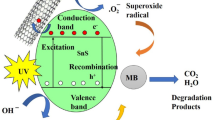

A comprehensive understanding of the photocatalytic reaction is essential for assessing its activity and the complex generation of reactive oxygen species, offering valuable insights into the efficacy of the catalyst. Following the doping process, the absorbance wavelength of CNT-doped SnS experiences a slight shift towards a lower redshift, as indicated by UV spectra measurements. The successful doping of CNT has influenced and resulted in the creation of oxygen traps, notably vacancies. Primarily, the catalyst generates three forms of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and it is crucial to determine which ROS has the most significant impact during photodegradation. CNTs can promote oxygen reduction, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (O₂⁻•), which are crucial for dye degradation. The scavenger study contributes to the comprehension of the mechanism underlying dye photodegradation over the CNT-SnS catalyst. In the experimental setup, we added EDTA as a scavenger for h+, methanol as a scavenger for OH, and p-BQ as a scavenger for O2− into the reaction solution. Figure 5(a) illustrates the efficiency of the scavenger studies. Including EDTA and p-BQ in the scavenger experiments implies significant alterations in the degradation process of both drug and dye, highlighting their active participation in the photocatalytic reactions. The ROS hole and the Hydroxyl radical play a major role in photocatalytic degradation.

The degradation mechanism for both dyes utilizing the prepared CNT-SnS is described as follows36:.

-

(i)

Production of excitons.

-

(ii)

Hydroxyl Radical Generation.

(iii) Superoxide Radical Generation.

(iv) Degradation of dye molecules.

In this current analysis, CNT-SnS NCs show a higher efficiency percentage than the NPs of SnS. The enhancement of catalyst behavior could be attributable to some basic factors: CNTs act as an excellent electron conductor, facilitating the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. The intimate contact between SnS and CNTs reduces charge recombination, increasing the efficiency of photocatalysis. Inhibiting photogenerated charge carrier recombination in CNT-SnS helps to enrich the degradation percentage. CNTs have excellent electrical conductivity, which facilitates electron mobility and minimizes charge recombination losses. The synergistic effect of CNTs and SnS improves the photocatalytic reaction rate. One method for increasing photocatalytic efficiency is to build composite photocatalysts by combining CNT with SnS to get CNT-SnS NCs. The advantage of composite photocatalysts is the dramatically improved charge separation and transfer efficiency caused by the difference in band levels between SnS and CNT-SnS. Huge reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced based on the sub-energy level of the conduction band. Figure 5b illustrates the reusability of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite for dye degradation over five consecutive cycles. Although handling catalysts in powder form can lead to material loss, appropriate compensation was applied to maintain consistent catalyst loading. The results indicate that the nanocomposite maintains its photocatalytic efficiency, showing no significant decrease in performance after five cycles37. These findings demonstrate the stability and durability of the CNT-SnS catalyst, highlighting its potential for practical applications in wastewater treatment. The photocatalytic dye degradation mechanism and schematic diagram are shown in Fig. 5c. Table S2 presents a comparison of CNT-SnS from the present work with previously reported photocatalysts38,39,40,41,42,43.

Electrochemical supercapacitor studies

Using CV measurement at various scan speeds ranging from 5 mVs− 1 to 100 mVs− 1 at the potential window range from 0 to 0.8 V in 6 M KOH solution, the electrochemical characteristics of the samples were initially examined. The scan rate-dependent CV curves of pristine SnS and CNT-SnS materials are shown in Fig. 6(a) and Fig. 7(a), respectively. The stability and rate capacity of the electrode material are shown in these tests at both the lowest and highest assessed scan rates. The anodic and cathodic peaks in the CV profiles of both materials showed the samples’ redox activity. The redox peaks maintained a highly symmetric structure even at the maximum scan rate of 100 mVs− 1, suggesting the existence and significance of faradaic processes. This symmetry implies that most redox processes can be reversed. The cyclic voltammetry curves of both materials have a distinct form that highlights the reversible redox reaction properties as compared to a typical electric double-layer capacitor. The anodic and cathodic peak changes observed with increasing scan rates are caused by strong electrochemical polarization44.

