Abstract

One of the primary challenges with ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) is its high cement content, typically around 1000 kg/m3, which raises significant environmental concerns. Therefore, reducing cement content while maximizing its efficiency is essential for improving both the sustainability and performance of UHPC. This study focuses on developing an environmentally friendly UHPC mix with a reduced cement content of 700 kg/m3, reinforced with hybrid fibers: steel fiber (StF) and polypropylene fiber (PPF). The main objective of this research is to evaluate the effects of these two fiber types on the mechanical properties and durability of UHPC. It also aims to achieve a balance between enhanced strength, crack resistance, and load-bearing capacity under various conditions. Fiber volume percentages ranging from 0%, 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, and 3% were incorporated for both StF and PPF, used as single or hybrid fibers. The study assessed several key mechanical and durability properties, including compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, modulus of elasticity, porosity, water absorption, sorptivity, fire resistance, impact resistance, and energy absorption. Additionally, the microstructural properties were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). In addition, the life cycle assessment (LCA) of UHPC was evaluated in terms of cost-effectiveness, energy efficiency, and carbon efficiency. Among the tested UHPC blends, despite the relatively low cement content, the mix containing 0.75% StF and 0.25% PPF demonstrated superior performance, achieving a compressive strength of 155 MPa, tensile strength of 5 MPa, and flexural strength of 4 MPa, which outperformed the mix containing 3% mono-StF. Furthermore, this hybrid fiber combination exhibited up to a 47% increase in initial and final kinetic energy absorption compared to its mono-StF counterpart. The hybrid blend of 0.75% StF and 0.25% PPF also showed reduced porosity (1.73%), lower water absorption (0.602%), and decreased saturation absorption (16.6%) compared to the monofilament StF mix. SEM analysis further confirmed that the hybrid fiber composition improved the fiber-matrix interface and reduced porosity. Furthermore, among all the mixes, the control and 3P mixes showed the highest environmental efficiency and reduced carbon emissions, energy consumption and costs. These results indicate that hybrid fiber systems can significantly enhance the mechanical performance, impact resistance, and durability of UHPC while simultaneously promoting the use of environmentally friendly cementitious compositions. This highlights the potential of hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC for advanced structural applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) is an advanced cementitious material that has garnered widespread global interest since its development in the early 1990’s, due to its exceptional mechanical properties, enhanced durability, and superior performance compared to conventional concrete1,2. Conventional concrete, despite its widespread use, has notable limitations in resource consumption, environmental impact, and thermal performance3,4. UHPC has several key characteristics including high compressive and flexural strength, excellent resistance to chloride penetration, and strong freeze-thaw resistance5,6. A typical UHPC mix consists of cementitious materials (≈ 1000 kg/m3), superplasticizer (SP), fine aggregates, and silica fume (SF), with a low water-to-binder (W/B) ratio of 0.14–0.207,8. Portland cement manufacturing is estimated to contribute approximately 6% of total greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating the issue of climate change9. Despite its outstanding performance, UHPC is often seen as incompatible with contemporary sustainability objectives, particularly due to its substantial environmental impact10,11. Furthermore, the high material costs and considerable CO2 emissions hinder the widespread adoption of UHPC globally12,13.

To align with the concrete industry’s sustainability goals14, it is essential to explore approachs for reducing the cost and carbon footprint of UHPC to facilitate its broader acceptance. One promising approach to mitigating these challenges is the partial replacement of cement in UHPC with sustainable supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as ground-granulated blast-furnace slag, fly ash, and phosphorus slag. This strategy reduces cement consumption while maintaining, or even improving, mechanical performance8. Rapid industrial expansion, urban development, and population growth have led to a substantial rise in waste generation, resulting in large accumulations that pose significant environmental risks15. However, as high-quality SCMs become increasingly scarce, identifying alternative binder materials for UHPC is gaining importance. Among these alternatives, SF has traditionally been used to replace cement due to its ability to refine the microstructure of UHPC. Previous studies have shown that incorporating SF with glass fibers enhances the synergy between concrete performance and sustainability by integrating complementary cementitious materials (SCMs), reducing carbon emissions, and ensuring reliable mechanical and durability properties16. Metakaolin (MK), a pozzolanic material produced by calcining kaolin, presents a viable alternative to cement in UHPC mixtures. It exhibits a particle size comparable to that of silica fume and offers similar pozzolanic activity17,18. Studies have shown that partial replacing of cement with MK can improve the microstructural density and enhance the interfacial transition zone, thereby improving the mechanical properties of UHPC19,20.

Fibers play a crucial role in the performance of UHPC by mitigating its inherent brittleness and improving its tensile strength12,21, Without fibers, UHPC exhibits a brittle tensile strength between 7 and 10 MPa, whereas the inclusion of fibers widens this range to 7–15 MPa14. The presence of fibers, particularly steel fibers (StF), enhance the material’s ability to resist cracking. Due to their high strength and modulus of elasticity, StF provids exceptional crack-bridging. This ability to bridge cracks significantly improves the material’s overall performance and durability, reinforcing the structural integrity of UHPC22. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of monomeric StF (3% by volume) in enhancing the compressive strength of UHPC by approximately 12%. However, no significant improvements were observed when the fiber volume exceeded 3%22. Due to its larger size, StF contributes to bridging wide cracks and preventing their propagation. However, its capacity to prevent the formation of early microcracks remains limited.

Polypropylene fiber (PPF) is widely used in concrete to enhance its durability and crack resistance. Known for their non-corrosive nature and excellent thermal stability, PPF contribute to the improvement of the interfacial bond strength and reduce the formation and propagation of microcracks in the matrix23. Additionally, its hydrophobic surface prevents interference with the hydration process, making them an ideal reinforcement for enhancing the performance of UHPC24. PPF also helps to connect micro-cracks in the interfacial transition zone between the aggregates and the matrix of UHPC25. By combining StF and PPF, UHPC benefits from enhanced durability due to the reduction of fracture initiation and propagation, leveraging the unique properties of both fibers. Replacing StF with PPF can reduce the cost of producing StF-PPF/UHPC and decrease carbon dioxide emissions, thus reducing the social cost of carbon dioxide emissions. It is an effective strategy for achieving environmentally friendly concrete production and has been of great importance in promoting its application in the engineering field26.

The compressive behavior and modulus of elasticity of UHPC are essential for effective structural analysis and design27. While many of the researchers have focused on mono StF or multi-span fiber, the combined effects of hybrid fibers on the performance of UHPC have yet to be fully explored. Furthermore, while the stress-strain behavior of UHPC has been studied, the reinforcement mechanisms of hybrid fibers and the influence of fiber-aggregate interactions on the compression behavior of UHPC remain areas that requiring further investigation28.

Exposure to high temperatures significantly alters the microstructure and properties of cement hydration products, which in turn affects the macroscopic properties and overall performance of concrete29. Due to its low porosity, UHPC faces challenges in releasing vapor pressure under high-temperature conditions, making it more vulnerable to fire damage30. The inclusion of PPF has been shown to reduce chipping and enhance fire resistance by creating pathways for steam release, thus alleviating pressure buildup within the concrete31. Despite this, research on hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC remains limited.

Impact resistance to cracking and fracture is a fundamental characteristic in evaluating the performance of UHPC under dynamic loads. UHPC is particularly susceptible to brittle failure, making it crucial to enhance its ability to resist impact-induced cracking and fracture32. The high compressive strength of UHPC does not necessarily translate to high toughness or impact resistance, which is why reinforcing UHPC with fibers has gained significant attention. Fiber reinforcement, particularly hybrid fiber systems, plays a key role in improving the concrete’s ability to absorb impact energy, bridging cracks, and preventing the propagation of fractures33. Previous studies have shown that combining 2% hybrid fibers with 10% SF not only improved compressive strength but also resulted in the highest impact resistance (58.2 kN m)34.

