Abstract

Bar substructures may be utilized for fixed full-arch implant-supported restorations, where suprastructures are cemented as prosthetic shells. Certain clinical situations may necessitate intraoral scanning of the bar substructures. However, the scannability and the accuracy of the intraoral scans remain unclear. This study aimed to compare and assess the scannability and the scan accuracy of two different bar materials used for implant-supported prostheses. Two maxillary implant-supported substructures (bars) were milled from 2 different materials. Group I from titanium and Group II from poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK). The substructures were digitized by using a desktop scanner (Medit MD-1D0410, Medit Corp). The STL file produced was considered the reference. Each substructure was scanned intraorally (n = 10) by using an intraoral scanner (IOS) (Medit i700; Medit Corp). The non-captured surface area in a preset time limit of 15 s (scannability) was assessed in (mm2). To evaluate the scanning accuracy, all STL files were imported into a surface-matching software program (Medit Design v3.0.6 Build 286; Medit Corp), where overall RMS (root mean square) deviations in (µm) were calculated. The Shapiro–Wilk test of normality was used. A comparison between the study groups was done by using an independent samples t-test. Significance was set at P < .05. The titanium substructure demonstrated better trueness and precision concerning deviation analysis (202.40 ± 27.57 and 197.50 ± 24.69, respectively) than the PEEK substructure (262.20 ± 30.87 and 244.1 ± 9.18, respectively) (P < .001). Regarding scannability, significantly more surface area was captured when scanning the PEEK substructure (985.42 ± 7.22) than titanium (951.15 ± 12.16) (P < .001). PEEK was more scannable. The titanium bar demonstrated significantly higher accuracy than the PEEK bar, which was more scannable than the titanium bar.

This trial, number NCT06423482, is registered at Clinical.gov. Its start date was May 14, 2024.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several factors can affect the accuracy of intraoral scanning, including the type of scanner, device calibration, scanning pattern, ambient illumination, humidity, and particular scanning conditions. The optical qualities of the digitized material surface also influence the scan accuracy1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 5725 standard, trueness and precision determine IOS accuracy6,17,17. While precision is the degree of agreement between independently measured values in a simulated environment representing the repeatability of measurements, trueness is the agreement between a test result and a known reference value6,18.

Scannability is defined as the ability of the surface of a material to be entirely scanned by a digital scanner in a specific time frame19. It is assessed by the calculated scanned/captured surface area for a specific surface/material in a predetermined time frame, measured in mm2/Sects19,20. It is affected by the material reflectiveness, translucency, surface texture, scanner type, surface treatment, wettability, and use of scanning aid materials21. Scannable materials are scanned without the need for a surface anti-reflective powder22,24,24.

Full-arch fixed implant-supported restorations can be constructed using various design options and materials. A feasible prosthetic option is a CAD-CAM milled suprastructure passively luted to a bar substructure. During the digital workflow of prosthesis construction, the CAD software program designs both supra and substructures. The software then reverse engineers the bar by extracting it from the original design25.

Studies have reported that scanning the bar after production, before suprastructure fabrication, improves passive fit and adaptation over the bar that may have undergone dimensional changes during machining25. Desktop scanners in the lab can be used for that purpose26,28,28.

In the clinical situation, the metal substructure is usually delivered with a PMMA suprastructure during the try-in phase25. Adjustments can be made to the polished surface of the metal substructure if necessary, and the PMMA suprastructures can be modified according to aesthetic and phonetic requirements, as well as occlusal relationships. The assembly can also be used temporarily by the patient until the final prosthesis is fabricated. Two intraoral scans are required in a fully digital workflow: One for the metal substructure and the other for the PMMA suprastructure that is placed on top of it29,30. Bar substructures can be made of different materials, commonly titanium and PEEK. While PEEK offers a lightweight, metal-free alternative with advantageous optical properties that can enhance scannability, titanium has traditionally been utilized for its strength and clinical reliability. Comparing their scanning accuracy and scannability is therefore relevant for optimizing digital full-arch implant workflows.

