Abstract

Fresnel incoherent correlation holography (FINCH) is a widely used incoherent digital holography technique. FINCH has a higher lateral resolution but a lower axial resolution compared to those of direct imaging methods with the same numerical aperture. The low axial resolution problem of FINCH was addressed by developing sectioning FINCH methods implemented by pixel-by-pixel electronic scanning of a phase pinhole to achieve sectioning capability in FINCH, mimicking a conventional confocal microscope. The above approach requires not only an additional spatial light modulator for electronic scanning but also time-consuming data acquisition and processing. In this study, for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, we developed a fully computational sectioning method for FINCH. This computational optical sectioning FINCH (COS-FINCH) exploits the axial intensity and phase characteristics of FINCH holograms and first and second order derivatives of axial intensity distributions to identify the object planes, extract information, and achieve sectioning. Extensive simulation studies and results of preliminary experimental studies are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Incoherent digital holography (IDH) has a rich history evolving with new knowledge and capabilities alongside the development of optical, computational, and material technologies over more than half a century1,2,3. Fresnel incoherent correlation holography (FINCH), developed in 2007, is one of the widely accepted IDH methods for both advanced research and applications. In FINCH, a light from an object point is divided into two, differently modulated using two quadratic phase masks and interfered to create a self-interference hologram4. At least three holograms with phase-shifts θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians between the two interfering object waves are recorded and combined to remove the twin image and bias contributions in the hologram. A complex hologram obtained by superposing the above phase-shifted holograms when numerically propagated reconstructs the object images at different planes without the above-mentioned noises. In the first demonstration of FINCH, the generation of two object waves was achieved using randomly multiplexed diffractive lenses with different focal lengths displayed on a spatial light modulator (SLM). This first version of FINCH experienced a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to scattering noises from the random multiplexing. Further, it required at least three camera recordings with a temporal resolution of one-third of that of direct imaging systems, and also a low axial resolution compared to that of direct imaging methods. Despite the above disadvantages, at that point in time, FINCH was a fast, robust, and simple scanning-free IDH method compared to its predecessors, such as optical scanning holography5, conoscopic holography6, triangle interferometers7, and rotational shearing interferometers1. Therefore, FINCH was rapidly adopted into a fluorescence microscope module, resulting in a powerful fluorescence holographic microscope8.

After these developments, in 2011, during continued research on FINCH, a polarization multiplexing approach was developed9, and subsequently, the surprising super-resolution capability of FINCH was revealed10. FINCH can surpass the Lagrange invariant condition and achieve a lateral resolution that is about 1.5 times better than that of a direct imaging system with the same numerical aperture (NA)1. The topic of FINCH has attracted more research activities from researchers around the world1. Researchers have been focused on both improving the performance of FINCH and utilizing FINCH instead of direct imaging methods for applying other imaging technologies. Spatial and polarization multiplexing methods were developed to achieve single-camera shot capability and improve the temporal resolution of FINCH11,12,13,14. Novel optical modulators such as birefringent lenses were developed for implementing FINCH with a high SNR15,16. FINCH was implemented in the framework of coded aperture imaging to achieve a single camera shot17. Recently, deep learning methods were developed to achieve single camera shot capability in FINCH18. In the other direction, FINCH was used as a platform for implementing other imaging techniques such as structured illumination19, scattering-assisted super-resolution20, multidimensional polarization imaging21, and a deep-learning-based IDH system22.

Researchers also focused on developing techniques to tune the axial characteristics of FINCH. The depth of focus (DoF) requirement of FINCH or any imaging system is dependent upon the nature of the application. For instance, if the goal of the application is to record a sparse scene of samples along the entire depth with the least number of camera shots, then a high DoF is desirable. If a dense scene of samples is imaged, then it is necessary to image with a low DoF and a high axial resolution so that every plane can be observed without the background noise from other planes. In the first experimental studies in 201110 and a later thorough fundamental study based on Lagrange invariant conditions on FINCH23, the higher DoF property of FINCH compared to that of direct imaging systems with the same NA was revealed. There were several studies, with some focused on extending the DoF of FINCH24 and some focused on improving the axial resolution of FINCH25. Notable studies in this direction are the development of confocal FINCH26 and FINCH with sectioning capabilities27,28,29. A novel optical sectioning configuration of FINCH was proposed, mimicking a conventional confocal microscope but using electronic scanning by a phase pinhole displayed on an SLM27. While this method achieved performance close to that of conventional confocal systems while retaining the super-lateral resolution of FINCH, the requirement of two SLMs and time-consuming data acquisition and processing precluded the application of the above methods to commercial FINCH fluorescence microscopes.

