Abstract

We propose a tunable multi-layer graphene surface plasmonic filter in the terahertz band. In this work, we can set the filter type, operation frequency, and pass/stop bandwidth by properly selecting the chemical potential of graphene. Also, higher-order filters are analyzed by cascading multiple filters. All filter parameters are controlled by tuning the graphene chemical potential to manipulate the Fermi level energy of graphene. The equivalent circuit of this device is modeled, and we find a way to design and simulate the proper filter based on the circuit model. Our proposed filter is independent of the polarization angle and the incident wave angle up to 60 degrees. The proposed tunable filter has great potential for spectroscopy, slow light, and filtering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, the terahertz range has found extensive application in fundamental medicine1, biosensing2,3, mobile communication4,5, and spectroscopy. THz Plasmonic metamaterials are interesting to scientists for a wide variety of applications in electromagnetic, optics, photonics, and terahertz fields. In Plasmonic metamaterials, Surface Plasmon Polaritons (SPPs) appear from the interaction between incident light and conduction electrons, manifesting as an evanescent wave that travels along a metal-dielectric surface6. Plasmonic in metals, like gold and silver, concentrate less than the diffraction limit; however, notable energy loss limits application because of the weak binding effect on incoming light and scattering effect7,8,9. Due of these drawbacks, graphene with moderate loss transmission, high conductivity, tuneability by bias voltage without changing the structure, and also the properties of the SPPs generated on graphene are superior to that on metal is a suitable alternative10,11 and these nobles makes Graphene plasmonic metamaterials useful in application like antennas12, lens13, band stop filters14,15,16, band pass filter17, switching18,19 and polarizer20. Frequency multiplexed logic device investigated in21 and indicates a strong potential for utilize in THz digital system. Multiband graphene absorber based on the phase coupled principle presented in22. Also in23 graphene-based solar absorber design using Aluminum, Titanium nitride, and Iron, achieving over 97% absorption in the 1.5–2.5 μm. Plasmonic filters are fundamental for high-speed data processing systems and have been investigated in24,25,26. Terahertz technology also needs filtering devices to choose desired frequency bands and reject thermal radiation, which disrupts sensitive detectors27. Multi-layer filter, like a multi-channel Photonic crystal band pass filter based on the transfer matrix method investigated in28.

Graphene band-pass and band-stop filters are widely used filter types. Recently, researchers designed a monolayer graphene band stop filter with a tunable antidote array, but it is not a wide band filter29. In30, a graphene Plasmon band stop filter based on periodically modulated graphene with a 3.1THz bandwidth was proposed. In31, a terahertz binary coder, Metasrface proposed, which can modulate each passband separately.

For the graphene band pass planar filter, a single-mode band pass filter using a graphene nanoribbon based on a waveguide and a T-shaped resonator was presented32. Also in33, a graphene band-pass planar filter based on comb-shaped nanoribbons is designed for optical integrated components. Moreover, in17, a band-pass filter based on a hybrid graphene non-metallic structure has a suitable performance in 210–230 THz with a quality factor of 3.4.

Multilayer structures are another type of spatial filter which are so vital in optical technology. In34, a graphene multilayer filter based on surface plasmon-induced slow light devices is described. Moreover, a multilayer graphene metamaterial based on Plasmon-induced transparency is presented for switching applications35.

In this work, we propose a multilayer structure for implementing a graphene-based tunable band-pass/band-stop spatial filter. We utilized tuning the chemical potential to control dips that appear from the interaction between terahertz light and graphene layers for designing a dual-functional filter. Moreover, by selecting a suitable amount of chemical potential of graphene, we can use this filter as a band pass or band stop. Also, we proposed an equivalent circuit for the geometrical dimensions of the structure based on the filter specifications. Furthermore, it is shown that by tuning the graphene chemical potential, the frequency response of the filter can be controlled, and a band-pass or band-stop filter can be implemented. Higher-order filters are also implemented based on the proposed filter. Due to the inherent symmetry of the structure, the structure is insensitive to the polarization and the angle of the incident wave.

