Abstract

High flow nasal cannula (HFNC) can reduce the need for intubation in patients with coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pneumonia induced acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF), but predictors of HFNC success could be characterized better. C-reactive protein (CRP) and D-dimer are associated with COVID-19 severity and progression. However, no one has evaluated the use of serial CRP and D-dimer ratios to predict HFNC success. We retrospectively studied 194 HFNC-treated patients admitted between August 2020 and October 2022. CRP and D-dimer levels relative to baseline at HFNC initiation were calculated up to three days thereafter. Intubated and non-intubated patient comparisons were assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test and t-test. Ninety-two patients were intubated and 102 were not. Median CRP ratios were lower in non-intubated versus intubated patients (0.69 v. 0.96, p = 0.050 for Day 1; 0.49 v. 0.61, p = 0.028 for Day 2; 0.33 v. 0.64, p = 0.008 for Day 3). D-dimer ratios did not change. CRP ratio monitoring in patients with AHRF due to COVID-19 within the first three days of HFNC application can serve as an objective adjunctive clinical tool to identify individuals who can continue to be supported with HFNC without escalating to invasive mechanical ventilation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia can develop acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) and acute respiratory distress syndrome1,2,3, a life-threatening pulmonary complication associated with high mortality3,4. Appropriate respiratory support for these patients during their hospital stay is therefore paramount to minimizing further disease progression and lung injury.

High flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is a respiratory support device that has filled the gap between conventional oxygen therapy and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). HFNC is widely used to manage COVID-19 patients5 and can reduce the need for IMV6 which, despite its life-saving potential, may induce lung injury and have lasting repercussions after discharge7,8,9,10. Conversely, HFNC use may delay intubation and worsen patient outcomes with acute respiratory failure11, and prolonged HFNC use prior to IMV has been identified as a risk factor for mortality in COVID-19-associated respiratory failure12,13. It would, therefore, be ideal to identify additional factors which may predict the success of HFNC near the time of initiation.

C-reactive protein (CRP) and D-dimer are routinely measured serum biomarkers whose elevations in COVID-19 patients are independently associated with adverse outcomes14. However, few studies have assessed the predictive value of these biomarkers for successful HFNC management in COVID-19 patients15,16,17, and none, to our knowledge, have evaluated the use of serial biomarker ratios in this respect.

Serial biomarker ratios may correlate with disease activity in a patient’s clinical course and can, therefore, be more informative in predicting HFNC success than a single measurement. This is particularly true for CRP, whose circulating levels are determined exclusively by its rate of synthesis in the liver—rising in response to the intensity of an inflammatory stimulus and decreasing in a first-order kinetic pattern with the removal of said stimulus18. Serial CRP ratios have been used to track the outcome of patients with ventilator-associated19 and community-acquired20 pneumonia in response to antibiotic therapy with ratios of 0.5 or more associated with poor outcomes. Similarly, studies with COVID-19 patients have used a 50% decrease in CRP levels within 48–72 h of treatment initiation as a marker of response to immunosuppressive21 and corticosteroid22 therapy.

In this study we evaluated the prognostic utility of serial CRP and D-dimer levels within the first three days of HFNC initiation to predict HFNC success in patients with AHRF as a result of COVID-19 pneumonia.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study reviewed electronic medical records for all consecutive adult (≥ 18 years of age) patients managed with HFNC for AHRF due to COVID-19 pneumonia within the Queen’s Medical Health System between August 2020 and October 2022. The Queen’s Health System consists of three main hospitals serving the state of Hawai’i: The Queen’s Medical Center (QMC) in urban Honolulu, QMC–West O’ahu, and North Hawai’i Community Hospital on the Big Island of Hawai’i. During the height of the COVID pandemic, The Queen’s Health System managed 60% of all COVID-19 related ICU care in the state of Hawai’i. COVID-19 was confirmed by SARS-CoV-2 detection via real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction from any respiratory sample. AHRF was confirmed by the admitting physician. Inclusion criteria included HFNC use for at least six hours and a HFNC protocol in place using the ROX index to guide intubation decisions (see Supplemental file). Exclusion criteria included (1) a do-not-intubate order, (2) AHRF not primarily due to COVID-19, (3) HFNC use for post-extubation respiratory failure, (4) missing CRP or D-dimer measurements near the time of HFNC initiation (Day 0), (5) HFNC use for less than six hours, (6) diagnosis of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), and (7) treatment with Tocilizumab or Baricitinib. The QMC institutional review board approved this study (protocol #RA2021-048) and waived the requirement for informed consent due to the study’s retrospective design. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Outcomes

