Abstract

Delayed-start contraception may reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy; however, data on newer formulations, such as estetrol (E4)-containing pills are limited. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of delayed start combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing 15 mg E4 and 3 mg drospirenone (E4/DRSP). In this randomized, single-blind, non-inferiority trial, 36 healthy women aged 18–45 years with regular menstrual cycles were assigned to receive either E4/DRSP or 20 µg ethinyl estradiol/75 µg gestodene (EE/GS), starting treatment between cycle day 7 and 9. The primary outcome was ovulation inhibition, assessed using the modified Hoogland score. The secondary outcomes included cervical mucus changes and adverse effects. Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the groups. The mean age and menstrual cycle length were 38.75 ± 5.8 years and 28.67 ± 1.96 days, respectively. More than half (55.56%) of the participants began COC use on day 9, with 50% of them showing active follicular development at baseline (Hoogland score of 4). Ovulation was inhibited in 61.11% of participants in both groups (adjusted relative risks: 0.95, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.56–1.59, p = 0.841, and absolute risk difference: −0.03, 95% CI: −0.39 to 0.33). Approximately half of the participants who ovulated showed ovarian activity that was not associated with theoretical pregnancy risk. Cervical mucus profiles and adverse events, including unscheduled bleeding, did not differ significantly between the groups. Initiating E4/DRSP on cycle day 7–9 appears comparable to that of EE/GS for ovulation inhibition; however, high ovulation rates limit the confirmation of non-inferiority.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Registration on April 25, 2024 (ID: NCT06396221; https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06396221).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) are among the most widely used contraceptive methods worldwide1, including in Thailand2. COCs contain two hormonal components, progestin and estrogen, that act synergistically to prevent ovulation. The progestin component primarily exerts its contraceptive effects by inhibiting ovulation through negative feedback on luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion. Progestin also influences cervical mucus, fallopian tube function, and the endometrium, thereby impairing fertilization and implantation. The estrogen component stabilizes the endometrium to minimize unscheduled bleeding and enhances progestin efficacy by upregulating progesterone receptor expression and suppressing follicle development via follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) negative feedback3,4,5,6.

Ethinyl estradiol (EE), a synthetic estrogen, is widely used in COCs because of its strong effects on FSH suppression and endometrial stabilization. EE significantly influences hepatic protein synthesis, potentially contributing to increased blood pressure, enhanced drug interactions, and a higher risk of venous thromboembolic events in susceptible individuals3,4,5. Because of these safety concerns, alternative estrogens have been used as COCs instead of EE. Estetrol (E4) is an estrogen structurally identical to the hormone naturally produced by the fetal liver during pregnancy. It has been developed for clinical use because of its unique pharmacological profile. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 15 mg E4 combined with 3 mg drospirenone (DRSP) (E4/DRSP) for contraceptive use. E4 is considered an estrogen with selective tissue activity (NEST), designed to mimic certain physiological properties of endogenous estrogens. It preferentially activates nuclear estrogen receptors while exerting minimal effects on membrane-bound receptors in the presence of estradiol (E2). E4 may provide several advantages over EE, including a reduced impact on hepatic protein synthesis, potential anti-proliferative effects in breast tissue, and beneficial effects on the vaginal epithelium, endometrium, bone, brain, and vascular system4,5,7,8. Previous pharmacodynamic studies have reported that E4/DRSP inhibits ovulation and exerts beneficial effects on multiple target tissues, with a potentially improved safety profile compared with that of EE-containing pills7,8,9,10.

Quick-start contraception, defined as initiation of contraception immediately regardless of the cycle day, is recommended by several organizations to improve contraceptive access, convenience, and adherence as well as to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy3,11,12. However, clinical evidence remains limited, particularly for COCs containing E4. Moreover, data on the pharmacodynamic effects of E4/DRSP when initiation is delayed to cycle day 7–9 are scarce, despite this representing a common pattern of contraceptive use in clinical practice. To address these gaps, we hypothesized that E4/DRSP would be non-inferior to the widely used 20-µg EE/75-µg gestodene (EE/GS) formulation in inhibiting ovulation when initiated in this delayed manner. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing E4/DRSP with EE/GS, with ovulation inhibition as the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints included changes in cervical mucus quality, assessed using the modified World Health Organization (WHO) score13, as well as adverse events associated with delayed-start COC use.

