Abstract

HER2-low breast cancer (BC) representing about 40–55% of all BC has emerged as a targetable entity. However, little is known about the link between germline BRCA1/2 mutations (gBRCA1/2) and HER2-low status in BC, especially in Ukrainian population. This study aims to elaborate on the rates of HER2-low status among patients with sporadic and BRCA1/2-associated hereditary BC in the Ukrainian population and investigate the relationship between gBRCA1/2 and HER2 status. This was a retrospective multicenter cross-sectional study on 1412 cases of BC. HER2 status was assessed according to ASCO-CAP Guidelines. All patients underwent germline NGS testing to detect SNV and indel variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Overall, gBRCA1/2 genetic variants were found in 212 (15.0%) patients with BC. gBRCA1 variants were associated mostly with TNBC molecular subtype, while gBRCA2 mutations were linked to Luminal-like BC. The majority (343 of 436; 78.7%) of HER2-low BC was associated with luminal-like BC (P < 0.001). We also found significant relationships between gBRCA1/2 and HER2 status (P = 0.006). There were 837 HER2-zero (59.3%), 436 HER2-low (30.9%) and 139 HER2-positive (9.8%) BC. More than 70% of patients with gBRCA1 were HER2-negative. Alternatively, gBRCA2 cases possessed a higher rate of HER-low BC status (37.5%) as compared to WT (31.2%) and gBRCA1-associated BC (25.7%). In conclusion, gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 variants differed in their association with breast carcinoma molecular subtype and HER2-low status. gBRCA1 variants were linked to the prevalence of TNBC type and HER2 zero status. In contrast, gBRCA2 cases had a higher rate of HR + and HER-low breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer death in women1,2. The intimidating trend of continuous rise in BC incidence has been a driving force stimulating biomarker discovery and exploration of molecular landscape of BC3,4. Molecular classification of BC, evaluating the expression of estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PgR) receptors, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and Ki-67 was recognized as a robust approach for analysis of tumor biology, guiding patient prognosis and approach to treatment3. According to the 2011 St. Gallen Consensus Conference, depending on the status of these biomarkers, luminal A, luminal B, HER2-positive, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) entities were distinguished5. Among them HER2-positive BC was traditionally defined as the one with increased HER2 protein expression level (reaching IHC score 3 + or 2 + demonstrating amplification of ERBB2 gene, coding HER2, confirmed via in situ hybridization)6. HER2-positive BC is associated with highly aggressive tumor behavior and poor prognosis, as well as sensitivity to anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies, such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab7. Anti-HER2 agents were shown to improve the prognosis in patients with HER2-positive primary and metastatic BC8.

Notably, only around 15–20% of BC are HER2-positive which presents a limited application of targeted anti-HER2 therapeutic agents9,10. This paradigm shifted when researchers uncovered the specific biological features of BC tumors with low HER2 expression11. As a result, American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) guidelines and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) expert consensus statements established a new subtype of HER2-low BC, defined as those with a low but still detectable level of HER2 expression (IHC score 1 + or 2 + without ERBB2 gene amplification)12. Based on this definition, HER2-negative breast cancer was further divided into HER2-low and HER2-zero (tumors with IHC score 0) BC. HER2-low BC demonstrated a good response to antibody-drug conjugates (ADC)13. Thereafter, the statement of HER2-negative tumors being insensitive to anti-HER2 therapy was reconsidered in August 2022, when trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu, T-DXd) became the first therapy approved to treat patients with metastatic HER2-low breast cancer14.

Approximately 40–55% of all BC cases belong to HER2-low subtype15,16. Recent studies showed that most HER2-low BC exhibit hormone-receptor (HR) expression13. According to four prospective neoadjuvant clinical trials, more than 60% patients with HER2-low tumors were HR positive16. At the same time only 36.7% of HR positive tumors were HER2-zero (P < 0.001)16. Similarly, HR-positive BC demonstrated around two times higher prevalence of HER2-low tumors compared to TNBC17. Similarly, Tarantino et al. in a large cohort of BC patients, showed the prevalence of HR expression among HER2-low compared to HER2-negative BC tumors, underscoring that high ER score is associated with elevated HER2 expression18.

Beyond molecular classification, genetic predisposition also impacts prognosis, surveillance, and management of BC patients. This involves hereditary syndromes that increase the risk of BC and influence treatment approaches. Around 10% of all BC are caused by germline mutations, mostly attributed to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome19. The most renowned and clinically impactful here are germline mutations in BReast CAncer gene 1 and 2 (gBRCA1/2). Individuals with gBRCA1/2 variants face an increased absolute risk of developing BC that exceeded 60%. The incidence of gBRCA1/2 varies between populations and among different clinical groups. For example, patients with TNBC are reported to have gBRCA1/2 mutation in up to 15.4% cases20. However, little is known about the prevalence of HER2-low BC in patients harboring pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants (PV and LPV) in BRCA1/2. Recent study shed light on this issue demonstrating that HER2-low status was found in 32.3% young patients with early-stage Luminal-like BC harboring gBRCA1/2 PVs21. Importantly, this international multicenter study enrolled women under 40 from different countries and ethnic groups. While epidemiology of HBOC is well established in most high-income countries, the incidence and spectrum of gBRCA1/2 variants in low- and middle-income countries including Ukraine is lesser known. Within the published studies, there is a great discrepancy in patient groups, methods and scopes of testing performed, as well as in sampling approaches, limiting the groups to specific territories of Ukraine. Most studies employ a PCR-based method detecting founder BRCA1/2 mutations which are most common worldwide and a single next generation sequencing (NGS) based study focused on specifically western Ukraine22,23. A common limitation to our understanding of Ukrainian BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, however, lies within the scopes of these studies, reaching up to 200 patients each. Moreover, there is no data about the links between HER2 status and gBRCA1/2 status in Ukrainian population.

