Abstract

Equine-Assisted Services (EAS) encompass a range of therapeutic interventions utilizing equine interactions to achieve therapeutic goals. This study explores heart rate synchronization between horses and riders during mounted and unmounted interactions, focusing on its potential implications for emotional regulation. A total of 25 participants aged 6–12 took part in the study, which included two groups: novice riders diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (n = 15) and experienced neurotypical riders (n = 10). Heart rate measurements were obtained using Polar® Equine and Verity Sense Optical Heart Rate Sensors. Results indicate mutual heart rate synchronization between horses and riders, suggesting a potential mechanism for emotional regulation. The neurotypical group showed high levels of synchronization, suggesting that rider experience influences the physiological connection between horse and rider., while notably, children with ADHD demonstrated above-average synchronization by their fourth to sixth EAS session. These findings underscore the significance of EAS in promoting physiological and emotional well-being, particularly for individuals with ADHD. This study contributes to the understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying therapeutic effect of EAS interventions and highlights their potential in clinical practice. Further research is needed to examine the mechanisms, stability, and therapeutic significance of horse-human physiological synchronization over time, including how synchronization patterns evolve with rider experience and influence therapeutic outcomes in children with ADHD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The effects of horse-human interactions have been studied extensively, with a growing body of research examining how these interactions influence both human and equine participants. While much of the literature has focused on human outcomes, several studies have also assessed physiological responses in horses including heart rate, cortisol levels, and heart rate variability (HRV) to better understand the mutual nature of this interaction.) 1. The heart rate is innervated by the brain as it stimulates the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The ANS is divided into the Sympathetic system which leads to increased heart rate and to the Parasympathetic system which decreased the heart rate. Ideally, a successful rhythmic interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches allows the heart to adapt to physical and emotional needs, leading to decreased stress and anxiety, improved mental and physical performance, and a more synchronized connection between the heart and the brain1. Both heart rate and HRV represent the interaction between vagal and sympathetic regulation, and serve as indicators for measuring stress and autonomic balance across species, including humans and animals2,3.

In addition to indicating stress levels, heart rate serves as an internal bodily signal integral to the process of interoception. Interoception involves the nervous system sensing, interpreting, and integrating internal signals from the body. These signals encompass sensations such as heartbeat, hunger, thirst, breathlessness, and the urge to urinate. In essence, interoception is the body’s mechanism for monitoring its internal state and maintaining homeostasis, or internal balance4. This process also plays a crucial role in emotional experience, self-awareness, and bodily regulation. It contributes to how we experience emotions, as many emotional states are closely linked to physical sensations. For example, anxiety might be associated with a racing heart, while calmness might be linked to slower, more regular breathing5.

Physiological heart rate synchronization holds clinical significance as it seems to be connected to emotional bonding, particularly among humans. Synchronization refers to the process where two systems (in this case, the heart rates of the rider and the horse) align or operate in unison6 Therefore, heart rate synchronization between humans and animals is important for bonding which enhances the health and well-being of both1. One study has found similar heart rates between humans and horses during mounted riding, although the sample size was small n = 6 9. A few other studies including older adults have found a synchronization of heart rhythms between horses and human heart rhythms during unmounted activities such as grooming and while being handled by a person on ground1,7,8. These studies have found for example that engaging with a horse in an unmounted activity raised participants heart rate and HRV9. As HRV is a biomarker for autoregulation, these results may indicate a better cardiovascular function and better emotional balance compared to low HRV levels that might indicate the present of stress1.