The scannability and accuracy of titanium and PEEK were previously tested19. Titanium exhibited higher trueness, while PEEK was more precise and more scannable than titanium. Previous studies have also reported that intraoral conditions moderately affected the precision and trueness of intraoral scanning31.

The scanning accuracy and scannability of the prosthesis substructure are essential to ensure a passively fitting suprastructure32. The present study compared the intraoral scanning accuracy and scannability of substructures fabricated from titanium versus PEEK19. The null hypothesis was that no significant difference would be found in the accuracy or the scannability between the 2 studied groups.

Methods

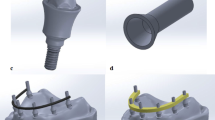

A maxillary edentulous patient having 4 osseointegrated implants (Vitronex Elite, Vitronex Implant system, Italy) was selected for the study. Multiunit abutments (MUA, Vitronex Elite) were selected, tightened, and torqued to the implants. Scan bodies (MUA Scan body, Vitronex Elite) were tightened to the abutments following the manufacturer’s guidelines. A chairside digital impression of the maxillary arch was made using an intraoral scanner (Medit i700; Medit Corp). A verification jig was made to verify the accuracy of the digital impression. A physical model of the virtual impression was 3D printed (Phrozen water-washable dental cast resin; Phrozen Tech Co, Ltd) by using resin (Phrozen Sonic Mini 4 K; Phrozen Tech Co, Ltd). A full arch screw-retained restoration was designed for the patient by using a CAD software program (Blender for Dental v3.6; Blender Foundation, B4D iBar™ module)33,34. A fully anatomic try-in was 3D printed (MAMMOTH 3D printer 6.6, V-Ceram Shop) from temporary resin material (Pro shape, Temp Resin, Turkey) as shown in Fig. 1. It was tried intraorally to verify esthetics and occlusion. The CAD design was then split into a bar substructure and suprastructure. The bar substructure had buccal and lingual finish lines with a width of 1 mm, as shown in Fig. 2.

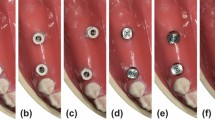

Two groups were formed based on the substructure material: PEEK (breCAM, BioHPP disk, Bredent GmbH & Co. KG, Senden, Germany) and titanium (dentatec, GmbH, Germany). The inter-arch space and the arch width allowed for a bar height of 5.1–6.6 mm occluso-cervically and a width of 5–6 mm buccolingually35,36. The STL file of the virtual substructure was exported for milling titanium and PEEK bars by using a milling machine (Roland DWX-52D Plus, Roland DGA Corporation). Bars were evaluated for passivity on the printed model, after which they were tried intraorally, as shown in Fig. 3. The one-screw test was used to ensure their passivity31.

Airborne-particle abrasion was used to roughen both bars using 50 μm Al2O3 (Aluminum oxide, Eisenbacher Dentalwaren; ED GmbH). Abrasion was completed at 0.2 MPa pressure from a 10 mm distance for 1 min31,34,37,38.

Accuracy assessment

Each bar substructure was scanned on the 3D-printed model by using a desktop scanner (Medit MD-1D0410, Medit Corp) to create a reference file STLR to be used as a control for each group, as shown in Fig. 4. Each bar was scanned 10 times intraorally by using an IOS (Medit i700; Medit Corp) according to the calculated sample size. Both groups followed the identical scan pattern, which began at the palatal surface, proceeded to the occlusal side, and terminated on the buccal side (P-O-B)39. A single experienced operator performed the scanning procedure to standardize the scanning speed, distance, and operator experience. Ambient light was adjusted to 1000 lx40.

The STLR file acquired from scanning the bar using the desktop scanner was used as a reference scan to evaluate trueness. Intraoral scans were aligned over the reference scan by using the best fit feature. The bar was selected as the reference. It was used to match its corresponding STLI, which was assigned as the target with the automatic alignment algorithm. To evaluate precision, deviations for all unique STL file pairings were calculated without repetition (45 comparisons). Each group included ten intraoral scans, resulting in 45 possible combinations. Then, 45 RMS values were obtained using the best-fit algorithm and three-dimensional comparison for each pair. The average of these 45 RMS values indicates the precision of a single group. Therefore, the precision of each group was determined19,41.

