Abstract

Additive manufacturing enables the fabrication of next-generation electrical machines with unprecedented topological complexity and design freedom. Due to this design freedom, no consensus has been achieved on the optimal shapes for air-gapped soft magnetic cores —- flux guides — that maximize transmitted magnetic flux for a given volume while maintaining eddy current losses at an acceptable level and ensuring sufficient mechanical stiffness. We research topological optimality in terms of transmitting magnetic flux, while favouring mechanical stability when the amount of flux transmitted is similar. We demonstrate that the optimal core shape is close to a structure we term the ’H-comb’: a configuration of thin sheets interconnected by a central bridge, forming a double-sided comb in cross-section perpendicular to the magnetic flux flow. We also develop a mathematical framework for optimally dimensioning these flux guides, providing guidelines for determining appropriate sheet and gap thicknesses based on specific material properties and operating frequencies. We fabricated a series of H-comb-shaped magnetic cores and conducted flux measurements. Across the practically relevant frequency range, the deviation between theoretical predictions and experimental results remains below 10%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical machines are used in over 80% of the world’s energy conversion processes1. They currently conform to a limited number of standardized design templates. Customization is hindered by conventional manufacturing constraints. As additive manufacturing (AM) of electrical machines matures, we expect a shift toward application-specific optimized devices2. This will unlock innovation that reduces material requirements and improves energy efficiency3.

We assess the technological readiness (TRL) of additively manufactured electromagnetic components at level 44. Useful features have been identified in lab settings. However, commercial implementation remains limited to 3D printed windings for small-volume production5.

The primary challenge for AM soft magnetic cores-effectively mitigating eddy currents-remains unsolved. Traditional cores use thin, electrically insulated laminations to increase internal resistance. Current 3D-printing technologies struggle to replicate this solution, as combining ferromagnetic metals with electrical insulators is difficult. Furthermore, the minimum feature size (including air-gaps) of AM machines results in a lower fill factor. Consequently, neither high-frequency nor standard 50 Hz AM core applications have achieved competitive results6. Additionally, the extra costs of AM have not been justified by performance gains through 3D topology optimization.

Developing effective strategies to mitigate eddy current losses in AM soft magnetic cores is critical for realizing shape-optimized electrical machines. This topic is attracting significant research attention. Various approaches addressing limited multi-material capacity include:

-

using novel amorphous materials7;

-

forming layered metallic/intermetallic composites8;

-

intentionally introducing micro-cracks9;

-

functionally grading printed material with narrow insulating air-gaps perpendicular to flux paths.

These strategies aim to increase intra-core electrical resistance while leveraging AM production freedom. The air-gap approach has been most widely studied. It has involved extensive experimentation in various orientations and shapes10,11,12,13,14.

Current literature on AM cores with air-gapped structures reveals several key insights:

-

1.

AM cores show magnetic properties similar to mid-range silicon steel laminations (M400-50A)14. However, they have a significantly lower material fill factor (50–70% vs. 90–95%)14.

-

2.

Optimizing AM cores requires balancing eddy current suppression against magnetic material fill factor. This balance is crucial since AM air-gaps (0.2–0.5.2.5 mm) are typically ten times wider than insulating layers in traditional laminations (0.01 mm).

-

3.

With current technology, overhanging air-gaps below 30–45 degrees must be avoided. This is due to quality issues that cause electrical shorting12.

-

4.

State-of-the-art AM magnetic cores utilize fractal space-filling curves in their design, i.e., Hilbert15 or Peano11 curve-based structures, for minimizing eddy current losses. These structures show useful properties if printed in parallel to the build direction (e.g., test rods for magnetic characterization), but if adapted into more complicated structures with overhanging elements show suboptimal performance due to overhang related printing defects12,16.

-

5.

The connection strategy consolidating the elements is critical for effective eddy current suppression. Connections must account for possible printing defects while minimizing the characteristic width (cross-sectional area-to-perimeter ratio) of structures. Core rigidity elements should avoid creating closed loops within cross-sections17.

-

6.

Metal AM systems are most effective with high-aspect-ratio thin structures and air-gaps parallel to the process scan plane. More symmetrical shapes are limited by overhang constraints. This leads to defects or excessive supports that compromise performance.

However, a systematic, physics-based analysis of the problem is absent from the literature. Prior studies reveal several critical gaps: First, the focus has been almost exclusively on mitigating eddy currents, without a rigorous framework to calculate the total usable magnetic flux. This is particularly important for high-frequency applications, where the skin effect can cause field reversal and partial flux cancellation within the material. Second, existing design advice is often reduced to the heuristic guideline that lamination thickness should be “around the skin depth,” lacking a precise, analytical framework for optimization. Finally, the search for an optimal core topology has relied on trial-and-error prototyping18or machine-learning-driven approaches that have produced complex, sometimes impractical, structures without yielding a fundamental understanding of the optimal shape, cf19.