This study aims to elaborate on the rates of HER2-low status among patients with sporadic and hereditary BC in the Ukrainian population and investigate the relationship between gBRCA1/2 and HER2 status.

Results

General characteristics of BC patients

The median age of patients at the time of diagnosis was 46 (IQR 41–54). Overall, gBRCA1/2 genetic variants were found in 212 (15.0%) out of 1412 enrolled patients with BC. The rate of gBRCA1 variants was more than twice as high (10.5%) compared to gBRCA2 (64; 4.5%). In this study, 843 patients (59.7%) had Luminal-like BC, 430 cases (30.45%) possessed TNBC and a small portion of cases (139 of 1412, 9.84%) had HER2-enriched invasive BC. Among the study group, 117 patients (8.3%) had grade 1 (G1) tumors, 731 (51.8%) had G2 tumors, and 564 (39.9%) were diagnosed with G3 tumors (Table 1). Most patients carrying gBRCA1/2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were diagnosed with BC of G3 (123 of 212 patients, 58.02%; P < 0.001). Less frequently, patients with gBRCA1/2 were diagnosed with G2 BC (79/212; 37.3%) and G1 BC (10/212, 4.72%; Fig. 1A).

The relationship between the presence of gBRCA1/2 variants and tumor biology. A — demonstrates the link between presence gBRCA1/2 genetic variants and poor differentiation of cancer cells. B — shows differences in Ki-67 expression in nuclei of tumor cells, highlighting the elevated cell proliferation in BC with gBRCA1 variants.

The presence of gBRCA1 variants was also associated with the highest rate of cell proliferation in BC samples assessed through Ki-67 expression assessment by IHC (50.0; IQR 32.5–80.0%; P < 0.001) compared to tumors with gBRCA2 mutation (35.0; IQR 21.3–60.0) and wild type (WT) tumors (30.0; 20.0–50.0) (Fig. 1B).

Spectrum of gBRCA1/2 variants in Ukrainian patients with BC

According to our data, we have identified 8 major gBRCA1/2 variants (7 in BRCA1 and 1 in BRCA2) that were found in 53.3% of patients with BC harboring gBRCA1/2. BRCA1 c.5266dup (p.Gln1756fs) genetic variant was the most common pathogenic mutation among Ukrainian patients with BC and accounted for 32.54% of patients harboring gBRCA1/2 (69 of 212 patients). Genetic variant c.181T > G (p.Cys61Gly) of BRCA1 gene was the second most frequent pathogenic mutation found in 8.49% of cases (18 of 212 patients). Variants BRCA1 c.4035del (p.Glu1346fs) and BRCA2 c.475 + 1G > T were detected in 2.35% each (5 patients out of 212). The next most frequent variants were identified in 1.88% cases each (4 patients out of 212) and included 4 pathogenic mutations of BRCA1 gene, namely c.1510del (p.Arg504fs), c.1961del (p.Lys654fs), c.68_69del (p.Glu23fs) and c.5177_5180del (p.Arg1726fs). The rest of BRCA1/2 variants were present in smaller subsets of patients. Four genetic variants (3 frameshift and 1 stop gain variant) were identified in 3 patients each: c.5030_5033del (p.Thr1677fs) in BRCA1 and c.5238dup (p.Asn1747Ter), c.658_659del (p.Val220fs), c.9097dup (p.Thr3033fs) in BRCA2.

Fourteen BRCA1/2 variants (7 in BRCA1 and 7 in BRCA2) were found in two patients each. Among them 9 were frameshift variants, 3 – stop gain, 1 – splice site and 1 – missense. Most of the less common gBRCA1/2 variants were well annotated and presented in public databases with clear evidence of clinical significance. There were also singular variants found in patients: 23 in BRCA1 and 36 in BRCA2, of which 30 are frameshift variants, 16 – stop gain, 10 – missense, 2 – splice site, and 1 – inframe deletion (Fig. 2).

Among these findings, however, we identified rare single nucleotide variants (SNV) and insertions-deletions (indels) that had not yet been described previously in literature or public databases. These were found in singular patients and classified as Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic using the Association for Clinical Genomics Science (ACGS) 2020 guidelines24. They included BRCA2 c.9795 C > A (p.Cys3265Ter), BRCA2 c.5564del (p.Ser1855fs), BRCA2 c.3410dup (p.Leu1137fs), BRCA1 c.1647dup (p.Asn550Ter), BRCA1 c.2099_2108del (p.Leu700fs), BRCA2 c.6593del (p.Thr2199fs), BRCA1 c.1505T > A (p.Leu502Ter), BRCA2 c.2228dup (p.His743fs), BRCA2 c.4240del (p.Thr1414fs), BRCA2 c.7538_7547del (p.Lys2514fs), BRCA1 c.4190_4191insGGATACCATGCAACATAACCTGA (p.Ile1405fs). Further studies are necessary to elaborate on the functional effects of these discovered variants.