To overcome the limitations of previous studies, a comprehensive evaluation of UHPC was conducted. This study focused on an environmentally friendly concrete mixes reinforced with StF and PPF, both individually and in hybrid combinations. The primary objective of the research was to assess the impact of fiber content on various properties of UHPC, including its physical properties (workability, porosity, water absorption, and sorptivity), mechanical properties (compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity), and durability. Additionally, the concrete life cycle assessment (LCA), impact resistance and energy absorption were evaluated using repeated drop-weight tests, focusing on crack initiation, propagation, and post-cracking behavior. Microstructural analysis was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to examine the synergistic effects of hybrid fibers within the matrix and to validate their contribution to enhancing concrete performance. Furthermore, the study aimed to determine the optimal ratio of hybrid fibers for UHPC to facilitate its effective application across a variety of structural applications. The findings from this study are expected to contribute valuable insights into the design and performance enhancement of UHPC through the use of hybrid fiber reinforcement.

Experimental methodology

Figure 1 presents a flow chart of the research methodology employed in this study, outlining the materials utilized, measurement techniques, and testing procedures implemented throughout the investigation.

Materials

In this research, UHPC was produced using Portland cement (PC) (CEM I 52.5 N), compliant with European Standard EN 197-1:201135. To enhance sustainability and improve material properties, SCMs such as SF and MK were used as binders at constant dosages of 25% and 10% by cement weight, respectively. SF, with an average particle size of 0.3 μm, a specific gravity of 2.21 g/cm3, a Blaine fineness of 25,000 m2/kg, and a specific surface area of 20,000 m2/kg, was used in accordance with ASTM C1240-9736 as a pozzolanic and densification material. MK, with a specific gravity of 2.57 g/cm2, Blaine fineness of 19,000 m2/kg, and a specific surface area of 4200 m2/kg, was used to contribute to the microstructure refinement. Table 1 presents the chemical compositions of the utilized binders. Figure 2 displays the particle size distribution of all binder materials used in this study. Quartz powder (QP) with a maximum particle size of 125 μm, a specific gravity of 2.65 g/cm3, and a mean particle size (D50) of 6 μm, was added as a filler to improve particle packing and provide structural stability to the matrix.

Figure 3a–d presents eransmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of various materials used in the study. The PC particles are irregular and angular, with rough surfaces, which contribute to early strength but may affect long-term performance. The SF particles are spherical, ranging from 57.9 to 118.53 nm, and enhance concrete’s strength and durability by reacting with calcium hydroxide to form additional C–S-H gel. MK displays a mix of sheet-like and spherical particles (25.46–82.13 nm), contributing to a denser matrix and improved concrete properties. QP, with angular and rounded particles, provides strength enhancement through its inert filler effect. These images highlight the particle size distribution and structural features of the materials, which are critical for understanding their role in enhancing UHPC.

The fine sand had a specific gravity of 2.70 g/cm3, with particle sizes typically around 0.25 mm. The bulk density, fineness modulus, and water absorption were 1.5 g/cm3, 2.5, and 1%, respectively. The SP (Sika ViscoCrete-5930) contained 32% solids and 68% water by mass. Figure 4 presents the images of the fibers employed in this study, and their key properties are summarized in Table 2. Table 3 details the corresponding fiber content percentages incorporated into the UHPC mixtures.

Mixtures design and mixing procedures

The binder proportions followed the design principles for UHPC mixes, based on previous studies, as outlined in Table 4. All mixes were designed with constant proportions of PC (700 kg/m3), within the typical UHPC range of 650–900 kg/m3, known to produce dense matrices with low porosity and high compressive strength37,38. SF (70 kg/m3), comprising 10% of the binder content, was incorporated, as previous studies suggest that proportions between 5% and 30% optimize particle packing, pozzolanic reactivity, and strength enhancement in UHPC systems39. The inclusion of MK (175 kg/m3) at 25% aligns with findings from prior research indicating that 10–25% MK content significantly enhances C–A–S–H formation, improves pore structure, and reduces shrinkage40.

The selection of 3% StF content was informed by previous studies41, which established that the optimal performance of high-performance concrete is achieved with a StF content of 2% to 3% by volume. This fiber content notably improves the concrete’s mechanical properties and durability while maintaining workability without negatively affecting fluidity. The reference mix was prepared without fibers, while other mixes incorporated a constant total fiber volume ratio of 3% (based on the mix volume). Mono-StF was used in the 3 S mix, while mono-PPF was used in the 3P mix. The hybrid fiber ratios used were 75/25, 50/50, and 25/75, respectively.

The mixing protocol for the environmentally friendly UHPC concrete, as shown in Fig. 5, involved the use of a 30-liter vertical vane mixer with variable speeds. Mixing proceeded by blending all dry materials, including polycarbonate, carbon fibers, and fine sand, for approximately 2 min at 200 rpm. Subsequently, 70% of the total water was added and mixed for 5 min at the same speed. SP and the remaining water were then incorporated, followed by continuous mixing for 6 min at 450 rpm. Finally, StF and PPF were gradually added, and mixing continued for an additional 3 min. The concrete mix was then placed into steel molds and compacted on a vibrating table for 25 s. After placement, the molds were covered with polyethylene sheets to minimize moisture loss. After 24 h, UHPC samples were removed from the molds and cured in a water bath until testing.

Specimen preparation

The effects of the applied variables were evaluated across various UHPC characteristics, including physical properties (slump and density), mechanical properties (compressive strength at 2, 7, 28, and 90 days; splitting tensile strength and flexural strength at 2, 7, and 28 days; and modulus of elasticity at 28 days), as well as durability properties (fire resistance, porosity, and sorptivity), impact resistance at 28 days, and microstructure analysis at 28 days, as shown in Fig. 6a–i. Table 5 summarizes all test parameters and sample dimensions. To assess the workability of the fresh UHPC, slump flow tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM C143/C143M42. As shown in Fig. 6a, three cubic specimens (50 × 50 × 50 mm) were prepared per testing day to determine the compressive strength and unit weight, ensuring accurate results in accordance with ASTM C39/C39M43. Figure 6b illustrates the measurement of splitting tensile strength on cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm, following the Brazilian test method according to ASTM C496/C496M44. Flexural strength testing, shown in Fig. 6c, was conducted on 50 × 50 × 160 mm prisms in accordance with ASTM C1609/C1609M45. For the modulus of elasticity, three cylinders with a diameter of 150 mm and a height of 300 mm were prepared from each mix, as shown in Fig. 6d, according to ASTM C469/C469M-14 (1975)46.

Fire resistance testing of UHPC was conducted by heating 50 × 50 × 50 mm in an electric furnace with a capability of 1400 °C. For simplicity, a constant heating rate of 2 °C/min, as recommended by ASTM E11947, was applied in this study. Compression tests were performed at four target temperatures (200, 400, 600, and 800 °C), with four specimens tested at each temperature to account for potential explosive spalling. After the heating periods of 4 h, the furnace was turned off, and the door was left open for 12 h to allow the specimens to cool down gradually, as shown in Fig. 6e. After 28 days of curing, the samples were removed from the curing tank, and their durability properties, including porosity and water absorption, were evaluated according to ASTM C1754/C1754M-1248. The tests were conducted using 50 × 50 × 50 mm concrete cubes. The testing process involved soaking the samples in water for 24 h to achieve saturation, measuring the submerged weight (A), drying the surfaces to obtain the saturated weight (B), and oven-drying the samples at 105 ± 5 °C to determine the dry weight (C), as shown in Fig. 6f. porosity (%) and water absorption (%) were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

As shown in Fig. 6g, the absorption test was carried out using 50 × 50 × 50 mm cube samples at 28 days of age. sorptivity and water uptake were measured in accordance with ASTM C158549, to evaluate the hydraulic diffusivity and water-transport characteristics of the concrete, which are key indicators of durability50. Equations (3) and (4) illustrate the relationship between sorptivity (S) and water absorption (I).

where; S is sorptivity (measured in mm per square root of time), I is the water absorption (measured in mm), and t is the time elapsed for measurement.

where; mt is the change in mass of the concrete specimen at time t (measured in grams), A is the cross-sectional area of the specimen (7853.9 mm2), and γ is the water density (0.001 g/mm3).

Impact resistance was assessed using the drop-weight test, performed in accordance with ASTM C162151, to evaluate the behavior of fiber-reinforced HHPC under dynamic loading, as shown in Fig. 6h. Cylindrical disc specimens (150 mm diameter, 64 mm height) were subjected to repeated drops of a 12-kg weight from a height of 457 mm. The energy absorption capacity and the number of impacts required to induce visible cracks and complete failure were recorded. The energy absorption capacity of each specimen was then calculated using Eq. (5).

