Abstract

The mechanical characterization of block-in-matrix rocks (bimrocks) remains a significant challenge in geotechnical engineering, primarily due to the difficulty of obtaining undisturbed specimens. While the Volumetric Block Proportion (VBP) is a recognized controlling factor, the specific role of block orientation is not well quantified. This study employs a systematic experimental approach, augmented by Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), to investigate the effect of block orientation angle relative to loading direction (α) on the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), deformation, and failure mechanisms of bimrock. A total of 87 synthetic specimens with VBP from 0% to 50% and α from 0° to 90° were tested. Statistical analyses confirm that both VBP and α, as well as their interaction, are statistically significant for both UCS and Elastic modulus. An increase in VBP reduces UCS, though this effect reduces with increasing α. Failure analysis reveals that higher VBP increases crack density, while an increase in α from 0˚ to 90˚ forces failure paths to become more tortuous. The Elastic modulus increases with VBP, with the most pronounced stiffening effect at α = 0° (vertical alignment). This effect diminishes with an increase in α and approaches that of the pure soil for α = 90°. In contrast, Poisson’s ratio showed no systematic trend, underscoring its sensitivity to local heterogeneity of Bimrock. This research conclusively demonstrates that block orientation is a critical, independent governing parameter. Consequently, predictive models must account for the interaction between block proportion and orientation to accurately simulate bimrock behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The properties of mélanges have been a subject of debate among geologists since Greenly1 first identified their autoclastic composition. These geological formations are widespread, having been documented in over 70 countries, particularly in mountainous regions2,3. To direct the focus of engineers toward the mechanical behaviour of these mixtures for design and construction, Medley4 introduced the term “bimrock” (block-in-matrix rock). He defined it as “a mixture of geotechnically significant blocks within a finer-grained matrix,” where “geotechnically significant” denotes the mechanical contrast between the blocks and the surrounding matrix4,5.

Technological advancement has driven a surge in demand for both surface and subsurface construction projects, including tunnels, dams, roads, and buildings. Given the global prevalence of bimrocks, many of these projects are likely to encounter such complex geological conditions. A review of previous studies indicates that civil structures in bimrocks, especially tunnels and slopes, can exhibit a higher factor of safety and improved stability6,7,8. However, experimental studies have reported contradictory findings, highlighting a discrepancy in the current understanding9,10.

Conventional design practice in bimrocks often simplifies the mass by ignoring the blocks and generalizing the matrix properties. This simplification, however, can lead to significant technical problems and serious consequences during construction7,11. Compounding this design challenge is the difficulty in preparing intact laboratory specimens. The significant strength contrast between blocks and matrix causes harder blocks to intrude into the weaker matrix during coring, resulting in severe specimen disturbance or even total destruction12. Consequently, preparing representative specimens for laboratory testing is often, if not always, impractical.

While in-situ experiments, such as the direct shear tests conducted by Coli et al.13,14, can provide invaluable insights into the mechanical behaviour of bimrocks, their utility is often limited. The prohibitive cost and considerable technical challenges of these tests typically restrict their application to a small number of locations, raising concerns about how well the results represent the spatial variability of the entire geotechnical sector.

Recent advances in numerical modelling, particularly using the Discrete Element Method (DEM) and the hybrid Finite-Discrete Element Method (FDEM), offer promising avenues for studying bimrock behaviour15,16,17,18,19. Recently, Li et al.20 investigated the post-peak behaviour of bimrock under uniaxial compression using combined computed tomography and DEM and found that damping coefficient and loading rate are crucial parameters on post-peak behaviour. A primary challenge in these techniques, however, is the accurate determination of block-matrix interface properties, which requires further experimental validation. Consequently, controlled experimental studies on synthetic bimrocks have emerged as a vital remedial approach to elucidate the fundamental mechanical properties of these complex materials.

Experimental studies have been helpful in elucidating the mechanical behaviour of bimrocks. Among various factors, the Volumetric Block Proportion (VBP) has been identified as a primary controlling parameter, with its influence most pronounced within a critical range of 25% to 75%, where the composite material exhibits a distinct mechanical response different from its individual components5,21. The relationship between VBP and strength, however, is complex and appears to be context-dependent. For instance, while Sonmez et al.22,23 observed an increase in Unconfined Compressive Strength (UCS) with an increase in VBP in welded agglomerates, a more common trend for unwelded bimrocks is a negative correlation. This decrease in UCS with increasing VBP has been consistently demonstrated in studies on fault breccias24, synthetic specimens22,25,26, and natural bimrock samples27. Similarly, direct shear tests have shown that shear strength generally declines with higher VBP, a trend noted to vary between critical thresholds of 40% and 60%28. Beyond VBP, other geometric factors significantly influence mechanical properties. Previous studies have shown that block size and distribution play a crucial role; increases in block size at a constant VBP can lead to a higher internal friction angle but a reduction in cohesion and peak shear strength29,30. Furthermore, scale effect is important, with studies indicating a decrease in frictional strength in larger specimens31, and investigations into complex bimrocks with multiple matrices have provided insights into failure mechanisms32.

