Abstract

Central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring is valuable for guiding fluid management in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU. However, direct measurement via an intravenous catheter is invasive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive. Noninvasive ultrasound vessel measurements, such as internal jugular vein (IJV) and inferior vena cava (IVC) collapsibility index, offer alternatives but are affected by respiratory and anatomical factors. Static vessel diameters may provide a simpler, more reliable method, yet few studies have assessed their combined predictive value for estimating CVP. Critically ill, spontaneously breathing ICU patients received central venous pressure monitoring and ultrasound assessment of the transverse and anteroposterior diameter(TD and APD)of the IJV and CCA, along with IVC diameter (IVCD). The dataset was randomly divided into a training set and a validation set. Correlations between each vessel diameter and CVP were analyzed using linear regression. A multivariable linear regression model was then developed to predict CVP. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the ability of the model to identify patients with low CVP (< 8 mmHg). A total of 181 patients were enrolled. IJV-APD (r = 0.57), CCA-APD (r = 0.49), IVCD (r = 0.58) showed significant linear positive correlations with CVP. Using these correlative variables from univariate linear analysis, both IJV-APD (β = 1.789, p < 0.05) and ICVD (β = 1.334, p < 0.05) effectively predict the actual CVP values by multivariable linear regression. A predictive model combining IJV-APD and IVCD measurements accurately identified patients with CVP < 8 mmHg, with high AUC both in the training set (AUC = 0.807) and validating set (AUC = 0.749). We found that IJV-APD, CCA-APD and ICVD were associated with the level of CVP in critically ill patients. The predictive model incorporating IJV-APD and IVCD can effectively identify patients with low CVP (< 8 mmHg) in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critically ill patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) frequently experience significant and dynamic changes in hemodynamic status, necessitating continuous monitoring to guide treatment decisions and prevent organ dysfunction1,2. Central venous pressure (CVP) measurement, typically achieved by intravascular placement of the central venous catheter (CVC), has long been considered the cornerstone of hemodynamic monitoring3. As an indirect estimate of right atrial pressure and an indicator of cardiac preload and intravascular volume, CVP remains important to the management of conditions such as septic shock4, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)5, and cardiogenic shock6. Although the usefulness of CVP in predicting fluid responsiveness has been questioned, it continues to play a key role in guiding fluid resuscitation and vasopressor therapy, as reflected in current critical care guidelines7,8.

Invasive central venous pressure (CVP) measurement through CVC is often time-consuming, requires specialized monitoring equipment and trained personnel, and carries risks such as local hematoma, nerve injury, accidental arterial puncture, pneumothorax, infection, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and arrhythmia9. In addition, in some patients there is no way to obtain directly CVP monitoring through CVC operation, such as in the presence of coagulation abnormalities, skin infections at the puncture site, and the placement of a cardiac pacemaker10. Thus, there is an intense need for a non-invasive as well as a quick way to assess the systemic fluid volume status in critically ill patients. Advances in point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) have revolutionized bedside cardiovascular evaluation, enabling real-time assessment of vascular structures with minimal risk to the patient. Dynamic sonographic parameters, particularly the collapsibility indices (CI) of the inferior vena cava (IVC) or internal jugular vein (IJV), have been investigated as possible alternatives to CVP11. Although, these indices show moderate correlations with CVP, but their diagnostic performance is affected by respiratory dynamics, mechanical ventilation, intra-abdominal pressure, and operator variability12. Moreover, assessment of IVC variation may be limited in patients with obesity, intra-abdominal hypertension, or recent abdominal surgeries, limiting its universal applicability.

In this context, static vascular measurements, particularly vessel diameters, have received increasing attention as potentially simpler and more reproducible alternatives13,14,15. However, most studies have focused solely on the correlation between individual vessel diameters and central venous pressure (CVP), with few investigating the combined predictive value of multiple vessel diameters for CVP.

Based on this background, our study aimed to systematically investigate the correlation between the diameters of the IJV, CCA, and IVC measured by bedside ultrasound and CVP. We developed a predictive model using the important vessel diameters to reflect measured true CVP value. The ROC analysis demonstrated that the model reliably identified ICU patients with low CVP (< 8 mmHg). These findings highlight the association between pertinent vessel diameter parameters and directly measured central venous pressure (CVP) and the utility of incorporating vessel diameter measurements into noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring of critically ill patients.

