Abstract

The effect of the habitat conditions on the pollen features of invasive species has not been studied so far, and may affect the quality of their generative reproduction and contribute to the development of more effective methods of their control. Three species invasive in Europe and Poland were selected for the study - Impatiens parviflora DC., Impatiens glandulifera Royle and Impatiens capensis Meerb. The morphology and intraspecific variability of pollen grains in three Impatiens species growing under different habitat conditions were examined. Specimens were sampled from 198 sites throughout Poland, covering 10 ecologically distinct habitat types. In total, 5940 pollen grains were analysed in respect to the length of the polar axis (P), equatorial diameter (E), exine thickness (Exp), P/E, Exp/P ratios, and exine ornamentation and ectocolpi arrangement. Our research showed that the three studied species can be distinguished based on their palynomorphology. The most important traits were: exine ornamentation and ectocolpi arrangement, pollen size (P, E) and exine thickness (Exp). A relationship between the habitat conditions prevailing in the analysed habitats and the pollen grain characteristics was found, especially in I. glandulifera. In this species pollen size (P, E) increases in the optimal habitat conditions such as edges of reservoirs and watercourses, and decreases in the suboptimal habitat conditions such as anthropogenic habitats. A similar pattern is observed in I. parviflora, where optimal habitats such as mesic mixed coniferous forest favour larger pollen grains, whereas suboptimal habitats like swamp forest are associated with reduced pollen size. In I. capensis, optimal conditions also correspond to edges of watercourses, while suboptimal conditions include swamp forest. Additionally, exine thickness (Exp) may represent an adaptive trait, reflecting plant response to growth and development in unfavorable environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Impatiens Riv. ex L. is a large and highly diverse genus of the family Balsaminaceae representing 1120 accepted species distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. The only native Impatiens species in Europe is Impatiens noli-tangere L1,2. Several non-native species have been introduced, mainly for their ornamental appeal. Some of these have escaped cultivation, spreading uncontrollably and becoming naturalized or even invasive3. This study focuses on three alien Impatiens species found across Europe, including in Poland: Impatiens parviflora DC., Impatiens glandulifera Royle, and Impatiens capensis Meerb. These species have become well-established, are continuously expanding their range, and pose a significant threat to native ecosystems and species.

I. parviflora is native to Central and Eastern Asia, typically found in regions located between 1000 and 2500 m above sea level. In Europe, the species was first recorded in the wild in 1831 in Geneva, Switzerland, following an escape from a botanical garden. Subsequently, it was frequently reported as a garden escapee in countries such as Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic4. Today, I. parviflora is widespread throughout Central Europe, France, the UK, as well as in Scandinavia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Its secondary range extends beyond Europe, also including East Asia, Western, and Northeastern America3,4,5. Currently, in terms of the ecological diversity of habitats it occupies, I. parviflora is considered one of the most adaptable vascular plants6,7. Nevertheless, it has not been listed among the IAS (Invasive Alien Species) of European Union concern. Research on its impact on biodiversity and the species composition of plant communities indicates that it is a relatively weak competitor, and species-rich forest undergrowth may serve as an effective barrier to its spread7,8,9. I. glandulifera is native to Central Asia, specifically the western Himalayas (Pakistan, India, and Nepal), where it thrives at altitudes ranging from 2000 to 4000 m above sea level10. The species was first introduced outside its native range in 1839, in the United Kingdom to the botanical garden in Kew11 and subsequently to other European countries, primarily for its attractive, nectar-rich flowers. It escaped cultivation and rapidly spread across Europe, often utilizing river valleys for efficient seed dispersal, colonizing not only riparian habitats but also forests and other non-riparian environments12,13,14. Beyond Europe, its introduced range includes regions such as the Russian Far East, Canada, the United States, Argentina, Ethiopia, New Zealand, and Tasmania2. In 2017, I. glandulifera was included in the list of invasive alien species of concern to the European Union15. This species is considered a threat to biodiversity, as it can alter soil microbial communities, including bacteria and fungi16, and affect the composition and abundance of certain invertebrate groups17,18,19. It inhibits the germination of other plant species20 and reduces species diversity in the plant communities it invades17,21. Additionally, it competes with native plants for pollinators22,23. I. capensis is native to North America. It was first recorded in Europe in 1822 in the United Kingdom, likely introduced as an ornamental plant that later escaped cultivation and spread24. The species was subsequently noted in France in 189825. During the 20th century, it was introduced or accidentally transported to Finland, Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, and Switzerland. Its introduced range also includes the western part of North America (Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia), northern Mexico, and Japan2,26,27,28. Although I. capensis is not listed among the invasive alien species of concern to the European Union, it is considered invasive in some European countries, including Poland, where it was classified as a widely distributed invasive alien species posing a threat to the country under the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 9 December 202229,30. Despite being regarded as the least competitive of the three mentioned alien Impatiens species present in Europe, there is no doubt that it poses a threat to native habitats protected under EU law31,32,33. Furthermore, it outcompetes native plants in attracting pollinating insects by producing higher amounts of floral attractants, which are attractant semiochemicals that draw various groups of pollinators, primarily bumblebees and bees, thereby significantly increasing its reproductive success34.

Impatiens species occur from sea level to 4000 m altitude, often in forest understoreys, roadside ditches, valleys, abandoned fields, along streams and in seepage, usually in mesic or wet conditions, but some species can tolerate drier habitats35. Despite the rapid and extensive spread of I. parviflora, its habitat preferences and the entire spectrum of plant communities it inhabits are still not fully known. Apart from various types of anthropogenic/transformed habitats, it is widespread in the undergrowth of deciduous forests, especially Sub-Atlantic and medio-European oak or oak-hornbeam forests of the Carpinion betuli, Galio-Carpinetum oak-hornbeam forests, alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior, and riparian mixed forests along major rivers8. This species can occur on a wide range of soils, from strongly acidic to slightly calcareous, provided they are loose, well-aerated, with a good water supply but not waterlogged, and contain moderate or high levels of nutrients, not necessarily calcareous. The subsoil is alluvial (mud, deposit, sand, gravel) or loess. Based on its light requirements, it is a shade-tolerant or semi-shade-tolerant plant36,37. I. glandulifera has a wide range of habitats but prefers areas with high productivity and moderate disturbances. Due to its hygromorphic structure, the presence of the plant is almost exclusively limited to wet habitats. It is most commonly found along streams, rivers, and riparian vegetation, primarily in willow shrubs, alluvial willow-poplar forests, and tall herbaceous fringe communities. The plant prefers rich, humic clay, loam, and alluvial soils37. Most authors believe that soil acidity is insignificant, but according to Soó36, the plant prefers calcareous soils. It does not occur in saline or alkaline soils. Ecological preferences of this species are reflected in the Ellenberg indicator values assigned to the species: soil moisture F = 8, soil reaction (pH) R = 7, and soil nutrient content N = 738. In Poland, I. capensis found its optimum in the Circeo-Alnetum riparian forest as one of the main components of the herb layer in the terrestrial variety of the reed rush Scirpo-Phragmitetum var. with Solanum dulcamara and the mannagrass reed bed and riparian tall herb fringe communities31. It prefers moist to wet soils with a relatively wide pH range, from slightly acidic to neutral, and highly variable organic matter content – from as low as 5.6% to as high as 69.2% – covering mineral, mineral-organic, and organic soil types. The concentrations of macro- and micronutrients in the soils where I. capensis occurs also show substantial variation (e.g. potassium, magnesium, calcium, silicon, zinc, lead), indicating that the species exhibits considerable ecological plasticity in relation to soil chemistry, which likely facilitates its successful establishment across diverse habitats39.

Taxonomically, genus Impatiens is notoriously difficult to classify26,35,40, due to the high levels of convergent evolution on flower morphology, which was probably the main reason why it has been so difficult in the past to divide the genus Impatiens into natural groups based on macromorphological data only41,42. Therefore, several palynological review papers have been written, examining to what extent morphological pollen features can contribute to solving the classification problems of this genus43,44,45,46,47. Palynological studies on the large genus Impatiens were numerous and mainly concern selected African and Asian Impatiens species1,42,44,45, ].