Accuracy was evaluated using a non-metrology grade software program (Medit Link Compare Tool, Medit Design v3.0.6, Build 286; Medit Corp), as shown in Fig. 5. For the quantitative assessment of 3D discrepancies between the target data STLI and the reference data STLR for both titanium and PEEK bars, the deviation display mode of the software was used to generate color-difference maps. From these maps, the overall root mean square (RMS) values were calculated and used for the statistical analysis of trueness and precision19,42,44,45,46,47,48,48, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The deviation threshold for green (representing minimal discrepancies) was set between − 50 μm and + 50 μm as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The minimum and maximum deviation ranges (green color) were set at −50 μm and + 50 μm, respectively42,43.

Scannability assessment

According to the Emam et al. technique, scannability was evaluated19. Titanium and PEEK bars were scanned individually to assess scannability. The minimum time in seconds necessary to thoroughly scan each bar was first calculated by intraorally scanning every bar. The PEEK bar was thoroughly scanned in 16 s, whereas the titanium bar required 20 s. The STL files of the thoroughly scanned bars were saved as a reference to evaluate scannability later on. A (T-1) approach was followed (reference) so that (T) was the time necessary to scan the most scannable bar material completely and defect-free (as PEEK was fully scanned in 16 s, it was used as the reference for calculating T). One second was subtracted from the estimated time T (T-1).

A scanning time limit of 15 s (T-1) was selected to evaluate each material’s sensitivity to rapid, complete, and defect-free scanning (scannability). The 2 substructures were scanned, each 10 times, every time in 15 s. With a total of 20 scans for both bars, the missing surface area for each substructure was determined after matching the STL file for every group with the missing fragments with the virtual reference STL file previously obtained for every group., The total surface area was 1000.739 mm2, as shown in Fig. 8. The Automatic alignment mode was chosen for superimposition (The Medit link compare tool, Medit Design v3.0.6, Build 286; Medit Corp), with the virtual design as the reference file and the scan in a predetermined time frame as the target file to measure the area of missing polygons (Fig. 8)19.

The reference file (virtual design) was used in STL format, while the tested file (bar) was used in PLY (Polygon File Format) to view the missing polygons easily after superimposition. The area of non-captured areas was calculated and tabulated19.

Sample size estimation was performed to allow statistical comparison with a study power of 80% and a significance level (α) of 0.05, based on the effect size (2.154) reported by Emam et al.19 a minimum of 10 digital scans per group was required. Accordingly, 20 scans were obtained (10 scans × 2 groups). All outcomes showed statistically significant differences, and post-hoc power analysis confirmed that the achieved power exceeded 95% for all comparisons, indicating that the sample size was sufficient to support the study findings.

Data were collected and statistically analysed with a statistical software program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v23.0; IBM Corp) 5. Normality was checked for all variables by using the Shapiro–Wilk test. All variables showed normal distribution, so means and standard deviation (SD) were calculated, and parametric tests were used. Comparisons between the 2 study groups were performed using an independent samples t-test to calculate adjusted means, standard error (SE), and 95% CIs. Significance was set at (P <.05). This trial is registered at Clinical.gov, NCT06423482, started May 14, 2024.

Results

The overall RMS in µm was used to represent precision and trueness. Deviation in trueness in the studied groups is presented in Table 1. The mean and standard deviation of trueness of the titanium bar (202.40 ± 27.57) were less than that of the PEEK bar (262.20 ± 30.87) (P <.001), with a significant difference. Deviation in precision in the different studied groups is presented in Table 1. The titanium bar was significantly more precisely scanned (197.50 ± 24.69) compared to the PEEK bar (244.1 ± 9.18) (P <.001), as shown in Fig. 9.

A scannability comparison between PEEK and titanium through the non-captured surface area (in mm2) in a predetermined time frame is presented in Table 2. The area of the scanned surface in a predetermined time frame of 15 s was significantly more in the PEEK group (985.42 ± 7.22) than in the titanium group (951.15 ± 12.16) (P <.001); PEEK was more scannable than titanium in a limited time frame, as shown in Fig. 10.

