Abstract

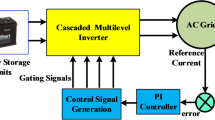

In this paper, a modified hysteresis band logic-analog controller with capacitors balancing ability is proposed. A multi-function five-level grid-tied inverter is investigated, which can be used to inject power into the grid and act as an active filter, simultaneously. It is also capable of absorbing active power to act as a storage system using batteries on the DC link and reactive power compensation to some extent. The new hysteresis band controller has been implemented on a conventional 5-level converter, based on the current injection method. In addition, this controller is also capable of balancing the voltage of the capacitors by selecting appropriate switches related the desired voltage vector. The proposed controlling method acts in the time domain and no need for complex transformations; furthermore, it has a high processing speed due to the utilization of logic gates. Moreover, due to the lack of need for a microcontroller or DSP, there is no halt phenomenon or delay in the execution of software loops. In this paper, power injection into the grid and active filtering ability have been investigated. To verify the proper operation, the simulation results as well as the laboratory 350 W prototype results are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An inverter plays a crucial role in transforming DC power to AC power. Multilevel inverters offer advantages such as lower total harmonic distortion (THD), reduced switching voltage stress, and more compact output filters than other types of sine-wave inverters1,2,3. Consequently, they are frequently used in renewable energy generation, HVDC transmission, active power filtering (APF), high-power motor drives, flexible AC transmission (FACTs), and several other applications4,5,6. Traditional multilevel inverter (MLI) designs include the cascaded H-bridge (CHB)7, neutral-point-clamped (NPC)8, and flying-capacitor (FC)9 inverters. Among the various multilevel inverter configurations, the cascaded H-bridge (CHB) inverter stands out due to its excellent output performance10,11.

Grid-tied inverters play a vital role in enabling the integration of renewable energy sources. They connect distributed generators (DGs) to the existing grid or a microgrid12. Generally, grid-connected inverters are divided into two categories: transformer-based and transformerless. While transformer-based inverters offer galvanic isolation, transformerless inverters are preferred due to their smaller size, enhanced efficiency, and affordability13,14. The features of grid-connected inverters (GCIs) closely resemble those of isolated inverters regarding circuit parameters, with the main differences lying in their control and protection mechanisms. As the adoption of renewable energy continues to rise, GCIs have increasingly become a central area of research.

GCIs can be improved by advancements in their topology or control systems. Both aspects of GCI hold high significance. This research contributes to the control field by improving power handling capacity, capacitor voltage balancing, and reducing total harmonic distortion (THD) of the entire system. The control typically performs three main functions: synchronization, current regulation, and harmonic compensation. The synchronization component in some methods captures the grid voltage phase and relays it to the current controller. This captured phase is utilized in the direct-quadrature-zero (DQZ) transformation and the generation of reference signals. The current controller oversees the current and generates a current that corresponds with the grid voltage, thereby enabling active power transfer12. The controller needs to be designed to produce pure sine-wave currents even when harmonics are present in the grid; however, the inverter controller does not successfully mitigate these harmonics, leading to inverter output currents that include low-order harmonics. As a result, harmonic compensators are utilized in conjunction with the current controller to reduce the harmonic contents in the grid current12.

Numerous control strategies have been examined for single-phase converters, including proportional integral derivative (PID), proportional resonant (PR), and current hysteresis controls, among others15,16,17. Although these linear controllers have their advantages, they suffer from slow dynamic responses. Consequently, several advanced control techniques, such as model predictive control (MPC), have been investigated and advocated in scholarly literature, particularly due to the advent of high-performance microprocessors, digital signal processors (DSPs), and field-programmable gate array (FPGA) technologies18,19. To manage the variable switching frequency associated with model predictive controllers (MPCs), various approaches, such as optimal switching sequence, have been suggested for single-phase converters20,21.