Pollen morphology of the two studied species (I. parviflora and I. glandulifera) has been described only by Halbritter et al.49,50. Huynh51 and Erdtman52 for the first time described pollen grains of a few species from the genus Impatiens. Palynological studies were continued by Janssens et al.1,42,45,47 and Cai XiuZhen et al.48. Janssens with different research teams (2005, 2009, 2012, 2018) investigated the pollen morphology and palynological evolution of several hundred African and Asian Impatiens taxa and described pollen grains of this species. Cai XiuZhen et al.48 described the pollen morphology of 10 Impatiens species from China. Yu et al.35 studied the phylogeny of 150 Impatiens species representing all clades recovered by previous phylogenetic analyses. Pechimuthu et al.46 studied 18 Impatiens species from India and showed a very large variability in the characteristics of their pollen. Halbritter et al.49,50 gave a brief description of the pollen grains of eight species of the genus Impatiens (including I. parviflora and I. glandulifera). He et al.53, after examining the pollen morphology of the 35 Impatiens species, concluded that it plays an important role in the taxonomic classification of this genus.

Wrońska-Pilarek et al.54 and Wiatrowska et al.55,56, indicated that certain pollen features, particularly grain size (P and E) and exine thickness (Ex), are responsive to habitat conditions. Khaleghi et al.57 indicated that salinity can influence pollen size and exine ornamentation, suggesting that soil composition can directly affect pollen structure. Similarly, Vasilevskaya58 reported that air pollution and heavy metal deposition are associated with morphological abnormalities in pollen grains, potentially reducing pollen viability and altering exine patterns. Furthermore, Mehmood et al.59 demonstrated that climatic factors, particularly high temperatures, can disrupt pollen development, reduce germination rates, and modify pollen morphology, which may have significant implications for reproductive efficiency under changing environmental conditions.

The main objective of this study was to investigate, for the first time, habitat-related variation in pollen morphology of three species across ten distinct habitat types. These species were selected for the study as the most expansive from the genus Impatiens in Europe and in Poland. Another important objective was to perform detailed, complete descriptions of pollen morphology of the studied species based on a large sample of pollen, which were missing in the palynological literature, and to examine the inter- and intraspecific variability of pollen grains, which had not been analysed before, also the pollen of I. capensis have not been studied so far.

The results of our research on pollen morphology of invasive Impatiens species constitute one aspect of assessing the response of pollen to changing habitat conditions. Supplemented with research on pollen viability and pollen fertility, they could be used to develop more effective methods for controlling invasive Impatiens species in natural habitats.

We hypothesized that the pollen features that would most respond to changing habitat conditions would be the exine ornamentation, pollen size (P, E) and exine thickness (Ex).

Materials and methods

Palynological analysis

Flowers were collected from 198 locations representing 10 distinct habitat types, mainly forested areas across various regions of Poland (see Supplementary Table S1, Fig. S1). The study sites were chosen to capture the diversity of habitats in which the three studied species occur within Poland. The number and distribution of sampled sites also reflect the current spread of each species in Poland: I. parviflora is widespread and commonly encountered throughout the country, I. glandulifera is less frequent but still occurs in many regions, while I. capensis remains limited to the north-western part of Poland, where it occupies a relatively small area60,61. Collected specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Botany and Forest Habitats, Poznań University of Life Sciences (PZNF), and its identification was carried out by the persons responsible for the collection (see Supplementary Table S1).

Each sample consisted of 30 randomly selected, mature and properly developed pollen grains, in accordance with the study by Wrońska-Pilarek et al.62, derived from a single plant occurring in a given habitat. In total, 5940 pollen grains of Impatiens were analysed (3930 from I. parviflora, 1680 from I. glandulifera, and 330 from I. capensis) including 4050 from forest habitats, 1140 from semi-natural habitats, and 750 from anthropogenic habitats. From forest habitats, the counts were: mesic coniferous forest 210, mesic mixed coniferous forest 450, moist mixed coniferous forest 60, mesic mixed broadleaved forest 930, moist mixed broadleaved forest 90, mesic broadleaved forest 990, moist broadleaved forest 480, and swamp forest 840. The pollen grains were prepared for light (LM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using the method described by Erdtman63,64. The acetolysis mixture was made up of 9 parts of acetic acid anhydride and one part of concentrated sulphuric acid and the process of acetolysis lasted 2.5 min. The prepared material was divided into two parts: one part was immersed in an alcohol solution of glycerine (for LM) and the other in 96% ethyl alcohol (for SEM). The LM study of acetolysed pollen grains was performed using a Levenhuk D870T microscope at 400× magnification of. To study exine pattern morphology in SEM pollen samples were mounted onto aluminium stubs with double-sided adhesive tape. Stubs were sputter-coated with gold-palladium, and pollen was examined and imaged using a Zeiss Evo 10.

Pollen grains were analysed for five quantitative features, i.e. length of polar axis (P), equatorial diameter (E), thickness of exine (Ex), exactly Exp (thickness of the exine along the polar axis), and P/E, Exp/P ratios, as well as the following qualitative traits: pollen outline and shape and exine ornamentation. The pollen size was determined according to Erdtman’s63 classification based on the length of the polar axis (P). The pollen shape classes (P/E ratio) were adopted according to the classification proposed by Erdtman63: suboblate (0.75–0.88), oblate-spheroidal (0.89–0.99), spheroidal (1.00), prolate-spheroidal (1.01–1.14), subprolate (1.15–1.33), prolate (1.34–2.00) and perprolate (> 2.01).

The palynological terminology used in the study according to Punt et al.65 and Halbritter et al.66.

Habitats analysis

The collected pollen samples were arranged in a habitat gradient from the poorest to the most fertile habitats. A total of 198 pollen samples (I. parvifora – 131, I. glandulifera – 56, I. capensis – 11) were collected from 10 different habitats, mainly forests (Table 1). The habitat type was determined in each place from which plant material was collected based on expert knowledge. Due to the great diversity of these areas, the habitats were grouped into 10 categories corresponding to plant communities according to Sikorska and Lasota67 and Matuszkiewicz68 (Table 1). The largest number of samples was collected from semi-natural habitats, such as the unforested edges of large and small rivers and watercourses (38). The second group consisted of samples collected from anthropogenic sites (25), mainly roadsides. The largest group consists of natural – forest sites (in order of increasing habitat fertility): mesic coniferous forest (7), mesic mixed coniferous forest (15), moist mixed coniferous forest (2), mesic mixed broadleaved forest (31), moist mixed broadleaved forest (3), mesic broadleaved forest (33), moist broadleaved forest (16) and swamp forest (28). In the analysed species, optimal and suboptimal habitats differed depending on their ecological requirements. For example, edges of reservoirs and watercourses represented optimal conditions for both I. glandulifera and I. capensis, whereas anthropogenic sites were suboptimal for I. glandulifera but optimal for I. parviflora. Among forest habitats, mesic mixed coniferous forest provided optimal conditions for I. parviflora, while swamp forest functioned as a suboptimal habitat type for both I. parviflora and I. capensis.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated for each trait and each habitat. Coefficients of variation were calculated for each trait. Density plots were used to present distribution of the data. The analyses were performed for sample means. The Shapiro-Wilk’s normality test69 was used to check the normal distribution of the five traits for each species of Impatiens. All the traits had normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test was carried out to determine the effects of Impatiens samples on the variability of P, E, Exp, P/E and Exp/P. Bartlett’s test was utilized to test the homogeneity of variance. The relationships between the five observed traits were estimated using Pearson’s linear correlation coefficients based on the means of Impatiens species. A canonical variance analysis was applied to assess similarity of Impatiens species in a lower number of dimensions. Cluster analysis was used to group the habitats, using Ward’s method of hierarchical grouping and the measure of Euclidean distance70. The Ball and Hall criterion was incorporated to establish the proper cluster count. Before the cluster analysis, the traits were standardized to follow the normal distribution with zero mean and variance equal to 1. The statistical analyses were performed using the ‘ggplot2’, ‘NbClust’, ‘corrplot’, ‘car’ and ‘pheatmap’ packages in the R program (version 4.4.2)71.