To address these gaps, it is first necessary to develop a foundational analytical framework that can be rigorously tested. While the ultimate promise of AM lies in creating novel three-dimensional topologies that are inaccessible to conventional lamination techniques, such complex geometries are not suitable for developing and validating a fundamental physical model. Therefore, this study focuses on a simple, essentially two-dimensional (2D) toroidal geometry. Although a toroid itself does not represent a practical application where AM would outperform traditional methods, it serves as an ideal model system. Its simplicity allows for the derivation of an exact analytical solution, enabling a direct and unambiguous validation of our theoretical framework against experimental results. The validated principles established here can then serve as a reliable foundation for the future design and optimization of more complex components where AM holds a true advantage.

To build this foundational framework, we combine experimental and theoretical approaches to:

-

Identify the optimal shape for AM flux guides that maximizes the magnetic flux transfer capacity of the core.

-

Develop a mathematical framework for dimensioning air-gapped cores to achieve optimal fill factor and minimal iron losses based on specific material properties and frequency requirements.

-

Determine practical frequency limitations for AM soft magnetic cores based on manufacturing constraints.

-

Establish guidelines for connecting segregated loss-mitigating structures.

General considerations about the shapes of soft magnetic cores

For typical applications, a sinusoidal magnetic field \(B = B_0 e^{\mathrm i\omega t}\) is applied to the magnetic core. Soft magnetic cores should maximize total magnetic flux transmitted within a fixed size — equivalent to maximizing the average flux:

Maximizing \(\left\langle \Phi \right\rangle\) involves mitigating regions where the magnetic field is significantly attenuated or has an unfavourable phase due to skin effect.

It is instructive to view skin effect as magnetic flux diffusion (cf20.):

where \(\mu\) is material differential permeability and \(\sigma\) conductivity; a derivation of this equation is provided in the Supplementary methods. This equation, in its general form, remains valid for a nonlinear \(B-H\) dependence. However, the nonlinear case is not analytically tractable. Therefore, all subsequent analysis is based on the linear approximation, as detailed in Sect. "General considerations: eddy current losses". For sinusoidal boundary conditions of circular frequency \(\omega\), the periodic solutions of Eq. (2) decay exponentially into the bulk: the magnetic field is mostly present in a skin layer of depth

along the outer perimeter of the flux guide. The skin effect simplifies mathematically for one-dimensional geometry and linear \(B-H\) dependence yielding20

Visualization of the skin effect and magnetic flux accumulation inside a semi-infinite ferromagnetic plate occupying the region \(x \ge 0\), as described by the linear diffusion model (Eq. 2). The real magnetic field Re(B) (solid blue line), oscillates as it penetrates the material, while its amplitude |B| (dotted red line) decays exponentially. The green dash-dotted line shows the amplitude of the total magnetic flux integrated from the surface to a depth x, \(|\int _0^x B \textrm{d}x|\), which starts decreasing beyond ca 2.2 skin depths due to partial flux cancellation from field reversal. The corresponding phase lag of the integrated flux is shown by the dashed brown line.

This analysis reveals two key design principles: first, no region within the ferromagnetic material should be much farther than \(\delta\) from the core’s outer perimeter, as magnetic flux in such regions is exponentially small; second, to maximize the fill factor, the flux guides should be as thick as possible. These conditions are contradictory in nature: too thick flux guides have flux-free central regions, and thin flux guides have a small fill factor. Hence, there is an optimal flux guide thickness that is on the order of \(\delta\). Since all parts of the flux guide must have the same optimal thickness, one can conclude that there are two optimal geometries for the flux guides:

-

space-filling sheets of constant thickness \(t\sim \delta\), possibly folded to fill the space (e.g., the Hilbert shape shown in the left pane of Fig. 2) or connected via bridges similarly to the H-comb shown in the right pane of Fig. 2);

-

space-filling arrays of cylindrical/prismatic shapes depicted in Fig. 3 (a-b).

In sheet-based designs, adjacent sheets should be connected by only a single bridge. The additional bridges, whether intentional or not, create enclosed air gap segments. These bridges act as diffusion barriers that prevent magnetic fields reaching the enclosed air gap segments, and hence, diffusing into the flux-guiding sheets from both sides. Among the cylindrical/prismatic shapes, hexagonal prisms achieve the highest fill factor and merit consideration alongside sheets. We would like to point out that having these singular bridges adds mechanical stability and contributes to fill factor without causing disproportional losses. Designs such as21 would benefit from adding bridges.

Cross-sections of toroidal flux guides in the form of space-filling topologies of constant sheet thickness: Hilbert shape (left) and H-comb (right). Both shapes can be represented as graphs where light gray squares denote vertices and dark gray rectangles represent edges connecting the vertices. Hence, Euler graph formula can be used to show that the material filling factor of all such shapes are strictly equal.

Cross-sections of flux guides with cylindrical/prismatic shapes (a,b) and sheet-like shapes (c). For all the shapes, the scale 2a shows the doubled area-to-perimeter ratio. Dashed loops mark model streamlines used for simplified calculation of energy dissipation, and the shaded area shows the area A embraced by one such model streamline.