Materials and methods

Study design

A single (investigator)-blinded, randomized controlled non-inferiority trial was conducted at the Family Planning and Reproductive Health Unit of King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Thailand, from May 1 to September 29, 2024. The protocol was developed in accordance with International Good Clinical Practice regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki; approved by the Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (0839/66); and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on April 25, 2024 (ID: NCT06396221). Before enrollment, all participants provided written informed consent and received 500 baht (approximately $15) per visit as compensation for their time.

Randomization was performed using computer-generated blocks of four to allocate participants into two groups (E4/DRSP or EE/GS) in a 1:1 ratio. Assignments were sealed in uniquely labeled envelopes and opened at visit 2 by a research assistant who was not involved in data collection or analysis. The principal investigator (IS) performed transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and collected cervical mucus samples. Participants were instructed to keep their medication in the original envelope and return it to the same research assistant at each visit for compliance monitoring to maintain the single-blind design.

Participants

Eligible participants were healthy women aged 18–45 years with regular menstrual cycles and a body mass index (BMI) of 18–30 kg/m2 who either agreed to use condoms or were sterilized. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to estrogen or progestin use14, pregnancy, lactation, exogenous hormone use within 3 months, cervical neoplasia, ovarian cysts/tumors, or a pre-existing leading follicle measuring > 10 mm on TVUS screening (cycle day 1–2) (see Supplementary Table S1).

Study protocol

At visit 1 (cycle day 1–2), initial screening included medical history assessment, physical examination, urine pregnancy testing, and TVUS. Enrolled participants registered with the Line Official Account (Line OA) application to facilitate contact.

Visit 2 (day 7–9) included TVUS; cervical mucus collection; and blood sampling to measure estradiol, progesterone (P), and LH levels. Participants received the study medication according to the randomized, labeled envelopes and were provided with a diary to record pill intake and any side effects, including bleeding episodes. All participants were instructed to take the first pill on that day and continue taking one pill daily at approximately the same time throughout the study period.

Follow-up visits were initially conducted every 3–4 days to assess ovarian activity, ovulation inhibition, cervical mucus, and serum hormone levels. This continued until one of the following three conditions occurred: (1) the largest follicular-like structure diameter (LFD) reached ≥ 15 mm, prompting visits every 2–3 days, and the schedule was reduced to every 7 days if the follicle size remained stable without ovulation for three visits; (2) LFD measured < 13 mm on three consecutive visits; and (3) ovulation occurred. For conditions (2) and (3), visits were scheduled every 7 days until the completion of the pill pack. Visit schedules for other secondary outcomes are shown in Fig. 1. If more than 3 days had passed since the previous visit before completing the pill pack, the final visit was scheduled for the day of the last pill.

aE2, P, and LH. Serum E2 and P levels were analyzed using competitive electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA, Cobas, Switzerland), whereas LH levels were analyzed using the sandwich ECLIA method. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were under 4%, and detection limits were 5 pg/mL (18.35 pmol/L), 0.05 ng/mL (0.159 nmol/L), and 0.1 IU/L for estradiol, progesterone, and LH, respectively.

bDay of completion of the pill pack. cP > 1.57 ng/mL ± postovulatory image.

dDay of the menstrual cycle. eVisit 3 onward, hormonal level and TVUS assessment were performed every 3–4 days. The frequency of visits were adjusted based on TVUS findings and hormonal levels.

-

Follicle size ≥ 15 mm: TVUS every 2–3 days until ovulation or for three visits in women without ovulation. Subsequently, TVUS was performed every 7 days until the pill pack was completed.

-

Follicle size < 13 mm for three consecutive visits: Subsequent TVUS was performed every 7 days until the pill pack was completed.

-

Evidence of ovulation: Subsequent TVUS was performed every 7 days until the pill pack was completed.

fThe last visit was scheduled on day 28 of the pill pack if the previous visit occurred >3 days earlier.

gTVUS was performed using a Voluson S10 (SN: US919F1869) with a transvaginal probe (IC9-RS; 2.9–9.7 MHz).

hFrom visit 4 onward, cervical mucus examination was performed if the previous modified WHO score was ≤4 for the first time or >4, and was discontinued when the score was ≤4 for two consecutive visits.

