Abstract

Hospital-at-home (HaH) care is considered an alternative to inpatient hospitalization. This model of care can serve as an innovative approach aimed at enhancing service delivery while reducing the costs associated with hospital readmissions. The objective of this study was to explore the challenges and advantages of hospital-at-home care from the perspectives of specialists, care providers, and recipients in Iran. This qualitative study was conducted in 2024 using semi-structured interviews. The research population included specialists involved in the implementation of hospital-at-home care programs, as well as providers and recipients of these services in Iran. A total of 27 participants were selected through purposive and snowball sampling. Data analysis was performed using a latent content analysis approach. The software MAXQDA10 was utilized to extract main and subcategories. The content analysis of interviews led to the identification of 50 open codes in total. Among them, 20 codes were categorized under four main themes related to the benefits of hospital-at-home care, including improvement in care delivery, societal and cultural benefits, availability of necessary infrastructure, and cost savings. Meanwhile, 30 codes were classified under seven main themes related to the challenges of hospital-at-home care, including decision-making and policy challenges, time and space limitations (spatial and temporal limitations), legal and ethical challenges, societal and cultural barriers, service delivery constraints, human resource-related challenges, and economic difficulties. The findings of this study highlight both the advantages and challenges of hospital-at-home care in Iran. Given these results, planning by healthcare system managers and policymakers to assess and address the obstacles facing this model of care is crucial. In this regard, several concrete recommendations can be made to enhance the effectiveness of hospital-at-home services. These include adjusting service tariffs to realistic levels, allocating a designated government budget, expanding legally authorized HaH centers, training and developing a skilled workforce, and providing incentive mechanisms such as financial incentives for service providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to population aging, long waiting lists, rising healthcare costs, and limited budgets, both developed and developing countries are actively exploring innovative approaches to improve care delivery and reduce hospital readmissions1. One such approach is home healthcare, which has emerged as an expanding sector within health systems, aiming to replace expensive and specialized hospital care with cost-effective home-based care2. Globally, “Hospital at Home”, a specific form of home healthcare where hospital-level care and treatment are provided at the patient’s residence, has been recognized as a safe and effective alternative to inpatient admission3.

Hospital-at-Home Care is a healthcare delivery model that provides acute, hospital-level medical care to patients in their own homes, under the supervision of medical professionals, as a substitute for traditional inpatient hospitalization4. This model aims to deliver comparable clinical outcomes while enhancing patient comfort and reducing costs5. During the home care process following hospital discharge, a patient who has been hospitalized is released once the acute phase of their illness has passed and they have reached a relatively stable condition, as determined by the treating physician. The patient must consent to the transition to home-based care6.

Hospital-at-home care possesses distinct characteristics that set it apart from other healthcare services7. Unlike traditional care, which requires patients to visit a facility, home hospital care brings providers to the patient’s residence, limiting the provider’s control over the care environment8. Several factors contribute to the expansion of such services. First, the increasing elderly population, along with a growing number of chronically ill and disabled individuals living in the community, necessitate alternative care models9,10.

Second, limited access to alternative healthcare services due to geographic dispersion and regional disparities accelerates the adoption of home care models11,12. Patient and family preferences, as well as the willingness of insurers and providers to support home-based care, further drive this trend11,12.

Despite the growing success of hospital-at-home care in countries like Singapore and New Zealand3,13, the implementation of this specific model in Iran remains underexplored. While Iran’s healthcare system has introduced regulations for post-discharge home hospital care, it is still a relatively new and evolving service. Few studies have examined the unique challenges and advantages of this model in the Iranian context, where specific cultural, economic, and social factors must be considered. This research seeks to fill this gap by exploring both the challenges and benefits of hospital-at-home care in Iran.

In Iran, home hospital care is often limited to individual medical procedures, such as wound dressing changes and intravenous therapy, rather than a comprehensive assessment and management of the patient’s overall care needs14. Unlike more developed systems, such as those in Singapore, where care coordinators identify patients suitable for home care and help manage the transition from hospital to home13, Iranian healthcare providers are still developing the infrastructure and systems needed to implement such models effectively.