Methodology

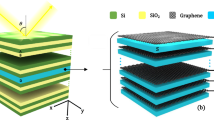

The extended view of the unit cell of the proposed filter is shown in Fig. 1(a). As shown in this figure, it comprises seven graphene layers coated on the silicon (Si) substrate. Layers are symmetrically ordered concerning the middle layer. For the first and second layers, different-length graphene square patches are coated on the substrate. The third layer comprises a plus sign, which is removed from the coated graphene sheet. A graphene plus sign is coated on the substrate for the fourth layer. These layers are positioned at the appropriate distance for the implementation of the tunable spatial filter. Graphene materials can be synthesized using chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Furthermore, this technique allows for the creation of monolayer graphene on a silicon substrate. The hollow cross in our structure can be created by patterning CVD-grown monolayer graphene using the helium ion beam lithography.

The initial significant challenge is that, although high-quality graphene can be produced on a substrate through CVD, effectively separating or exfoliating the graphene from the substrate has proven to be a considerable hurdle. To produce monolayer or few-layer graphene on a substrate, researchers need to address the primary challenges associated with the existing methods. Additionally, achieving a perfectly uniform layer of graphene on the substrate presents another significant obstacle.

The height of the silicon substrate by the relative permeability \(\:{\varepsilon\:}_{r}\:=\:11.9\) and conductivity \(\:\sigma\:\:=\:25\times\:{10}^{-5}\:[S/m]\) is \(\:2\:\mu\:m\). The geometrical parameters of the unit cell are as follows: \(\:{W}_{s}\)=3 μm, \(\:{W}_{g}\)=2.1 μm, \(\:{W}_{g2}\)=2.5 μm, \(\:{W}_{g3}\)=0.25 μm, \(\:{L}_{g3}\)=2.78 μm, \(\:{W}_{g4}\)=0.12 μm, \(\:{L}_{g4}\)=2.5 μm, \(\:{H}_{s1}\)=2 μm, and \(\:{H}_{s2}\)=1.5 μm. Figure 1(b) shows the structure, incident, reflected, and transmitted THz waves.

The interaction between the electric field of the incident THz wave and the free electrons in the graphene layer led to the emergence of Surface Plasmon Polaritons (SPPs) resonance. Consequently, this structure diminishes wave intensity through scattering, resulting in the dip formation in the transmission spectra at resonant frequencies. Therefore, we employed each layer as a medium for wave manipulation at the resonant frequencies. For appropriate chemical potentials of each graphene layer, various modes are coupled together at the resonance frequency. Therefore, a multifunctional filter, which can be band-pass or band-stop, can be implemented. The bandwidth of the filter can be manipulated based on the graphene chemical potential.

The structure of this filter is symmetric and composed of two band-pass filters and a band-stop filter. The hollow cross acts as a band pass, and the solid cross operates as a band-stop filter. The combination of these two filters creates a dual-functional filter. Full-wave simulations are done in CST Microwave Studio. For full wave simulation, we define the unit cell geometry, assign material properties, set up periodic boundary conditions, define two ports for excitation (Zmax is port 1 and Zmin is port 2), and choose a frequency domain solver, Fig. 1(c). The simulation will calculate the metamaterial’s properties like permittivity and permeability, and we can analyze results like reflection and transmission coefficients.

Three-dimensional schematic diagram of unit cell structure based on multilayer metamaterial (a) Separated metamaterial layers. The geometric parameters of the unit cell: \(\:{W}_{s}\)=3 μm, \(\:{W}_{g}\)=2.1 μm, \(\:{W}_{g2}\)=2.5 μm, \(\:{W}_{g3}\)=0.25 μm, \(\:{L}_{g3}\)=2.78 μm, \(\:{W}_{g4}\)=0.12 μm, \(\:{L}_{g4}\)=2.5 μm, \(\:{H}_{s1}\)=2 μm and \(\:{H}_{s2}\)=1.5 μm. (b) The full structure and the incident and transmitted THz light. (C) Floquet ports excitation.

The surface conductivity of graphene can be primarily divided into two components: intra-band conductivity and inter-band conductivity. Within the terahertz frequency range, the intra-band conductivity becomes the predominant factor when the photon energy \(\hslash\omega\)is significantly less than \(\:{2E}_{f}\).