Study medication

The intervention group received E4/DRSP (Nextstellis®; Haupt Pharma Münster GmbH, Germany), consisting of 24 active (15 mg estetrol monohydrate and 3 mg drospirenone) and 4 placebo tablets. The control group received EE/GS (Annylyn® 28; Thai Nakorn Patana, Thailand), consisting of 21 active (20 µg ethinyl estradiol and 75 µg gestodene) and 7 placebo tablets. The EE/GS COC was selected as the comparator because it is widely used in clinical practice and has documented efficacy when initiated using a delayed-start regimen17,27. Daily reminders were sent via the Line OA chat at 8:00 p.m., prompting participants to confirm their medication intake. Missing a dose for more than 24 h was considered a protocol deviation; however, these participants were still included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

Outcomes

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate ovulation inhibition and ovarian activity throughout the completion of the pill pack when initiated in a delayed manner. Secondary outcomes included the time to develop unfavorable cervical mucus after treatment initiation and the occurrence of adverse events.

Ovulation inhibition and ovarian activity

The principal investigator (IS) performed TVUS to assess the outcomes using the modified Hoogland scoring (mH/S) system, which incorporates TVUS findings along with serum estradiol and progesterone levels (see Supplementary Table S2)30. The modified Hoogland score30, rather than the original score10, was used because it provides a more clinically relevant classification of ovarian activity by distinguishing normal from abnormal luteal function, thereby enabling a more accurate assessment of luteal phase adequacy and the associated theoretical risk of pregnancy. Moreover, its use ensures consistency with recent pharmacodynamic studies of delayed-start regimens, enhancing the comparability of findings.

The “follicle-like structure (FLS)” refers to ovarian follicles or cystic structures identified on TVUS. Blood samples were collected in the morning using 5-mL clot-activated tubes and delivered to an ISO 15,189–certified laboratory at the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, within 30 min.

Based on the modified Hoogland score30, ovulation was defined as an mH/S score > 4 (P > 1.57 ng/mL with or without a postovulatory image). Ovulation accompanied by a normal luteal phase, indicated by a serum progesterone level > 9.42 ng/mL or between 3.14 and 9.42 ng/mL on two consecutive measurements, was considered to represent a theoretical risk of pregnancy. Ovarian activity was subclassified based on follicular progression, as indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

Cervical mucus

Within 30 min after cervical mucus collection (see Supplementary Fig. S1), a trained scientist analyzed the mucus using the methods outlined in the WHO Laboratory Manual (5th Edition), as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S213. All findings were photographed, documented, and verified by the principal investigator (IS). Inconclusive cases were reviewed jointly by IS and the same trained scientist. A modified WHO scoring system (maximum score of 12) was used to assess cervical mucus characteristics (Supplementary Table S4). Scores ≤ 4 were considered to indicate unfavorable mucus13,31. Cycles in which ovulation occurred before mucus became unfavorable were excluded from the analysis because of the influence of progesterone on mucus properties.

Adverse events

Participants were instructed to record side effects, including bleeding, in their diaries. These logs were reviewed during follow-up visits. Scheduled bleeding was defined as any bleeding that occurred within 7 days of taking the first hormone-free pill32,33. Unscheduled bleeding was defined as any bleeding or spotting that occurred outside the scheduled bleeding period. Spotting was defined as any vaginal bloody discharge that did not require sanitary protection, whereas bleeding was defined as vaginal bleeding that did require sanitary protection (tampon, pad, or pantyliner)34.

Statistical methods

Sample size calculation

When initiated on cycle day 1, the 15-mg E4/3-mg DRSP regimen has been shown to adequately inhibit ovulation, comparable to a marketed COC containing 20 µg EE/3 mg DRSP10. A delayed-start contraception study showed that a 20-µg EE/75-µg GS COC achieved a 95% ovulation inhibition rate when initiated on cycle day 7–917. In contrast, Sitavarin et al. reported 91% ovulation inhibition with fixed-start days (1 vs. 7)27, which is less directly comparable to our study design. This study aimed to evaluate whether E4/DRSP is as effective as 20 µg EE/75 µg GS in inhibiting ovulation. A non-inferiority trial design, with 80% statistical power, a one-sided alpha of 5%, and a non-inferiority margin of 20%, was used. To account for a potential dropout rate of 20%, the final calculated sample size was 18 participants per group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp, 2017; College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were applied where appropriate. A generalized linear model with a binomial distribution and log link was used to estimate the risk ratios (RRs) with confidence intervals (CIs) for ovulation inhibition between the treatment groups. Multivariable models were adjusted for potential confounders, including cycle length, pill initiation day, and follicular size at initiation. The absolute risk difference (ARD) was also calculated to determine whether the outcomes fell within the predefined 20% non-inferiority margin. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test were used to assess the cumulative ovulation incidence. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Both per-protocol (PP) and ITT analyses were performed on all randomized participants; however, only ITT results were reported when both approaches produced comparable findings. In the ITT analysis, missing data were imputed using the last baseline observation carried forward method for most endpoints, including ovulation. For continuous variables, imputation was performed using group mean values.

