Abstract

The COVID-19 infection can cause changes on many organs, but changes in post infection period are not uncommon. The aim of this study is to detect changes in esophageal manometry parameters in post COVID-19 infection period. We reevaluated 84 patients after clinical recovery from COVID-19 disease, who were diagnosed with ineffective esophageal motility, previous to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus. All of the patients enrolled were submitted to reevaluation because of chest discomfort, swallowing problems and dysphagia. The potential coexistence of gastroesophageal reflux disease was excluded clinically by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with narrow band immaging and patohistological analysis and on 24-hours impedance monitoring. Using high-resolution esophageal manometry, and comparing the results to previous functional evaluation before COVID-19 disease, we detected significant lowering of contractile front velocity (CFV), distal contractile integral, prolongation of distal latency and prolongation of peristaltic break size (Break), and influence of infection on distal contractile integral in post rapid swalllows on multiple rapid swallow test (P < 0.07) according to Chicago 4.0 Classification, in all post COVID-19 patients (P < 0.05). In this study, the results of 84 patients included indicate the possible influence of SARS-CoV-2 infection on esophageal motility. The authors find the observation on worsening of changes in patients with preexisting esophageal dysmotility as an interesting finding, that deserves to be shared with clinical and scientific communities, especially in the field of esophageal motility research. Further research is needed in order to confirm these results and elucidate possible mechanisms. This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, under identifier: NCT04988438.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 disease, due to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus is the cause of plethora of symptoms and complications of various organs and organ systems. In up to one half of patients, the COVID-19 disease could present with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, during acute or chronic phase. However, the mechanisms of disease and pathogenetic explanation behind affecting different organ systems in different individuals are yet to be elucidated1,2,3,4,5,6.

In acute disease, the associated GI symptoms and signs are usually mild and self-limiting and include anorexia, diarrhea, transient liver injury, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain or discomfort. A small number of patients can develop clinical signs of acute abdomen, acute pancreatitis, acute appendicitis, intestinal obstruction, bowel ischemia, hemoperitoneum or abdominal compartment syndrome1,2,3,4,5,6. The live virus is detected in all segments of the GI tract and in the stool, it enters the host cells via the receptor complex. The involvement of the GI tract may be due to direct viral injury or an inflammatory immune response, possibly leading to hyperactivation of enteric nervous system, loss of gut mucosal integrity, imbalance of intestinal secretions and malabsorption1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. In addition to GI symptoms during acute COVID-19 disease, various GI symptoms can persist and/or recur during so called post-COVID syndrome or long COVID2,3,4.

Methods

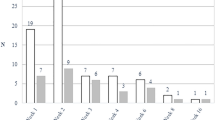

During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we have observed that a certain number of patients, after recovery from COVID-19, may present with recurring troubles during swallowing, chest discomfort and dysphagia. In the period of 30 May 2020 to 30 April 2024, during our study, we included a group of 84 patients (age 20-80y, 48 women and 36 men) with recurring or worsening difficulty with swallowing, chest discomfort and/or dysphagia and who had recovered from mild COVID-19 disease5. Our post COVID-19 patients were categorized as having ambulatory mild disease variant using the WHO minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical classification (score 1–3)5.

All of the patients included in the study (called Post-COVID group) were previously diagnosed with inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility, before infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The second group (called control group) consisted of patients selected blindly and randomly from our pool of patients (selected by random numbers method) with the same esophageal disorder based on symptoms, esophageal monitoring as well as exclusion of other gastrointestinal disorders but who had not contracted COVID-19 infection. The same methods were used to assess symptoms and exclude other GI disorders in both groups. In the control group we had 12 patients (age 21-80y, 7 women and 5 men) which were sampled in the same time period of 30 May 2020 to 30 April 2024. All patients in the control group were set to have esophageal monitoring controls 6 months after the initial testing was done.