In this study, we propose and demonstrate a fully computational approach for sectioning in FINCH. Unlike direct imaging, in IDH, including FINCH, the complex hologram contains the complete 3D location information of objects. By numerical backpropagation, the different planes of the object are reconstructed. By observing the intensity and phase distributions reconstructed along the propagation direction and the first and second order derivatives of axial intensity, for every pixel across the hologram reconstruction matrices, it is possible to detect the planes and transverse locations that contain object information. The intensity distribution of hologram pixels peaks at the propagation distances that contain the object image. The phase values are quasi-uniform in those regions and different from those of the rest of the pixels. Utilizing the above intensity and phase signatures, depth-specific object information can be extracted without the influence of background information constituted by images from the other depths. During this research, we also observed the existence of inherent focusing errors of FINCH holograms. When a thin binary object is imaged, it is expected that the intensity distribution across all the transverse pixels peaks at the image plane. However, in FINCH, it was observed that the intensity distribution for different hologram pixels peaked at different propagation distances even for thin objects. Some transverse pixels exhibited multiple intensity peaks in the vicinity of the image plane, with local and global maxima, and with the global maxima not overlapping with the image plane. Based on the above observations, we developed the computational optical sectioning FINCH (COS-FINCH). COS-FINCH does not require any change to the standard experimental setup for recording FINCH holograms, but only involves a slightly longer post-processing to achieve sectioning. In this first study, cases where the object information from different planes does not overlap transversely are considered due to practical and realistic illumination of samples.

The rest of the manuscript is divided into four sections. The methodology is presented in the next section. A simulation study starting from the generation of FINCH holograms to the cross-sectioning procedure is presented in the third section. Preliminary results of the experimental study of COS-FINCH are discussed in the fourth section. The study is summarized, and challenges and future perspectives are presented in the final section.

Methods

The optical configuration of FINCH with a polarization multiplexing scheme is shown in Fig. 1. Light from an object point with an amplitude of \(\:\sqrt{{I}_{o}}\) is polarized at 45o with respect to the active axis of the SLM by a linear polarizer P1, collected and modulated by a refractive lens L with a focal length f1 at a distance of zs from the object point. The complex amplitude of light just before the SLM is given as \(\:{C}_{1}\sqrt{{I}_{o}}Q\left(1/{z}_{s}\right)Q\left(-1/{f}_{1}\right)\), where \(\:Q\left(a\right)=\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}\left(i\pi\:{ar}^{2}/\lambda\:\right)\), \(\:r=\sqrt{{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}}\) and C1 is a complex constant. The light from the refractive lens is incident on an SLM, which is located in tandem with the refractive lens for simplified mathematical analysis. At the SLM, two beams are created with orthogonal polarizations; one modulated by the phase mask displayed on the SLM (Φ = 0) and another unmodulated by the SLM (Φ = 90o). On the SLM, a diffractive lens with a focal length of \(\:{f}_{2}=\:\)zh/2 is displayed, where zh is the distance between the SLM and the image sensor. The complex amplitude of light after the SLM is given as \(\:{C}_{2}\sqrt{{I}_{o}}Q\left(1/{z}_{s}\right)Q\left(-1/{f}_{1}\right)\left\{{1}^{\perp\:}+{Q\left(-1/{f}_{2}\right)}^{\parallel\:}\right\},\) where the symbols \(\:\perp\:\) and \(\:\parallel\:\) represent polarizations that are perpendicular and parallel to the active axis of the SLM, respectively, and C2 is a complex constant. Between the SLM and the image sensor, a second linear polarizer P2 is positioned oriented at 45o with respect to the active axis of the SLM to create interference between the waves modulated and the unmodulated by the SLM. After the polarizer P2, the components of the two fields: \(\:{C}_{2}\sqrt{{I}_{o}}Q\left(1/{z}_{s}\right)Q\left(-1/{f}_{1}\right) \otimes Q\left(\frac{1}{{z}_{h}}\right)\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\sqrt{{I}_{o}}Q\left(1/{z}_{s}\right)Q\left(-1/{f}_{1}\right)Q\left(-1/{f}_{2}\right) \otimes Q\left(\frac{1}{{z}_{h}}\right),\) oriented by polarizer P2, interfere creating a self-interference pattern, where ‘\(\: \otimes\)’ is a 2D convolution operator. This self-interference pattern for a point is the point spread hologram (PSH) of FINCH, given as

where \(\:{\bar{r}}_{0}=\left(u,v\right)\) is the location vector in the sensor plane.

A 2D object consisting of M points can be expressed as a collection of delta functions

where bj is the intensity of the j-th point. From the properties of linearity and shift invariance, the object hologram for a multipoint object O is given as

From Eqs. (1)-(3), the object hologram can also be expressed as

As seen from the construction of Eq. (4), the object’s image cannot be reconstructed directly from the raw hologram due to the presence of the twin image and bias noises. To remove those noises, at least three phase-shifted object holograms are needed with phase differences θk = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians for k = 1 to 3, between the two interfering object waves. The phase of the diffractive lens displayed on the SLM is given as \(\:Q\left(-1/{f}_{2}\right)\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}\left(i{\theta\:}_{k}\right)\). The complex hologram is given as

The image of the object at different planes can be reconstructed by numerically propagating the complex hologram to different distances zr, given as

The intensity at every transverse pixel (x,y) reconstructed along zr peaks at the image planes, which can be identified by calculating the first and second order derivatives given as \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\) and \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\) when they are 0 and negative values at the peak point, respectively. The phase distribution within the area of a thin object is expected to be quasi-uniform over the image area at the transverse plane and different from the rest of the pixels at the reconstructed image plane. Therefore, \(\:{\phi\:}_{R}=arg\left\{{H}_{OH} \otimes Q\left(\frac{-1}{{z}_{r}}\right)\right\}\) can reveal valuable information for the extraction of a plane-specific image. In addition to the above intensity and phase characteristics, a space constraint is applied to the image planes to limit the processing area. The COS-FINCH is implemented by utilizing the pixel-wise variation of the above three parameters, namely first and second order derivatives of reconstructed intensity and reconstructed phase, and prior knowledge of the finite lateral extension of the objects at the different planes. In this study, we consider only cases where images at any two different planes do not transversely overlap.