Results

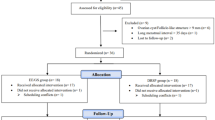

Of the 46 women screened, 36 were enrolled and randomly allocated to either the study group (E4/DRSP, n = 18) or the control group (EE/GS, n = 18) (Fig. 2). One participant from the EE/GS group was lost to follow-up after visit 2. No protocol deviations occurred. Consequently, the PP analysis included 17 participants in the EE/GS group and 18 in the E4/DRSP group, and all 36 participants were included in the ITT analysis.

The demographic profiles of the participants were similar between the two groups, except for the prevalence of overweight and obesity based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria15, which differed significantly (E4/DRSP vs. EE/GS: underweight to normal weight, 50% vs. 77.78%; overweight to obesity, 50% vs. 22.22%, p = 0.028) (Table 1). However, when the WHO criteria for Asian populations were used16, the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, after subclassifying the average menstrual interval and the LFD at the first visit, no significant differences were observed between the groups.

At the time of medication initiation, the day of the cycle, the modified Hoogland scores, ovarian status, and the modified WHO scores for cervical mucus did not differ significantly across the groups (Table 2). Most participants in both arms began taking the pill on day 9 of the cycle. However, the menstrual cycle length of participants from both arms, classified by the day of pill initiation, did not differ significantly between the two groups. Based on the modified Hoogland scores, ovulation inhibition occurred in 11 participants in each group (61.11%) (RR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.59–1.68, p = 1.000; Table 3). The multivariable analysis adjusted for cycle length, day of starting pill (day 7–9), and follicular size at starting pill showed a lower RR of ovulation inhibition in the E4/DRSP group than in the EE/GD group, although the difference was not statistically significant (adjusted RR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.56–1.59, p = 0.841, and ARD = − 0.03, 95% CI: −0.39 to 0.33; Fig. 3). Among the factors analyzed for association with ovulation, only the LFD at pill initiation was significant. An LFD > 12.4 mm was associated with a significantly lower rate of ovulation inhibition than an LFD ≤ 12.4 mm (adjusted RR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.38–1.00, p = 0.049). All participants who ovulated had an LFD > 12.4 mm at the start of treatment. Shorter menstrual cycle length (24–28 days vs. 29–33 days) and later pill initiation (day 9 vs. day 7–8) tended to decrease the rate of ovulation inhibition; however, the difference was not statistically significant. The Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrated an ovulation rate of 2.13 per 100 person-days (95% CI: 1.01–4.46, p = 0.957; Supplementary Fig. S3A) and an ovulation inhibition rate of 3.34 per 100 person-days (95% CI: 1.85–6.04, p = 0.261; Supplementary Fig. S3B), with no significant difference between the groups.

Absolute risk difference (ARD) for ovulation inhibition. Error bars indicate two-sided 95% CIs. The dashed blue line at x = Δ represents the 20% non-inferiority margin. The region shaded in blue to the left of x = Δ represents the zone of non-inferiority. An ARD of − 0.03 (− 0.39 to 0.33) indicates that the predefined non-inferiority margin could not be statistically confirmed. EE/GS, 20 µg ethinyl estradiol plus 75 µg gestodene; E4/DRSP, 15 mg estetrol plus 3 mg drospirenone.

Comparisons of ovarian activity between the study groups (Table 4) revealed no significant differences in the maximal modified Hoogland scores or ovarian status during or at the end of the study. Although ovulation occurred in seven participants per study arm, only four per arm were considered at theoretical risk of pregnancy based on adequate progesterone levels during the luteal phase. The remaining three in the study arm who had inadequate progesterone levels or duration (mH/S of 5 or 6 on a single occasion) were categorized as having ovarian activity with no theoretical risk of pregnancy. At the end of the study, most participants were classified as having ovarian quiescence (83.33% in each group), whereas the remaining 16.67% were classified as having ovarian activity but not at a theoretical risk of pregnancy. No significant differences in ovarian activity progression were observed between the groups throughout the study. Although the E4/DRSP group showed a trend toward a shorter duration from pill initiation to ovulation than the EE/GS group (4.71 ± 1.60 days vs. 6.86 ± 2.27 days), the difference was not significant (p = 0.076).