In our design, the bridge thickness was not rigorously optimized. Instead, it was set equal to the plate thickness based on a zeroth-order approximation. In this approach, a bridge segment is treated as being electromagnetically equivalent to a short plate segment, which implies its optimal thickness should be on the same order of magnitude. A full optimization of the bridge geometry would require a dedicated numerical analysis of the 2D skin effect within its non-trivial boundaries, a task beyond the scope of this foundational study. However, any potential performance gain from such an optimization is expected to be minimal, as the bridges constitute a small fraction of the total magnetic volume.

Now, let us show that all space-filling sheet-based designs with uniform sheet thickness t and uniform gap thickness g, such as the Hilbert curve or Peano curve22,23, cf. Fig. 2, exhibit exactly the same filling factor and similar magnetic performance, assuming that their sheet thicknesses and air gaps are uniform throughout the core. Consider a cross-section of such a design and suppose it covers a rectangular area of dimensions \(a\times b\); for the gaps to be uniform, \(a+g\) and \(b+g\) have to be multiples of \(t+g\), i.e., \(a=n(t+g)-g\) and \(b=m(t+g)-g\), where n and m are integers. So, we can construct a grid of \(n\times m\) equally spaced squares, see the gray squares in Fig. 2.

In order to be space filling, the sheet needs to pass through each square of this grid: we can consider the sheet’s cross-section as the squares connected by bridges of width g and length t; these bridges are shown in dark gray in Fig. 2. The whole sheet represents a connected graph where the centres of the squares are the vertices and the bridges are the edges. Now we can apply the Euler graph formula

where e denotes the number of edges, f the number of faces, and \(v=nm\) the number of vertices. Since the graph is connected and has no enclosed air gap segments, the number of faces is one. Therefore, the number of bridges \(e=nm-1\), i.e., the material fill factor is

which simplifies to \(\chi \approx t/(t+g)\) when \(nm\gg 1\).

Apart from the fill factor, what also affects the performance of flux guides is the degree to which the skin effect depletes the middle parts of the sheets. For the same sheet thickness, one can expect a similar depletion. However, at corners where the sheet turns 90 degrees, the depletion is likely slightly more pronounced because the diffusion is more non-uniform compared with the straight sheet case, as the area-to-perimeter ratio is locally less favourable. Therefore, one can expect that the magnetic performance of the H-comb design is marginally better than other designs with more convoluted sheets.

To sum up, since all the space-filling sheet designs have almost identical magnetic performance, secondary considerations such as mechanical robustness and manufacturing process complexity can guide the choice between different space-filling sheet topologies.

Maximal mechanical rigidity is achieved when the free-hanging segments of sheets are as short as possible to maximize flexural rigidity. In this regard, the best possible design is the H-comb: the length of the free-hanging segments is only about half of the cross-sectional diameter. Another important aspect to consider is how short and straight the air gaps are, to facilitate post-manufacturing removal of scrap particles. Again, the H-comb is a clear winner in this regard.

General considerations: eddy current losses

In addition to the total transmitted flux, one should also consider the energy dissipation due to eddy currents. While a more detailed analysis of this aspect will be left for future studies, here we provide an estimation of such losses under the assumption that these are small, which is equivalent to the condition \(\delta \gg t\). While a design violating this condition will have unmagnetized core regions (“magnetic voids”), implying a non-optimality for moderate frequencies, this is a practical necessity in high-frequency AM. This occurs because manufacturing constraints impose a minimum feature thickness (ca. 0.4 mm in our case) to maintain permeability, while high frequencies (e.g., \(\ge\) 200 Hz) reduce the skin depth to below this limit (\(\delta \le 0.3\) mm). In such cases, the formation of magnetic voids is an unavoidable consequence of the operating conditions.

In all our calculations, we assume a 2D geometry, where quantities depend only on the cross-sectional coordinates (x, y). This model is precise when the characteristic size of the flux guide along the magnetic field is much larger than its size across the field. If these two dimensions are of a similar order of magnitude, the magnetic field across the cross-section becomes inhomogeneous. This would necessitate further specific optimization, for which our current design would serve as an effective starting point.

Furthermore, we neglect the nonlinearity of the B-H relationship. This simplification is necessary to develop a general analytical framework, which is the primary aim of this study. While we acknowledge nonlinearity is an important factor, its effects can be reasonably approximated within our linear model by selecting an appropriate effective permeability based on the B-H curve and the range of B and H values under the operating conditions, provided the material does not enter deep magnetic saturation. A full treatment of nonlinearity would require numerical methods or perturbation theories, which are beyond the scope of this foundational analytical work.

In all our calculations, we assume a 2D geometry with the magnetic field along the z-axis, with quantities dependent on x and y only. This assumption corresponds to toroidal shapes with the length of the flux guides (the length of the circular toroidal perimeter of the core) L greatly exceeding the diameter \(d_c\) of the poloidal cross-sections (the ones shown in Fig. 2). Finally, we neglect the nonlinearity of the B-H relationship.