Discussion

This research indicates that the type of prosthodontic material significantly impacts scanning accuracy, as measured by trueness and precision, and scannability of the evaluated prosthodontic materials. Consequently, the null hypothesis was rejected.

In case of full-arch implant-supported bars, we may use intraoral scanners to scan the bar substructure49. However, prior research has demonstrated that, in contrast to in vitro scanning, the accuracy of dental arches in vivo was significantly reduced, affected by clinical conditions31,50.

The present clinical research investigated the influence of scanning various implant-supported prosthodontic substructure materials on their digitization accuracy and scannability.

The current findings indicate that PEEK displays enhanced scannability, whereas titanium achieves superior scan accuracy. These results emphasize the distinction between ease and speed of scanning (scannability) and the dimensional accuracy of the resulting digital model. Clinically, although PEEK’s optical properties may facilitate faster and smoother scanning, titanium’s higher accuracy remains critical for achieving precise prosthesis fit. Therefore, material selection should strike a balance between scanning efficiency and the accuracy required for definitive fabrication in full-arch implant workflows.

To ensure consistency and avoid potential confounding variables related to scanner type, all tests in this study were standardized using a single scanner.

If the bar was modified chairside, intraoral scanning captures this updated version32, reducing clinical steps and improving patient comfort. This approach also follows the manufacturer’s recommended protocol, which includes scanning the soft tissue first and then the bar in situ to optimize the gingival contours of the suprastructures51.

Several approaches are available to assess the 3D scan accuracy of a test scan compared to a reference. These include linear, angular distances, RMS deviation, and three-dimensional surface deviations, which are other methods to assess scan accuracy52,54,54. The current study used RMS values to compare the surface deviations of three-dimensional images, as they have been commonly used to evaluate scan deviations19,44,46,47,48,48, as it is beneficial. In measuring the overall accuracy of the scans55.

In this study, the virtual design of the bar was not used as a reference to eliminate the factor of difference in the milling of various materials as a variable. A desktop scan of the milled bar on the same model was used for each group to produce an independent reference19. Scanning powder was not employed to exclude the influence of coating thickness8. The PEEK bar recommended dimensions from previous literature were a minimum occlusal-cervical height of 5 mm, a minimum anterior buccolingual width of 4 mm, with an increase of width in the areas of the titanium sleeve for a minimum of 6 mm buccolingual width33,35,36. The patient’s inter-arch space and clinical situation allowed for a bar substructure design with an occlusal-cervical height of 5.1–6.6 mm and a buccolingual width of 5–6 mm. Buccal and lingual finish lines were created with a width of 1 mm to facilitate measurements and ensure a strong design for the suprastructure material, as shown in Fig. 2. Regarding the titanium bar, smaller dimensions would have been strong enough. However, the exact dimensions were adopted for the titanium bar substructure to standardise the size for both bars. According to reports, the automatic alignment algorithms provide the best possible repeatability43. They were therefore used in the present study.

Accurate scanning of the substructure is crucial, as any deviation at this stage is cumulatively transferred to the suprastructure, ultimately impacting its fit and overall prosthetic accuracy.

Airborne particle abrasion was used to improve the optical properties of bars used in this study and to avoid light reflections that the polished surface of the titanium bar might cause14.

The titanium framework showed significantly higher trueness and precision than PEEK. This may be attributed to its superior edge clarity, especially when surface-treated using airborne particle abrasion to decrease reflectivity. Revilla-León et al. have suggested that the dark color of the titanium scan body might be the cause6. These findings are supported by Baranowski et al.56 who stated that the titanium scan body group’s RMS value was lower than that of the PEEK scan body group.

Also, Azevedo et al.57, who indicated that the trueness and precision of titanium scanbodies were significantly superior to those of PEEK.

These results contradict those of Lee et al.12, and Lorenzo et al.10, who stated that PEEK intraoral scan bodies were more accurately scanned than titanium.