Figure 8(a) displays the CV curves for pristine SnS and CNT-SnS at a scan rate of 5 mVs− 1. Comparing the CV curves reveals that CNT-SnS performs better capacitively than pristine SnS, as seen by a larger curve area and higher current levels. This enhancement is attributed to the addition of CNTs, which increase the number of electrochemically active sites. The CV data generally show that adding CNTs to SnS significantly increases conductivity by forming new electron transport channels. The capacitance of SnS and SnS-CNT was evaluated using the galvanostatic charge/discharge technique at various current densities ranging from 0.5 to 3.5 Ag⁻¹. The GCD curves for SnS and CNT-SnS are displayed in Fig. 6(b) and 7(b), respectively. The non-triangular shapes of the GCD curves confirm that the materials are not electrostatic. The behavior of hybrid capacitors is demonstrated by the non-linear charge/discharge patterns of both materials. Moreover, there is some imperfect overlap between the charging and discharging curves. The following relation44 was used to compute the specific capacitance (Sc).

where m is the mass of the active material, V is the potential window, ∆t is the discharge duration, and I is the applied specific current.

Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements were performed at varying current densities ranging from 0.5 to 3.5 A g⁻¹. For pure SnS, the specific capacitance values were recorded as 546, 386, 219, 140, 85, 54, 20, and 35 F g⁻¹ at current densities of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.3, and 3.5 A g⁻¹, respectively. In contrast, the CNT-SnS nanocomposite demonstrated significantly enhanced capacitance values of 1792, 1482, 630, 432, 320, 252, 213, 189, and 168 F g⁻¹ across the same current densities, as illustrated in Figs. 6c and 7c. At lower specific current densities, a significant increase in specific capacitance was observed, which was attributed to the greater time allowed for electrolyte ions to intercalate into the electrode surface. Conversely, at higher current densities, the capacitance values decreased due to the insufficient time for ion diffusion and intercalation. Moreover, CNTs increase the number of electrochemically active sites; therefore, the CNT-SnS electrode shows a maximum specific capacitance of 1792 F g⁻¹ at a current density of 0.5 A g⁻¹.

An essential method for examining the frequency response at the electrode/electrolyte interface is electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), which offers information on the impedance profile via plotting the real (z′) and imaginary (z′′) components. The frequency range in which the Nyquist plot of the SnS. The CNT-SnS samples were recorded was 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz, as shown in Fig. 6 (d) and Fig. 7 (d), respectively. The EIS analysis of the SnS, CNT-SnS based supercapacitor were interpreted using the equivalent circuit model R₁+(Q₂‖R₂) + Q₃, revealing notable changes in the impedance parameters of before and after GCD cycling. In this configuration, R1 represents the solution resistance which includes ionic resistance of the electrolyte and contact resistance with in cell. The Q2 is constant phase element (CPE) shows imperfect capacitive behavior and surface roughness effects and R2 is charge transfer resistance, which shows the faradaic processes at the electrode-electrolyte interface. Further, the Q3 represents the Warburg impedance. The interpreted value for before GCD, the R1 was 0.0868Ω, which slightly decreased to 0.0892Ω after GCD, signifying stable electrolyte and contact resistance. The double-layer capacitance of Q2 showed a low difference; particularly, it shows the better electrode activation of electroactive sites in post-cycling. A significant improvement was observed in R₂, which decreased from 1.299 Ω before cycling to 5.781 Ω after cycling, implying enhanced redox reaction kinetics and improved electrode–electrolyte interaction. The second CPE of Q3 associated with pseudocapacitive contributions remained high, slightly increasing from before GCD to after GCD. The quality of fitting is excellent in both cases, confirming that the equivalent circuit appropriately describes the system’s electrochemical behavior. Overall, these findings indicate that the SnS–CNT composite retains good electrical conductivity and capacitive behavior even after cycling, highlighting its potential as a stable and efficient electrode material for supercapacitor applications.