Low-frequency control methods such as nearest-level controllers (NLC), selective harmonic elimination pulse width modulation (SHEPWM), and selective harmonic mitigation (SHM) are commonly utilized techniques22,23,24. In the SHE approach, the inverter’s optimal switching removes lower-order harmonics by resolving complex non-linear transcendental equations. The primary challenge associated with this control method is that solving these intricate equations is time-intensive and quite complicated. Furthermore, implementing it in a closed-loop operation presents additional difficulties. For NLC, the switching frequency aligns with the power frequency, making it relatively straightforward to implement. However, its main disadvantages include a reduction in voltage levels as the modulation index changes and an increase in the total harmonic distortion (THD) values of the load voltage and current. To merge the benefits of both NLC and SHE, a new control method is introduced in25 which combines these two techniques.

To overcome to some of the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a novel logic-based hysteresis controller to a grid connected five level inverter which has the following merits:

-

Low-cost and fast operation No need for high-speed or expensive microprocessors; the controller is implemented using ordinary logic gates, comparators, and analog devices, ensuring high processing speed.

-

Robust and reliable The control is immune to noise and electromagnetic interference (EMI), with continuous operation and no halting.

-

Simple implementation Time-domain operation eliminates the need for complex transformations, while a single DC source (solar panels, batteries, or microgrids) is sufficient.

-

Accurate current control Based on current injection, the hysteresis controller regulates inverter switching to ensure the injected current follows the reference under all operating conditions.

-

DC-link voltage balancing Proper selection of switching states allows balancing of capacitor voltages, while still producing all output voltage levels even if capacitors are initially unbalanced.

-

Proper switching and reduced losses Proportional hysteresis band reduces switching frequency at higher voltage and current levels, lowering switching losses and harmonic content.

-

Bidirectional power flow and versatile applications Suitable for grid-tied inverters, active power filters, active and reactive power injection, and energy storage systems.

The structure of the paper is outlined as follows: "Studied grid-tied five-level inverter" section provide the studied topology. "Proposed logic based modified hysteresis band controller" section presents a comprehensive explanation of the proposed logic-based controller. "Simulation and experimental results" section features the simulation and experimental analysis of the proposed topology. A comparative study with other studied controlling method is conducted in "Comparison study" section. Finally, "Conclusion" section provides the conclusion of the work.

Studied grid-tied five-level inverter

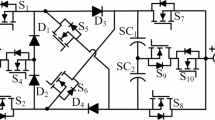

In this section, the five-level active power filter is reviewed. Figure 1 depicts the studied structure which is based on multi-level inverter (MLI). As can be seen from the figure, the topology consists of eight power switches S1-S8, Sxa, Sxb, Sya, Syb, and two capacitors C1, C2. Only a brief explanation of the topology studied is provided in this section.

The switching logic of the topology is tabulated in Table 1. The operating modes of the five-level active power filter are explained here.

Voltage level (0Vin):

Zero voltage level (see Fig. 2a and d) can be achieved either by switches S1 and S3 for positive current flow or switches S2 and S4 for negative current flow.

Voltage level (+ 1Vin):

This voltage level (see Fig. 2b) can be obtained through Switches S2, S3, Sya and Syb.

Voltage level (+ 2Vin):

The voltage level is realized (see Fig. 2c) through switches S2, S3, Sxa, and Sya.

Voltage level (− 1Vin):

As shown in Fig. 2e, the output is generated by S1, S4, Sxa, and Sxb.

Voltage level (− 2Vin):

Finally, this output voltage is achieved (see Fig. 2f) through switches S1, S4, Sxa, and Sya.

In Fig. 2, the different operating modes of the topology are presented.

Proposed logic based modified hysteresis band controller

In this section, the proposed logic-based controller is discussed. Figure 3 depicts the proposed Controller and controlling method layout. The following assumptions are made:

-

Switching controls is done to make \(V_{d1} = V_{d2}\).