In this section, we estimate the ohmic dissipation by assuming that the current streamlines and hence, the electric field lines form a concentric family of shapes which are equidistant from each other and from the perimeter of the core as shown in Fig. 3 with dotted lines. Strictly speaking, this assumption is valid only for a cylindrical core. However, for simple polygonal shapes such as squares and hexagons, the error we introduce by using this approximation is negligible. One way to give an upper bound on the error is considering the circumscribing disks for simple polygonal shapes. These cylinders would transport more magnetic field in total compared to the other bars, while being overall less efficient per volume due to being thicker at every point. As such, one can find margins of error around the ratio of the areas, i.e. around 10% for hexagons.

Under this simplification, the distance between two infinitely close electric field lines remains constant along their entire length, i.e., the electric field is constant along each field line. To establish a relationship between the electric field strength \(E\) and the geometric properties of the field lines, we employ Faraday’s law: \(E\ell ' = \dot{B} A\), where \(A\) represents the surface area enclosed by the field line (shaded in Fig. 3), and \(\ell '\) represents its total length (note that for the outermost field line, \(\ell '=\ell\)). From here we can express

The instantaneous dissipation rate \(P_F\) can now be found by integrating the Joule heating over the surface area: \(P_F =\int E^2\sigma \,\textrm{d}A=\int \sigma \dot{B}^2A^2\ell '^{-2}\,\textrm{d}A.\)

In this integral, if the field lines form a self-similar family of shapes as it happens, e.g., in the case of hexagons and squares, the surface area A enclosed by a field line (shaded in Fig. 3) is proportional to the squared perimeter \(\ell '\), cf. Fig. 3 (a-b). Consequently, \(A^2 \ell '^{-2}\) is proportional to A, i.e., we can write \(A^2\ell '^{-2}=\alpha A\), where \(\alpha\) is a constant whose value can be expressed in terms of \(\mathcal {A}\) - the full cross-sectional area of the core, and \(\ell\) - the full perimeter of the core, \(\alpha =\mathcal {A}/\ell ^2\). Then, \(P_F =\int \sigma \dot{B}^2\alpha A\,\textrm{d}A =\sigma \dot{B}^2\alpha \mathcal {A}^2/2=\frac{1}{2}\sigma \dot{B}^2\mathcal {A}^3\ell ^{-2}\).

If the field lines have strongly elongated shapes for which the width is much smaller than the perimeter (such as the shapes shown in the bottom row of Fig. (3), \(\ell '\) remains almost constant throughout the full family of the field lines, \(\ell '\approx \ell\). So, the integral evaluates to \(P_F=\sigma \dot{B}^2\int A^2\mathrm d A/\ell ^2 = \frac{1}{3}\sigma \dot{B}^2\mathcal A^3\ell ^{-2}\). Based on these two expressions obtained for \(P_F\), we can express the dissipation rate volume density as

here \(k=\frac{1}{2}\) for self-similar shapes (squares, hexagons), and \(k=\frac{1}{3}\) for elongated shapes (sheets, H-comb). Also, we have introduced the area-to-perimeter ratio a that can be interpreted as the effective width of the cross-section of the core. In the case of elongated shapes, a is equal to half of the full width while in the case of a square, it is equal to a quarter of the side length, as shown in Fig. (3). Eq. 7 is an important result showing that the eddy-current-related dissipation rate depends almost only on the area-to-perimeter ratio a.

Flux density in planar and cylindrical flux guides

Two flux guide designs can be analyzed analytically with relative ease: wide flat plates (where \(\ell \gg t\)) and cylinders. Luckily, the H-comb design conjectured by us to be optimal, is approximated very well with wide sheets: the neighbourhood of the bridges (where the shape cannot be considered as a wide sheet) occupies only relatively small area. Assuming a linear \(B-H\)-relationship, the average magnetic flux density in wide sheets can be calculated as

where t is the plate thickness, and g is the gap size; this expression is derived in the Supplementary methods.

The flux \(\Phi\) guided through a cylinder of radius R is derived in the Supplementary methods; average flux density transmitted through cylindrical flux guides in a hexagonal arrangement is found by dividing the flux \(\Phi\) by the hexagonal cell area \(2\sqrt{3}(R+g/2)^2\), resulting in

where \(J_0\) represents the Bessel function of the first kind, and R represents the radius of the cylinder.

Among self-similar shapes, hexagonal prisms are expected to be the best-performing ones, due to the following qualitative arguments. For a fixed effective width a, circular shapes are the best in terms of the transported flux per flux guide’s cross-sectional area. Indeed, the centre of any self-similar shape has the largest distance from the perimeter, and hence the smallest magnetic field. For cylinders, the entire perimeter is at an equal distance from the centre, and hence, diffusion from the entire perimeter contributes to the magnetic field at the centre. In the case of shapes with corners (triangles, squares, hexagons), corners have increased distance from the centre and contribute less efficiently to the magnetic field therein, resulting in a decreased average flux; the more acute the angles of the prisms, the more pronounced the effect is. The difference between the average flux by hexagonal prisms and cylinders appears to be fairly small, but hexagons pack significantly better than cylinders, resulting in approximately a 10% better fill factor. Therefore, the best self-similar shapes are hexagons, and a good estimate for the average flux through an array of hexagonal flux guides can be obtained by multiplying the prediction of Eq. (9) by 1.1.