Studies indicate that patients generally prefer receiving care at home as it is associated with better recovery, independence, and personal control15. Furthermore, a growing body of research suggests that hospital-at-home models can be highly cost-effective8,9. Despite this, Iranian healthcare policymakers and providers still face significant challenges in adopting these models due to socio-economic and cultural barriers6,14. Therefore, this study was conducted to explore the challenges and benefits of hospital-at-home care services in Iran. The findings of this study can provide evidence-based insights into the advantages and obstacles of home hospital care, contributing to the expansion of knowledge and awareness in this domain. Additionally, the results can assist healthcare system managers and policymakers in planning necessary measures to enhance the effectiveness of such services, ultimately leading to improved healthcare delivery.

Methods

Study design

This study was a qualitative study conducted in 2024 using a latent content analysis approach as both the research design and data analysis method, to gain an in-depth understanding of the challenges and benefits of hospital-at-home care from the perspective of the study participants. Since qualitative research is a systematic method designed to describe experiences and interpret meanings within social organizations, this study also employed a qualitative approach. The purpose of using a qualitative method in this study was exploratory, aiming to investigate a relatively new and under-researched area of care delivery. The study was conducted in Tehran, Iran, where all interviews and data collection took place.

The present study was guided by the principles of latent content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman, which provided a structured approach to interpret the underlying meanings within participant narratives16.

Importantly, the study used a semi-structured interview format with open-ended questions, allowing participants to express their views and elaborate on their experiences freely. This format enabled the researchers to probe deeper into responses using follow-up exploratory questions such as “how,” “why,” and “in what way,” thereby facilitating depth and richness in the data.

Participant selection

The study population consisted of three distinct groups:1 healthcare center managers working within Iran’s healthcare system,2 providers of home care services (nurses, physicians, and support personnel), and3 recipients of hospital-at-home care. Given that qualitative research does not emphasize statistical estimation or large-scale sampling but rather prioritizes the richness and relevance of the sample in relation to the research objective, a purposive snowball sampling method was employed. The study utilized the key informant strategy, meaning that participants were selected based on their relevance to the research rather than through random sampling techniques. To achieve this, the researcher engaged with healthcare center managers, home care providers, and recipients of hospital-at-home services. In addition to conducting interviews with them, the researcher identified individuals with the most extensive knowledge of hospital-at-home care and proceeded to interview them accordingly.

Inclusion criteria were defined separately for each group as follows:

Healthcare managers: at least 5 years of relevant managerial experience in hospital, treatment, or insurance settings; direct involvement in the planning, implementation, or oversight of home care services.

Service providers: at least 3 years of experience delivering hospital-at-home care services; current employment in a relevant healthcare organization.

Service recipients: currently receiving or having received hospital-at-home care for at least one month; aged 18 years or older; cognitively and physically capable of participating in an interview.

Exclusion criteria included: lack of consent to participate, inability to complete the interview due to time constraints or communication difficulties, and absence of any relevant experience with hospital-at-home care.

The final sample size consisted of 27 participants (9 managers, 10 service providers, and 8 recipients. The saturation point was reached after 27 interviews, as no new themes emerged from the data, ensuring that the sample size was appropriate for addressing the research objectives.

Development and pilot of the interview guide

The interview guide was developed based on the existing literature on hospital-at-home care and the research questions. It was designed as a semi-structured guide incorporating open-ended questions to ensure flexibility and allow for the emergence of unanticipated themes. The initial version of the guide was piloted with a small group of participants (n = 4) who were not part of the final study sample. Feedback from the pilot interviews was used to refine and adjust the questions for clarity and relevance to the main study population. The pilot phase also allowed the research team to evaluate and improve their interviewing technique to ensure depth, neutrality, and responsiveness during data collection.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted through open-ended, in-depth (semi-structured) interviews carried out by one of the researchers (PN), who had prior experience and training in conducting qualitative interviews. The interview format consisted of three main sections. The first section introduced the research and explained the purpose of the interviews. The second section gathered demographic and background information about the interviewees. The third section comprised key questions focused on participants’ familiarity with hospital-at-home care processes, as well as the challenges and benefits associated with it.