Results

General morphological description of pollen

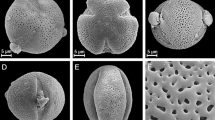

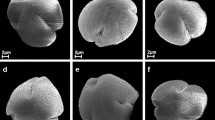

A description of pollen grains of the Impatiens species was given below and illustrated in the SEM photographs (Fig. 1). The morphological observations for the other quantitative features of pollen grains were shown in Table 2 and see Supplementary Tables S2–4.

Pollen grains of the three studied Impatiens species were isopolar monads (Figs. 1A–F and 2). They were tetracolpate, and more precisely – brevicolpate (brevicolpus is short colpus situated equatorially). The pollen outline in the equatorial view was usually rectangular or pentagonal with the rounded corners and in the polar view irregular – mostly elliptic (Figs. 1A–F and 2). According to the pollen size classification by Erdtman63, analysed pollen grains are mostly medium sized (25.1–50 μm; 99.66%), very rarely small (10–25 μm; 0.34%), with small pollen grains occurring exclusively in I. glandulifera.

The mean length of the polar axis (P) was 34.40 (19.10–49.62) µm. One can notice that the species I. glandulifera and I. capensis had nearly identical means (29.16 μm and 28.97 μm, respectively), whilst I. parviflora had a much higher mean (37.10 μm) (Table 2; Fig. 3). The same can be stated about the traits E and Exp. However, the Exp/P ratio has almost the same means (0.022, 0.023 and 0.021 for I. parviflora, I. glandulifera and I. capensis, respectively) (Table 2; Fig. 3). The longest pollen grains were found in I. parviflora compared to the other two species. The values of P were 37.10 (24.98–49.62) µm in I. parviflora, 29.16 (19.10–36.89) µm in I. glandulifera and 28.97 (25.33–34.29) µm in I. capensis (Table 2; Fig. 3).

The mean equatorial diameter (E) was 21.64 (12.31–36.37) µm. The values of this trait were 23.60 (15.15–36.37) µm in I. parviflora, 17.98 (12.31–23.30) µm in I. glandulifera and 16.83 (14.11–20.20) µm in I. capensis. The narrowest range of E variation was found in I. capensis (14.11–20.20 μm), and the widest in I. parviflora (15.15–36.37 μm) (Table 2; Fig. 3).

The mean thickness of the exine along the polar axis (Exp) was 0.750 (0.390–1.190) µm. The exine was thickest in I. parviflora (0.797 μm) and I. glandulifera (0.664 μm) and thinnest in I. capensis (0.609 μm) (Table 2; Fig. 3).

The P/E ratio (pollen shape) was 1.610 (0.992–2.314). The values of this ratio were 1.586 (0.994–2.313) for I. parviflora, 1.631 (0.992–2.314) for I. glandulifera and 1.729 (1.400–2.118) for I. capensis (Table 2; Fig. 3). The most frequently observed pollen grains were prolate (96.45%–5729 grains) and subprolate (2.07%–123). In addition, 1.26% (75) of the grains were perprolate in shape. The least frequently represented were the pollen of the two shape classes: prolate-spheroidal (0.19%–11) and oblate-spheroidal (0,03%–2). We analysed the distribution of pollen shape classes in individual taxa. In each of the taxa, prolate pollen was found to be the most numerous (I. parviflora – 3765, I. glandulifera – 1639, I. capensis – 325), while subprolate pollen was the second most abundant shape in I. parviflora (112) and I. glandulifera (11). Among the remaining pollen shapes, perprolate pollen was most numerous in I. parviflora (41), followed by I. glandulifera (29) and I. capensis (5). The least abundant pollen shapes were oblate-spheroidal in I. parviflora and I. glandulifera (1 grain each).

The Exp/P ratio mean was 0.020 (0.010–0.050). The values of this ratio were 0.022 (0.010–0.050) for I. parviflora, 0.023 (0.013–0.042) for I. glandulifera and 0.021 (0.016–0.030) for I. capensis (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Exine ornamentation was reticulate – heterobrochate (reticulate pollen wall with lumina of different sizes) with a few to a dozen free-standing short and massive columellae of different diameters placed in the lumina (Figs. 1G–I). The muri were from quite thin to thick, of varying heights, with an irregular, slightly wavy or straight course. The lumina were irregular in outline, usually from tetragonal to hexagonal and of varying diameters from 0.94 to 2.73 μm. The colpus membrane was psilate. The species studied differ in exine ornamentation. I. parviflora is distinguished by the most distinct ornamentation, the muri in this species was of medium thickness, but high and with an irregular, wavy course, the lumina was 4–6 angular, with different, often quite large diameters (1.5–2 μm), and the free-standing columellae, as in all three species, were very numerous, several to a dozen in the lumina, single or “merging into several” and irregularly arranged in the lumina. I. capensis was distinguished by the thickest, high muri with a straight course, and I. glandulifera had the least distinct exine ornamentation, because its muri were thin, low and flattened, with a straight course. The lumina diameters of the last two species were slightly smaller than in I. parviflora.

All studied pollen belonged to the pollen class tetracolpate, because they have four apertures (colpi) and to the type brevicolpate (brevicolpus – the short colpus situated equatorially). Colpi are arranged in pairs in the equatorial area, closer to the center or on the edges of pollen grains. The colpi are elliptical, short, very narrow, and elongated, tapering at pointed tips, with regular, distinct colpus margins. In I. glandulifera and in I. capensis, colpi are located at the edge of the pollen at a distance from the pole equal to about 1/6 of the length of the polar axis (P), whereas in I. parviflora, colpi are placed closer to the middle of the pollen, at a distance to about 1/4 of the length of the polar axis (P) (Fig. 2).

The analysis of variance displayed that there are significant differences between Impatiens species for all traits [P (F = 580.3***), E (F = 356.7***), Exp (F = 84.67***), P/E (F = 32.3***), Exp/P (F = 6.351**), *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01]. According to Tukey’s multiple comparison test for the traits E and P/E there are significant differences between all species. For the traits P and Exp there are significant differences between I. parviflora and I. glandulifera and between I. parviflora and I. capensis. Lastly, for the trait Exp/P there is significant difference only between I. parviflora and I. capensis (Fig. 3; Table 2).

The analysis of the first two canonical variables of 198 Impatiens samples for five traits is presented in Fig. 4. In the graph, the coordinates of points are equal to the values of the first and second canonical variates. It can be seen that I. parviflora is distant from I. glandulifera and I. capensis. The first two canonical variates accounted jointly for 100% of the total variability. Significant positive linear relationships of the original traits with the first canonical variable were found for the traits P (0.982), E (0.942) and Exp (0.720), whilst the significant negative relationships were found for P/E (-0.432) and Exp/P (-0.194). For the second canonical variate the only significant relationships were found for P/E (0.443) and Exp/P (-0.307).

The correlation coefficients between traits are presented in Supplementary Figure S2. For I. parviflora significant positive correlations were found between P and E (0.81), and between Exp and Exp/P (0.92). The significant negative correlations were found between P and P/E (-0.23), P and Exp/P (-0.46), E and P/E (-0.76) and E and Exp/P (-0.35). Moreover, for I. glandulifera significant positive correlations were found between P and E (0.71), and between Exp and Exp/P (0.92). The significant negative correlations were found between P and Exp/P (-0.60), E and Exp (-0.28), E and P/E (-0.71) and E and Exp/P (-0.52). Lastly, for I. capensis the significant positive correlation was found between Exp and Exp/P (0.91). The significant negative correlations were found between P and Exp/P (-0.76) and E and Exp/P (-0.62).

