Abstract

As a key food production base, land use changes in the Jianghan Plain (JHP) significantly affect the surface landscape structure and ecological risks, posing challenges to food security. Assessing the ecological risk of the JHP, identifying its drivers, and predicting the risk trends under different scenarios can provide strategic support for ecological risk management and safeguarding food security in the JHP. In this study, the landscape ecological risk (LER) index was constructed by integrating landscape indices from 2000 to 2020, firstly analyzing its spatiotemporal characteristics, subsequently identifying the key influencing factors by using the GeoDetector model, and finally, simulating the risk changes under the four scenarios by using the Markov-PLUS model. The results showed that: (1) Cropland was the dominant land use, and the most significant decreases and increases occurred in cropland and built-up land, respectively. The primary land use conversion was cropland to built-up land and the interconversion of cropland and water body. (2) LER exhibited a trend of initially increasing and subsequently decreasing, and the risk levels were predominantly medium and higher. The spatial pattern was high in the southeast and low in the central and northern areas. (3) The spatiotemporal patterns of LER resulted from the combined effect of multiple factors and were mainly influenced by the natural environment, of which the NDVI was the first dominant factor. (4) The land use intensity was higher in the natural and economic development scenarios than in the cropland and ecological protection scenarios, and the predicted LER in 2030 was higher in the former than in the latter two. These findings are important for formulating scientific and reasonable land use planning and ecological risk management strategies to balance economic growth and ecological preservation and maintain food security and ecological sustainability in the JHP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecological risk pertains to the adverse effects of alterations in the natural environment or disruptions caused by human activities on ecosystem structure and function1,2. Land use/cover change (LUCC) is a significant manifestation of the interaction between humans and nature3,4,5,6, which can directly display landscape pattern characteristics and reflect regional ecological environment changes7,8,9. LUCC has been proven to be linked to land degradation10, biodiversity loss11,12, and reduced ecosystem services13, serving as an important factor inducing ecological risks and providing a crucial perspective for ecological risk research. Over the past 60 years, nearly 32% of the global land surface has experienced changes in land use14, which have profoundly changed the surface landscape, caused significant interference to ecosystem structure and function, led to a significant increase in ecological risks, and threatened the harmonious coexistence between humans and nature15,16,17. Therefore, evaluating ecological risks associated with LUCC has emerged as a pivotal concern that demands immediate attention to foster sustainable development.

There are two main models for ecological risk assessment18,19. The first model operates within the research framework of “risk source–risk receptor–risk impact,” assessing potential ecological risks by establishing an indicator system20. It primarily emphasizes environmental hazards stemming from pollutants. For example, this framework has been applied to evaluate the ecological risks posed by heavy metal pollution in the sediments of Lake Mainit in the Philippines21 and to create ecological risk maps for heavy metals in agricultural soils in Dhaka22. The second model relies on the landscape ecology theory, utilizing various landscape pattern indices to construct a landscape ecological risk (LER) index to characterize the distribution of risks23,24,25. It emphasizes the adverse ecological effects arising from the interaction between landscape patterns and ecological processes under external disturbances and exhibits significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity and scale effects18,19. Compared with the first model, LER assessment breaks through the limitation of characterizing regional risks with specific natural risks (such as heavy metal pollution) and can comprehensively evaluate various potential ecological threats and their cumulative risks26,27,28. In addition, LER is based on land use and is particularly well-suited for assessing ecological risks arising from LUCC.

LER is currently widely used in regional ecological risk assessment, and the research focuses on spatiotemporal distribution and influencing factors3,29,30,31. For example, Karimian et al.32 revealed the spatiotemporal characteristics of ecological risks in the Dongjiang River, they concluded that its spatial distribution has apparent spatial dependence. Gao et al.33 used multi-scale geographically weighted regression to reveal the ecological risk response to changes in terrain gradient. Liu et al.13 delineated ecological zones based on ecosystem services and LER. However, there are still some shortcomings in the research on LER: (1) Most research endeavors focus on ecologically fragile zones or regions with prevalent human activities, and less attention has been paid to areas where food production is the dominant function. The swift expansion of urban and suburban areas has resulted in the significant encroachment of land dedicated to agricultural production, causing drastic land use changes in the main food production areas. Accordingly, the ecological risk situation has changed, threatening the stable supply of food in the region. (2) The existing research on LER influencing factors mainly focuses on quantifying a single factor, lacking the quantification of the combined effect of multiple factors. The GeoDetector model (GDM) can quantify both the individual contribution of a single factor and the interplay between two factors in influencing the dependent variable. Few studies use GDM to quantify the contribution rate of factors to LER. (3) Previous research efforts have predominantly concentrated on assessing current ecological risks, with insufficient attention to forecasting future ecological risks. However, using high-precision models to simulate future land use and generate ecological risk maps can significantly aid in refining land use management strategies.

The Jianghan Plain (JHP) is a crucial commercial grain base in China, where rice, cotton, and oilseed rape are the primary crops cultivated. Due to the numerous lakes, aquaculture is more developed. However, during the early stages of its development, the JHP faced a notable challenge: a high population density relative to the available land resources34. There was a large-scale phenomenon of enclosing lakes for reclamation, which seriously damaged the eco-environment of the lakes and aggravated the ecological pressure. In recent years, land remediation and ecological protection policies have effectively restored the area and ecological functions of the lakes in the JHP. Additionally, the slowing population growth and the significant migration of rural residents for work have alleviated the tension between humans and land to a certain extent. However, despite these improvements, the ecological issues of the JHP have received insufficient attention, and there needs to be a more quantitative spatial representation regarding ecological risks. Based on this, this study takes JHP as the research object and uses multi-source data with the aim of (1) revealing the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of LER from 2000 to 2020, (2) quantifying the influencing factors of LER and (3) multi-scenario simulation of LER.

