Abstract

The visceral adiposity index (VAI) is an indicator of visceral fat dysfunction associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Neck circumference (NC) is a common anthropometric measure of upper-body fat. This study evaluated the association between NC and VAI in a rural Thai population using data from the Health Outcomes and Risk Factors in Rural Communities in Thailand (HARRIT) study (2017–2022). Elevated VAI was defined as > 2.98, while a large NC was considered ≥ 35 cm in men and ≥ 32 cm in women. Multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses were used to assess the relationship between NC and VAI. The study included 2,160 adults with a mean age of 55.6 years, 65.5% of whom were women. The average NC was 33.6 cm, and 63.4% of participants had a large NC. The mean VAI was 6.3, with 75.5% classified as having an elevated VAI. A large NC was significantly associated with a higher VAI (adjusted β = 2.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.91–2.71). Participants with a large NC had a 26% higher prevalence of elevated VAI (adjusted prevalence ratio [APR] = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.19–1.33). For individuals under 60, the APR was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.23–1.44); for those aged 60 and above, it was 1.17 (95% CI: 1.09–1.26). In conclusion, NC is positively associated with VAI among rural Thai adults. This highlights the need for further research to explore the relationship between NC and ASCVD outcomes and to establish sex- and age-specific NC cutoffs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a significant health issue and a major metabolic risk factor that increases the likelihood of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)1,2,3. This problem impacts public health worldwide, including in Thailand. Over the past decade, substantial evidence has shown that obesity rates are rising across various populations, including in rural communities4,5,6,7.

Metabolic indicators play a crucial role in assessing and predicting the risk of various chronic diseases, particularly ASCVD8,9,10. Existing studies demonstrated the relationship between visceral adiposity index (VAI) and the risk of ASCVD11,12. An extensive study among 306,680 Chinese adults with hypertension demonstrated that elevated VAI (≥ 2.8) increased 19% higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)12.

Neck circumference (NC) is a surrogate anthropometric measurement for upper body subcutaneous fat (SF)13. Numerous studies demonstrated that a larger NC is positively related to obesity,14 high BP,15 and various cardiometabolic risk factors16. A longitudinal study in Chinese adults revealed that higher NC was associated with an increased risk of the composite of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–1.83) per 1 standard deviation (SD) increase17. The study also indicated that those with high NC (≥ 38.5 cm in men or ≥ 34.5 cm in women) had a 2.2 times higher risk of CVD17.

Existing evidence indicated that both elevated visceral adiposity and large NC predict the occurrence of future CVD events. However, the evidence concerning the relationship between NC and visceral adiposity is both inconsistent and limited. A community–based study conducted in China revealed a positive relationship between NC and visceral fat area (VFA), as evaluated through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)16. In contrast, hospital–based CT scanner data indicated no significant association between NC and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) after adjusting for age14. In Thailand, several studies focusing on specific populations demonstrated an association between NC and waist circumference (WC),18 high BP,15,19, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)20.

In Thailand, a low– and middle–income country (LMIC), half of the population still resides in rural areas with limited access to resources, including healthcare services21. Unfortunately, evidence regarding the association between NC and visceral adiposity, particularly from community–based studies in these rural areas, is scarce. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the association between NC and visceral adiposity, as assessed by the VAI, among Thai adults residing in a rural community. Additionally, we examined the effect of age modification on the association between NC and elevated VAI.

Methods

Study design and subjects

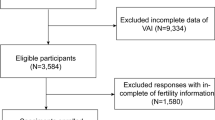

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis to determine the association between NC and VAI using baseline data from the Health Outcomes and Risk Factors in Rural Communities in Thailand (HARRIT) study. This dataset provided valuable information for our exploratory analysis. Briefly, the HARRIT is a cohort study conducted by the Phramongkutklao College of Medicine (PCM) across five villages in the Thakradan subdistrict and eight villages in the Phra Pleong subdistrict, initiated between 2017 and 2022. These communities serve as teaching sites for Community Medicine at PCM. They are located ~ 150 km from Bangkok, in the border areas of Thakradan subdistrict, Sanachaikhet District, Chachoengsao Province, and Phra Pleong subdistrict, Khao Chakan District, Sa Kaeo Province, central Thailand. In total, 9,263 adults aged 20 years or older were invited to participate (5,523 from Thakradan and 3,740 from Phra Pleong), of whom 2,170 (23.4%) enrolled.