Effects of various conditions in the studied habitats on pollen traits

The analysis of variance did not reject the null hypothesis of similar habitat means for I. parviflora and I. capensis species (Figs. 5 and 7). However, there are significant differences for traits P, E and Exp/P for the I. glandulifera species. For all three aforementioned traits, according to Tukey’s multiple comparison test, there are significant differences between edges of reservoirs and watercourses and anthropogenic habitats (Fig. 6).

For I. parviflora species the highest mean for the length of the polar axis (P) 37.77 (31.34–45.88) µm was reported for the mesic mixed coniferous forest and the lowest mean 36.63 (27.66–49.62) µm was reported for the swamp forest. For the equatorial diameter (E) the highest value 24.34 (17.90–33.99) µm was reported for the mesic mixed coniferous forest and the lowest value 23.06 (15.15–33.50) µm was reported for the swamp forest. For the exine thickness (Exp) the highest mean 0.872 (0.530–1.450) µm was reported for the moist mixed coniferous forest, whilst the lowest mean was 0.749 (0.460–1.100) µm for the mesic mixed coniferous forest. For the P/E ratio the highest mean 1.605 was reported for both the moist mixed coniferous forest (1.267–2.077) and the swamp forest (1.127–2.313) and the lowest mean 1.561 was reported for the moist broadleaved forest (1.222–2.011) and the mesic mixed coniferous forest (1.196–1.997). For the Exp/P ratio the highest mean 0.024 (0.014–0.041) was reported for the moist mixed coniferous forest and the lowest mean 0.020 (0.011–0.032) was reported for the mesic coniferous forest (see Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 5).

Boxplot and density plots of five pollen grains traits of I. parviflora in relation to the 10 habitat types studied. Abbreviations of the habitats types names see in Table 1.

For I. glandulifera species the highest mean for the length of the polar axis (P) 29.51 (19.25–36.17) µm was reported for the edges of reservoirs and watercourses and the lowest mean 28.49 (19.10–36.89) µm was reported for the anthropogenic. For the equatorial diameter (E) the highest value 18.34 (14.02–23.30) µm was reported for the edges of reservoirs and watercourses and the lowest value 17.41 (12.55–22.78) µm was reported for the anthropogenic. For the exine thickness (Exp) the highest mean 0.685 (0.430–1.030) µm was reported for the anthropogenic habitat, whilst the lowest mean was 0.649 (0.450–0.970) µm for the edges of reservoirs and watercourses. For the P/E ratio the highest mean 1.647 (1.267–2.183) was reported for the anthropogenic habitat and the lowest mean 1.617 (0.992–2.144) was reported for the edges of reservoirs and watercourses. For the Exp/P ratio the highest mean 0.024 (0.013–0.042) was reported for the anthropogenic habitat and the lowest mean 0.022 (0.015–0.035) was reported for the edges of reservoirs and watercourses (see Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 6).

For I. capensis. species there were only two habitats: the edges of reservoirs and watercourses and the swamp forest. Higher trait means were reported for the swamp forest, with the exception of the equatorial diameter (E). For the swamp forest the reported means were 29.21 (25.33–34.29) µm for the length of the polar axis (P), 16.79 (14.11–20.20) µm for the equatorial diameter (E), 0.616 (0.500–0.800) µm for the exine thickness (Exp), 1.748 (1.510–2.118) for the P/E ratio and 0.021 (0.017–0.030) for the Exp/P ratio. For the edges of reservoirs and watercourses the reported means were 28.84 (25.33– 30.23) µm for the length of the polar axis (P), 16.85 (14.43–19.56) µm for the equatorial diameter (E), 0.602 (0.500– 0.790) µm for the exine thickness (Exp), 1.718 (1.400–2.001) for the P/E ratio and 0.021 (0.016–0.030) for the Exp/P ratio (see Supplementary Table S4, Fig. 7).

Canonical variance analysis was performed for all three species. The first two canonical variates accounted jointly for 80.4% (I. parviflora) (Fig. 8), 94.9% (I. glandulifera) (Fig. 9) and 100% (I. capensis) of the total variability. Due to there being only two habitat types reported for I. capensis, the first canonical variable contained 100% of the total variability and thus the biplot is not included. For I. parviflora one could notice that the pollen grains in the moist broadleaved forest habitat and the moist mixed broadleaved forest habitat were slightly separate from pollen grains in the rest of the distinguished types of habitats(Fig. 8). For I. glandulifera pollen grains in the moist broadleaved forest habitat were slightly separate from pollen grains in the other habitat types (Fig. 9). For I. parviflora, significant positive linear relationships of the original traits with the first canonical variable were found for the traits Exp (0.21) and Exp/P (0.28). For the second canonical variate the only positive significant relationships were found for P (0.39) and E (0.47), whilst the only negative significant relationships were found for P/E (-0.44) and Exp/P (-0.18). For I. glandulifera, significant positive linear relationships of the original traits with the first canonical variable were found for the traits Exp (0.51), P/E (0.40) and Exp/P (0.74), whilst significant negative linear relationships were found for traits P (-0.73) and E (-0.78). For the second canonical variate the only positive significant relationships were found for E (0.31), whilst the only negative significant relationships were found for Exp (-0.53) and Exp/P (-0.48).

In Supplementary Figure S3, extended heat maps with the results of cluster analysis for all traits over habitats in each species were displayed. The standardization of data was conducted before the analysis. Based on the Ball and Hall criterion, there were three main clusters for the I. parviflora species, three main clusters for the I. glandulifera species and two main clusters for the I. capensis species. For I. parviflora the first cluster consisted of the following habitats: moist mixed coniferous forest, swamp forest, edges of reservoirs and watercourses and lastly mesic mixed broadleaved forest. The habitats in this cluster had below average means for traits P and E, and above average means for traits Exp, P/E and Exp/P. The second cluster contains the following habitats: moist mixed broadleaved forest, anthropogenic habitat and mesic coniferous forest. This cluster featured habitats for which all traits had means below average. Lastly, the third cluster consisted of the following habitats: mesic mixed coniferous forest, mesic broadleaved forest and moist broadleaved forest. The habitats in this cluster were characterized by above average means for traits P and E, average values for traits Exp and Exp/P and below average values for the trait P/E. For I. glandulifera the anthropogenic habitat was the only habitat in the first cluster, due to below average means for traits P and E, and above average means for traits Exp, P/E and Exp/P. In contrast, the second cluster, consisting of only edges of reservoirs and watercourses, featured above average means for traits P and E, and below average means for traits Exp, P/E and Exp/P. The last cluster consisted of the moist broadleaved forest and swamp forest and it was characterized by average values for all traits. Lastly, for I. capensis there were only two habitats (edges of reservoirs and watercourses and swamp forest), which designated the first and second clusters respectively. For the edges of reservoirs and watercourses habitat means of traits P, Exp, P/E and Exp/P had below average values, whilst the trait E had above average value. Contrary to that, the swamp forest habitat had above average values for traits P, Exp, P/E and Exp/P, whilst the trait E had below average value.

Discussion

Bigazzi and Selvi72 suggested that palynological features were not changeable with environmental changes and have strong selection forces at work in dispersal, water-stress, pollination, germination, stigmatic interactions and possess strong taxonomic characteristics for species-genera identifications. The thesis regarding conservative character of the pollen and its significance is supported by Grey-Wilson40,41 and Erdtman73. Many scholars claim that the analysis of micromorphological features of the plants (pollen or spores) is highly valuable, especially in an instance of genera that are taxonomically complex, such as Impatiens1,46,48,53. Tuler et al.74 and Grímsson et al.75 pointed out the importance of pollen characters to plant classification at the intergeneric level. Palynological studies have provided some insight into the direction of plant evolution35,76. Pollen studies cited underneath confirm the significance of exine ornamentation in analysis of the Impatiens genus, and according to Attique et al.77 reticulate exine ornamentation increases their structural strength and surface friction coefficient, facilitating interactions with pollinating insects and enhancing the efficiency of pollen transfer by insects.