Participants and methods

Studying participants

Critically ill patients admitted to the ICU of Anhui Chest Hospital from January 2024 to April 2025 were included in our study. Following informed consent obtained from their legal guardians, all patients underwent CVC placement for CVP monitoring. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) age > 18 years, (2) patients with preserved spontaneous breathing who were either not intubated or had been weaned from mechanical ventilation. Patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), significant pulmonary hypertension, or a history of neck surgery were excluded. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Anhui Chest Hospital (KJ2023-168).

Measurement method

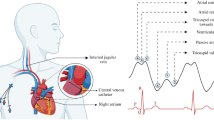

CVP monitoring

Following CVC insertion, the catheter tip position for each patient was confirmed by chest radiography or ultrasonography to ensure proper placement within or at the entrance of the right atrium. All patients were maintained in the supine position with the spine in a neutral alignment. To avoid measurement interference, all infusions through the central venous catheter were temporarily paused. Using Philips MX550 monitor, the pressure transducer was zeroed to atmospheric pressure and positioned at the level of the tricuspid valve (mid-axillary line at the fourth intercostal space). To ensure measurement precision, CVP values (expressed in mmHg) were collected at the conclusion of expiration directly from the screen display.

Ultrasound vessel measurement

Vascular ultrasound examinations were performed using a Philips portable ultrasound device (CX-50, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a 7.5 MHz linear array transducer. In accordance with previously established protocols, patients were placed in the supine position with the head in a neutral alignment. The probe was positioned at the level of the thyroid cartilage to obtain transverse images, from which the maximum transverse and anteroposterior diameters of the IJV and CCA were measured at end-expiration (recorded as IJV-TD, IJV-APD, CCA-TD, CCA-APD respectively)12. Subsequently, the probe was moved to the subxiphoid area to measure the maximum diameter of IVC in the longitudinal plane, also at end-expiration16. The ultrasound measurements of each vessel’s position and plane was illustrated as Fig. 2. All ultrasound examinations were independently performed by a single experienced critical care doctor with ultrasound qualification. Each measurement was repeated three times, and the average value was used for analysis. The sonographer was blinded to the each patients’ CVP results.

Vessel diameter via ultrasound detection. (A) IJV imaging in transverse plane (x: anteroposterior diameter, +: transverse diameter); (B) CCA imaging in transverse plane (x: anteroposterior diameter, +: transverse diameter); (C) ICV imaging in subxiphoid view (+: IVC diameter). IJV: internal jugular vein; IVC: inferior vena cava; CCA: common carotid artery.

Statistical analysis

All raw data were independently entered and cross-verified by two researchers using WPS Excel, then imported into R software (version R-4.4.1) for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and presented as medians with interquartile ranges (Q1–Q3). The total dataset was randomly split into a training set (70%) and a validation set (30%) using the “dplyr” R package, with a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility.

Using the training set, univariate linear regression models were constructed with the “lm” function to evaluate the association between each measured vascular diameter and CVP, with results visualized using the “ggplot2” R package. Variables with statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the univariate regression models were included in a multivariate linear regression model to develop the final regression model for CVP with multiple variables. The “car” R package was used to assess multicollinearity, model accuracy, and underlying assumptions, with results presented using Normal Q-Q plots, Scale-Location plots, Residual vs. Fitted plots, and Residual vs. Leverage plots.

Based on the multivariate linear regression results, variables with statistically significant associations with CVP (p < 0.05) were selected, and a CVP linear regression prediction equation was established according to the ordinary least squares(OLS) regression model formula (see Formula 1 below)17. The predicted CVP values were calculated using this equation, and the predictive performance for low CVP (< 8 mmHg) was validated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves on both the training and validation sets.

\(\:\widehat{{Y}_{i}}\) is the predicted value of the dependent variable for the \(\:i\)-th observation, \(\:\widehat{{\beta\:}_{0}}\) is the estimated intercept, \(\:\widehat{{\beta\:}_{1}}\cdots\:\widehat{{\beta\:}_{k}}\:\) are the estimated coefficients for the independent variables\(\:{X}_{1i\cdots\:}{X}_{ki}\). The model predicts \(\:{\:Y}_{i}\) based on \(\:k\) predictor variables across $ n $ observations.