In the E4/DRSP group, 11 participants (61.11%) achieved a modified WHO cervical mucus score of ≤ 4 for two consecutive visits before or without ovulation, indicating that cervical mucus could be rendered unfavorable for fertility, compared with 8 participants (44.44%) in the EE/GS group; however, the difference between the two groups was not significant (p = 0.505; Table 5). The mean interval required to achieve two consecutive visits with unfavorable cervical mucus from the starting day was 8.36 ± 7.24 days in the E4/DRSP group and 5.75 ± 2.92 days in the EE/GS group (p = 0.277). The median interval was 4 days (IQR 3–14) for E4/DRSP and 4 days (IQR 4–8) for EE/GS. More than half of the participants experienced changes in the cervical mucus within 7 days. Only one participant in the E4/DRSP group exhibited unfavorable cervical mucus before ovulation. When participants who ovulated before cervical mucus changes were excluded, LFD and estradiol levels at pill initiation were analyzed for their potential influence on cervical mucus changes. Both estradiol levels and LFD were lower in the group in which the treatment inhibited cervical mucus than in the group where it did not; however, the differences in the two parameters were not significant. Supplementary Fig. S4 shows trends in LFD and hormone levels over the study period. Supplementary Fig. S5 shows the LFD, hormone levels, and day of ovulation for the participant whose cervical mucus remained persistently suppressed for two consecutive visits (visits 2–3) before ovulation (visit 4).

Scheduled bleeding occurred in a similar proportion of participants in both groups, with 16 participants (88.89%) in each group (p = 0.439) (Table 5). No significant difference was observed in the rate of unscheduled bleeding between the groups: seven participants (38.89%) in the E4/DRSP group versus four participants (23.53%) in the EE/GS group (p = 0.471). Among the seven participants in the E4/DRSP group, five experienced bleeding and two experienced spotting. In the EE/GS group, three participants experienced only bleeding, whereas one participant experienced bleeding and spotting. These episodes occurred despite good compliance. Unscheduled bleeding/spotting tended to occur near the end of the active pill phase in the E4/DRSP group, whereas bleeding/spotting occurred in a more random pattern throughout the cycle in the EE/GS group. The rates of other adverse events did not differ significantly between the groups (Table 5).

Discussion

Primary findings

This randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of a COC containing 15 mg of estetrol and 3 mg of drospirenone compared with a standard COC containing 20 µg of EE and 75 µg of gestodene for ovulation inhibition using a delayed-start regimen (cycle day 7–9). Both groups demonstrated comparable ovulation inhibition rates (61.11%). The predefined non-inferiority margin could not be statistically confirmed; thus, the non-inferiority of the E4/DRSP formulation could not be concluded.

The ovulation inhibition rate in the EE/GS group was lower than that reported in previous delayed-start studies, which demonstrated ovulation inhibition rates ranging from 78% to 95%17,18. This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors. First, participants in our study were older (mean age: 38.67 ± 6.12 years vs. 32.5 ± 6.12 years) and had shorter menstrual cycles (28.44 ± 2.31 days vs. 31.9 ± 3.5 days) than those in the earlier study17. Advancing age is associated with shortened cycle intervals and earlier follicular development, potentially resulting in more advanced ovarian activity at the time of pill initiation19,20. Second, in our study, pill initiation occurred later in the follicular phase, with most participants starting on day 9 of the cycle, whereas prior studies typically initiated treatment earlier, on the seventh or eighth day of the cycle17,18. This delay may have allowed further follicular maturation to a point where hormonal contraception could no longer effectively inhibit ovulation21,22. Almost 50% of the participants in our study had a modified Hoogland score of 4 at pill initiation, indicating active ovarian activity, whereas most participants in previous studies had scores below 3, reflecting inactive or only potentially active follicles17,18. Furthermore, among participants who ovulated in our study, we observed significantly larger follicular diameters at the time of pill initiation than among those who did not ovulate, supporting the hypothesis that more advanced follicular development at baseline contributed to the higher observed ovulation rate. Overall, these differences in participant characteristics, pill initiation timing, and baseline ovarian activity likely contributed to the unexpectedly high ovulation rates in both arms of our study. Consequently, despite the clinically equivalent ovulation outcomes between the two groups, the ability to statistically confirm non-inferiority may have been limited.

No significant differences in ovarian activity were observed throughout the study period or at the end of the study. The time to ovulation tended to be shorter in the E4/DRSP group, possibly because of comparatively lower gonadotropin suppression by E4 versus EE. Duijkers et al.10 demonstrated in a phase II trial that although 15 mg of E4 combined with 3 mg of DRSP effectively inhibited ovulation, it was associated with reduced follicular suppression and a more rapid return of ovulatory function upon discontinuation, indicating partial suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis relative to EE-based formulations.