One might hypothesize that the horse-human interaction and synchronization is an important mechanism that affects Equine Assisted Services (EAS), a variety of multimodal and complex activities and therapies, designed for achieving therapeutic goals through interaction of clients with equines10. EAS has been shown to have a positive effect on humans in various life areas including physically and emotionally11. For example, it was found that equine-assisted interventions can reduce symptoms of anxiety, hyperarousal, and emotional dysregulation among individuals diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a diagnosis that is characterized by high stress level12,13,14. In addition to decreasing anxiety, horse-human interaction has been associated with improved self-perception, increased emotional awareness, and a greater sense of safety through the development of non-verbal, affective communication and physical contact with the animal15. The interaction with the horse involves a tactile and physical touch which releases endorphins within the nervous systems and facilitate anxiety. The touch arouses positive emotions such as being loved while giving the sense of confidence16. These outcomes highlight the therapeutic potential of EAS in fostering emotional regulation and resilience in trauma-exposed populations.

To date, the horse-human synchronization has not been explored among neurotypical children and among children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) that are commonly referred for EAS therapy. ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder is characterized by the presence of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity symptoms17,18 as well as emotional impulsiveness, deficient emotional self-regulation, anxiety, depression, aggressive behavior, and lower self-efficacy. Self-regulation is the ability to recognize and control one’s behavior, emotions and general mood, and is needed for everyday functioning and daily living19. These emotional problems and deficits in psychological functions can lead to significant difficulties in academic achievements, as well as in social and personal relationships20.

Studies have found that participants of EAS, diagnosed with ADHD were less aware of internal bodily signals and were less able to regulate and monitor their own behavior, and therefore may have less interoceptive awareness4. Since difficulties in interoceptive processing are associated with conditions such as anxiety and depression, enhancing interoceptive awareness is a common therapeutic goal to improve emotional regulation and overall mental well-being21.

Research goals

EAS have been associated with a wide range of positive outcomes in physical, emotional, and social domains. However, despite the growing body of research supporting their effectiveness, the underlying mechanisms through which EAS exert their effects are not yet fully understood. One potential mechanism of interest is physiological synchronization between humans and horses, which may play a role in emotional regulation and stress reduction. This question is particularly relevant in the context of ADHD, a common referral group for EAS interventions. Children with ADHD often experience challenges in self-regulation and interoception, areas potentially influenced by human–horse physiological interaction. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore heart rate synchronization during a riding session among two distinct groups of children: experienced neurotypical riders and novice riders diagnosed with ADHD. We hypothesized that the phenomena of synchronization between horses and humans will be present regardless of diagnosis or experience. Therefore, two groups were selected to explore heart rate with the aim of identifying patterns of physiological coordination within each group with the hope to gain insight into whether synchronization can serve as a marker of therapeutic engagement and regulation, even in early stages of EAS participation.

Methods

Study design

This study used a Correlational study design.

Participants

The study comprised of two convenience sample groups. The first group (ADHD group) included 15 horses and novice participants (5 boys, 10 girls; mean age = 11 year, SD 1.41) diagnosed with ADHD who were referred to EAS by their pediatrician. Inclusion criteria for the ADHD group were as follows: (1) children between 6 and 12 years of age; (2) diagnosis of ADHD from a medical professional based on DSM-5 criteria, with or without medication (e.g., psychostimulant medication); (3) general doctors’ approval and referral for participation in EAS; (4) within their 4-6th riding session. Exclusion criteria applied to the ADHD group were as follows: (1) moderate to severe cognitive impairment; (2) neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy); (3) children with additional developmental disorders (e.g., Autism, Cerebral Palsy); (4) children with severe sensory loss (e.g., blindness).The ADHD group was matched with 15 horses (10 males, 5 females), aged 9 to 20 years (M = 13.0 years).The second group (neurotypical group) comprised 10 horses and neurotypical experienced participants (10 girls; mean age = 10.50, SD 1.08). Inclusion criteria for the neurotypical group were as follows: (1) children between 6 and 12 years of age; (2) general doctors’ approval for participation in riding sessions; (4) riding experience of between two to three- years. Exclusion criteria applied to the neurotypical group were as follows: (1) ADHD diagnosis; (2) moderate to severe cognitive impairment; (3) neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy); (4) children with additional developmental disorders (e.g., Autism, Cerebral Palsy); (5) children with severe sensory loss (e.g., blindness) The neurotypical group rode 10 of these horses (6 males, 4 females), aged 9 to 20 years (M = 14.4, SD = 4.2). All horses had a minimum of three years of experience participating in EAS at the same facility, ensuring familiarity with the therapeutic context and minimizing variability related to equine behavior or training level. A flow diagram summarizing the recruitment, eligibility screening, group allocation, and final inclusion of participants is presented in Fig. 1.