For the present analysis, evaluating the association between large NC and elevated VAI, we calculated the required sample size based on Hu et al.17, assuming an effect size of 1.89 and 90% power. This yielded a minimum of 432 participants per group (≥ 864 total). Ultimately, we included 2,160 participants (99.5% of HARRIT participants) with complete data for VAI calculation in the analysis.

Data collection

For the HARRIT study, investigators provided information sheets detailing the project’s objectives and methods to eligible participants. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of data collection. If participants were unable to write, they could use their fingerprint on the consent form to indicate their agreement. The data collection involved health examinations, which included laboratory testing, BP measurements, and anthropometric assessments.

Participants were asked to fast for at least 12 h before their health examination. Blood samples were drawn by a medical technician and collected in tubes, which were then stored in a cold water bath before being sent to a central laboratory for analysis. The laboratory tests included total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high–density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low–density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and serum creatinine (Cr).

BP was measured by trained staff according to the Thai Guidelines for the treatment of hypertension,22 utilizing automated BP monitoring equipment (OMRON, HEM–7120, Kyoto, Japan). Participants were advised to refrain from consuming caffeine and smoking for at least 30 min prior to the measurement. Talking was prohibited during the measurement22. Three BP readings were obtained at one–minute intervals, and the averages of the final two readings were documented.

Anthropometric assessments, including body weight (BW), height, NC, and WC, were performed by trained technicians. BW and height were measured using a body composition monitor (OMRON model HBF–212, Kyoto, Japan) and a stadiometer (DETECTO, St. Webb City, MO, USA), respectively23. For NC, participants were asked to stand with the Frankfort horizontal plane, and the NC was measured at the midpoint between the mid–cervical spine and the mid–anterior neck to within 1 mm using plastic tape24. WC was measured at the umbilical level using a plastic tape.

Variables

This study’s outcome was VAI, which was calculated based on body mass index (BMI), WC, TG, and HDL cholesterol levels. BMI was determined by dividing BW in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). The VAI was calculated using specific formulas11: VAI for men = \(\frac{WC}{{39.68 + \left( {1.88 \times BMI} \right)}} \times \frac{{TG \left( {mmol/l} \right)}}{1.03} \times \frac{1.31}{{HDL \left( {mmol/l} \right)}}\); VAI for women = \(\frac{WC}{{36.58 + \left( {1.89 \times BMI} \right)}} \times \frac{{TG \left( {mmol/l} \right)}}{0.81} \times \frac{1.52}{{HDL \left( {mmol/l} \right)}}\). Regarding the previous evidence from a prior Chinese cohort study revealing an association between elevated VAI (> 2.98) and an increased risk of CVD12, in this study, we defined elevated VAI as greater than 2.98.

The exposure of interest was NC. We approached the NC variable in three ways: (i) continuous, (ii) categorized into four groups as quartiles, and (iii) divided into two groups, defined as large NC. We employed Youden’s statistic to establish the threshold for a large NC indicative of predicted elevated VAI. The cutoff for NC was 35 cm in men and 32 cm in women, with the area under the curve 0.61 (95% CI: 0.59–0.63), which was defined as a large NC. Details on the sensitivity and specificity of large NC for detecting elevated VAI are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 (StataCorp, 2021). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Baseline characteristics were summarized as percentages for categorical variables and as mean ± SD for continuous variables. Group comparisons were performed using χ2 tests, Student t-tests, or one-way ANOVA, as appropriate.