The number of primary questions in the third section varied depending on the participant group:

Healthcare managers and policymakers were asked 10 questions.

Service providers were asked 7 questions.

Service recipients were asked 8 questions.

Contrary to a fully structured format, the interviews employed open-ended prompts designed to encourage participants to reflect on and describe their experiences in their own words. Follow-up questions and probing techniques were used flexibly and adaptively based on each participant’s responses.

The location and timing of the interviews were determined by the participants, ensuring flexibility on the part of the researcher. Each interview lasted an average of 30 min.

The data collection process was based on an inductive approach, allowing categories and themes to emerge from participants’ narratives rather than being predefined. This approach enabled the researchers to gain deep insights grounded in the actual experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data analysis

Latent content analysis was employed to analyze the data14. The analytical process began with multiple rounds of listening to each interview and thoroughly reading the transcribed text. Open coding was used to identify key phrases and segments of meaning within the content. This was followed by axial coding to group related codes into subcategories and categories. Subsequently, based on continuous comparisons of similarities and differences among the open codes, they were categorized into similar clusters. Codes sharing commonalities were grouped into the same category, forming subcategories. Finally, by merging related categories, the core themes were extracted.

MAXQDA10 software was utilized to manage and organize the data. The software played a crucial role in the coding process and in identifying and visualizing the emerging themes. It was used to facilitate the categorization of codes and the organization of themes, ensuring a systematic approach to data analysis.

Although the study participants included both service providers/recipients (with lived experiences) and subject matter experts (with technical perspectives), the data analysis approach remained within the framework of latent content analysis. This method focuses on interpreting underlying meanings across all participant narratives—whether experiential or expert-based—rather than adopting a phenomenological approach that centers exclusively on individual lived experiences. As such, the methodological stance prioritized thematic abstraction over phenomenological description.

Trustworthiness

The study employed several strategies to ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, following the widely recognized criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba for evaluating qualitative research: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability17,18.

Credibility

The researcher maintained effective communication with participants and shared transcriptions of interviews for member checking, allowing participants to confirm the accuracy of the data. Additionally, peer debriefing was conducted, wherein colleagues reviewed the data and findings for validation. Prolonged engagement with participants and data, as well as triangulation of perspectives from different participant groups (managers, providers, recipients), further enhanced credibility.

Transferability

To enhance transferability, the study provided a clear explanation of its objectives, methodology, and findings. Thick descriptions of the research context, sampling strategy, and participant characteristics were included to enable readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other settings.

Dependability

To enhance dependability, the research process was thoroughly documented, and an audit trail was maintained, including field notes, coding records, and methodological decisions. This allowed for transparency and consistency throughout the study.

Confirmability

The researcher aimed to minimize personal biases during the data collection and analysis process. Reflexivity was practiced by regularly reflecting on how personal assumptions might influence the interpretation of data. Documentation and storage of all materials ensured that findings could be traced back to their sources.

These measures collectively ensured a rigorous qualitative process aligned with the trustworthiness criteria outlined by Lincoln and Guba.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences under the reference number IR.IUMS.REC.1401.583. Ethical considerations were strictly followed by providing a clear and detailed explanation of the study’s objectives and obtaining written informed consent from participants. Furthermore, confidentiality was emphasized, and compliance with the Helsinki Declaration was ensured for the ethical participation of interviewees in the study.