Bimrocks form through various geological processes, tectonic, sedimentary, and mass-wasting, each imparting a distinct fabric that can influence block orientation. In tectonic settings such as subduction or fault zones, intense shear deformation can rotate and align blocks parallel to the developing shear plane2,33. In sedimentary environments like olistostromes or debris flows, the orientation of blocks is influenced by the flow dynamics and depositional processes. Similarly, in terrestrial mass-wasting events such as landslides, gravitational forces can align blocks parallel to the slope or direction of movement34,35. In metamorphic bimrocks, directed pressure during metamorphism may align blocks parallel to the foliation or schistosity of the matrix36. A representative example of such structurally controlled bimrock is found at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1). This area is underlain by the Silurian Maoxian Group, a metamorphic complex composed of grey carbonaceous phyllite (or slate) and green sericite phyllite interlayered with banded meta-sandstone and argillaceous limestone. The phyllite exhibits a well-developed, mechanically weak foliation. Weathering of this foliated rock mass generates predominantly flat, platy phyllite blocks. During accumulation on hillslopes, these flat blocks have developed a distinct imbricate texture, a specific type of block orientation where particles oriented in a preferred direction, often influenced by gravity and depositional processes37, as shown in Fig. 1(c).

Phyllite rocks (a) the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (b) the structure of phyllite rocks, which consists of phyllite blocks and matrix masses (c) A schematic view of the orientated blocks37.

A growing body of evidence suggests that block orientation can significantly alter the mechanical properties of bimrocks38. However, researches dedicated to this topic remains limited. Lindquist39 in a pioneering experimental study using triaxial compression tests, found that the orientation angle (α), defined as the angle between the block orientation and the major principal stress direction, significantly influences strength and deformation. Specimens with α = 30° exhibited the lowest cohesion, while the elastic modulus was highest for vertically aligned blocks (α = 0°) and lowest for horizontal ones (α = 90°). Complementing this, Jiang et al.40 used numerical simulations (PFC2D) to show that cohesion and internal friction angle at α = 0° were slightly greater than at α = 90°. Li et al.41 investigated the effect of block shape on the stress-strain curve under uniaxial compression and direct shear tests results for bimrocks with 30% and 60% VBPs. They found that at 30% VBP, the correlation between UCS and shape factor is chaotic, whereas at 60% VBP, The UCS increased with an increase in shape factor. Beyond mechanical properties, Wan et al.37, demonstrated through permeability tests that block orientation also affects fluid flow, with macroscopic permeability increasing as the orientation shifts to 90°.

While these studies confirm the significance of block orientation, a comprehensive understanding of its impact on mechanical behaviour is still lacking. The interaction between block orientation and VBP is particularly underexplored. This gap in the literature necessitates further systematic investigation.

This study aims to experimentally investigate the effect of block orientation on the strength, deformation, and failure mechanisms of synthetic bimrock under uniaxial compression. A comprehensive testing program was designed, manufacturing laboratory specimens with four different VBPs of 12.5%, 25%, 37.5%, and 50%. For each VBP, the block orientation was varied from 0° to 90° at 15° intervals. To account for the inherent heterogeneity arising from the stochastic block arrangement, three replicates were prepared for each unique combination of VBP and orientation, resulting in a total of 87 specimens. All specimens were tested under uniaxial compression using an MTS machine, and the results were analysed to elucidate how block orientation governs mechanical behaviour across a range of VBPs.

Sample Preparation

Synthetic specimens were fabricated in three stages: block design, matrix design, and specimen fabrication. The first stage involved defining the geometry (shape, size, and distribution) and quantity of blocks for each target VBP. Subsequently, a matrix material was selected to meet the required mechanical contrast with the blocks. In the final stage, cylindrical specimens were manufactured according to UCS testing standards, varying both the VBP and the orientation of the blocks within the matrix.

Design of blocks

In nature, blocks within bimrocks exhibit a variety of shapes, including spherical, prismatic, ellipsoidal, and irregular forms. For this study, blocks were modelled as ellipsoids to investigate the effect of block orientation on mechanical behaviour. This shape was selected because naturally oriented blocks are commonly ellipsoidal or oval. The ellipsoid axes were assigned a size ratio of 1:1.6, a value frequently observed in nature and known as the golden ratio42.

The block size was determined based on established thresholds for bimrocks. Following the observations of Medley and Goodman43 on the Franciscan complex, the lower and upper dimensional thresholds for a block are 5% and 75% of the relevant engineering dimension, respectively. For the laboratory studies, the specimen diameter is taken as the engineering dimension21, yielding a theoretical block long-axis (db) range of 7–105 mm in this study. Accordingly, four block sizes of 40, 60, 80, and 100 mm were selected for experimentation.

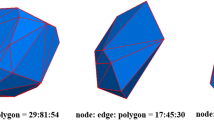

The number of blocks for each size was designed to follow a fractal distribution, consistent with observations of the Franciscan mélange21, illustrated in Fig. 2(a). The relationship between block frequency and size was approximated by a negative power law6,44, as illustrated in the logarithmic plot of frequency versus dimensionless block size in Fig. 2(b). For each target VBP, the number of blocks was calculated to satisfy this distribution criterion.

Selection of the block size based on: (a) Fractal distribution of blocks with sizes of 40, 60, 80 and 100 mm in bimrock and comparison with Franciscan melange21 and (b) Examining the negative power law for block size distribution in specimens.

Based on the size distribution, the required number of blocks was calculated, leading to the production of 3,444, 777, 273, and 63 blocks with long axes of 40, 60, 80, and 100 mm, respectively. Custom casting molds were manufactured for these specific dimensions (Fig. 3). The blocks were produced from a mixture of 40% plaster, 20% cement, and 40% water by weight, adopting the composition used by Khorasani et al.42. Blocks were remained in their sealed molds for 24 h after casting. They were then demolded and cured for 28 days in a controlled climate chamber with a constant temperature (20 ˚C ± 2 °C) and humidity (relative humidity of 40% ± 5%) to reach their final strength. They were placed on level shelves with periodical environmental exposure before curing in bimrock specimens.