CRP and D-dimer levels relative to baseline were calculated using concentrations from Day 0 and approximately 24 h (Day 1), 48 h (Day 2), and 72 h (Day 3) thereafter. HFNC success was defined as avoidance of endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. HFNC failure was defined as the need for endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation due to respiratory failure at any point during hospitalization despite management with HFNC, as determined by the discretion of a group of intensivists who used the institution’s HFNC protocol to guide intubation decisions (see Supplementary file).

HFNC

Oxygen via HFNC was delivered by one of four sources: Optiflow™ nasal high flow therapy (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand), Airvo™ flow therapy (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand), the Vyaire MaxVenturi Blender with Oxygen Sensor (Vyaire Medical, Mettawa, IL, USA), and the VOCSN critical care ventilator (React Health, Sarasota, Florida). Each source was applied continuously with a flow rate of 40 L/min and fraction of inspired oxygen of 1.0 at initiation, then subsequently titrated to maintain an oxygen saturation of at least 92%.

Data collection

Extracted medical record data included demographics, COVID-19 vaccination status, comorbidities, radiological findings, time to intubation, admission diagnosis, presenting symptoms and duration on arrival, medications, and laboratory measurements including serum CRP and D-dimer concentrations at Days 0, 1, 2, and 3.

Statistical analysis

Initial analyses described the study variables. Categorical variables are described by the number and percent of patients in each category and continuous variables are described by medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. The study outcomes were changes in CRP and D-dimer levels by day of follow-up relative to the patients’ baseline values. Percent changes from baseline were calculated for each patient, and the mean percentage change for each group (intubated and non-intubated) by day were presented along with their 95% confidence intervals. The statistical significance comparing intubated and non-intubated patients was assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test and by t-tests. For binary variables, statistical significance between groups was tested using Pearson’s Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test (if one or more cells was less than five). Analyses of percent changes from baseline followed the methodology published by Cui et al.22. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to assess the performance of biomarker ratios of all three days and included both intubated and non-intubated patients. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3 (cran.r-project.org).

Results

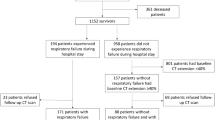

Of the 432 consecutive patients managed with HFNC for AHRF due to COVID-19 pneumonia between August 2020 and October 2022, 194 were included in the final analyses (Fig. 1).

Of these 194 patients, 47% (n = 92) were intubated (HFNC failure) and 53% (n = 102) were not (HFNC success) (Table 1). Patients in the two groups did not differ by age (median 61 v. 59 years, respectively; p = 0.175), gender (66% v. 60% males, respectively; p = 0.349), ethnicity, (p = 0.316), vaccination rate (18% v. 21%, respectively; p = 0.712), or treatment with remdesivir (76% v. 85% respectively; p = 0.103), and all patients in both groups were treated with dexamethasone. After patients with the initial exclusion criteria were excluded, there were 58 patients in the intubated group and 15 patients in the non-intubated group that were excluded due to DVT and PE. There were 10 patients in the intubated group and 18 patients in the non-intubated group who were treated with Baricitinib and were excluded. There were 10 patients in the intubated group and 5 patients in the non-intubated group who were treated with Tocilizumab and were excluded (Fig. 1). Among intubated patients, 43% (n = 40) identified as Asian, 45% (n = 41) as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHPI), and 12% (n = 11) as Non-Hispanic White while non-intubated patients were 34% Asian, 45% NHPI, and 18% Non-Hispanic White. However, compared to non-intubated patients, those in the intubated group had a 16% higher prevalence of hypertension (p = 0.020), and 12% lower prevalence of secondary pneumonia (p = 0.029). Intubated patients had significantly shorter hospital stays (median 12 v. 22 days; p < 0.001), fewer days on HFNC (1.7 v. 4.7; p < 0.001), and greater mortality (52% v. 0%; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

The median CRP ratio in the non-intubated group was lower than that of the intubated group for all three days: 0.69 v. 0.96 for Day 1 (p = 0.050), 0.49 v. 0.61 for Day 2 (p = 0.028), and 0.33 v. 0.64 (p = 0.008) for Day 3. In contrast, D-dimer ratios in either group did not change significantly (Table 2).