Results

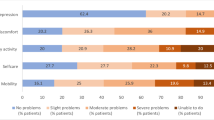

A total of 27 participants took part in the study, including 9 healthcare center managers, 10 home care service providers, and 8 recipients of hospital-at-home care. The average work experience of the interviewed managers and service providers was 19.60 years and 18.28 years, respectively. Participants’ ages ranged from 30 to 65 years, with diverse educational backgrounds including high school diploma (recipients of hospital-at-home care), bachelor’s, and master’s degrees. Job titles varied from nursing and hospital internal manager to head of insurance organization, providing a broad perspective on home-based hospital care. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study participants (Table 1).

The findings led to the identification of 50 open codes, including 20 codes related to the benefits and 30 codes related to the challenges of hospital-at-home care (Fig. 1).

Rather than merely listing participant quotes, the analysis highlighted patterns and connections among statements. For example, phrases such as “reducing waiting time” and “proper follow-up on treatment” were merged into a broader category reflecting systemic improvements in care delivery, illustrating how participants perceived hospital-at-home care as a mechanism to streamline patient management and continuity of care. Similarly, codes related to “patient and family support” and “reduced patient and family anxiety and stress” were combined under “societal and cultural benefits,” showing that home-based care not only addresses medical needs but also strengthens the psychosocial environment for patients and families. This iterative process of comparing, contrasting, and grouping codes led to the development of four main themes for benefits: improvement in care delivery, societal and cultural benefits, availability of necessary infrastructure, and cost savings (Table 2).

In parallel, seven main themes emerged regarding challenges. Open codes such as “lack of insurance coverage,” “legal and ethical concerns,” and “staff resistance” were grouped into categories that reflect broader systemic, organizational, and societal obstacles, including decision-making and policy challenges, time and space limitations, legal and ethical challenges, societal and cultural challenges, service delivery constraints, human resource-related difficulties, and economic difficulties. These thematic groupings provide a deeper understanding of the barriers by linking individual experiences to structural and policy-level factors rather than presenting quotes in isolation (Table 3).

In Tables 2 and 3, selected excerpts from the interviews are presented to illustrate key themes. To maintain confidentiality while providing clarity regarding the source of each perspective, participants are identified using codes. Specifically, participants with codes 12, 13, 17, and 18 represent service recipients; those with codes 4, 7, 9, 11, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 27 represent service providers (such as nurses, physicians, and care staff); and participants with codes 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 14, 19, and 26 represent managers or policymakers. This categorization allows readers to clearly distinguish between the views of different stakeholder groups. This coding enables readers to differentiate perspectives across stakeholder groups while ensuring confidentiality.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that, according to the interviewees, hospital-at-home care is considered an important part of the healthcare system, with both advantages and challenges. Beyond identifying categories, participants’ narratives reflected the deeper meanings they associate with care at home, such as autonomy, dignity, and relational connectedness between patients, families, and providers. The analysis of data from interviews conducted with specialists in the field of hospital-at-home care resulted in the identification of four main categories related to its benefits, which include “improvements in care delivery, community and cultural benefits, availability of required infrastructure, and cost savings,” with 20 subcategories. Additionally, seven main categories related to challenges were identified, including “decision-making and policy challenges, time and space limitations, legal and ethical challenges, community and cultural challenges, service delivery constraints, human resource challenges, and economic difficulties,” with 30 subcategories. While the descriptive presentation of benefits and challenges provides a broad overview, this discussion aims to critically reflect on these findings in the context of existing literature and explore contrasting perspectives.

Importantly, the perspectives of three distinct participant groups-policymakers, service providers, and recipients-are considered separately to provide a more nuanced understanding of the findings and inform practical recommendations.