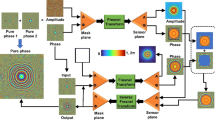

Optical configuration of FINCH with polarization multiplexing scheme. The regular numerical back propagation of the FINCH hologram reconstructs images from different planes. With the COS-FINCH approach involving intensity, phase, and space constraints, the information from other planes is removed computationally.

Simulation studies

A simulation study of FINCH was carried out using MATLAB. A matrix size of 250 pixels along x and y directions, wavelength λ = 650 nm, pixel size Δ = 20 μm, distances zs = 40 cm, zh = 80 cm, focal lengths of the refractive lens f1 = 40 cm and of the diffractive lens on the SLM f2 = 40 cm, were used with a polarization multiplexing scheme.

FINCH hologram as a diffractive lens

A FINCH hologram of a scene or an object indeed contains the 3D location information of an object. However, when the object is a single point along the optical axis at the origin (x, y)=(0,0), a FINCH hologram behaves as a diffractive lens. With recent research on employing computational algorithms to convert a complex function into a phase-only function and rapid developments in advanced manufacturing methods, realizing the above FINCH lens is not distant30,31,32,33,34. Here, the axial imaging characteristics of the FINCH hologram for a point are compared with those of a diffractive lens with the same focal length. For the above FINCH configuration, for a single point located at zs = 40 cm, it is reconstructed by numerical back propagation to a distance zr = 40 cm. A diffractive lens with a focal length f = 40 cm (in addition to the refractive lens of f1 = 40 cm) was simulated for comparison. The images of the FINCH holograms of a point simulated for θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians are shown in Figs. 2(a)-2(c), respectively. The magnitude and phase of the complex FINCH hologram are shown in Figs. 2(d) and 2(e), respectively. The phase image of the diffractive lens used for comparison is shown in Fig. 2(f). It has already been established in the previous studies that for FINCH, the two-point resolution is better than that of direct imaging, but for a single point, there is no difference10. The plot of line data of the focal spot at zr = 40 cm for FINCH and imaging with a diffractive lens is shown in Fig. 2(g). The zr value was changed from 30 cm to 50 cm, and the intensity distribution was simulated. The line data for the FINCH hologram for a point and a diffractive lens are shown in Fig. 2(h). It can be seen that the FINCH hologram has a slightly higher DoF compared to that of a diffractive lens. This is due to the non-uniformity of the magnitude of the hologram, unlike a diffractive lens whose magnitude is uniform, and therefore, this difference in DoF is not unique to FINCH. The non-uniform magnitude gives rise to a smaller bunch of rays that can maintain the focus of the image over a longer distance compared with that of the uniform case, with a larger bunch of rays that produces a blurred image. The FWHM values of the axial plot for FINCH and the diffractive lens in Fig. 2(h) are 4.6 cm and 4.2 cm, respectively.

Axial characteristics of FINCH hologram of two points at two depths

The simulation was repeated for two points located at two different depths zs (point object 1) = 35 cm and zs (point object 2) = 40 cm, and two different transverse locations (x = 0, y = 0) and (x = 25, y = -25). The images of the FINCH holograms for θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians are shown in Figs. 3(a)-3(c), respectively. The magnitude and phase of the complex FINCH hologram are shown in Figs. 3(d) and 3(e), respectively. The FINCH hologram was numerically propagated to zr = 37.8 cm and 40 cm, and the reconstructed images are shown in Figs. 3(f) and 3(g), respectively. The FINCH hologram was numerically propagated from zr = 20 cm to 60 cm, and the value at two locations corresponding to the location of the two points was obtained, and their line data are plotted in Fig. 3(h). As it is seen from Fig. 3(h), the two points are reconstructed at their respective planes as expected. The FWHM values of the axial plots for FINCH for zs = 35 cm and 40 cm in Fig. 3(h) are 6.4 cm and 4.4 cm, respectively. One interesting observation is that the case–point object 1 that does not satisfy the optimal FINCH condition experiences a slightly lower axial resolution compared to the case–point object 2 that satisfies the perfect FINCH condition23. Note that although the reconstruction distance of object 2 is longer than that of object 1, unlike a regular lens, its DoF is shorter than that of object 1, and in this sense, FINCH is different than a regular bifocal lens.

FINCH holograms with phase-shifts (a) θ = 0, (b) θ = 2π/3 and (c) θ = 4π/3. (d) Magnitude and (e) phase of the complex hologram. (f) Phase image of a diffractive lens. (g) Line plot at (x = 0) of the focus intensity, for FINCH hologram for a point and a diffractive lens. (h) Axial intensity of the FINCH hologram for a single point and of a diffractive lens.

