Abstract

The use of a plough is characterized by the presence of a turning moment acting in a clockwise direction. When placing the plough resistance center to the left of the tractor’s longitudinal symmetry axis, it becomes possible to use the plough with one landside placed on its last bottom. The article presents a new analytical dependence that allows determining the design and technological parameters of the plow using the transverse displacement of the center of resistance to the left of the tractor’s longitudinal axis of symmetry. Studies have shown that using a plough with one landside instead of five does not affect the ploughing depth and the operating width. At the statistical significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis about the equality of the mean values and variances of these parameters’ oscillations is not rejected. The normalized correlation functions and spectral densities of these processes’ oscillations are approximately the same. Using a plough with one landside instead of five leads to a 10.3% decrease in draft resistance, accompanied by a 10% decrease in specific fuel consumption. This study fills a gap in the practical operation of plows, aimed at reducing their draft resistance, which is key in reducing fuel consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The plough, as it is known, is designed for moldboard soil cultivation. The minimum ploughing depth is 0.18–0.20 m1. At the same time, researchers are investigating the feasibility of performing this technological operation at depths of 0.12 m and even less (down to 0.08 m)2. The maximum value of this parameter is typically limited to the arable layer depth, which is equal to 0.3 m3. At the same time, farmers are attempting to carry out this operation at depths of 0.35 m and greater4.

It is essential that the same plough, in the same soil conditions and with the same driving mode, working with different tractors, can have different draft resistances. This is explained by the fact that the design width of the plough, as a rule, does not exceed the width of the tractor’s chassis. Because of this, the resistance center of the former is most often to the right (when viewed from behind) of the symmetry longitudinal axis of the latter. As a result, a moment arises that tends to turn the plough clockwise5,6,7,8,9.

When the plough’s operating width exceeds the tractor’s chassis width, a left-side transverse shift of the resistance center of the former relative to the symmetry longitudinal axis of the latter may occur10. With this unit design, a turning moment also acts on the plough, but its value is less. In both cases, the action of this moment is impeded by the landsides of the plough’s bottoms11,12,13. This suggests that their design parameters, including width and length, must be carefully justified.

However, instead of solving this problem, researchers often try to replace the plough’s landsides with other devices13,14,15. In this case, the rolling friction force is used instead of the sliding friction force. This result is achieved using various cylindrical disk devices instead of landsides16,17. As a result, this leads to a significant complication of the plough design, the increase in the cost of which can almost completely neutralize the effectiveness of replacing the landsides with other devices. At present, we have not found any refutations of this assumption in the literature.

There have been known attempts to create ploughs without landsides18. Their role is performed by additional ploughshares that are installed. However, in addition to complicating the design of the plough bottom, such a solution requires a special cycle of theoretical and experimental research.

The conducted studies have established that the last bottom of a conventional plough has the most loaded landside19, which is a logical fact. In contrast, the work notes that the first bottom of the plough has the most loaded landside20. In our opinion, this occurs when the operating width of this bottom is greater than the operating width of the others. In this case, the first bottom of the plough has a larger operating width than the other bottoms. This result is undesirable, as it leads to increased energy consumption due to the friction between the landslide and the soil21.

The article22 proposes analytical dependencies for calculating the length and thickness of the plough’s bottom landside. Particularly noteworthy is that in the proposed equation, the length of the landside (\(\:{L}_{ls}\)) is directly proportional to its width (\(\:b\)). This means that an increase in the \(\:b\) parameter causes a corresponding increase in the value of the \(\:{L}_{ls}\) parameter. In our opinion, such a ratio of these landslide design parameters is illogical. Moreover, the authors of this scientific work a priori (i.e., without proof) propose that the landside width (b) equals one-third of the plough’s bottom share width.

The test results of ploughs with two types of mouldboards of bottoms equipped with field landsides of different lengths are known23. In the article24, the values of this parameter were equal to 150 and 300 mm. At the same time, the obvious fact was established that with a greater landslide length, the draft resistance of the plough is higher. In this study, there are no practical recommendations concerning selecting the required value of either the landslide width or its length.