Several factors contribute to the high super capacitive performance of the CNT-SnS nanocomposite: (i) The improved electrical conductivity due to the CNT backbone provides a highly conductive network for the SnS semiconductor, facilitating easy charge transport, lowering electron recombination, and reducing internal resistance. (ii) The incorporation of CNTs and SnS creates a synergistic effect, enhancing overall charge storage due to their complementary properties. Particularly, the combination of faradaic and non-faradaic processes is enabled by the hybrid structure of tin(II) sulfide (SnS) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs). SnS contributes to the pseudo capacitance through reversible redox reactions involving the Sn²⁺/Sn⁴⁺ couple, while CNTs provide a high surface area and excellent electrical conductivity to support electric double-layer capacitance and ensure rapid electron transfer. The CNT network also helps mitigate the volume changes in SnS during cycling, thereby improving structural stability and enhancing cycle life. The pseudocapacitive behavior of SnS can be represented by the following redox reaction occurring at the electrode–electrolyte interface:

Here, OH⁻ ions from the electrolyte participate in the surface redox reaction, contributing to the charge storage mechanism. (iii) Enhanced ion transport, resulting from the composite’s porosity, improves electrolyte diffusion and ion movement. This is clearly confirmed by the reduced semicircle in the impedance spectra. (iv) Lastly, CNT-SnS undoubtedly has a larger surface area for charge accumulation compared to pure SnS, further boosting capacitance (v).

The embedding of CNTs in pure SnS expands the number of accessible electroactive sites by decreasing this aggregation and promoting de-aggregation. Furthermore, adding CNTs enhances the electrical conductivity of the composites, which enhances their overall electrochemical performance in a synergistic manner45. The longer discharge time seen for the CNT-SnS composite in comparison to pristine SnS, as illustrated in Fig. 8(b), reflects this improvement. These findings demonstrate that the composite material significantly improves the power characteristics of hybrid supercapacitors. The CNT-SnS nanocomposite’s resilience and strong capacitance retention are further demonstrated by the cycling stability investigation. The most crucial feature of a supercapacitor that determines its practical use is its cyclic stability, which is depicted in Fig. 8(c). The material exhibits remarkable endurance and consistent electrochemical performance, retaining 80.4% of its initial capacitance after 5000 cycles at a current density of 3.0 A g− 1, which confirms that the CNT-SnS has high and stable electrochemical performance. Figure 8(d) shows the three-electrode cell setup for electrochemical supercapacitor analysis. Table S3 presents a comparison of CNT-SnS from the present work with previously reported electrochemical supercapacitors46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54.

Conclusion

In summary, tin sulfide (SnS) nanoparticles and SnS-incorporated CNT nanocomposites were successfully synthesized via a hydrothermal method. Advanced characterization techniques, including XRD, FE-SEM, EDS, HR-TEM, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy, were employed to elucidate the structural, morphological, and compositional properties of the SnS-MWCNT nanocomposite. The integration of SnS with MWCNTs significantly enhanced the material’s photocatalytic and electrochemical performance. The HRTEM analysis confirmed an average particle size of approximately 50 nm of SnS. The band gap of pristine SnS was calculated as 2.2 eV, while the CNT-SnS nanocomposite exhibited a reduced band gap of 1.8 eV, enhancing its visible light absorption. The SnS-CNT nanocomposite exhibited outstanding photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation, achieving degradation efficiencies of 96.97% for methylene blue (MB) and 97.77% for ciprofloxacin (CIP). The photocatalytic mechanism, driven by the generation of reactive oxygen species under visible light, was thoroughly investigated, providing insights into the material’s high efficiency in environmental remediation. Moreover, the high electrical conductivity of MWCNTs, coupled with the layered structure of SnS, facilitated efficient ion intercalation, resulting in a large electrochemically active surface area and superior charge storage capabilities. The SnS-MWCNT electrode demonstrated exceptional electrochemical performance, achieving a remarkable specific capacitance of 1792 F g⁻¹ at a current density of 0.5 A g⁻¹, along with excellent cycling stability, retaining over 80% of its initial capacitance after 5000 cycles. These results underscore the dual functionality of the SnS-MWCNT nanocomposite, highlighting its potential as a high-performance material for both energy storage and photocatalytic applications. This study provides a robust foundation for the development of multifunctional nanocomposites for sustainable energy and environmental technologies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Additional raw datasets (e.g., characterization spectra and photocatalytic and electrochemical supercapacitor measurements) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abhilash, M. R., Akshatha, G. & Srikantaswamy, S. Photocatalytic dye degradation and biological activities of the Fe2O3/Cu2O nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 9, 8557–8568 (2019).