FINCH holograms for two points at two depths, zs = 35 cm and 40 cm, and two transverse locations (x = 25, y = -25) and (x = 0, y = 0) pixels with phase-shifts (a) θ = 0, (b) θ = 2π/3, and (c) θ = 4π/3. (d) Magnitude and (e) phase of the complex hologram. Reconstruction at (f) zr = 37.8 cm and (g) zr = 40 cm. (h) Axial characteristics of FINCH hologram for (x = 0, y = 0) and (x = -25 and y = 25).

Axial characteristics of FINCH hologram of two objects at two depths

Next, two square-shaped objects with a size of 10 × 10 pixels are considered located at the above two planes, zs = 35 cm and 40 cm, at two different transverse locations. The images of the simulated FINCH holograms corresponding to phase shifts θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians and the magnitude and phase of the complex hologram formed are shown in Figs. 4(a)-(e), respectively. The reconstructed images at the two planes corresponding to the reconstruction distances zr = 37.8 cm and 40 cm are shown in Figs. 4(f) and 4(g), respectively. The intensity variation along the axial direction for every pixel for object 1 located at zs = 35 cm and object 2 located at zs = 40 cm is shown in Figs. 4(h) and 4(i), respectively. The Figs. 4(a)-4(g) are as expected. However, the axial plots for every pixel of the object are not as expected when comparing them with Fig. 3(h). Unlike a single point, for an object consisting of multiple points, multiple peaks occur in the vicinity of the reconstruction distance. We believe that the above effect is due to the nature of incoherent light. The FINCH holograms are formed by self-interference, where light from each object point is split into two parts: differently modulated and interfered. There is no mutual interference, as light from two different points cannot interact, resulting in an intensity summation at the image sensor. At the image sensor, the FINCH hologram is a summation of numerous Fresnel zone plates, such as intensity distributions, each with a slightly different quadratic phase depending upon the location of the object point. However, the reconstruction is similar to that of a coherent case with a single numerical Fresnel propagation. This results in slightly different reconstruction distances for different object points, even though the object is a thin object located at a single plane. This effect, in addition to other experimental errors such as shift and alignment errors, can worsen the focusing errors. However, further fundamental studies on FINCH and IDH are needed to fully understand the above behaviors. This behavior does not favor the computational extraction of information corresponding to a single plane, especially when the planes are close to each other along z. Comparing Figs. 4(h) and 4(i), it can be seen that there is an overall shift of the axial curve depending upon the location of the object. The phase images obtained from the FINCH holograms at planes corresponding to object 1 and object 2 are shown in Figs. 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. The phase distributions for the above two cases along the axial direction are simulated, and their plots are shown in Figs. 5(c) and 5(d), respectively. The phase distributions converge to a single value at the two reconstruction distances. However, there is still some uncertainty as the phase values of object 1 may match those of object 2 at both planes. Therefore, an additional limited support constraint may be needed to extract the image plane-wise without any background noise and contributions from images of the other planes.

FINCH holograms for two squares shaped (10 × 10 pixels) objects at two depths zs = 35 cm and 40 cm and two transverse locations (x = 0, y = 0) and (x = 30, y = -30) pixels with phase-shifts (a) θ = 0, (b) θ = 2π/3 and (c) θ = 4π/3. (d) Magnitude and (e) phase of the complex hologram. Reconstruction at (f) zr = 37.8 cm and (g) zr = 40 cm. Axial intensity characteristics of FINCH hologram for (h) object 1 and (i) object 2. The different color lines indicate different pixels within the object.

COS-FINCH for two plane objects

A dual-plane object consisting of two smiley objects, Object 1 and Object 2, each (50 × 50 pixels) from two different planes, zs = 35 cm and 40 cm, and two non-overlapping transverse locations is considered as shown in Fig. 6(a) and 6(b), respectively. The magnitude and phase of the complex FINCH hologram formed by the superposition of the raw holograms corresponding to θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 are shown in Figs. 6(c) and 6(d), respectively. In all these figures, colormap turbo has been selected as it has the highest dynamic range compared to other colormaps of MATLAB. The two objects were reconstructed for zr = 37.8 cm and 40 cm. The intensity and phase images obtained at zr = 37.8 cm are shown in Figs. 6(e) and 6(f), respectively. The intensity and phase images obtained at zr = 40 cm are shown in Figs. 6(g) and 6(h), respectively. While Figs. 6(e) and 6(g) show the focused and blurred objects, the other figures, namely Figs. 6(f) and 6(h), show a constant phase over the reconstructed in-focus object lines. The cube data sets (250 × 250 × 100) pixels > 6 Megapixels, consisting of the 2D intensity and phase distributions for different values of zr are shown in Figs. 6(i) and 6(j), respectively. The propagation distance of 20 cm was sampled by 100 points with a resolution of 2 mm.

Test objects (a) Object 1 at plane 1 (zs = 35 cm) and (b) Object 2 and plane 2 (zs = 40 cm). (c) Magnitude and (d) phase of the complex FINCH holograms of the two objects. (e) Intensity and (f) phase distributions obtained at zr = 37.8 cm. (g) Intensity and (h) phase distributions obtained at zr = 40 cm. Cube data (250 × 250 × 100) pixels of (i) intensity and (j) phase along zr = 30 to 50 cm each. Limited support constraint applied at (k) zr = 37.8 cm and (l) zr = 40 cm. Results of computational sectioning at (m) zr = 37.8 cm and (n) zr = 40 cm for object 1 and object 2, respectively.