Correlation between age of onset and gBRCA1/2 mutation incidence in women with BC

The incidence of gBRCA1/2 mutation was high in young women diagnosed with BC and decreases progressively with age. Among the observed patients there were 322 diagnosed with BC under 40 years old, with 61 cases carrying gBRCA1/2 (18.9%). Naturally the incidence of gBRCA1/2 was lower among women over 40 (13.9%; P = 0.0247). The frequency of gBRCA1/2 variants among women under 50 (904; 64%) reached 17.3% that was significantly higher than in women over 50 at the time of diagnosis (11.0%; P = 0.0017). Comparing other age categories, 195 (13.8%) patients with BC were older than 60 at the time of diagnosis, and only 105 women (7.4%) in the observed cohort were over 65 years old (Table 1). The incidences of gBRCA1/2 variants among cases under 60 and 65 were 16.4% and 15.9% (P < 0.001) respectively. Thus, early onset of BC suggests a higher probability that the woman may harbor gBRCA1/2 variants25. However, we did not find the association between age and HER2-status.

Importantly, early-onset breast cancer was associated with specific germline variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Among the 61 cases with gBRCA1/2 variants found in patients under 40, c.5266dup (p.Gln1756fs) was the most prevalent (17 of 61 patients; 27.9%), however this number represented just 24.6% of all patients with this variant. Next, c.181T > G (p.Cys61Gly) was detected in 7 of 61 patients (11.5%), corresponding to 38.9% of this all the carriers of this variant. The rest (more than half) of young patients had rare variants. Among them c.3756_3759del (p.Ser1253fs) and c.5251 C > T (p.Arg1751Ter) of BRCA1 and c.468dup (p.Lys157Ter) of BRCA2 were found in 2 cases each being exclusively related to age under 40. Many other variants of BRCA1 and BRCA2 were found in young age women with BC (Table 2).

The similar analysis of gBRCA1/2 variants incidence among women under and over 50 years old demonstrated that 72.5% and 83.3% of c.5266dup and c.181T > G BRCA1 variants respectively were associated with BC development in age before 50. Similarly, the association with early onset BC was found for c.1510del, c.1961del, c.5177_5180del, c.68_69del, and c.5030_5033del, c.3627dup, c.3756_3759del, c.5251 C > T variants in BRCA1 and c.658_659del, c.1813dup, c.3975_3978dup, c.468dup, c.5152 + 1G > T, c.6998dup, c.7251_7252del, c.7758G > A variants in BRCA2. In contrast, there were some variants detected in women with BC onset after the age of 50 (Suppl. Table 1).

The relationship between gBRCA1/2 and HR status of BC

The presence of gBRCA1/2 variants was closely related to the BC molecular subtype and HR expression (P < 0.001; Suppl. Table 2). gBRCA1 variants were associated mostly with TNBC molecular subtype, while gBRCA2 variants were linked to Luminal-like BC subtypes (Fig. 3, Suppl. Table 3). The rate of gBRCA1/2m in TNBC was high, reaching 26.3%. Most of these patients (98; 22.8%) had gBRCA1 and a smaller fraction harbored gBRCA2 variant (15; 3.5%). The rate of gBRCA1/2 variants was lower among women with Luminal-like BC subtypes (90 of 843 patients had gBRCA1/2 variants, 10.7%), while HER2-enriched subtype was associated with the lowest rate of gBRCA1/2 mutation (6.5%). We found specific BRCA1/2 genetic variants associated with different molecular subtypes (see Suppl. Table 2).

gBRCA1 variants are associated with TNBC, while gBRCA2 variants are linked to Luminal-like breast cancer. A — demonstrates the distribution of various molecular subtypes in patients with no gBRCA1/2 (WT). B — demonstrates the prevalence of TNBC in patients with gBRCA1. C - shows prevalence of Luminal-like BC in patients with gBRCA2 variants.

Naturally, these distinctions between genetic findings and tumor biology were closely related to the different association of gBRCA1/2 variants on HR status. Among patients with gBRCA2m allele 75% (48 of 64) were associated with HR-positive status, while women with gBRCA1 variants demonstrated only 31.1% of HR positive BC (Fig. 4).

There was also an association between HR and HER2 status in BC (P < 0.001). HR-positive status was found in 920 of 1412 BC cases (65.2%). Among them 77 (8.4%) tumors were HER2-positive, 343 (37.3%) – HER2-low and 500 (54.3%) – HER2-zero. The rates of HER2 expression differed in HR-negative BC (n = 492 of 1412; 34.8%). Although the rate of HER2-positive BC was found in 12.5% (62 of 492 HR-negative BC), only 93 cases of this subgroup (18.9%) were HER2-low, and the rest 337 (68.5%) demonstrated HER2-zero status.