When expressed as a percent change from baseline, mean CRP levels in the non-intubated group decreased by 14% at Day 1, 38% at Day 2, and 50% at Day 3, with Day 2 and Day 3 being significantly different (p < 0.05) from CRP levels in the intubated group that conversely increased by 2%, 10%, and 4% at Day 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Fig. 2). The number of CRP values available for analysis at each time point is indicated in Fig. 2.

Using the same analysis, D-dimer levels showed inconsistent changes across time and differences never reached significance (data not shown).

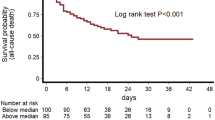

Construction of a ROC curve indicated that the overall accuracy of using the CRP ratio on Day 3 to determine whether patients on HFNC should be intubated was 75% (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we found that monitoring CRP ratios in patients managed with HFNC for AHRF due to COVID-19 pneumonia can be helpful within the first three days as an objective adjunctive clinical tool to identify individuals who can continue to be supported with HFNC. In contrast, monitoring D-dimer levels were not helpful. To our knowledge, we are the first to evaluate the use of serial CRP and D-dimer ratios in this respect.

Previous COVID-19 studies have assessed CRP as a predictive biomarker for HFNC effectiveness, reporting higher values in patients for whom oxygen therapy failed compared to those for whom it was successful15,16,17,23. Similarly, other studies have applied single CRP thresholds to predict the need for higher respiratory support24. Though important for triage purposes, the utility of such information for clinical care decisions is unclear.

Health care workers require prompt and objective criteria to guide intubation necessity, particularly for patients afflicted with serious respiratory conditions such as AHRF, which can cause rapid deterioration within a very short time. CRP levels reflect COVID-19 disease severity25,26,27 and successive CRP monitoring has been suggested as a way to predict a patient’s clinical course25. Mueller and colleagues reported serial CRP measurements in the first three days of a hospital stay to be more closely associated with clinical deterioration of COVID-19 patients than absolute levels at admission28. However, the CRP response is nonspecific29; it can be triggered by many factors unrelated to COVID-1930. Thus, to use serial CRP measurements in a prognostication capacity, it is essential to take into consideration baseline levels that are unaffected by confounding pathologies. Since this was not possible in our study due to its retrospective design, we employed serial CRP ratios (calculated in relation to baseline), which we viewed as a more pragmatic approach since patients served as their own controls. Doing so was especially important given the higher baseline CRP levels of the intubated versus non-intubated patients (median 86 v. 57 mg/mL, respectively, p = 0.003; data not shown), which may have been due to a combination of several medical, demographic, socioeconomic, and genetic factors that elicit a CRP response30. The significant decline in CRP ratios observed in non-intubated patients was supported by the mean CRP percentage change in this population, which was also significantly lower than the intubated group, particularly at Day 3 after HFNC initiation. Further, for Day 3 our ROC curve shows that the CRP ratio has a 75% probability of accurately identifying the need for intubation in patients currently on HFNC.