The line data of intensity \(\:{I}_{R}=\left|{H}_{OH} \otimes Q\left(-\frac{1}{{z}_{r}}\right)\right|\:\)and phase \(\:{\phi\:}_{R}=arg\left\{{H}_{OH} \otimes Q\left(\frac{-1}{{z}_{r}}\right)\right\}\) along zr for every pixel (x,y) was extracted, analyzed and the following line data: \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\) and \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\) were created. At the reconstruction distances zr = 37.8 cm and 40 cm, a boundary of ± 1 cm was set to capture the maxima in intensity by observing the values \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\) and \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\:\)for 0 and negative values, respectively. The phase value was noted at the reconstruction distances zr = 37.8 cm and 40 cm within the region of the objects that were focused. A boundary of 0.5 to 1 rad was set, and the central value was − 1.78 radians. The boundary was 1 rad based on the range of phase values within the object. Only pixels that have phase values within this range are extracted. In addition to the above constraints, a limited support constraint based on the sizes of the two objects was applied at the optimal reconstruction distances of the two objects. The constraint masks used for Object 1 and Object 2 at the corresponding reconstruction distances are shown in Figs. 6(k) and 6(l), respectively. The computationally sectioned images are shown in Figs. 6(m) and 6(n) corresponding to the two reconstruction distances. It is seen from the sectioned images that there is certain pixel information missing, which is due to the intrinsic focusing errors of FINCH holograms, as they did not fit within the above intensity, phase, and space constraints. There are also unexpected advantages in this approach. FINCH holograms have intrinsic reconstruction noise, as an incoherent hologram is reconstructed by coherent back propagation, as shown in Figs. 6(e) and 6(g). A closer observation reveals that the sectioned images are much cleaner than the ones obtained directly from FINCH. Considering the fact that experimentally recorded FINCH holograms have higher noise levels, the developed COS-FINCH is expected to remove noise and generate cleaner reconstructed images.

Experiments

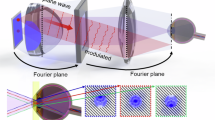

A standard polarization multiplexing FINCH experimental setup was built as presented in9. The schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 7. A spatially incoherent LED source (M660L4, Thorlabs) with a spectral width of 20 nm around a central wavelength of 660 nm was used. The light from the LED was propagated through two refractive lenses, L1 and L2, with focal lengths of 7.5 cm and 5 cm, respectively, with a linear polarizer P1 in between them. The linear polarizer P1 was oriented at 45o with respect to the active axis of the SLM. Two objects, digit ‘2’ and digit ‘4’ from Group 3 of the negative USAF resolution target, were used one after the other at distances of 5 cm and 5.75 cm from L3 with a focal length of 5 cm and recorded. The object was critically illuminated, and the light from the object was collected by a refractive lens L3. The light modulated by L3 was incident on a beam splitter and on a reflective phase-only SLM with 1920 × 1200 pixels and a pixel pitch of 8 μm (Exulus HD2 Thorlabs). A quadratic phase mask with a focal length of 10 cm, with phase shifts θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians, was displayed on the SLM. A monochrome image sensor with 1440 × 1080 pixels and a pixel size of 3.5 μm was mounted at a distance of zh=20 cm from the SLM. Nearly half of the light that is along the active axis was modulated by the SLM, and both modulated and unmodulated light were passed through another linear polarizer, P2, oriented at 45o with respect to the active axis of the SLM. The light modulated by the SLM interferes with the unmodulated light after the polarizer P2. A bandpass filter with a central wavelength of 633 nm and a spectral width of 5 nm was used before the image sensor to improve the fringe visibility.

The proof-of-concept experimental studies were carried out exactly as discussed in the previous studies9. Most 3D experimental demonstrations of FINCH used two standard objects from two different optical channels at two different distances from the lens L3, combined using a beam splitter. In this case, the FINCH holograms of the two objects were summed in the image sensor. In this study, the FINCH holograms for the two objects were recorded independently and summed in the computer to avoid the complications of two-channel experiments. This also allows for controlling the relative strengths of the two objects with higher precision than two-channel experiments. In FINCH, a spatially incoherent and temporally coherent light source is used, resulting in two effects, namely, self-interference and intensity summation. Self-interference occurs for light from the same object point, and a summation of intensities occurs for light from different object points. When two objects are simultaneously present at two depths and recorded, the two FINCH holograms of the two objects, consisting of the above two effects, are summed at the image sensor. In this study, the FINCH holograms of the two objects were recorded independently and digitally summed on a computer. The only difference is the place of summation, whether it is an image sensor or a computer, while preserving the physics of the study. The nonlinearity that may arise at the detector due to the extremely different strengths of the two objects can be avoided by using objects of similar sizes. The challenges with the dynamic ranges of image sensors can be mimicked by adjusting the strengths of the two holograms before summation.