The variables m, V, g, h and n represent the drop mass, velocity at impact, gravitational acceleration, height of fall, and number of impacts, respectively.

Microstructure analysis of the UHPC mixtures was performed using SEM imaging at 28 days, as shown in Fig. 6i. The SEM imaging was carried out using a FE-SEM NOVA on samples taken from previously tested specimens for compressive strength. The samples, prepared in 10 mm size, were dried in a low-temperature oven (70 °C) for 2 h before being analyzed.

Experimental results and discussion

Table 6 presents the measured physical and mechanical properties of the proposed UHPC. Table 7 provides the results for durability properties, including fire resistance testing, sorptivity, water absorption, and porosity, while Table 8 presents the impact resistance results.

Slump flow

Figure 7 shows the results of the effect of hybrid and monofibers on the workability of all mixtures. The slump value of the control mix was 205 mm, while the slump value of the other mixtures ranged from 160 to 185 mm, which is consistent with previous studies53. A noticeable reduction in the UHPC slump was observed for mixes incorporated hybrid fiber, particularly the 25 S-75P mixture, which exhibited an 18% decrease in slump, compared to control mix. This reduction is attributed to the influence of PPF fibers on the cohesion and water distribution within the concrete matrix, consistent with the findings of Meng and Khayat54. The presence of PPF reduced flowability by increasing interactions between the fibers and cementitious materials. Furthermore, with an increase in PPF, the fiber distribution within the matrix becomes less uniform, leading to the formation of air voids between the fibers, which in turn increases viscosity and impairs the flow of the mixture. Although the addition of StF caused a slight decrease in workability compared to control mix, all mixtures maintained sufficient fluidity for practical applications, indicating that the reduction in workability remained within acceptable limits (160–185 mm).

Dry density

Figure 8 illustrates the hardened density of all UHPC mixtures, including both hybrid and mono-fiber types. The results show a general trend of decreasing concrete density as the StF content decreases and the PPF content increases, which aligns with previous studies22,55. This trend can be attributed to the lower density of PPF compared to StF, resulting in a reduction of overall concrete density with increasing PPF proportion56. Among all mixes, the 3 S mixture exhibited the highest density, while the 3P mixture showed the lowest density relative to the hybrid fiber mixes. The inclusion of PPF, being lighter than the concrete matrix, consequently reduces the overall density of the UHPC.

Compressive strength

Figure 9 shows the average compressive strength values for all mixtures at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days and 90 days. At 90 days of curing, the compressive strength ranged from 110 to 155 MPa, which is consistent with the values reported by Smarzewski and Barnat-Hunek in couple of research25,55. The addition of StF resulted in increased compressive strength at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days and 90 days by providing additional structural support, improving stiffness and cohesion, and preventing crack propagation. These effects contribute to enhanced structural strength, making the concrete more capable of withstanding pressure. Conversely, a more significant decrease in compressive strength was observed with an increase in the PPF volume fraction. This reduction can be attributed to the inhomogeneous distribution of materials, challenges in dispersing the PPF in the mix, and the lower modulus of elasticity of these fibers.

Among all the mixtures tested, the 75 S-25P mixture achieved the highest average compressive strength, showing an increase of 59%, 51%, 53%, and 41% at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days, and 90 days respectively compared to the control mixture. This improvement can be attributed to the effect of the hybrid fibers, where StF contributes to increased compressive strength at all measured ages by providing structural reinforcement, while PPF helps reduce micro-cracks, promoting a more cohesive structure57. This synergistic effect of both fibers results in an overall improvement in the concrete’s performance. The 3 S mixture achieved the highest average compressive strength of the control mixture (without fibers), showing increases of 52%, 47%, 50%, and 38% at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days, and 90 days respectively. This is due to the fibers existence that evenly distributing the loads and preventing cracking, which improves the concrete’s ability to withstand pressure.

The 50 S-50P mix achieved lower average compressive strengths by 15%, 7%, 6%, and 8.5% at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days, and 90 days, respectively, compared to the 75 S-25P mix. Compared to the other mixes, the 50 S-50P mix exhibited a relatively lower average compressive strength at all measured ages. This can be attributed to the combination of StF, which enhanced compressive strength, and PPF, which helped reduce cracking, ultimately affecting the overall strength. Compared to the 50 S-50P mixture, the 25 S-75P mixture achieved an average compressive strength that was 9.2%, 13.3%, 7.7%, and 8.9% lower at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days, and 90 days respectively. This reduction is primarily due to the higher PPF content, which enhances flexibility and crack resistance but does not significantly improve compressive strength58.

Using of 3% PPF in the 3P mixture resulted in a decrease in compressive strength of 30.5%, 20.6%, 31% and 23% at 2 days, 7 days, 28 days and 90 days respectively, compared to the 3 S mixture. This decrease can be attributed to the limited effect of PPF on compressive strength, despite their benefits in improving resistance to cracking, fire, and shrinkage, which is consistent with previous research59.

The results for 90 days indicate significant variations between mixtures, with the 75 S-25P mixture achieving the highest compressive strength, while other mixes exhibited lower strength values due to the varying fiber contents. This section emphasizes the impact of fiber type and content on compressive strength at 90 days, in line with the primary focus on long-term performance, Overall, these findings highlight the influence of fiber type and content on the compressive strength of UHPC, with StF providing a more significant enhancement in strength compared to PPF.

Splitting tensile strengths

Figure 10 shows the average splitting tensile strength values for all mixtures at 2 days, 7 days, and 28 days. Tensile strengths ranged from 5.6 to 12.9 MPa at 2 days, from 7.5 to 15 at 7 days, and from 10.6 to 17 MPa at 28 days, which is consistent with previous studies60. The fiber-free control mix exhibited the lowest cracking resistance, with a strength of 10.6 MPa at 28 days. In contrast, the hybrid 75 S-25P mix, containing 75% StF and 25% PPF, achieved the highest strength of 17 MPa at 28 days. This represents about 89% improvement in splitting tensile strength over the fiber-free control mix at all ages. The observed increase is attributed to the complementary roles of the fibers: StF enhance stiffness and tensile strength, while PPF reduce microcracking and improve flexibility. The 3 S mix, containing 3% StF, showed a 5% increase in tensile strength at all ages compared to control, demonstrating StF’s effectiveness in distributing stresses evenly and limiting crack formation.

In the 50 S-50P mix, tensile strength was slightly decreased by 14.6% relative to the 75 S-25P mix, reflecting a balanced contribution from both fiber types. While this combination improved certain properties, the overall tensile enhancement was less pronounced than in mixes with higher StF content. Further reduction of StF to 25% and increasing PPF to 75% in the 25 S-75P mix led to an 8.12% decrease in tensile strength compared to the 50 S-50P mix. This reduction is due to the predominance of PPF, which enhance flexibility and crack resistance but provide less contribution to tensile strength61. Similarly, the 3P mix showed a 31.4% lower tensile strength at all ages compared to 3 S mix, highlighting that PPF, being less stiff than StF, are less effective in improving tensile performance. Previous studies indicate that single-grafted PPF concrete samples exhibit straight cracks along the loading line during testing, demonstrating brittle failure characteristics; while single-grafted StF concrete samples and hybrid fiber concrete samples exhibit fine branching cracks along the loading line, demonstrating ductile failure characteristics58.

As presented in Table 6, all mixtures showed a consistent increase in tensile strength over the curing period from 2 to 28 days. Notably, the most significant development occurred between 2 and 7 days, with strength increases ranging from 14% to 35%. This was followed by a moderate increase in tensile strength between 7 and 28 days, with improvements ranging from 10% to 32%. Among all the mixtures, mix 75 S-25P (12.9 → 15.0 → 17.0 MPa) and mix 3 S (12.7 → 14.5 → 16.0 MPa) exhibited the highest rate of strength gain, showing 28-day improvements of 32% and 26%, respectively. This trend highlights the enhanced crack-bridging efficiency of hybrid fibers as the curing process progresses, contributing to a denser microstructure that facilitates better stress transfer and improved overall strength62.