Results

Baseline analyses

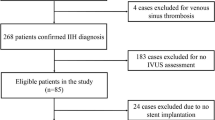

A total of 181 out of 192 enrolled patients were included in the final analysis, while 11 patients were excluded according to the predefined exclusion criteria, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The mean age of the cohort was 70 years (33–93), with 134 males and 47 females. The mean value of CVP was 6.42 mmHg, and a low state of CVP (< 8 mmHg) was observed in 155 patients (85.64%). Then total dataset was randomly divided into training set and validation set using R software, and the distribution of baseline variables between the two datasets was summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

The correlation of CVP between vessel diameters

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the association of CVP between each vessel diameter was examined. We could know that there was a significant positive correlation CVP and IVCD (r = 0.58, p < 0.05), while longitudinal measurements demonstrated significant linear correlations with both the IJV-APD (r = 0.57, p < 0.05) and CCA-APD (r = 0.49, p < 0.05); however, no statistically significant associations were found between CVP and transverse diameters of either IJV (IJV-TD: r = 0.09, p = 0.28) or CCA (CCA-TD: r = 0.09, p = 0.41). Our results suggested that IVCD, IJV-APD and CCA-APD may serve as reliable sonographic indicators of CVP status in critically ill patients, with IVCD demonstrating the strongest correlation, while transverse diameter of IJV and CCA measurements appear to have limited predictive value for CVP assessment.

Subsequently, multivariable linear regression models were constructed using these significant variables from univariate analysis. As shown in Table 2, both IJV-APD (β = 1.789, p < 0.05) and ICVD (β = 1.334, p < 0.05) effectively predicts the actual CVP values. Although CCA-APD showed a weak correlation with CVP in univariate analysis, it lost statistical significance (p = 0.856) after adjustment for other variables, suggesting limited independent predictive value. Therefore, CCA-APD was excluded from the final model to improve model simplicity and avoid collinearity. Regression diagnostic plots revealed that our regression model is robust, with assumptions of linearity, normality of residuals, and homoscedasticity being largely met (Fig. 4).

The predictive value of constructed model in high CVP patients

Subsequently, based on the derived polynomial model, we recalculated the predicted CVP values using the Formula 1: Predictive CVP value = β₀ + βIJV−APD × IJV-APD + βCVPD × CVPD. It has been shown that patients with low CVP (< 8 mmHg) are highly correlated with infusion responsiveness18, and with reference to other scholars’ studies on the subject19,20 we set the CVP threshold at 8 mmHg and categorized the patients into a high CVP group and a low CVP group. Subsequently, ROC analyses were used to assess the predictive value of the equation’s predictions for identifying low CVP (< 8 mmHg) patients in both the training and validation sets. In the training set, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.807; in the validation set, there was also a high AUC (0.749) as same (Fig. 5). These results demonstrated that the predictive model we constructed holds significant value and provides highly relevant reference for clinical practice, warranting attention from clinicians.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the relationship between central venous pressure (CVP) and ultrasound-derived measurements of internal jugular vein (IJV), inferior vena cava (IVC), and common carotid artery (CCA) diameters in critically ill patients. Our correlation analysis revealed that the anteroposterior diameters of the IJV (IJV-APD), IVC (IVCD), and CCA (CCA-APD) were significantly associated with CVP, consistent with previous findings21,22,23. For instance, Parenti et al. identified IJV-APD as the ultrasound parameter most strongly correlated with CVP in spontaneously breathing patients24, while Bayraktar and Kaçmaz reported a notable correlation between CCA diameter and CVP in mechanically ventilated patients25. These findings support the notion that static vascular measurements can serve as reliable indicators of central volume status. Unlike dynamic indices, such as the IVC collapsibility index, which are influenced by mechanical ventilation, intra-abdominal pressure, or patient cooperation14, our results, in line with Kumar et al.15, suggest that static vessel diameters offer a stable and reproducible method for estimating CVP.

Compared to dynamic indices like the IVC collapsibility index, which rely on consistent respiratory effort in spontaneously breathing patients or specific ventilator settings in mechanically ventilated ones, our model uses static measurements (IJV-APD and IVCD) that are less affected by respiratory variations. This characteristic may facilitate consistent CVP estimation in patients with variable breathing patterns or those who are uncooperative, where dynamic indices may be less reliable. Additionally, by incorporating both IJV and IVC measurements, the model captures complementary information from central and peripheral venous systems, potentially offering a more stable prediction than single-vessel approaches. Clinically, this model could serve as a practical bedside tool to support early identification of low CVP, particularly in settings where invasive monitoring is not immediately feasible, such as emergency departments or general wards. It may assist in guiding preliminary fluid management decisions for patients who do not yet require ICU admission, potentially reducing the need for invasive central venous catheterization in some cases. However, the model should be viewed as a supportive tool rather than a replacement for invasive CVP monitoring, as its primary value lies in aiding early hemodynamic assessment and optimizing initial fluid therapy, especially in spontaneously breathing or resource-limited settings.