The FINCH holograms for the two object digits ‘4’ and ‘2’ for phase shifts θ = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3 radians are shown in Figs. 8(a)-8(c), respectively. The magnitude and phase of the complex hologram formed by the superposition of the recorded holograms are shown in Figs. 8(d) and 8(e), respectively. The reconstructed intensity and phase at plane 1 corresponding to a reconstruction distance zr = 8 cm are shown in Figs. 8(f) and 8(g), respectively. Once again, colormap ‘turbo’ was selected to have an extended dynamic range to clearly observe the background noise. The reconstructed intensity and phase at plane 2 corresponding to a reconstruction distance zr = 10 cm are shown in Figs. 8(h) and 8(i), respectively. From Figs. 8(f)-8(i), it is seen that at any plane, only one of the objects is focused, with the second object appearing blurred. The focused object has visible background noise contributed by the blurred image of the other out-of-focus image. The phase images show that there is a significant phase contrast between the reconstructed images and the background, and mild phase contrast between the two images. Within the object that is in focus, the phase distribution is quasi-uniform. Therefore, by applying a set of constraints in intensity distributions along zr and its derivatives, phase and space constraints, it is possible to extract a plane-specific image without the influence of noise from blurred images from other out-of-focus planes.

FINCH holograms of two object digits ‘2’ and mirrored ‘4’ separated by 7.5 mm axially for phase shifts (a) θ = 0, (b) θ = 2π/3, and (c) θ = 4π/3 radians. (d) Magnitude and (e) phase of the complex hologram. Reconstructed (f) intensity and (g) phase at zr = 8 cm. Reconstructed (h) intensity and (i) phase at zr = 10 cm.

The step-by-step procedure of COS-FINCH is presented next. The flow chart of the COS-FINCH procedure is presented in Fig. 9. Four sets of cube data (1080 × 1080 × 50) pixels (~ 60 Megapixels) were obtained by propagating the complex FINCH hologram for different values of zr: Intensity and phase distributions for zr = 7 cm to 9 cm for object 1 digit ‘4’, and intensity and phase distributions for zr = 9 cm to 11 cm for object 2 digit ‘2’. The space constraint exactly matches the sizes of the two objects – object 1, x: 581 to 720 pixels, y: 341 to 440 pixels, and object 2, x: 441 to 625 pixels, y: 471 to 605 pixels. The images of the limited support constraint applied at plane 1 zr = 8 cm and plane 2 zr = 10 cm are shown in Fig. 10. The phase range constraint of 1 rad was applied around a central value of -2 radians, and the pixels that had phase values outside this range were set to 0. The above constraints were applied in addition to the search for local maxima on the axial intensity curves, namely the first and second derivatives of the intensity distributions. As seen from Fig. 6, the reconstruction is not free of aberrations, as some of the pixels do not satisfy the above constraints. The extracted images were averaged pixel-wise, replacing the pixel value with the average of the pixel value and the eight neighboring pixel values. The extracted object information corresponding to plane 1 digit ‘4’ is shown in Fig. 11(a). As seen from the figure, the background noise has been completely removed. FINCH holograms have reconstruction noise, such as any holographic imaging system, contributed by noise from optical components, active elements such as SLMs, light sources, external optical and electronic noise, detector noise, and even uncompensated twin image and bias noise due to changes between recordings, as shown in Figs. 8 and 11. The noise levels are visually amplified via the colormap ‘turbo’ of MATLAB for better visualization. To have a reliable comparison, the extracted object information is compared with the reconstruction result of a hologram that contains only the object information of plane 1 digit ‘4’ as shown in Fig. 11(b). A mask constraint was applied to have a reliable comparison when calculating the figure of merit. From Figs. 11(a) and 11(b), it is seen that the computational cross-sectioning has a better performance than the reconstruction of the FINCH hologram containing only object 1 digit ‘4’. The entropy values of Figs. 11(a) and 11(b) are 0.13 and 0.18, respectively. The procedure was repeated for the second plane for object 2 digit ‘2’. A similar performance was noticed for the second object, also when compared with the reconstruction of the FINCH hologram containing only object 2 digit ‘2’. The entropy values of Figs. 11(c) and 11(d) are 0.24 and 0.31, respectively. The above promising values of the figure of merit indicate that the performance will be much better when compared to multiplane objects. The computational sectioning time for plane 1 with 140 × 100 (14000) pixels was 28.24 s in MATLAB (version 2022a) using a computer with 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-11700 @ 2.50 GHz processor with 32 GB RAM. The computational sectioning time for plane 2 with 184 × 134 (24656) pixels was 50.29 s. From the above sectioning times, it can be seen that the proposed method is significantly faster than the optical scanning and confocal approaches reported in previous studies.

After sectioning and before the averaging, it was found that certain pixels that do not fit within the intensity, phase, and space constraints are not recovered. The recovered image of object 1 digit ‘4’ before averaging is shown in Fig. 12(a), which shows many missing pixels. Two pixels, namely the missed pixel (363,695) and recovered pixel (361,678), are shown in Figs. 12(b) and 12(c), respectively. The plots of IR, \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\) and \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\) as a function of zr for the missed pixel and recovered pixel are shown in Figs. 12(d)-12(f) and 12(g)-12(i), respectively. The missed pixel is well within the space constraint and so passed the first filter. As seen from Figs. 12(d)-12(i), the missed pixel corresponds to an axial intensity distribution with a long focusing error. The global maxima of axial distribution IR for zr = 7 to 9 cm for the missing pixel occurs far away at zr ≈ 9 cm from the expected reconstruction distance zr = 8 cm. Consequently, the second constraint \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\) does not generate 0 at this point, as seen in Fig. 12(e), and therefore this pixel was not included. Only after passing this filter, the phase constraint was applied, and as seen above, in this case, it is not relevant. Regarding the recovered pixel, it is well within the space constraint. The global maxima of IR occurred as expected at zr = 8 cm and subsequently met the first and second derivative constraints. The final step of the phase constraint was also met as the phase value at this pixel was − 1.9 radians, which is close to the central value − 2 radians. Therefore, the recovered pixel met all three spaces, intensity, and phase constraints and was included.