Here, \(\:{2E}_{f}\), \(\:{2K}_{B}\), and \(\:{T}^{\:}\) represent the Fermi energy level, Boltzmann constant, and temperature, assumed to be \(\:{300}^{^\circ\:}K\), respectively. Under these conditions, the contribution from interband conductivity can be disregarded following Pauli’s exclusion principle. Consequently, the surface conductivity of graphene can be effectively represented by its intraband component. The conductivity of graphene is known from the Drude formula as follows36,

Furthermore, e, ℏ, and ω are the electron charge, reduced Planck’s constant, and angular frequency, respectively. \(\:\tau\:\) is the relaxation time, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\:}\)is the mobility of graphene, and \(\:{V}_{f}\)= 106 m/s is the Fermi carrier velocity.

The layer-by-layer analysis of the filter frequency response is depicted in Fig. 2. As shown in this figure, the middle section, including the third, fourth, and fifth layers, behaves like a band-stop filter, as shown in Fig. 2(a). whereas, by adding the second and sixth layers to the middle layers, a wider band-stop filter is achieved, as shown in Fig. 2(b). Finally, considering all layers, a passband filter is achieved, as shown in Fig. 2 (c). More detailed analysis is shown in Fig. 3 based on the E-field distribution on the graphene layers. As shown in this figure, at the band stop frequencies, the E-field concentrates on one or two layers, while at pass band frequencies, the E-field is distributed on all the layers.

Transmission spectra (a) crosses, (b) add two patches, (c) add four patches. Here, chemical potential of layers is \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c1}\)=1.1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c2}\)=0.9eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c3}\)=0.7eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c4}\)=1.2eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c5}\)=0.6eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c6}\)=1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c7}\)= 1.3 eV from left to right respectively.

Equivalent circuit

Based on the proposed structure, each layer of the proposed structure is modeled by a series L-C circuit, which is attached to a transmission line, as shown in Fig. 4(d). For each transmission line, the length \(\:{h}_{i}\) and characteristic impedance \(\:{z}_{i}\) are assumed. Obviously, on the assumption of TEM wave, the length is the substrate thickness, and the characteristic impedances are assumed \(\:{z}_{0}=377{\Omega\:}\) and \(\:\raisebox{1ex}{${z}_{0}$}\!\left/\:\!\raisebox{-1ex}{$\sqrt{{\varepsilon\:}_{Si}}$}\right.=111\:{\Omega\:}\) for air and silicon sections, respectively. Furthermore, the thickness of the first and last substrate is the same and equal to \(\:{h}_{1}=2\:\mu\:m\) and the other substrate thicknesses are \(\:{h}_{2}=1.5\:\mu\:m\). Due to the resonant nature of surface plasmon polaritons on the graphene surface, a series RLC circuit is assumed for the equivalent circuit. As we can see in the Fig. 4(e), the values of \(\:{f}_{1}\), \(\:{f}_{2}\) obtained from equation \(\:{f}_{\:}\)=\(\:\frac{1}{\sqrt{LC}}\) are almost equal to the values of the full wave simulation. Since every layer of the metamaterial filter is coupled together based on the full wave simulation and Fig. 2 of the paper, we were not able to determine every LC resonator.

The values of L and C for each section have been calculated as a function of the dimension and the bias potential of the graphene sheet, as shown in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4(a), for the graphene square patch, the capacitance increases by increasing the patch length as expected. Furthermore, the inductance decreases for higher graphene chemical potential due to an increase in conductivity and the current density, as a result of lowering the kinetic inductance of the structure37.

In Fig. 4(a)Based on the mentioned parameters in Fig. 4, the frequency response of the equivalent circuit is shown in Fig. 5(a). As shown in this figure, the equivalent frequency spectrum is in good agreement with the full wave analysis. Therefore, the filter can be designed based on the equivalent circuit, and the appropriate values of the capacitor and inductor for each layer are determined. Then, the geometrical parameters of each section were extracted based on the plots in Fig. 4. The values of capacitors and inductors used in Fig. 4(d) are depicted in Table 1.