-

To achieve appropriate performance, the controller must \(V_{d1} + V_{d2} > V_{m}\)

-

To compensate for harmonics caused by the non-linear load, \(I_{m,ref} > i_{o}\)

The decision to switch is made at a fixed frequency and at every time instant; first, the operating point is determined by comparing the PCC voltage (or Vs) with the voltage levels Vd1 and Vd1 + Vd2. For this purpose, \(\left| {V_{s} \left( t \right)} \right|\) is employed. This is depicted in Fig. 4. M1 and M2 are the two operating regions that are caused in this topology (five-level), and the selection logic is shown in Fig. 5.

If \(\left| {V_{s} \left( t \right)} \right|\) is in the M1 region, the switching vectors are chosen from (0 and Vd1) or (− Vd1 and 0). If \(\left| {V_{s} \left( t \right)} \right|\) is in the M2 region, the switching vectors are chosen from (Vd1 and Vd1 + Vd2) or (− Vd1 and − Vd1 − Vd2). The reason for these selections of the switching vectors is to create a minimum voltage difference between the inverter output and PCC voltage, which lowers the current ripple. Ka in Fig. 5 is the attenuation coefficient, which is 0.01 here.

At every time instant in which the switching state changes, 2 voltage vectors are selected according to the aforementioned explanations. To determine these voltage vectors, besides M1 and M2, the comparison of the is with the reference current is needed, which is carried out by the modified hysteresis band method. In the modified method, which is done by simple circuits, the band limitations are proportional to the magnitude; the higher bandwidth is selected for a higher magnitude and vice versa. While in the conventional hysteresis band method, a fixed band width is employed for different magnitudes. A change in the bandwidth causes changes in the switching frequency. Bandwidth increases for higher magnitude, and hence the switching frequency decreases, which decreases switching losses. In addition, the maximum frequency variation in the switching is controlled by a fixed frequency. These explanations, along with the modified hysteresis band method, are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. In Fig. 7, fmax is the maximum variation in switching frequency, which is 100kHz in this case. In Fig. 7, Cb is defined as a coefficient that determines the hysteresis band boundary, which is 5% in this paper.

For the selection of the switching vector, M1 or M2, L, or H and the sign of the PCC voltage is needed. Then, for appropriate switching, the various states and switching vectors in Table 2 are used. Table 2 presents the inverter output voltage with respect to the link voltage and switches Sn, Sn1, Sp, and Sp1.

Where, VLink is obtained from the previous stage, which is called level switches here. From Ps (average injected power to the grid), which is calculated by φ, the capacitors’ charging and discharging states can be determined, and are tabulated in Table 3.

Assuming that the proposed control system could balance the capacitors Cd1 and Cd2 Voltage, therefore: \({\text{V}}_{{{\text{d1}}}} \simeq {\text{V}}_{{{\text{d2}}}} \simeq {\text{V}}_{{\text{d}}}\). Hence, there are five voltage vectors, including the zero volage vector. Vd or − Vd could be chosen by Vd1 or Vd2, and this selection depended on the charge levels of capacitors Cd1 and Cd2 and current flow direction, is, in order to keep the capacitors’ voltage balanced. The voltage vectors are: V1 = Vd, V2 = 2Vd, V3 = − Vd, V4 = − 2Vd, V5 = 0. The logic diagram of voltage vectors and gate signals is shown in Fig. 8. In Fig. 8, Bx and By are related to the capacitors’ voltage balance and controlled by that logic.

Simulation and experimental results

The proposed topology’s performance is evaluated through simulation results carried out in PSCAD/EMTDC software and experimental results. A 350 W prototype of the 5-level active power filter is built in the laboratory.

Simulation results

In this section, the simulation results of the 5-level active power filter with the proposed control method are provided. The components values and their ratings are listed in Table 4.

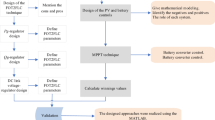

In Fig. 9, the flowchart of the controlling method is presented. The whole process is held true if the input supply like, PV panel’s power is higher than the nonlinear/linear load absorbing power.