To provide robust evidence on the association between NC and the VAI, we used both linear and logistic regression models. Univariable and multivariable linear regression were used to evaluate the association between NC and VAI (continuous), reporting β coefficients with 95% CIs. We checked the model assumptions and evaluated heteroskedasticity using the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test, while assessing multicollinearity with variance inflation factors (VIFs). Multivariable models adjusted for rural community, age, sex, SBP, TC, LDL cholesterol, FPG, and serum Cr. For elevated VAI, we fit univariable and multivariable logistic regression and estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% CIs via marginal standardization (adjrr)25; we assessed model fit with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. We evaluated effect modification by age and performed analyses stratified by age groups of < 60 and ≥ 60 years. Sensitivity analyses addressed residual confounding and included quantifying potential unmeasured confounding using E-values (evalue package)26.

Ethics considerations

The HARRIT study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Royal Thai Army Medical Department, Bangkok, Thailand, on December 1, 2015 (Approval No. S053q/58). The study adhered to international ethical guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki, the Belmont Report, the CIOMS guidelines, and ICH–GCP. All participants provided written informed consent after reviewing the information sheet.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of 2,160 study participants. Of these participants, 53.8% resided in Chachoengsao province. The mean age of participants was 55.6 years, with the majority (50.3%) falling within the 40–59 age group. Most of the participants (65.5%) were women. The overall mean NC was 33.6 cm, with 1,370 participants (63.4%) classified as having a large NC. The mean BMI was 25.1 kg/m2, and the mean WC was 80.4 cm. The mean TG level was 178.1 mg/dL, while the mean HDL cholesterol level was 50.0 mg/dL. The mean VAI was 6.3, and 75.5% of participants had elevated VAI.

Relationship between baseline characteristics and elevated VAI

Table 2 illustrates the relationship between baseline characteristics and elevated VAI. Mean VAI differed by age group (p < 0.001) and was higher in women than in men (6.4 vs. 5.9; p = 0.035). The prevalence of elevated VAI was 78.6% in women versus 69.5% in men (p < 0.001). Mean VAI also differed across NC categories (p < 0.001), and the prevalence of elevated VAI was more common among participants with large NC (p < 0.001).

Linear regression model to determine the association between NC and VAI

Table 3 presents the association between NC and VAI. A positive association was observed, with an adjusted β coefficient of 0.41 (95% CI: 0.34–0.48). This association was significant for participants aged < 60 years (adjusted β-coefficient: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.26–0.42) and those aged ≥ 60 years (adjusted β-coefficient: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.40–0.64). A dose–response relationship was evident, with ascending quartiles of NC showing higher adjusted β coefficients for VAI: Q2 at 1.66, Q3 at 2.55, and Q4 at 3.73, relative to Q1. For NC evaluated in two categories, participants with large NC had an adjusted β-coefficient of 2.31 (95% CI: 1.91–2.71) for VAI compared to those with non-large NC.

Logistic regression model to determine the association between NC and elevated VAI

Table 4 presents the association between NC and elevated VAI. A significant association was found, indicating that larger NC associated with elevated VAI, yielding an adjusted PR of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.17–1.30), as shown in Fig. 1. Age modified this association (p-interaction = 0.004; Fig. 2), with adjusted PRs of 1.25 (95% CI: 1.16–1.35) for participants aged < 60 years and 1.22 (95% CI: 1.12–1.32) for those aged ≥ 60 years. A dose–response relationship was evident across NC quartiles, with adjusted PRs of 1.20, 1.33, and 1.49 for Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively, compared to Q1. Participants with large NC had an adjusted PR of 1.26 (95% CI: 1.19–1.33). For those aged < 60 years, the adjusted PR was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.23–1.44) compared to 1.17 (95% CI: 1.09–1.26) for those aged ≥ 60 years.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis for estimated E-values of unmeasured confounders is presented in Supplementary Table 2. The E-value for the observed adjusted PR of 1.26, which identifies the association between the unmeasured confounder and the large NC related to the elevated VAI, was 1.83.