Thus, gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 variants differ in their effects on BC biology and molecular subtypes. While gBRCA1 variants were associated with HR expression loss and TNBC subtype, gBRCA2 variants were linked to HR-positive status and Luminal-like BC subtype.

gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 genetic variants differently related to HER2-status

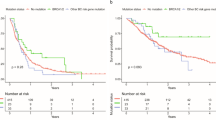

Overall, there were 837 HER2-negative (59.3%), 436 HER2-low (30.9%) and 139 HER2-positive (9.8%) BC among the study sample. The HER2-low status was twice as high in Luminal-like BC as compared to TNBC (P < 0.001). HER2-low status was found in 343 (40.7%) out of 843 Luminal-like BC while only 93 (21.6%) of 430 TNBC demonstrated the same level of HER2 expression at IHC (Fig. 5). Thus, the Luminal-like BC had proportionately more HER2-low expression, while TNBC were mainly HER2-zero.

When comparing BRCA1/2 variants-associated tumors with WT BC it seemed that carrying gBRCA1/2 was linked to HER2 negativity and lower rate of HER-low and HER2+ status (P = 0.006). There were 141 (66.5%) HER2 negative cases among 212 patients with gBRCA1/2, 62 (29.2%) demonstrated HER2-low status and only 9 (4.2%) were HER2-positive (P < 0.001). However, gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 differently impacted tumor biology. HER2-zero status was mostly linked to gBRCA1 variants (P = 0.006; Table 3), as more than 70% of gBRCA1 cases were HER2-zero. In patients with gBRCA2 and WT BC the rate of HER-zero status was lower comprising 56.2% and 58% respectively. Among WT tumors the proportion of HER2-positive status was the highest reaching 10.8%, while in gBRCA2m BC it accounted for 6.2% and in gBRCA1m BC was the lowest (3.6%). Notably, HER-low status rate was detected in 37.5% of patients with gBRCA2 carriers, that was higher than in WT-breast carcinomas (31.2%) and patients with gBRCA1 variants (25.7%). Thus, gBRCA1 cases demonstrated the highest rate of HER2-negative BC (70.9%), while gBRCA2m BC possessed HER2-low status in more than one third of cases (Suppl. Table 4).

At the next step we assessed the relationship between various HER2 status and different BRCA1/2 variants (Table 3). HER2-positive BC was related to the limited number of variants. The following variants demonstrated the high incidence of association with HER2-positive status: c.181T > G and c.4035del in BRCA1 and 4 different variants in BRCA2 (c.658_659del, c.517G > T, c.7975 A > G, and c.9253dup). Only 2 of 69 (2.89%) patients with common c.5266dup variant were linked to HER2-positive BC. Notably, several gBRCA2 variants demonstrated links to HER2-low status: c.475 + 1G > T (3/5, 60%), c.5238dup (2/3; 66.7%), c.9097dup (2/3; 66.7%). At the same time there were several gBRCA1 variants that were related to HER2-low expression (Table 3). Notably, the most common variants of gBRCA1 demonstrated a lower incidence of HER-2-low status: 15 of 69 c.5266dup cases (21.7%) and 2 of 18 patients with c.181T > G (22.2%) were HER2-low.

To sum up, the most common variants of gBRCA1 were associated with HER2-zero status of BC, while gBRCA2 demonstrated a higher rate of HER2 up-regulation defining HER2-low status. Several variants of gBRCA1/2 were linked to low or even high HER2 expression.

Discussion

This large-scale Ukrainian study defined the rate and the spectrum of gBRCA1/2 variants in large sample of Ukrainian population, although there were the previous studies describing BRCA1/2 variants in Ukraine based on limited cohorts up to 123 Ukrainian patients with breast and ovarian cancers22. Moreover, some other studies relied on PCR testing focusing on the most common variants23. In this research we provided the results of NGS testing in 1412 women with histologically confirmed invasive BC and revealed that 212 of them (15%) had gBRCA1/2 variants. This relatively high rate of gBRCA1/2 could be related to medical indications for genetic testing and prevalence of young age patients in the study population with the average age 46 (41–54), though in previous study the rate of patients with gBRCA1/2 was even higher (16.3%)22.

The most common variants of BRCA1 were c.5266dup (p.Gln1756fs) and c.181T > G (p.Cys61Gly). In Ukrainian cohort they accounted for 32.54% and 8.5% among gBRCA1/2 cases. These data align with other reports demonstrating that c.5266dup (p.Gln1756fs) and c.181T > G (p.Cys61Gly) BRCA1 variants are common European founder mutations and are also prevalent in Poland and in the Czech Republic22,26. Using NGS technology we were able to define the whole spectrum of gBRCA1/2 variants most of which were previously annotated, including c.4035del (p.Glu1346fs), c.5030_5033del (p.Thr1677fs), c.1510del (p.Arg504fs), c.1961del (p.Lys654fs), c.68_69del (p.Glu23fs) and c.5177_5180del (p.Arg1726fs) variants in BRCA1. The rate of gBRCA2 variants in Ukrainian patients with BC was lower as compared to gBRCA1 comprising 30.1% of all BRCA1/2-associated BC. The most common gBRCA2 variant was c.475 + 1G > T. Other gBRCA2 variants included c.5238dup (p.Asn1747Ter), c.658_659del (p.Val220fs), c.6998dup (p.Pro2334fs), c.7251_7252del (p.His2417fs), c.7758G > A (p.Trp2586Ter), c.9097dup (p.Thr3033fs) and c.9253dup (p.Thr3085fs).