Pollen research of the large genus Impatiens is quite extensive. Huynh51 for the first time described pollen grains in genus Impatiens as a reticulate rectangular with four apertures. Erdtman52 confirmed those features and added that pollen grains of Impatiens were bilateral, subisopolar, reticulate and usually medium sized. Janssens et al.45 described pollen of families Balsaminaceae, Tetrameristaceae and Pellicieraceae confirmed aforementioned pollen features. Long-term pollen studies on Impatiens genus was carried out by Janssens1,42,47. In 2005 those were palynotaxonomic studies on 11 African and 8 Asian taxa from genus Impatiens1. Yu et al.35 analysed the phylogeny of 150 Impatiens species representing all clades recovered by previous phylogenetic analyses, as well as three outgroups. The authors identified two main types of Impatiens pollen grains (tri- and tetracolpate), and the tetracolpate pollen were further subdivided into four subtypes: orbicular, quadrate, oblong, and elliptic. Janssens et al.47 described evolutionary trends of the genus Impatiens by researching the pollen morphology of 115 Asian species, basing their conclusions on pollen types (3 or 4-aperturate), sexine ornamentation (from reticulate to microreticulate) and pollen shape (from triangular to circular, quadrangular, elliptic to subelliptic and rectangular). The authors concluded that although some pollen morphological characters seem to be homoplasious, others help to improve the resolution of some phylogenetically problematic lineages in this genus. In another research paper, Janssens et al.1 researched pollen of the 63 African Impatiens species, which were various in size (medium to large), outline (circular, rectangular or elliptic) and shape (oblate, peroblate and suboblate). Most of the studied species had a reticulate exine ornamentation (homobrochate and heterobrochate). Cai XiuZhen et al.48 described the pollen grains of 10 species of Impatiens as small or medium sized, long-elliptic, goniotreme with two types of the reticulate exine ornamentation distinguished on the basis of granules types. According to those authors, the exine ornamentation differentiates these species, and as such it can be used to identify them. Pechimuthu et al.46 researched 18 Impatiens species from India and recognized these traits as diagnostic: sexine ornamentation (reticulate and echinate, just in I. fruticosa), type of pollen symmetry (radial or bilateral), type of polarity (heteropolar or isopolar), pollen size (small or medium), and pollen type (di-, tri- or tetracolpate). According to aforementioned authors the variability of the pollen features were useful for the identification and classification of the genus Impatiens and the high structural pollen diversity renders important taxonomic value for species differentiation. He et al.53 after researching the pollen morphology of the 35 species of genus Impatiens concluded that features such as pollen type (2, 3, 4 – colporate), length of polar axis (P), equatorial diameter (E) play a crucial role in identifying Impatiens species. Halbritter et al.49,50 gave one, synthetic description of pollen of I. parviflora and I. glandulifera, and as previously mentioned, I. capensis has not been yet researched. They described the pollen grains of eight species from genus Impatiens as a izopolar monads, medium sized (21–40 μm), belonging to the pollen class tri- and tetracolpate and with pollen shape usually quadrangular or elliptic. Pollen was often flattened (wider than long) and the exine ornamentation was reticulate with free-standing columellae in the lumina. Our results generally support the previously described pollen characters of Impatiens including reticulate exine ornamentation, tetracolpate apertures, and medium pollen size reported by Huynh51, Erdtman52, Janssens et al.1,42,45,47, Cai XiuZhen et al.48, and He et al.53. However, due to the exceptionally large number of samples analysed in our study, we recorded narrower and more precise ranges of pollen size and shape, as well as clearer differences in exine ornamentation among the three species. In particular, the pronounced ornamentation in I. parviflora, the less distinct muri in I. glandulifera, and the thick, straight muri in I. capensis refine and complement earlier descriptions, which were often based on limited material. These findings demonstrate that some interspecific differences were previously underestimated and highlight the value of large, geographically diverse datasets in resolving pollen morphological variability within the genus Impatiens.

Our results showed that habitat conditions influenced pollen morphological traits of the studied species, but the strength of their influence varied. The most significant influence was found in I. glandulifera. This finding partly supports the view that pollen grains are conservative plant organs78, whose morphological characteristics remain relatively stable regardless of environmental conditions.

In I. glandulifera, the traits P, E, and Exp/P were most strongly responsive to habitat conditions. Studies on other plant species also indicate that habitat properties can influence pollen morphology, although the strength and direction of this response may vary between taxa. Wiatrowska et al.55 showed that habitat conditions affected quantitative pollen traits of Reynoutria japonica and R. ×bohemica, whereas no such effect was observed in R. sachalinensis. In R. japonica, differences between habitats were found, among others, in traits P, E and Exe, and in R. ×bohemica in P, Exp and Exe. In Stapylea pinnata, Cu, Zn, and CaCO₃ contained in the soil were found to influence pollen morphology in this species. Thus, the exine thickness (Ex) was positively correlated with CaCO₃ content, pollen size (traits P and E) with Cu, and pollen shape (P/E ratio) with Zn56. Wrońska-Pilarek et al.79 also demonstrated the response of exine thickness (Ex) of pollen grains to habitat conditions prevailing in natural localities of Convallaria majalis. It is therefore possible that pollen size (traits P, E) and the exine thickness (Ex), were the pollen traits to which the response in I. glandulifera was observed, and which are sensitive to habitat properties.

In light of the studies cited, which demonstrate links between palynomorphological traits and edaphic factors, particularly soil chemical composition, it is worth clarifying how these findings relate specifically to our results. Unlike research in which the influence of individual soil elements (for example Cu, Zn or CaCO₃) on pollen grain size or exine thickness was directly demonstrated55,56, our analyses were based on habitat-type gradients rather than on direct measurements of edaphic parameters. Nevertheless, the patterns we observed, such as the increased pollen size of I. glandulifera in the most fertile and moist habitats and the tendency for exine thickening in anthropogenic, potentially more stressful sites, are consistent with the general direction of the relationships reported in experimental and soil-chemistry-based studies. This suggests that the pollen variability detected here may reflect a functional response to habitat conditions, even if edaphic factors influence this response only indirectly through broader trophic and moisture-related characteristics of the habitats. At the same time the lack of significant differences in I. parviflora and I. capensis indicates that these relationships may be strongly species specific, which highlights the need for future research incorporating direct soil analyses, for example micronutrient content, to more clearly link observed palynomorphological responses with specific edaphic drivers.

As mentioned earlier, exine structure influences the reproductive potential of plants, therefore there is no doubt that the reaction of exine thickness (Ex) to habitat conditions is of great importance. The exine thickness (Ex) affects the success of pollen-tube penetration80 and the pollen walls often play a key role in pollen dispersal and in interactions between pollen grains and stigmas78,81. The exine plays a crucial role in facilitating pollen adhesion to the stigma after binding pollen of the same species is also known82. Additionally, the structure of the pollen wall contributes to harmomegathy, a mechanism that helps prevent desiccation in arid environments83. According to Matamoro-Vidal et al.84, the thickness of the exine influences water absorption and the conditions under which pollen grains expand during hydration. Their findings indicate that a thinner exine may not accommodate the increase in cytoplasmic volume during rehydration, potentially leading to the rupture of the pollen wall85.

According to the findings of Wiatrowska et al.55,56, pollen size increases proportionally with the copper content in the soil, which is consistent with previous reports indicating that a deficiency of this element leads to a reduction in pollen size86,87,88. It can be assumed that in S. pinnata, pollen grain size plays an important role in its germination and the growth of the pollen tube, as has also been observed in other plant species89.