The properties of the surface that need to be scanned are a crucial element that may impact point cloud density. It is agreed that the optical properties of the material affect the number of points acquired13,15,22,23. In this study, PEEK exhibited better scannability than titanium, probably due to its matte, smooth, and opaque surface. This surface aids light absorption, enabling the scanner to create a denser point cloud. These optical features assist intraoral scanners in gathering additional data points with reduced disruptions, resulting in quicker and more comprehensive surface detection55,58. Those results align with Emam et al.19, who reported that PEEK was the most scannable material compared to titanium and PMMA. The findings of this investigation demonstrated that PEEK exhibited significantly higher scannability than titanium. Despite PEEK’s benefit in scannability, titanium demonstrated considerably higher accuracy in the final scans. These findings assure the significant difference between scannability concerning the ease and speed of scanning (scannability) and scan accuracy.

The study’s accuracy results are consistent with previously published ranges of whole arch digital implant scans, which show that the precision ranged from 15.2 to 204.2 μm and the trueness of digital implant impressions ranged from 7.6 to 731.7 μm47,55,58. To the authors’ knowledge, no study has evaluated the accuracy of intraoral scanning of full arch implant-supported substructures. Accordingly, those ranges were as close as possible.

This research contributes to clinical decision-making, as selecting the most accurately scanned bar material helps achieve highly passive suprastructures. This results in reduced marginal gaps, improved fit, and enhanced long-term serviceability of the final prosthesis. On the other hand, using materials with superior scannability offers significant clinical advantages by reducing chairside time and enabling faster and easier intraoral scanning. However, materials with lower scannability may not be as accurate, which could potentially affect the fit of the definitive restoration. Therefore, when less scannable materials are used, an experienced operator should perform the scanning procedure, utilizing efficient scanning strategies to optimize scan quality and minimize potential errors.

Blender for Dental CAD software program has introduced the I-bar module for designing an inner bar for full arch screw-retained restorations34. An inner bar has many benefits, including improving the prosthesis’s strength, providing greater options for suprastructure material selection, reducing weight, and avoiding excessive bulk in either the supra or substructures, improving comfort and esthetics for the patient34.

This study agreed with earlier research7,19,24,43. that reported that the results of a non-metrology grade software like Medit Link, the 50 μm threshold, are clinically relevant43. Further research is required to examine the impact of the difference in the 2 materials’ accuracy and scannability on the accuracy of the produced suprastructure.

This research presents several limitations. Using a single clinical case design inherently restricts the generalisability of the findings. However, this study design was intentionally chosen to facilitate a controlled comparison of the two substructure materials under the same clinical conditions. Intraoral variables, including mucosal colour, soft tissue reflectivity, salivary presence, temperature, humidity, and individual anatomical differences, can affect scan accuracy and the fit of prostheses. Limiting the study to one patient reduced inter-patient variability and allowed for a concentrated examination of the substructure material’s influence. Using only two materials for substructure (bar) fabrication limits the potential outcomes; incorporating additional materials could enhance the results.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

1.

Titanium bar scans showed higher Trueness and precision than PEEK.

-

2.

The PEEK bar substructure was more scannable than titanium and had the least non-captured surface area in mm2 in a predetermined time frame.

-

3.

There is no direct correlation between the scanning accuracy of substructure materials and their scannability; materials with high accuracy do not necessarily exhibit superior scannability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-XN1x6lElKgRZG_NAMZ1WViRpCR-XAzh/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=108567257312858837033&rtpof=true&sd=true

Abbreviations

- CAD-CAM:

-

Computer-aided design - computer-aided manufacture

- PEEK:

-

Poly-ether-ether-ketone

- IOS:

-

Intraoral scanner

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- PMMA:

-

Poly-methyl- methacrylate

References

Abduo, J. & Elseyoufi, M. Accuracy of intraoral scanners: A systematic review of influencing factors. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 26, 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1922/EJPRD_01752Abduo21 (2018).

Revilla-León, M. et al. Influence of ambient temperature changes on intraoral scanning accuracy. J. Prosthet. Dent. 130, 755–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2022.01.012 (2023).

Revilla-León, M. et al. Intraoral digital scans-Part 1: influence of ambient scanning light conditions on the accuracy (trueness and precision) of different intraoral scanners. J. Prosthet. Dent. 124, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.06.003 (2020).