Most of the rarer BRCA1/2 variants were well-annotated and listed in public databases with clear evidence of clinical significance. There were also singular variants found in patients: 23 in BRCA1 and 36 in BRCA2, of which 30 are frameshift variants, 16 – stop gain, 10 – missense, 2 – splice site, and 1 – inframe deletion (Suppl. Table 2). Among our findings, however, we identified rare SNV and indels that had not yet been described in literature or public databases. These were found in singular patients and classified as Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic using ACGS 2020 guidelines24. It is worth noting, in this study included the data on BRCA1/2 testing without PALB2 and other Homologous recombination repair (HRR) genes recommended by European Molecular Genetics Quality Network the (EMQN) best practices for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC)27.

Carrying gBRCA1/2m was associated with the younger age of BC development. We also demonstrated that in Ukrainian population more than half cases of early onset of BC are linked to rare variants of gBRCA1 and gBRCA2. Our findings highlight the need in NGS testing covering the coding sequence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 for identifying rare variants predisposing to early BC. This finding highlights the importance of BRCA1/2 sequencing instead of common variants testing, for detecting a variety of germline variants, predisposing to early onset of BC. Besides, the incidence of gBRCA1/2 variants differed significantly between women under and over 60–65 years old. Considering the impact of gBRCA1/2 variants on breast cancer patients’ surveillance, surgery, and treatment, it is essential to broaden the indications for BRCA1/2 testing in patients under 65 years, as recommended by ASCO28. ASCO guidelines recommend gBRCA1/2 testing to all newly diagnosed people with BC ≤ 65 years and selected patients over 65 who have personal or family history ancestry or eligible for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor therapy28. Besides BRCA1/2 testing should be considered in case of the second primary cancer or recurrent BC if patients are candidates for PARPi therapy regardless of family history28.

Although HER2-positive BC is uncommonly associated with BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants, we found the association between gBRCA2 and HER2-low status and HR expression maintenance. Recent study also demonstrated the links between HER2-low BC and defects in homologous recombination repair genes (HRR). HER2-low BC were found to harbor frequent mutations in HRR genes that define a higher homology recombination deficiency (HRD) score and the increased level of genomic instability. These alterations can affect patient’s prognosis as elevated HRD score in HER2-low tumors correlated with poorer progression-free survival, especially in hormone receptor–positive cases29. On the other hand, the association with DNA repair defects in HER2-low tumors opens up opportunities for innovative therapeutic approaches30,31. Tumors with BRCA1/2 mutations are sensitive to PARP inhibitors and may exhibit an altered immune microenvironment, which might enhance responsiveness to immunotherapy32. These relationships highlight the possibility of exploiting synthetic lethality strategies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in a subset of patients with HER2-low BC in patients with gBRCA1/2.

Our findings revealed that gBRCA2-associated breast cancers were more frequently HR-positive than those associated with gBRCA1 mutations, which align with results from other investigations21,33. For instance, large multicenter study that included 3547 women aged ≤ 40 years with newly diagnosed early-stage HER2-zero and HER2-low BC with germline BRCA1/2 PVs demonstrated that HER2-low BC was mostly associated with HR-positive and significantly less frequently with TNBC21. Other studies also reported that high proportion of HER2-low tumors demonstrated Luminal-like type gene expression with maintained ER and related pathways expression32. Some reports noticed differences in age at diagnosis and tumor grade, with HER2-low tumors having less aggressive features compared to HER2-zero cases, though results can vary by population34,35. Assessment of genetic profile of HER2-low tumors demonstrated also a higher rate of genetic alteration in PI3K-Akt signaling pathway as compared to HER2-positive and HER2-zero BC30. In contrast HER2-zero BC showed more alterations in checkpoint factors, Fanconi anemia genes and p53 signaling, as well as cell cycle pathway compared to HER2-low breast tumors.

Important, HR positive BC with gBRCA1/2 were shown to have more aggressive tumor phenotypes as compared to sporadic cancer. Adjuvant hormone therapy (tamoxifen) is indicated for patients HR-positive BC36,37. However, according to recent studies the beneficial effect of adjuvant hormone therapy on decreasing local recurrence and death rate was not achieved in BRCA2-associated breast cancer38,39. Moreover, it was demonstrated that gBRCA2 carriers who received adjuvant hormone therapy had a higher risk of death compared to sporadic BC40.

It is also worth noting that gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 have differently affected HER2-low status rate. In general, gBRCA1 was more often related to HER-2 negative status, while gBRCA2 variants were more commonly associated with HER2-low status. To note these data correlate with other study demonstrating relatively high rate of HER2-low status in hereditary cancer33. It was shown that despite the lower frequency of HER2-positive BC among individuals with BRCA1/2 and PALB2 PVs, hereditary BC demonstrated similar proportion of HER2-low expression as compared to sporadic BC33. In the retrospective observational study performed using TCGA data, researchers showed that HER2-low breast cancer associated with defects in HRR related genes demonstrated elevation of HRD score as compared to sporadic BC. Importantly, HER2-low status was mostly associated with mutations in ARID1A, ATM, and BRCA2 genes29. This finding aligns with our results uncovering the close association between gBRCA2 variants and HER2-low status. From the clinical perspective, the presence of HRR mutations in HER2-low tumors opens up potential therapeutic avenues and defines a group of gBRCA2m BC with HER2-low status who can benefit both from PARPi and ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan).