Article25 examines the forces acting on the plough bottom’s landslide. However, firstly, the equations proposed by the authors are very complex due to the large number of parameters they include. Secondly, these equations do not allow for choosing the landside parameters’ optimal (or rational) values.

We have emphasized above that with the left-hand transverse displacement of the plough, its traction resistance decreases. This result is achieved by reducing the friction force of the landsides against the furrow wall due to the decrease in the load acting on them. As a result, removing all the landsides except the one installed on the last of the plough’s bottom becomes possible. However, for this, it is necessary to have a method for substantiating the design parameters of this landside. First of all, this concerns its width and length26.

As already emphasized above, no substantiated results of this problem solution were found in publications. In this regard, the aim of this article is: (1) to develop an analytical dependence for the substantiated choice of the width and length of the plough’s landside under the condition of a left-side transverse displacement of its resistance center; (2) to conduct comparative tests of the plough with a landside installed on its last body.

The stated objective determines the further direction of research, the essence of which is to achieve the possibility of reducing the plough draft resistance while maintaining the uniformity of its movement in terms of ploughing depth and operating width. Ultimately, the goal is to reduce fuel consumption per tilled area during ploughing.

Theoretical premises

With a right-side transverse shift of the plough’s resistance center (point \(\:{D}_{1}\), Fig. 1), the tractor’s traction force (\(\:{T}_{1}\)) is decomposed into two components: \(\:{T}_{1v}\)and \(\:{T}_{1r}\)10. The first component moves the plough forward. The second component presses the plough against the furrow wall. The load on the landsides increases, which leads to an increase in the plough’s traction resistance27,28.

With a left-side transverse shift of the plough resistance center (point \(\:{D}_{2}\), Fig. 1), the tractor traction force (\(\:{T}_{2}\)) is also decomposed into two components: \(\:{T}_{2v}\) and \(\:{T}_{2r\:}\). But if the first of them, as in the previous case, moves the plough, the second tends to push it away from the furrow wall. As a result, the plough traction resistance decreases. Since this reduces the load on the landsides, it becomes possible to leave only the one that is on the last bottom.

In this case, the load on this landside (\(\:N\)) can be represented through the total force of resistance to the movement of the soil by the plough in the transverse direction:

where \(\:N\) – load on landside, N; \(\:{\Sigma\:}{P}_{x}\) – total soil resistance in the transverse direction, N.

The field board creates pressure on the soil, which must be less than the maximum permissible pressure:

where \(\:b,l\) ‒ width and length of the landside, respectively, m; \(\:\sigma\:\) – pressure on soil, Pa; \(\:{\sigma\:}_{o}\) – maximum permissible pressure on soil, Pa.

The total force \(\:{\Sigma\:}{P}_{x}\) can be represented as follows10:

In Eq. (3), the following notations are adopted: \(\:\gamma\:\) is the inclination angle of the plough bottom share to the furrow wall, grad; \(\:\phi\:\) is the angle of internal friction in the soil, grad; \(\:{K}_{s}\) is the coefficient of plough specific resistance, kN∙m− 2; \(\:{B}_{p}\) is the width of the plough, m; \(\:h\) is the ploughing depth, m.

The joint solution of Eqs. (2) and (3) leads to the following result:

Inequality (4) allows for a reasonable choice of the landside’s width (\(\:b\)) and length (\(\:l\)) values, taking into account their dependence on several design and technological parameters.

Materials and methods

The physical object of the research was a ploughing unit consisting of a KhTZ-16,131 tractor (Ukraine) and a five-bottom plough PLN-5–35 (Fig. 2). This plough is manufactured by AGRO FAMILY UKRAINE (Odesa region, Ukraine). In terms of working width, draft resistance, and hitch dimensions, the PLN-5–35 is optimally matched with the KhTZ-16,131 tractor, which is widely used throughout Ukraine.