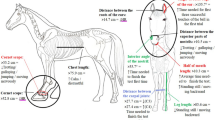

Measures

The primary physiological variable measured in this study was heart rate. Heart rate data were collected from both children and horses using Polar® heart rate monitoring systems designed for equine and human use, respectively. The software of “Polar Flow” was used to collect and present the data with no filters used.

Demographic questionnaire-designed for this specific study

Polar®equine sensor: The Polar® Equine heart rate monitor for riding includes the Polar® H10 heart rate sensor and the Polar Equine heart rate belt for riding. It is designed to measure the horse’s heart rate levels during exercise and monitor their resting and recovery heart rate (Polar Global, 2024). The Polar® equine sensor has been used previously to measure and monitor horses heart rate22.

Polar® Verity Sense Optical Heart Rate Sensor: this sensor was used to measure the participants heart rate as it measures the pulse through the participants skin (Polar Global, 2024).

Procedure

After obtaining ethical approval, relevant participants were approached to participate in the study. All participants were recruited from the same stable. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians prior to participation in the study. Once the consent form was signed by child and parents, parents completed the demographic questionnaire, participants from the ADHD group filled out the SCARED questionnaire that was administered by a research assistant who did not take part of the intervention measurement. After filling the questionnaire, participants took part in a single recorded session, conducted during their fourth to sixth EAS session and were evaluated throughout the session. The novice ADHD group participants each rode a horse they have been riding with in their first 4 sessions. The neurotypical group rode the horse they have been riding for the past year. Both groups underwent the same five minutes of unmounted following 25 min of riding session and measurement. Although sessions were conducted according to a general structure that included sequential walk, trot, canter, and then a final walk phase, durations of each gait varied slightly based on the rider’s abilities and therapeutic goals. While efforts were made to maintain consistency, the interaction was not strictly standardized across participants.

Participants received and wore an arm sensor while the equine sensor was tacked on the horse. Both Sensors measure heart rate and were synchronized to one another. Measurement began while the horse and participant were not present together for the first minute and then proceeded for approximately 30 min. During these 30 min participants engaged with their horses, mounted and rode in different paces including: walk, trot and canter. At the end participants dismounted the horses and the last minute included measuring the heart rate while participants and horses were apart from each other. All assessments were administered by two research assistants blinded to the participant’s group allocation.

There were no missing data in this study. All 25 participants completed the full riding session and produced complete heart rate recordings. Both equine and human sensors maintained continuous signal quality throughout the measurement period. No dyads were excluded due to data loss or equipment failure.

Human ethics statement

All methods and protocols used were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval has been obtained from the Tel Aviv University Institutional Review Board (IRB ethical committee, number 0003949-3), and all methods were approved and carried out in accordance with the IRB guidelines The study has also been registered in the Clinical Trials.gov, and has been assigned (identifier number NCT05869253), first registration at 22/5/2023.

Animal ethics statement

The experiment with equines was approved by IRB No:0003949-2. All methods were approved and carried out in accordance with the IRB guidelines and ARRIVE guidelines for reporting research involving animals. Horses in the study were horses owned by Mount Judea stable for at least five years at the time of the study.

Statistical analysis

Initially, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for each of the child-horse pairs to assess the association between their heart rates. The rationale was to check for a straightforward linear link between the two heart rates, which might indicate a synchronized physiological response. In order to investigate the temporal dynamics of the relationship, cross-correlation functions were estimated for each child-horse pair across lags from 0 to 5 s. The rationale was to detect time-shifted relationships in which one partner’s heart rate might systematically precede (or follow) fluctuations in the others.