Finally, we found that some particular variants of BRCA1 and BRCA2 were differently related to the age of BC onset, HR and HER2 status. These findings allow us to generate a hypothesis that some BRCA1/2 variants are differently associated with expression of hormone receptors and HER2. However, the interpretation of these data requires further studies.

Limitations of the study

Although our study included a relatively high sample size, it has a cross-sectional design that impacts the limitations of the results. About half of the patients underwent pre-test genetic counselling. There was no available follow up data enabling us to assess patients` outcomes and the efficiency of treatment strategies. We also did not have a whole spectrum of family history data from all patients for deeper analysis of hereditary cancer risks. Due to allocation to one laboratory of pathology and genetic data reports, that could be bias of selection, though the patients from various regions of Ukraine were included in the study.

Moreover, only BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline variants with no CNVs assessment were assessed, without additional analysis of other genes with high penetrance (such as PALB2, TP53 and STK11) and other HRR genes, that could affect the heterogeneity of the comparison group that included non-carriers of gBRCA1/2. In addition, lack of other HRR gene information precludes the analysis of other HRR genes` relation to HER2-low status.

Conclusions

gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 variants differed in their association with breast carcinoma biology, molecular subtype and HER2-status. Patients with gBRCA1 demonstrated the prevalence of TNBC type with predominance of HER2 zero status. In contrast, gBRCA2 carriers had a higher rate of HER-low breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by IRB of Medical Laboratory CSD (Kyiv, Ukraine) for the studies on humans because of the anonymous nature of the retrieved retrospective data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, IRB of Medical Laboratory CSD waived the need to obtain informed consent.

Patient population

This was a retrospective multicenter cross-sectional study that included data about 1412 cases of invasive BC from all regions of Ukraine. Histopathology, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and genetic testing of patients` blood was performed in ISO15189 certified laboratory (CSD LAB) during the period from 2021 to 2024. The following inclusion criteria were applied: women aged 18–75 years old, full set of demographic and clinical data, histologically confirmed invasive breast carcinoma, available data on IHC for ER, PR, HER2 and Ki-67 and FISH in case of IHC2 + HER2 score, as well as available report on testing for germline BRCA1/2 variants. Both primary and metastatic BC cases were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included lack of full set of data, age under 18 or over 75, lobular carcinoma and ductal in situ cases. Depersonalized data was retrieved and used for further analysis. There was no patient involvement in the design of the study. The oncologist obtained consent for testing and secondary data use for research before diagnostics. The collected clinicodemographic data included the patient`s gender, age at BC diagnosis, and location of BC. Demographic characteristics of BC patients enrolled in the study are summarized in Table 1.

Pathology and IHC

Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h and processed automatically (Milestone LOGOS Microwave Hybrid Tissue Processor, Milestone, Italy). Paraffin-embedded blocks were cut at 4 μm thickness (ThermoScientific HM 340E microtome, USA). Sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin using Dako Cover Stainer (Agilent, USA). Histological assessment was performed by trained pathologists according to the WHO classification of breast tumors (5th ed)41. Tumor grade was defined according to the Nottingham grading system. The Nottingham combined histologic grade assessment was based on assigning a score from 1 to 3 to three parameters: amount of tubule formation, extent of nuclear pleomorphism and mitosis count. The final histologic grade was based on a sum of the individual scores of these parameters. Grade 1 was assigned for tumors with final 3–5 score, Grade 2 – for score 6 or 7, and Grade 3 – for neoplasms with 8 or 9 score.

IHC was conducted according to the standard protocol using Autostainer Link 48 (Agilent, USA). The following antibodies were used: ER (Agilent, clone EP1), PR (Agilent, clone PgR 636), HER2 (Agilent, polyclonal, cat.no A0485) and Ki-67 (Agilent, clone MIB-1) to assess the molecular subtype of BC.

For biomarkers assessment the ASCO/CAP guidelines were applied. ER-negative and PR-negative status was defined as < 1% staining in the nuclei via IHC42. ER and PR status was considered positive in case of 1% and higher positive nuclear staining in tumor cells. As for Ki-67, the percentage of cells with immunopositive nuclei was counted and the cut-off of 20% was applied in reporting. HER2 status was graded as negative in case of IHC score 0, HER2-low was assigned when HER2 was assessed as 1 + via IHC and HER2 with IHC score 2 + with no ERBB2 amplification in FISH testing43. HER2-positive tumors included strong positive IHC 3 + cases and HER2 with equivocal results supported by ERBB2 amplification by FISH44.