We developed a predictive model to identify patients with a CVP below 8 mmHg, a threshold indicative of hypovolemia26,27. While CCA-APD has some extend correlation with CVP in univariate analysis, it is not statistically significant in multivariate analysis (p = 0.856) and is excluded from the final model to enhance simplicity and avoid collinearity. The resulting model, based on IJV-APD and IVCD, achieved AUC values of 0.807 and 0.749 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively, indicating moderate discriminatory ability. These values, while not reflecting perfect prediction, are comparable to those reported in prior ultrasound-based CVP studies. For instance, Sheher Bano et al. found that the internal jugular vein to common carotid artery diameter ratio reported only a modest discriminatory ability (AUC = 0.684) for predicting low CVP, yet it demonstrated good sensitivity and clinical usefulness in identifying patients requiring fluid resuscitation28, and a study in dialysis patients found AUCs of 0.79–0.86 for IVC indices in predicting high CVP19. These comparisons suggest that our model’s performance is reasonable, particularly when balancing noninvasiveness with clinical utility.

In addition, the development of a model that uses IJV-APD and IVCD to diagnose low CVP (< 8 mmHg), which is critical for timely fluid resuscitation in conditions like septic shock, where early intervention impacts outcomes29,30. The simplicity of measuring static vessel diameters, independent of respiratory phase or ventilatory mode, enhances its applicability across diverse clinical scenarios. The model’s noninvasive nature and ease of use make it a feasible option for repeated assessments during fluid resuscitation, providing real-time insights into fluid status.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other ICU populations or clinical settings. Second, ultrasound measurements were performed by operators, and despite standardized training and protocols, inter-operator variability could not be fully eliminated. Third, we included only spontaneously breathing patients without mechanical ventilation or continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), potentially limiting the model’s applicability to other critically ill subgroups. Finally, the cross-sectional design prevents evaluation of dynamic changes in vessel diameters over time or in response to fluid therapy. Future multicenter studies with larger sample sizes and blinded ultrasound assessments are needed to validate and expand our findings.

In conclusion, ultrasound measurements of IJV-APD and IVCD demonstrated a significant correlation with CVP levels. The predictive model based on these variables offers a practical approach to identifying patients with low CVP who may benefit from early fluid challenge, particularly in settings where invasive monitoring is not immediately available.

Data availability

If reasonably requested by the corresponding author, we will share the data on which this article is based.

References

De Backer, D. et al. How can assessing hemodynamics help to assess volume status? Intensive Care Med. 48 (10), 1482–1494 (2022).

Brunker, L. B. et al. Elderly patients and management in intensive care units (ICU): clinical challenges. Clin. Interv Aging. 18, 93–112 (2023).

De Backer, D. & Vincent, J. L. Should we measure the central venous pressure to guide fluid management? Ten answers to 10 questions. Crit. Care. 22 (1), 43 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Central venous pressure measurement is associated with improved outcomes in septic patients: an analysis of the MIMIC-III database. Crit. Care. 24 (1), 433 (2020).

Tang, R., Peng, J. & Wang, D. Central venous pressure measurement is associated with improved outcomes in patients with or at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome: an analysis of the medical information Mart for intensive care IV database. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 858838 (2022).

Schiefenhovel, F. et al. High central venous pressure after cardiac surgery might depict hemodynamic deterioration associated with increased morbidity and mortality. J. Clin. Med. 10, 17 (2021).

Tong, X. et al. Association between central venous pressure measurement and outcomes in critically ill patients with severe coma. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28 (1), 35 (2023).

Marik, P. E. & Cavallazzi, R. Does the central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? An updated meta-analysis and a plea for some common sense. Crit. Care Med. 41 (7), 1774–1781 (2013).

Teja, B. et al. Complication rates of central venous catheters: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 184 (5), 474–482 (2024).

Akmal, A. H., Hasan, M. & Mariam, A. The incidence of complications of central venous catheters at an intensive care unit. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2 (2), 61–63 (2007).