Discussion

Our study identified a positive association between NC and visceral VAI in adults from rural Central Thailand. Elevated VAI was more prevalent in individuals with larger NC, and age influenced this association. These findings suggest that NC could be an effective tool for community health screening in rural settings to identify individuals with elevated VAI.

We found a significant positive association between NC and VAI through multiple approaches. Each additional centimeter increase in NC was linked to a 24% higher prevalence of elevated VAI. A clear dose–response relationship emerged when NC was divided into quartiles. Additionally, individuals with large NC experienced a 26% greater prevalence of elevated VAI compared to those with non-large NC. This study offers strong evidence of the association between NC and VAI in Thai adults in rural areas.

Comparison with previous studies

Our study assessed the VAI using anthropometric measurements and lipid profiles, defining elevated VAI as > 2.98 based on its association with increased CVD risk from a Chinese study12. Limited data exist on predicting VAI via NC in Thailand. A rural study found NC ≥ 37.5 cm in men or ≥ 32.5 cm in women linked to a 1.76 times higher hypertension prevalence15. A study in Bangkok identified optimal NC cutoffs for NAFLD at 37.07 cm for men and 32.07 cm for women20. Our findings indicated that the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for large NC in detecting elevated VAI was 60.9, with moderate sensitivity of 68.8% and low-to moderate specificity of 53.0%, making this the optimal cutoff for our population.

Previous studies revealed inconsistent results regarding the association between NC and visceral adiposity. A community-based study in China included 1,943 subjects assessed for VFA using a 3.0T clinical MRI scanner. This study demonstrated a significant positive relationship between NC and VFA, with β-coefficients of 0.13 in men and 0.14 in women16. Another study involving 177 Chinese patients assessed VATa using a 64 detector row Computed Tomography scanner. A positive correlation was observed between NC and VAT, with correlation coefficients (r) of 0.49 in men and 0.25 in women14. However, in a multivariable linear regression model adjusting for age, the association between NC and VAT was statistically nonsignificant for both sexes14.

Potential mechanisms

Several mechanisms may explain the positive association between NC and VAI. First, the visceral adiposity index was estimated to assess visceral adiposity dysfunction11. The NC is considered a surrogate marker for upper-body SF27, which is a primary source of circulating free fatty acids (FFA) and is more lipolytically active than lower-body SF28. Therefore, greater upper-body SF is associated with higher systemic FFA levels. Visceral adiposity plays a role in hepatic FFA delivery, and elevated FFA concentrations can induce insulin resistance, which is associated with excessive visceral fat29. Another mechanism may be explained by the potential correlation between NC and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), an inflammatory marker associated with the VFA30. Jamar et al. demonstrated a positive association between NC and PAI-1, even after adjusting for potential confounding factors such as age, sex, and BMI31.

Our findings revealed that age modifies the association between NC and elevated VAI on a multiplicative scale. In younger adults aged < 60 years, we found an adjusted PR for elevated VAI of 1.25. In contrast, the association was weaker among participants aged ≥ 60 years, with an adjusted PR of 1.22. The aging process in older adults is associated with progressive changes in total and regional fat distribution, which can have adverse health consequences. Older adults are more likely to accumulate visceral fat as body fat redistributes with age32,33. This phenomenon may weaken the relationship between NC and elevated VAI in individuals aged ≥ 60 years compared to younger individuals.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the largest community-based investigation exploring the relationship between larger NC and elevated VAI among adults in a rural Thai community. However, it has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships. Second, residual confounding may arise from limited data on socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to estimate the impact of unmeasured confounders. Third, our study involved 2,160 adults from 13 villages near Chachoengsao and Sa Kaeo provinces in rural areas, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Therefore, further research is needed in settings with diverse socioeconomic statuses. Lastly, the HARRIT study data showed a low response rate in recruiting community study participants at baseline, which may have led to selection bias and affected the representation of this population.