Both groups had extensive workup done at the beginning and at the end of our study - clinical investigation, esophageal manometry, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with narrow band immaging and patohistological analysis as well as 24-hour impedance monitoring.

In this way, we wanted to compare timelapse changes in patients without COVID-19 and changes in those with COVID-19.

The patients were recruited consecutively, based on two criteria: documented underlying inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility in our outpatient database, prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2 and persistence/worsening of esophageal symptoms after suffering from mild COVID-19. All patients included in the study underwent the same study protocol consisting of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with NBI and histology, high-resolution manometry and 24 h impedance pH monitoring, as well as clinical examination and routine laboratory findings, before and after infection. According to study design, the aforementioned inclusion criteria did not allow the tunneling selection bias.

The period between recovery from COVID-19 and repeated evaluation of esophageal motility was no longer than six months. During that period, patients included in the study did not change their lifestyle habits and no significant weight gain was noted. According to clinical and laboratory surveillance data, the authors did not observe possible effects on disease progression, other than SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In addition, the presence of GERD was excluded in all participants, using EGD in combination with NBI, pathohistological analysis and 24 h impedance pH-monitoring as current gold standard for diagnosing GERD.

In all patients included in the study, testing for inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility with peristaltic breaks < 5 cm was done on standard procedure in supine position (resting pressure during 30s followed by ten single swallows of 5 ml of water in 30s periods) with the machine of Laborie Medical Measurement Systems MMS – Solar HRM 360° using 36-channel water perfusion system equipped with 36 channel water perfused catheter for esophageal manometry according to Chicago 4 protocol (with software for mathematical adaptation of water perfused catheter to solid state catheters values), as every-day outpatients, before acquiring COVID-19 disease9,10,11,12.

After single swallow tests, we performed the multiple rapid swallow testing with five rapid 5 × 2 ml swallows according to Chicago 4.0 protocol.

Therefore, the evaluation of esophageal motility and 24 h impedance monitoring was performed according to standard protocols which are reproducible, when using the equipment of same technical characteristics for the method.

The potential coexistence of gastroesophageal reflux disease was excluded clinically, by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (Olympus Evis Exera III) in white and narrow-band imaging (NBI) and histology of esophageal mucosa, and on Medical measurement systems MMS 24-hours impedance monitoring using, by using MMS pH monitoring system with 6 impedance and 2 pH monitoring sensors11,12,13,14,15,16.

The catheter was positioned according to standard procedure and according to results of manometric measurement 5 cm above LES. Data analysis was done according to standard protocol with implemented software (Laborie Medical Measurement Systems MMS), and interpretation was done according to Lyon consensus11. All patients were without proton pump inhibitors before and during testing because they had no indication for such kind of therapy11,12,13,14,15,16.

Before COVID-19 infection, we found inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility with peristaltic breaks < 5 cm on MMS-HRM 36-channel perfusion system for esophageal manometry in all participants8]– [9. Before infection, the MMS 24 h-impedance pH monitoring system with 6 impedance sensors and 2 pH sensors was also performed in all patients in order to exclude the potential coexistence of gastroesophageal reflux disease10. All patients suffered a mild form of COVID-19 and were treated as outpatients, in the period from 30 May 2020 to 30 April 2024.

During the following period of six months, the group of 84 patients included in the study reported chest discomfort, troubles during swallowing and dysphagia. In this selected group of symptomatic patients, we repeated the routine laboratory investigation, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with NBI and histology, esophageal motility evaluation, using the same MMS-HRM 36-channel perfusion system for esophageal manometry and the same 24 h impedance pH monitoring9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

All of the patients included in this study signed an informed consent form and the study was approved and done according to ethical principles and suggestions of the Ethics committee of Clinical Hospital Dubrava (Declaration of Helsinki standards).

Statistical analysis was done using software Statistica 2.5 with descriptive statistics and t-test for dependent samples.