Ajmal, A., Majeed, I., Malik, R. N., Idriss, H. & Nadeem, M. A. Principles and mechanisms of photocatalytic dye degradation on TiO2 based photocatalysts: A comparative overview. RSC Adv. 4, 37003–37026 (2014).

Alahmari, S. D. et al. Development of Mn doped cete as an environmental purifier for photodegradation of noxious methylene blue dye in water. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 188, 111909 (2024).

Gümüş, D. & Akbal, F. Photocatalytic degradation of textile dye and wastewater. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 216, 117–124 (2011).

Fareed, I. et al. A comparative study of oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions in alkaline, acidic and neutral media using SnS2/C catalyst. Carbon Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42823-025-00894-7 (2025).

Abdul, M., Fareed, I., Hussain, A. & Asim, M. SNanostructured Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Photocatalytic and Electrochemical Applications. Journal of electrochemistry 31(1), 2410001 (2011).

Suryawanshi, S. R., Warule, S. S., Patil, S. S., Patil, K. R. & More, M. A. Vapor-liquid-solid growth of one-dimensional Tin sulfide (SnS) nanostructures with promising field emission behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 2018–2025 (2014).

Ali, Z. et al. Harnessing Z-scheme charge transfer in SnS/ZnWO4 hybrid for efficient methylene blue photodegradation. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 190, 109338 (2025).

Yue, G. H., Wang, L. S., Wang, X., Chen, Y. Z. & Peng, D. L. Characterization and optical properties of the single crystalline SnS nanowire arrays. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 4, 359–363 (2009).

Ghazali, A., Zainal, Z., Hussein, M. Z. & Kassim, A. Cathodic electrodeposition of SnS in the presence of EDTA in aqueous media. Sol Energy Mater. Sol Cells. 55, 237–249 (1998).

Peng, Y. et al. Metal-organic framework (MOF) composites as promising materials for energy storage applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 307, 102732 (2022).

Li, X. et al. MXene chemistry, electrochemistry and energy storage applications. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 389–404 (2022).

Nengzi, L., chao, Yang, H., Hu, J., Zhang, W. & Jiang, D. ming ao. Fabrication of SnS/TiO2 NRs/NSs photoelectrode as photoactivator of peroxymonosulfate for organic pollutants elimination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 249, 117172 (2020).

Azeez, F. et al. The effect of surface charge on photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using chargeable Titania nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–9 (2018).

Malekkiani, M., Heshmati Jannat Magham, A., Ravari, F. & Dadmehr, M. Facile fabrication of ternary MWCNTs/ZnO/Chitosan nanocomposite for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and antibacterial activity. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–22 (2022).

Fareed, I., Farooq, M. H., Khan, M. D., Tahir, M. & Butt, F. K. An efficient multifunctional SnS2/g-C3N4 hierarchical Nanoflower catalyst for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic applications. Ceram. Int. 50, 36004–36017 (2024).

Fareed, I. et al. Unveiling novel SnS2/Zn2V2O7 composite for water splitting and ascorbic acid detection. Surf. Interfaces. 58, 105757 (2025).

Dar, M. A., Govindarajan, D. & Dar, G. N. Facile synthesis of SnS nanostructures with different morphologies for supercapacitor and dye-sensitized solar cell applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 20394–20409 (2021).