Study area and data sources

Study area

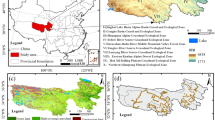

The JHP is located in the south-central part of Hubei Province, with a geographical location of 29°26′–31°54′ N, 111°14′–141°13′ E (Fig. 1). It covers 19 county-level administrative regions, including Jingzhou, Shashi, Jiangling, Gong’an, Jianli, Shishou, Honghu, Songzi, Xiantao, Tianmen, Qianjiang, Caidian, Hanchuan, Yingcheng, Shayang, Jingshan, Zhongxiang, Zhijiang, and Yicheng, with a land area of approximately 38,700 km2. Regarding natural conditions, JHP has a subtropical monsoon climate, which is suitable for growing rice, cotton, and other crops. JHP is rich in water resources, with the Yangtze River and the Hanjiang River running through the whole region, and there are more than 300 lakes, such as Honghu Lake and Changhu Lake. The regional terrain is flat, with an altitude of -5 ~ 1206 m and an average elevation of 61 m. The areas with higher altitudes are mainly Dahong Mountain in the northeast and the Western Hubei Mountains in the southwest. Regarding the social economy, in 2021, the GDP was 93.11 billion RMB, the total population was 12.99 million, and the urbanization rate was approximately 56.48%. Also, the total agricultural output value reached 203.36 billion RMB with a total sown area of 22.15 thousand hectares and a total crop output of 23.33 million tonnes.

Location of the Jianghan Plain. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

Data sources

This study used various raster and vector data, including land use, socioeconomic, and meteorological et al. (Table 1). All data were defined with the same projection and resolution (100 m), and data processing was performed in ArcGIS 10.7 and Python 2.7.

Methods

Study framework

The flow chart of this study is shown in Fig. 2, which mainly includes the following steps: (1) Based on the land use data and the divided risk evaluation unit, construct the LER evaluation model containing multiple landscape indices, spatially visualize the ecological risk of JHP from 2000 to 2020, and analyze its distribution pattern using spatial autocorrelation. (2) Select influencing factors from multiple dimensions and use GDM to detect the contribution of individual factors and the interaction of two factors to the spatial differentiation of LER. (3) A variety of development scenarios were designed, and the Markov-PLUS model was used to simulate land use changes under different scenarios and predict the spatial distribution of LER in 2030.

LER assessment

Division of LER assessment units

The scientific division of risk assessment units is essential in regional LER assessments and spatial visualization. The average patch area in the JHP in 2000–2020 is 2.14 km2, so a 3 km × 3 km grid was used based on the principle that a grid is 2 to 5 times the average patch area35. Finally, the JHP was divided into 4600 evaluation units using the Fishnet Tool of ArcGIS (Fig. 3), considering the region size, landscape spatial heterogeneity, and patch area.

Division of LER assessment units. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

LER index

This study constructed an LER index based on the area percentage of landscape types and the landscape loss index (LLI)28,36:

where LERk and Ak denotes the LER value and the total area of the k-th evaluation unit, respectively; N denotes the number of landscape; Aki and LLIki denotes the area and LLI of the i-th landscape in the k-th evaluation unit, respectively.

The LLI encompasses two key components: the Landscape Disturbance Index (LDI) and the Landscape Vulnerability Index (LVI). The LDI provides insight into the extent to which external disturbances impact various landscape while the LVI assesses the stability and resilience of these ecosystems in response to such disturbances. The calculation formulas are shown in Table 237,38,39,40.

First, the corresponding landscape index was calculated grid by grid using the Fragstats software, and then the LER value was calculated step by step according to the formula. Finally, the corresponding LER value was assigned to the center point of the risk assessment unit (Fig. 3), and the LER results were spatially visualized using the Ordinary Kriging (OK) interpolation in ArcGIS.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Spatial autocorrelation analysis is a statistical method for evaluating the spatial distribution patterns of variables by examining the relationship between their spatial locations and attribute similarities42. This study used spatial autocorrelation analysis in the GeoDa software to analyze the evolution of spatiotemporal patterns of LER in the JHP, including global and local spatial autocorrelation, and identified the spatial correlation of LER from global and local perspectives, respectively. The calculation formula is:

where Ig and Il are the global and local Moran index, respectively; n is the number of spatial units; xi and xj are the LER values of the i-th and j-th spatial units, respectively; \(\bar{x}\) is the average value of LER; Wij is the spatial weight matrix.

The GeoDetector model

GDM is an essential method for detecting spatial heterogeneity43,44. The method has two advantages: first, the factor detector can quantify the explanatory power of each factor, and second, the interaction detector can determine whether two factors have an interaction and its strength and type. The factor detector is calculated as follows44:

where q is the explanatory power, q∈[0, 1]; h is the stratification; Nh and N are the numbers of units in the layer h and the whole area, respectively; σ2h and σ2 are the Y-value variance of layer h and the whole region, respectively.

The interaction detector process was as follows: first, the q-values q(X1) and q(X2) were calculated for the single factor X1 and X2, respectively, according to Eq. (4); then, the q-values q(X1∩X2) were calculated for bi-variate interaction, and q(X1), q(X2) and q(X1∩X2) were compared.

This study selected 12 influencing factors (Fig. 4) from the natural environment (X1–X5), accessibility (X6–X9), and socio-economic dimensions (X10–X12). The GDM factor detector was used to measure the relationship and degree of influence between each factor and LER. The interaction detector analyzed the impacts of two factors together on the LER. The LER value for each grid calculated in Section “Division of LER assessment units” was selected as the dependent variable, the average value of each factor within the grid was used as the independent variable, and the “GD” package45 in R software was used to execute the GDM.

Markov-PLUS model

The Markov model can predict quantitative land-use changes, while the PLUS model can spatially simulate land use. By combining the strengths of both models, the coupled Markov-PLUS model can simulate changes in land use both spatially and temporally. This study has developed four scenarios to simulate land use in 2030 and predict the LER, which will serve as a reference for future ecological risk management.