Results

The results are presented in Table 1. Using HRM esophageal monitoring, according to Chicago 4.0 Classification, we detected significant lowering of distal contractile integral (DCI) (P < 0.0014), prolongation of distal latency (DL) (P < 0.001), prolongation of peristalic break size (Break) (P < 0.005) and lowering of contractile front velocity (CFV) (P < 0.004), after infection with COVID-19.

We did not find any statistical significance between other parameters [IRP, multiple rapid swallow testing parameters (P > 0.05 for all)] before and after infection in this COVID-19 group.

Interestingly, all patients were classified as inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility with peristaltic breaks < 5 cm before infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus.

After the infection, 16 patients were classified as ineffective esophageal motility with peristaltic breaks 5 cm, while others had persistence of inconclusive ineffective esophageal motility with peristaltic breaks < 5 cm. We did not observe any changes in other measured parameters (Table 1), when comparing the findings, before and after COVID-19, in the same patients. In all patients, integrated relaxation pressure was within normal range before and after COVID-19 infection. We did not find any differences in 24 h pH impedance measured parameters in our patients before and after COVID-19 infection (Table 2).

In the control group there were no differences in CFV, DCI, DL, Break, upper esophageal (UES) resting pressure, lower esophageal sphincter (LES) resting pressure, IRP, multiple rapid swallow testing parameters (P > 0.05 for all) in the six month period (Table 3). We also did not find any differences in 24 h pH impedance measured parameters in our control group.

We also did not find statistically significant difference in age (47.5 ± 1.58years; P < 0.349), sex (men 5, women 7; P < 0.936), CFV, DCI, DL, Break, LES, Multiple rapid swallow test values between COVID-19 group and control group in the beginning study parameters (first measured parameters) (t-test for independent samples P > 0.05).

Using the discriminant function test with the COVID-19 infection as the discriminator, we found a significant difference for CFV (P < 0.0001), DCI (P < 0.0016), UES pressure (P < 0.05), MRS distal contractile integral in post rapid swallows (P < 0.07) after infection beetween the two groups, COVID-19 group and control group (P < 0.0001) (Table 4).

Discussion

Previous studies have described a common association of ineffective esophageal motility with the presence of obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease and the clinical response to proton pump inhibitors depending on the presence of esophageal pathologic acid exposure17. Patients with ineffective esophageal motility and normal acid exposure remain symptomatic and resistant to antireflux therapy mostly. The authors determined that the length of manometrically defined transition zone was wider in esophagitis patients18. In the Shelter et al. seemed that ineffective esophageal motility to be a primary event independent of acid exposure17. Milder variants of ineffective esophageal motility do not progress over time or consistently impact the quality of life, while severe forms are associated with higher esophageal reflux burden, particularly while supine19. In the study where the impact of enhanced triage process on the performance and diagnostic yield of esophageal physiology studies was evaluated, to simplify and to prioritise the waiting lists for esophageal studies during the recovery port COVID-19 and to select the patients who need it20.

This research represents an observational study, revealing the differences in esophageal motility patterns, before and after recovery from COVID-19, in patients with underlying ineffective esophageal motility, previous to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus. Though, the presented research represents a part of the study, registered to ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol under Official Title: „Gastrointestinal Motor Disorders (Esophageal and Anorectal) in Patients After COVID-19 Infection“ under Unique Protocol ID: 2021/1407-03UHD.

Recent studies have documented that the angiotensin converting enzyme II receptor (ACE2) mediates SARS-CoV-2 infection. The ACE2 is also expressed in epithelial and other types of cells along the digestive tube, including the esophagus4. Viral RNA may be detected in the stool even after negative results from respiratory samples. Thus the epithelial line of the esophagus may also represent the port of entry for SARS-CoV-2 virus leading to the damage of various types of cells in the esophageal mucosa. The interactions of epithelial cells and neuroimmune axis are well studied in the spectrum of inflammatory processes of the esophagus, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal infections, elucidating the complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic influences, microbiota changes and etiopathogenetic role of infection with different pathogens8,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. The studies reported that the development of gastrointestinal motoric disorders may be linked to many etiopathogenetic influences, such as GI infections, including H. Pylori24. A plethora of mechanisms, involved in a complex neuro-immune network could lead to gastrointestinal motility disorders, with infectious and non-infectious microinflammation being one of the most prominent14,21,23. Inflammatory mediators, cytokines, leukotrienes and prostaglandins modulate neuroimmune interactions and serotonin activity and could lead to altered motor pathways24.