Benefits

Among the benefits highlighted by the participants were the reduction in patient hospital stays, decreased bed occupancy, and reduced workload of hospitals. Interpretively, these benefits were often framed by participants as enhancing patient autonomy and reducing the stress associated with institutional care, suggesting that home-based care is valued not only for efficiency but for its impact on the patient’s lived experience. Offering home care services and providing frequent follow-up can lower the likelihood of disease recurrence and re-hospitalization. The findings of Weerahandi et al., Xiao et al., and Linertová et al. support these results, showing reduced readmission rates among home care patients19,20,21. It seems that post-discharge education for patients, their companions, and caregivers, along with raising awareness about the importance of follow-up treatments and addressing all healthcare needs by healthcare teams, are potential factors that may contribute to reducing readmission rates. However, some studies have reported mixed outcomes, with certain patient groups experiencing similar or even higher readmission rates due to variable home care quality or patient conditions22,23, indicating that context and implementation quality critically influence outcomes.

From the perspective of service recipients and their families, early discharge and receiving care at home enhanced their comfort, reduced their exposure to hospital infections, and improved satisfaction with care. Service providers, on the other hand, noted the increased opportunity for personalized and holistic care at home, which can lead to better therapeutic relationships and outcomes. Policymakers emphasized the potential for cost savings and system efficiency through reduced hospital strain and improved resource allocation. In this regard, the findings of Paskudzka et al. regarding post-discharge phone consultations indicated that these services were satisfactory for most patients, who felt comfortable and secure24. Moreover, the findings of a study conducted in New Zealand in 2004 indicated that the acceptance and satisfaction of patients and families with home care services were significantly higher than those with hospital care25.

Another benefit mentioned by the interviewees was the reduction in costs. Participants interpreted lower costs not only as economic savings but also as enabling more equitable distribution of healthcare resources. In this regard, research conducted in the United States in 2019 found that patients eligible for hospital-at-home care incurred lower costs compared to hospitalized patients under the U.S. Medicare system26. Palmer et al.27 also demonstrated in a retrospective cohort study in Canada that home care was associated with cost savings for both the patient and the hospital. Additionally, findings from another study in the U.S. indicated that home care costs for elderly patients were significantly lower compared to hospital-based care28. Yet, it is important to recognize that cost-effectiveness can vary widely depending on local health economics, insurance coverage, and resource allocation, which calls for cautious generalization of these findings across different settings.

The interviewees also referred to improvements in the quality of home care services. In this context, Ghaderi et al.29 showed that the average effectiveness of home care was higher than the average effectiveness of hospital admission. In interpreting this finding, the reason can be attributed to the allocation of more time by healthcare staff to patients, which not only results in better service delivery but also provides psychological comfort for patients. This highlights the importance of personalized care in home settings but also raises questions about workforce capacity and training that warrant deeper investigation.

Challenges

Regarding the identified challenges, from the perspective of policymakers, these findings underscore the need for clear governance, regulatory frameworks, and sustainable financing models. Service providers highlighted the absence of clear tariffs, lack of coordination with insurance companies, and the difficulty of providing care in uncontrolled home environments. Recipients emphasized poor public awareness and lack of cultural preparedness as key obstacles to effective home care.

One of the major challenges identified was policy-making and planning deficiencies for the provision of these services. In this regard, the findings of Shahsavari and colleagues revealed that policy-making methods could impact the delivery of health services to clients30. According to the study by Jarrin and colleagues, creating a database for home care, designing better care systems, developing managers at all levels, and addressing payment and policy issues are among the matters that should be considered to improve the quality of home care services31. The study by Daliri and colleagues indicated that the most effective interventions are those that focus on the collaboration between secondary and primary care by combining a specific post-discharge strategy13. However, this study adds critical insight into the instability of decision-makers and inconsistent supervision, issues less explored in previous research, suggesting a need for more robust governance structures.

The illegal and unregulated operation of home care centers was another key concern, echoing Alai et al.32. This issue remains under-addressed globally, and comparative analysis reveals that countries with clearer regulatory frameworks tend to report better care integration and safety, underscoring the necessity for legal reforms tailored to local contexts.