(a) Extracted object information by computational sectioning of plane (1) (b) Reconstruction result of FINCH hologram containing only object 1, mirrored digit ‘4’. (c) Extracted object information by computational sectioning of plane (2) (d) Reconstruction result of FINCH hologram containing only object 2 digit ‘2’.

(a) Image of the extracted object 1. (b) Image with missed pixel information and (c) recovered pixel information. Plots of (d) IR, (e) \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\), (f) \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\) for the missed pixel. Plots of (g) IR, (h) \(\:\frac{d{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{z}_{r}}\), (i) \(\:\frac{{d}^{2}{I}_{R}(x,y)}{d{{z}_{r}}^{2}}\) for the recovered pixel.

Conclusion and future perspectives

We proposed and demonstrated a FINCH-based computational optical sectioning method termed COS-FINCH. COS-FINCH utilizes the intensity and phase characteristics of FINCH holograms along the reconstruction distance and prior knowledge of the object distributions in the transverse direction to identify and extract the object information plane-wise. The cube data sets, namely the intensity and phase along every pixel (x,y), are extracted along the reconstruction distances and processed by applying space, intensity, and phase constraints. The extracted information is free of background noises contributed by blurred object information from other planes and also intrinsic FINCH reconstruction noises. It must be noted that even for FINCH systems with higher environmental noise, it is possible to filter out noise as long as the noise does not exhibit the same axial characteristics as the signal. However, further studies are needed to fully understand the noise tolerance level of COS-FINCH with different types and strengths of external noise. The computational sectioning time is dependent upon the size of the object, with 28 and 50 s for the two test objects, which are much faster when compared to the previous optical confocal FINCH methods that required several hours per plane27. The performance of COS-FINCH is affected by the FINCH system specifications. When the NA is increased, the axial resolution increases, which improves the performance of COS-FINCH. The proposed COS-FINCH is not void of disadvantages. The reconstruction of the object along certain transverse pixels of the FINCH hologram exhibits unusual focusing behaviors, with the intensity distribution not reaching peak values at the corresponding reconstruction distances, and does not exhibit a phase value as the other pixels within the object boundaries. These errors cause dark pixels within the extracted object. This has been solved by averaging the extracted image over a few pixels. The averaging process, in turn, slightly degrades the lateral resolution of FINCH, which is a minor penalty for achieving a fully computational cross-sectioning in FINCH. However, in the near future, this challenge will be addressed.

The second challenge is related to the applicability of COS-FINCH. Unlike the previous studies27,28, where the optical sectioning FINCH was implemented on objects at two depths but overlapping transversely, COS-FINCH has been demonstrated only for non-overlapping cases. While the above can be partly attributed to the optical configuration employed in this study, the phase, space, and intensity constraints may not be sufficient to extract object information for overlapped cases, especially when the objects are axially closer. Further studies are needed with improved constraints to extract object information without the noise from objects present in other planes. However, given the simplicity of the approach, the developed COS-FINCH is expected to benefit FINCH, other IDH techniques, and other 3D imaging methods. We believe that the developed method will be useful for imaging biological samples that are susceptible to scattering noises.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Rosen, J. et al. Recent advances in self-interference incoherent digital holography. Adv. Opt. Photonics. 11, 1–66 (2019).

Tahara, T. et al. Roadmap of incoherent digital holography. Appl. Phys. B. 128, 193 (2022).

Rosen, J. et al. Roadmap on recent progress in FINCH technology. J. Imaging. 7, 197 (2021).

Rosen, J. & Brooker, G. Digital spatially incoherent Fresnel holography. Opt. Lett. 32, 912–914 (2007).

Poon, T. C., Wu, M. H., Shinoda, K. & Suzuki, T. Optical scanning holography. Proc. IEEE 84, 753–764 (1996).

Sirat, G. & Psaltis, D. Conoscopic holography. Opt. Lett. 10, 4–6 (1985).

Kim, S. G., Lee, B. & Kim, E. S. Removal of bias and the conjugate image in incoherent on-axis triangular holography and real-time reconstruction of the complex hologram. Appl. Opt. 36, 4784–4791 (1997).

Rosen, J. & Brooker, G. Non-scanning motionless fluorescence three-dimensional holographic microscopy. Nat. Photonics. 2, 190–195 (2008).

Brooker, G., Siegel, N., Wang, V. & Rosen, J. Optimal resolution in Fresnel incoherent correlation holographic fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Express. 19, 5047–5062 (2011).