Revilla-León, M., Subramanian, S. G., Att, W. & Krishnamurthy, V. R. Analysis of different illuminance of the room lighting condition on the accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of an intraoral scanner. J. Prosthodont. 30, 157–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13276 (2021).

Revilla-León, M., Subramanian, S. G., Özcan, M. & Krishnamurthy, V. R. Clinical study of the influence of ambient light scanning conditions on the accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of an intraoral scanner. J. Prosthodont. 29, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13135 (2020).

Revilla-León, M., Young, K., Sicilia, E., Cho, S. H. & Kois, J. C. Influence of definitive and interim restorative materials and surface finishing on the scanning accuracy of an intraoral scanner. J. Dent. 120, 104114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104114 (2022).

Persson, A. S., Odén, A., Andersson, M. & Sandborgh-Englund, G. Digitization of simulated clinical dental impressions: virtual three-dimensional analysis of exactness. Dent. Mater. 25, 929–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2009.01.100 (2009).

Kurz, M., Attin, T. & Mehl, A. Influence of material surface on the scanning error of a powder-free 3D measuring system. Clin. Oral Investig. 19, 2035–2043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1440-5 (2015).

Michelinakis, G., Apostolakis, D., Tsagarakis, A. & Lampropoulos, P. Influence of different material substrates on the accuracy of 3 intraoral scanners: A single-blinded in vitro study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 35, 82–93. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.7297 (2022).

Arcuri, L. et al. Influence of implant scanbody material, position and operator on the accuracy of digital impression for complete-arch: A randomized in vitro trial. J. Prosthodont. Res. 64, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2019.06.001 (2020).

Shely, A. et al. The influence of laboratory scanner versus intra-oral scanner on determining the implant axis by using three different scan abutments. Appl. Sci. 11, 8543 (2021).

Lee, J. H., Bae, J. H. & Lee, S. Y. Trueness of digital implant impressions based on implant angulation and scan body materials. Sci. Rep. 11, 21892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01442-9 (2021).

Holst, S., Persson, A., Wichmann, M. & Karl, M. Digitizing implant position locators on master casts: comparison of a noncontact scanner and a contact-probe scanner. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 27, 29–35 (2012).

Mizumoto, R. M. & Yilmaz, B. Intraoral scan bodies in implant dentistry: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 120, 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.10.029 (2018).

Rudolph, H., Quaas, S. & Luthardt, R. G. Matching point clouds: limits and possibilities. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 5, 155–164 (2002).

International Organization for Standardization ISO 10477. Dentistry d polymer-based crown and bridge materials. (2022). Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/80007.html

Arnold, C., Hey, J., Schweyen, R. & Setz, J. M. Accuracy of CAD-CAM-fabricated removable partial dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 119, 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.04.017 (2018).

International Organization for Standardization I-D-. D. I. D., - Part 1: Methods for Assessing Accuracy I, o. f. s. S. & 2023, H. w. i. o. s. H. A. F.

Emam, N. S., Khamis, M. M., Abdelhamid, A. M. & Ezzelarab, S. Digitization accuracy and scannability of different prosthodontic materials: an in vitro trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 130, 252e251. 252.e258 (2023).

Ritschl, L. M., Wolff, K. D., Erben, P. & Grill, F. D. Simultaneous, radiation-free registration of the Dentoalveolar position and the face by combining 3D photography with a portable scanner and impression-taking. Head Face Med. 15, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-019-0212-x (2019).

Alkadi, L. A. Comprehensive review of factors that influence the accuracy of intraoral scanners. Diagnostics (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13213291 (2023).

Nedelcu, R. G. & Persson, A. S. Scanning accuracy and precision in 4 intraoral scanners: an in vitro comparison based on 3-dimensional analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 112, 1461–1471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.05.027 (2014).

Lim, J. H. et al. A comparison of accuracy of different dental restorative materials between intraoral scanning and conventional Impression-Taking: an in vitro study. Mater. (Basel). 14, 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14082060 (2021).