Implications and further directions

Existing evidence demonstrates that NC is positively associated with obesity, high BP, and metabolic syndrome15,18,19,20. It suggests that NC could be used as a screening tool to identify specific health conditions. For example, a study conducted in Thailand among patients with prediabetes showed an independent association between NC and WC18. Another study involving academic employees in Bangkok indicated that NC was associated with NAFLD20. Our community–based research in rural areas yielded valuable insights, showing the positive association between NC and VAI. Although VAI is estimated for visceral fat using MRI scanner assessment as the gold standard, it requires laboratory test results, including TG and HDL cholesterol, alongside anthropometric measurements such as WC and BMI. In the context of LMICs with limited resources, measuring NC is a straightforward, noninvasive, and cost–effective approach. Consequently, NC may serve as an effective tool for health screening in rural areas. NC may also be used to screen for visceral adiposity dysfunction and to identify individuals with elevated VAI, who represent a high-risk population for ASCVD. Additionally, NC can monitor changes in visceral adiposity over time34. Further studies in Thai populations should investigate the relationship between NC and ASCVD outcomes to derive and validate NC cutoffs that are specific to sex and age, while improving sensitivity and specificity.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that a larger NC was associated with higher VAI in Thai adults in rural areas. The prevalence of elevated VAI was higher in individuals with larger NC among all participants, including those under 60 years of age and those aged 60 and older. The effect of age modification on the association between NC and elevated VAI was observed. We highlight that NC could serve as an effective tool for community health screening in rural contexts to identify individuals with elevated VAI.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the HARRIT study, but restrictions apply to their availability. These data were used under license for the current study and are therefore not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Research Unit for Military Medicine (contact Boonsub Sakboonyarat via [boonsub1991@pcm.ac.th](mailto:boonsub1991@pcm.ac.th) ).

Abbreviations

- VAI:

-

Visceral adiposity index

- VFA:

-

Visceral fat area

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

- FFA:

-

Free fatty acids

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- HDL:

-

High–density lipoprotein

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Ritchie, S. A. & Connell, J. M. C. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 17, 319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005 (2007).

McGill, H. C. et al. Obesity accelerates the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in young men. Circulation 105, 2712 (2002).

Turpie, A. G. G., Bauer, K. A., Eriksson, B. I. & Lassen, M. R. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 1867 (2002).

Sakboonyarat, B. et al. Trends, prevalence and associated factors of obesity among adults in a rural community in Thailand: serial cross-sectional surveys, 2012 and 2018. BMC Public Health 20, 850 (2020).

Sakboonyarat, B. et al. Rising trends in obesity prevalence among Royal Thai Army personnel from 2017 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 12, 7726 (2022).

Aekplakorn, W. Thai National Health Examination Survey VI (2019–2020). https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbgj/znee/#p=187 (2019).

Phelps, N. H. et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 403, 1027 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Association between novel anthropometric indices and overactive bladder: a population-based study. Front. Nutr. 12, 1493792 (2025).

Zheng, J. et al. Positive association between cardiometabolic index and gallstones, with greater impact on women and those younger than 50 years: the NHANES 2017–2020 cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 25, 2130 (2025).

Guo, Q. et al. The association between cardiovascular health and obstructive sleep apnea symptoms: findings from NHANES. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1466752 (2024).

Amato, M. C. et al. Visceral Adiposity Index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care 33, 920–922 (2010).

Lv, D. et al. Novel metabolic indicators and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with hypertension: a primary-care cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 35, 103749 (2025).

Joshipura, K., Muñoz-Torres, F., Vergara, J., Palacios, C. & Pérez, C. M. Neck circumference may be a better alternative to standard anthropometric measures. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 6085159 (2016).

Li, H.-X. et al. Neck circumference as a measure of neck fat and abdominal visceral fat in Chinese adults. BMC Public Health 14, 1–7 (2014).

Soitong, P. et al. Association of neck circumference and hypertension among adults in a rural community Thailand: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16, e0256260–e0256260 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. Neck circumference as an effective measure for identifying cardio-metabolic syndrome: a comparison with waist circumference. Endocrine 55, 822–830 (2017).