Matrix design

Bimrocks are fundamentally characterized by a pronounced mechanical contrast between the blocks and the surrounding matrix. Adopting the contrast criteria proposed by Medley and Zekkos5 and Kalender et al.9, this study ensured contrast ratios of greater than 2 for the elastic modulus (E), 1.5 for the UCS, and 1.5–2.5 for the friction coefficient (\(\:\text{tan}\phi\:\)). To meet these criteria, various matrix compositions were trialed and their mechanical properties evaluated through a series of laboratory tests, including uniaxial compression, triaxial compression, and indirect tensile (Brazilian) tests, conducted in accordance with ISRM45 and ASTM46,47 standards. A mixture of 40% stone powder, 20% gypsum, and 40% water by weight was ultimately selected as the matrix. The resulting stress-strain curves for the chosen matrix and block materials are compared in Fig. 4, and their corresponding mechanical properties are summarized in Table 1.

The strength contrasts between the block and matrix were evaluated against established criteria5,9. As summarized in Table 2, the results confirm that the synthetic specimen meets all requirements for a bimrock.

Preparation of Bimrock specimens

Studying the effect of block orientation required the precise placement of blocks at predetermined angles within the matrix. To achieve this, a line was drawn along the elongation axis of each block to define its orientation relative to the specimen axis. The blocks were cast in transparent Plexiglass molds (140 mm internal diameter, 280 mm height), which permitted visual verification of their alignment during placement. A schematic of this alignment procedure is provided in Fig. 5. The total volume of matrix and blocks for each specimen was not poured all at once. After preparing the required amount of matrix for each VBP, the casting was divided by pouring the matrix into several layers (See Fig. 5). In each layer, the pre-measured portion of blocks for that layer was manually scattered and embedded into the matrix with pre-defined orientation. Due to short period of casting for the designed matrix, no considerable block settlement was observed in specimens. To verify the accuracy of block orientations after casting, selected specimens were sectioned along their vertical axis. The orientations of the exposed blocks were measured, as shown in Fig. 6. These measurements revealed a maximum orientation error of less than 2.5°, confirming the success of the casting procedure in achieving the intended block arrangements.

A total of 84 synthetic specimens were prepared with block orientation angles (α) of 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 degrees and VBP of 12.5%, 25%, 37.5%, and 50%. Although the lower strength threshold is often cited at VBP of 20–25%, this value can be influenced by block orientation. By including a value below this typical threshold (12.5%) and comparing it directly to the pure matrix, we can precisely quantify the onset of block influence across different orientation angles which allowed us to map the gradient of property change, providing a complete picture of how mechanical behaviour evolves with increasing block content. It should be noted that preparing specimens with VBPs exceeding 50% was not practically feasible due to associated difficulties for placement of blocks within the designed mold, especially at high orientation angles. Each unique combination of angle and VBP was replicated three times. Additionally, three pure matrix specimens (VBP = 0%) were cast as a pure matrix condition. After demolding at 24 h, all specimens were cured for 28 days under constant laboratory temperature (20 °C ± 2 °C) and humidity (relative humidity of 40% ± 5%) in a controlled climate chamber to dry naturally and achieve final strength48,49. Following the curing period, specimens were oven-dried to remove free water and ensure uniform testing conditions, at a constant 55 °C for 24 h immediately prior to testing. The recommended temperature in previous studied on gypsum-based materials is less than 60 ˚C50,51. A temperature of 55 °C was found sufficiently high to effectively evaporate free pore water over a reasonable timeframe but is low enough to prevent the dehydration of gypsum48.

Experimental tests set-up

Uniaxial compression tests were conducted using an MTS 815 servo-controlled testing system. The servo-controlled mechanism allowed for the complete capture of the stress-strain response, including the post-peak behaviour. A constant displacement rate of 0.2 mm/min was applied until the specimens reached their residual state. The axial load was measured with a load cell (accuracy: 0.1 kN) located beneath the specimen. Axial strain was measured directly using an axial extensometer mounted on the specimen’s vertical axis to eliminate the influence of platen-contact effects, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Lateral strain was recorded using a circumferential extensometer. All data were recorded during the loading stage for subsequent analysis to determine the mechanical properties.

Results and discussion

Results of uniaxial compression tests

Uniaxial compression tests were conducted to evaluate the mechanical behaviour of specimens with varying block orientations and VBP. The resulting stress-strain curves, illustrated in Fig. 8, for orientation angles from 0° to 90° at various VBPs, demonstrate that block orientation significantly alters the strength and deformation characteristics of bimrock. The UCS was defined as the peak axial stress. The elastic modulus was determined from the slope of the linear portion of the axial stress-strain curve, while Poisson’s ratio was calculated as the negative ratio of the slopes of the lateral and axial stress-strain curves in elastic deformation stage. The results indicate that the lowest strength occurred that at block orientation of 0°, while the highest strength was observed at 90°, across all VBPs. This confirms that the rock blocks aligned with the loading direction can induce strength reduction, even at low VBPs. However, this strength reduction diminishes as the block orientation increases to 90°, particularly at lower VBPs. Furthermore, an increase in VBP leads to more pronounced strength anisotropy, as evidenced by a greater disparity in strength between different orientations. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying this strength anisotropy, a detailed analysis of the failure modes is presented in the following section. Axial and lateral displacements were measured using extensometers. The onset of nonlinear behaviour in the stress-strain curves is attributed to the initiation and propagation of cracks. A detailed analysis of the stress-strain curves, accounting for the specific random block arrangements at each VBP and orientation, is provided in the subsequent sections to unravel the underlying deformation mechanisms.

