Abstract

This study reutilizes microcrystalline chitosan extracted from shrimp shells, which is then modified with fibrous phosphosilicate (FPS) to synthesize FPS-CS. It is subsequently incorporated into cement based composites. This research sought to incorporate FPS-CS to improve the performance and durability of Portland cement, particularly enhancing its resistance to sulfates. Simultaneously, FPS-CS was added to cement mortar, and the aggregation behavior of FPS-CS, along with the hydration process and microstructural characteristics of the mortar, was analyzed. The study revealed that adding FPS-CS improved the toughness, physical properties, and durability of the cement samples. The addition of FPS-CS led to a decrease in both the factors associated with chloride ion migration and the volume of voids within the material. Furthermore, the ability of cement mortar to resist compression forces was improved with the presence of FPS-CS as opposed to control samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lightweight concrete has emerged as an essential material in modern construction, with its applications and usage expanding significantly in recent years. In many cases, it offers greater efficiency and cost effectiveness compared to conventional concrete. Its defining features are reduced density and excellent workability, which make it highly suitable for diverse structural and non structural purposes1,2,3. Nevertheless, despite these advantages, lightweight concrete still faces several limitations such as lower water retention, higher drying shrinkage, decreased durability, and increased cracking susceptibility. These drawbacks primarily stem from its highly porous microstructure, particularly the interconnected pore network, which restricts its wider utilization in construction projects4,5,6. Mohd Zamzani et al. showed that as the density of lightweight concrete decreases, the number of larger voids significantly increases7. Furthermore, lightweight concrete exhibits lower ultrasonic pulse velocity and becomes more prone to cracking at reduced densities8.

Concrete is among the earliest construction materials identified as a promising platform for nanotechnology driven advancements9,10,11. Previous research has demonstrated that the incorporation of dense nanostructured components can strengthen interfacial bonding and reduce the permeability of foamed systems12. Consequently, nanoparticles such as starch, alumina, and silica have been widely utilized to enhance the structural integrity and performance of preformed foams. Moreover, investigations on particle stabilized foams at larger scales have revealed that the inclusion of such nanoparticles can effectively suppress bubble growth for extended periods up to four days thereby improving the overall stability of the material13,14,15,16.

The growth of green chemistry is driven by the use of chitosan (CS) as a natural polymer, owing to its biocompatibility, affordability, biodegradability, and non toxic nature17. Chitosans are biodegradable, and chemically stable polysaccharide. Chitosans serve for supporting ions of transition metals such as rhodium18, cerium19, copper20, nickel21, ruthenium22,23, and others. Chitosan supported metal complexes have been effectively utilized in catalytic processes such as oxidation24, hydrogenation25, and in Heck and Suzuki reactions26. Furthermore, to enhance catalytic efficiency, hybrid materials of silica (CS-SiO2) have been synthesized in various structures, including silica beads27, hierarchical porous materials28, and composite membranes29. In contrast to synthetic fibers like basalt, glass, and carbon fibers, organic fibers such as CS provide benefits like biodegradability, renewability, light weight, and cost effectiveness, making them ideal for reinforcing cement based materials30,31,32,33. Research has shown that incorporating organic fibers into cement-based composites can significantly improve their compressive strength, toughness, and flexibility30. However, determining the compatibility of organic fibers with cement based structures continues to be a significant challenge34. Recent advances indicate that chitosan can also serve as a functional additive in cementitious composites by improving interfacial bonding, refining pore structure, reducing permeability, and enhancing resistance to crack propagation35. Its cationic nature and abundant hydroxyl and amino groups enable strong chemical interactions with cement hydration products, while its film-forming ability can act as a barrier to aggressive ion ingress36. Despite these promising characteristics, systematic studies on chitosan’s role in improving the durability of cement-based materials particularly against multiple degradation mechanisms such as chloride/sulfate attack, freeze thaw cycles, and acid exposure remain scarce17.

Our research team developed fibrous phosphosilicate (FPS) nanoparticles characterized by a distinctive structure, where the pore sizes progressively expand from the core to the outer surface37 FPS exhibited a high specific surface area due to the presence of pores within its structure, while its unique morphology and design greatly enhanced the accessibility of active sites. Additionally, the 3D architecture formed a hierarchical pore structure with macropores, which can further enhance the mass transfer of the reactant. In this study, we propose a novel strategy for functionalizing FPS with shrimp shell derived chitosan through covalent grafting, yielding the FPS–CS composite. This material is hypothesized to combine the structural advantages of FPS with the functional benefits of chitosan, thereby acting as both a microstructural filler and a multifunctional additive in cement mortars.