This tractor is equipped with 16.9R38 tires and has a track width of 2.1 m. Five plough bottoms, each with an operating width of 0.35 m, form an operating width of the entire machine equal to 1.75 m. When operating with such a plough, the tractor’s right-side wheels move in the furrow. The plough resistance center is shifted to the left of the tractor’s longitudinal axis. As noted above, this fact creates the potential possibility of removing all landsides except the last one (Fig. 3).

When determining its design parameters from inequality (4), the value of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) parameter was changed within the range of 50–65 kN∙m− 2. These values of the plough specific resistance are typical for most soil-climatic zones of Ukraine, in one of which the research of this ploughing machine-tractor unit was conducted.

The value of the \(\:\gamma\:\) angle in theoretical calculations varied from 30 to 50°, and the \(\:\phi\:\) angle from 20 to 40°. The value of the \(\:{\sigma\:}_{o}\) parameter was equal to 450 kPa28. In general, the nomenclature of parameters used in theoretical calculations of the landside’s geometric dimensions is given in Table 1.

The ploughing unit was used in two variants for conducting experimental studies. Variant 1 ‒ tractor KhTZ-16,131 with a plough PLN-5–35, equipped with one landside (Fig. 3). Its dimensions were as follows: b = 0.17 m, \(\:l\) = 0.30 m. Variant 2 ‒ the same tractor with the same plough, equipped with all (i.e., five) landsides.

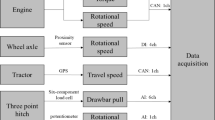

During the field studies of both variants of the ploughing unit, the following parameters were measured in two repetitions: (i) ploughing depth (\(\:h,\:\text{m}\)); (ii) operating width (\(\:{B}_{p},\:\text{m}\)); (iii) plough draught resistance (\(\:{P}_{p},\:\text{k}\text{N}\)); (iv) operating velocity (\(\:{V}_{p},\:\)m∙s− 1); (v) specific fuel consumption (\(\:{G}_{p}\), kg∙ha− 1).

The measurements of the specified parameters were carried out on sites, each 150 m long. The first 25 m of the site were used to accelerate the ploughing unit. The measured parameters were recorded on the next 100 m of the site. Both ploughing units moved on the same tractor gear. The PLN-5–35 plough with a design width of \(\:{B}_{p}\) = 1.75 m was adjusted to a ploughing depth of h = 0.25 m. The ploughing unit movement speed (\(\:{V}_{p}\)) was calculated using the formula \(\:{V}_{p}\) = 100∙t−1, where t is the time (s) for the ploughing unit to pass a site 100 m long.

It should be noted that, according to the preliminary research data, we have established that the processes of fluctuations in the depth and width of plowing, as well as the plough draft resistance, are stationary and, most importantly, ergodic. This fact gives the researcher the right to make only one repetition of the recording of the measured parameters. In the studies we conducted, as noted above, a two-fold repetition of the experiments was adopted. Thus, each of the plowing units passed 100 control meters in the forward direction and 100 m in the opposite direction. The total width of the processed soil strip on which the measurements were carried out was at least 3.5 m.

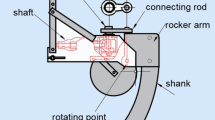

To measure the ploughing depth, a device (Fig. 4) with a built-in Arduino Uno (Italy) was used.

Before the measurement, the device was installed vertically with the long part of the support 2 in the field near the wall of the open furrow. The ultrasonic sensor HC-RS04 (China), mounted in the measuring unit 1 together with the Arduino UNO, recorded the distance L, which met the condition \(\:l=h=0\), where \(\:h\) is the ploughing depth. Then, the movable rod 3, together with the measuring unit 1, was freely lowered to a depth l until the rod touched the bottom of the furrow. The measuring unit 1 recorded a new value of the distance L, which met the new condition: \(\:l=h\). The number of ploughing depth measurements after each pass of the ploughing MTU was not less than 50. The measurement step of this parameter was 0.2 m. The measurement error of the ploughing depth by this device was ± 0.25 cm.

The devices and equipment, as well as the methodology for their use, are for measuring the \(\:{B}_{p},{P}_{p}\) parameters are described in detail in the article29. When measuring the ploughing unit operating width, its first pass was carried out along a straight line marked on the field with special markers (wooden pegs). As a result, an open furrow formed by the last plough bottom was obtained. In the transverse direction from the wall of this furrow, at a distance of 5 m with a step of 1 m, 50 pegs were installed.