In Fig. 4 the average flux densities predicted by Eqs. (8,9) are plotted against \(2a=2\mathcal A/\ell\) (that is equal to the thickness of a sheet t and to the radius R of a cylinder) for \(\delta ={0.6}{\textrm{mm}}\) and \(g={0.2}{\textrm{mm}}\). Pay attention to the fact that the maximum flux density for cylinders is more than 10% inferior to that of sheets, implying that sheets work better than cylinders and hexagons.

Average flux density in space-filling sheets and in hexagonal array of cylinders, plotted against plate thickness for fixed skin depth \(\delta ={0.6}{\textrm{mm}}\) and gap width \(g={0.2}{\textrm{mm}}\) using Eq. (8).

The optimal gap size \(t_{\textrm{opt}}\) can be found through differentiation of Eqs. (8,9). The result for sheets is plotted in Fig. 5. As we can see, for the not-too-high frequencies when the skin depth is larger than the gap width, \(1\le t_{\textrm{opt}}\le 1.6\) so that one can approximate \(t_{\textrm{opt}}\approx 1.3\). It should also be kept in mind that the average flux as a function of t has a fairly wide maximum, as shown in Fig. 4.The maximum becomes particularly wide at the limit of small gap widths. For instance, consider traditional laminations with typical values \(g\approx {5}{{\upmu m}}\) and \(\delta \approx {2.5}{\textrm{mm}}\). While the maximum \(\left\langle B\right\rangle /B_0\approx 0.994\) occurs at \(t/\delta \approx 0.5\), the flux remains within 5% of this maximum from \(t/\delta =0.04\) to \(t/\delta =1.3\).

At higher frequencies (when the skin depth is smaller than the air gap), the average flux will be reduced too much to be of practical value. However, it is interesting to note that at the limit of very small skin depth, the optimal sheet thickness tends to \(t\approx 2.3\delta\). This behavior can be explained by the fact that if we were to use \(t> 2.3\delta\), the magnetic field would reverse its direction inside the flux guide, resulting in partial flux cancellation.

The red central curve represents the theoretically optimal thickness \(t_{\textrm{opt}}\) in units of skin depth for space-filling sheets, calculated according to Eq. (8) and shown as a function of the skin-depth-to-gap-width ratio. The remaining two red curves correspond to \(\pm 3\)% departure from the maximal flux. The blue curve shows the average flux at \(t_{\textrm{opt}}\). Experimental data points are shown as correspondingly coloured dots; the experimentally optimal thicknesses are calculated using interpolation between the experimental data points; error bars correspond to 5% uncertainty.

Experimental methods: sample design

The heat treatments were performed in an RD-G vacuum furnace (R.D. Webb Company Inc.) at the Taltech’s Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. The samples were prepared with an SLM-280 (SLM Solutions) laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) 3D-printer at the Taltech’s Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering.

The raw materials and processing parameters for both printing and post-processing were identical to those developed in4, as summarized in Table 1. The only difference from the previous study was the use of border scanning parameters (for the samples with \(n=12\) and \(n=10\), border scanning alone was employed without conventional hatching due to feature thinness). The samples were produced from spherical Fe-Si powder consisting of 3.7% silicon, trace elements (Mn, Cr, Ni, C), and iron (balance). Post-printing thermal treatments were conducted in a Webb-107 graphite chamber vacuum furnace at temperatures up to 1200\(^{\circ }\)C.

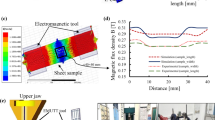

Five toroidal cores, shown in Fig.6, were prepared with identical general dimensions: an outer diameter of 60 mm, inner diameter of 50 mm, and a rectangular \(5{\textrm{mm}}\times {5}{\textrm{mm}}\) cross-section in an H-comb shape. Each core had thin air gaps of target thickness \(g={0.20}{\textrm{mm}}\) integrated into the cross-section, forming 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 thin laminations of equal width, connected by a thin bridge at the center. The samples were labelled N4 through N12 according to their number of laminations.

After printing, processing, and annealing, the physical toroid measurements were taken using a digital scale (KERN 440-45N with ± 0.1g accuracy) and a high-precision digital caliper. The fill factor \(\chi\) of the samples was evaluated based on the measured toroid’s average length \(l_t\), mass m, envelope cross-sectional area S, and the average absolute density \(\rho ={7610}{\textrm{Kgm}}^{-3}\) of the flux guide material, as follows:

The actual thicknesses of the flux guide laminations and the air gaps, as well as their uniformity, were evaluated using images from the YXLON FF35 CT metal computed tomography (CT) system with a continuous cone beam scan method.

The 256-bit grayscale tomographic images of flux guide cross-sections were converted to black-and-white bitmaps using two methods. In the first approach, the conversion threshold was chosen so that the relative number of black pixels (pixels inside the flux guide material) matched the fill factor determined from mass and dimensional measurements. Figure 6 shows typical cross-sectional images thresholded using this method.

In the second approach, pixel brightness histograms were created, showing two local maxima corresponding to the gap area and flux guide material. The local minimum between these maxima, representing the point of highest contrast, was identified as the threshold separating the two regions.