In contrast, mix 3P displayed the slowest early-age strength development (8.5 → 9.1 MPa, a 7% increase), but a more pronounced gain in strength at later ages, achieving a 40% increase by 28 days. This delayed improvement is likely attributed to the slower activation of the pozzolanic reaction and the relatively lower initial stiffness of the matrix. Overall, the results affirm that the splitting tensile strength of UHPC is highly age-dependent, with mixtures incorporating hybrid fibers showing the greatest strength growth, driven by superior fiber-matrix interactions and enhanced post-cracking resistance. This behavior reflects the enhanced crack-bridging efficiency of hybrid fibers at later ages as the matrix becomes denser and more capable of transferring stresses.

Flexural strength

In UHPC, flexural strength is strongly influenced by the content of StF and/or PPF. Figure 11 presents the average flexural tensile strength values for all mixes at 2, 7, and 28 days. The incorporation of StF and PPF significantly affected flexural tensile strength, with the lowest values observed in the mix containing only PPF, consistent with previous studies63. Among all tested mixes, the 75 S-25P mix exhibited the highest flexural strengths of 14.6, 23.4, and 30 MPa at 2, 7, and 28 days, respectively. This is consistent with previous studies showing that hybrid fibers significantly outperform monofilament fibers in both crack resistance and flexural stiffness64. In this combination, StF primarily enhanced bending resistance, while PPF contributed to crack mitigation and elasticity improvement. In contrast, the control mix recorded the lowest strengths, with values of 2.8, 3.4, and 5 MPa at the corresponding ages. The 3 S mixture, containing 3% StF, exhibited a six-fold increase in flexural strength at all ages compared to the control mixture. This improvement is attributed to the ability of StF to enhance concrete stiffness and structural integrity, thereby increasing resistance to bending under applied loads. Additionally, StF promotes more uniform load distribution, reducing crack formation and improving deformation resistance.

In the 50 S-50P mix, reducing StF content while increasing PPF caused a moderate decrease in flexural strength with average of 31% reduction at all ages compared to the 75 S-25P mix. This reflects the balance between stiffness and flexibility provided by the hybrid fibers. Similarly, in the 25 S-75P mix, further reduction of StF to 25% and increase of PPF to 75% led to an additional average of 40% reduction in flexural strength at all ages compared to the 50 S-50P mix. The higher PPF proportion contributes less to flexural strength relative to StF, resulting in reduced overall bending resistance. The 3P mix, containing only PPF, showed a more pronounced reduction in flexural strength at all ages compared to the 3StF mix, due to the lower structural rigidity of PPF.

These findings highlight the critical role of StF in enhancing UHPC bending resistance, while the combined use of StF and PPF provides a balanced improvement in mechanical performance under both static and dynamic loading conditions. This is consistent with the results of previous studies that showed that fiber blends with 20% plastic coarse aggregate and 20% SF performed excellently with improved mechanical and axial behavior and tensile strength56.

Modulus of elasticity

Figure 12 illustrates the average elastic modulus values measured for the each UHPC mix. As shown, the modulus of elasticity is influenced by fiber addition, increasing with higher StF volume fractions. This enhancement is mainly attributed to the inherently higher modulus of elasticity of StF. Among all mixes tested at 28 days, the 75 S-25P mix exhibited the highest modulus of elasticity at 45 GPa, while the control mix recorded the lowest at 30 GPa, consistent with previous studies65.

The inclusion of 3% StF in the 3 S mix resulted in a 17% increase in the modulus of elasticity compared to the control mix, consistent with the findings of Vivas et al.51. This improvement is attributed to the ability of StF to enhance the elastic response of the concrete and reduce deformations under high loads. Similarly, in the 75 S-25P mix, the modulus of elasticity increased by 19% compared to the control mix. Here, StF contributed to increased stiffness and resistance to deformation, while PPF enhanced elasticity and reduced cracking.

In the 50 S-50P mix, where the StF content was reduced to 50% and the PPF content increased to 50%, the modulus of elasticity decreased by 4.6% compared to the 75 S-25P mix. This reduction reflects the balance between stiffness and elasticity provided by the hybrid fibers. Similarly, in the 25 S-75P mix, with 25% StF and 75% PPF, the modulus of elasticity decreased by 7.3% compared to the 50 S-50P mix, primarily due to the predominance of PPF, which have a limited effect on stiffness relative to StF. In the 3P mix, the high proportion of PPF led to a significant 12% decrease in the modulus of elasticity compared to the 3 S mix. While PPF enhance elasticity and crack resistance, they do not provide the same stiffness as StF. These fibers improve internal load distribution, but their contribution is more pronounced in terms of increased elasticity rather than stiffness. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that the composition of hybrid fibers of different types, including steel, carbon fibers, and PPF, enhances these mechanical properties, providing a comprehensive approach to increasing tensile strength and durability66.

Fire resistance

A fire resistance test was conducted to evaluate the ability of UHPC to withstand elevated temperatures. Samples were exposed to various temperature conditions (200, 400, 600, and 800 °C) for a duration of 3 h to assess the impact of monofilament and hybrid fibers on the cementitious matrix. The test focused on evaluating the behavior of the concrete samples post-exposure, including crack formation, structural integrity, and overall performance, in order to determine the effects of heat exposure on the material’s durability and resilience. As shown in Table 6, the compressive strength results for the samples after heat exposure indicate that exposure to 200 °C led to a slight increase in compressive strength for all mixtures compared to the unexposure samples. This improvement can be attributed to the contribution of StF, which provide additional structural reinforcement and help mitigate micro-cracking, while PPF enhance fire resistance by facilitating the formation of vapor-venting channels, thus reducing internal pressure. Figure 14a confirms that no physical changes occurred on the surface of the cubes in any of the mixtures at this temperature.

As shown in Fig. 13, at 400 °C, a slight decrease in compressive strength was observed for all mixtures, indicating the initial deterioration of some cementitious bonds and the thermal softening of the fibers. StF mitigated this loss by maintaining internal load transfer. As confirmed by Fig. 14b,c, cracking and disintegration were particularly evident in the control mix, leading to the separation of outer layers of the cubes. At temperatures above 600 °C and 800 °C, severe fragmentation occurred, with large portions breaking off, especially at the edges of the specimens. Cubes reinforced with StF retained some mass due to the structural contribution of the fibers, whereas cubes containing only PPF disintegrated completely, highlighting the limited thermal stability of PPF. The color change from gray to brown and the partial retention of StF at 800 °C, as observed in Fig. 14e, indicate the gradual thermal deterioration of the concrete matrix.

Specifically, in the 3 S (3% StF) mixture, compressive strength increased by 11% at 200 °C, demonstrating the role of StF in enhancing the matrix and reducing cracking. As shown in Fig. 14a, no flaking or cracking was observed on the cube surfaces, indicating better preservation of their structural integrity. At 400 °C, compressive strength decreased by 25%, and exposure to temperatures of 600 °C and 800 °C led to disintegration, which can be attributed to the combined effects of thermal expansion, internal moisture, and partial decomposition of bonding phases. These findings are consistent with those reported by Liang et al.67.

In hybrid fiber blends, such as 75 S-25P, the synergistic effect of StF and PPF resulted in a slight increase in strength at 200 °C and mitigated the strength loss at 400 °C. However, at higher temperatures, surface fragmentation occurred, although internal cohesion with the fibers was maintained, as shown in Fig. 14d. In blends with a higher PPF content, such as 50 S-50P and 25 S-75P, a reduction in steel fiber content and an increase in PPF content led to a decrease in stiffness and thermal stability, causing greater strength loss, increased fragmentation, and complete surface disintegration at elevated temperatures. The 3P blend exhibited the most significant decrease in strength between 400 °C and 800 °C, where the PPF fibers melted and could no longer contribute to matrix reinforcement, resulting in complete disintegration, as observed in Fig. 14f.

Overall, these results confirm that the thermal performance of UHPC is strongly influenced by the type and size ratio of fibers, as illustrated in Fig. 13. StF primarily enhance structural integrity and resistance to large thermal cracks, while PPF offer secondary benefits by reducing micro-tears and mitigating internal vapor pressure. The combination of both fiber types improves performance at moderate temperatures. However, PPF alone is insufficient to maintain mechanical integrity at elevated temperatures, as its thermal stability is limited compared to StF.