During the plowing unit control movement, the tractor driver monitored the open furrow of the first pass. After completing the MTU working movement, the distance from the pegs to the wall of the furrow newly created by the plough was measured with a tape measure. The plough operating width mean value was calculated using the formula:

where \(\:{h}_{i}\) – distance from the i-th peg to the wall of the control furrow, m.

To measure the plough’s traction resistance, a strain gauge link was used, the measuring bridge of which consisted of four BF120-1AA foil sensors (Sensorcon, China), with a nominal value of 120 ± 1 Ω. The electrical signal from the strain gauge link was recorded in digital form on a microSD using Arduino Uno (Italy). The sampling rate of the recorded signal was 0.1 s, and the recording duration was at least 45 s.

To measure the hourly fuel consumption, two DFM 50AK (Bulgaria) sensors were used with a measurement error of no more than 1%30,31. The specific fuel consumption of the ploughing unit was determined from the equation:

where \(\:G\) – hourly fuel consumption, kg∙h− 1; \(\:{B}_{p}\) – plough operating width, m; \(\:V\) – ploughing unit velocity, m·s− 1.

Statistical data processing was carried out in the software environments Microsoft Excel and Mathcad 15.

Results and discussion

Theoretical analysis of inequality (4) shows that the higher the value of the plough’s specific traction resistance, the wider the landside should be (Fig. 5).

Such a result is quite logical. A larger value of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) parameter causes, as follows from Eq. (3), a larger value of the total force \(\:{\Sigma\:}{P}_{x}\). As a result, the plough pressure on the landside increases. To avoid reaching the maximum permissible soil compression (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{o}\)), the width of the landside (parameter \(\:b\)) should be increased.

Based on the analysis of inequality (4), the influence of the ploughing depth (\(\:h\)) and the plough width (\(\:{B}_{p}\)) on the landside’s width value is qualitatively the same as the influence of the \(\:{K}_{s}\) parameter considered above (Fig. 5). The influence of the soil friction angle (parameter \(\:\phi\:\)) on the parameter b has a diametrically opposite character: an increase in the value of the first causes an increase in the second (Fig. 6).

Since the friction angle of the soil is directly related to the friction coefficient (\(\:f\)), an increase in the value of the \(\:\phi\:\) parameter means an increase in the value of the \(\:f\) parameter.

Field studies of ploughing units were conducted under field conditions in southern Ukraine (Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Zaporizhzhia Raion, 47.838° N latitude, 35.138° E longitude). The characteristics of these conditions are presented in Table 2.

A comparison of ploughing variants showed the following. The ploughing depth for both plough setting variants was approximately the same (Table 3). The actual difference between the mean values of this parameter was 0.6 cm. This is less than the least significant difference (LSD05), which is equal to 0.81 cm. It follows that, at a 0.05 statistical significance level, the null hypothesis regarding the equality of the compared mean values is not rejected. In other words, replacing five landsides with one does not significantly affect the ploughing depth compared to the ploughing units.

The variability of the ploughing depth fluctuation processes for both plough variants is low. This is followed by comparing the correlation coefficients, the values of which are approximately equal (see Table 3) and do not exceed 10%32.

Moreover, the internal nature of ploughing depth fluctuations in both compared cases is also approximately the same. This result is confirmed by the nature of the change in the normalized correlation functions33 of ploughing depth variations (Fig. 7). The lengths of the correlation link for them differ little and are approximately 0.70–0.72 m. In Fig. 7, these are the abscissas at which the considered normalized correlation functions cross the zero mark. It should also be noted that there are practically no periodic components, such as the flow of these functions.

As for the frequency spectrum of ploughing depth fluctuations, they are practically the same for the compared processes. The spectrum of their variances, as determined by the analysis of normalized spectral densities (Fig. 8), is concentrated primarily in one range, specifically 0–15 m− 1.