Band-pass filtering application

To implement the band pass filter, the resonance frequencies of each layer have been determined to order the rejection band nulls. These nulls are mainly created due to the interaction of SPPs and the incident THz wave. As mentioned earlier, these resonance frequencies are dependent on the geometrical parameters and the graphene chemical potential. Therefore, by the appropriate selection of these parameters, the rejection band of the filter can be constructed and changed by the chemical potential.

variation. In fact, by adding the same value to all the chemical potentials, a shift in the rejection band can be attained, as shown in Fig. 5(b). In this figure, the blue diagram shows the attained band pass filter in which the chemical potential of each layer is \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c1}\)=1.1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c2}\)=1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c3}\)=0.7eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c4}\)=1.2eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c5}\)=0.6eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c6}\)=1 V, \(\:\mu\:c7=1.3eV\:\)from left to right, respectively. Here, the pass band includes [2.6–3.49] THz. If 0.15 eV is added to the graphene layer’s chemical potential, the red diagram is attained, which shows a pass band in the frequency range of [2.85–3.55] THz. Accordingly, the addition of 0.3 eV to all the graphene chemical potentials, a pass band in the frequency range [3.32–3.88] THz will be attained.

(a) depicts the results of the equivalent circuit model and electromagnetic analysis. There is a suitable overlap between them, and (b) the transmission spectra with adding different values of chemical potential, ranging to all layers from 0 to 0.3 eV for a seven-layer graphene metamaterial structure.

We calculate the normalized mean absolute error in the degree of closeness of the full-wave and circuit simulation. Also, we can see the extent to which the two answers overlap. normalized mean absolute error is calculated from the following formula.

Band-stop filtering application

As we mentioned earlier, the resonance of the surface plasmon polaritons due to the incident wave results in an absorption peak. Therefore, by managing them, the band-stop filter can be implemented. The stop band width and other characteristics of the filter depend on the geometrical parameters of the structure and chemical potential of the graphene sheets. Therefore, the frequency response of the filter can be manipulated. In Fig. 6(a), it is shown the transmission spectrum of the filter is shown on the assumption of is \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c1}\)=0.4eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c2}\)=0.5eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c3}\)=1.2eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c4}\)=0.3eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c5}\)=1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c6}\)=0.6eV, \(\:\mu\:c7=0.3eV\) are the graphene chemical potentials from left to right, respectively.

Here, the geometrical parameters are set similar to Fig. 5(a). In Fig. 6 (b), it is shown that the equivalent circuits are approximately the same transmission spectrum as the full wave simulation.

The corresponding values of capacitors and inductors are depicted in Table 2. Similar to band-pass filters, the addition of graphene chemical potential to all the graphene layers will result in a shift in the transmission spectrum stop band. As shown in Fig. 6(c), the addition of each 0.15 eV to the chemical potential of graphene layers will result in approximately 0.4THz frequency shift in the center frequency of the band stop filter.

Based on what has been shown so far, the band pass and band stop filter can be implemented based on the selection of graphene chemical potential in the frequency range of [1.5-5] THz. In Fig. 7, the appropriate chemical potential band for the implementation of band pass and band stop is shown.

In the second state, if we select the chemical potentials with no overlap, we have some dips in desire frequency, and the device acts as a band stop filter, and they shift by changing the bias voltage of graphene. Figure 6(a) we can see the equivalent circuit and EM waves. Moreover, by adding a constant chemical potential from 0 eV to 0.3 eV to all layers, the stop band is shifted from 2 THz to 2.41THz at first of the band and 3.81 THz to 4.38THz at the end of the band, as shown in Fig. 6(b).

In Fig. 7, we can understand the process of selecting the chemical potential for each layer in two states: band pass and band stop.

Higher order filters

Higher-order filters are realized based on a cascade of several proposed filters with a specific air gap, as shown in Fig. 8. As shown in this figure, for the second order (Fig. 8(a)) and third order filter (Fig. 8 (b)) all the parameters of the filters and the air gap distances are.

assumed the same. Simulations show that the frequency response is independent of the air gap distance. The transmission spectra of the filters are shown in Fig. 8(c). As shown in this figure, the pass band of the filters remains unchanged while the slope of the cutoff band increases with increasing filter order. Further discussion on this will be provided in later sections.