It was found that the pollen of I. glandulifera, which apparently responded to changing habitat conditions, produced by plants growing along the edges of water reservoirs and watercourses was larger (traits P and E) and the exine (Ex) was thinner than the pollen collected from plants from anthropogenic habitats. In Europe, I. glandulifera is predominantly associated with riparian habitats10,90. Throughout its European range, this species most frequently colonises and forms dense populations on moist to wet soils that are rich in bases and nutrients. It may also encroach upon drier, more acidic, and less fertile soils, which contributes to its widespread occurrence in several European countries not only in natural habitats, but also in semi-natural and anthropogenically influenced environments such as roadsides91, meadows, field margins, fallows, and various disturbed areas including settlements, parks, and gardens21,92. In invaded riparian habitats, its widespread invasion is regarded as a significant conservation concern90,93,94. It can therefore be assumed that the edges of reservoirs and watercourses are habitats favorable to the growth and development of this species, where it develops the largest pollen grains.

In suboptimal habitats, such as anthropogenically influenced sites, I. glandulifera tends to produce smaller pollen grains. It has also been observed that the exine in these habitats is thicker. Although studies addressing this phenomenon are limited, research investigating the impact of stress factors – such as herbicide exposure – on the morphological characteristics of pollen grains in Prunus serotina revealed that the exine thickness (Ex) in pollen collected from herbicide-treated trees was greater (mean values 0.90–0.95 μm) than in pollen from control trees not exposed to herbicides (0.74 μm)54. These findings suggest that an increase in exine thickness may represent an adaptive response to growth under elevated stress conditions, such as increased sunlight exposure, lower substrate nutrient availability and moisture content, or the presence of pollutants in the soil. A similar pattern appears to be present in I. capensis, where increased exine thickness has also been observed under less favourable habitat conditions. According to Myśliwy et al.39, swamp forest environments – typically assumed to be optimal for this species – may in fact impose physiological stress due to excessive shade. As I. capensis is relatively sensitive to low light availability, such conditions may trigger structural adaptations of pollen grains, including thickening of the exine layer, as a potential protective mechanism.

Canonical variance analysis showed that for I. parviflora, the pollen of this species comes from plants growing in fertile and moist habitats, which are slightly separate from the other habitats where the plant occurs. Similarly, in the case of I. glandulifera, the moist broadleaved forest habitat was slightly separate from all other distinguished habitats, indicating that habitat humidity may have an effect on the pollen size of these species (Figs. 8 and 9).

Cluster analysis of all pollen traits across habitats for each studied species revealed that the pollen groups according to the environmental characteristics of their respective habitats. Habitat-related variability in pollen morphology was greatest in I. parviflora and I. glandulifera, both of which colonize habitats that differ substantially in terms of fertility and moisture. In contrast, I. capensis exhibited the lowest trait variability, likely due to its occurrence being restricted, within the study area, to relatively similar habitats – namely, the edges of reservoirs and watercourses, as well as swamp forests.

This analysis also showed that I. parviflora produces the largest pollen grains with relatively thick exine (with P, E, and Exp values above the mean) in mesotrophic or eutrophic habitats of moderate fertility. In contrast, in anthropogenic habitats and the driest sites (e.g., mesic coniferous forest), the pollen grains are smaller with thinner exine. In wet habitats, this species develops small pollen grains, but with thick exine. I. glandulifera forms large or medium-sized pollen grains mainly in fertile and highly moist habitats (such as moist broadleaved forests, swamp forests, and the edges of reservoirs and watercourses). In anthropogenic habitats, it produces small pollen grains, but with a relatively thick exine. In the case of I. capensis, drawing broader conclusions is difficult, as the habitats where the species occurs – and from which the research material was collected – are highly similar in their environmental characteristics.

Conclusions

-

1.

Our research showed that the three studied species of the genus Impatiens can be distinguished based on morphological characteristics of the pollen. The most important qualitative features were exine ornamentation and ectocolpi arrangement, which distinguished all studied species. The most important biometric features were P and E, and to a lesser extent P/E and Exp. These were used to distinguish one species – I. parviflora, whose pollen was the largest and least elongated, with the thickest exine.

-

2.

Relations were found between the habitat conditions prevailing in the analysed habitats and the morphological characteristics of the pollen grains of the studied species. The strongest influence of habitat conditions on pollen morphology was observed in I. glandulifera, where a detailed analysis of the mean values for the traits P, E, Exp/P across different habitats revealed significant differences in how environmental factors affect pollen structure. It is therefore possible that three pollen features are sensitive to habitat properties.

-

3.

Our results support previously described patterns indicating an increase in pollen size under optimal habitat conditions and a decrease in size under suboptimal ones. They also suggest that exine thickness may represent an adaptive trait that responds sensitively to growth and development under unfavourable environmental conditions. For instance, pollen of I. parviflora collected from individuals growing in wetland habitats – considered suboptimal for this species – exhibited thick exines (Exp above the mean). A similar pattern was observed in I. glandulifera, where pollen from plants occurring in highly anthropogenically altered habitats also showed increased exine thickness, as described above.

-

4.

In conclusion, the results of the presented research on the impact of habitat conditions on the pollen morphology and variability of the studied invasive species may contribute to explaining their adaptive and ecological success, and ultimately their invasive potential. Potential disruption of the generative reproduction of these species could be used to develop more effective methods for controlling these invasive species. Identifying habitats that promote optimal pollen development may help prioritise areas for targeted removal, while recognising sites where pollen development is suboptimal can guide more efficient allocation of management efforts.

-

5.

The presented findings suggest a promising direction for future research, focused on establishing stronger links between environmental conditions and pollen grain characteristics, including their viability. Integrating detailed habitat assessments – such as soil properties, moisture levels, and light availability – into studies may, in turn, provide deeper insights into the invasion dynamics of these alien species. Future work incorporating functional reproductive metrics, such as pollen viability, germination capacity, and seed set, would allow verification of the ecological relevance of the observed morphological patterns and provide a more complete understanding of their role in reproductive success.

Data availability

Data concerning pollen grain measurements will be made available by the corresponding author, whereas the remaining data are included in the manuscript and the supplementary materials.

References

Janssens, S. B., Knox, E. B., Dessein, S. & Smets, E. F. Impatiens msisimwanensis (Balsaminaceae): Description, pollen morphology and phylogenetic position of a new East African species. S Afr. J. Bot. 75, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2008.08.003 (2009).

POWO. Plants of the World Online. http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org (Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, 2024).

Adamowski, W. Balsams on the offensive: the role of planting in the invasion of Impatiens species. In Plant Invasions: Human Perception, Ecological Impacts and Management (eds Tokarska-Guzik, B. et al.) (Backhuys, 2008).

Trepl, L. Über Impatiens parviflora DC. Agriophyt in mitteleuropa. Diss Bot. 73, 1–400 (1984).

NOBANIS. European Network on Invasive Alien Species. http://www.NOBANIS.org (2024).

Myśliwy, M. Habitat preferences of some neophytes, with a reference to habitat disturbances. Pol. J. Ecol. 63, 509–524. https://doi.org/10.3161/104.062.0311 (2014).

Reczyńska, K., Świerkosz, K. & Dajdok, Z. The spread of Impatiens parviflora DC. in central European oak forests – another stage of invasion? Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 84, 401–411. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp.2015.039 (2015).

Obidziński, T. & Symonides, E. The influence of the groundlayer structure on the invasion of small Balsam (Impatiens parviflora DC.) to natural and degraded forests. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 69, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp.2000.041 (2000).

Hejda, M. What is the impact of Impatiens parviflora on diversity and composition of herbal layer communities of temperate forests? PLoS One. 7, e39571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039571 (2012).

Helsen, K. et al. Biological flora of central Europe: Impatiens glandulifera Royle. PPEES 50, 125609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2021.125609 (2021).

Lhotská, M. & Kopecký, K. Zur verbreitungsbiologie und Phytozönologie von Impatiens glandulifera royle an Den flussystemen der Svitava, Svratka und oberen Odra. Preslia 38, 376–385 (1966).