Dutton, E. et al. The effect different substrates have on the trueness and precision of eight different intraoral scanners. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 32, 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12528 (2020).

Froimovici, F. O., Butnărașu, C. C., Montanari, M. & Săndulescu, M. Fixed full-arch implant-supported restorations: techniques review and proposal for improvement. Dent. J. (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12120408 (2024).

Maló, P. et al. Individual lithium disilicate crowns in a full-arch, implant-supported rehabilitation: a clinical report. J. Prosthodont. 23, 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.12137 (2014).

Nassar, H. I. & Abdelaziz, M. S. Retention of bar clip attachment for mandibular implant overdenture. BMC Oral Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02262-7 (2022).

Borga Donmez, M., Çakmak, G., Schimmel, M. & Yilmaz, B. Implementation of triple-scan protocol to evaluate the fit of complete-arch implant-supported fixed prostheses. J. Prosthodont. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13830 (2024).

Moglioni, E. et al. Intra-oral scanning and CAD/CAM prosthesis fabrication. Ann. Stomatol. 9, 146–161 (2018).

Papaspyridakos, P., AlFulaij, F., Bokhary, A., Sallustio, A. & Chochlidakis, K. Complete digital workflow for prosthesis prototype fabrication with double digital scanning: accuracy of fit assessment. J. Prosthodont. 32, 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13492 (2023).

Rutkunas, V. et al. In vitro and in vivo accuracy of full-arch digital implant impressions. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 32, 1444–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.13844 (2021).

Lin, W. S., Chou, J. C., Metz, M. J., Harris, B. T. & Morton, D. Use of intraoral digital scanning for a CAD/CAM-fabricated milled bar and superstructure framework for an implant-supported, removable complete dental prosthesis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 113, 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.01.014 (2015).

Maló, P. et al. Short-term report of an ongoing prospective cohort study evaluating the outcome of full-arch implant-supported fixed hybrid polyetheretherketone-acrylic resin prostheses and the All-on-Four concept. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 20, 692–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12662 (2018).

Scarano, A., Stoppaccioli, M. & Casolino, T. Zirconia crowns cemented on titanium bars using CAD/CAM: a five-year follow-up prospective clinical study of 9 patients. BMC Oral Health. 19, 286. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0988-x (2019).

Mijiritsky, E., Elad, A., Krausz, R., Ivanova, V. & Zlatev, S. Clinical performance of full-arch implant-supported fixed restorations made of monolithic zirconia luted to a titanium bar: A retrospective study with a mean follow-up of 16 months. J. Dent. 137, 104675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104675 (2023).

de Araújo Nobre, M., Moura Guedes, C., Almeida, R., Silva, A. & Sereno, N. Hybrid polyetheretherketone (PEEK)-acrylic resin prostheses and the all-on-4 concept: a full-arch implant-supported fixed solution with 3 years of follow-up. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072187 (2020).

Finger, C. et al. Effect of sandblasting on the surface roughness and residual stress of 3Y-TZP (zirconia). SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03492-6 (2020).

Jivraj, S. Graftless Solutions for the Edentulous Patient (Springer Nature, 2023).

Jamjoom, F. Z., Aldghim, A., Aldibasi, O. & Yilmaz, B. Impact of intraoral scanner, scanning strategy, and scanned arch on the scan accuracy of edentulous arches: an in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 131, 1218–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2023.01.027 (2024).

Button, H. et al. Scanning accuracy and scanning area discrepancies of intraoral digital scans acquired at varying scanning distances and angulations among 4 different intraoral scanners. J. Prosthet. Dent. 132, 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2023.01.025 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Influence of liquid on the tooth surface on the accuracy of intraoral scanners: an in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 31, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13358 (2022).

Wang, W., Yu, H., Liu, Y., Jiang, X. & Gao, B. Trueness analysis of zirconia crowns fabricated with 3-dimensional printing. J. Prosthet. Dent. 121, 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.04.012 (2019).

Yilmaz, B. et al. Influence of 3D analysis software on measured deviations of CAD-CAM resin crowns from virtual design file: an in-vitro study. J. Dent. 118, 103933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103933 (2022).