Jassim, H. M. et al. IJV collapsibility index vs IVC collapsibility index by point of care ultrasound for Estimation of CVP: a comparative study with direct Estimation of CVP. Open. Access. Emerg. Med. 11, 65–75 (2019).

Prekker, M. E. et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to estimate central venous pressure: a comparison of three techniques. Crit. Care Med. 41 (3), 833–841 (2013).

Donahue, S. P. et al. Correlation of sonographic measurements of the internal jugular vein with central venous pressure. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 27 (7), 851–855 (2009).

Ciozda, W. et al. The efficacy of sonographic measurement of inferior Vena Cava diameter as an estimate of central venous pressure. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 14 (1), 33 (2016).

Kumar, A. et al. Correlation of internal jugular vein and inferior Vena Cava collapsibility index with direct central venous pressure measurement in Critically-ill patients: an observational study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 28 (6), 595–600 (2024).

Chaves, R. C. F. et al. Assessment of fluid responsiveness using pulse pressure variation, stroke volume variation, plethysmographic variability index, central venous pressure, and inferior Vena Cava variation in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 28 (1), 289 (2024).

Mahanty, C., Kumar, R. & Mishra, B. K. Analyses the effects of COVID-19 outbreak on human sexual behaviour using ordinary least-squares based multivariate logistic regression. Qual. Quant. 55 (4), 1239–1259 (2021).

Bentzer, P. et al. Will this hemodynamically unstable patient respond to a bolus of intravenous fluids? JAMA 316 (12), 1298–1309 (2016).

Sekiguchi, H. et al. Central venous pressure and ultrasonographic measurement correlation and their associations with intradialytic adverse events in hospitalized patients: A prospective observational study. J. Crit. Care. 44, 168–174 (2018).

Xu, H. P. et al. Prognostic value of hemodynamic indices in patients with sepsis after fluid resuscitation. World J. Clin. Cases. 9 (13), 3008–3013 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Ultrasonographic measurement of the respiratory variation in the inferior Vena Cava diameter is predictive of fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 40 (5), 845–853 (2014).

Hilbert, T. et al. Common carotid artery diameter responds to intravenous volume expansion: an ultrasound observation. Springerplus 5 (1), 853 (2016).

Ilyas, A. et al. Correlation of IVC Diameter and Collapsibility Index With Central Venous Pressure in the Assessment of Intravascular Volume in Critically Ill Patients. Cureus 9(2), e1025 (2017).

Parenti, N. et al. Ultrasound imaging and central venous pressure in spontaneously breathing patients: a comparison of ultrasound-based measures of internal jugular vein and inferior Vena Cava. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 54 (2), 150–155 (2022).

Bayraktar, M. & Kacmaz, M. Correlation of internal jugular vein, common carotid artery, femoral artery and femoral vein diameters with central venous pressure. Med. (Baltim). 101(43), e31207 (2022).

Eskesen, T. G., Wetterslev, M. & Perner, A. Systematic review including re-analyses of 1148 individual data sets of central venous pressure as a predictor of fluid responsiveness. Intensive Care Med. 42 (3), 324–332 (2016).

Song, X. et al. Exploring the optimal range of central venous pressure in sepsis and septic shock patients: A retrospective study in 208 hospitals. Am. J. Med. Sci. 368 (4), 332–340 (2024).

Bano, S. et al. Measurement of internal jugular vein and common carotid artery diameter ratio by ultrasound to estimate central venous pressure. Cureus 10 (3), e2277 (2018).

Font, M. D., Thyagarajan, B. & Khanna, A. K. Sepsis and septic Shock - Basics of diagnosis, pathophysiology and clinical decision making. Med. Clin. North. Am. 104 (4), 573–585 (2020).

Choi, S. J. et al. Elevated central venous pressure is associated with increased mortality in pediatric septic shock patients. BMC Pediatr. 18 (1), 58 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Haobo Kong, Ye Li and Yanbei Zhang. Acquisition of data: Zhengzhong Zhang and Depei Shen. Drafting of manuscript: Haobo Kong, Zhengzhong Zhang and Depei Shen. All authors modified and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Anhui Chest Hospital (KJ2023-168). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from individual or guardian participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, H., Zhang, Z., Shen, D. et al. Predictive value of internal jugular vein combining with inferior vena cava diameters by ultrasound in central venous pressure of ICU patients. Sci Rep 16, 2138 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31945-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31945-8