The following molecular subtypes of BC were defined based on the available data about hormone receptors, HER2 status, Ki-67 expression: Luminal-like (ER positive and PgR positive, HER2 negative (including 0, 1 + and 2 + with no amplification by FISH), triple negative (ER negative, PgR negative, HER2 negative), or HER2 positive (any ER and PgR status, HER2 positive)45,46,47.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing for gBRCA1/2

In this study, all patients underwent germline NGS testing to detect single nucleotide variations (SNV) and indel variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the E.Z.N.A.® Blood DNA Mini Kit (Omega Bio-tek, USA). Quantification of DNA was performed via a spectrofluorometric DeNovix dsDNA Broad Range Assay on a Denovix QFX fluorometer (DeNovix, USA). NGS library preparation was performed using the BRCA Pro Panel kit (AmoyDx, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was set up on the Illumina NextSeq 550Dx platform and NGS data analysis was performed via ANDAS ADXHS-gBRCA v1.5.0 (AmoyDx, China). The bioinformatic data analysis pipeline was provided by sequencing reagent kit manufacturer to be used specifically with AmoyDx reagents (AmoyDx, China). The data analysis pipeline includes the following steps: fastq file quality control, sequence alignment to reference hg19 human genome, variant calling and genetic variant functional annotation. Sequencing and NGS data analysis were performed at CSD LAB, Kyiv, Ukraine. Only genetic variants in heterozygous and homozygous (> 25% depth of sequencing cutoff) states were analyzed to prevent potential mosaic variants from being included in the dataset. The method is validated for clinical diagnostic use and each library preparation batch is evaluated after sequencing to identify artifact patterns, i.e. a singular genetic variant present in all cases within a batch. We do not expect any false positive/false negative results to be included. In this study, only variants of Class 5 Pathogenic (PV) and Class 4 Likely pathogenic (LPV) were considered, defined by ACGS Best Practice Guidelines (2020). Patients who lack PV or LPV gBRCA1/2 were assigned as wild-type (WT) in this study.

Statistical data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 23.1.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2025) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism Version 10.4.1 (627 GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA; www.graphpad.com). Lollipop graphs were constructed via G3viz R package48. Descriptive statistics were provided as Median and interquartile range (IQR; QI – QIII). For comparing continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied. Categorical data were assessed as frequency (%). χ2 test was used to compare frequencies. The P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data represented in the study are deposited at NCBI Sequence Read Archive, BioProject Accession: PRJNA1331801, submissions SUB15651797 and SUB15637069.

Abbreviations

- ADC:

-

Antibody-drug conjugate

- ACGS:

-

Association for clinical genomic science

- ASCO/CAP:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology / College of American Pathologists

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptors

- ESMO:

-

European Society for Medical Oncology

- HBOC:

-

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

- HR:

-

Hormone receptors

- gBRCA1/2:

-

Germline BRCA1/2 variants

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LPV:

-

Likely pathogenic variant

- NGS:

-

next generation sequencing

- PgR:

-

Progesterone receptors

- PV:

-

Pathogenic variant

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

References

Giaquinto, A. N. et al. Breast Cancer Stat. 2022 CA Cancer J. Clin 72, 524–541 (2022).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023).

Barzaman, K. et al. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 84, 106535 (2020).

Ryspayeva, D. et al. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: do MicroRNAs matter? Discov Oncol. 13, 43 (2022).

Gnant, M., Harbeck, N., Thomssen, C. & St Gallen 2011: summary of the consensus discussion. Breast Care. 6, 136–141 (2011).

Ko, H. et al. Is HER2-Low a new clinical entity or merely a biomarker for an antibody drug conjugate? Oncol. Ther. 12, 13–17 (2024).

Cameron, D. et al. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet (London England). 389, 1195–1205 (2017).

Vogel, C. L. et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in First-Line treatment of HER2-Overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1638–1645 (2023).

Slamon, D. J. et al. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 235, 182–191 (1987).

Crocetti, E. et al. Female breast cancer subtypes in the Romagna unit of the Emilia-Romagna cancer registry, and estimated incident cases by subtypes and age in Italy in 2020. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 7299–7304 (2023).

Kang, S. & Kim, S. B. HER2-Low breast cancer: now and in the future. Cancer Res. Treat. 56, 700–720 (2024).

Tarantino, P. et al. ESMO expert consensus statements (ECS) on the definition, diagnosis, and management of HER2-low breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 34, 645–659 (2023).

Tarantino, P. et al. HER2-Low breast cancer: pathological and clinical landscape. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1951–1962 (2020).

Donadio, M. D., Brito, Â. B. & Riechelmann, R. P. A systematic review of therapeutic strategies in gastroenteropancreatic grade 3 neuroendocrine tumors. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 15, 17588359231156218 (2023).

Uzunparmak, B. et al. HER2-low expression in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. Off J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 34, 1035–1046 (2023).

Denkert, C. et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1151–1161 (2021).

Schettini, F. et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 7, 1 (2021).

Tarantino, P. et al. Prognostic and biologic significance of ERBB2-Low expression in Early-Stage breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1177–1183 (2022).

Beral, V. et al. Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet (London England). 358, 1389–1399 (2001).

Armstrong, N., Ryder, S., Forbes, C., Ross, J. & Quek, R. G. W. A systematic review of the international prevalence of BRCA mutation in breast cancer. Clin. Epidemiol. 11, 543–561 (2019).

Schettini, F. et al. Characterization of HER2-low breast cancer in young women with germline BRCA1/2 pathogenetic variants: results of a large international retrospective cohort study. Cancer 130, 2746–2762 (2024).

Nguyen-Dumont, T. et al. Genetic testing in Poland and ukraine: should comprehensive germline testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 be recommended for women with breast and ovarian cancer? Genet. Res. (Camb). 102, e6 (2020).