Chauhan, H., Singh, M. K., Hashmi, S. A. & Deka, S. Synthesis of surfactant-free SnS nanorods by a solvothermal route with better electrochemical properties towards supercapacitor applications. RSC Adv. 5, 17228–17235 (2015).

Kumar, S., Thomas, B. & Ranjan, V. A. Comprehensive review on CNTs and CNT-Reinforced composites: Syntheses, characteristics and applications. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101546 (2020).

Hemalatha, K., Ette, P. M., Madras, G. & Ramesha, K. Visible light assisted photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes on TiO2–CNT nanocomposites. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 73, 72–82 (2015).

Manuscript, A. & Materials Chemistry, A. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA13136A (2020).

Fareed, I. et al. Fundamentals and perspectives on materials for bifunctional electrocatalysis. Adv Sci. 12(38), e09902 (2025).

Henry, J., Mohanraj, K., Kannan, S., Barathan, S. & Sivakumar, G. Structural and optical properties of SnS nanoparticles and electron-beam-evaporated SnS thin films. J. Exp. Nanosci. 10, 78–85 (2015).

Mukherjee, A. & Mitra, P. Structural and optical characteristics of SnS thin film prepared by SILAR. Mater. Sci. Pol. 33, 847–851 (2015).

Alsalhi, S. A. et al. Development of a CeTe/rGO nanosized composite for photoreduction of heavy metal in the aquatic environment. J. Electron. Mater. 53, 4553–4563 (2024).

Sohila, S., Rajalakshmi, M., Ghosh, C., Arora, A. K. & Muthamizhchelvan, C. Optical and Raman scattering studies on SnS nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 5843–5847 (2011).

Hortikar, S. S. et al. Synthesis and deposition of nanostructured SnS for semiconductor-sensitized solar cell. J. Solid State Electrochem. 21, 2707–2712 (2017).

Zhang, G., Fu, Z., Wang, Y. & Wang, H. Facile synthesis of hierarchical SnS nanostructures and their visible light photocatalytic properties. Adv. Powder Technol. 26, 1183–1190 (2015).

Khan, K. et al. Structural, electrical, and photocatalytic properties of Y-type hexaferrite/carbon Dot composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 1793 (2023).

Alharbi, F. F. et al. Investigation of photoreduction of cr (VI) and electrocatalytic properties of hydrothermally produced novel CoFe2O4/ZnO nanostructure. Solid State Sci. 143, 107278 (2023).

Alenad, A. M. et al. Visible light driven Ni doped hematite for photocatalytic reduction of noxious methylene blue. Mater. Res. Bull. 165, 112306 (2023).

Abudllah, M. et al. Facile fabrication of ternary CuO/CuS/ZnS for photodegradation of methylene blue. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 60, 569–580 (2023).

Malumyan, S. A. et al. Simultaneous Effect of Diameter and Concentration of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Cement Mortars: With and without Biosilica. Nanomaterials. 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14151271 at (2024).

Hughes, K. J. et al. Review of carbon nanotube research and development: materials and emerging applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 18695–18713 (2024).

Fareed, I. et al. N–ZnO/g-C3N4 nanoflowers for enhanced photocatalytic and electrocatalytic performances. Phys. E Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 164, 116053 (2024).

Khan, M. D. et al. Novel N-doped ZnO and O-doped g-C₃N₄ heterojunction: enhanced photocatalytic degradation and robust electrochemical biosensing of ascorbic acid. Diam. Relat. Mater. 151, 111752 (2025).

Das, D. & Dutta, R. K. A novel method of synthesis of small band gap SnS nanorods and its efficient photocatalytic dye degradation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 457, 339–344 (2015).

Dashairya, L., Sharma, M., Basu, S. & Saha, P. SnS2/RGO based nanocomposite for efficient photocatalytic degradation of toxic industrial dyes under visible-light irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 774, 625–636 (2019).