Among the 14 participants who ovulated, the longest interval to ovulation was observed in the EE/GS group at 10 days. These findings suggest that the current 7-day backup contraception recommendation may be insufficient11. Although based on limited evidence, our study suggests that extending backup contraception to more than 10 days may be more appropriate when initiating COCs using the quick-start approach.

Approximately half of the participants in both groups achieved a modified WHO cervical mucus score of ≤ 4 for two consecutive visits. Unfavorable cervical mucus was observed more frequently in the E4/DRSP group than in the EE/GS group, likely due to differences in progestin and estrogen pharmacodynamics. DRSP has a longer half-life and stable progestogenic activity, promoting consistent mucus thickening, whereas the shorter half-life of gestodene may lead to hormonal fluctuations23. Additionally, E4 has weaker estrogenic stimulation of the cervical glands than EE, allowing progestin effects to dominate and maintain unfavorable cervical mucus24. However, this result may underestimate the true effect, as participants who ovulated were exempted from cervical mucus testing. More than half of those who did not ovulate and underwent mucus assessment developed a persistent change to unfavorable cervical mucus within 7 days of initiating the study medication. The maximum duration required to achieve this change was 23 and 11 days in the E4/DRSP and EE/GS groups, respectively, substantially exceeding the current 7-day backup contraception recommendation for quick-start initiation if cervical mucus is used as the basis for pregnancy prevention. Nonetheless, these estimates may not accurately reflect the true timing of mucus transformation because most follow-up visits occurred at 7-day intervals, limiting the precision of assessment.

Scheduled bleeding occurred in nearly all participants, with a duration of approximately 3–4 days, and the rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the E4/DRSP group, unscheduled bleeding or spotting commonly occurred toward the end of the active pill phase, particularly between cycle day 21 and 24, a pattern called early scheduled bleeding. This may be attributed to the NEST properties of E4. Compared with EE, E4 has weaker estrogenic activity on the endometrium, resulting in less endometrial proliferation and stabilization. Consequently, the endometrial lining becomes more prone to early shedding. This pattern has been observed in clinical studies involving E4/DRSP users25,26. The use of a delayed-start regimen in our study may have further contributed to this bleeding pattern. Other adverse events were mild and did not result in discontinuation from the study.

We selected the 20-µg EE/75-µg GS formulation (Annylyn® 28) as the control medication for ovulation inhibition in the delayed-start regimen because it is a commonly used contraceptive, and previous studies have demonstrated its efficacy in inhibiting ovulation when initiated in a delayed-start manner17,27. In previous studies, various COC types were evaluated using delayed-start protocols; however, most of them compared the same formulation under different conditions, such as follicle size (30 µg EE/150 µg desogestrel)21 or cycle day at initiation (30 µg EE/300 µg norgestrel, 20 µg EE/75 µg GS, 30 µg EE/150 µg LNG)22,28. EE/GS was the only commonly used COC regimen studied in delayed-start protocols that initiated pills beyond the recommended window (day 1–5), making it the most appropriate comparator for our study17.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several notable strengths. First, the E4-containing COC has been approved for contraceptive use since 2021; however, data on its effectiveness when initiated using a delayed-start protocol are limited. This study may provide foundational knowledge regarding this new COC, which is recognized for its favorable safety profile29. Second, COCs primarily prevent pregnancy by inhibiting ovulation, with cervical mucus changes serving as a secondary mechanism. In this study, we assessed cervical mucus changes to evaluate this additional mechanism of fertility suppression in the context of a delayed-start regimen. Third, the effectiveness of COCs for each outcome was evaluated using established standard methods—for example, ovulation and ovarian activity inhibition were assessed using the modified Hoogland score, a derivative of the original Hoogland and Skouby score, whereas cervical mucus permeability was evaluated using the WHO Laboratory Manual (5th Edition) criteria. Fourth, to minimize potential bias and adjust for known and unknown confounders, we conducted a randomized controlled trial with investigators blinded to both ovarian activity and cervical mucus outcomes. Fifth, outcome assessments were assigned to a single trained investigator per parameter to reduce interobserver variability. Finally, participant adherence was closely monitored through daily check-in messages to confirm medication intake, minimizing the risk of protocol deviations and loss to follow-up.