The ploughing unit velocity in variant 1 was 2.36 m∙s− 1 and in variant 2 was 2.20 m∙s− 1 (see Table 3). In this case, the above frequency range is 0–33 rad·s− 1 or 0–5.25.25 Hz for the first variant of the unit and 0–30 rad·s− 1 or 0–4.78.78 Hz for the second. The null hypothesis about the equality of the compared variances of ploughing depth oscillations is not rejected. This is supported by the F-test value34, which is 6.76/6.26 = 1.08, and is less than the tabular value of 1.39.

The null hypothesis, which states that the mean values of the compared ploughing units’ operating widths are equal, is also not rejected at a statistical significance level of 0.05. The actual arithmetic difference of these parameters is 1.1 cm, which is less than LSD05 = 1.3 cm (Table 3).

The normalized correlation functions of the oscillations in the operating width of both units are practically identical (Fig. 9).

The correlation connection length of these functions is within 2.8–3.0 m. The correlation function of the oscillations of the plough operating width with five landsides (variant 2) shows the presence of a periodic component. However, it is challenging to determine the period of these oscillations. It is even more difficult to establish their generator. To resolve this issue, an additional study cycle is required. Approximately the same can be said about the correlation function of oscillations of the plough operating width equipped with one landside (variant 1).

Based on the analysis of the obtained data, the F-test actual value for the variances of the oscillations in the ploughing units’ operating width is 1.04. Since this is less than the tabular value of 1.39, the null hypothesis that these statistical indicators are equal is not rejected. Moreover, the spectrum of the compared variances is concentrated in the same range, i.e., 0–2.9 m− 1 (Fig. 10). Taking into account the ploughing MTUs’ velocity 2.20 and 2.36 m∙s− 1, this is 0–6.38.38 and 0–6.84 rad·s− 1 or 0–1.01.01 and 0–1.09.09 Hz, respectively.

The difference between the compared ploughing units is presented in their draft resistance. For a plough with one landside, it is 3.3 kN less. This difference exceeds LSD05, equal to 0.3 kN (see Table 3). This means the null hypothesis about the equality of the mean values of the compared ploughs’ draft resistances is rejected.

Setting the ploughing unit according to variant 1 ensures a decrease in the draft resistance of a plough equipped with one landside instead of five.

As for the variances of the plough draft resistance oscillations, the difference between them is insignificant and statistically random. This follows from the fact that the actual value of the F-test for the compared variances, equal to 1.24, is less than the tabulated value, equal to 1.39.

At the same time, the oscillations of the plough draft resistance with one landside (variant 1) are characterized by a lower frequency. The normalized correlation function of this process is equal to 0.95 m (Fig. 11). For the oscillations’ correlation function of the plough’s draft resistance with five landsides (variant 2), this value is greater and is 1.15 m.

From the behavior of the normalized spectral densities of the compared ploughs’ draft resistance oscillations, the unit, according to variant 1, has a somewhat narrower variance spectrum (Fig. 12). Moreover, in this case, the maximum of the normalized spectral density occurs at a frequency of approximately 3 s− 1. At the same time, according to variant 2, the maximum variance occurs at a higher frequency, equal to 6 s− 1, for the ploughing unit.

This is twice as much as in the previous option of ploughing unit adjustment. It follows from the above that equipping the plough with one landside ensures a decrease in its draft resistance while simultaneously reducing the oscillation frequency of this parameter. As a result, due to the reduction in the plough’s draft resistance, the specific fuel consumption of the ploughing unit adjusted according to variant 1 turned out to be 10% less (Table 3) than the specific fuel consumption of the unit adjusted according to variant 2.

Conclusions

An analytical dependence has been developed to determine the width and length of the plough’s landside, considering its design-technological parameters and attachment with a left-side transverse displacement of the resistance center relative to the tractor’s longitudinal symmetry axis. In theoretical terms, the significance of this dependency is determined by its ability to disclose the fundamental nature of the interrelationship between the geometrical and structural parameters of the plough’s landside and both the design characteristics of the implement and the physical–mechanical properties of the cultivated soil.