The non-linear load current is shown in Fig. 10. The proposed method is tested under a laboratory prototype of about 350 W. The amplitude of the non-linear load current is about 2.5 A. As can be seen from the figure, the rectifier loads absorb non-sinusoidal (needle type) current from the grid.

In Fig. 11, the waveforms of the voltage and current of the grid before employing the proposed controlling method of the active power filter are presented. As can be seen, the current waveform of the grid is non-sinusoidal, although the voltage waveform is sinusoidal. Also, in Fig. 11c, the current waveform of the grid with the proposed controlling method for the 5-level active power filter is shown. It is obvious from the figure that the current waveform of the grid is close to the sinusoidal waveform, although the load absorbs non-sinusoidal current from the grid.

In Fig. 12, the output voltage waveform of the 5-level active power filter studied is depicted. Also, the voltage waveforms of the inverter and the grid is shown in this figure.

In order to facilitate the comprehension of the benefits provided by the proposed control method, Table 5 presents a comparison between the RMS, THD and PF of the load and grid currents with the proposed control method compensation for both the non-linear loads scenarios. As it can be seen, the THD values decreases. It is obvious from Table 6 that the current THD of the grid reduced from 140 to 5.3% with the proposed modified logic-based method.

In Fig. 13, the FFT of the non-linear load current and the grid current with the proposed controller is provided.

In the Fig. 14, the current waveforms of the MLI, the grid, and the load with respect to each other is shown. As can be seen from the figure, the multi-level inverter can also inject the load and the grid current to compensate for the current that the nonlinear load absorbs from the grid.

Experimental results

In this section, the experimental results are provided to confirm the accuracy of the claims provided in the previous sections. Thus, the results of the laboratory prototype are included here. The experimental setup of the prototype is shown in Fig. 15.

In Fig. 16, the experimental results of the voltage of the grid and the multi-level inverter, the current of the grid without the proposed controller, are presented. As it is obvious, without the controller, the grid current is not sinusoidal and is the same as the load current.

In order to demonstrate the performance of the proposed control method and compensator role, the waveforms of the grid current, inverter current, and the load current experimental results with respect to each other are shown in Fig. 17. As it is obvious, the current of the grid with the proposed controller more resembles the sinusoidal waveform. In Fig. 17a, the inverter injecting current with respect to the grid compensated current is shown, which is near a sine wave. In Fig. 17b, the grid compensated current with respect to the load current is shown. And finally, in Fig. 17c shows the inverter injecting current with respect to the load current.

In Fig. 18, the capacitors Cd1 and Cd2 voltage is shown. The capacitors voltage is almost same and equal to about 180 V.

Comparison study

The suggested logic-based hysteresis band method is also evaluated against six control methods discussed in26,27,28,29,30,31. This evaluation considers the type of controller, the necessity of weighting factors, the number of weighting factors required, the number of sensors needed, the requirement for an additional controller to manage DC capacitor voltages, and the method used for generating reference filter currents, as detailed in Table 6. It is clear that the proposed logic-based hysteresis band method offers advantages such as a structure that does not require weighting factors, decreased controller complexity, as it does not necessitate an additional control loop for regulating the DC capacitor voltage or generating reference filter currents, and it also eliminates the need for a microprocessor like STM. Unlike the methods in26,27,28,29, the method proposed in this study and those in30,31 do not require an additional controller for DC capacitor voltage regulation. However, the control approach in30 does require a weighting factor and an extra sensor compared to the method being proposed here. In contrast to the reference filter current generation in the proposed method, the approaches presented in26,27,28,29 involve substantial computations, additional transformations, and the use of low-pass and high-pass filters.

The proposed hysteresis method determines the reference current, proportional to the reference current magnitude and real current magnitude, with increasing the current, the hysteresis band increases. The output voltage level is created by four regions explained above and the voltage balancing condition. Therefore, preventing unstable switching due to rapid voltage or load current variations. In the proposed method, the frequency variations are somehow less.