Recognizing the importance of stationarity for time series inference, we formally assessed each series using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, confirming that many were non-stationary. To investigate potential predictive relationships without imposing differencing or strict distributional assumptions, Granger causality tests were performed on each pair using block permutation methods, which account for both non-standard asymptotic distributions and possible departures from normality23,24. In Granger causality, one time series is said to predict (or “Granger-cause”) another if including its past values significantly improves predictions of the other series’ future, relative to a baseline model using only the latter series’ past. This approach was deemed suitable as the study aims to go beyond simple associations and timing overlaps, exploring whether one signal can systematically forecast changes in the other. While the method, like the previous approaches considered, does not establish true causation, it is particularly useful when investigating the directionality of influence or interplay in time series data such as physiological signals, where one might theorize that fluctuations in a child’s heart rate could precede, or be preceded by, corresponding shifts in the horse’s physiological state. We address this by testing Granger causality in each direction (child to horse, horse to horse or both), considering either as exhibiting significant Granger causality.”

A block permutation approach was used to account for the non-standard asymptotic distributions without altering the data’s inherent structure (rather than differencing the series). This method preserves local temporal dependencies by segmenting the time series into blocks of consecutive observations and shuffling these blocks (of size 5 in our case), thus maintaining the integrity of the time series. After computing the original Granger causality test statistics for each pair, repeated block permutations produced a null distribution of the test statistics. The proportion of permuted statistics that exceeded the observed statistic formed an empirical p-value. This procedure allows one to assess whether the predictive relationship is stronger than would be expected by chance, all while maintaining the original signal’s structure within blocks (accounting for potential trends or irregularities in the signals, avoiding artificially differencing the data).

Finally, an additional permutation test was conducted across pairs to evaluate the statistical significance of the proportion of pairs exhibiting significant Granger causality, comparing the observed results to those obtained under random pairings, thus providing a second layer of hypothesis testing. This second-level test shuffled the child-horse pairings themselves and recomputed the fraction of significant pairs. By repeating this process many times, a null distribution of the “percentage of significant pairs” was constructed, reflecting the scenario in which there is no meaningful child-horse pairing.

Results

Child and horse heart rate data

To illustrate the raw data and the apparent synchronization that motivated further statistical investigation, Fig. 2 presents two example time series from Observation 5 (child-horse dyad number 5 from the Neurotypical group) and Observation 19 (child-horse dyad number 5 from the ADHD group). The figure shows simultaneous measurements of the horse’s heart rate (dashed lines) and the child’s heart rate (solid lines) during a riding session over the course of approximately 30 min. A visual inspection reveals that each dyad’s two time series tend to move in a roughly coordinated manner, with rises and falls that appear to occur at similar times or in overlapping intervals.

It is important to note that this apparent correspondence does not by itself constitute any proof of synchronization, nor does it establish any predictive or causal mechanism. Instead, this example underscores why more rigorous approaches, such as correlation analysis, cross-correlation, and Granger causality, were pursued.

Correlation and cross-correlation analysis

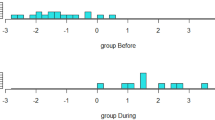

The correlation analysis aimed to quantify simultaneous, linear association between both child and horse heart rates at each observation (see Fig. 3).

Most correlations were significant with R > 0.5, suggesting that in a majority of cases, increases in a child’s heart rate were associated with corresponding increases in the horse’s hear rate, or vice-versa. Notably, the highest correlation approached 0.95 (e.g. Observation 3), whereas one pair (Observation 15) demonstrated a slightly negative correlation, around − 0.05. Overall, correlations for individual pairs spanned a broad range but tended toward moderate to strong positive values. A bootstrapping procedure25, based on 1000 resamples with replacement, indicated that the average correlation across all pairs was approximately 0.535 (Fig. 4), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.5275, 0.5425]; this relatively narrow interval suggests that on average, child-horse heart rates correlation exhibit a robust linear association.