Control bandwidth

As we mentioned earlier, the chemical potential of the graphene layers can be used to control the bandwidth of the filter. Assumed the third-order filter as discussed previously, and the transmission spectra are shown in Fig. 8. In this filter, the chemical potential of the graphene layers of the first, second, and third filters is assumed to be the same. This assumption is named “state 1” in Fig. 9(b), and the transmission spectra are plotted. Now consider the value \(\:\varDelta\:=0.3ev\). If all the chemical potential values of the first filter layers (A) are summed with the \(\:\varDelta\:\:\)value. Also, the corresponding values of the second filter(B) remain unchanged, while all the chemical potential values of the third filter layer(C) are subtracted from the \(\:\varDelta\:\:\)value. Figure 9(a). The corresponding transmission spectra based on this assumption are named “state 2” and plotted in Fig. 9(b). As shown in this figure, the lower passband corresponds to state 2. Simulation results show that the pass band decreases for higher values of \(\:\varDelta\:\). The values of the chemical potential for each layer of the graphene for the above simulation are as follows: \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c1}\)=1.1eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c2}\)=0.9, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c3}\)=0.7eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c4}\)=1.2eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c5}\)=0.6eV, \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c6}\)=1 eV, and \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{c7}\)=1.3 eV from left to right, respectively. State 1 in the figure below shows the band pass of three filters that cascaded to each other. Now, if a certain amount of chemical potential is added to the chemical potential of layers of filter A and subtracted from the chemical potential of layers of filter C, while filter B remains unchanged, the passband of the filter can be changed. State 2 in the figure shows this change.

The study of polarization and the angle of incident wave

In this section, we study the influence of the incident plane wave angle and polarization on the transmission spectra of the proposed filter. In Fig. 10 (a), the transmission spectra of the first-order filter are shown as a function of the polarization angle. As shown in this figure, a relatively unchanged transmission spectrum has been attained for the polarization angles of 0°, 45°, and 90°, which reveals the appropriate performance of the structure for TE and TM incident plane waves due to the asymmetric of the structure. Similarly, the analysis shows that the transmission spectra remain unchanged up to 60° incident angle, as shown in Fig. 10(b). Moreover, by changing the incident angle from 0 to 60 degrees, the filtering behavior of the presented filter did not change. Figure 10(a), (b) shows the independence of the structure from the incident angle of the plane wave and its polarization.

Performance analysis

At the first step, the analysis of the group delay for the proposed third-order filter has been done. For this, the transmission amplitude, phase, and group delay are shown in Fig. 11(a), (b), and (c), respectively. As shown in this figure, in the frequency range of [2.5–3.3]THz, a relatively flat transmission spectrum have been attained. The analysis of the group delay shows a relatively flat group delay with the variation of \(\:\pm\:0.3ps\), as shown in Fig. 11.

Next, the roll-off factor was calculated for the first, second, and third-order band-pass filters. Figure 12 shows the transmission for the first-order, second-order order and third-order band pass filter in blue, red, and yellow lines, respectively. As shown in this figure, the higher ascending and descending slopes belong to higher-order filters, as expected. The values of these slopes are depicted in Table 3. In Fig. 12, as we know, according to the theory, in a filter, as the order of the filter increases, the slope of the graph increases from the pass state to the stop state. Here, by placing three same filters in series, the order of the filter increases, and the slope of the descending and ascending graph increases and as shown. Moreover, it improved the rejection band of the filter.

The performance comparison of the proposed structure and other structures reported in the literature is shown in Table 4. As mentioned in this table, the proposed filter reveals reconfigurability and tunability in a wide THz bandwidth.

Potential spectroscopy application

One of the main potential applications of the proposed filter is concentrated on spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 13, a bolometer, which is positioned behind the filter, measures the pass band spectrum of the incident wave, which can be controlled by tuning the chemical potential of the graphene based on an FPGA. Therefore, a THz spectrometer can be implemented at a lower cost.

Discussion

In this paper, we proposed a dual-functional plasmonic metamaterial graphene filter in the terahertz band for the first time. Based on the equivalent circuit that we proposed, we could design the dual-mode filter using a transmission chart. Due to the interaction between graphene layers and terahertz waves, surface Plasmon resonance was created, and by tuning the chemical potential, the resonance frequency was justified, and the transmission spectra of the filter can be controlled. In the next step, we cascade two or three filters together to increase the order of the filter. Moreover, this structure is independent of the polarization angle and the incident angle of waves. Ease of implementation, in addition to superior performance, makes this structure a good candidate for spectroscopy and filtering applications.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from P.K. but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of P.K. (email: pooria_kabiri@elec.iust.ac.ir).