Similar to CRP, elevated D-dimer levels have been associated with COVID-19 disease severity31,32,33, and a number of studies have reported higher D-dimer admission levels in HFNC failure versus HFNC success patients17. As a degradation product generated after fibrinolysis, elevated D-dimer levels suggest a hypercoagulable or inflammatory state with vascular injury, and previous studies reported COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure to have severe hypercoagulability34,35. We excluded patients with DVT or PE, which commonly increase D-dimer levels36, and can also elevate CRP levels37,38, independently from inflammation associated with COVID infection. Patients with very high D-dimer levels frequently had DVT and/or PE, and including these patients would have affected the analysis. DVT and PE could also contribute to patients being intubated, independent of the severity of their COVID pneumonia and ARDS. Nonetheless, baseline D-dimer levels in intubated patients were higher than those in non-intubated patients with a trend towards significance (median 1.20 v. 0.90 ug/mL, respectively; p = 0.055, data not shown). However, these levels did not change significantly over the next three days in either the intubated or non-intubated groups (respectively from 1.05 to 0.79 at Day 1 to 1.06 and 0.94 at Day 2 to 1.23 and 0.96 at Day 3; data not shown). In a previous report with COVID-19 patients, D-dimer levels peaked ten days after admission39. Thus, it is possible that three days was too short a time period to monitor D-dimer changes. Further studies with longer monitoring periods are warranted to clarify this issue. D-dimer levels may have also remained elevated from non-COVID-19 conditions such as pregnancy, infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hypertension, and cancer35, or drug treatment. Previous studies40,41 reported increased D-dimer levels in COVID-19 patients treated with Tocilizumab, an immunosuppressive drug used for certain inflammatory conditions. However, opposite effects were reported in severe COVID cases treated with Baricitinib, an immune modulatory agent42. Further, both drugs have been associated with lower CRP levels and improved outcomes42,43,44; thus, use of these medications could reduce intubation rates and introduce confounding, and were, therefore, part of our exclusion criteria.

Intubated and non-intubated patients in our study were similar except for a few notable factors including the duration of hospital stay, which was significantly shorter in the intubated group and likely due to the higher mortality in this patient group. Mortality was zero in the non-intubated group since Do-Not-Intubate patients were excluded, and patients who were not doing well despite management with HFNC ended up in the intubated group. Also, the non-intubated group was managed with HFNC for significantly longer periods of time than the intubated group (4.7 v. 1.7 days, respectively; p < 0.001), which was not surprising given the non-intubated patients did not have a worsening clinical course that would have led to intubation.

We chose to evaluate CRP ratios up to Day 3 as that is a reasonable time point at which clinicians might make a decision to intubate a patient who is not clinically improving while on HFNC. Indeed, at Day 3, the CRP ratio in the non-intubated group was 0.33, significantly lower than 0.64 of the intubated group. In fact, non-intubated patients demonstrated significant decreases in CRP ratios as early as Day 2 compared to intubated patients, a crucial observation given a previous study11 that reported intubation within 48 h of initiation to be associated with lower overall mortality in the ICU compared to intubation after 48 h in patients for whom HFNC failed. Importantly, at Day 2 patients in the non-intubated group, but not those in the intubated group, exhibited a median CRP ratio less than 0.50, the threshold above which has been associated with poor outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated19 and community-acquired20 pneumonia.

Limitations

Our primary hypothesis was that higher biomarker levels correlated with higher levels of COVID-associated inflammation due to their association with disease severity25,26,27,31,32,33, and quantification of this inflammation using a biomarker ratio could indicate an improving inflammatory response, which may identify patients who could continue safely with HFNC without escalation to intubation. While our intent was to use biomarkers as surrogates for disease severity, this could not be clearly discriminated from treatment effect, and remains a study limitation. To reduce the potential for confounding, we excluded patients treated with Tocilizumab or Baritcinib and patients with DVT and/or PE for reasons stated in the discussion, which reduced our sample sizes as noted in the results section.

Secondly, our study objective was limited to patients with AHRF due to COVID-19 pneumonia, and some had missing biomarker measurements at some of the follow-up time points. The retrospective nature of our study meant that we relied on data that had already been collected and not acquired specifically for the study’s aim (to understand the course of a disease while allowing for variations in patient progression with their prescribed treatment) at the appropriate time intervals. For that reason, missing data were inevitable, and reflects variation in patient circumstances and clinical decisions, rather than oversights in study execution. Patients who were intubated had less available biomarker data, as some expired and some clinicians likely felt less inclined to check biomarkers after patients were intubated. Omitting all patients without complete CRP data on Days 1, 2, and 3 was not feasible as doing so would have compromised statistical power, and CRP ratios should be studied further in prospective studies, larger cohorts, and in non-COVID-19 patients. We also attempted to analyze lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin levels, but these biomarkers were checked in fewer patients, the timing of the blood draws were not always within 24 h of HFNC initiation, and most of these patients did not have follow-up levels at appropriate time intervals. Ang-2 and ICAM-1, which are biomarkers of endothelial injury, have been identified as predictors of mortality in COVID-19 associated ARDS45. Unfortunately, these levels were not measured, but biomarkers of endothelial and alveolar epithelial injury would be interesting to analyze in a prospective study.