Porosity

Figure 15 shows the results of the average measured porosity values for the UHPC mix at 28 days. The control mix (with no fibers) exhibited a porosity of 2.31%. The mix containing only StF had a porosity of 1.76%, while the mix with only PPF showed a porosity of 2.09%. The hybrid mixes displayed porosities ranging from 1.73% to 1.79%. As illustrated in Fig. 15, all fiber-reinforced mixes exhibited lower porosity compared to the control mix. Among all mixes, the 75 S-25P mix had the lowest average porosity, approximately 13.5% lower than the other mixes. This reduction is attributed to the StF that provides additional structural support and help to minimize air voids. In contrast, the control mix had the highest porosity, likely due to a greater number of air voids or a lower overall density.

The inclusion of fibers enhances the cohesion of the matrix components and reduces porosity, which is consistent with the compressive strength results discussed in “Compressive strength”. The StF, fine SCMs, and fine sand contribute to the formation of smaller and more uniform pores, thereby reducing the overall porosity of the cementitious matrix68. Low porosity in UHPC limits the penetration of water and other harmful agents. Vernet69 suggested that the overall porosity of UHPC should not exceed 1–2.5%, a conclusion supported by the results of this study. Furthermore, the observed pore sizes ranged from 2 to 10 nanometers. In general, the addition of StF significantly reduced UHPC porosity. Conversely, decreasing the proportion of StF while increasing the content of PPF led to higher porosity. This increase is attributed to several factors, including weak fiber matrix cohesion, leading to small gaps around the fibers, uneven fiber dispersion, and a weak interfacial transition zone (ITZ) around the PPF fibers. These factors increase porosity as matrix cohesion weakens22. Furthermore, the rheological effects of increased PPF content, such as changes in viscosity and flowability of the mixture, contribute to poor dispersion, further promoting pore formation70.

Impact resistance

Table 8 shows the detailed impact resistance results for all mixtures measured after 28 days, including initial cracking, final cracking, initial kinetic energy at cracking, and final kinetic energy at cracking. Figure 16 illustrates the impact resistance of all mixes for both initial and final cracking, showing that initial cracks ranged from 3 to 19, while final cracks ranged from 5 to 44. These results are consistent with previous studies51. As observed in Fig. 18c, the fracture pattern was small, triangular, and uniform in all directions of the sample, with a small pit at the point of impact of the steel ball. This behavior indicates the role of the fibers in dissipating kinetic energy during impact, thereby mitigating crack initiation. The presence of fibers leads to a redistribution of the applied load across the concrete matrix, enhancing its ability to absorb and disperse energy. This process reduces the extent of damage and improves the overall impact resistance of the material. This is consistent with previous studies reporting that hybrid fiber mixtures achieve the highest impact resistance71. As shown in Fig. 18, the fracture pattern was uniform, with a small pit at the point of steel ball impact. This indicates a consistent and effective distribution of impact forces, resulting in enhanced resistance to cracking.

Adding 3% StF to the 3 S mix resulted in a fivefold increase in initial crack resistance and a sevenfold increase in final crack resistance compared to the control mix, as evidenced by the fracture pattern in Fig. 18b, which closely resembles that of the 75 S-25P mix. Furthermore, the energy absorbed by the fibers helps to prevent rapid fragmentation of the concrete, enhancing its post-cracking behavior and overall impact resistance. This reinforces the structural integrity of the material by improving its ability to withstand and dissipate impact forces. The StF promote a more uniform load distribution, improving the concrete’s ability to resist impact-induced cracking. The 50 S-50P mix, containing an equal 50:50 volume blend of steel and PPF (3% total fiber content), exhibited a four-fold increase in initial cracking resistance and a 3.5-fold increase in final cracking resistance compared to the control mix. As observed in Fig. 18d, the post-fracture behavior of the specimen shows that the three-dimensional fracture pattern exhibits a wider propagation on one side and a narrower, deeper depression beneath the sphere on the other, indicating a change in the fracture pattern with varying fiber content. The StF blend enhances shock absorption, while the PPF mitigates the formation of micro-cracks, resulting in an optimal balance between stiffness and elasticity. This combination contributes to more consistent and improved impact resistance, enhancing the overall performance of the concrete.

In the 25 S-75P mix, where the StF content was reduced to 25% and the PPF content increased to 75%, the impact resistance increased three-fold in the initial cracking stage and 2.5-fold in the final cracking stage compared to the reference mix. The dominance of PPF in this mix enhances flexibility but results in lower overall impact resistance relative to mixes with higher StF content. As seen in Fig. 18e, the fracture pattern is characterized by a three-way split, with wider cracks and a smaller pit forming beneath the steel ball in the sample. This indicates a relatively lower impact resistance as the PPF content increases and the StF content decreases.

For the 3P mix, containing only 3% PPF, a slight increase in impact resistance was observed—approximately two-fold for the initial crack and 1.5-fold for the final crack—compared to the control mix. These fibers enhance flexibility, reduce initial cracking, and increase the concrete’s energy absorption capacity by promoting a more even distribution of stresses within the matrix. The post-fracture behavior of the sample, as observed in Fig. 18f, shows a regular fracture pattern similar to that of the control sample, with a semi-crater forming beneath the steel ball. This indicates that the impact resistance is lower compared to the hybrid fiber mixes.

Difference in number of blows

As shown in Fig. 17, the difference in number of blows between the initial and final cracks increases with higher StF content and decreases with higher PPF content. Among the mono-fiber blends, the 3 S mix showed the largest difference between initial and final cracks, with 9 blows, whereas the PPF blend showed a difference of only 2 blows compared to the control mix, consistent with the results of previous studies72. This improvement is attributed to the strong bond between the StF and the concrete matrix. In contrast, PPF fibers showed lower performance due to their weaker bond with the cement matrix, shorter length, and smoother surface, all of which contribute to reduced strength compared to StF. Although PPF fibers delayed fracture rather than fully preventing it, their ability to distribute stresses enhanced the concrete’s impact resistance.

Among all the mixes, the 75 S-25P blend showed the greatest difference, with 25 blows between initial and final cracks. This difference is primarily influenced by the tensile strength of the fibers. The 50 S-50P mix, with a maximum difference of 22 blows, demonstrated the most significant improvement overall. In contrast, the control mix exhibited brittle failure, with almost no difference between the number of blows required for initial and final cracks. The 25 S-75P mixture achieved up to four times better performance, thanks to the synergistic effect of StF and PPF. This combination not only enhanced the static mechanical properties but also substantially improved impact resistance, particularly during the initial cracking stage.

In general, StF and PPF contribute significantly to impact resistance by providing structural reinforcement to the concrete matrix. These fibers help dissipate kinetic energy during impact, thereby reducing crack formation. When the material is subjected to an external impact, the fibers help redistribute the applied load across the concrete, effectively absorbing and dispersing energy. As a result, the rate of crack initiation and propagation is slowed. Furthermore, the energy absorbed by the fibers prevents rapid fragmentation of the concrete, improving its post-cracking behavior and overall impact resistance.

Kinetic energy

Kinetic energy is a critical parameter for evaluating the material’s ability to absorb shocks and withstand mechanical stresses. The findings demonstrate how different fiber additions enhance the concrete’s capacity to resist impacts, providing valuable insights into improvements in its mechanical performance for applications requiring high impact resistance. Figure 19 shows the initial and final kinetic energy values for all mixes, reflecting the concrete’s energy absorption capacity. The initial kinetic energy ranged from 161.4 J to 1022 J, while the final kinetic energy ranged from 269 J to 2367 J, consistent with previous studies73. It is important to note that kinetic energy is directly proportional to the number of impacts, and all mixes exhibited consistent behavior during both initial and final cracking under static conditions.

Among the mixes, the 3 S and 75 S-25P blends recorded the highest values for both initial and final kinetic energy, with increases of 467%, 500%, 535%, and 780% compared to the control mix. This improvement is attributed to the presence of StF and PPF. StF contribute to the concrete’s durability and impact resistance by distributing stresses more evenly within the matrix. While PPF are less effective in resisting impacts, they enhance the concrete’s ductility and delay fracture, thereby improving stress distribution and reducing initial cracking, which results in greater energy absorption.

The 50 S-50P and 25 S-75P mixes also showed significant improvements in both initial and final kinetic energy, with increases of 435%, 360%, 300%, and 240% compared to the control mix. These enhancements are due to the fiber blend’s ability to increase the concrete’s energy absorption and reduce cracking. Specifically, the 50 S-50P and 25 S-75P mixes increased the initial cracking kinetic energy by factors of 5 and 4, respectively, compared to the control. Furthermore, the 3P mix improved the final cracking kinetic energy by a factor of 3, even with only 3% PPF. These fibers play a crucial role in enhancing stress distribution, increasing elasticity, delaying cracking, and absorbing more impact energy, thereby significantly improving the concrete’s overall impact resistance.