References

Gezimati, M. & Singh, G. Terahertz imaging and sensing for healthcare: current status and future perspectives. IEEE Access. 11, 18590–18619. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3247196 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Highly sensitive detection of malignant glioma cells using metamaterial-inspired THz biosensor based on electromagnetically induced transparency. Biosens. Bioelectron. 185, 113241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2021.113241 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Label-free measurements on cell apoptosis using a Terahertz metamaterial-based biosensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 241105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4954015 (Jun. 2016).

Chaccour, C. et al. Seven defining features of Terahertz (THz) wireless systems: A fellowship of communication and sensing. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 24 (2), 967–993. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2022.3143454 (2022).

Akyildiz, I. F., Han, C., Hu, Z., Nie, S. & Jornet, J. M. Terahertz band communication: an old problem revisited and research directions for the next decade. IEEE Trans. Commun. 70 (6), 4250–4285. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2022.3171800 (2022).

Gramotnev, D. K. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Plasmonics beyond the diffraction limit. Nat. Photonics. 4 (2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2009.282 (2010).

Lee, T. W., Lee, D. E., Lee, Y. J. & Kwon, S. H. Three-Dimensional Plasmonic Ruler Based on Silver Metal Blocks, in Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Pacific Rim, 2015, p. 26P_64. [Online]. Available:, 2015, p. 26P_64. [Online]. Available: (2015). https://opg.optica.org/abstract.cfm?URI=CLEOPR-2015-26P_64

Yang, Y., Kravchenko, I. I., Briggs, D. P. & Valentine, J. All-dielectric metasurface analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency. Nat. Commun. 5 (1), 5753. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6753 (2014).

Chai, Z., Hu, X., Yang, H. & Gong, Q. Chip-integrated all-optical diode based on nonlinear plasmonic nanocavities covered with multicomponent nanocomposite, 6, 1, pp. 329–339, doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2016-0127

Yi, Z. et al. Fabrication of ZnO@Ag3PO4 Core-Shell nanocomposite arrays as photoanodes and their photoelectric properties. Nanomaterials 9 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9091254 (2019).

Guiqiang, L. et al. Semiconductor-enhanced Raman scattering sensors via quasi-three-dimensional Au/Si/Au structures. Nanophotonics 8 (6), 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0078 (2019).

Mashayekhi, M., Kabiri, P., Nooramin, A. S. & Soleimani, M. A reconfigurable graphene patch antenna inverse design at Terahertz frequencies. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 8369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35036-4 (2023).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (18), 3966–3969. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3966 (Oct. 2000).

Mohammadi, G., Orouji, A. & Danaie, M. Highly compact tunable hourglass-shaped graphene band-stop filter at Terahertz frequencies. Results Opt. 13, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2023.100575 (2023).

Esfandiyari, M. et al. Tunable Terahertz filter/antenna-sensor using graphene-based metamaterials. Mater. Des. 220, 110855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110855 (2022).

Li, C., Zhongyin, X., Wei, L. & Zou H. and Tunable multiband band-stop filter based on graphene metamaterial in THz frequency, J. Electromagn. Waves Appl., vol. 32, no. 18, pp. 2481–2489, Dec. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/09205071.2018.1518161

Mirnia, S. E. & Lail, B. A. Dynamically tunable reflecting near-infrared bandpass filter based on a hybrid graphene–nanometallic structure. Appl. Opt. 59 (18), 5608–5614. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.391030 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Polarization-sensitive triple plasmon-induced transparency with synchronous and asynchronous switching based on monolayer graphene metamaterials. Opt. Express. 28 (24), 36771–36783. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.410417 (2020).

Gao, E. et al. Terahertz multifunction switch and optical storage based on triple plasmon-induced transparency on a single-layer patterned graphene metasurface. Opt. Express. 28 (26), 40013–40023. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.412061 (2020).

Sarker, D., Nakti, P. P., Tahmid, M. I., Mamun, M. A. Z. & Zubair, A. Terahertz polarizer based on tunable surface plasmon in graphene nanoribbon. Opt. Express. 29 (26), 42713–42725. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.444706 (2021).

Asgari, S. & Fabritius, T. Frequency-multiplexed tunable logic device based on Terahertz graphene-integrated metamaterial composed of two circular ring resonator array. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 28920. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14311-6 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Investigation of multiband plasmonic metamaterial perfect absorbers based on graphene ribbons by the phase-coupled method. Carbon N Y. 141, 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2018.10.002 (2019).