Multi-scenario design

The Markov model is a stochastic process that describes the transition probability from one state to another46. The transfer probability matrix between multi-year land-use states can be used to predict future land use quantity. Modifying the transfer probability matrix makes it possible to predict land use demand under different scenarios. Based on the current land use situation in the JHP and related studies35,47,48,49,50, the following four scenarios were designed:

-

(1)

Natural development scenario (NDS): This scenario is based on the land use change pattern from 2010 to 2020. It does not consider the restrictive impact of any planning policy on land use change, keeps the transfer probability of each land use type unchanged, and uses the Markov model to predict the demand for each type of land use in 2030. This scenario is a reference scenario.

-

(2)

Economic development scenario (EDS): Based on NDS, this scenario emphasizes the importance of economic growth and the continuous growth of construction land. The conversion probability of cropland, woodland, grassland, water body, and unused land to built-up land increases by 20%, respectively. Spatially, the conversion of built-up land to other land types is prohibited.

-

(3)

Cropland protection scenario (CPS): This scenario emphasizes cropland protection to ensure food security. The conversion probability of cropland to built-up land is reduced by 30%, and the permanent basic farmland is used as a restricted layer. At the same time, considering that cropland occupied many water body from 2010 to 2020, the conversion of cropland to water body is restricted, and the transfer probability is reduced by 10%.

-

(4)

Ecological protection scenario (EPS): This scenario takes ecological environmental protection as the primary goal, restricts urbanization, and transforms land to a more natural state. The probability of woodland and grassland being transferred to built-up land and cropland is reduced by 20%, and the probability of water body being transferred to all land types is reduced by 20%. Spatially, the transfer of woodland, grassland, and water body is restricted, and the ecological red line is used as the restriction layer.

PLUS model

The PLUS model consists of two modules51: the land expansion analysis strategy (LEAS) and cellular automata based on multi-type random patch seeds (CARS). The LEAS module extracts LUCC data from two periods for sampling purposes. It employs the random forest algorithm to compute transition probabilities for various land types and determine driving factors’ contribution rates. On the other hand, the CARS module integrates random seed generation with a threshold decrement mechanism to simulate LUCC based on the calculated transition probabilities. For more details see the literate 51.

First, the 12 spatial variables (Fig. 4) and LUCC data were input into the LEAS to calculate the transition probability for each land use. Second, spatial changes in land use were simulated using the CARS by combining parameters such as the number of demands for each type predicted by the Markov model, neighborhood factors, and constraints.The change area for each land use was used to set the neighborhood weight parameters for the different scenarios52, with values in the range [0, 1], where higher values indicated greater expansion capacity for that land use type.

Spatial variables influencing LUCC in the Jianghan Plain. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

Results and analysis

The characteristics of LUCC

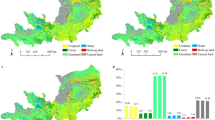

Regarding the composition and spatial distribution of different land use (Table 3; Fig. 5a), the dominant land use was cropland, which accounted for more than 63% and was widely distributed throughout the region. The second was woodland, which accounted for approximately 13% and was mainly distributed in the Dahong Mountains in the northeast and the Western Hubei Mountains in the southwest. Next was water body, which accounted for approximately 12%, mainly the Yangtze River, Hanjiang River, and Honghu Lake in the southeast. The percentage of built-up land was approximately 7%, which was more concentrated in Jingzhou, Caidian, Xiantao, and Zhongxiang. Grassland was small and scattered, and unused land was mainly distributed along the Yangtze River in Jianli, Shishou, and Honghu.

Regarding the land use transfer (Table 3; Fig. 5b), the main types from 2000 to 2010 were cropland to water body (1051.74 km2) and built-up land (429.65 km2). Except for cropland, which decreased by 1244.37 km2, the other increased to varying degrees, of which water body and built-up land increased by 828.48 km2 and 368.76 km2, respectively. From 2010 to 2020, the transfer accelerated, and the main types were water body to cropland (692.95 km2) and cropland to built-up land (628.25 km2). Except for cropland and built-up land, which increased by 130.76 km2 and 273.15 km2, respectively, the other decreased, among which water body and woodland decreased by 315.88 km2 and 76.83 km2, respectively. From 2000 to 2020, the leading types were cropland to built-up land (739.29 km2) and water body (694.31 km2). The cropland decreased by 1113.61 km2, while the built-up land and water body increased by 641.91 km2 and 512.60 km2, respectively.

LUCC in the Jianghan Plain. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

The spatiotemporal characteristics of LER

Spatiotemporal variation and transfer characteristics of LER

The LER values in 2000, 2010, and 2020 ranged from 0.195 to 0.735, 0.159 to 0.722, and 0.173 to 0.780, with mean values of 0.439, 0.442, and 0.441, respectively. Taking 2020 as the reference year, the LER was classified into five levels: lowest risk (LER < 0.325), lower risk (0.325 ≤ LER < 0.397), medium risk (0.397 ≤ LER < 0.447), higher risk (0.447 ≤ LER < 0.492), and highest risk (LER ≥ 0.492). The risk levels were mainly medium and high, with ecological risks that increased and then declined.

As shown from the distribution map of LER levels (Fig. 6a), the spatial patterns of LER were similar across the three periods of the JHP, with overall high values in the southeast and low values in the central and northern parts. The highest risk was mainly distributed in the southeast, where the land use was predominantly water. On the one hand, water body have high vulnerability; on the other hand, however, the area was mainly used for aquaculture with a high level of human intervention. Combined with a high landscape fragmentation, the highest ecological risk areas were clustered. A large cropland area was distributed in the central region, and the land use type mainly stayed the same for many years. However, many rural settlements were scattered throughout, resulting in a high landscape fragmentation, mainly manifested as medium risk. In the northern uplands, the land use type was dominated by woodland with a stable land use pattern and slight separation and fragmentation of patches. At the same time, there was a national forest park that was less exposed to anthropogenic disturbance and where the lowest ecological risk areas were clustered.