Hu, T. et al. Neck circumference for predicting the occurrence of future cardiovascular events: a 7.6-year longitudinal study. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32, 2830 (2022).

Anothaisintawee, T., Sansanayudh, N., Thamakaison, S., Lertrattananon, D. & Thakkinstian, A. Neck circumference as an anthropometric indicator of central obesity in patients with prediabetes: a cross-sectional study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 4808 (2019).

Meelab, S. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of uncontrolled blood pressure among hypertensive patients in the rural communities in the central areas in Thailand: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 14, e0212572–e0212572 (2019).

Suwimol, S. et al. Neck circumference as a screening measure for identifying NAFLD among a group of academic employees in Bangkok, Thailand. PLoS ONE 17, 023653 (2022).

The World Bank. Thailand - Rural Population. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=TH (2024).

Kunanon, S. et al. 2019 Thai guidelines on the treatment of hypertension: executive summary. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 104, 1729–1738 (2021).

Viwatrangkul, P. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in a rural community, central Thailand. Sci. Rep. 11, 7083 (2021).

Amato, M. C., Giordano, C., Pitrone, M. & Galluzzo, A. Cutoff points of the visceral adiposity index (VAI) identifying a visceral adipose dysfunction associated with cardiometabolic risk in a Caucasian Sicilian population. Lipids Health Dis. 10, 183 (2011).

Norton, E. C., Miller, M. M. & Kleinman, L. C. Computing adjusted risk ratios and risk differences in Stata. Stata J. 13, 492 (2013).

Linden, A., Mathur, M. B. & VanderWeele, T. J. Conducting sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding in observational studies using E-values: the evalue package. Stata J. 20, 162 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Neck circumference as an independent indicator to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese men. Nutr. Metab. Lond. 12, 63 (2015).

Stabe, C. et al. Neck circumference as a simple tool for identifying the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: Results from the Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study. Clin. Endocrinol. Oxf. 78, 14563 (2013).

Ebbert, J. O. & Jensen, M. D. Fat depots, free fatty acids, and dyslipidemia. Nutrients 5, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5020498 (2013).

Shimomura, I. et al. Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat. Med. 2, 800 (1996).

Jamar, G. et al. Is the neck circumference an emergent predictor for inflammatory status in obese adults?. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67, 217 (2013).

Kuk, J. L., Saunders, T. J., Davidson, L. E. & Ross, R. Age-related changes in total and regional fat distribution. Ageing Res. Rev. 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2009.06.001 (2009).

Ou, M. Y., Zhang, H., Tan, P. C., Zhou, S. B. & Li, Q. F. Adipose tissue aging: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cell Death Dis. 13, 256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04752-6 (2022).

Cao, W. et al. Change of neck circumference in relation to visceral fat area: a Chinese community-based longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Obes. 46, 1633–1637 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the health workers at (1) Baan Nayao Health Promoting Hospital, Ta Kradan Subdistrict, Sanam Chai Khet District, Chachoengsao Province, (2) Sai Thong Health Promoting Hospital and (3) Na Khan Huk Health Promoting Hospital, Phra Pleong Subdistrict, Khao Chakan District, Sakaeo Province for their invaluable support throughout the study.

Funding

The present study was supported by Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Bangkok, Thailand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KJ, RR, MM, PH, and BS. Data curation: KJ and BS. Formal analysis: BS. Funding acquisition: RR, MM, PH and KJ. Investigation: KJ, RR, MM, PH and BS. Methodology: BS. Project administration: KJ. Visualization: BS. Writing – original draft: KJ and BS. Writing– review & editing: KJ, RR, MM, PH, and BS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jongcherdchootrakul, K., Rangsin, R., Mungthin, M. et al. Association between neck circumference and visceral adiposity index among adults in rural Thailand. Sci Rep 15, 39134 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26655-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26655-0