Beerling, D. J. & Perrins, J. M. Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Impatiens roylei Walp). J. Ecol. 81, 367–382. https://doi.org/10.2307/2261507 (1993).

Tokarska-Guzik, B. The Establishment and Spread of Alien Plant Species (Kenophytes) in the Flora of Poland (Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2005).

Čuda, J., Skálová, H. & Pyšek, P. Spread of Impatiens glandulifera from riparian habitats to forests and Ist associated impacts: insights from a new invasion. Weed Res. 60, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12400 (2020).

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU). 2017/1263 of 12 July 2017 updating the list of invasive alien species of Union concern established by Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJ L 182, 13.7.2017, p. 37). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2017/1263/oj (2017).

Gaggini, L., Rusterholz, H-P. & Baur, B. The invasive plant Impatiens glandulifera affects soil fungal diversity and the bacterial community in forests. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 124, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.11.021 (2017).

Tanner, R. A. An Ecological Assessment of Impatiens Glandulifera in its Introduced and Native Range and the Potential for its Classical Biological Control (PhD thesisUniversity of London, 2011).

Ruckli, R., Rusterholz, H-P. & Baur, B. Invasion of Impatiens glandulifera affects terrestrial gastropods by altering microclimate. Acta Oecol. 47, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2012.10.011 (2013).

Rusterholz, H. P., Salamon, J. A., Ruckli, R. & Baur, B. Effects of the annual invasive plant Impatiens glandulifera on the collembola and Acari communities in a deciduous forest. Pedobiologia 57, 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2014.07.001 (2014).

Ruckli, R., Hesse, K., Glauser, G., Rusterholz, H-P. & Baur, B. Inhibitory potential of naphthoquinones leached from leaves and exuded from roots of the invasive plant Impatiens glandulifera. J. Chem. Ecol. 40, 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-014-0421-5 (2014).

Kiełtyk, P. & Delimat, A. Im pact of the alien plant Impatiens glandulifera on species diversity invaded vegetation in the Northern foothills of the Tatra Mountains, Central Europe. Plant. Ecol. 220, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-018-0898-z (2019).

Chittka, L. & Schürkens, S. Successful invasion of a floral market. Nature 411, 653. https://doi.org/10.1038/35079676 (2001).

Najberek, K., Solarz, W., Wysoczański, W., Węgrzyn, E. & Olejniczak, P. Flowers of impatiens glandulifera as hubs for both pollinators and pathogens. NeoBiota 87, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.87.102576 (2023).

Perring, F. M. & Walters, S. M. Atlas of the British Flora: 96 (Thomas Nalson and Sons Ltd, 1962).

Fournier, P. Les quatre flores de France. In (ed. Chevalier, P.) (FFESSM, 1961).

Akiyama, S. A new record of Impatiens (Balsaminaceae) in Honshu. Bull. Nation Sci. Mus. B (Tokyo). 26, 61–65 (2000).

Zika, P. F. Impatiens ×pacifica (Balsaminaceae), a new hybrid Jewelweed from the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Novon 16, 443–448 (2006). 10.3417/1055–3177(2006)16[443:IPBANH]2.0.CO;2.

Rewicz, A., Myśliwy, M., Rewicz, T., Adamowski, W. & Kolanowska, M. Contradictory effect of climate change on American and European populations of Impatiens capensis Meerb. – is this herb a global threat? Sci. Total Environ. 850, 157959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157959 (2022).

Tokarska-Guzik, B. et al. Alien plants in Poland with particular reference to invasive species (Generalna Dyrekcja ochrony Środowiska, [in Polish with English summary]. (2012).

Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 9. December 2022 on the list of invasive alien species posing a threat to the Union and the list of invasive alien species posing a threat to Poland, remedial actions, and measures aimed at restoring the natural state of ecosystems (Journal of Laws of 16 December 2022, item 2649) https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220002649 [in Polish] (2022).

Pawlaczyk, P. & Adamowski, W. Impatiens capensis (Balsaminaceae) – a new species in the flora of Poland. Fragm Flor. Geobot. 35, 225–232 (1991). [in Polish].

Matthews, J. et al. Risks and management of non-native Impatiens species in the Netherlands http://repository.ubn.ru.nl/handle/2066/149286 (Radboud University, FLORON, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, 2015).

Rewicz, A., Myśliwy, M., Adamowski, W., Podlasiński, M. & Bomanowska, A. Seed morphology and sculpture of invasive Impatiens capensis Meerb. from different habitats. PeerJ 8, e10156. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10156 (2020).

Jakubska-Busse, A., Czeluśniak, I., Hojniak, M., Myśliwy, M. & Najberek, K. Chemical insect attractants produced by flowers of Impatiens spp. (Balsaminaceae) and list of floral visitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 17259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417259 (2023).

Yu, S. X. et al. Phylogeny of Impatiens (Balsaminaceae): integrating molecular and morphological evidence into a new classification. Cladistics 32, 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12119 (2016).

Soó, R. & Priszter, S. A. Systematic and Geobotanical Synopsis of the Flora and Vegetation of Hungary: Phytogeography of Hungary and the Systematic Treatment and Ecological–Phytogeographical Characterization of Its Higher Organized (Vascular) Plants (Akadémiai Kiadó, 1996) [in Hungarian].

Botta-Dukát, Z. & Balogh, L. The Most Important Invasive Plants in Hungary (Institute of Ecology and Botany Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2008).

Ellenberg, H. & Leuschner, C. Vegetation Mitteleuropas Mit Den Alpen: in ökologischer, Dynamischer Und Historischer Sicht (Neografia, 2010). [in German].

Myśliwy, M. et al. Could alien impatiens capensis invade habitats of native I. noli-tangere in Europe? – Contrasting effects of microhabitat conditions on species growth and reproduction. NeoBiota 99, 171–200. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.99.142196 (2025).

Grey-Wilson, C. Impatiens of Africa (CRC, 1980).

Grey-Wilson, C. Hybridisation in African Impatiens. Studies in balsaminaceae. Kew. Bull. 34, 689–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/4119063 (1980b).

Janssens, S. B. et al. A total evidence approach using palynological characters to infer the complex evolutionary history of the Asian Impatiens (Balsaminaceae). Taxon 61, 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.612007 (2012).

Rahman, F. et al. Palynological characterization and taxonomic delimitation of the genus Impatiens L. in Pakistan: an LM and SEM study. Microsc Res. Tech. 88, 2512–2527. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.24843 (2025).

Song, Y. X., Hu, T., Peng, S., Cong, Y. Y. & Hu, G. W. Palynological and macroscopic characters evidence infer the evolutionary history and insight into pollination adaptation in Impatiens (Balsaminaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 62, 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12959 (2024).

Janssens, S. et al. Palynological variation in balsaminoid Ericales. II. Balsaminaceae, Tetrameristaceae, Pellicieraceae and general conclusions. Ann. Bot. 96, 1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci257 (2005).

Pechimuthu, M., Arumugam, R. & Ponnusamy, S. Pollen morphology of the genus Impatiens L. (Balsaminaceae) and its systematic implications. Acta Biol. Szeged. 64, 207–219. https://doi.org/10.14232/abs.2020.2.207-219 (2020).

Janssens, S. B., Vinckier, S., Bosselaers, K., Smets, E. F. & Huysmans, S. Palynology of African Impatiens (Balsaminaceae). Palynol 43, 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2018.1509149 (2018).

Cai XiuZhenCai, X. Z. et al. SEM observation on the pollen grains of ten species in Impatiens L. (Balsaminaceae). Bull. Bot. Res. 3, 279–283 (2007).

Halbritter, H., Heigl, H. & Auer, W. Impatiens parviflora. In PalDat - A Palynological Database. https://www.paldat.org/pub/Impatiens_parviflora/306261 (2021).

Halbritter, H., Heigl, H. & Auer, W. Impatiens glandulifera. In PalDat - A Palynological Database. https://www.paldat.org/pub/Impatiens_glandulifera/306259 (2021).