Aliqab, K. et al. Graphene metamaterial solar absorber using Al-TiN-Fe for efficient solar thermal energy conversion and optimization using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31643. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80485-0 (2024).

Setayesh, A., Mirnaziry, S. & Abrishamian, M. Numerical investigation of tunable Band-pass\band-stop plasmonic filters with Hollow-core circular ring resonator. J. Opt. Soc. Korea. 15, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.3807/JOSK.2011.15.1.082 (Mar. 2011).

Sheng, S., Li, K., Kong, F. & Zhuang, H. Analysis of a tunable band-pass plasmonic filter based on graphene nanodisk resonator. Opt. Commun. 336, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2014.10.009 (2015).

Zhang, L., Yang, J., Fu, X. & Zhang, M. Graphene disk as an ultra compact ring resonator based on edge propagating plasmons, Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 103, no. 16, p. 163114, Oct. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4826515

Schuster, F. et al. Apr., Broadband terahertz imaging with highly sensitive silicon CMOS detectors, Opt. Express, vol. 19, pp. 7827–7832, (2011). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.19.007827

Liu, Y. & Yi, L. Tunable Terahertz multichannel filter based on one-dimensional superconductor-dielectric photonic crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 223102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4904054 (Dec. 2014).

Wang, W., Yang, D., Qian, Z., Xu, C. & Wang, C. Tunable Terahertz band-stop filter based on self-gated graphene monolayers with Antidot arrays. Opt. Commun. 427, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2018.06.015 (2018).

Shi, B. et al. Tunable Band-Stop filters for graphene plasmons based on periodically modulated graphene. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 26796. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26796 (2016).

Gong, Y. et al. Terahertz binary coder based on graphene metasurface. Carbon N Y. 184, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.08.011 (2021).

Mohammadi, G., Orouji, A. A. & Danaie, M. A tunable narrow single-mode bandpass filter using graphene nanoribbons for THz applications. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 21217. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71869-3 (2024).

Deng, G., Zhao, T., Yin, Z. & Yang, J. Bandpass filter based on comb shaped graphene nanoribbons. OSA Contin. 2, 2614–2622. https://doi.org/10.1364/OSAC.2.002614 (2019).

Sarker, D., Nakti, P. P. & Zubair, A. Graphene metamaterials-based plasmon-induced Terahertz modulator for high-performance multiband filtering and slow light applications. Opt. Express. 32 (6), 9442–9455. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.516142 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Simultaneous switching at multiple frequencies and triple plasmon-induced transparency in multilayer patterned graphene-based Terahertz metamaterial. New. J. Phys. 22 https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ab9e8a (Aug. 2020).

Xu, K. D., Li, J., Zhang, A. & Chen, Q. Tunable multi-band terahertz absorber using a single-layer square graphene ring structure with T-shaped graphene strips, Opt. Express, vol. 28, pp. 11482–11492, Apr. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.390835

Mousavi, S. H., Williamson, I. A. D. & Wang, Z. Kinetic inductance driven nanoscale 2D and 3D THz transmission lines. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 25303. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25303 (2016).

Yao, Z. et al. Jun., Design and analysis of terahertz filters based on multilayer metamaterials, Appl. Opt., vol. 61, pp. 5799–5805, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.458369

Asl, A. B., Rostami, A. & Amiri, I. S. Terahertz band pass filter design using multilayer metamaterials. Opt. Quantum Electron. 52 (3), 155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-020-02268-x (2020).

Mohammadi, G., Orouji, A. A. & Danaie, M. Highly selective single-mode graphene bandpass filter based on Wilkinson power divider structure. Diam. Relat. Mater. 145, 111141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2024.111141 (2024).

Mohammadi, G., Orouji, A. & Danaie, M. A dual-band tunable Terahertz bandpass filter using an E-shaped graphene resonator. Opt. Quantum Electron. 57 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-024-07906-2 (Dec. 2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K. and A.S.N conceived the idea. P.K. designed and analyzed the graphene metamaterials. Finally, P.K. wrote the manuscript and A.N. supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabiri, P., Nooramin, A.s. Proposing a novel structure for the implementation of a graphene metamaterial-based tunable band pass/stop spatial THz plasmonic filter. Sci Rep 15, 45093 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31336-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31336-z