To calculate the gap width and lamination thickness, 5mm-wide rectangular cuts (covering either upper or lower halves of the laminations, but excluding the bridge) were taken from the bitmaps, and average thicknesses were calculated based on the number of black and white pixels, along with the number of laminations and gaps. Table 2 shows the results; the two methods yield similar results. We determined the first method to be more reliable, as the CT system’s brightness response curve may have nonlinearity that could slightly bias the contrast detection method results. Therefore, further calculations are based on method 1 results.

There is an imperative need to avoid the formation of unintended bridges within the structure. Such bridges would disallow free flow of the magnetic field by creating larger loops Foucault currents could flow through. We chose a gap width of 0.2mm which reliably avoids such bridges. Narrower gaps would reduce repeatability of results by producing random bridges.

The magnetic properties of the printed cores were measured using an in-house ring measurement setup following European standards EN 60404-624 and EN 60404-425. The current on the excitation and voltage on the sensing coil of the magnetic ring measurement setup were obtained with a sampling frequency of 200 kHz on a DEWE2-M data acquisition system, from which the average field strength H and the average flux density \(\bar{B}\) (averaged over the iron area) were calculated using the following expressions:

Here \(N_1\) and \(N_2\) denote the number of turns of the primary coil and secondary coils, respectively, i — the instantaneous current value, e — the instantaneous induced electromotive force, \(l_t\) — the toroid’s average length, and S — the toroid’s cross-sectional area. In all experiments, sinusoidal excitation current was used. Each sample was magnetized up to average flux density of \(1 \pm {0.01}{\textrm{T}}\) at quasi-static conditions, from which quasi-static relative DC permeability was determined. The AC measurements were taken at 10, 50, 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000 Hz, and for each sample, at the critical frequency \(f_0\) by which the skin depth is equal to the lamination thickness,

where \(\sigma =1.76 \times 10^{6}\Omega ^{-1}{\textrm{m}}^{-1}\)26. The upper frequency of 1000 Hz encompasses the material’s entire practical operating range: at higher frequencies, the skin depth would become significantly smaller than the minimum manufacturable feature size (0.2 mm), leading to a predictable and severe performance decline from material underutilization.

At small feature sizes (such as sheet thickness), spatial confinement limits the ability of material grains to coarsen and align, which in turn leads to lower macroscopic relative permeability. The data in Table 3 confirm this effect is negligible above a certain threshold; for feature sizes of 0.38 mm and greater, the material’s magnetic characteristics are highly consistent, fluctuating by less than 5%. This demonstrates that as long as the processing conditions in Table 1 are maintained, samples with reliable and repeatable performance can be produced.

Experimental results

The summary of the physical and DC magnetic properties measurements is outlined in Table 3. The surface temperature of the cores was monitored during all AC measurements using thermal imaging to ensure thermal stability. The maximum temperature increase due to internal heat dissipation remained below 10\(^{\circ }\)C, confirming that any temperature-induced changes to material properties had a negligible effect on the magnetic measurements.

The produced samples exhibited slightly wider air-gap widths than intended, measuring between 0.23–0.25.23.25 mm instead of the targeted 0.20 mm. The fill factor of the produced samples varied between 84% (N4 sample) and 50% (N12 sample).

The comparison of experimental and theoretical results involves evaluating the permeability. Due to the nonlinearity of the B-H curve, permeability can be defined in a multitude of ways. In order to select the most suitable definition for our purposes, note that what enters Eq. (2) in the non-linear case is the differential permeability \(\mu \equiv \frac{\textrm{d}{B}}{\textrm{d}{H}}\) that depends on the local instantaneous value of H. Since we want our linear theoretical model that uses a constant \(\mu\) to approximate the nonlinear reality as precisely as possible, we need to select a value of \(\mu\) from within the range of values observed at a typical point within the flux guide during the full magnetization cycle. We opted for calculating \(\mu\) as the slope of the direct current B-H curve at the half amplitude of B, i.e., \({0.5}{\textrm{T}}\) for increasing H and \({-0.5}{\textrm{T}}\) for decreasing H. The two obtained values were averaged for the final permeability value that is used below when comparing the theoretical predictions with the experimental results, and that is listed in Table 3. The direct current B-H curve was used because it reflects the material’s magnetic properties, while the AC B-H curves provide only an integral flux-current relationship that depends on the nonlinear skin-effect in a complicated way.

The measured DC relative differential permeability \(\mu _r=\mu _0^{-1}\frac{\textrm{d}{\bar{B}}}{\textrm{d}{H}}\) at \({0.5}{\textrm{T}}\) decreased from 10200 (N4 sample) to 4600 (N12 sample), indicating that there is a significant reduction in the average crystallographic grain sizes that incurs a deterioration of the samples’ DC magnetic properties. The table includes also characteristic frequencies \(f_0\) at which the sample lamination thickness is equal to the skin depth, \(\delta =t\), and the H-field strength \(H_1\) by which \(\bar{B}={1}{\textrm{T}}\) is achieved, and the coercive force \(H_c\) for cyclic process with 1 T-amplitude of the B-field.