Huynh, K. L. Morphologie du pollen des Tropaeolacées et des Balsaminacées. I. Morphologie du pollen des Tropaeolacées. Grana 8, 88–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00173136809427463 (1968).

Erdtman, G. Pollen Morphology and Plant Taxonomy (Hafner, 1971).

He, H. et al. Studies on the characteristics of Impatiens pollen and its taxonomic significance from Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. Preprint at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4254836 (2022).

Wrońska-Pilarek, D. et al. How do pollen grains of Convallaria majalis L. Respond. Different Habitat Conditions? Diversity. 15, 501. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15040501 (2023).

Wiatrowska, B. et al. Intra-and interspecific pollen morphology variation of invasive Reynoutria taxa (Polygonaceae) in their response to different habitat conditions. NeoBiota 98, 61–92. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.98.138657 (2025a).

Wiatrowska, B. et al. The effect of soil physicochemical properties on intraspecific variability of pollen morphology in Staphylea pinnata L. Sci. Rep. 15 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14136-3 (2025).

Khaleghi, E., Karamnezhad, F. & Moallemi, N. Study of pollen morphology and salinity effect on the pollen grains of four Olive (Olea europaea) cultivars. S Afr. J. Bot. 127, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2019.08.031 (2019).

Vasilevskaya, N. Pollution of the environment and pollen: A review. Stresses 2, 515–530. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses2040035 (2022).

Mehmood, M., Tanveer, N. A., Joyia, F. A., Ullah, I. & Mohamed, H. I. Effect of high temperature on pollen grains and yield in economically important crops: a review. Planta 261, 141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-025-04714-0 (2025).

Zając, A. & Zając, M. Distribution Atlas of Vascular Plants in Poland (Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie, 2001). [in Polish].

Zając, A. & Zając, M. Distribution Atlas of Vascular Plants in Poland: Appendix (Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie, 2019) [in Polish].

Wrońska-Pilarek, D., Jagodziński, A. M., Bocianowski, J. & Janyszek, M. The optimal sample size in pollen morphological studies using the example of Rosa canina L. Rosaceae. Palynol 39, 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2014.933748 (2015).

Erdtman, G. Pollen Morphology and Plant Taxonomy. Angiosperms. An Introduction To Palynology (Almquist and Wiksell, 1952).

Erdtman, G. The acetolysis method. A revised description. Sven Bot. Tidskr. 54, 561–564 (1960).

Punt, W., Hoen, P. P., Blackmore, S., Nilsson, S. & Le Thomas, A. Glossary of pollen and spore terminology. Rev. Palaeobot Palynol. 143, 1–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.06.008 (2007).

Halbritter, H. et al. Illustrated Pollen Terminology. Second Edition (Springer, 2018).

Sikorska, E. & Lasota, J. Typological habitat classification system and phytosociological habitat assessment. Studia I Materiały Centrum Edukacji Przyrodniczo-Leśnej. 9, 44–51 (2007). (in Polish).

Matuszkiewicz, W. Guide To Identifying Plant Communities in Poland (Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2022). [in Polish].

Shapiro, S. S. & Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611 https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591 (1965).

Mahalanobis, P. C. On the generalized distance in statistics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India A. 12, 49–55 (1936). (1936).

Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R. Core Team, 2025).

Bigazzi, M. & Selvi, F. Pollen morphology in the Boragineae (Boraginaceae) in relation to the taxonomy of the tribe. Pl Syst. Evol. 213, 121–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988912 (1998).

Erdtman, G. Pollen Morphology and Plant Taxonomy 3rd edn (E.J. Brill, 1986).

Tuler, A. C. et al. Taxonomic significance of pollen morphology for species delimitation in Psidium (Myrtaceae). Pl Syst. Evol. 303, 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-016-1373-8 (2017).

Grímsson, F., Grimm, G. W. & Zetter, R. Evolution of pollen morphology in Loranthaceae. Grana 57, 16–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00173134.2016.1261939 (2018).

Rull, V. An updated review of fossil pollen evidence for the study of the origin, evolution and diversification of Caribbean mangroves. Plants. 12, 3852 https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12223852 (2023).

Attique, R. et al. Pollen morphology of selected melliferous plants and its taxonomic implications using microscopy. Microsc Res. Tech. 85, 2361–2380. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.24091 (2022).

Stace, C. A. Plant Taxonomy and Biosystematics (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Wrońska–Pilarek, D. et al. The effect of herbicides on morphological features of pollen grains in Prunus serotina Ehrh. In the context of elimination of this Invasive species from European forests. Sci. Rep. 13, 4657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31010-2 (2023).

Wang, R. & Dobritsa, A. A. Exine and aperture patterns on the pollen surface: their formation and roles in plant reproduction. Annu. Plant. Rev. Online. 1, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119312994.apr0625 (2018).

Rejón, J. D. et al. The pollen coat proteome: At the cutting edge of plant reproduction. Proteome. 4, 5 https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes4010005 (2016).

Katifori, E., Alben, S., Cerda, E., Nelson, D. R. & Dumais, J. Foldable structures and the natural design of pollen grains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7635–7639 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911223107 (2010).

Oorts, K. C. In Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and their Bioavailability, Environ. Pollut. (ed. Alloway B. J.) 22, 367–394 (2010).

Matamoro-Vidal, A. et al. Links between morphology and function of the pollen wall: an experimental approach. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 180, 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12378 (2016).

Lisci, M., Tanda, C. & Pacini, E. Pollination ecophysiology of Mercurialis annua L. (Euphorbiaceae), an anemophilous species flowering all year round. Ann. Bot. 74, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1994.1102 (1994).

Agarwala, S. C., Chatterjee, C., Sharma, P. N., Sharma, C. P. & Nautiyal, N. Pollen development in maize plants subjected to molybdenum deficiency. Can. J. Bot. 57, 1946–1950. https://doi.org/10.1139/b79-244 (1979).

Pandey, N., Gupta, M. & Sharma, C. P. Ultrastructural changes in pollen grains of green gram subjected to copper deficiency. Geophytology 25, 147–150 (1996).

Sancenón, V. et al. The Arabidopsis copper transporter COPT1 functions in root elongation and pollen development. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15348–15355. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M313321200 (2004).

Bertin, R. I. Paternity in plants. In Plant Reproductive Ecology. Patterns and Strategies (eds Doust, J. L. & Doust, L. L.) (Oxford University Press, 1988).

Pyšek, P. & Prach, K. Invasion dynamics of Impatiens glandulifera—a century of spreading reconstructed. Biol. Conserv. 74, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(95)00013-T (1995).

Follak, S. et al. Invasive alien plants along roadsides in Europe. EPPO Bull. 48, 256–4265. https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12465 (2018).

Kostrakiewicz-Gieralt, K. The effect of habitat conditions on the abundance of populations and selected individual and floral traits of Impatiens glandulifera Royle. Biodiv Res. Conserv. 37, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/biorc-2015-0002 (2015).

Pyšek, P. & Prach, K. Plant invasions and the role of riparian habitats a comparison of four species alien to central Europe. J. Biogeogr. 20, 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4018-1_23 (1993).

Hejda, M. & Pyšek, P. What is the impact of Impatiens glandulifera on species diversity of invaded riparian vegetation? Biol. Conserv. 123, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.03.025 (2006).

Funding

The publication was financed by the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education as part of the Strategy of the Poznań University of Life Sciences for 2024–2026 in the field of improving scientific research and development work in priority research areas and co-financed by the Minister of Science under the “Regional Excellence Initiative” Program for 2024–2027 (RID/SP/0045/2024/01) and statutory funds of the Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin, Poland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DWP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. KL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation. KB: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. MM: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. BT-G: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation. LK: Data curation. B.W: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wrońska-Pilarek, D., Lechowicz, K., Banaś, K. et al. Pollen morphology of three invasive Impatiens species in Europe under varying habitat conditions—a case study from Poland. Sci Rep 16, 2729 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32427-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32427-7