Building on our ongoing interest in the development of nanoparticles for cement based composites, a new approach was proposed for preparing the desired nanocomposites by modifying chitosan, a natural resource, along with extracting solutions from shrimp shells, to advance the industrial applications of chitosan. In this study, chitosan was extracted from shrimp shells and supported on fibrous FPS. The study explored the effect of different NaOH blend intensities and immersion durations on the bulk reduction of FPS-CS, aiming to facilitate the effective use of FPS-CS in cement based composites. A variety of analyses, such as TEM, FTIR, SEM, and XRD, were performed to examine the changes in the main components of FPS-CS. The physical properties and self generated contraction of the cement-based mixtures containing FPS-CS were evaluated, and the effect of NaOH mixture pre-soaking on CS was also investigated. The objectives of this work are threefold: (1) to synthesize and characterize FPS–CS using advanced microscopic and spectroscopic techniques; (2) to systematically investigate its influence on the hydration, workability, mechanical performance, and dimensional stability of cement mortars; and (3) to evaluate the improvement in durability under harsh chemical and environmental conditions. The novelty of this research lies in being the first to utilize shrimp shell derived chitosan functionalized FPS in cementitious systems, offering a sustainable, waste-derived, and performance-enhancing approach to green construction materials.

Experimental

Substances and methods

In this research, ordinary Portland cement (PO 52.5), supplied by Fars Cement Company (Iran), was utilized as the principal binder material. The foamed concrete mixtures were prepared using standard fine sand, Portland cement, a protein based foaming agent (FFO-NP), and distilled water as the essential components. The Portland cement conformed to the BS12 standard specifications, exhibiting a specific surface area of 3312 cm2/g and a specific gravity of 3.18. Its physical properties and chemical composition are listed in Table 1, with supplementary information in Table 2. Additionally, magnetite nanoclusters (DFNS@Fe₂Mo₈) with a purity exceeding 98.5% were utilized (see Table 3). A total of seven FC mixtures were prepared, each designed with a target density of 1000 kg/m3 and incorporating different DFNS@Fe₂Mo₈ concentrations (0.00%, 0.10%, 0.15%, 0.20%, 0.25%, 0.30%, and 0.35%). The water-to-cement and sand-to-water ratios were maintained at 0.40 and 1:1.4 (Table 4).

Standard method for preparing FPS

This compound was synthesized based on previous reports17.

Extracted chitosan from shells of shrimp

Chitosan extracted from shrimp shells based on previous reports17.

Standard method for preparing FPS-CS

This compound was synthesized based on previous reports17.

Substances and methods

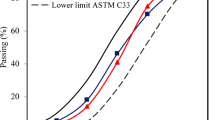

To prepare the fine concrete mixtures, a combination of distilled water, FPS-CS, standardized fine sand, a protein-based foaming agent, and Portland cement was utilized. The Portland cement, conforming to BS12 specifications, exhibited a specific gravity of 3.24 and a surface area of 3301 cm2/g, with further physical and chemical characteristics detailed in Tables 1 and 2. The fine sand, compliant with BS12620 standards, featured particle sizes between 0.19 mm and 3.02 mm and a specific gravity of 2.97 g/cm3. As outlined in Table 3, the protein derived foaming agent, possessing a density of 1.02 kg/L, was selected based on its efficiency in generating discrete, uniform, spherical air voids an essential feature for enhancing the thermal and acoustic properties of lightweight concrete. Additionally, magnetite nanoparticles, ranging in size from 70 to 90 nm and with a purity exceeding 97.9%, were incorporated into the formulation to further augment the material’s microstructural and functional performance.

Congestion test

For testing, three cylindrical specimens from each batch of Concret@FPS-CS were prepared, each measuring 35 mm in diameter and 40 mm in height. The samples were oven dried at 110 °C for 96 h to ensure complete moisture removal, after which their external surfaces were carefully polished using fine sandpaper. Following the drying process, the specimens were weighed and then subjected to a vacuum treatment at a pressure of 80–100 kPa for a duration of three days to eliminate any entrapped air within the pore structure. Following the vacuum process, the specimens were immersed in boiling water until fully submerged. The immersion process continued under negative pressure for about 30 h to ensure the removal of all air bubbles from the Concret@FPS-CS specimens and the heated water. After undergoing vacuum saturation, the Concret@FPS-CS samples were removed from the water tank and their weights were measured.

Hydration uptake test

The water absorption test was conducted in accordance with the procedures specified in BS 1881–122. The Concret@FPS-CS specimens were first weighed after their surfaces were saturated and subsequently wiped to remove excess surface moisture. The samples were then oven dried for 32 h, after which their dry weights were measured and recorded.