Difference analysis was performed on the LER map in different years (Fig. 6b–c). A negative value indicated risk reduction, a zero value indicated risk stabilization and a positive value indicated risk increase. From 2000 to 2010, the risk reduction zone was 2319.44 km2, mainly located in the significant urban expansion areas in the east and west. In these areas, the patch morphology tended to become regular after the original fragmentation, and the land use structure became more stable, leading to ecological risk reduction. The primary transfer types were from higher to medium risk (1286.77 km2) and medium to lower risk (509.29 km2). The risk increase zone was 3960.47 km2. These areas were mainly located in the southeast, where more agricultural land was converted into water body, leading to more significant landscape fragmentation. At the same time, water body ecosystems are fragile, and the ecological risk is elevated. The main conversion types were medium to higher risk (2019.55 km2) and higher to highest risk (1549.07 km2). During this period, the lowest, lower, and highest risk increased by 97.09 km2, 240.25 km2, and 1337.69 km2, respectively, while the medium and higher risk decreased by 1131.38 km2 and 543.65 km2 respectively, with an increasing overall trend in ecological risk.

From 2010 to 2020, the risk reduction zone was 3238.80 km2, with a higher concentration in the southeast. Land use in this zone mainly changed from water body to cropland, with increased landscape vulnerability and a risk decrease. The transfer types were mainly from higher to medium risk (1566.65 km2) and highest to higher risk (707.92 km2). The risk increase zone was 2728.99 km2 scattered throughout the region, with significant changes in land use type and anthropogenic disturbance leading to increased risk. The transfer types were mainly from medium to higher risk (1539.63 km2) and higher to highest risk (509.29 km2). During this period, the lowest and lower risk increased by 58.10 km2 and 302.34 km2, respectively, while the medium risk, higher risk, and highest risk decreased by 263.64 km2, 19.08 km2, and 77.72 km2, respectively, with a decreasing trend in ecological risk.

From 2000 to 2020, the risk reduction zone was 2527.97 km2, mainly east and west. The transfer types were mainly higher to medium risk (1066.11 km2) and medium to lower risk (807.50 km2). The risk increase zone was 3782.37 km2, mainly in the southeast. The transfer types were mainly from medium to higher risk (1880.94 km2) and higher to highest risk (1586.23 km2). During this period, the lowest risk, lower risk, and highest risk increased by 155.19 km2, 542.59 km2, and 1259.97 km2, respectively, while the medium and higher risk decreased by 1395.02 km2 and 562.73 km2, respectively, with an increasing trend in ecological risk.

Spatial distribution (a, b) and transfer (c) of LER in the Jianghan Plain. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

Spatial autocorrelation of LER

As shown in Fig. 7a, the global Moran index for LER in each year were 0.407, 0.431, and 0.391, respectively, which had significant spatial positive correlations (P < 0.05). This indicated that the LER was spatially aggregated, and the neighboring spatial units were similar, but the values and aggregation were low. The global Moran index increased and then declined, with an overall decreasing trend that reflected a weakening of the mutual influence of neighboring spatial units and a gradual decrease in spatial similarity.

Local spatial autocorrelation revealed the local space correlation pattern and identified the LER distribution for each spatial unit in its neighboring space. Figure 7b shows a similar spatial distribution pattern of LER in the JHP, and the spatial changes are relatively stable, both dominated by High-High and Low-Low. High-High were mainly distributed in the southeastern and central parts, where the land use was mainly water body with high risk. The number of spatial units increased and then decreased. Low-Low were mainly distributed in the southwest and north, with block-like aggregation in the north; land use was mainly woodland with low risk, and the number of spatial units increased and then decreased. Low-High and High-Low areas were fewer and more scattered, and both were distributed around High-High and Low-Low areas.

Moran index (a) and LISA cluster maps (b) for LER in the Jianghan Plain. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

Factors influencing LER spatiotemporal differentiation

Single factor detector

The single factor explanatory power quantifying of GDM and its variability over time is shown in Table 4. The q-values in 2000 were X5 > X2 > X8 > X1 > X4 > X12 > X11 > X3 > X7 > X9 > X10 > X6, and there were significant differences in the effects of each factor. The largest q-value for NDVI (0.3280) indicated that NDVI was the first dominant factor in the spatial differentiation of LER. The second dominant factor was slope with a q-value of 0.3192, followed by distance to rivers, elevation and average annual temperature. The distance to railways had the smallest q-value. In 2010 and 2020, the q-value ranking for elevation rose to third place, and there was little overall change in q-value ranking. Of the natural environmental factors, with the exception of annual precipitation, q-values for the other four factors were all in the top five and greater were than those for the accessibility and socioeconomic factors, indicating that the natural environment had the most significant influence on LER spatial distribution, with NDVI being the first dominant factor. All accessibility factors had weak influence, except for the distance to rivers, which had a higher q-value. Of the socioeconomic factors, population density had the most significant and increasing q-value, from 0.0990 in 2000 to 0.1429 in 2020, with a gradually increasing effect on LER.

Interaction detector

The interaction detector results reflecting the factors’ combined effect on LER (Fig. 8). For all three years, the interaction between any two factors was more influential than the impact of a single factor alone. The interaction types were mainly bi-linear and nonlinear enhancement, indicating that the spatial variability of LER in the JHP resulted from the combined effects of multiple influences. In 2000, the most vital interaction was X8∩X2, with a q-value of 0.5468. Other interactions with q-values greater than 0.5 included X8∩X5 (0.5316) and X8∩X1 (0.5035), and the q-values for other factor interactions were also significantly greater than those of single factors. The q-values of the main interactions increased in 2010 compared to 2000, with X8∩X2 being the largest (0.5475) and the q-values greater than 0.5 increasing to four. In 2020, X8∩X5 had the most significant q-value of 0.5314, followed by X8∩X2 (0.5184). The higher q-values for interactions X8∩X2, X8∩X5, X8∩X1, and X8∩X4 in each year significantly affected the LER spatial variability. In addition, the distance to rivers (X8) with each factor was much more significant than the interaction of other factor combinations.