Thirdly, the potential effect of prone positioning on biomarkers and outcomes could not be determined in our retrospective study. As per hospital protocol, all patients with COVID-associated pneumonia who were started on HFNC were encouraged to do awake self-proning. However, compliance with this activity was difficult to accurately quantitate retrospectively, and this is a limitation of our study. While the efficacy of awake self-proning to avert intubation is appealing in concept, the benefits remain controversial46,47. Prone positioning may theoretically alter biomarkers48, and it has been shown to decrease CRP at Day 7 in patients treated with Non-Invasive Ventilation49. However, the effect of prone positioning on CRP levels in COVID patients treated with HFNC has not been defined. But since we studied CRP ratios, and not just averaged values in each group, patients served as their own controls with regard to baseline biomarker levels. Thus, any potential benefits from prone positioning should have been reflected in changes in the serial CRP ratios, which we feel has prognostic value.

Lastly, data were drawn from a single medical system in Hawai’i, which limits its generalizability to other clinical settings and populations.

Despite these limitations, this study has notable strengths. First, CRP is a robust and routinely measured biomarker with a long half-life (19 h) with levels unaffected by food intake, and presents only negligible diurnal and seasonal variation50. Second, data were extracted over 2.2 years, a much longer time period than other retrospective COVID-19 HFNC studies, which used data from only a couple weeks16,24 to a few months15,23,51. Third, NHPI constituted a large proportion (45%) of our patients in both groups. These minority individuals have been disproportionally impacted by COVID-19 infection52 and, to the best of our knowledge, have not been studied with respect to HFNC use. Finally, nearly all patients were managed by the same core Pulmonary/Critical Care group using the same HFNC protocol guided by ROX index assessments, which was intended to minimize the variability in clinical decisions, including the need for intubation.

Future directions

Patients with Asian ancestry made up a higher percentage of the intubated group than the non-intubated group, through the difference was not significant. Disaggregation analysis was not possible due to small sample sizes within each subgroup. Future studies exploring different Asian subgroups may yield interesting findings. Some patients on HFNC for an extended time had an initial decrease in CRP and did not initially need to be intubated, but subsequently exhibited a rise in CRP and were intubated later in their hospital course. Investigating the predictive value for CRP throughout the hospital course could prove useful, as such biphasic responses in patients with community-acquired pneumonia53 have reported mortality rates of 33%. To that end, further studies should aim to evaluate serial CRP ratios in patients with other respiratory diseases managed by HFNC, such as community-acquired pneumonia, ventilator-associated pneumonia with post-extubation respiratory failure, and acute respiratory failure not due to COVID-19.

Conclusion

Monitoring CRP ratios in patients with AHRF due to COVID-19 within the first three days of HFNC application can serve as an objective adjunctive clinical tool to identify individuals who can continue to be supported with HFNC without escalating to invasive mechanical ventilation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Queen’s Health Systems, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of the Queen’s Health Systems.

References

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395 (10223), 497–506 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama 323 (11), 1061–1069 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 8(5), 475–481 (2020).

Bellani, G. et al. Epidemiology, patterns of Care, and mortality for patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 countries. Jama 315(8), 788–800 (2016).

Crimi, C., Pierucci, P., Renda, T., Pisani, L. & Carlucci, A. High-Flow nasal cannula and COVID-19: A clinical review. Respir Care. 67(2), 227–240 (2022).

Ospina-Tascón, G. A. et al. Effect of high-flow oxygen therapy vs conventional oxygen therapy on invasive mechanical ventilation and clinical recovery in patients with severe COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. Jama 326(21), 2161–2171 (2021).

Konsberg, Y. et al. Radiological appearance and lung function six months after invasive ventilation in ICU for COVID-19 pneumonia: An observational follow-up study. PloS One. 18(9), e0289603 (2023).