Failure mechanism in Bimrock specimens

The failure mode of a specimen is a critical characteristic that reflects the internal stress distribution and the influence of test conditions on rock deformation and fracturing pross52,53,54. In uniaxial compression test, failure is the consequence of micro-fracturing, involving the nucleation of cracks at stress concentration points and their propagating along the direction of maximum principal stress. This can result in tension, shear or coupled tension and shear failure modes due to localised stress concentrations around microscopic cracks, with the specific mechanism dictated by the orientation of cracks and the corresponding stress distribution55.

In the specific case of bimrocks, the block-matrix interface acts as a primary weakness zone. The location, orientation, and density of these interfaces fundamentally dictate the failure mechanism, often leading to complex fracture patterns56 that differ from those of intact rock. This is consistent with established failure mode classifications for rock materials under uniaxial compression, such as the five distinct modes identified by Szwedzicki55: simple tension, multiple tension, multiple fracturing, simple shear, and multiple shear. The simple tensile mode is less common and typically occurs in the absence of significant pre-existing micro-cracks. Multiple tensile fracturing, characterized by failure along numerous planes, often involves the release of a large amount of energy, with fractures typically being vertical and parallel to the loading direction. In contrast, predominant shear failure results in disintegration along inclined planes that often forming a cone-like structure. The simple shear features a single shear plane developing across the unconfined portion of the specimen; the associated strength is often lower than in other modes, as failure typically localizes along a pre-existing weak vein. Finally, the multiple shear mode is defined by the development of two or more non-parallel, oblique shear planes.

The failure surfaces observed in the bimrock specimens of this study (Fig. 9) clearly demonstrate the governing role of the block-matrix interface. In pure matrix specimens (VBP = 0%), failure occurred through multiple tensile cracks aligned with the loading direction. The inclusion of blocks, however, significantly altered the failure path, with fractures consistently propagating along the block-matrix interfaces. This confirms that these boundaries represent the weakest planes, controlling both crack initiation and propagation, and thereby accelerating failure under load. A critical observation is that, no fracture penetrated the blocks themselves, underscoring the importance of their higher strength relative to the matrix. This is consistent with the high strength contrast ratio of approximately six in this study, a condition known to divert fractures around blocks rather than through them27,57.

Analysis of the failure surfaces reveals three key mechanisms: tortuous fracture paths, preferential propagation along block-matrix boundaries, and significant matrix failure induced by block rotation. Consequently, the orientation of blocks exerts a primary control on the failure surface geometry, with Fig. 9 demonstrating that the location and orientation of larger blocks, in particular, can dictate the macroscopic direction of the failure surface. The smaller blocks from the fractal distribution create a higher density of block-matrix interfaces, which promotes more distributed micro-cracking and increases energy dissipation. Simultaneously, the presence of larger blocks acts as more significant obstacles, forcing the main crack to deflect around them, thereby increasing the tortuosity and complexity of the failure path. This interaction between the fine and coarse fractions of the fractal distribution creates a synergistic effect that is fundamentally different from a uniform size distribution, leading to the more complex and branched crack patterns was observed, particularly at high VBP contents. Characterizing the internal failure patterns from the specimen periphery was challenging, as techniques like X-ray micro-computed tomography for internal damage characterization58,59,60,61 were not available in this study. Therefore, failure surfaces were inferred from surface crack patterns and visual inspection of the specimen exteriors, as summarized in Fig. 10.

The fracture surfaces resulted from tensile, shear, or a combination of both crack types. Tensile cracks propagate parallel to the loading direction along block-matrix interfaces, whereas shear cracks develop along inclined interfaces. With an increase in both VBP and the orientation angle, a greater proportion of shear cracks was observed. This transition is evident in Fig. 11, which depicts failed specimens at the VBP of 12.5%. At low orientation angles (0° − 30°), large-scale fractures were primarily aligned with the loading direction. At higher angles, the failure surface instead followed the orientation of the block’s long axis. This demonstrates that block orientation is the primary control on the failure path, with the mechanism transitioning from tensile-dominated to shear- or mixed-mode as α increases from 0° to 90°. Despite this transition, tensile cracking remained a decisive and observable component at all orientations.

To quantitively analyse crack propagation, crack density was quantified as the crack total length per unit area for each combination of VBP and block orientation. The results, presented in Fig. 12, demonstrate a clear correlation between both material parameters and the crack density. Specifically, crack density increases with both higher VBP contents and greater block orientation angles. While the increase from 12.5% to 25% VBP is modest, a significant intensification of this trend is observed at higher VBP levels. At a block orientation of 0°, cracks primarily propagate along the loading direction. The increase in crack density at higher VBPs is attributed to the greater number of block-matrix interfaces, which act as initiation, promoting more distributed microcracking. When the block orientation increases to 90°, the alignment of blocks with the loading direction facilitates the generation of multiple cracks at the block-matrix interfaces. These cracks subsequently propagate through the matrix to form the final failure surface, resulting in a higher overall crack density. This effect is amplified at elevated VBP contents, where the increased number of interfaces further multiplies the crack initiation points.