Multi-scenario LER prediction

This study initially simulated the land use for 2020 and cross-checked it with actual data to validate the accuracy of the Markov-PLUS model. The resulting Kappa coefficient of 0.823 underscores a high confidence in the simulation, confirming that the model is reliable for predicting land use in the JHP53.

Future land use simulation

Table 5; Fig. 9 present the statistical data and distribution of land use for JHP in 2030, as predicted by the Markov-PLUS model. Under the NDS, the built-up land increased by 222.90 km2, mainly concentrated in Jingzhou, Xiantao, and Caidian. In contrast, woodland, grassland, water body, and unused land decreased by varying degrees. The water body declined considerably, with a decrease of 265.48 km2. Under the EDS, the increase in built-up land was more pronounced, with an increase of 362.40 km2, while cropland in the NDS first increased and decreased, and the water body coverage decreased the most (204.07 km2). Under the CPS, as a result of strict restrictions on the conversion of cropland to built-up land, only 162.09 km2 of land was expanded for construction, while cropland increased by 54.68 km2, and water body were protected, which slowed the rate of water body loss. Under the EPS, except for an increased built-up land, other decreased. Decreases in woodland and water body areas were the lowest of all four scenarios. The built-up land increased under all four scenarios, and the water body decreased under all four scenarios. The main conversion types were cropland to built-up land and water body to cropland.

Land use simulation in 2030. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

LER prediction

The statistics and spatial distribution of LER for different scenarios of JHP in 2030 are shown in Table 6; Fig. 10, respectively. LER values under the four scenarios of NDS, EDS, CPS, and EPS were 0.164–0.701, 0.179–0.741, 0.172–0.685, and 0.151–0.698, with mean values of 0.439, 0.441, 0.436 and 0.435, respectively. The risk levels were primarily medium and higher risks, and the spatial distributions were similar.

Regarding quantitative changes in LER (Table 6), under the NDS, the lower and medium risk decreased by 7392.32 km2 and 152.86 km2, respectively. In contrast, the higher, highest, and lower risk increased by 5189.65 km2, 2001.19 km2, and 354.34 km2, respectively. The EDS scenario results were the same as the NDS, with lower risk decreasing by 7440.83 km2 and higher risk increasing by 5061.92 km2. Under the CPS, the area of all classified areas increased, except for lower risk, which decreased by 7435.46 km2, and higher risk, which increased the most by 3882.79 km2. The EPS scenario results were the same as the CPS, with the lower risk decreased by 7452.09 km2 and the higher risk increasing by 3537.21 km2.

Regarding the spatial variability of LER (Fig. 10), there was little spatial variability across scenarios, with a high in the southeast and a low in the central and northern parts. Under the NDS, the risk reduction zone was 1030.98 km2, mainly around urban areas such as Jingzhou and Caidian. The risk increase zone was 2320.02 km2 and concentrated in Shishou, Jianli, and Honghu in the south. Under the EPS, the risk reduction zone was 980.46 km2, and the risk increase zone was 2839.46 km2, with a spatial distribution similar to the NDS. Under the CPS, the risk reduction zone was 2365.15 km2 and concentrated in Zhongxiang, Jingshan, and Tianmen in the north-central part of the city. The risk increase zone was 1650.81 km2 and concentrated in Caidian and Honghu in the southeast. Under the EPS, the risk reduction zone was 2749.03 km2. It was widely distributed throughout the region, with more prominent coverage in Shishou and Jianli in the south. The risk increase zone was 1614.51 km2, mainly in Honghu in the southeast.

A greater area was predicted to have increased risk under the NDS and EDS scenarios than decreased risk, with an upward trend. This was more pronounced under the EDS scenario with an increased pressure on ecosystems in the future. On the other hand, smaller areas under the CPS and EPS scenarios had increased risk than decreased risk, and there was an overall decrease in ecological risk. Risk under the EPS scenario decreased more significantly. The NDS and EPS scenarios had the highest and lowest ecological risks in the JHP in 2030.

LER prediction under different scenarios in 2030. Note Map was generated by ArcGIS 10.7.1 (https://www.esri.com).

Discussion

Impact of LUCC on LER

Different land use patterns show significant differences in LER due to human activities’ diversity and risk resistance capabilities. This study’s conclusions on LER of varying land uses are consistent with the results of previous related studies54,55. Specifically, cropland was mixed with many other landscapes, especially rural settlements. With inefficient land use and long-term farming, the ecosystem integrity and stability were affected, as well as a high landscape fragmentation and separation. The LER levels of cropland were mainly medium and higher (Fig. 11). In addition, cropland was the dominant land use type, resulting in an overall medium and higher LER in the JHP that significantly impacted the spatial distribution of LER. Woodland was clustered and distributed in the northeast and southwest. Stability and connectivity within woodland landscapes were high, losses due to external disturbance were low, and the woodland was mainly the lowest and lower LER, with the northeast and southwest areas having the most concentrated lowest and lower LER. Grassland was very small and mainly located around rivers and cropland. They were subject to greater natural and human disturbance, with a higher risk level. Water bodies and unused land were more sensitive to external disturbances, vulnerable than other landscapes, and had a high degree of loss56. These two land uses had the highest LER, which was mainly higher and highest risk, and the risk level for unused land was the highest. The continuous expansion of built-up land caused patches to become interconnected, primarily due to the internal expansion of urban land. Landscape fragmentation declined, landscape stability and connectivity increased, and the losses from external disturbance decreased. Urban land had a lower LER; urban expansion was usually the risk reduction area. The external expansion of urban land led to the fragmentation of edge areas. Hence, the risk was higher in the urban-rural interface zone, and the risk for rural construction land was higher than for urban land due to the fragmentation of patches and the landscape disturbance index. The overall risk of construction land was mainly medium.