The cross-correlation analysis demonstrated significant peaks at lag zero and nearby lags for many pairs. In some instances, the peak cross-correlation occurred at a positive lag, suggesting that the child’s heart rate led the horse’s heart rate, while in others, a negative lag indicated the opposite (see Table 1).

Most cross-correlation plots remained stable between 0.6 and 0.8 across the entire lag range, with only slight declines over the 0–5 s interval. On average, the maximum cross-correlation coefficient across pairs was 0.939, with 20 pairs (80%) showing significant cross-correlations at lag 0 (above 0.5), while in a few instances, cross-correlation peaked sharply around lag 5 (see Table 1). These findings suggest the presence of both synchronous and time-lagged associations, hinting at a complex interplay between the physiological states of children and horses during shared activities. Although cross-correlation does not imply causation, the strong values observed suggest a consistent co-variation pattern between the two time series.

Granger causality testing with block permutation

Many child-horse pairs exhibited significant Granger causality in at least one direction, indicating that each partner’s past heart rate carries information about the other’s future state (Fig. 5). A subset of pairs showed p-values below 0.05 for child-to-horse predictive relationships, while others demonstrated horse-to-child predictability. In total, 17 pairs showed significant Granger causality from child to horse (n = 7), from horse to child (n = 6), or in both direction (n = 4), with p < 0.05. The overall percentage of pairs demonstrating significant predictive relationships was 80% for neurotypical and 60% for children with ADHD, respectively (see Table 2).

Although referred to as “causality” in name, the test here is better interpreted as reflecting predictive links rather than absolute proof of causal mechanisms. Nonetheless, the presence of significant Granger causality in a considerable number of pairs suggests that the children’s and horses’ heart rates are interdependent over time, reinforcing the notion of a coordinated or responsive physiological connection within each dyad.

Permutation testing across pairs

The proportion of significant pairs – 68% – was markedly higher than the range that prevailed in the null distribution’s center (around 30%), obtained from 250 shuffled pairings. Consequently, the p-value was near zero, indicating that it would be highly improbable for the original data’s results to occur by mere random assignment of children to horses. This second permutation step shows that the relationships captured by Granger causality tests are not simply artifacts of pairing arbitrary child and horse data (see Fig. 5). This finding suggests that the predictive relationships observed between the children’s and horses’ heart rates are unlikely to be due to random chance and may reflect meaningful associations specific to the original pairings.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore heart rate synchronization between horses and riders in two groups of children aged 6–12: novice riders diagnosed with ADHD and experienced neurotypical riders. Combining the analysis methods described above provides a nuanced picture of child-horse heart rate dynamics. Correlation analyses highlighted strong associations, while cross-correlation analyses confirmed synchronous patterns for most pairs. Granger causality testing uncovered predictive relationships in a substantial fraction of the dataset, signifying that each partner’s historical heart rate can forecast the other’s subsequent rate. The final permutation test across pairs affirmed that the overall proportion of significant pairs is unlikely to be explained by random chance.

Our findings align with scarce previous research indicating that horse-human interactions can lead to physiological synchronization, as evidenced by changes in heart rate and HRV7,8. These studies have primarily focused on unmounted activities, such as grooming and handling, which were found to positively impact participants’ heart rates and HRV, suggesting a beneficial interaction with the equine partner8. Another study has found heart rate synchronization between horses and older adults1. However, our study is among the first to explore mounted synchronization among children using multiple horses, adding new dimensions to the existing body of research.

The study has found high synchronization between horse and rider beyond diagnosis and experience among varied horses. Of interest, is that the horse and rider mutually affect each other, indicating harmony and synchronization between the two. More specifically, in both groups, our results indicate in some dyads horse-child effect as well as child-horse effect in others. In the neurotypical group, 6 dyads affected each other both ways, whereas in the ADHD group only two dyads had a two-way effect. Due to the differences between the groups in terms of riding experience, diagnosis and familiarity with the horse it is hard to draw conclusions regarding the differences in synchronization frequency.