Water absorption

As shown in Fig. 20, the water absorption values for all UHPC mixes after 28 days of curing ranged from 0.602% to 0.922%, consistent with previous studies74. Among the tested blend, 75 S-25P exhibited the lowest average absorption at 22%, compared to all other fiber blends. This can be attributed to the presence of StF, which enhance internal bonding and reduce the formation of voids around the fibers. In contrast, the control mix displayed the highest absorption, although overall values remained very low due to the high density and compact microstructure of UHPC. Generally, the low absorption across all mixes is influenced by dense particle packing, low porosity, and the inclusion of fine materials such as MK and SF, which effectively fill micro voids and enhance durability.

The effect of PPF on water absorption becomes more pronounced when their proportion increases. The 50 S-50P mix showed a slight rise in absorption, approximately 20% higher than 75 S-25P mix, due to the flexible nature of PPF and their weaker bond with the matrix, which creates small pores around the fibers. In the 25 S-75P mix, the higher PPF content further increased absorption by about 31% compared to 75 S-25P mix, highlighting the reduced rigidity and adhesion of these fibers. Similarly, the 3P mix, containing only 3% PPF, exhibited the highest water absorption among fiber-reinforced mixes, as the exclusive use of flexible fibers generated microscopic voids within the matrix, slightly compromising compactness. Overall, these results demonstrate that while StF enhance matrix densification and reduce water ingress, increasing the proportion of PPF tends to slightly increase water absorption due to their lower stiffness and weaker interfacial bonding, this is consistent with the results of previous studies75.

Sorptivity

Sorptivity, which reflects the rate of water absorption, is a key indicator of concrete durability. In low-cement UHPC, the incorporation of hybrid fibers significantly influences the microstructure by bridging cracks and reducing porosity, thereby controlling water ingress. As shown in Fig. 21, mixes containing only StF or hybrid combinations generally exhibit lower average absorption rates compared to mixes with a high proportion of PPF. Specifically, the 25 S-75P mix recorded the highest absorption rate (3.4 mm), while the 75-25P mix showed the lowest rate (2 mm). At 28 days, the absorption evolution across all mixes ranged from 2 to 4.2 mm, aligning with the density results presented in Fig. 7. The control mix exhibited the highest and steadily increasing absorption, reflecting its more porous structure. Conversely, the 3 S mix reached saturation rapidly and remained stable, likely due to the effective synergy between StF and the cement matrix, which reduces porosity.

Mixes with higher PPF content, such as 25 S-75P and 3P, displayed similar absorption trends (3.2–3.4 mm), indicating increased porosity due to weaker interfacial bonding and micro void formation. Overall, StF enhance matrix density and limit microcrack development, thereby improving water resistance and the long-term durability of UHPC, while higher PPF content increases absorption and porosity.

A linear regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between permeability and absorption values for all mixtures, as shown in Fig. 22. As expected, a strong correlation was observed between permeability and absorption76. For example, the 75 S-25P mix exhibited the lowest porosity and sorptivity, further confirming the strong correlation between them.

Microstructural analysis

Figure 23 illustrates the micromorphology of fiber distribution in UHPC for non-fiber control mixes and mono- or hybrid fiber-reinforced mixes after 28 days of curing. The image reveals that both PPF and SF are randomly distributed within the matrix. The SF fibers are observed to be coarser, while the PPF fibers are finer. This distribution pattern underscores the distinct roles each fiber type plays in enhancing the overall performance of the concrete. SF fibers primarily provide structural reinforcement, improving the matrix’s tensile strength and crack resistance, whereas PPF fibers contribute to enhancing flexibility and mitigating micro-cracking, thus improving the material’s durability and post-cracking behavior.

The control mix displays a dense microstructure, where the substrate surrounding the aggregate is predominantly composed of a homogeneous hydrated calcium silicate (C–S-H) gel. Despite this dense formation, micro-cracks and small voids, attributed to shrinkage and the absence of reinforcement, were observed, as shown in Fig. 23a. These voids contribute to the high porosity of the mix, which aligns with the porosity results presented in Fig. 15. This observation highlights the importance of reinforcement in minimizing shrinkage and improving the overall structural integrity of the concrete, thereby reducing porosity and enhancing durability77. In contrast, the addition of 3% StF fibers to the 3 S blend, as shown in Fig. 23b, improves internal bonding, thereby improving the tensile strength and crack resistance of the base material, resulting in a more cohesive and homogeneous microstructure. This enhanced integrity aligns with the observed increase in compressive strength (Fig. 9), demonstrating the effectiveness of StF in reinforcing the UHPC matrix.

The predominant presence of StF fibers in the 75 S-25P and 50 S-50P mixtures leads to a denser microstructure, which effectively seals crack ends and prevents further crack propagation, as evidenced by the bending test results (Fig. 11). This behavior is consistent with previous studies57, which demonstrated the formation of a three-dimensional network structure formed by both SF and PPF, as shown in Fig. 23c,b. The enhanced crack-bridging and load-bearing capacity provided by the fiber network contributes significantly to the improved mechanical properties and durability of the mixture.

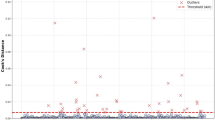

In the 25 S-75P mix, as depicted in Fig. 23e, the increased PPF content weakens the fiber-matrix adhesion, leading to the formation of additional microscopic voids. These voids reduce the effective compressive area of the matrix, which can potentially diminish its overall strength. However, despite the development of these micropores, the blend demonstrates an improvement in flexibility, as supported by the energy absorption results shown in Fig. 19. This suggests that the PPF enhance the material’s ability to absorb and dissipate energy, contributing to improved post-cracking performance, despite the potential drawbacks in terms of compressive strength. Similarly, the 3P mix shows pronounced micro voids around the fibers caused by weak fiber–matrix bonding, as shown in Fig. 23f. The high content of PPF, a hydrocarbon polymer, promotes a water layer at the interface, further weakening the bond and increasing porosity, which aligns with the higher water absorption observed in Fig. 1.

In general, all monofilament and hybrid fiber-reinforced mixes demonstrate superior performance compared to the control mix in terms of crack control and synergistic porosity enhancement. These mixes form a stable three-dimensional mesh structure, which significantly improves their ability to withstand external loads. The incorporation of fibers, whether monofilament or hybrid, contributes to enhanced structural integrity by effectively reducing crack formation and optimizing the distribution of internal stresses, thus improving the material’s durability and load-bearing capacity.

Life cycle assessment

The widespread use of cement in construction has raised serious environmental concerns, particularly regarding its contribution to global warming, as confirmed by both previous and recent studies26. The environmental impact of cement production is well-documented, given its high energy consumption and the significant carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions associated with its manufacturing process. Consequently, researchers have increasingly focused on strategies to reduce cement consumption and its associated environmental footprint by using environmentally friendly alternative materials, such as MK, fumed SF, QP, StF, and PPF. The use of these materials not only reduces reliance on cement but also contributes to the development of sustainable concrete solutions through the recycling of industrial solid waste. These additives have been shown to improve the overall performance of UHPC, enhancing its durability, mechanical properties, and longevity. Compared to a control mix without cementitious admixtures, the performance of these modified mixes was evaluated based on key indicators, including life-cycle cost, latent energy consumption, and CO2 emissions. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of using these materials was assessed, contributing to a more sustainable and economically viable alternative to conventional concrete. Table 9 summarizes the life-cycle costs, latent energy consumption, and CO2 emissions of the materials used in this study78,79. This comparison, based on previous research, highlights the environmental benefits of incorporating these admixtures into UHPC.

Cost efficiency

To determine the unit cost per mixture, the inventory data provided in Table 9, based on previous research80, was utilized, and the unit cost for each mixture was calculated using Eq. (6).

where, (C) represents the unit cost of the base material per cubic meter (USD/m3), while (Xi) denotes the unit cost (USD/kg) of material (i), with (n) ranging from 1 to 9, as outlined in Table 9. The weight of each material, (Yi), is provided in Table 4. Additionally, the standard cost per unit of compressive strength (USD/m3/MPa) was calculated using the compressive strength of each mixture after 28 days, expressed as the difference between the compressive strength and the total cost. The cost-effectiveness (kg/m3/MPa) of each material was estimated by dividing the compressive strength (MPa) at 28 days by the total actual cost of each mixture, as per Eq. (7).