Effect of VBP and block orientation on the UCS

The relationship between VBP and UCS at various orientation angles is shown in Fig. 13. The results indicate a consistent decrease in UCS with an increase in VBP. This trend is attributed to the block-matrix interface, which acts as the weakest plane in unwelded bimrock. A higher VBP increases the total area of these interfaces, facilitating crack initiation and coalescence at lower stress levels and thereby reducing the overall strength16. Notably, the rate of strength reduction is more pronounced at a block orientation angle of 0° than at 90°. This occurs because the matrix itself tends to fail through vertical oriented tensile cracks under uniaxial compression (Fig. 9 (d)). At 0°, the long axis of block-matrix interfaces is aligned vertically, parallel to loading direction. The alignment the inherent weakness zone along the loading direction creates a preferential path for crack initiation and propagation.

The influence of block orientation on the UCS at constant VBP is presented in Fig. 14. The results demonstrate a consistent increase in UCS as the block orientation angle rises from 0° to 90°. This strengthening effect occurs because horizontally oriented blocks (90°) force the failure surface to deviate around them, creating a more complex and tortuous fracture path. This mechanism results in a strength increase that approaches that of the pure matrix. The most pronounced effect of orientation on UCS is observed at the VBP of 50%, underscoring the dominant role of block-matrix interfaces in governing the failure mechanism of bimrocks.

Effect of VBP and block orientation on the deformation characteristics of Bimrock

The influence of VBP on the elastic modulus at various block orientations is presented in Fig. 15. The elastic modulus increases with an increase in VBP, which is attributed to the higher volumetric content of stiffer blocks within the softer matrix, resulting in reduced axial strain under load. This stiffening effect is most pronounced at a block orientation of 0°, a finding consistent with the triaxial test results of Lindquist39 due to alignment of blocks along the loading direction. Furthermore, the influence of block orientation on the elastic modulus becomes negligible at angles greater than 45°.

The effect of block orientation on the elastic modulus at constant VBPs is illustrated in Fig. 16. At low VBPs (12.5% and 25%), block orientation has no considerable effect on the elastic modulus, indicating that the matrix dominates the axial deformation due to limited block participation in axial deformation. At high VBPs, however, the elastic modulus becomes highly anisotropic, varying significantly with the block orientation relative to the loading direction. The modulus is highest when the blocks are aligned parallel to the load (α = 0°) and lowest when perpendicular (α = 90°). This anisotropy occurs because at α = 0°, the stiffer blocks are optimally aligned to carry the load, resulting in lower axial strain and a higher modulus. Conversely, at α = 90°, load transfer is governed primarily by the weaker matrix, leading to a lower overall elastic modulus.

The influence of VBP and block orientation on Poisson’s ratio is presented in Fig. 17. The results show that an increase in VBP leads to inconsistent results in the measured values of the Poisson’s ratio. This inconsistency is attributed to the inherent heterogeneity of bimrocks, where lateral strain is highly sensitive to the specific spatial arrangement of blocks. This variability poses a persistent challenge in obtaining statistically significant results for Poisson’s ratio, a difficulty consistently noted in previous both physical and numerical experiments.

A quantitative analysis of trends and dispersion was performed by calculating the mean and coefficient of variation (COV) for all tested conditions and the results are presented in Fig. 18. The results reveal a fundamental difference. The UCS and Elastic modulus are systematically influenced by VBP and block orientation, while no considerable trend can be observed for Poisson’s ratio. The results provide quantitative evidence that Poisson’s ratio is not only more variable but also fundamentally less predictable in bimrocks. The COV values for all three parameters also fluctuate significantly, providing quantitative evidence that the mechanical response of bimrocks is highly sensitive to the specific configuration of heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis of the results using response surface methodology and ANALYSIS of variance

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a multivariate statistical approach employed to model and analyse the relationship between multiple independent input variables (factors) and output responses. It is used to empirically model the relationship between several independent variables (factors) and one or more dependent responses, often with the goal of optimizing a process with a minimal number of experiments62,63,64. In this study, independent variables include VBP and the block orientation while the responses are UCS and Elastic modulus. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed to quantify the relative influence of individual parameters on the responses. The procedure calculates the sum of squares (\(\:{SS}_{i}\)) and degrees of freedom (vi) for each factor to determine its mean square (\(\:{MS}_{i}\)), are defined as:

where np is the total number of experiments, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the response value for the ith experiment and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the overall mean across all experiments. For a given factor j, nj represents its number of levels, \(\:{y}_{i\left|k\right.}\) denotes the subset responses where factor j is set to level k and \(\:{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{k}\) is the mean of that subset. The error sum of squares (SSₑ) and error mean square (\(\:{MS}_{e})\) are given as:

where \(\:{n}_{f\:}\)denotes the number of factors. The F-value for each factor (\(\:{F}_{j}\)), is calculated as the ratio of the factor mean square to the error mean square, is used to assess statistical significance.

Specifically, the calculated F-value for each factor was compared against critical values from the F-distribution at a specified confidence level to determine its significance on the response. The associated degrees of freedom for total mean square \(\:{v}_{t}\) and error mean square \(\:{v}_{e}\) are determined as656667:

The ANOVA results for the UCS are presented in Table 3. The model F-value of 113.58 implies the model is highly significant, with less than a 0.01% probability that it could occur due to noise. Model terms with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Accordingly, the VBP, block orientation, and their interaction were found to have a significant effect on the UCS. The non-significant lack of fit (p = 0.9711) validates the model’s adequacy in representing the experimental data.

The suggested two-factor interaction model needs to be assessed based on the distribution of residuals as well as prediction assessment methods68. Results of statistical analyses for the significance of the model are presented in Fig. 19, which show that the data are normally distributed and there is also a good correlation between predicted and measured UCS.