It is suggested that the synchronization observed between horse and rider, is crucial for a successful riding and for bonding with the horse. While riding a horse, the rider is submerged in a total immerse experience, as constant immediate feedback from the horse’s movement and behavior is received from the horse to the rider and vice versa, thus enabling physical and mental self-regulation26. A successful riding requires the control of one’s body and the ability to regulate its strength in response to the horse’s movements and the demands of different riding gaits27. Along with regulating himself, the rider must trust his horse and learn to control it, while taking care of it and fulfilling all his needs28. Therefore, riding the horse might serve as a form of biofeedback, increasing the rider’s awareness of bodily signals and promoting interoception. This process aligns with one of the therapeutic goals while working with children with ADHD who often struggle with regulation and self-control19. The rhythmic interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, facilitated by horse-human interactions, may contribute to decreased stress and anxiety, improved mental and physical performance, and a more synchronized connection between the heart and brain1.

Importantly, although higher synchronization levels were expected among the neurotypical group, it is remarkable that children with ADHD, despite being novice riders, paired with random horses, and facing regulation challenges, also reached synchronization levels significantly above random chance by the fourth and sixth session. This finding emphasizes the horse’s unique role as a therapeutic partner: horses naturally facilitate physiological and emotional regulation, even in populations typically characterized by difficulties in self-regulation and interpersonal attunement. The ability of horses to engage so quickly and deeply with novice riders highlights their therapeutic value and underscores their potential in interventions aimed at enhancing emotional and physiological regulation.

Furthermore, both study groups have demonstrated high mutual synchronization levels between equines and riders, despite one group having ADHD and being new to riding, which may indicate on the horse ability to facilitate regulation. This process might also involve emotional transference where emotions and feelings are unconsciously redirected or transferred to the horse, thus influencing the synchronization. The synchronization presented in the two distinctive groups may indicate the mutual under mechanism of horse-human relationship that may be generalized to varied riders.

It is important to note that although heart rate synchronization may reflect physiological attunement, it does not necessarily indicate a positive experience for horses. Studies have shown that therapeutic riding can be associated with stress-related behaviors and elevated cortisol in horses29,30. These findings highlight the need for caution when interpreting HR data and suggest that future research should include behavioral and additional physiological measures to assess equine well-being.

Clinical significance

Our study may offer a preliminary perspective on the interaction between horse and rider by examining heart rate synchronization as an index of physiological co-regulation. Importantly, the findings suggest that monitoring heart rate synchronization could serve as one component in tailoring horse-rider pairings. This perspective may contribute to the growing field of human-animal interaction by offering physiological metrics that support individualized approaches to EAS. For children with ADHD, who often experience challenges in self-regulation, behavioral organization, and emotional control, structured co-regulation with the horse has a positive effect with the horse that may support the development of regulatory capacities through embodied interaction. However, any interpretation of these effects in terms of emotional or mental health benefits should be made cautiously and require future studies that integrate psychological and functional measures. While both increases and decreases in heart rate were observed, we suggest that these shifts may reflect adaptive responses such as arousal, engagement, or relaxation depending on the therapeutic context. Future studies may benefit from including HRV measures, which are more sensitive to parasympathetic regulation and may better capture emotional or stress-related changes.

Importantly, the findings suggest that monitoring heart rate synchronization could offer a novel, objective method for tailoring horse-rider pairings, optimizing therapeutic outcomes based on the quality of physiological attunement between partners. Nevertheless, synchronization should be considered alongside other critical factors, such as the horse’s temperament, body build, and the physical and psychological compatibility between horse and rider.