Discussion and guidelines

Our experimental results align well with our theoretical estimates. This is demonstrated in Fig. 7. Here, the experimental data points are plotted onto the colour-coded contour plot of the theoretical dependence [Eq. (8)]. This plot is also supplied with the optimal-thickness-curve (optimal thickness for the given gap width as a function of skin depth), shown in red. Another visualization of this data is shown in Fig. 8, where the relative deviation of experimental data from the theory predictions is plotted against the skin depth.

As we can see, there is a fairly good match. The main exception is in the case of skin depths much smaller than the plate thickness, \(\delta \ll t\), i.e., at very high frequencies. The reason for this mismatch lies in the fact that our theory is linear while the flux guide material is nonlinear.

To provide a deeper analysis of the nonlinearity, we must consider the magnetic diffusion process described by Eq. (2). The diffusion rate is governed by the local, instantaneous differential permeability. For our linear model to best approximate this nonlinear reality, we selected an effective permeability based on the moderate field strengths (\(B\sim {0.5}{T}\)) present throughout the material in the near-optimal operating regime.

However, in the high-frequency regime where the skin depth is much smaller than the feature thickness, the flux density is significantly weaker in the guide’s interior. Our material exhibits a considerably lower differential permeability in these weak-field regions (\(B\sim {0.1}{T}\)), which leads to a much higher magnetic diffusivity. Our linear model, using a constant permeability, predicts an exponentially decaying field. In reality, the field does not decay exponentially to zero but rather penetrates until its amplitude is just weak enough that the corresponding high diffusivity yields a skin depth on the order of the remaining feature thickness. This deeper, unaccounted-for flux is strong enough to explain why our theory underestimates the experimental results at high frequencies.

Experimentally measured transmitted flux density (scattered dots) are plotted against the theoretical value (coloured plane) according to Eq. (8). Red line represents theoretically optimal values.

Conclusion

We have shown that under the constraints of modern additive manufacturing technologies, such as the minimal gap width g between flux guides, sheet-like topologies are optimal in terms of the average magnetic flux density. Honeycomb arrays of hexagonal prisms show a similar but slightly inferior performance: with the same gap width, their average flux density is approximately 10% smaller (see Fig. 4).

Furthermore, we have shown that all sheet-like topologies with the same sheet thickness and the same air gap width provide almost the same average magnetic flux density. We have also shown using the Euler graph formula that the material filling factor of the H-comb shapes is strictly equal to the filling factor of equivalently dimensioned space-filling-curves-based shapes (such as the Hilbert shape and the Peano shape, cf. Fig. 2). Therefore, the choice between different options can be made based on secondary considerations such as mechanical robustness and ease of processing (e.g. post-printing scrap metal removal from the air gaps). As a result, the recommended design is the H-comb shape shown in the right pane of Fig. 2. This finding simplifies the design challenge by establishing that the optimal topology is geometrically simple, removing the need to explore more complex shapes through algorithmic searches.

We have derived an exact expression for the average flux density under the assumptions of toroidal geometry and a linear B-H curve, both for sheet-like cross-sections and circular cross-sections [see Eqs. (8,9)]. To verify our analytical results, we printed a series of H-comb-shaped toroidal flux guides and measured the average flux density in them for different input frequencies. The experimental results are in reasonably good agreement with the theory in the practically relevant range of frequencies, i.e., when the skin depth is larger than the sheet thickness and, hence, the average flux density is not small. At higher impractical frequencies, the match between our linear theory and experiment is less good because the nonlinearity of the B-H curve comes into play.

The primary contribution of this work is the establishment of a precise, analytical design rule for the optimal thickness of these AM structures. This optimum depends on the frequency and permeability, conveniently parametrized by the skin depth \(\delta\), as shown in Fig. 5. While the common heuristic is to use a thickness of “around one skin depth,” our framework provides a more precise rule for the practically relevant range \(\delta \ge g\): the optimal thickness is approximately \(1.3\delta\). The quantitative value of this precision is tangible; for example, choosing a suboptimal thickness of \(0.8\delta\) instead of the optimal \(1.3\delta\) results in a 5% reduction in average magnetic flux. By providing a clear, analytically-derived rule for sizing, this framework replaces iterative, simulation-based parameter sweeps with a direct calculation, establishing a solid foundation for the design of future AM magnetic cores.

The analytical framework presented here establishes a foundational methodology for optimizing magnetic flux in AM cores. To improve the precision and usability of this approach, future work will proceed in two key directions. The first is a comprehensive characterization of core losses, supplemented with calorimetric measurements, to quantify the trade-offs between eddy current mitigation and fill factor. The second is the development of an analytically tractable approximation to account for material nonlinearity, which will enhance the model’s accuracy for high-frequency applications.

Data availability

The full experimental data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Data availability

The full experimental data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Bramerdorfer, G., Tapia, J. A., Pyrhonen, J. J. & Cavagnino, A. Modern electrical machine design optimization: Techniques, trends, and best practices. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 65(10), 7672–7684. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2018.2801805 (2018).

Selema, A., Ibrahim, M. N. & Sergeant, P. Metal additive manufacturing for electrical machines: Technology review and latest advancements. Energies 15(3), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15031076 (2022).