González, J. et al. Pulmonary function and radiologic features in survivors of critical COVID-19: A 3-Month prospective cohort. Chest 160(1), 187–198 (2021).

Cabo-Gambin, R. et al. Three to six months evolution of pulmonary function and radiological features in critical COVID-19 patients: A prospective cohort. Arch. Bronconeumol. 58, 59–62 (2022).

Butler, M. J. et al. Mechanical ventilation for COVID-19: Outcomes following discharge from inpatient treatment. PLoS One. 18(1), e0277498 (2023).

Kang, B. J. et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 41(4), 623–632 (2015).

López-Ramírez, V. Y., Sanabria-Rodríguez, O. O., Bottia-Córdoba, S. & Muñoz-Velandia, O. M. Delayed mechanical ventilation with prolonged high-flow nasal cannula exposure time as a risk factor for mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2. Intern. Emerg. Med. 18(2), 429–437 (2023).

Bime, C. et al. Delayed intubation associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure who fail heated and humified high flow nasal canula. BMC Anesthesiol. 23(1), 234 (2023).

Smilowitz, N. R. et al. C-reactive protein and clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Eur. Heart J. 42(23), 2270–2279 (2021).

Ma, X. H. et al. Factors associated with failure of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in patients with severe COVID-19: A retrospective case series. J. Int. Med. Res. 50(5), 3000605221103525 (2022).

Schmidt, F. et al. Predicting the effectiveness of high-flow oxygen therapy in COVID-19 patients: A single-centre observational study. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 54 (1), 12–17 (2022).

Xu, D. Y. et al. Effectiveness of the use of a high-flow nasal cannula to treat COVID-19 patients and risk factors for failure: a meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Respir Dis. 16, 17534666221091931 (2022).

Póvoa, P. & Salluh, J. I. Biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy in adult critically ill patients: A critical review. Ann. Intensive Care. 2 (1), 32 (2012).

Póvoa, P. et al. C-reactive protein as a marker of ventilator-associated pneumonia resolution: A pilot study. Eur. Respir J. 25(5), 804–812 (2005).

Coelho, L. M. et al. Patterns of c-reactive protein RATIO response in severe community-acquired pneumonia: A cohort study. Crit. Care. 16(2), R53 (2012).

Khurshid, S. et al. Early fall in C-Reactive Protein (CRP) level predicts response to Tocilizumab in rapidly progressing COVID-19: Experience in a single-arm Pakistani Center. Cureus 13 (11), e20031 (2021).

Cui, Z. et al. Early and significant reduction in C-Reactive protein levels after corticosteroid therapy is Associated with reduced mortality in patients with COVID-19. J. Hosp. Med. 16(3), 142–148 (2021).

Garner, O. et al. Predictors of failure of high flow nasal cannula failure in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19. Respir Med. 185, 106474 (2021).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Risk factors for mortality and respiratory support in Elderly patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 35(23), e223 (2020).

Tjendra, Y. et al. Predicting Disease Severity and Outcome in COVID-19 patients: a review of multiple biomarkers. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 144(12), 1465–1474 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. C-Reactive protein level may predict the risk of COVID-19 aggravation. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 7(5), ofaa153 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Plasma CRP level is positively associated with the severity of COVID-19. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 19 (1), 18 (2020).

Mueller, A. A. et al. Inflammatory biomarker Trends Predict Respiratory decline in COVID-19 patients. Cell. Rep. Med. 1 (8), 100144 (2020).

Pepys, M. B. CRP or not CRP? That is the question. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 25 (6), 1091–1094 (2005).

Kushner, I., Rzewnicki, D. & Samols, D. What does minor elevation of C-reactive protein signify? Am. J. Med. 119(2), 166e17–166e28 (2006).

Henry, B. M., de Oliveira, M. H. S., Benoit, S., Plebani, M. & Lippi, G. Hematologic, biochemical and immune biomarker abnormalities associated with severe illness and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 58(7), 1021–1028 (2020).

Lippi, G. & Favaloro, E. J. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A pooled analysis. Thromb. Haemost. 120(5), 876–878 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: A case control study. J. Intensive Care. 8, 49 (2020).

He, X. et al. The poor prognosis and influencing factors of high D-dimer levels for COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1830 (2021).