This calculation offers valuable insights into the economic efficiency of each mixture in relation to its strength, providing key data for economic evaluation in construction applications.

Figure 24 illustrates that the use of cement with a content of 700 kg/m3 results in a lower production cost compared to the cement-based reference concrete18. Additionally, replacing StF with PPF led to a reduction in the cost per mix. Among the hybrid fiber mixes, the 50 S-50P and 25 S-75P mixtures exhibited higher cost efficiency and a lower environmental impact than the 3 S mix, thereby achieving an optimal balance between mechanical performance and environmental sustainability. Notably, the mix containing 3% 3PPF combined superior cost efficiency with a higher compressive strength than the control mix. Furthermore, it contributed to a reduction in the environmental impact associated with material storage and manufacturing due to its lighter weight. Overall, these findings confirm the economic viability of UHPC hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete systems by not only reducing fiber costs but also decreasing the demand for cement an ingredient known for its significant environmental footprint.

Energy efficiency

The effective energy (EE) of each mixture is calculated using Eq. (8), based on data from Table 9, as referenced from previous studies80.

In this equation, (EE) represents the effective energy of the mixture, (ei) denotes the unit effective energy of material (i), with (n) ranging from 1 to 9, as shown in Table 9. The variable (r) represents the weight of material (i), as detailed in Table 4. Additionally, the effective energy efficiency of each mixture, expressed as standard resistance (MPa/m³/MPa), is determined by using the compressive strength (MPa) of each mixture after 28 days of curing. The energy efficiency of each mixture is subsequently calculated using Eq. (9).

This calculation provides a comprehensive evaluation of energy consumption in relation to compressive strength, which is crucial for assessing the performance of the mixtures in terms of both their mechanical resistance and energy efficiency.

Figure 25 illustrates the energy efficiency of all mixes, ranging from 0.014 to 0.02 GJ/m3. The control mix demonstrates higher energy efficiency compared to the reference mix reported in previous studies18, thus highlighting the environmentally friendly nature of this study. Notably, all mixes containing hybrid fibers exhibit higher energy efficiency than the 3 S mix. This can be attributed to the lower energy requirement for the production of PPF compared to StF, making polypropylene a more sustainable option. These results suggest that incorporating a combination of two fiber types into a single mix is an effective strategy to enhance the energy efficiency of UHPC, thereby contributing to more sustainable construction practices.

Eco-efficiency

The production of UHPC is an energy-intensive process, primarily due to its higher cement content compared to conventional concrete. This process involves several energy-consuming steps, including crushing, grinding, and mixing, as well as the high temperatures required for cement production. Additionally, diesel fuel is used for the extraction and transportation of raw materials, further contributing to CO2 emissions. Previous studies, as referenced by Hills et al.81, have extensively documented the relationship between energy consumption and CO2 emissions. In contrast, materials such as sand, which have relatively low energy demand, result in significantly lower CO2 emissions when compared to cement and other cementitious materials. The emission factors for the base materials used in this study were derived from previous research, ensuring consistency in the CO2 emissions calculations for each concrete mix. CO2 emissions are calculated using Eq. (10).

where (Ci) represents the carbon dioxide emissions of each component (i) listed in Table 9, and (Wi) is the mass of the respective component, as detailed in Table 5.

To assess the environmental efficiency of UHPC, this study builds upon previous work by analyzing the environmental impact of each component in the concrete mix. Environmental efficiency is evaluated by considering the standard compressive strength of each mix at 28 days, along with the associated CO2 emissions, as outlined in Eq. (11).

As shown in Fig. 26, the control mix demonstrated the highest environmental efficiency compared to a reference mix from previous studies18. This confirms that reducing the cement content to 700 kg/m³ in UHPC contributes to an increase in environmental efficiency. Among all the fiber-reinforced mixes, the 75 S-25P, 50 S-50P, and 25 S-75P blends exhibited the highest environmental efficiency, highlighting the significant potential of combining PPF and StF as a sustainable alternative in UHPC, positioning it as a form of green concrete. Notably, the 3P mix outperformed the 3 S mix in terms of environmental efficiency. This can be attributed to the PPF, which enhance the concrete’s elasticity and crack resistance, thus improving its long-term sustainability. The incorporation of fibers contributes to the structural performance of the concrete, allowing for a reduction in binder material (e.g., cement), thereby lowering material consumption and mitigating environmental impact. These findings emphasize the importance of continuing to innovate in the integration of eco-friendly fibers and selecting locally sourced fibers to meet demand, ultimately advancing global sustainability objectives.

Conclusions

This study examined the influence of mono and hybrid fiber systems on the mechanical performance, durability characteristics, impact resistance, kinetic energy absorption, and microstructural behavior of UHPC produced with a reduced cement content. The research also aimed to develop an environmentally efficient UHPC mixture by minimizing cement usage while optimizing the reinforcement effect of hybrid steel and polypropylene fibers for advanced structural applications. Based on the experimental results and comprehensive analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

The addition of fibers led to a slight reduction in UHPC workability, with the lowest decrease observed in the 3 S mix (9.7%) and the highest in the 3P mix (11%) relative to the control. Nevertheless, all mixes maintained adequate workability for practical applications.

-

2.

The 3 S and 75 S-25P mixes exhibited superior mechanical performance. Compressive strengths reached 155 MPa and 152 MPa, tensile strengths 16 MPa and 17 MPa, and flexural strengths 28 MPa and 30 MPa at 28 days, respectively. These enhancements are attributed to the synergistic action of short fibers bridging microcracks and long fibers limiting macrocrack propagation.

-

3.

Hybrid fiber incorporation improved the elastic modulus of UHPC. Among single-fiber blends, 3 S mix showed the highest modulus, while 75 S-25P mix proved the most effective hybrid, achieving elastic moduli of 42.2 GPa and 43 GPa, respectively.

-

4.

The 75 S-25P mix achieved a compressive strength of 138 MPa at 28 days. Exposure to 200 °C increased strength by 11% due to drying effects, while at 400 °C, strength decreased by 25.2%. At 600 °C and 800 °C, deterioration of the concrete matrix occurred; however, PPF fibers effectively mitigated spalling and brittle failure, enhancing thermal resilience.

-

5.

Mixtures 3 S and 75 S-25P exhibited the highest impact resistance, with six-fold increases at the initial cracking stage and eight-fold at final failure. The control mixture demonstrated brittle behavior due to the absence of fibers. Hybrid fiber mixtures significantly improved both initial and final impact performance.

-

6.

The 75 S-25P blend displayed the greatest improvement in ductility and impact resistance, achieving a 44-blow difference between initial cracking and complete failure. In contrast, PPF alone provided limited contribution to impact resistance.

-

7.

The 75 S-25P and 3 S blends absorbed the highest kinetic energy, demonstrating that hybrid fibers effectively enhance UHPC toughness, impact resistance, and energy dissipation, while optimizing production efficiency and supporting practical engineering applications.

-

8.

SEM analysis revealed that higher StF content in the 3 S and 75 S-25P blends reduced porosity and strengthened the fiber–matrix interface. Increasing PPF content weakened the bond at the interface, leading to higher porosity and wider microcracks in hybrid UHPC.

-

9.

Hybrid fiber incorporation significantly enhanced UHPC durability. At 28 days, porosity decreased by 23.8% and 25%, water absorption by 30% and 34.7%, and capillary absorption was reduced by 2–2.4 mm (initial) and 2.4–2.6 mm (final) for 3 S and 75 S-25P mixes, respectively. These improvements result from reduced microcrack formation and limited water penetration, thereby ensuring long-term structural integrity.

-

10.

Sustainability analysis showed that the control and 3P mixes exhibited the highest level of sustainability among the tested mixes, making them a promising candidate for high-strength structural applications.

Overall, the study demonstrates that hybrid fiber reinforcement, particularly the 75 S-25P blend, offers an optimal balance of mechanical performance, impact resistance, thermal stability, and durability, establishing a strong basis for the development and engineering application of low-cement UHPC.