Using a plough with one landside instead of five does not affect the ploughing depth and its operating width. At the statistical significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis about the equality of the mean values and variances of these parameters’ oscillations is not rejected. The correlation functions and spectral densities of these processes’ oscillations are approximately the same.

Using a plough with one landside instead of five led to a decrease in its draft resistance. In the field experiment, it was 10.3%. As a result, this led to a 10% reduction in specific fuel consumption.

The obtained research results indicate the prospects of using a plough with one landside under the condition of a left-side transverse displacement of its resistance center relative to the tractor’s longitudinal symmetry axis. This study fills a gap in the practical operation of ploughs aimed at reducing their draft resistance. This is a key point in reducing fuel consumption by plowing units while maintaining the quality of soil cultivation.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bulgakov, V. et al. Analysis of the state and assessment of possible ways of preservation of soil fertility during its mechanical treatment. J. Ecol. Eng. 23 (4), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/146334 (2022).

Kurstjens, D. A. G. & Perdok, U. D. The selective soil covering mechanism of weed harrows on sandy soil. Soil. Tillage Res. 55, 193–206 (2000).

Williams, V. Soil Science with the Basics of Agriculture. (Lviv, 2009).

Kouwenhoven, J. K., Perdok, U. D., Boer, J. & Oomen, G. J. M. Soil management by shallow mouldboard ploughing in the Netherlands. Soil. Tillage Res. 65, 125–139 (2002).

Bulgakov, V. et al. Influence of tractor Hitch linkage system on plowing unit performance. Eng. Rural Dev. 523–532. https://doi.org/10.22616/ERDev.2023.22.TF111 (2023).

Pastor, J., Ilyes, S., Popa-Muller, I., Egyed-Faluvegu, F. & Farmos, R. Study of the dynamic equilibrium of the tractor-suspended plough. in Nemzetközi Gépészeti Konferencia–OGET. 391–394 (In Romania) (2023).

Sheng-li, Z. et al. A joint control method considering travel speed and slip for reducing energy consumption of Rear wheel independent drive electric tractor in ploughing. Energy. 263, 126008 (2023).

Simikić, M. et al. Influence of eccentric drawbar force on power delivery efficiency of a wheeled tractor. Turkish J. Agric. For. 36, 486–500 (2012).

Ryzhykh, N. E. Influence of the direction of the line of action of the traction force on the resistance of the plow. Polythematic Netw. Electron. Sci. J. Kuban State Agrar. Univ. 8, 1–8 (2004). (in Russian).

Bulgakov, V., Nadykto, V., Ivanovs, S. & Dukulis, I. Improving the performance of a ploughing tractor by means of an auxiliary carriage with motorized axle. J. Agric. Eng. 52, 9–16 (2021).

Guul-Simonsen, F., Jørgensen, M. H., Have, H. & Håkansson, I. Studies of plough design and ploughing relevant to conditions in Northern Europe. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil. Plant. Sci. 52, 57–77 (2002).

Ortopan, M. et al. Analyzing Site-Specific tractor draft force in different passes during plowing. Tech. Gaz. 31, 228–232 (2024).

Mansurov, M. T. TO the Calculation of the Parameters of the Attachments of the Front and Rear Parts of the Plow According to the Push-Pull System. in International Congress on Multidisciplinary Studies in Education and Applied Sciences. 8–13 (2022).

Bulakh, M. Freight wagon body design with increased load capacity. Sci. Rep. 15, 13189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97152-7 (2025).

Bulakh, M. Application of cold plasma to reduce the roughness of the working surface of a railway car center plate. Materials 17, 5437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17225437 (2024).

Dzuyba, O. Status of the issue and the ways of improvement of long-temperature flights. Tech. Serv. Agric. Transp. Syst. 11, 226–232 (2018).

Trubilin, E. I., Konovalov, V. I., Konovalov, S. I., Belousov, S. V. & Movchan, E. S. Theoretical justification of parameters of a plow cylindrical field board. Polythematic Online Sci. J. Kuban State Agrar. Univ. 137, 1–15 (2018).