Figures 20 and 21 illustrate the effects of the individual parameters and their interaction on the normalized UCS. The UCS values are normalized against the VBP = 0 (pure matrix) condition to highlight relative strength changes. The results indicate that the increase in VBP significantly reduces the bimrock strength, whereas increasing the block orientation from 0° (vertical) to 90° (horizontal) reduce this reduction rate. The interaction plot reveals that the influence of block orientation is negligible at low VBPs but becomes pronounced at higher VBPs. Simultaneously, the sensitivity of UCS to changes in VBP decreases with increasing block orientation angle.

Table 4 summarizes the ANOVA results evaluating the effects of VBP and block orientation angle on the normalized Elastic Modulus. The model’s high significance is indicated by an F-value of 21.99 (p < 0.0001). Both VBP and block orientation angle, as well as their interaction, were identified as statistically significant terms (p < 0.05). The model’s validity is further supported by a non-significant lack of fit. The suggested two-factor interaction model was assessed based on the distribution of residuals and prediction assessment methods and results are presented in Fig. 22. It can be observed that data are normally distributed with no skewness and bias and there is also a good correlation between predicted and measured for Elastic modulus of bimrocks.

The effects of VBP, block orientation angle, and their interaction on the normalized Elastic Modulus are depicted in Figs. 23 and 24. The results show that an increase in VBP leads to a higher Elastic Modulus. Conversely, an increase in block orientation from 0° (vertical) to 90° (horizontal) reduces the stiffening effect of the rock blocks, resulting in a lower modulus. The interaction plots demonstrate that VBP is most significant for vertically aligned blocks; its influence diminishes as the block orientation increases, nearly reaching the value of the pure matrix for horizontally aligned blocks.

Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the influence of VBP and block orientation on the mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of bimrock through a comprehensive experimental program. The key findings are summarised as follows:

-

RSM and ANOVA confirmed that both VBP and block orientation, as well as their interaction, are statistically significant factors influencing the mechanical properties of bimrock.

-

The UCS exhibits strong anisotropy, controlled by the interplay of VBP and block orientation. Increasing VBP generally leads to a significant reduction in UCS. However, the magnitude of this strength reduction diminishes as the block orientation increases from 0° (vertical) to 90° (horizontal).

-

The elastic modulus is highly dependent on both parameters. An increase in VBP results in a higher modulus, but this stiffening effect is most pronounced for vertically aligned blocks (0°). As the orientation increases towards 90°, the load-carrying contribution of the blocks diminishes, and the elastic modulus approaches that of the pure matrix.

-

In contrast, Poisson’s ratio showed no consistent correlation with VBP or orientation, indicating it is predominantly governed by the specific, heterogeneous arrangement of blocks in each specimen.

-

The failure path is directly dictated by block orientation, with fracture surfaces exhibiting greater tortuosity as the orientation angle increases. Tensile cracking was identified as the dominant failure mechanism across all tested specimens. Crack density was positively correlated with VBP, with higher block content leading to a greater number of generated cracks.

-

The study conclusively demonstrates that the mechanical behaviour of bimrock is not a simple function of VBP alone but is critically governed by the orientation of the blocks’ relative to the loading direction. This anisotropy must be accounted for in the geotechnical design and stability analysis of bimrock masses.

To further elucidate the micromechanical processes, future studies is recommended to employ X-ray computed tomography to visualize internal crack evolution, combined with Discrete Element Method (DEM) numerical simulations to model the propagation of cracks across different VBPs and block orientations.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Greenly, E. The geology of Anglesey: London. Geological Survey of Great Britain (1919).

Medley, E. W. The engineering characterization of melanges and similar block-in-matrix rocks (bimrocks), PhD Thesis, (University of California, Berkeley, 1994).

Medley, E. W. Uncertainty in estimates of block volumetric proportions in melange bimrock, in International Symposium on Engineering Geology and the Environment. Greece, Athens, 267–272. (1997).

Medley, E. W. Using stereological methods to estimate the volumetric proportions of blocks in melange and similar block-in-matrix (bimrock), in Proceedings Seventh International Congress International Association of Engineering Geology, (Lisbon, Portugal, 1994).

Medley, E. W. & Zekkos, D. Geopractitioner approaches to working with antisocial mélanges. In Mélanges: Processes Formation Societal Significance, Vol. 480 (eds John Wakabayashi & Yildirim Dilek) 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1130/2011.2480(13) (Geological Society of America, 2011).

Napoli, M. L., Barbero, M., Ravera, E. & Scavia, C. A stochastic approach to slope stability analysis in bimrocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 101, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.11.009 (2018).

Napoli, M. L., Barbero, M. & Scavia, C. Tunneling in heterogeneous rock masses with a block-in-matrix fabric. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 138 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104655 (2021).

Qiu, Z. et al. Effects of rock content and Spatial distribution on the stability of soil rock mixture embankments. Sci. Rep. 14, 29088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80812-5 (2024).

Kalender, A., Sonmez, H., Medley, E., Tunusluoglu, C. & Kasapoglu, K. E. An approach to predicting the overall strengths of unwelded bimrocks and bimsoils. Eng. Geol. 183, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.10.007 (2014).

Sonmez, H., Ercanoglu, M., Kalender, A., Dagdelenler, G. & Tunusluoglu, C. Predicting uniaxial compressive strength and deformation modulus of volcanic Bimrock considering engineering dimension. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 86, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2016.03.022 (2016).

Napoli, M. L., Festa, A. & Barbero, M. Practical classification of geotechnically complex formations with block-in-matrix fabrics. Eng. Geol. 301, 106595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106595 (2022).

Lindquist, E. & Goodman, R. Strength and deformation properties of a phydical model melange, in 1st North American Rock Mechanics Symposium, (Texas, Austin, 1994).