Another challenge in hospital-at-home care mentioned by the participants was the lack of sufficient financial resources and budgets. The budget allocation in the healthcare system is a very important and challenging issue. The way the budget is allocated to various organizations, programs, and actions reflects the government’s concerns and mindset towards solving the problems and issues in this field. In this regard, the study by Vali-Zadeh and colleagues identified several economic problems in providing home care services, including the high cost of hospital-at-home services, ineffective financial policies to support social workers and patients, the lack of coverage for care service costs by insurance organizations, the high cost of non-rentable medical equipment, and insufficient funding for home care service providers to offer technology-based services33.

Another challenge in hospital-at-home care, according to the participants in this study, was the failure to accurately define tariffs (unclear tariffs). Pricing healthcare services is one of the most important economic tools affecting access, efficiency, and the quality of health services. The participants in this study believed that tariffs for hospital-at-home care services had not been correctly defined, which could significantly impact the economic motivations of home care providers. This issue is influenced by factors such as the providers’ travel to the patient’s home, the time span different from hospital services, and the types of services and care needed at the patient’s home. The results of a 2020 study in the United States indicate that the use of home care services has been increasing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the findings of this study revealed that reforming payment systems to allow patient discharge for home care services is putting pressure on hospitals34.

Cultural and social barriers, including limited patient and family awareness and communication gaps, were raised by participants. They suggested that the patient’s family might not have adequate knowledge when interacting with the healthcare staff. This lack of awareness could lead to challenges in relationships between service providers and recipients. A study conducted on nurses working in hospital-at-home care centers revealed that the nurse providing home care should be qualified to conduct comprehensive care assessments, meaning they should be able to thoroughly assess the patient, the family, and the patient’s home to manage care effectively14. The findings of the study by Hestevik and colleagues in 2019 emphasized the importance of evaluation and planning, information and education, preparing the home environment, involving the elderly and caregivers, and supporting self-management in discharge and post-discharge care processes. Additionally, the study stressed that better communication between the service recipient, hospital providers, and home care providers is required to improve care coordination and facilitate recovery at home15. This study’s surface-level treatment of cultural challenges could be enriched by a comparative analysis of how different cultures affect acceptance and adherence to hospital-at-home programs, as well as strategies to overcome resistance rooted in cultural beliefs.

Overall, this study extends previous research by interpreting the experiential meanings attached to hospital-at-home care, showing how personal, social, and systemic dimensions intersect. These insights emphasize the importance of considering participants’ sense-making processes when designing, implementing, and evaluating home-based care programs.

Contribution to literature

This study contributes to the literature by offering a comprehensive, multi-perspective examination of hospital-at-home care benefits and challenges within a specific healthcare context, highlighting governance instability, regulatory gaps, and nuanced socio-cultural factors often overlooked in prior research. By integrating views of managers, providers, and recipients, it emphasizes the complex interplay between systemic, economic, and interpersonal factors that shape home care implementation.

Limitations and future directions

One of the major limitations of this study is its qualitative design, which may result in findings that are not easily generalizable across different cultural and geographical contexts, due to the influence of specific circumstances and the personal characteristics of the participants. The decision to use qualitative methods was intentional, as the aim of this study was to gain an in-depth, contextualized understanding of the benefits and challenges of hospital-at-home care from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders, which is best achieved through qualitative inquiry. Quantitative methods were not employed because the phenomenon under investigation required rich, descriptive data rather than numerical measurement at this stage of exploration. However, to enhance the generalizability and robustness of findings, future research is encouraged to employ mixed-methods approaches and longitudinal quantitative designs across diverse settings. These can help validate and build on the insights generated by this study. Moreover, in-depth exploration of cultural and legal barriers using comparative and cross-cultural methodologies would significantly advance understanding and inform more context-sensitive policy development.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support the view that hospital-at-home care services provide valuable benefits, such as reduced hospital burden, enhanced patient satisfaction, and improved care outcomes. At the same time, they reveal significant challenges that hinder the effective implementation of these services, including policy, financial, legal, and cultural barriers. We agree with the perspectives of our participants that hospital-at-home care can be a vital complement to conventional hospital services if properly supported by policy and infrastructure. Based on the findings, it is recommended that policymakers, healthcare administrators, and relevant stakeholders take targeted actions to address these challenges and optimize the delivery of hospital-at-home care.