Study limitation and future research

Although the results suggest potential physiological linkages, the limitations of the study warrant careful interpretation. The analyses were observational in nature, and references to “predictive relationships” must be understood within the constraints of Granger causality, which does not establish true causation. While heart rate synchronization is a valuable measure of physiological attunement, it is influenced by a myriad of factors including physical activity levels, emotional states, and external environmental conditions. Although efforts were made to control these variables, some confounding factors may have impacted the results. For instance, without standardized control over the timing and duration of each gait (walk, trot, canter), variability in exertion may have contributed to the observed heart rate changes. Since both human and equine heart rate naturally increase with physical activity, it is possible that parts of the synchronization reflect mutual physiological responses to movement, rather than emotional attunement. Future studies should consider implementing a standardized riding protocol to better isolate the contribution of emotional versus physical factors to physiological synchronization. Moreover, adding a control group as HR measurements in horses during similar movement pattern without a child on their back may shed light on heart rate synchronization mechanism.

In addition, a key limitation of this study design is the confounding of two variables -the two groups differed along two dimensions, riding experience and mental health status, which prevents isolating the effect of either variable on synchronization. Consequently, we did not perform direct statistical comparisons between the groups, and any observed differences should be interpreted as exploratory and descriptive rather than inferential. Additionally, the small sample size of 25 child-horse with a focus on a specific age group and gender, constrains the generalizability of the findings and may reduce statistical power. Future research should aim to include larger, more diverse populations to validate and extend these findings Finally, this was a preliminary study that aimed to assess whether heart rate synchronization could be observed at all between horses and children. While promising, our findings should be interpreted with caution and viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. If future research seeks to link synchronization to therapeutic outcomes, it will be essential to monitor broader EAS effects such as changes in emotional regulation, mental health, or daily functioning, ideally comparing participants who do and do not exhibit physiological attunement.

.

Conclusion

This study highlights the potential of EAS in promoting physiological and, possibly, emotional regulation through horse-human heart rhythm synchronization. The mutual heart rate synchronization observed between horses and both neurotypical children and those with ADHD suggests that EAS underlie the therapeutic effect of these interventions. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms at play and to explore the broader applications of these findings in therapeutic settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baldwin, A., Walters, L., … B. R.-P. and A. & 2023, undefined. Effects of Equine Interaction on Mutual Autonomic Nervous System Responses and Interoception in a Learning Program for Older Adults. docs.lib.purdue.eduAL Baldwin, L Walters, BK Rector, AC AldenPeople and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 2023•docs.lib.purdue.edu 6, 2023 (2023).

Taelman, J., Vandeput, S., Spaepen, A. & Van Huffel, S. Influence of mental stress on heart rate and heart rate variability. IFMBE Proc. 22, 1366–1369 (2008).

von Borell, E. et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals — A review. Physiol. Behav. 92, 293–316 (2007).

Kutscheidt, K. et al. Interoceptive awareness in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders. 11, 395–401 (2019).

Critchley, H. D. & Garfinkel, S. N. Interoception and emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology vol. 17 7–14 Preprint at (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.020

Viry, S. et al. Patterns of Horse-Rider coordination during endurance race: A dynamical system approach. PLoS One. 8, e71804 (2013).

Hockenhull, J., Young, T., Redgate, S. & Anthrozoös, L. B. & undefined. Exploring synchronicity in the heart rates of familiar and unfamiliar pairs of horses and humans undertaking an in-hand task. Taylor & Francis (2015). (2015).

Guidi, A., Lanata, A., Baragli, P., Valenza, G. & Scilingo, E. P. A wearable system for the evaluation of the Human-Horse interaction: A preliminary study. (2016). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics5040063

von Lewinski, M. et al. Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: different responses to training and performance. Vet. J. 197, 229–232 (2013).

Wood, W. et al. Optimal terminology for services in the united States that incorporate horses to benefit people: A consensus document. Liebertpub com. 27, 88–95 (2021).

Helmer, A., Wechsler, T. & Gilboa, Y. Equine-Assisted services for children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 27, 477–488 (2021).