Drying shrinkage test

The prismatic specimens were dried along both radial and axial directions. Immediately after demoulding, the initial length (l₁) was measured, ensuring that any residual moisture on the gauge caps was completely removed to avoid measurement inaccuracies. Subsequent changes in length were monitored using a precision length comparator with a resolution of 0.003 mm. The measurements were systematically recorded over a 60 day period, starting on the 5th day and continued at regular intervals up to 60 days.

Results and discussion

The synthesis procedure for FPS-CS is illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, FPS nanofibers were prepared through the concurrent hydrolysis and condensation of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and triphenyl phosphate (TPP), serving as the silicon and phosphorus precursors, respectively. Within this nanocomposite framework, the FPS nanofibers function as the foundational scaffold, characterized by surface rich hydroxyl groups specifically HO–Si and HO–P rendering them highly suitable for subsequent chemical modification. These reactive groups facilitate the effective surface functionalization of FPS with chitosan, leading to the formation of FPS-CS. The FPS fibers also act as nucleation centers, promoting uniform chitosan grafting along their outer surfaces.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, a widely accepted method for assessing crystallinity and crystallite size, was utilized to characterize the FPS-CS composite. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the diffraction peaks of FPS-CS closely aligned with those of pure FPS, confirming the retention of its crystalline structure. Characteristic bands associated with chitosan (CS) were identified in the 480–1290 cm⁻1 region, corresponding to asymmetric stretching vibrations of C–C and C–N bonds. Comparative FT-IR spectra of FPS and FPS-CS (Fig. 3) revealed distinct absorption bands within the 775–1210 cm⁻1 range for the FPS-CS sample, attributed primarily to FPS components. However, one of these bands was obscured due to spectral overlap. In the infrared spectrum of unmodified FPS, four prominent peaks were observed at 504, 742, 912, and 1099 cm⁻1, which correspond to the vibrational modes of (P–O–P), (Si–O–Si), (P–O–Si), and (Si–OH or P–OH), respectively.

Figure 4 presents the FESEM and TEM images of FPS and FPS-CS. As shown in Figs. 4a and 4c, the FPS sample exhibited barrier-like structures with uniform dimensions, featuring dendrimer filaments approximately 50–60 nm thick that formed a three-dimensional network. These filaments provided access to the exterior layer. The FESEM and TEM images of CS-FPS revealed that the morphology of FPS remained unchanged after modification (Figs. 4b and 4 d).

Mesoporous based sorbents often experience a loss in surface integrity, void volume, and diameter during grafting, as large organic molecules occupy their channels. This obstruction hinders mass transfer within the material after modification and diminishes adsorption capacity. To address this challenge, we investigated FPS as a support due to its highly accessible surface area resulting from its fibrous structure. We then analyzed the changes in its textural properties after organic grafting. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of FPS-CS showed a distinct type IV curve (Fig. 5), consistent with previous reports on conventional fibrous silica spheres. The structural characteristics of CS based on FPS are summarized in Table 5. The CS particles did not completely fill the FPS fibrous structure, preserving the void volume and filament surface of the silica spheres in FPS-CS. As a result, the fibrous architecture of FPS provided improved compatibility for the components, including the FPS-CS particles.

Thermal stability analysis of the FPS and FPS–CS nanocomposites was performed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as shown in Fig. 6. The total weight loss for FPS–CS was approximately 27%, occurring in distinct steps that correspond to the removal of adsorbed water, the degradation of grafted chitosan, and the residual silica stability. An initial weight loss of about 3% in the temperature range of 50–200 °C is attributed to the evaporation of physically adsorbed and hydrogen-bonded water molecules on the fibrous silica surface. A more pronounced weight loss of 24%, observed between 250–400 °C, is assigned to the decomposition of chitosan chains covalently bound to the FPS surface. A minor mass loss above 600 °C is associated with the condensation of residual silanol and phosphate hydroxyl groups. This multi step degradation profile confirms the successful functionalization of FPS with chitosan and demonstrates the thermal stability of the FPS–CS structure up to ~ 250 °C, indicating its suitability for use in cementitious systems that undergo ambient or moderately elevated curing temperatures38.

The hydration kinetics of cement pastes containing varying amounts of FPS-CS were evaluated over a five-day period using isothermal calorimetry. Figure 7a displays the corresponding heat flow behavior and cumulative heat release characteristics. In contrast to the control paste, which exhibited the fastest hydration rate and the highest exothermic peak, the addition of FPS-CS resulted in a progressive reduction of the hydration rate and a delay in the peak heat release as the polymer content increased. This retardation effect is primarily caused by the high concentration of DFNS-CS, which accumulate within the capillary pores and adsorb onto nascent cement gel particles’ surfaces. This physical barrier impedes the nucleation and growth of hydration products. (Fig. 7b).