Gorodetska, I. et al. The frequency of BRCA1 founder mutation c.5266dupC (5382insC) in breast cancer patients from Ukraine. Hered Cancer Clin. Pract. 13, 19 (2015).

Durkie, M. et al. ACGS best practice guidelines for variant classification in rare disease 2023 recommendations ratified by ACGS quality subcommittee on Xxx. R Devon. Univ. Healthc. NHS Found. Trust (2023).

Haffty, B. G. et al. Breast cancer in young women (YBC): prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations and risk of secondary malignancies across diverse Racial groups. Ann. Oncol. 20, 1653–1659 (2009).

Machackova, E. et al. Spectrum and characterisation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deleterious mutations in high-risk Czech patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 8, 140 (2008).

McDevitt, T. et al. EMQN best practice guidelines for genetic testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 479–488 (2024).

Bedrosian, I. et al. Germline testing in patients with breast cancer: ASCO-Society of surgical oncology guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 584–604 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Association between homologous recombination repair defect status and Long-Term prognosis of early HER2-Low breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Oncologist 29, e864–e876 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Distinct clinical and somatic mutational features of breast tumors with high-, low-, or non-expressing human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status. BMC Med. 20, 142 (2022).

Jiang, M., Liu, J., Li, Q. & Xu, B. The trichotomy of HER2 expression confers new insights into the Understanding and managing for breast cancer stratified by HER2 status. Int. J. Cancer. 153, 1324–1336 (2023).

Franzese, O. & Graziani, G. Role of PARP inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy: potential friends to immune activating molecules and foes to immune checkpoints. Cancers (Basel). 14, 5633 (2022).

Goldblatt, L., Coutifaris, P. & Shah, P. D. The frequency of HER2-low breast cancer among BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 10509–10509 (2024).

Zeng, Y., Qian, P., Li, G. & Sun, Y. Differences in survival outcomes between HER2-low and HER2-zero breast cancer across heterogeneous HR expression patterns: a real-world study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 23, 331 (2025).

Hamdard, J. et al. Clinical outcomes in Early-Stage HER2-Low and HER2-Zero breast cancer: Single-Center experience. J. Clin. Med. 14, 2937 (2025).

Ekholm, M. et al. Two years of adjuvant Tamoxifen provides a survival benefit compared with no systemic treatment in premenopausal patients with primary breast cancer: Long-Term Follow-Up (> 25 years) of the phase III SBII:2pre trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2232–2238 (2016).

Abe, O. et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet (London England). 378, 771–784 (2011).

den Brok, W. D. et al. Homologous recombination deficiency in breast cancer: A clinical review. JCO Precis Oncol. 1, 1–13 (2017).

Lips, E. H. et al. BRCA1-Mutated Estrogen Receptor-Positive breast cancer shows BRCAness, suggesting sensitivity to drugs targeting homologous recombination deficiency. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 1236–1241 (2017).

Rennert, G. et al. Clinical outcomes of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. N Engl. J. Med. 357, 115–123 (2007).

Tan, P. H. et al. The 2019 world health organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology 77, 181–185 (2020).

Allison, K. H. et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1346–1366 (2020).

Gamrani, S., Akhouayri, L., Boukansa, S., Karkouri, M. & El Fatemi, H. The Clinicopathological Features and Prognostic Significance of HER2-Low in Early Breast Tumors Patients Prognostic Comparison of HER-Low and HER2-Negative Breast Cancer Stratified by Hormone Receptor Status. Breast J. (2023). (2023).

Wolff, A. C. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: ASCO-College of American pathologists guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 3867–3872 (2023).

Partridge, A. H. et al. Subtype-Dependent relationship between young age at diagnosis and breast cancer survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 3308–3314 (2016).

Arecco, L. et al. Impact of hormone receptor status and tumor subtypes of breast cancer in young BRCA carriers. Ann. Oncol. Off J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 35, 792–804 (2024).

Orrantia-Borunda, E., Anchondo-Nuñez, P., Acuña-Aguilar, L. E. & Gómez-Valles, F. O. & Ramírez-Valdespino, C. A. Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 31–42 (2022). 10.36255/EXON-PUBLICATIONS-BREAST-CANCER-SUBTYPES.

Guo, X., Zhang, B., Zeng, W., Zhao, S. & Ge, D. G3viz: an R package to interactively visualize genetic mutation data using a lollipop-diagram. Bioinformatics 36, 928–929 (2020).

Acknowledgements

None to declare.

Funding

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL, DK, OK, OS and OSul conceived and designed research; SL, AK, AM, OK, OS retrieved and analyzed the data; OK, OS, NK, AM, YaS, NV, KK, AKh, VZ, AA, NO interpreted the results and prepared the figures; SL, DK, AK, OK, OS, NK, YaS, NV, VZ and OSul drafted the manuscript; all the authors contributed to editing, revision, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by IRB of Medical Laboratory CSD (Kyiv, Ukraine) for the studies on humans because of the anonymous nature of the retrieved retrospective data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, IRB of Medical Laboratory CSD waived the need to obtain informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Livshun, S., Kozakov, D., Kruhlykovа, A. et al. Different association of gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 variants with HER2-low status in invasive breast cancer: findings from a Ukrainian study. Sci Rep 16, 619 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30208-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30208-w