Several limitations may affect the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. Variability was observed in the timing of COC initiation, which ranged from day 7 to 9 of the menstrual cycles of our participants. This inconsistency may have led to overestimation or underestimation of outcomes, particularly in participants with shorter or longer cycles. Although daily monitoring is ideal for determining ovulation accurately, our protocol did not include daily assessments. Instead, ovulation detection relied on serial TVUS and serum progesterone measurements, all performed by a single operator to maintain consistency, an approach that enabled reliable identification of ovulatory events despite lower granularity. Adherence was monitored through pill counts and participant diaries; however, neither the precise timing of pill intake nor the accuracy of diary entries could be confirmed. In addition, no pharmacokinetic data were collected, which may have provided important insights for interpreting the pharmacodynamic findings and elucidating inter-individual variability. Finally, although the fixed-cycle design mirrors real-world clinical practice, certain questions remain unanswered, particularly concerning women with shorter menstrual cycles or those initiating COCs during the late follicular phase. Therefore, further research is required to optimize contraceptive strategies and guidance in such populations.

Conclusion

Initiating estetrol/drospirenone therapy between day 7 and 9 of the menstrual cycle may offer comparable ovulation inhibition to ethinyl estradiol/gestodene. However, the unexpectedly high ovulation rates observed in both groups and the lack of statistical significance preclude a definitive conclusion regarding non-inferiority. The time to achieve unfavorable cervical mucus changes exceeded the currently recommended 7-day backup contraception period, indicating that a delayed-start regimen may require a longer duration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Somsook Santibenchakul, upon reasonable request. All requests will be reviewed to ensure compliance with ethical and confidentiality guidelines before data sharing.

Change history

16 January 2026

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding section in the original version of this Article contained errors. The original version of the Funding section read: This research was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Graduate Affairs, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. Their Financial support was instrumental in conducting the experiments, analyzing the data, and facilitating the dissemination of the fundings”. The Funding section now reads: “This study was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, via the Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Clinical Research Center Under the Royal Patronage and Chula Data Management Center [Grant number RA67_CRC_002]. Their financial support was instrumental in conducting the experiments, analyzing the data, and facilitating the dissemination of the findings.”

References

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Contraceptive use by method 2019: Data booklet [Internet]. (2019). https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210046527 (United Nations.

National Statistical Office of Thailand. Thailand multiple indicator cluster survey 2022. Survey Findings Report 2023 [Internet]. (2023). https://www.unicef.org/thailand/media/11361/file/Thailand%20MICS%202022%20full%20report%20(Thai).pdf

Curtis, K. M. et al. U.S. Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 65, 1–66 (2016).

Lee, A. & Syed, Y. Y. Estetrol/drospirenone: a review in oral contraception. Drugs 82, 1117–1125 (2022).

Voedisch, A. J. & Fok, W. K. Oestrogen component of cocs: have we finally found a replacement for Ethinyl estradiol? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 33, 433–439 (2021).

Christin-Maitre, S. History of oral contraceptive drugs and their use worldwide. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 3–12 (2013).

Morimont, L., Haguet, H., Dogné, J. M., Gaspard, U. & Douxfils, J. Combined oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: review and perspective to mitigate the risk. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 655490 (2021).

Gallez, A., Dias Da Silva, I., Wuidar, V., Foidart, J. M. & Péqueux, C. Estetrol and mammary gland: friends or foes? J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 26, 297–308 (2021).

Duijkers, I. J. et al. Inhibition of ovulation by administration of estetrol in combination with Drospirenone or levonorgestrel: results of a phase II dose-finding pilot study. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care. 20, 476–489 (2015).

Duijkers, I. et al. Effects of an oral contraceptive containing estetrol and Drospirenone on ovarian function. Contraception 103, 386–393 (2021).

Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. FSRH Clinical Guideline: Quick Starting Contraception (FSRH, 2017).

Chen, M. J., Kim, C. R. & Whitehouse, K. C. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am. Fam Physician. 103, 291–299 (2021).

World Health Organization. WHOlaboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen 5th edn (World Health Organization, 2010).

Curtis, K. M. et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 65, 1–103 (2016).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy weight: assessing your weight: adult BMI [Internet]. [cited 2025 February 6]. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 363, 157–163 (2004).

Jirakittidul, P. et al. The effectiveness of quick starting oral contraception containing nomegestrol acetate and 17-beta estradiol on ovulation inhibition: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 10, 8782 (2020).

Ratanasaengsuang, A. et al. A randomized single-blind non-inferiority trial of delayed start with drospirenone-only and Ethinyl estradiol-gestodene pills for ovulation Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 14, 14151 (2024).