Coli, N., Berry, P. & Boldini, D. In situ non-conventional shear tests for the mechanical characterisation of a Bimrock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 48, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.09.012 (2011).

Coli, N., Berry, P., Boldini, D. & Bruno, R. The contribution of geostatistics to the characterisation of some Bimrock properties. Eng. Geol. 137–138, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2012.03.015 (2012).

Sharafisafa, M. et al. Finite-discrete element modelling of fracture development in bimrocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 308 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110346 (2024).

Sheikhpourkhani, A., Bahaaddini, M., Oh, J. & Masoumi, H. Numerical study of the mechanical behaviour of unwelded block in matrix rocks under direct shearing. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03507-7 (2024).

Liu, Y., Sun, S. & Lin, C. High-precision computational modeling of soil-rock mixtures considering realistic shape of rock blocks. Eng. Geol. 323, 107236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107236 (2023).

He, Z. et al. A 3D DEM modeling of soil-rock mixture considering Spatial distribution orientation of blocks. Sci. Rep. 14, 25647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77366-x (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Multiscale numerical investigation into the effects of rock content and rock particle size on the macroscopic and mesoscopic mechanical characteristics of soil rock mixture. Sci. Rep. 15, 7336. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91543-6 (2025).

Li, K. et al. An integrated 3D DEM modeling process for bimrocks considering post-peak behavior and block breakage. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 49, 1688–1709. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.3954 (2025).

Medley, E. Estimating block size distributions of melanges and similar block-in matrix rocks (Bimrocks), in Proc. 5th North American Rock Mechanics Symposium, (Toronto, Canada, 2002).

Sonmez, H., Altinsoy, H., Gokceoglu, C. & Medley, E. Considerations in developing an empirical strength criterion for bimrocks, in 4th Asian Rock Mechanics Symposium ARMS, (2006).

Sonmez, H., Tuncay, E. & Gokceoglu, C. Models to predict the uniaxial compressive strength and the modulus of elasticity for Ankara agglomerate. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.01.011 (2004).

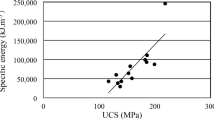

Kahraman, S. & Alber, M. Estimating unconfined compressive strength and elastic modulus of a fault breccia mixture of weak blocks and strong matrix. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 43, 1277–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2006.03.017 (2006).

Afifipour, M. & Moarefvand, P. Mechanical behavior of bimrocks having high rock block proportion. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 65, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.11.008 (2014).

Afifipour, M. & Moarefvand, P. Failure patterns of geomaterials with block-in-matrix texture: experimental and numerical evaluation. Arab. J. Geosci. 7, 2781–2792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-013-0907-4 (2014).

Avşar, E. Contribution of fractal dimension theory into the uniaxial compressive strength prediction of a volcanic welded Bimrock. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 3605–3619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-01778-y (2020).

Yazdani, A., Karimi-Nasab, S. & Jalalifar, H. Shear behavior and dilatancy of an artificial hard-matrix bimrock: an experimental study focusing on the role of blocky structure. Rock. Mech. Bull. 3, 100149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rockmb.2024.100149 (2024).

Hu, Y., Sun, S. & Wei, J. Effect of cementation degree on shear characteristic and failure mechanism of bimrocks containing gravels of different sizes. Lithosphere 2022 https://doi.org/10.2113/2022/1334579 (2022).

Wang, Y., Feng, W. K., Li, C. H. & Hou, Z. Q. An investigation into the effects of block size on the mechanical behaviors of bimsoils using variable-angle shear experiments. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-020-8812-0 (2020).

Xu, W. J. & Zhang, H. Y. Research on the effect of rock content and sample size on the strength behavior of soil-rock mixture. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 2715–2726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-02050-z (2021).

Li, K., Sun, S., Le, H., Wei, J. & Hu, Y. Study on uniaxial compressive strength of double matrix bimrocks considering different block proportions. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, 293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03324-y (2023).

Wakabayashi, J. & Medley, E. W. Geological characterization of melanges for engineering applications, in Proceedings of the 9th International Association for Engineering Geology Congress. (Durban, South Africa, 2004).

Cruden, D., Cruden, D. M. & Varnes, D. J. Landslide Types and Processes, Special Report, Transportation Research Board, National Academy of Sciences, 247:36–75. Special Report - National Research Council, Transportation Research Board 247, 76 (1996). (1996).

Hungr, O., Leroueil, S. & Picarelli, L. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides 11, 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0436-y (2014).

Bucher, K. & Grapes, R. Petrogenesis of metamorphic rocks (8th edition). (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011).

Wan, Y., Zhao, X., Wünnemann, B., Ling, S. & Zeng, C. Flow behavior of phyllite bimrocks having the orientation of blocks. Arab. J. Geosci. 15 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10026-4 (2022).

Napoli, M. L., Barbero, M. & Scavia, C. Effects of block shape and inclination on the stability of melange bimrocks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 7457–7466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02419-8 (2021).

Lindquist, E. S. The strength and deformation properties of melange, PhD Thesis, (University of California, Berkeley, 1994).

Jiang, Y. et al. A strength prediction model of soil-rock mixture with varying rock proportions. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03963-9 (2024).

Li, K. et al. An experimental investigation of effects of block shape on the mechanical properties of bimrocks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84, 477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-025-04518-2 (2025).

Khorasani, E., Amini, M., Hossaini, M. & Medley, E. Statistical analysis of bimslope stability using physical and numerical models. Eng. Geol. 254, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.03.023 (2019).