Boykov, V. M., Startsev, S. V., Pavlov, A. V. & Nesterov, E. S. Results of experimental studies of the plow for coupling with drawbar category 3 tractors. Tractors Agric. Mach. 89, 207–213 (2022).

Mamkagh, A. The effect of landside length on tractor fuel consumption and depth stability of moldboard Plow. Egypt. J. Agric. Sci. 58, 233–238 (2007).

Dzyuba, O. et al. Studying the influence of structural-mode parameters on energy efficiency of the plough PLN-3-35. Eastern-European J. Enterp. Technol. 3, 55–65 (2019).

Nikolayev, U. A. & Popov, D. V. Energy consumption for overcoming friction of plough landside against the soil. Tractors Agric. Mach. 77, 18–20 (2010).

Vagnik, Y. C., Rajvir, Y. & Gautamray, V. M. Simulation of components of mould board plough bottom using computer software. Int J. Agric Eng. 9, 39–46 (2016).

Girma, G. Dynamic effects of speed, depth and soil strength upon forces on plough components. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 51, 47–66 (1992).

Plouffe, C., McLaughlin, N. B., Tessier, S. & Lague, C. Energy requirements and depth stability of two different moldboard plow bottoms in a heavy clay soil. Can. Agric. Eng. 37, 279–285 (1995).

Saunders, C., Godwin, R. J., Dogherty, M. J. O. & Mk, B. Prediction of soil forces acting on mouldboard ploughs. J. Terramechanics. 44, 3–14 (2007).

Abdallah, F. E., Ding, W., Ding, Q. & Pan, G. Design, development, and performance evaluation of a trash-board moldboard plow for the interaction between soil and straw with two different water content levels. Agronomy 6, 30 (2016).

Cardei, P., Matache, M. & Cristea, O. Optimum working conditions for variable width plougs. INMATEH - Agric. Eng. 65, 248–254 (2021).

Guskov, V. V. et al. Tractors: Theory. (Moscow: Mashinostroenie (in Russian), (1988).

Bulgakov, V. et al. Theoretical background for increasing grip properties of wheeled tractors based on their rational ballasting. Agraart J. Agric. Sci. 30, 78–84 (2019).

Nadykto, V. et al. Determination of operation performance indicators of unit for mowing crops with the simultaneous incorporation of their stubble into the soil. Sci. Rep. 14, 15373. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66183-x (2024).

Nadykto, V. et al. Experimental studies on the operation of agricultural crops mowing unit with simultaneous chopping and incorporation of stubble into the soil. Agricultural Eng. 27 (1), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.2478/agriceng-2023-0022 (2023).

Dospekhov, B. A. Field Experiment Methodology (with the Basics of Statistical Processing of Research Results). (Moscow: Agropromizdat (in Russian), (1985).

Gardner, W. A. Statistical Spectral Analysis-A Nonprobabilistic Theory (Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1988).

Schumacker, R., Tomek, S. & Understanding Statistics Using, R. Springer, New York, NY, (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6227-9_11

Acknowledgements

The anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged for their constructive reviews that significantly improved this manuscript, as well as the International Visegrad Fund (www.visegradfund.org, accessed on 8.08.2025) and the Ukrainian University in Europe (https://universityuue.com/, accessed on 8.08.2025).

Funding

This project has received funding from the Ministry of Education of Science Republic of Poland for the Agricultural University in Krakow for the year 2025 and the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports of the Republic of Lithuania and Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under the Program’ University Excellence Initiative’ Project ‘Development of the Bioeconomy Research Center of Excellence’ (BioTEC), agreement № S-A-UEI-23-14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N, T.H., and G.G.; methodology, V.N, T.H., and V.K.; software, V.N., I.H.; validation, I.H., P.K.; formal analysis, V.P. and V.K; resources, T.H.; data curation, V.N. and G.G.; visualization, V.P.; project administration, V.N.; funding acquisition, P.K.; supervision, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadykto, V., Horetska, I., Kyurchev, V. et al. Design parameters justification of the plough bottom’s landside. Sci Rep 15, 43713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27466-z