One of the main limitations of this study was the inability to fully control the uniform distribution of hybrid fibers within the concrete mix. This variation can impact the mechanical properties and long-term durability of concrete. Additionally, the long-term performance under real-world environmental exposures such as; freeze-thaw cycles, sulfate attack, and carbonation, requires further research to determine how these fibers affect the material over extended periods. Future studies should focus on the long-term evaluation of the proposed mixtures in real-world conditions. This includes assessing the effects of repeated loadings, variations in temperature, and exposure to aggressive chemicals like sulfates and chlorides, which could impact the durability and integrity of the concrete over time. In addition, future research should investigate the optimization of fiber ratios tailored to specific applications such as high-impact, high-strength, or earthquake-resistant concrete structures. This will not only enhance the material’s performance but also provide cost-effective solutions for various construction needs.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Kim, G. W. et al. Influence of hybrid reinforcement effects of fiber types on the mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 426, 135995 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. A review on ultra high performance concrete: part II. Hydration, microstructure and properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 96, 368–377 (2015).

Raza, M. U., Butt, F., Ahmad, F. & Waqas, R. M. Seismic safety assessment of buildings and perceptions of earthquake risk among communities in Mingora, Swat, Pakistan. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10 (4), 1–18 (2025).

Naidu, G. D. R., Gaddam, M. K. R., Maganti, T. R., Anurag, A. & Chowdary, L. Energy-efficient ternary blended alkali-activated hybrid fiber reinforced concrete with recycled aggregates and phase change materials. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 11 (1), 25 (2026).

Shi, C. et al. A review on ultra high performance concrete: part I. Raw materials and mixture design. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 741–751 (2015).

Shafieifar, M., Farzad, M. & Azizinamini, A. Experimental and numerical study on mechanical properties of ultra high performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 402–411 (2017).

Wang, X., Yu, R., Shui, Z., Song, Q. & Zhang, Z. Mix design and characteristics evaluation of an eco-friendly Ultra-High performance concrete incorporating recycled coral based materials. J. Clean. Prod. 165, 70–80 (2017).

Yang, R. et al. Low carbon design of an ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) incorporating phosphorous slag. J. Clean. Prod. 240, 118157 (2019).

Maganti, T. R. & Boddepalli, K. R. Mechanical and microstructural properties of sustainable ternary blended alkali-activated concrete. Next Sustain. 6, 100122 (2025).

John, V. M., Damineli, B. L., Quattrone, M. & Pileggi, R. G. Fillers in cementitious materials—Experience, recent advances and future potential. Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 65–78 (2018).

Lyu, X., Ahmed, T., Elchalakani, M., Yang, B. & Youssf, O. Influence of crumbed rubber inclusion on spalling, microstructure, and mechanical behaviour of UHPC exposed to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 403, 133174 (2023).

Habert, G., Denarié, E., Šajna, A. & Rossi, P. Lowering the global warming impact of bridge rehabilitations by using ultra high performance fibre reinforced concretes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 38, 1–11 (2013).

Lyu, X., Elchalakani, M., Ahmed, T., Sadakkathulla, M. A. & Youssf, O. Residual strength of steel fibre reinforced rubberised UHPC under elevated temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 76, 107173 (2023).

Zhong, R., Leng, Z. & Poon, C. Research and application of pervious concrete as a sustainable pavement material: A state-of-the-art and state-of-the-practice review. Constr. Build. Mater. 183, 544–553 (2018).

Ahmad, F., Qureshi, M. I., Rawat, S., Alkharisi, M. K. & Alturki, M. E-waste in concrete construction: recycling, applications, and impact on mechanical, durability, and thermal properties—a review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10 (6), 246 (2025).

Maganti, T. R. & Boddepalli, K. R. Optimization of mechanical and impact resistance of high strength glass fiber reinforced alkali activated concrete containing silica fume: an experimental and response surface methodology approach. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04343 (2025).

Yu, R., Spiesz, P. & Brouwers, H. J. H. Effect of nano-silica on the hydration and microstructure development of Ultra-High performance concrete (UHPC) with a low binder amount. Constr. Build. Mater. 65, 140–150 (2014).

Abdellatief, M. et al. Development of ultra-high-performance concrete with low environmental impact integrated with Metakaolin and industrial wastes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01724 (2023).

Ren, D. et al. Durability performances of wollastonite, tremolite and basalt fiber-reinforced Metakaolin geopolymer composites under sulfate and chloride attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 134, 56–66 (2017).

Su, Z., Guo, L., Zhang, Z. & Duan, P. Influence of different fibers on properties of thermal insulation composites based on geopolymer blended with glazed Hollow bead. Constr. Build. Mater. 203, 525–540 (2019).

Tahwia, A. M., Helal, K. A. & Youssf, O. Chopped basalt fiber-reinforced high-performance concrete: an experimental and analytical study. J. Compos. Sci. 7 (6), 250 (2023).

Dziomdziora, P. & Smarzewski, P. Effect of hybrid fiber compositions on mechanical properties and durability of ultra-high-performance concrete: A comprehensive review. Mater. (Basel). 18 (11), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18112426 (2025).

López-Buendía, A. M., Romero-Sánchez, M. D., Climent, V. & Guillem, C. Surface treated polypropylene (PP) fibres for reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 54, 29–35 (2013).

Yu, R., Tang, P., Spiesz, P. & Brouwers, H. J. H. A study of multiple effects of nano-silica and hybrid fibres on the properties of ultra-high performance fibre reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) incorporating waste bottom Ash (WBA). Constr. Build. Mater. 60, 98–110 (2014).

Smarzewski, P. & Barnat-Hunek, D. Property assessment of hybrid fiber-reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 16 (6), 593–606 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber high performance cement-based composites: mechanical properties, microscopic mechanisms, and carbon emission evaluation. J. CO2 Util. 93, 103039 (2025).

Yoo, D. Y. & Yoon, Y. S. A review on structural behavior, design, and application of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 10 (2), 125–142 (2016).

Ahmad, F. et al. Performance evaluation of cementitious composites incorporating nano graphite platelets as additive carbon material. Mater. (Basel). 15 (1), 290 (2021).

Way, R. & Wille, K. Material characterization of an ultra-high performance fibre-reinforced concrete under elevated temperature. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on UHPC and Nanotechnology for High Performance Construction Materials, 565–572 (2012).

Abid, M., Hou, X., Zheng, W. & Hussain, R. R. Effect of fibers on high-temperature mechanical behavior and microstructure of reactive powder concrete. Mater. (Basel). 12 (2), 329 (2019).

Hager, I., Mróz, K. & Tracz, T. Contribution of polypropylene fibres melting to permeability change in heated concrete-the fibre amount and length effect. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 12009 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Jabir, H. A. et al. Experimental tests and reliability analysis of the cracking impact resistance of Uhpfrc. Fibers 8 (12), 74 (2020).

Abid, S. R., Hussein, M. L. A., Ali, S. H. & Kazem, A. F. Suggested modified testing techniques to the ACI 544-R repeated drop-weight impact test. Constr. Build. Mater. 244, 118321 (2020).

Maganti, T. R. & Boddepalli, K. R. Synergistic enhancement of compressive strength and impact resistance in alkali-activated fiber-reinforced concrete through silica fume and hybrid fiber integration. Constr. Build. Mater. 471, 140702 (2025).

Limbachiya, M., Bostanci, S. C. & Kew, H. Suitability of BS EN 197-1 CEM II and CEM V cement for production of low carbon concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 71, 397–405 (2014).

A. S. For T. M. C. C.-9 on C. and C. Aggregates (ed), Standard Specification for Silica Fume Used in Cementitious Mixtures. ASTM International (2011).

Regalla, S. S. & Kumar, N. S. Optimizing ultra high-performance concrete (UHPC) mix proportions using technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) for enhanced performance: precision towards optimal concrete engineering. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04205 (2025).

Malik, U. J., Mohotti, D., Mo, H. & Lee, C. K. A global dataset of UHPC mix designs with supplementary cementitious materials and nano additives. Data Br. 112179 (2025).

Akhnoukh, A. K. & Buckhalter, C. Ultra-high-performance concrete: Constituents, mechanical properties, applications and current challenges. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15, e00559 (2021).