Rosen, J., Siegel, N. & Brooker, G. Theoretical and experimental demonstration of resolution beyond the Rayleigh limit by FINCH fluorescence microscopic imaging. Opt. Express. 19, 26249–26268 (2011).

Tahara, T., Kanno, T., Arai, Y. & Ozawa, T. Single-shot phase-shifting incoherent digital holography. J. Opt. 19, 065705 (2017).

Nobukawa, T., Muroi, T., Katano, Y., Kinoshita, N. & Ishii, N. Single-shot phase-shifting incoherent digital holography with multiplexed checkerboard phase gratings. Opt. Lett. 43, 1698–1701 (2018).

Quan, X., Matoba, O. & Awatsuji, Y. Single-shot incoherent digital holography using a dual-focusing lens with diffraction gratings. Opt. Lett. 42, 383–386 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Dynamic 3D Fresnel incoherent correlation holography imaging based on single-shot mirrored phase-shifting technology. Opt. Lett. 49 (20), 5886–5889 (2024).

Siegel, N., Lupashin, V., Storrie, B. & Brooker, G. High-magnification super-resolution FINCH microscopy using birefringent crystal lens interferometers. Nat. Photonics. 10, 802–808 (2016).

Liang, D., Zhang, Q., Wang, J. & Liu, J. Single-shot Fresnel incoherent digital holography based on geometric phase lens. J. Mod. Opt. 67, 92–98 (2020).

Vijayakumar, A. et al. Fresnel incoherent correlation holography with single camera shot. Opto-Electron Adv. 3, 08200004 (2020).

Huang, T. et al. Single-shot Fresnel incoherent correlation holography via deep learning based phase-shifting technology. Opt. Express. 31, 12349–12356 (2023).

Kashter, Y., Vijayakumar, A., Miyamoto, Y. & Rosen, J. Enhanced super resolution using Fresnel incoherent correlation holography with structured illumination. Opt. Lett. 41, 1558–1561 (2016).

Kashter, Y., Vijayakumar, A. & Rosen, J. Resolving images by blurring: superresolution method with a scattering mask between the observed objects and the hologram recorder. Optica 4, 932–939 (2017).

Tahara, T. Polarization-filterless polarization-sensitive polarization-multiplexed phase-shifting incoherent digital holography (P4IDH). Opt. Lett. 48, 3881–3884 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Deep learning-based incoherent holographic camera enabling acquisition of real-world holograms for holographic streaming system. Nat. Commun. 14, 3534 (2023).

Rosen, J. & Kelner, R. Modified Lagrange invariants and their role in determining transverse and axial imaging resolutions of self-interference incoherent holographic systems. Opt. Express. 22, 29048–29066 (2014).

Nobukawa, T., Katano, Y., Muroi, T. & Ishii, N. Bimodal incoherent digital holography for both three-dimensional imaging and quasi-infinite–depth-of-field imaging. Sci. Rep. 9, 3363 (2019).

Bulbul, A., Hai, N. & Rosen, J. Coded aperture correlation holography (COACH) with a superior lateral resolution of FINCH and axial resolution of conventional direct imaging systems. Opt. Express. 29, 42106–42118 (2021).

Siegel, N. & Brooker, G. Improved axial resolution of FINCH fluorescence microscopy when combined with spinning disk confocal microscopy. Opt. Express. 22, 22298–22307 (2014).

Kelner, R., Katz, B. & Rosen, J. Optical sectioning using a digital Fresnel incoherent-holography-based confocal imaging system. Optica 1, 70–74 (2014).

Kelner, R. & Rosen, J. Parallel-mode scanning optical sectioning using digital Fresnel holography with three-wave interference phase-shifting. Opt. Express. 24, 2200–2214 (2016).

Choi, K. H., Yim, J. & Min, S. W. Optical defocus noise suppressing by using a pinhole-polarizer in Fresnel incoherent correlation holography. Appl. Opt. 56, F121–F127 (2017).

Gopinath, S. et al. Enhanced design of multiplexed coded masks for Fresnel incoherent correlation holography. Sci. Rep. 13, 7390 (2023).

Khonina, S. N., Kazanskiy, N. L. & Butt, M. A. Grayscale lithography and a brief introduction to other widely used lithographic methods: A state-of-the-art review. Micromachines 15, 1321 (2024).

Aderneuer, T., Fernández, O. & Ferrini, R. Two-photon grayscale lithography for free-form micro-optical arrays. Opt. Express. 29, 39511–39520 (2021).

Grushina, A. Direct-write grayscale lithography. Adv. Opt. Technol. 8, 163–169 (2019).

Geng, Q., Wang, D., Chen, P. & Chen, S. C. Ultrafast multi-focus 3-D nano-fabrication based on two-photon polymerization. Nat. Commun. 10, 2179 (2019).

Funding

The authors thank the funding agencies, European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme Grant Agreement No. 857627 (CIPHR), DP240103231 from the Australian Research Council, and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) Grant No. 3306/25 for supporting this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Idea-V.A, Supervision-J. R, Experiments - V.A, Main manuscript - V.A, Theory of FINCH - J. R, Figures - V. A, Analysis - J. R, Calculations - J. R. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anand, V., Rosen, J. Computational optical sectioning in Fresnel incoherent correlation holography. Sci Rep 15, 45209 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29281-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29281-y