Workability is a critical property for repair mortars, as it directly influences their ease of application in practical construction settings. Figure 8 presents the slump values and apparent densities of polymer modified cement mortars. According to the Chinese standard JC/T 2381–2016, a minimum slump of 30 mm is required for repair mortars to ensure adequate flow. As illustrated in Fig. 8a, an increase in the polymer to cement (p/c) ratio led to a corresponding rise in slump values. The slump value exceeded the specified threshold when the polymer-to-cement (p/c) ratio surpassed 7%, mainly attributed to the aeration effect induced by FPS-CS. During mixing, FPS-CS facilitates the formation of numerous fine air bubbles, resulting in a "rolling ball effect" that enhances the mixture’s fluidity. This aeration delays both cement setting and hydration, thereby further improving the mortar’s overall workability. Figure 8b demonstrates that increasing the FPS-CS content led to a progressive reduction in the bulk density of the cementitious matrix. This trend can be explained by the reduced intrinsic density of FPS-CS in comparison to conventional cement slurry, along with the inclusion of air voids formed during mixing. A clear inverse relationship was observed between slump and apparent density, with both contributing positively to enhanced workability.

Figure 9 illustrates the performance of CS modified cement mortars incorporating different FPS-CS contents, with a focus on their mechanical properties. Across all curing durations 5, 10, and 30 days the inclusion of FPS-CS was generally associated with a reduction in compressive strength. A clear inverse relationship was observed between the polymer to cement (p/c) ratio and compressive strength at each curing stage. Several factors contribute to this trend: firstly, the presence of FPS-CS retards the cement hydration process, limiting early strength development; secondly, the resins embedded in the mortar matrix require extended curing time, and insufficiently cured resins fail to contribute effectively to mechanical strength; thirdly, the cured FPS-CS exhibits a lower elastic modulus than the crystalline hydration products of cement, diminishing its load-bearing capacity. However, continued hydration over time resulted in the formation of alkaline by products such as calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)₂], which may have promoted secondary curing reactions in the epoxy components. This chemical interaction could account for the modest improvements observed in both compressive and flexural strength. Mortars containing FPS-CS achieved compressive strengths comparable to those of the control, indicating that the negative effects of polymer incorporation diminished with prolonged curing, after 30 days. Since the curing of FPS-CS was nearly complete by day 10, the strength variation between the 10-day and 30-day specimens was minimal. As a result, the impact of FPS-CS on the mortar’s mechanical strength at later curing stages was insignificant.

Figure 10a displays the flexural strength of cement mortars incorporating different amounts of FPS-CS. In the early stages of curing, higher FPS-CS concentrations were associated with reduced flexural strength. This reduction is primarily attributed to the presence of uncured resin within the matrix, which delayed cement hydration and hindered early strength development. A lower polymer to cement (p/c) ratio was found to be more favorable for long term mechanical performance, as it minimized interference with hydration and allowed for better integration of the polymer network. By the 10th day of curing, a well developed cross linked polymer structure had formed, enabling the modified mortars to reach flexural strength values comparable to those of conventional mixes typically ranging between 7.8 and 8.7 MPa. As curing continued, the gap in strength between the polymer and the control modified specimens reduced, and the mortar with 8% FPS-CS exhibited superior flexural performance at the 30 day mark. However, further increases in FPS-CS content to 10% and 12% led to a decline in flexural performance. This can be attributed to the presence of excess, unreacted polymer material trapped within the matrix, which failed to participate in mechanical reinforcement and instead disrupted the structural cohesion. The incorporation of FPS-CS also resulted in adecreased cement to fiber ratio, indicating improved toughness. This enhancement is ascribed to the polymer’s bridging and filling capabilities, its intrinsic flexibility, and its strong interfacial adhesion. Nevertheless, achieving optimal mechanical behavior depends on a balanced dosage: insufficient FPS-CS content hinders network formation, while excessive amounts promote agglomeration and create overly dense polymeric layers, adversely affecting matrix integrity (Fig. 10b).

The interfacial flexural strength of cementitious composites is largely governed by the nature and strength of interfacial interactions such as covalent bonding, van der Waals forces, and ionic attractions between the adhesive matrix and the substrate. As shown in Fig. 11, the addition of FPS-CS markedly improved the interfacial flexural strength of the CS modified cement mortar. This improvement is attributed to the strong adhesion facilitated by the functional groups present in FPS-CS, which promote effective bonding at the mortar substrate interface. With increasing polymer to cement (p/c) ratios, interfacial flexural strength initially increased, reflecting improved interfacial cohesion, and eventually plateaued, indicating a saturation point beyond which additional polymer content offered no further mechanical benefit. Following 30 days of curing, the specimen with 8% FPS-CS reached its peak interfacial flexural strength, surpassing the blank mortar. The failure plane of the unmodified mortar exhibited a smooth appearance, indicative of weak interfacial bonding. There by confirming enhanced interfacial bonding and superior mechanical integration with the substrate.