The possible influence and down-stream effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on esophageal motility is not quite clear. Nevertheless, the results of this study showed the altered/aggravated motoric disorder with changed patterns in the patients with underlying ineffective esophageal motility, after acute COVID-19 disease. From the clinical standpoint, it may be hypothesized that the altered esophageal motility could be the feature of post-COVID syndrome in the predisposed group of patients. In favor of this observation speak the results of a recent study on organoids derived from patients with Barrett’s esophagus28. In this ex vivo model, the authors showed that patients with intestinal metaplasia in the esophagus would have increased potential for virus-epithelial interactions. Speculatively, it may be that the more subtle functional lesions without overt mucosal changes, such as impaired esophageal motility, could also predispose the patients for additional motoric impairment, such as documented in our preliminary report on selected patients, after COVID-19 disease. Furthermore, in their cohort study, Ma et al., have found a strong association between COVID-19 and increased risk of GERD in the long run, noting that the risk of developing GERD did not decrease after 1-year follow up29. It’s plausible that our findings of worsened esophageal motility post infection could be partialy involved in the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of GERD after acute COVID-19 infection.

In order to strengthen the observations of our preliminary report, an expanded study is needed and further analysis of possible mechanisms is warranted.

At the end of this article, we can stress that the previously reported articles have not found progression in ineffective esophageal motility in patients without acid exposure, etc. But, with this fact we can strenghten our hypothesis that the COVID-19 infection had influence in the worsening of ineffective esophageal motility in our post-COVID patients.

This study has several limitations and to address the changes of esophageal motility before and after infection in cases without esophageal motility dysfunction before infection seems to be an interesting area of research. However, in this particular study, the authors focused on the group of patients with preexisting esophageal motility disorder as the comorbidity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The results of this study clearly show the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on preexisting esophageal motility disorder, pointing to this particular group of patients, as prone to worsening of preexisting comorbidity, upon SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Indeed, in our ongoing study we planned to include patients who have developed esophageal dysmotility after COVID-19 infection without esophageal motility dysfunction before infection.

However, the planned study is hampered by several open questions such as the type of study design and the fact that patients with no prior esophageal symptoms would lack the diagnostic work-up, outside the RCT design, which would be ethically questionable.

In spite of relatively small sample size, the authors find the observation on worsening of changes in patients with preexisting esophageal dysmotility as an interesting information, that deserves to be shared with clinical and scientific community, especially in the field of esophageal motility research.

Data availability

All data generated during the study are available upon request from the corresponding author and with the permission of Clinical hospital Dubrava.

References

Gupta, A. et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 1017–1032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3 (2020).

Leal, T., Costa, E., Arroja, B., Goncalves, R. & Alves, J. Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19: results from a European centre. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 33, 691–694. https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000002152 (2021).

Kariyawasam, J. C., Jayarajah, U., Riza, R., Abeysuriya, V. & Senevirante, S. L. Gastrointestinal manifestations in COVID-19. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 115, 1362–1388. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trab042 (2021).

da Silva, F. A. F. et al. COVID-19 Gastrointestinal manifestations: a systematic review. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 53, e20200714. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0714-2020 (2020).

WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, e192–e197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7 (2020).

Cordon-Cardo, C. et al. COVID-19: staging of a new disease. Cancer Cell. 38, 594–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.10.006 (2020).

Buysse, T. M., Bhalla, S. & Kotwal, V. S. Severe Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Ann. Gastroenterolog Dig. Syst. 5, 1057 (2022).