Yao, K., Liu, Y., Yang, H., Yuan, J. & Shan, S. Polyaniline-modified 3D-spongy SnS composites for the enhanced visible-light photocatalytic degradation of Methyl orange. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 603, 125240 (2020).

Behera, C., Ghosh, S. P., Kar, J. P. & Samal, S. L. Facile synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic activity of Ag-SnS nanocomposites. New. J. Chem. 44, 11684–11693 (2020).

Dharmana, G., Gurugubelli, T. R., Masabattula, P. S. R., Babu, B. & Yoo, K. Facile Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity of Hydrothermally Grown Cu2+-Doped ZnO-SnS Nanocomposites for MB Dye Degradation. Catalysts 12, (2022).

Chowdhury, A. P., Shambharkar, B. H., Ghugal, S. G., Umare, S. S. & Shende, A. G. Ethylene glycol mediated synthesis of SnS quantum Dots and their application towards degradation of Eosin yellow and brilliant green dyes under solar irradiation. RSC Adv. 6, 108290–108297 (2016).

Sathish Kumar, P., Prakash, P., Srinivasan, A. & Karuppiah, C. A new highly powered supercapacitor electrode of advantageously united ferrous tungstate and functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Power Sources. 482, 228892 (2021).

Liu, P. et al. CNTs induced irregular 2d nanosheet SnS composites as active materials of electrodes for capacitive Deionization. Desalin. Water Treat. 209, 37–47 (2021).

Duangchuen, T., Karaphun, A., Wannasen, L., Kotutha, I. & Swatsitang, E. Effect of SnS2 concentrations on electrochemical properties of SnS2/RGO nanocomposites synthesized by a one-pot hydrothermal method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 487, 634–646 (2019).

Chauhan, H., Singh, M. K., Kumar, P., Hashmi, S. A. & Deka, S. Development of SnS2/RGO nanosheet composite for cost-effective aqueous hybrid supercapacitors. Nanotechnology 28, 025401 (2017).

Mishra, R. K., Baek, G. W., Kim, K., Kwon, H. I. & Jin, S. H. One-step solvothermal synthesis of carnation flower-like SnS2 as superior electrodes for supercapacitor applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 425, 923–931 (2017).

Barik, R., Devi, N., Perla, V. K., Ghosh, S. K. & Mallick, K. Stannous sulfide nanoparticles for supercapacitor application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 472, 112–117 (2019).

Parveen, N. et al. Facile synthesis of SnS2 nanostructures with different morphologies for High-Performance supercapacitor applications. ACS Omega. 3, 1581–1588 (2018).

Ravuri, S., Pandey, C. A., Ramchandran, R., Jeon, S. K. & Grace, A. N. Wet chemical synthesis of SnS/Graphene nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor electrodes. Int. J. Nanosci. 17, 1–8 (2018).

Chakraborty, I., Chakrabarty, N., Senapati, A. & Chakraborty, A. K. CuO@NiO/Polyaniline/MWCNT nanocomposite as High-Performance electrode for supercapacitor. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 27180–27190 (2018).

Ranjithkumar, R. et al. Enhanced electrochemical studies of ZnO/CNT nanocomposite for supercapacitor devices. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 568, 51–59 (2019).

Dağcı Kıranşan, K. & Topçu, E. SnS2-gC3N4/rGO composite paper as an electrode for High-Performance flexible symmetric supercapacitors. Synth Met 264, 116390 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors G. M. and N. V. express their gratitude to the management and the Director (Innovation) of Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, for providing access to laboratory facilities and for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.V. designed the study, prepared the samples, wrote the Results and Discussion section and the initial draft, and carried out subsequent revisions. S.S. contributed to the electrochemical experiments. G.N. supported the photocatalytic experiments. G.M. design and preparation of the samples and discussion about the photocatalytic and electrochemical studies. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkatesh, N., Sivaramakrishnan, S., Nagaiah, G.P. et al. Synergistic CNT-SnS nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic dye degradation and supercapacitor applications. Sci Rep 15, 42324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26453-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26453-8