Figure 12 depicts the strength characteristics of cement mortars incorporating polymers after immersion in 9% NaCl and 9% Na₂SO₄ solutions. At the initial stages of chemical exposure, all specimens showed an improvement in both compressive and flexural strengths. However, a significant decline in mechanical performance was observed with prolonged immersion. The polymer modified mortars reached peak strength values after 10 days of exposure, likely due to continued hydration and initial pore filling effects induced by early stage chemical reactions. The durability of repair mortars in corrosive environments is closely linked to the stability of cement hydration products. The ingress of sulfate and chloride ions progressively disrupts the microstructure of the mortar by initiating secondary chemical reactions. These ions interact with Ca(OH)₂ and other hydration products, leading to the formation of expansive compounds like ettringite, calcium oxychloride hydrate, and additional gypsum. The volumetric increase associated with these reaction products initially densifies the mortar matrix. However, as the reactions persist, the internal expansion generates stresses that exceed the tensile capacity of the mortar, leading to microcrack formation and structural degradation. Notably, the inclusion of FPS-CS greatly increased the mortar’s resistance to degradation in polymer-modified cement systems. The continuous chitosan coating over the FPS network effectively sealed internal pores and capillaries, serving as a physical barrier that limited the ingress of aggressive ions. This reduction in ion penetration mitigated the development of harmful compounds and significantly strengthened the mortar’s ability to resist sulfate and chloride-induced damage.

Since the internal porous network of cement mortars is heavily influenced by the chitosan (CS) content and the incorporation of fillers, water absorption is regarded as a key indicator for evaluating these microstructural alterations (Fig. 13). The introduction of FPS-CS into the mortar matrix led to the formation of numerous microbubbles during mixing, which increased the overall porosity and consequently elevated water absorption levels. However, at higher FPS-CS dosages, the nanocomposite effectively filled the internal voids, offsetting the porosity caused by entrained air. This pore-filling behavior of FPS-CS ultimately contributed to a reduction in water absorption, as the densified microstructure limited pathways for moisture ingress. Thus, the balance between bubble formation and void filling by FPS-CS plays a critical role in determining the water absorption characteristics of the modified mortar.

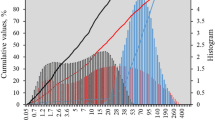

Micropores in cementitious materials are commonly classified into four categories based on their diameters and their impact on mechanical performance: moderately detrimental, non-detrimental, detrimental, and highly detrimental pores. The inclusion of FPS-CS in the mortar composition led to a notable reduction in the proportion of harmful pores, while simultaneously increasing the percentage of non detrimental pores. (Fig. 14) This shift indicates a refinement of the pore structure, contributing to improved durability and mechanical stability. Remarkably, replacing 9% of the conventional sand by FPS-CS produced a denser and more uniform matrix, lowering the average pore diameter to about 16 nm. This reduction in pore size further confirms the role of FPS-CS in promoting a denser microstructure with enhanced resistance to external stressors and environmental degradation.

Figure 15 highlights the effect of varying weight ratios of FPS and FPS-CS on the porosity of concrete specimens. Among all the specimens, FPS-CS showed the minimum porosity, achieving nearly a 23% decrease relative to the control sample. This significant decrease is primarily attributed to the improved hydration kinetics and superior pore-filling ability provided by the FPS-CS nanocomposite. By day 10, the measured porosities for FPS, FPS-CS, and the blank sample were 42%, 37%, and 49%, respectively, indicating the effectiveness of FPS-CS in densifying the cement matrix. The observed porosity reduction is likely due to the uniform dispersion and accumulation of FPS-CS particles, which effectively occupied void spaces and refined the pore network. Moreover, as the hydration process progressed into the capillary transport dominated phase, the interfacial transition zones between FPS/FPS-CS and the cement paste facilitated enhanced water mobility. This increased water diffusivity likely supported further hydration reactions, contributing to a denser microstructure and reduced total porosity. The control concrete sample showed large voids and interconnected cavities, whereas the addition of FPS and FPS-CS enhanced the microstructure by reducing void size and number, strengthening the matrix of cementitious material, enhancing the bond between filler components, and ultimately increasing strength.