Conversion between different land use types will directly lead to changes in LER57. Specifically, risk levels increase significantly when low-risk land types transition to high-risk ones. From 2000 to 2010, for example, the primary land use conversion types were cropland conversion to water bodies and cropland to built-up land. Compared with water bodies, cropland has fewer ecological risks. Therefore, the risk-increasing areas were concentrated southeast of Honghu Lake after large cropland was converted to water bodies. At the same time, the continuous expansion of urban areas such as Jingzhou and Caidian has occupied a large amount of cropland. Although the ecological risk within the expansion range decreased locally due to the transition of construction land, in general, the area of low-risk land use type converted to high-risk land use type during this period was more than the area of high-risk converted to low-risk, resulting in an overall increase in ecological risk. Conversely, when a high-risk land type changes to a low-risk one, the overall risk level decreases accordingly. From 2010 to 2020, for example, the primary land use conversion types included converting water bodies into cropland and cropland into built-up land. High-risk water bodies in the southeastern region have been converted into relatively low-risk cropland, resulting in the area’s concentration of ecological risk reduction areas. During this period, the area where high-risk land use types changed to low-risk land use types dominated the area more than where low-risk land use types changed to high-risk types. Therefore, the overall ecological risk showed a downward trend.

Drivers of LER

LER’s spatial distribution pattern results from natural and anthropogenic factors58. This study revealed that NDVI, slope, distance to rivers, elevation, and average annual temperature significantly affect the LER of JHP. Among them, NDVI is the first dominant factor of LER, and its spatial distribution shows a negative correlation with LER. This finding is consistent with the conclusion of Ai et al.41. NDVI is an effective indicator for measuring surface vegetation coverage and growth conditions. Areas with high NDVI values tend to have good vegetation coverage, complete ecosystem structures, and stable functions, so the ecological risks are relatively low. For example, the southeast and west of the study area exhibit high NDVI with low LER characteristics. On the contrary, areas dominated by water bodies have lower NDVI values and relatively higher LER. Topographic factors (elevation and slope) are fundamental to forming landscape patterns57. They significantly influence the spatial pattern of ecological risk by modulating hydrothermal conditions, which influence the distribution of other environmental variables and differences in the intensity of human activities. Accessibility factors such as transport distance can characterize the strength of human activities28, and in this study, distance to rivers had a larger q-value. This is mainly attributed to the fragility of the water body landscape and its high sensitivity to disturbance. As the study area’s primary water source for crop cultivation and irrigation, the rivers are subjected to strong anthropogenic disturbances in the surrounding areas, leading to significant fluctuations in ecological risk with river changes. Climate change has a particularly significant impact on ecological risk in climate-sensitive areas54. The average annual temperature of JHP decreases gradually from south to north, and the low-value areas are mainly concentrated in the northeast and south, which shows similarity with the topographic distribution characteristics and becomes a key factor influencing the change of ecological risk. Overall, the q-values for natural environmental factors were significantly higher than those for transport accessibility and socioeconomic factors. Natural environmental factors mainly influenced the spatial pattern of LER in the JHP.

Future LER prediction and control

Future regional development needs to focus on coordinating and achieving high-quality regional economic development that is based on protecting the natural environment. Of the four scenarios designed in this study, NDS and EDS represented a higher intensity of land use change than CPS and EPS. External disturbances exacerbated landscape fragmentation and reduced ecosystem stability, making the ecological risk increase areas greater than the risk-reduced area. In addition, the LER under the NDS and EDS scenarios was higher than under CPS and EPS. Considering the functional positioning of the study area, CPS and EPS were more suitable scenarios for the region’s future development, which will be less exposed to ecological risk and more conducive to maintaining food security.

(1) For higher and highest-risk areas, strengthen ecological monitoring, protection, and restoration, and reduce land use and human activity intensity. Reduce the disturbance and impacts on ecosystem structure, restore fragmented landscapes, and reduce risk. Fencing of lakes and creating fields should be prohibited for high-risk rivers, lakes, and other waters. The comprehensive management of major waterways should be strengthened, ecological river corridors should be established, and their ecological functions should be considered. (2) For medium-risk areas, strengthen regional land consolidation, increase surface vegetation cover, reduce landscape fragmentation, and improve ecosystem stability. Rural areas should accelerate the conversion of idle agricultural land, promote the consolidation of rural settlements, and improve the intensification and efficiency of rural land use. Urban areas should have reasonable layouts and expand orderly, strictly adhering to the red line of farmland protection and ecological protection. Urban development should proceed in a way that reduces damage to forest land, farmland, and other landscapes. (3) For lower and lowest-risk areas, vegetation cover is high, and forests are extensive, but they are primarily at high elevations and are challenging to restore ecologically after damage. In this zone, strict environmental protection policies should be implemented to limit development intensity and reduce the impact of human activities.

Limitations and future work

This study revealed the spatiotemporal distribution of LER, which is valuable for the ecological safety of JHP and future research. However, there are some limitations: (1) LER based on landscape index can reveal the risk status of the region. Based on the actual situation of JHP and with reference to relevant research, this study selected a 5 km grid to calculate the relevant landscape index to construct the LER. However, the landscape index has a noticeable scale effect, so subsequent research can start from multiple scales and select the optimal scale to construct LER. (2) This study reveals the impact of single and double factors on LER but does not consider the spatial non-stationarity of the factors. Therefore, the geographically weighted regression model can be used to analyze and visualize the spatial heterogeneity impact of each factor on LER. (3) The design of future development scenarios mainly refers to relevant research and lacks specific regional characteristics. Future research may consider using a system dynamics model to conduct more detailed designs of future development scenarios.