Fleming, R. & Telfer, E. E. The dynamics of follicular development in the aging human ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update. 14, 503–514 (2008).

Klein, N. A., Harper, A. J., Houmard, B. S., Sluss, P. M. & Soules, M. R. Is the short follicular phase in older women secondary to advanced or accelerated dominant follicle development? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 5746–5750 (2002).

Baerwald, A. R., Olatunbosun, O. A. & Pierson, R. A. Effects of oral contraceptives administered at defined stages of ovarian follicular development. Fertil. Steril. 86, 27–35 (2006).

Taylor, D. R., Anthony, F. W. & Dennis, K. J. Suppression of ovarian function by microgynon 30 in day 1 and day 5 starters. Contraception 33, 463–471 (1986).

Palacios, S. et al. Drospirenone 4 mg in a 24/4 regimen maintains Inhibition of ovulation even after a 24-h delayed pill intake—pharmacological aspects and comparison to other progestin-only pills. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 1994–1999 (2022).

Foidart, J. M. et al. Estetrol, a fetal selective Estrogen receptor modulator, acts on the vagina of mice through nuclear Estrogen receptor α activation. Am. J. Pathol. 187, 2531–2540 (2017).

Apter, D. et al. Bleeding pattern and cycle control with estetrol-containing combined oral contraceptives: results from a phase II, randomised, dose-finding study (FIESTA). Contraception 94, 366–373 (2016).

Kaunitz, A. M. et al. Pooled analysis of two phase 3 trials evaluating the effects of a novel combined oral contraceptive containing estetrol/drospirenone on bleeding patterns in healthy women. Contraception 116, 29–36 (2020).

Sitavarin, S., Jaisamrarn, U. & Taneepanichskul, S. A randomized trial on the impact of starting day on ovarian follicular activity in very low dose oral contraceptive pills users. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 86, 442–448 (2003).

Schwartz, J. L., Creinin, M. D., Pymar, H. C. & Reid, L. Predicting risk of ovulation in new start oral contraceptive users. Obstet. Gynecol. 99, 177–182 (2002).

Mommers, E. H. P. et al. Safety and tolerability of estetrol/drospirenone 15 mg/3 mg combined oral contraceptive: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Contraception 110, 14–21 (2020).

Banh, C. et al. The effects on ovarian activity of delaying versus immediately restarting combined oral contraception after missing three pills and taking ulipristal acetate 30 mg. Contraception 102, 145–151 (2020).

Lopez, L. M., Newmann, S. J., Grimes, D. A. & Nanda, K. Schulz K.F. Immediate start of hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, Cd006260 (2019).

Pretorius, R. G., Ginsburg, E. S., Thomas, M. A. & Archer, D. F. Contraceptive efficacy, bleeding patterns, and safety of a 91-day extended-regimen oral contraceptive with continuous low-dose Ethinyl estradiol. Contraception 104, 222–228 (2021).

Archer, D. F., Johnson, J. V., Borisute, H., Cohen, R. & Mirkin, S. Effects of extended regimen combined oral contraceptives with and without a 1-week break on ovarian activity: results from a randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Sci. 21, 1518–1525 (2014).

Mishell, D. R. et al. Recommendations for standardization of data collection and analysis of bleeding in combined hormone contraceptive trials. Contraception 75, 11–15 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Family and Reproductive Health Research Unit team, particularly Ms. Nantana Thongrod, for her valuable contributions. Finally, we extend our appreciation to the Reproductive Medicine Division and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for granting permission to conduct this research and for their continued institutional support.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, via the Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Clinical Research Center Under the Royal Patronage and Chula Data Management Center [Grant number RA67_CRC_002]. Their financial support was instrumental in conducting the experiments, analyzing the data, and facilitating the dissemination of the findings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IS conducted the literature review, developed the study concept and experimental design, acquired data, performed ultrasound assessments of follicle activity, interpreted data, and drafted the primary manuscript. PP managed the data collection platform, interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and edited the manuscript. US contributed to the study concept and experimental design, acquired data, and provided supervision throughout the research. PG supported participant compliance, maintained communication, and facilitated data collection. WR acquired data and interpreted cervical mucus data. UP contributed to data acquisition. SS contributed to the study concept and experimental design, acquired and interpreted data, supervised the research throughout, and revised the manuscript for academic merit. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ittipuripat, S., Phutrakool, P., Uaamnuichai, S. et al. Delayed start of estetrol drospirenone versus ethinyl estradiol gestodene for ovulation inhibition in a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 43682 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27467-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27467-y