Medley, E. & Goodman, R. E. Estimate the block volumetric proportions of melange and similar block-in-matrix (bimrock), in 1st North American Rock Mechanics Symposium, (Texas, Austin, 1994).

Napoli, M. L., Milan, L., Barbero, M. & Scavia, C. Identifying uncertainty in estimates of bimrocks volumetric proportions from 2D measurements. Eng. Geol. 278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105831 (2020).

Ulusay, R. & Hudson, J. A. The complete ISRM suggested methods for rock characterization, testing and monitoring: 1974–2006: International Society of Rock Mechanics. (2007).

ASTM. Standard test method for splitting tensile strength of intact rock core specimens. ASTM-D-3967 United States: ASTM International. (2008).

ASTM. Standard test methods forcompressive strength and Elastic moduli of intact rock core specimens under varying states of stress and temperatures. ASTM-D-7012 United States: ASTM International. (2023).

Bahaaddini, M. Numerical study of the mechanical behaviour of rock joints and non-persistent jointed rock masses, PhD thesis, UNSW Australia, (2014).

Bahaaddini, M. Effect of boundary condition on the shear behaviour of rock joints in the direct shear test. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 50, 1141–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1157-z (2017).

Azimi, G. & Papangelakis, V. G. Mechanism and kinetics of gypsum–anhydrite transformation in aqueous electrolyte solutions. Hydrometallurgy 108, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2011.03.007 (2011).

Sadeghiamirshahidi, M. & Vitton, S. J. Analysis of drying and saturating natural gypsum samples for mechanical testing. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 11, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.08.007 (2019).

Hoek, E. & Martin, C. Fracture initiation and propagation in intact rock–a review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 6, 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2014.06.001 (2014).

Xie, W. Q., Liu, X. L., Zhang, X. P., Liu, Q. S. & Wang, E. Z. A review of test methods for uniaxial compressive strength of rocks: theory, apparatus and data processing. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 17 (3), 1889–1905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.05.003 (2025).

Bahaaddini, M. & Hosseinpour Moghadam, E. Evaluation of empirical approaches in estimating the deformation modulus of rock masses. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 3493–3507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-018-1347-x (2019).

Szwedzicki, T. A hypothesis on modes of failure of rock samples tested in uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 40, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-006-0096-5 (2007).

Szwedzicki, T. & Shamu, W. The effect of discontinuities on strength of rock samples, in Proceedings of the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. 23–28 (1999).

Mahdevari, S. & Maarefvand, P. An investigation into the effects of block size distribution function on the strength of bimrocks based on large-scale laboratory tests. Arab. J. Geosci. 9 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-016-2499-2 (2016).

Pirzada, M. A., Bahaaddini, M., Moradian, O. & Roshan, H. Evolution of contact area and aperture during the shearing process of natural rock fractures. Eng. Geol. 291, 106236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106236 (2021).

Pirzada, M., Bahaaddini, M., Andersen, M. & Roshan, H. Coupled hydro-mechanical behaviour of rock joints during normal and shear loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 1219–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03106-0 (2023).

Lv, A., Bahaaddini, M., Masoumi, H. & Roshan, H. The combined effect of fractures and mineral content on coal hydromechanical response. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02669-0 (2022).

Sun, X., Li, X., Zheng, B., He, J. & Mao, T. Study on the progressive fracturing in soil and rock mixture under uniaxial compression conditions by CT scanning. Eng. Geol. 279, 105884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105884 (2020).

Asadizadeh, M., Hossaini, M. F., Moosavi, M., Masoumi, H. & Ranjith, P. G. Mechanical characterisation of jointed rock-like material with non-persistent rough joints subjected to uniaxial compression. Eng. Geol. 260, 105224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105224 (2019).

Bahaaddini, M., Sharrock, G., Hebblewhite, B. K. & Mitra, R. Statistical analysis of the effect of joint geometrical parameters on the mechanical properties of non-persistent jointed rock masses, in 46th US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium. Chicago, USA, (2012).

Boukhatem, G. et al. Optimization of clayey soil parameters with aeolian sand through response surface methodology and a desirability function. Sci. Rep. 15, 30831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91543-6 (2025).

Bahaaddini, M., Hagan, P. C., Mitra, R. & Hebblewhite, B. K. Numerical study of the mechanical behaviour of non-persistent jointed rock masses. Int. J. Geomech. 16, 040150351–040150310. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000510 (2016).

Rabiei-Vaziri, M., Tavakoli, H. & Bahaaddini, M. Statistical analysis on the mechanical behaviour of non-persistent jointed rock masses using combined DEM and DFN. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02674-3 (2022).

Yang, W. H. & Tarng, Y. S. Design optimization of cutting parameters for turning operations based on the Taguchi method. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 84, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(98)00079-X (1998).

Myers, R. H. & Montgomery, D. C. Response surface methodology: Process and product optimization using designed experiments. Vol. 705 (2002).

Funding

The authors declare that this research was carried out without any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology: R. R., M. B.; Conceptualization: M. B., M.H. Kh.; Investigation: R. R., M. B.; Visualization: R. R., M. B.; Validation: R. R., M. B., M.H. Kh.; Supervision: M. B., M.H. Kh.; Formal analysis: R. R., M. B.; Writing – original draft: R. R., M. B.; Writing – review & editing: M.H. Kh.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rostamlo-Jooshin, R., Bahaaddini, M. & Khosravi, M.H. Experimental and statistical analysis of the block orientation effect on the mechanical behaviour of bimrocks. Sci Rep 16, 2279 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32136-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32136-1