Wrobel, R. & Mecrow, B. A comprehensive review of additive manufacturing in construction of electrical machines. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 35(2), 1054–1064. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEC.2020.2964942 (2020).

Tiismus, H., Kallaste, A., Vaimann, T., & Rassõlkin, A. State of the art of additively manufactured electromagnetic materials for topology optimized electrical machines, Additive Manufacturing 55, 102778 (2022a) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102778

Applications - additive drives, https://www.additive-drives.de/en/applications/, accessed: 2021-09-22

Goodall, AD., Nishanth, FNU., Severson, EL., & Todd, I. Loss performance of an additively manufactured axial flux machine stator with an eddy-current limiting structure, Materials Today Communications 35, 105978 (2023a) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.105978

Jung, H. Y. et al. Fabrication of fe-based bulk metallic glass by selective laser melting: A parameter study. Materials & Design 86, 703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2015.07.145 (2015).

Goll, D. et al. Additive manufacturing of soft magnetic materials and components. Additive Manufacturing 27, 428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.02.021 (2019).

Goodall, AD., Chechik, L., Mitchell, RL., Jewell, GW., & Todd, I. Cracking of soft magnetic fesi to reduce eddy current losses in stator cores, Additive Manufacturing 70, 103555 (2023b) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103555

Manninen, A. et al. The mitigation of eddy-current losses in ferromagnetic samples produced by laser powder bed fusion. IEEE Access 10, 115571. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3218669 (2022).

Klein, C., May, C., & Nienhaus, M. Magnetic performance of eddy current suppressing structures in additive manufacturing, Actuators 13 (2024a) https://doi.org/10.3390/act13030094

Goodall, AD., et al. Geometrical control of eddy currents in additively manufactured fe-si, Materials & Design 230, 112002 (2023c) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112002

Andreiev, A., Haag, J., Virtanen, G. & Grund, S. Soft-magnetic behavior of laser beam melted fesi3 alloy with graded cross-section. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 296 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2021.117183 (2021).

Tiismus, H., et al. Laser additively manufactured magnetic core design and process for electrical machine applications, Energies 15, (2022b) https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103665

Plotkowski, A. et al. Influence of scan pattern and geometry on the microstructure and soft-magnetic performance of additively manufactured fe-si. Additive Manufacturing 29, 100781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.100781 (2019).

Gadiyar, N., Goodall, A. D., Todd, I. & Severson, E. L. Characterization of an axial flux machine with an additively manufactured stator. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 38, 2717. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEC.2023.3285539 (2023).

Croset, G., Soupremanien, U., Baffie, T. & Delette, G. Designing size-controlled air cavities to reduce iron losses of 3d printed ferromagnetic parts: Modelling and experimental results. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2023.171703 (2024).

Macknojia, AZ., et al. Additive manufacturing of fe-6.5 wt.%si transformer steel toroidal cores: Process optimization, design aspects, and performance, Materials & Design 241, 112883 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.112883

Babu, A. V. K., Bhat, R. S. & Razvi, S. M. Topology optimization and additive manufacturing of soft magnetic core structures for improved inductive performance. Additive Manufacturing 55, 102830 (2022).

Landau, LD., & Lifshitz, EM. Electrodynamics of Continuous Media, 2nd ed., Course of Theoretical Physics, 8 ( Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1984)

Kolano-Burian, A., et al. Spiral-like geometry as an efficient way to minimize high-frequency losses in 3d printed fesi6.5 toroidal cores using selective laser melting technology, Materials Today Communications 45, 112410 (2025) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.112410

Klein, C., May, C., & Nienhaus, M. Magnetic performance of eddy current suppressing structures in additive manufacturing, Actuators 13, (2024b) https://doi.org/10.3390/act13030094

Plotkowski, A. et al. Design and performance of an additively manufactured high-si transformer core. Materials & Design 194, 108894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108894 (2020).

European standard en 60404-6: Magnetic materials - part 6: Methods of measurement of the magnetic properties of magnetically soft metallic and powder materials at frequencies in the range 20 hz to 100 khz by the use of ring specimens (2004)

European standard en 60404-4: Magnetic materials - part 4: Methods of measurement of d.c. magnetic properties of iron and steel (2002)

Tiismus, H., Kallaste, A., Vaimann, T. & Rassõlkin, A. Ac magnetic loss reduction of slm processed fe-si for additive manufacturing of electrical machines. Energies 14, 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14051241 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Estonian Research Council grant (PRG-1827). The heat treatment of the samples was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant (PRG-1145).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TP made theoretical calculations, data analysis and figures, and contributed to manuscript writing; JK worked out framework for theory and data analysis, and contributed to manuscript writing; HT produced the samples, performed the experiments, and contributed to manuscript writing; IV made tomographic measurements; TV supervised the experiments; AK conceived the concept, supervised the project, secured funding, and contributed to manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Plopeanu, T., Kalda, J., Tiismus, H. et al. Optimal shape of additively manufactured magnetic cores. Sci Rep 15, 42501 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26678-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26678-7