Drying shrinkage in concrete refers to the volumetric contraction that takes place as moisture progressively evaporates from the cementitious matrix, which can ultimately lead to cracking and a gradual deterioration of structural integrity. This phenomenon is particularly critical in cementitious materials, where dimensional changes can compromise long term performance. The cement pastes incorporating FPS and FPS-CS exhibit viscoelastic behavior, suggesting that shrinkage is governed by both viscous flow and elastic deformation mechanisms. Figure 16 presents the drying shrinkage behavior of concrete samples prepared with varying weight ratios of FPS and FPS-CS. As expected, shrinkage progressively increased with time across all formulations. However, the control sample, lacking FPS or FPS-CS, demonstrated the highest shrinkage due to greater moisture loss. The inclusion of FPS and FPS-CS significantly mitigated shrinkage, indicating their beneficial role in enhancing dimensional stability. This shrinkage reduction can be attributed to the ability of FPS and FPS-CS to absorb tensile energy generated during the drying process. At the interface with the cement matrix, these nanocomposites act as energy-dissipating agents, reducing internal stresses and, consequently, the risk of cracking. Furthermore, their uniform dispersion promotes the nucleation of hydration products around their surfaces, leading to a denser and more resilient microstructure. Overall, the integration of FPS and FPS-CS contributes to superior shrinkage resistance and mechanical durability in polymer modified cement composites.

Figure 17a presents a comparison of weight loss between FPS and FPS-CS, emphasizing the positive impact of FPS based polymers on enhancing frost resistance. The findings reveal that FPS-CS experienced considerably less weight loss than both the blank samples and FPS, suggesting superior resistance to frost induced deterioration. Concrete samples containing FPS and FPS-CS showed improved resistance under freeze–thaw conditions relative to those without this additive. As shown in Fig. 17b, the compressive strength of the concrete specimens varied after undergoing freeze thaw cycles. Notably, the sample containing 0.9% FPS-CS exhibited the best performance, retaining the most compressive strength even after 250 freeze thaw cycles. This demonstrates that FPS-CS significantly enhances the concrete’s resistance to freeze thaw damage, ensuring better durability and preserving its structural integrity under extreme temperature conditions.

The concrete’s resistance to acid was evaluated by exposing samples to a 4% sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) solution, focusing on the material’s durability against sulfate attack. Concrete specimens containing FPS-CS exhibited notable improvement in acid resistance. After being exposed to the acidic environment for 15 weeks, the FPS-CS modified concrete showed the least weight loss, approximately 1.0%, when compared to the other samples. As illustrated in Fig. 18a, the control sample underwent the greatest weight loss, whereas the FPS-modified concrete experienced a greater loss than the FPS-CS modified concrete. Further analysis was conducted through compressive strength testing of the acid exposed samples at intervals of 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 weeks. Figure 18b compares the compressive strength of these samples to that of the control specimen. Notably, only the concrete with FPS-CS demonstrated improved compressive strength following six weeks of sulfuric acid exposure. This enhancement is attributed to the filling of voids in the concrete matrix by reaction products from the acid interaction. By the ninth week, the FPS-CS modified concrete showed an increase in strength, while the strength of the remaining samples began to decline. Following 15 weeks, all the concrete samples exhibited a more substantial decrease in compressive strength compared to the FPS-CS modified concrete, emphasizing the superior acid resistance of the FPS-CS composite material. The FPS–CS nanocomposite developed in this study integrates two sustainability oriented strategies: (i) valorization of shrimp shell waste as a renewable and biodegradable source of chitosan, and (ii) use of fibrous phosphosilicate synthesized via a scalable sol–gel process. The utilization of shrimp shell waste not only provides a low-cost biopolymer but also contributes to reducing environmental burden by diverting significant quantities of organic waste from disposal streams. The FPS synthesis route, based on low toxicity silica and phosphate precursors, is compatible with existing nanoparticle production lines. Furthermore, the covalent grafting of chitosan onto FPS is performed under moderate temperatures and ambient pressures, allowing straightforward process adaptation for larger scale manufacturing. Considering the abundance of raw materials and the process simplicity, FPS–CS has the potential for cost effective scale up and industrial application in the production of green, durable cement-based composites.

Conclusions

This study presents a facile and sustainable approach for covalently grafting shrimp-shell-derived chitosan (CS) onto fibrous phosphosilicate (FPS), producing a novel FPS–CS nanocomposite. The effects of FPS–CS on hydration behavior, workability, mechanical properties, and durability of cement mortars were systematically evaluated. The key conclusions are as follows:

-

Microstructural refinement and porosity reduction – Incorporation of FPS–CS led to a substantial reduction in total porosity, with the optimal dosage (8% p/c) achieving ~ 23% lower porosity compared to the control. Pore size distribution analysis confirmed a higher proportion of non-detrimental pores and a significant decrease in harmful pores, resulting in a denser and more durable cement matrix.