Lippi, G., Mullier, F. & Favaloro, E. J. D-dimer: old dogmas, new (COVID-19) tricks. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61(5), 841–850 (2023).

Brill-Edwards, P. & Lee, A. D-dimer testing in the diagnosis of acute venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Haemost. 82(2), 688–694 (1999).

Gremmel, T. et al. Soluble p-selectin, D-dimer, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein after acute deep vein thrombosis of the lower limb. J. Vasc Surg. 54(6 Suppl), 48s–55s (2011).

Unno, N. et al. Superficial thrombophlebitis of the lower limbs in patients with varicose veins. Surg. Today. 32(5), 397–401 (2002).

Li, J. et al. D-Dimer as a Prognostic Indicator in critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Leishenshan Hospital, Wuhan, China. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 600592 (2020).

Chan, K. H. et al. Tocilizumab and Thromboembolism in COVID-19: A Retrospective Hospital-based cohort analysis. Cureus 13 (5), e15208 (2021).

Price, C. C. et al. Tocilizumab Treatment for Cytokine Release Syndrome in hospitalized patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: Survival and clinical outcomes. Chest 158 (4), 1397–1408 (2020).

Thoms, B. L., Gosselin, J., Libman, B., Littenberg, B. & Budd, R. C. Efficacy of combination therapy with the JAK inhibitor Baricitinib in the treatment of COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 4(1), 42 (2022).

Rezaei Tolzali, M. M. et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in the treatment of COVID-19: An umbrella review. Rev. Med. Virol. 32(6), e2388 (2022).

Calderón-Ochoa, C. et al. Tocilizumab demonstrates superiority in decreasing C-reactive protein levels in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, compared to standard care treatment alone. Microbiol. Spectr. 12(6), e0249823 (2024).

Spadaro, S. et al. Markers of endothelial and epithelial pulmonary injury in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 ICU patients. Crit. Care. 25 (1), 74 (2021).

Alhazzani, W. et al. Effect of awake prone positioning on endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure: A randomized clinical trial. Jama 327(21), 2104–2113 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. The application of Awake-Prone Positioning among non-intubated patients with COVID-19-Related ARDS: A narrative review. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 817689 (2022).

Spadaro, S. et al. Prone positioning and molecular biomarkers in COVID and Non-COVID ARDS: a narrative review. J. Clin. Med. ;13(2). (2024).

Musso, G. et al. Mechanical power normalized to aerated lung predicts noninvasive ventilation failure and death and contributes to the benefits of proning in COVID-19 hypoxemic respiratory failure. Epma J. 14 (3), 1–39 (2023).

Plebani, M. Why C-reactive protein is one of the most requested tests in clinical laboratories? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61(9), 1540–1545 (2023).

Topp, G. et al. Biomarkers predictive of extubation and Survival of COVID-19 patients. Cureus 13(6), e15462 (2021).

Kaholokula, J. K., Samoa, R. A., Miyamoto, R. E. S., Palafox, N. & Daniels, S. A. COVID-19 special column: COVID-19 hits native hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities the hardest. Hawaii. J. Health Soc. Welf. 79 (5), 144–146 (2020).

Coelho, L. et al. Usefulness of C-reactive protein in monitoring the severe community-acquired pneumonia clinical course. Crit. Care. 11(4), R92 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Koichi Keitoku, MD, from the University of Hawaii Internal Medicine Residency Program for his assistance in data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Lung Association of Hawai’i and Leahi Fund Endowed Chair in Respiratory Health, and NIMHD (grant U54MD007601).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.I. and G.D. are the study investigators and guarantors, and contributed to the study concept and intellectual content; A.P. and G.Z. contributed to data acquisition and collection; J.F.L. contributed to drafting the manuscript and critical revisions, J.D. contributed to data analysis and data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The QMC institutional review board approved this study (protocol #RA2021-048) and waived the requirement for informed consent due to the study’s retrospective design.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, R., Pham, A., Zhang, G. et al. Serial biomarker measurements may be helpful to predict the successful application of high flow nasal cannula in COVID-19 pneumonia patients. Sci Rep 15, 756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85210-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85210-z