Conclusion

This paper introduced a multifunctional five-level grid-tied inverter capable of power injection, active filtering, reactive power compensation, and energy storage support through DC-link batteries. A novel logic-based hysteresis band controller was proposed to achieve precise current injection, capacitor voltage balancing, and reduced switching losses without relying on digital processors. The method effectively injected a near-sinusoidal current into the grid even under non-linear load conditions, ensuring power quality improvement while tolerating capacitor voltage imbalance. Furthermore, the adaptive switching strategy minimized losses by varying the switching frequency across voltage levels. Both simulation and 350 W prototype results verified the accuracy and practicality of the proposed system. The main merits of the proposed controlling method are: no need for expensive microprocessor; using logic gates, comparators, and analog devices; no halt and robust to noise and EMI; capability to balance the voltage of dc link capacitors; ability to produce output voltage levels even if the capacitors voltages are not balanced; modifies hysteresis band method that can enhance performance and decrease switching losses; reduction in harmonic contents; bidirectional power flow. These findings highlight the inverter’s potential as a cost-effective and scalable solution for smart grid applications and renewable energy integration, with future work directed toward exploring its full multifunctional capabilities. However, some aspects remain open for future investigation. The present study focuses on single-phase operation; extending the control strategy to three-phase systems and unbalanced grid conditions would be an important next step.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siddique, M. D. et al. A new multilevel inverter topology with reduce switch count. IEEE Access 7, 58584–58594 (2019).

Mohamad, A. S., Radzi, M. A. M., Mailah, N. F., & Othman, M. L. The Effects of Number of Conducting Switches in a Cascaded Multilevel Inverter Output (Universiti Putra Malaysia Institutional Repository (Universiti Putra Malaysia), 2019) https://doi.org/10.1109/icsgrc.2019.8837065.

Fang, X., Hu, H., Shen, Z. J. & Batarseh, I. Operation mode analysis and peak gain approximation of the LLC resonant converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27, 1985–1995 (2012).

Tian, Y., Wickramasinghe, H. R., Li, Z., Pou, J. & Konstantinou, G. Review, classification and loss comparison of modular multilevel converter submodules for HVDC Applications. Energies 15, 1985 (2022).

Ghat, M. B. & Shukla, A. A new H-bridge hybrid modular converter (HBHMC) for HVDC application: operating modes, control, and voltage balancing. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33, 6537–6554 (2018).

Gowaid, I. A., Adam, G. P., Massoud, A. M., Ahmed, S. & Williams, B. W. Hybrid and modular multilevel converter designs for Isolated HVDC–DC converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 6, 188–202 (2018).

Leon, J. I., Vazquez, S. & Franquelo, L. G. Multilevel converters: Control and modulation techniques for their operation and industrial applications. Proc. IEEE 105, 2066–2081 (2017).

Siddique, M. D., Iqbal, A., Sathik Mohamed Ali, J., Mekhilef, S. & Almakhles, D. J. Design and implementation of a new unity gain nine-level active neutral point clamped multilevel inverter topology. IET Power Electron. 13, 3204–3208 (2020).

Le, D. D., Hong, S. & Lee, D.-C. Fault detection and tolerant control for flying-capacitor modular multilevel converters feeding induction motor drives. J. Power Electron. 22, 947–958 (2022).

Garcia-Bediaga, A., Villar, I., Rujas, A. & Mir, L. DAB modulation schema with extended ZVS region for applications with wide input/output voltage. IET Power Electron 11, 2109–2116 (2018).

Xu, G., Sha, D., Xu, Y. & Liao, X. Hybrid-bridge-based DAB converter with voltage match control for wide voltage conversion gain application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33, 1378–1388 (2018).

Muhammad, T. et al. An adaptive hybrid control of reduced switch multilevel grid connected inverter for weak grid applications. IEEE Access 11, 28103–28118 (2023).

Freddy, T. K. S., Rahim, N. A., Hew, W.-P. & Che, H. S. Comparison and analysis of single-phase transformerless grid-connected PV inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 29, 5358–5369 (2014).