-

Durability improvements under aggressive conditions – FPS–CS modified mortars exhibited superior resistance to chloride and sulfate attack, retaining 18–22% higher compressive strength than the control after prolonged immersion. In freeze thaw durability tests, FPS–CS maintained over 90% of initial compressive strength after 250 cycles, compared to only 71% for the control. Acid resistance was also markedly enhanced, with FPS–CS modified concrete showing only ~ 1.0% mass loss after 15 weeks in 4% H₂SO₄, versus 4.5% for the control.

-

Innovation and practical significance – This work introduces, for the first time, a shrimp shell derived chitosan functionalized fibrous phosphosilicate (FPS–CS) nanocomposite as a multifunctional additive in cementitious systems. The FPS–CS not only improved workability (slump increase of up to ~ 35% compared to the minimum standard) and reduced paste density by up to 7%, but also significantly enhanced durability against multiple degradation mechanisms. The optimal 8% p/c ratio provided balanced mechanical performance, microstructural densification, and environmental resistance, demonstrating both the scientific novelty and the practical applicability of this sustainable, waste-derived material for green and durable construction.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FPS:

-

Fibrous phosphosilicate

- CS:

-

Chitosan

- FC:

-

Fine concrete

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- FTIR:

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- BET:

-

Brunauer–emmett–teller

- CPB:

-

Cetylpyridinium bromide

- AFM:

-

Atomic force microscopy

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

References

Kareem, M. A., Raheem, A. A., Oriola, K. O. & Abdulwahab, R. A review on application of oil palm shell as aggregate in concrete -Towards realising a pollution-free environment and sustainable concrete. Environ. Chall. 8, 100531 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Damage-tolerant material design motif derivedfrom asymmetrical rotation. Nat. Commun. 13, 1289 (2022).

Mydin, M. A. The effect of raw mesocarp fibre inclusion on the durability properties of lightweight foamedConcrete. J. Sci. Technol. Dev. 38, 59–66 (2021).

Raj, A., Sathyan, D. & Mini, K. M. Physical and functional characteristics of foam concrete: A review. Construct. Build. Mater. 221, 787–799 (2019).

Mydin, M. A. O., Nawi, M. N. M., Odeh, R. A. & Salameh, A. A. Durability properties of lightweight foamed concretereinforced with lignocellulosic fibers. Material 15, 4259 (2022).

Mohd Zamzani, N., Mydin, O. M. A. & Ghani, A. Mathematical regression models for prediction of durability propertiesof foamed concrete with the inclusion of coir fibre. Int. J. Eng. Adv. 8, 3353–3358 (2019).

Jones, M. R., Ozlutas, K. & Zheng, L. Stability and instability of foamed concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 68, 542–549 (2016).

Nensok, M. H., Mydin, M. A. & Awang, H. J. Investigation of thermal, mechanical and transport properties of ultralightweight foamed concrete (ULFC) strengthened with alkali treated banana fibre. J. Adv Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 86(123), 139 (2021).

Al-kahtani, M. S. M., Zhu, H., Ibrahim, Y. E., Haruna, S. I. & Al-qahtani, S. S. M. Study on the mechanical properties ofPolyurethane-cement mortar containing nanosilica: RSM and machine learning approach. Appl. Sci. 13, 13348 (2023).

Othman, R. et al. Relation between density and compressive strength of foamed concrete. Material 14, 2967 (2021).

Mydin, M. A. O. et al. Influence of polyformaldehyde monofilament fiber on the engineering properties of foamed concrete. Material 15, 8984 (2022).

Bokhari, A., Yusup, S., Faridi, J. A. & Kamil, R. N. M. Blending study of palm oil methyl esters with rubber seed oilmethyl esters to improve biodiesel blending properties. Chem Eng. Trans. 37(571), 576 (2014).

Arshad, S. et al. Assessing the potential of green CdO2 nano-catalyst for the synthesis of biodiesel usingnon-edible seed oil of malabar ebony. Fuel 333, 126492 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Co-pyrolysis of lychee and plastic waste as a source of bioenergy through kinetic study and thermodynamic analysis. Energy 256, 124678 (2022).

G¨okçe, H. S., Hatungimana, D. & Ramyar, K. Effect of fly ash and silica fume on hardened properties of foamedconcrete. Build. Mater. 194(1), 1 (2019).

Zahmatkesh, S., Ni, B.-J., Klemeˇs, J. J., Bokhari, A. & Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Carbon quantum dots-Ag nanoparticlemembrane for preventing emerging contaminants in oil produced water. J. Water Proc. Eng. 50, 103309 (2022).