Policy recommendations

To establish a solid foundation for the successful implementation of hospital-at-home care, it is crucial to begin with comprehensive planning that defines key elements such as target populations, service packages at different levels, service delivery processes, standardized tariffs, and an appropriate organizational structure. Once these components are outlined, the government must prioritize actions such as ensuring proper budget allocation, defining payment systems, coordinating with insurance companies, and facilitating collaboration with other healthcare organizations.

Workforce development

An essential step is to ensure the availability of a skilled workforce, including training and professional development for healthcare providers. It is critical to create incentive mechanisms to retain qualified staff and address the workforce-related challenges identified in the study.

Infrastructure and logistics

For hospital-at-home care to be sustainable, the necessary infrastructure must be expanded. This includes ensuring the availability of medical equipment, enhancing communication and data systems, and improving access to healthcare technologies in patients’ homes.

Implications for future research

The findings of this study suggest several areas for future research. For instance, more studies could explore the long-term effects of hospital-at-home care on patient outcomes and healthcare costs. Additionally, further research could focus on the integration of digital health tools to support hospital-at-home services and improve patient monitoring. Research into the socio-cultural barriers and facilitators for implementing hospital-at-home care, especially in diverse cultural settings, would also be valuable.

Data availability

All the data is presented as a part of tables. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Yusefi, A. R. et al. Responsiveness level and its effect on services quality from the viewpoints of the older adults hospitalized during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 653 (2022).

Abbasi, S., Sıcakyüz, Ç. & Erdebilli, B. Designing the home healthcare supply chain during a health crisis. Journal of Engineering Research. 11(4), 447–452 (2023).

Lawrence, J. et al. Home care for bronchiolitis: A systematic review. Pediatrics 150(4), e2022056603 (2022).

Levine, D. M. et al. Hospital-Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 172(2), 77–85 (2020).

Federman, A. D., Soones, T., DeCherrie, L. V., Leff, B. & Siu, A. L. Association of a Bundled Hospital-at-Home and 30-Day Postacute Transitional Care Program with Clinical Outcomes and Patient Experiences. JAMA Intern Med. 180(8), 1033–1041 (2020).

Hashemzadeh, Z., Habibi, F., Dargahi, H. & Arab, M. Explanation of the benefits and challenges of Home Care Plan after Hospital Discharge: a qualitative study. Payavard Salamat. 17(1), 34–44 (2023).

Nikmanesh, P., Arabloo, J. & Gorji, H. A. Dimensions and components of hospital-at-home care: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24(1), 1458 (2024).

Leff, B., DeCherrie, L. V., Montalto, M. & Levine, D. M. A research agenda for hospital at home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 70(4), 1060–1069 (2022).

Pandit, J. A., Pawelek, J. B., Leff, B. & Topol, E. J. The hospital at home in the USA: current status and future prospects. NPJ Digital Medicine. 7(1), 48 (2024).

Gaillard, G. & Russinoff, I. Hospital at home: a change in the course of care. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 35(3), 179–182 (2023).

Leong, M. Q., Lim, C. W. & Lai, Y. F. Comparison of Hospital-at-Home models: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 11(1), e043285 (2021).

Kanagala, S. G. et al. Hospital at home: emergence of a high-value model of care delivery. The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine. 35(1), 21 (2023).

Daliri, S. et al. The effect of a pharmacy-led transitional care program on medication-related problems post-discharge: A before—after prospective study. PLoS ONE 14(3), e0213593 (2019).

Jafarigol, M., Navipour, H. & Sadooghi-Asl, A. Care comprehensive assessment in home health care: Qualitative content analysis. Iran. J. Nurs. Res. 16(6), 24–32 (2022).