Sandeep, N., Ali, J. S. M., Yaragatti, U. R. & Vijayakumar, K. Switched-Capacitor-Based Three-Phase Five-Level Inverter Topology with Reduced Components. in 2018 8th IEEE India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE) 1–5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/iicpe.2018.8709481.

Faria, J., Fermeiro, J., Pombo, J., Calado, M. & Mariano, S. Proportional resonant current control and output-filter design optimization for grid-tied inverters using grey wolf optimizer. Energies 13, 1923 (2020).

Gadde, P. H. & Brahma, S. Comparison of PR and PI Controllers for Inverter Control in an Unbalanced Microgrid. in 2020 52nd North American Power Symposium (NAPS) 1–6 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1109/naps50074.2021.9449699.

Singh, J. K. & Behera, R. K. An improved hysteresis current controller for grid-connected inverter system to address power quality issues at reduced switching frequency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 57, 1892–1901 (2021).

Karamanakos, P., Liegmann, E., Geyer, T. & Kennel, R. Model predictive control of power electronic systems: methods, results, and challenges. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 1, 95–114 (2020).

Purraji, M., Zamiri, E., Sanchez, A. & de Castro, A. Rapid prototyping for design and test of FPGA-based model predictive controllers for power converters. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 20, 2419–2438 (2025).

Zheng, C., Dragicevic, T., Zhang, Z., Rodriguez, J. & Blaabjerg, F. Model predictive control of LC-filtered voltage source inverters with optimal switching sequence. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36, 3422–3436 (2021).

Chowdhury, M. R., Chowdhury, S., Rahman, M. A. & Islam, M. R. Advanced switching sequences based model-predictive control for single-phase NPC converters. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69, 3515–3526 (2021).

Shen, R. & Chung, H.S.-H. Mitigation of ground leakage current of single-phase PV inverter using hybrid pwm with soft voltage transition and nonlinear output inductor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36, 2932–2946 (2021).

Soomro, J. B. et al. Modified nearest level modulation for full-bridge based HVDC MMC in real-time hardware-in-loop setup. IEEE Access 9, 114998–115005 (2021).

Khan, S. A. et al. M-type and CD-type carrier based PWM methods and bat algorithm-based SHE and SHM for compact nine-level switched capacitor inverter. IEEE Access 9, 87731–87748 (2021).

Tariq, M. et al. Novel integrated NLC-SHE control applied in cascaded nine-level H-bridge multilevel inverter and its experimental validation. IEEE Access 11, 22209–22220 (2023).

Acuña, P. et al. A single-objective predictive control method for a multivariable single-phase three-level NPC converter-based active power filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 62, 4598–4607 (2015).

Valdez-Fernandez, A. A., Escobar, G., Campos-Delgado, D. U., Mtepele, K. O. & Martinez-Rodriguez, P. R. A model-based controller for a single-phase n-level CHB multilevel converter. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 125, 106454–106454 (2021).

Oliveira, G. et al. Single-phase shunt active power filter based on a 5-level converter topology. Energies 11, 1019–1019 (2018).

Wu, L. & Mingli, W. Single-phase cascaded H-bridge multi-level active power filter based on direct current control in AC electric railway application. IET Power Electronics 10, 637–645 (2017).

Sahli, A., Krim, F., Laib, A. & Talbi, B. Model predictive control for single phase active power filter using modified packed U-cell (MPUC5) converter. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 180, 106139–106139 (2020).

Komurcugil, H., Bayhan, S., Guler, N. & Blaabjerg, F. An effective model predictive control method with self-balanced capacitor voltages for single-phase three-level shunt active filters. IEEE Access 9, 103811–103821 (2021).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript. V. N., M. S., MB. B., and M. T.H. performed the data analysis and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nematzadeh Meinagh, V., Sabahi, M., Bannae Sharifian, M.B. et al. Multi-function multi-level grid tied inverter based on a new combined logic-analog controller with capacitors balancing ability. Sci Rep 16, 1795 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31420-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31420-4