Arnon, S. et al. Equine-Assisted therapy for veterans with PTSD: manual development and preliminary findings. Mil Med. 185, E557–E564 (2020).

Fisher, P. W. et al. Equine-Assisted therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among military veterans: an open trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 82, 36449 (2021).

Earles, J. L., Vernon, L. L. & Yetz, J. P. Equine-Assisted therapy for anxiety and posttraumatic stress symptoms. J. Trauma. Stress. 28, 149–152 (2015).

Arnon, S. et al. Equine-assisted therapy for veterans with PTSD: Manual development and preliminary findings. academic.oup.comS Arnon, PW Fisher, A Pickover, A Lowell, JB Turner, A Hilburn, J Jacob-McVey, BE MalajianMilitary medicine, 2020•academic.oup.com 185, (2018). (2020).

Fine, A. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions (Academic, 2019).

American Psychiatric Asociation. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2000 text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 216. (2013). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=American+Psychiatric+Association+.+%282013%29.+Diagnostic+and+statistical+manual+of+mental+disorder+%285th+ed.%29.+Washington%2C+DC%3A+Author.&btnG= (2013).

Wolraich, M., Hagan, J., Allan, C. & Chan, E. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. publications.aap.org (2019).

Cibrian, F. L., Lakes, K. D., Schuck, S. E. B. & Hayes, G. R. The potential for emerging technologies to support self-regulation in children with ADHD: A literature review. Int J. Child. Comput. Interact 31, (2022).

Wehmeier, P., Schacht, A. & health, R. B. J. of A. & undefined. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. Elsevier (2010). (2010).

Mahler, K. Interoception: the Eighth Sensory System. Shawnee Mission (KS, 2015).

Prišenk, J. et al. The Art equipment for measuring the horse’s heart rate. Researchgate Net. 41, 180–186 (2010).

Shojaie, A., Its, E. F.-A. R. of S. and & 2022, undefined. Granger causality: A review and recent advances. annualreviews.org 9, 289–319 (2022).

Arboretti, R., Barzizza, E., … N. B.-J. of M. & 2025, undefined. A review of multivariate permutation tests: Findings and trends. ElsevierR Arboretti, E Barzizza, N Biasetton, M DisegnaJournal of Multivariate Analysis,2025•Elsevier.

Horowitz, J. L. Bootstrap methods in econometrics. Annu. Rev. Econom. 11, 193–224 (2019).

So, W. Y., Lee, S. Y., Park, Y. & Seo, D. Il. Effects of 4 weeks of horseback riding on anxiety, depression, and self esteem in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Mens Health. 13, e1–e7 (2017).

Martin, R. A., Graham, F. P., Taylor, W. J. & Levack, W. M. M. Mechanisms of change for children participating in therapeutic horse riding: A grounded theory. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 38, 510–526 (2018).

Bachi, K., Terkel, J. & psychology, M. T. C. child & undefined. Equine-facilitated psychotherapy for at-risk adolescents: The influence on self-image, self-control and trust. journals.sagepub.com 17, 298–312 (2012). (2012).

Hovey, M. R., Davis, A., Chen, S., Godwin, P. & Porr, C. A. S. Evaluating stress in riding horses: part One—Behavior assessment and serum cortisol. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 96, 103297 (2021).

Kaiser, L., Heleski, C. R., Siegford, J. & Smith, K. A. Stress-related behaviors among horses used in a therapeutic riding program. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 228, 39–45 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their invaluable contribution to this study. We are also deeply grateful to the horses, whose presence and partnership made this research possible.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H. and O.B. wrote the main manuscript text A.H did the analyses and prepared tables and graphs.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Helmer, A., Hacohen, A. & Bart, O. Child horse harmony in motion: a preliminary study to explore heart rate synchronization in equine assisted therapy for neurotypical and ADHD children. Sci Rep 15, 45312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29330-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29330-6