Zahedifar, M., Es-haghi, A., Zhiani, R. & Sadeghzadeh, S. M. Synthesis of benzimidazolones by immobilized goldnanoparticles on chitosan extracted from shrimp shells supported on fibrous phosphosilicate. RSC Adv. 9, 6494–6501 (2019).

Brinklov, S., Kalko, E. K. V. & Surlykke, A. Intense echolocation calls from two ‘whispering’ bats, artibeus jamaicensisand macrophyllum macrophyllum (Phyllostomidae). J. Exp. Biol. 212, 11–20 (2009).

Jen, P. H. S. & Wu, C. H. Echo duration selectivity of the bat varies with pulse–echo amplitude difference. NeuroReport 19, 373–377 (2008).

AnChiu, C., Xian, W. & Moss, C. F. Flying in silence: Echolocating bats cease vocalizing to avoid sonar jamming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 13116–13121 (2008).

Moss, C. F. & Sinha, S. R. Neurobiology of echolocation in bats. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13, 751–758 (2003).

Teeling, E. C. et al. Molecular phylogeny for BatsIlluminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science 307, 580–584 (2005).

Shaabani, A., Boroujeni, M. B. & Laeini, M. S. Copper(ii) supported on magnetic chitosan: A green nanocatalyst for thesynthesis of 2,4,6-triaryl pyridines by C–N bond cleavage of benzylamines. Rsc. Adv. 6, 27706–27713 (2016).

Carlsen, L., Kenesova, O. A. & Batyrbekova, S. E. A preliminary assessment of the potential environmental and humanhealth impact of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine as a result of space activities. Chemosphere 67, 1108–1116 (2007).

Neubaum, D. J., Wilson, K. R. & O’shea, T. J. Urban maternity‐roost selection by big brown bats in Colorado. J. Wildlife Manage. 71, 728–736 (2007).

DeLong, C. M., Bragg, R. & Simmons, J. A. Evidence for spatial representation of object shape by echolocating bats(Eptesicus fuscus). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 4582–4598 (2008).

Kingston, T. Research priorities for bat conservation in Southeast Asia: A consensus approach. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 471–484 (2010).

Chiu, C. & Moss, C. F. The role of the external ear in vertical sound localization in the free flying bat, Eptesicus fuscus. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121, 2227–2235 (2007).

Zorina, Z. A. & Obozova, T. A. Obozova. Zool. Zhurnal 90, 784–802 (2011).

Zhao, L., Wang, M., Zhang, L. & Sadeghzadeh, S. M. Impact of chitosan extracted from shrimp shells on the shrinkageand mechanical properties of cement-based composites using dendritic fibrous nanosilica. Heliyon 10, e31576 (2024).

Smirnov, A. V., Kots, P. A., Panteleyev, M. A. & Ivanova, I. I. Mechanistic study of 1,1-dimethylhydrazine transformation overPt/SiO2 catalyst. RSC Adv. 8, 36970–36979 (2018).

Cao, Q. L., Wu, W. T., Liao, W. H., Feng, F. & Massoudi, M. Effects of temperature on the flow and heat transfer in gel fuels:A numerical study. Energies 13, 821 (2020).

Pepperberg, I. M. Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus) numerical abilities: addition and further experiments on a zero-like concept. J. Comp. Psychol. 120, 1 (2006).

Brucks, D. & Bayern, A. M. P. Parrots voluntarily help each other to obtain food rewards. Curr. Biol. 30, 292–297 (2020).

Pepperberg, I. M., Schachner, A. & Brady, T. F. Spontaneous motor entrainment to music in multiple vocal mimickingspecies. Curr. Biol. 19, 831–836 (2009).

Liberman, M.A., Act. Flow Combust. Control. 127 317–341 (2014).

Zhiani, R., Khoobi, M. & Sadeghzadeh, S. M. Phosphosilicate nanosheets for supported palladium nanoparticles as anovel nanocatalyst. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 275, 76–86 (2019).

Wang, Y. S., Lin, R. & Wang, X. Y. Insights on solid CO2 mixing method for hybrid alkaline cement (HAC): Performance,sustainability, and experimental system improvement. Cement Concr. Compos. 161, 106096s (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qisong Zhao: Investigation, Resources, Data Curation; Rahele Zhiani: Writing—Original Draft;

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

There are no conflicts to declare.

Consent for publication

There are no conflicts to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Q., Zhiani, R. Chitosan derived from shrimp shells functionalizes dendritic fibrous nanosilica to improve concrete’s early properties and durability. Sci Rep 15, 43219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27216-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27216-1