Hestevik, C. H., Molin, M., Debesay, J., Bergland, A. & Bye, A. Older persons’ experiences of adapting to daily life at home after hospital discharge: A qualitative metasummary. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19(1), 224 (2019).

Graneheim, U. H. & Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 24(2), 105–112 (2004).

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. Naturalistic inquiry (Sage Publications, 1985).

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E. & Moules, N. J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 16(1), 1609406917733847 (2017).

Weerahandi, H. et al. Home health care after skilled nursing facility discharge following heart failure hospitalization. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68(1), 96102 (2020).

Xiao, R., Miller, J. A., Zafirau, W. J., Gorodeski, E. Z. & Young, J. B. Impact of home health care on health care resource utilization following hospital discharge: a cohort study. Am J Med. 131(4), 395–407 (2018).

Linertová R, García-Pérez L, Vázquez-Díaz JR, Lorenzo-Riera A, Sarría- Santamera A. Interventions to reduce hospital readmissions in the elderly: in- hospital or home care. A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(6):1167–75.

Leff, B. & Burton, L. Home hospital programs: Promises and challenges in implementation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69(4), 897–905 (2021).

Kodama, R. T. & Rosenthal, J. A. Variability in Hospital-at-Home Programs and Its Impact on Patient Outcomes. Health Serv. Res. 57(2), 311–319 (2022).

Paskudzka, D. et al. Telephone follow-up of patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Early results. Kardiol. Pol. 78(7–8), 725–731 (2020).

McBride KL, White CL, Sourial R, Mayo N. Post discharge nursing interventions for stroke survivors and their families, J Adv Nurs; 2004: 47(2): 192–200.

Werner, R., Coe, N., Qi, M. & Konetzka, R. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern. Med. 179(5), 617–623 (2019).

Palmer, L. et al. A retrospective cohort study of hospital versus home care for pregnant women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 137(2), 180–184 (2017).

Frick, K. D. et al. Substitutive Hospital at Home for older persons: effects on costs. Am J Manag Care. 15(1), 49–56 (2009).

Ghaderi, H., Shafiee, H., Ameri, H. & Vafaeinasab, M. R. Cost-effectiveness of home care and hospital care for stroke patients. Quarterly Journal of Health Management. 4(3&4), 7–15 (2014).

Shahsavari, H., Nikbakht-Nasrabadi, A. R., Almasian, M., Heydari, H. & Hazini, A. R. Exploration of the administrative aspects of the delivery of home health care services: A qualitative study. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 17(1), 1 (2018).

Jarrin, O. F., Ali-Pouladi, F. & Madigan, E. A. International priorities for home care education, research, practice, and management: Qualitative content analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 73(1), 83–87 (2019).

Alaei, S., Alhani, F. & Navipour, H. Role of counseling and nursing care services centers in reducing work loads of hospitals: A qualitative study. Koomesh 19(2), 475–483 (2017).

Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., Saber, S. & Kianian, T. Challenges and barriers faced by home care centers: An integrative review. Medical - Surgical Nursing Journal 7(3), e83486 (2018).

Li, J., Qi, M. & Werner, R. M. Assessment of receipt of the first home health care visit after hospital discharge among older adults. JAMA Netw. Open 3(9), e2015470 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the doctoral thesis approved under project code no. 1401-3-37-24461 at Iran University of Medical Sciences. The researchers would like to thank all the participants who contributed to completing the questionnaires.

Funding

This study with code 1401–3-37–24461 was approved by the School of Health Management and Information Sciences of Iran University of Medical Sciences and was financially supported by this vice-chancellor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HAG and PN designed the study and prepared the initial draft. PN contributed to data collection and data analysis. HAG, JA, and PA have supervised the whole study and finalized the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is approved by the ethical committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences with the number of IR.IUMS.REC.1401.583. All the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikmanesh, P., Arabloo, J. & Gorji, H.A. Challenges and benefits of hospital-at-home care in Iran from providers and patients’ insights. Sci Rep 15, 44453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28052-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28052-z