Conclusions

This study constructed a LER assessment model using land use data and landscape index. The spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and driving forces of LER were analyzed, and the LER pattern for 2030 was predicted in the JHP. The main conclusions were as follows:

-

(1)

Cropland was the dominant land use in the JHP. The cropland decreased from 2000 to 2020, and the built-up land increased significantly. The primary conversion was cropland to built-up land and the interconversion of cropland to water body.

-

(2)

LER exhibited a trend of initially increasing and subsequently decreasing, and the risk levels were predominantly medium and higher. The spatial pattern was high in the southeast and low in the central and northern areas. The primary transfer type in the three periods was higher to medium risk in the risk reduction zone, and the primary transfer type in the increasing risk area was medium to higher.

-

(3)

The explanatory power of each factor on LER varied significantly. The spatiotemporal patterns of LER were mainly influenced by natural environmental factors, of which NDVI was the primary factor. The interactions between two factors were greater than that of a single factor, and the spatiotemporal pattern of LER resulted from several factors’ joint action.

-

(4)

The intensity of land use change under NDS and EDS was greater than under CPS and EPS, and the LER predicted by the former two in 2030 was greater than the latter two. The NDS and EPS scenarios had the highest and lowest LER, respectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Masoudi, M., Vahedi, M. & Cerdà, A. Risk assessment of land degradation (RALDE) model. Land. Degrad. Dev. 32, 2861–2874 (2021).

Kumar, V. et al. A review of ecological risk assessment and associated health risks with heavy metals in sediment from India. Int. J. Sedim. Res. 35, 516–526 (2020).

Kang, L. et al. Landscape ecological risk evaluation and prediction under a wetland conservation scenario in the Sanjiang Plain based on land use/cover change. Ecol. Ind. 162, 112053 (2024).

Liu, H., Zhou, L. & Tang, D. Exploring the impact of urbanization on ecological quality in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River Urban agglomerations, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 29, 1276–1298 (2023).

Hui, E. C. M. & Bao, H. The logic behind conflicts in land acquisitions in contemporary China: a framework based upon game theory. Land. Use Policy. 30, 373–380 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s. J. Geog. Sci. 24, 195–210 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. Global projections of future urban land expansion under shared socioeconomic pathways. Nat. Commun. 11, 537 (2020).

Bren d’Amour, C. et al. Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 8939–8944 (2017).

Kalnay, E. & Cai, M. Impact of urbanization and land-use change on climate. Nature 423, 528–531 (2003).

Mirzabaev, A., Strokov, A. & Krasilnikov, P. The impact of land degradation on agricultural profits and implications for poverty reduction in Central Asia. Land. Use Policy. 126, 106530 (2023).

Gomes, E. et al. Future land-use changes and its impacts on terrestrial ecosystem services: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 781, 146716 (2021).

Donadio Linares, L. M. The awkward question: what baseline should be used to measure biodiversity loss? The role of history, biology and politics in setting up an objective and fair baseline for the international biodiversity regime. Environ. Sci. Policy. 135, 137–146 (2022).

Liu, H. & Tang, D. Ecological zoning and ecosystem management based on landscape ecological risk and ecosystem services: a case study in the Wuling Mountain Area. Ecol. Ind. 166, 112421 (2024).

Winkler, K., Fuchs, R., Rounsevell, M. & Herold, M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat. Commun. 12, 2501 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nat. Sustain. 3, 564–570 (2020).

Liu, H., Zhou, L. & Tang, D. Urban Expansion Simulation coupled with residential location selection and land acquisition bargaining: a case study of Wuhan Urban Development Zone, Central China’s Hubei Province. Sustainability 15, 290 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Integrating ecosystem services and landscape ecological risk into adaptive management: Insights from a western mountain-basin area, China. J. Environ. Manage. 281, 111817 (2021).

Peng, J., Dang, W., Liu, Y., Zong, M. & Hu, X. Review on landscape ecological risk assessment. Acta Geogr. Sin. 70, 664–677 (2015).

Cao, Q. et al. Multi-scenario simulation of landscape ecological risk probability to facilitate different decision-making preferences. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 325–335 (2019).

Landis, W. G. Twenty years before and hence; Ecological Risk Assessment at multiple scales with multiple stressors and multiple endpoints. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 9, 1317–1326 (2003).

Laudiño, F. A. R., Agtong, R. J. M., Jumawan, J. C., Fukuyama, M. & Elvira, M. V. Assessment of contamination and potential ecological risks of heavy metals in the bottom sediments of Lake Mainit, Philippines. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 15, 100443 (2024).

Hossain Bhuiyan, M. A., Karmaker, C., Bodrud-Doza, S., Rakib, M., Saha, B. B. & M. A. & Enrichment, sources and ecological risk mapping of heavy metals in agricultural soils of Dhaka district employing SOM, PMF and GIS methods. Chemosphere 263, 128339 (2021).

Wang, S., Tan, X. & Fan, F. Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment and Impact factor analysis of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 14, 4726 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Spatial-temporal pattern analysis of landscape ecological risk assessment based on land use/land cover change in Baishuijiang National nature reserve in Gansu Province, China. Ecol. Ind. 124, 107454 (2021).

Tan, L. et al. Evaluation of landscape ecological risk in key ecological functional zone of south–to–North Water Diversion Project, China. Ecol. Ind. 147, 109934 (2023).

Du, L., Dong, C., Kang, X., Qian, X. & Gu, L. Spatiotemporal evolution of land cover changes and landscape ecological risk assessment in the Yellow River Basin, 2015–2020. J. Environ. Manage. 332, 117149 (2023).