Andriessen, F. S., Rijkens, D. R., van der Meer, W. J. & Wismeijer, D. W. Applicability and accuracy of an intraoral scanner for scanning multiple implants in edentulous mandibles: a pilot study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 111, 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.07.010 (2014).

Ender, A. & Mehl, A. Accuracy of complete-arch dental impressions: a new method of measuring trueness and precision. J. Prosthet. Dent. 109, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3913(13)60028-1 (2013).

Hayama, H., Fueki, K., Wadachi, J. & Wakabayashi, N. Trueness and precision of digital impressions obtained using an intraoral scanner with different head size in the partially edentulous mandible. J. Prosthodont. Res. 62, 347–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2018.01.003 (2018).

Mangano, F. G., Veronesi, G., Hauschild, U., Mijiritsky, E. & Mangano, C. Trueness and precision of four intraoral scanners in oral implantology: A comparative in vitro study. PLoS One. 11, e0163107. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163107 (2016).

Mutwalli, H., Braian, M., Mahmood, D. & Larsson, C. Trueness and precision of three-dimensional digitizing intraoral devices. Int. J. Dent. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5189761 (2018).

Yilmaz, B. et al. Comparison of intraoral and laboratory scanners to an industrial-grade scanner while analyzing the fabrication trueness of polymer and titanium complete-arch implant-supported frameworks. J. Dent. 138, 104697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104697 (2023).

Flügge, T. V., Schlager, S., Nelson, K., Nahles, S. & Metzger, M. C. Precision of intraoral digital dental impressions with iTero and extraoral digitization with the iTero and a model scanner. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 144, 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.017 (2013).

https://support.medit.com/hc/en-us/articles/360020924592--colLab-The-substructure-of-an-implant-bar., M. h. c. c. T. s. o. a. i. b. o. A. a.

Flügge, T. et al. The accuracy of different dental impression techniques for implant-supported dental prostheses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 29 (Suppl 16), 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.13273 (2018).

Sezer, T., Esim, E. & Yılmaz, E. Trueness of intraoral scanners in different scan patterns for Full-Arch digital implant impressions. J. Oral Implantol. 50, 426–430. https://doi.org/10.1563/aaid-joi-D-24-00054 (2024).

Sezer, T., Yılmaz, E. & Esim, E. Comparison of intraoral scanning modes in three distinct Full- arch digital implant impression scenarios: an in vitro study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 39, 217–222. https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.10882 (2024).

Ciocan, L. T. et al. Comparative analysis of four different intraoral scanners: an in vitro study. Diagnostics (Basel Switzerland). 14, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14131453 (2024).

Baranowski, J. H., Stenport, V. F., Braian, M. & Wennerberg, A. Effects of scan body material, length and top design on digital implant impression accuracy and usability: an in vitro study. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 17, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2025.17.3.125 (2025).

Azevedo, L. et al. Influence of implant scanbody material and intraoral scanners on the accuracy of Complete-Arch digital implant impressions. Int. J. Prosthodont. 37, 575–582. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.8565 (2024).

Zhang, Y. J., Shi, J. Y., Qian, S. J., Qiao, S. C. & Lai, H. C. Accuracy of full-arch digital implant impressions taken using intraoral scanners and related variables: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Implantol (Berl). 14, 157–179 (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**N.S.E.:** Writing, Investigation, Editing, Conceptualisation, Original draft preparation, Methodology, Software.**N.A.M.:** Supervision, Investigation, Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, and Data curation.**M.M.K.:** Supervision, Investigation, Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualisation, Methodology, and Data curation.All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent for sharing clinical data and images for scientific purposes was collected from all patients prior to commencement of the study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Alexandria University ethics review committee) with approval reference number of 0796_11/2023.

Consent for publication

“Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.”

Informed consent

for sharing clinical data and images for scientific purposes was collected from all patients prior to commencement of the study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Alexandria University ethics review committee) with approval reference number of 0796_11/2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Emam, N.S., Metwally, N.A. & Khamis, M.M. Influence of substructure material on the scanning accuracy and scannability of implant-supported full arch bar substructures. Sci Rep 15, 43110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28419-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28419-2