Coles, M. J. et al. It ain’t over ‘Til it’s over: SARS CoV-2 and Post-infectious Gastrointestinal dysmotility. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 5407–5415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-022-07480-1 (2022).

Yadlapati, R. et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0©. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 33, e14058. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14058 (2021).

Alcala Gonzales, L. G., Oude Nijhuis, R. A. B., Smout, A. J. P. M. & Bredenoord, A. J. Normative reference values for esophageal high-resolution manometry in healthy adults: A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 33, e13954. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13954 (2020).

Schlottmann, F., Herbella, F. A. & Patti, M. G. Understanding the Chicago classification: from tracings to patients. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 23, 487–494. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm17026 (2017).

Kessing, B. F., Weijenborg, P. W., Smout, A. J. P. M., Hillenius, S. & Bredenoord, A. J. Water-perfused esophageal high-resolution manometry: normal values and validation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306, G491–G495. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00447.2013 (2014).

Gyawali, C. P. et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon consensus. Gut 67, 1351–1362. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722 (2018).

Gyawali, C. P. et al. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut 73, 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330616 (2024).

Cho, Y. K. How to interpret esophageal impendance pH monitoring. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 16, 327–330. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2010.16.3.327 (2010).

Gwang, H. K. How to interpret ambulatory 24 hr esophageal pH monitoring. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 16, 207–210. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2010.16.2.207 (2010).

Shetler, K. P., Bikhtii, S. & Triadafilopoulos, G. Ineffective esophageal motility: clinical, manometric, and outcome characteristics in patients with and without abnormal esophageal acid exposure. Dis. Esophagus. 30, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dox012 (2017).

Ghosh, S. K. et al. Physiology of the oesophageal transition zone in the presence of chronic bolus retention: studies using concurrent high resolution manometry and digital fluoroscopy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 20, 750–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01129.x (2008).

Gyawali, C. P. et al. Ineffective esophageal motility: Concepts, future directions, and conclusions from the Stanford 2018 symposium. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 31, e13584. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13584 (2019).

Doyle, R. et al. Evaluating the impact of an enhanced triage process on the performance and diagnostic yield of oesophageal physiology studies post COVID-19. BMJ Open. Gastroenterol. 8, e000810. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000810 (2021).

Enck, P. et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 16014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.14 (2016).

Zhang, L., Song, J. & Hou, X. Mast cells and irritable bowel syndrome: from the bench to the bedside. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 22, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm15137 (2016).

Fadgyas-Stanculete, M., Buga, A. M., Popa-Wagner, A. & Dumitrascu, D. L. The relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular changes to clinical manifestations. J. Mol. Psychiatry. 2, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9256-2-4 (2014).

Miyai, H. et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on gastric antral myoelectrical activity and gastric emptying in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 13, 1472–1480. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00634.x (1999).

Herbella, F. A. & Patti, M. G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: from pathophysiology to treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 3745–3749. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3745 (2010).

Tack, J. & Pandolfino, J. E. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 154, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.047 (2017).

Inage, E., Furuta, G. T., Menard-Katcher, C. & Masterson, J. C. Eosinophilic esophagitis: pathophysiology and its clinical implications. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 315, G879–G886. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00174.2018 (2018).

Jin, U. R. et al. Tropism of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 for barrett’s esophagus May increase susceptibility to developing coronavirus disease 2019. Gastroenterology 160, 2165–2168. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.024 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. Risks of digestive diseases in long COVID: evidence from a population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 22, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03236-4 (2024).

Acknowledgements

All patients were on common hospital procedures as outpatients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Žarko Babić, Maja Andabak, Zrinka Rob, Duško Kardum and Marko Banić. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Žarko Babić, Leo Bezdrov and Marko Banić and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babić, Ž., Bezdrov, L., Haber, V.E. et al. Esophageal motility disorders after COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep 16, 1428 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31067-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31067-1