Ren, D. & Cao, A. Analysis of the heterogeneity of landscape risk evolution and driving factors based on a combined GeoDa and Geodetector model. Ecol. Ind. 144, 109568 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Spatial variations in the relationships between road network and landscape ecological risks in the highest forest coverage region of China. Ecol. Ind. 96, 392–403 (2019).

Wang, W., Wang, H. & Zhou, X. Ecological risk assessment of watershed economic zones on the landscape scale: a case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Reg. Envriron. Chang. 23, 105 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Exploring new methods for assessing landscape ecological risk in key basin. J. Clean. Prod. 461, 142633 (2024).

Wang, B., Ding, M., Li, S., Liu, L. & Ai, J. Assessment of landscape ecological risk for a cross-border basin: a case study of the Koshi River Basin, central Himalayas. Ecol. Ind. 117, 106621 (2020).

Karimian, H., Zou, W., Chen, Y., Xia, J. & Wang, Z. Landscape ecological risk assessment and driving factor analysis in Dongjiang river watershed. Chemosphere 307, 135835 (2022).

Gao, B. et al. Multi-scenario prediction of landscape ecological risk in the Sichuan-Yunnan ecological barrier based on terrain gradients. Land 11, 2079 (2022).

Tong, Q., Swallow, B., Zhang, L. & Zhang, J. The roles of risk aversion and climate-smart agriculture in climate risk management: evidence from rice production in the Jianghan Plain, China. Clim. Risk Manag. 26, 100199 (2019).

Lin, X. & Wang, Z. Landscape ecological risk assessment and its driving factors of multi-mountainous city. Ecol. Ind. 146, 109823 (2023).

Zhang, W., Chang, W., Zhu, Z. & Hui, Z. Landscape ecological risk assessment of Chinese coastal cities based on land use change. Appl. Geogr. 117, 102174 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. Landscape ecological risk analysis of subtropical vulnerable mountainous areas from a spatiotemporal perspective: insights from the Nanling Mountains of China. Ecol. Ind. 154, 110883 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal exploration of ecosystem service value, landscape ecological risk, and their interactive relationship in Hunan Province, Central-South China, over the past 30 years. Ecol. Ind. 156, 111066 (2023).

Cui, X. & Huang, L. Integrating ecosystem services and ecological risks for urban ecological zoning: a case study of Wuhan City, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 29, 1299–1377 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Lin, F. Study on comprehensive zoning of landscape ecological risk and ecosystem service value of tourist scenic spots with high landscape value. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 30, 58–76 (2023).

Ai, J. et al. Assessing the dynamic landscape ecological risk and its driving forces in an island city based on optimal spatial scales: Haitan Island, China. Ecol. Ind. 137, 108771 (2022).

Ke, X. et al. Urban ecological security evaluation and spatial correlation research-based on data analysis of 16 cities in Hubei Province of China. J. Clean. Prod. 311, 127613 (2021).

Wang, J., Zhang, T. & Fu, B. A measure of spatial stratified heterogeneity. Ecol. Ind. 67, 250–256 (2016).

Wang, J., Xu, C. & Geodetector Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 72, 116–134 (2017).

Song, Y., Wang, J., Ge, Y. & Xu, C. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of spatial data. GIScience Remote Sens. 57, 93–610 (2020).

Jokar Arsanjani, J., Helbich, M. & de Vaz, N. Spatiotemporal simulation of urban growth patterns using agent-based modeling: the case of Tehran. Cities 32, 33–42 (2013).

Peng, K., Jiang, W., Ling, Z., Hou, P. & Deng, Y. Evaluating the potential impacts of land use changes on ecosystem service value under multiple scenarios in support of SDG reporting: a case study of the Wuhan urban agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 307, 127321 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Lv, J., Wang, J. & Wu, Y. Scenario simulation of ecological risk based on land use/cover change – a case study of the Jinghe county, China. Ecol. Ind. 131, 108176 (2021).

Peng, K. et al. Simulating wetland changes under different scenarios based on integrating the random forest and CLUE-S models: a case study of Wuhan urban agglomeration. Ecol. Ind. 117, 106671 (2020).

Wang, P. et al. Study on driving factors of island ecosystem health and multi-scenario ecology simulation using ecological conservation and eco-friendly tourism for achieving sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 373, 123480 (2025).

Liang, X. et al. Understanding the drivers of sustainable land expansion using a patch-generating land use simulation (PLUS) model: a case study in Wuhan, China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 85, 101569 (2021).

Wang, B., Liao, J., Zhu, W. & Qiu, Q. The weight of neighborhood setting of the FLUS model based on a historical scenario: a case study of land use simulation of urban agglomeration of the Golden Triangle of Southern Fujian in 2030. Acta Ecol. Sinica. 39, 4284–4295 (2019).

Tang, D., Liu, H., Song, E. & Chang, S. Urban expansion simulation from the perspective of land acquisition-based on bargaining model and ant colony optimization. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 82, 101504 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Application of geographical detector and geographically weighted regression for assessing landscape ecological risk in the Irtysh River Basin, Central Asia. Ecol. Ind. 158, 111540 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Ecological risk assessment and prediction based on scale optimization–A case study of Nanning, a landscape garden city in China. Remote Sens. 15, 1304 (2023).

Ju, H. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns and modifiable areal unit problems of the landscape ecological risk in coastal areas: a case study of the Shandong Peninsula, China. J. Clean. Prod. 310, 127522 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Terrain gradient response of landscape ecological environment to land use and land cover change in the hilly watershed in South China. Ecol. Ind. 146, 109797 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Landscape ecological risk assessment under multiple indicators. Land 10, 739 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42367070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., manuscript writing, data analysis, result interpretation, data generation; L.Z., data analysis, data collection, language editing, content review; D.T., funding acquisition, content review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Zhou, L. & Tang, D. Driving force analysis and multi-scenario simulation of landscape ecological risk in the Jianghan Plain, China. Sci Rep 15, 1480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85738-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85738-0