Abstract

This study investigated whether honesty is a stable trait or varies depending on situational factors. Using a coin flip guessing paradigm with monetary rewards, 33 participants completed trials with rewards ranging from 0.01 to 3 yuan. Modeling of behavioral data showed individuals have varying “honesty thresholds” where they switch from honest to dishonest behavior. EEG analysis revealed increased P300 amplitude when resisting greater monetary temptation, and individuals with higher honesty thresholds had lower P300 amplitudes for the same rewards. A late positive component indicated greater cognitive conflict when the reward amount neared an individual’s honesty threshold. These findings challenge the conception of honesty as a stable trait, instead demonstrating it varies based on contextual factors like reward size. Computational modeling and EEG provide insight into the cognitive processes underlying contextual shifts in honest behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although honesty is valued according to almost all moral standards and religious systems in the world, dishonesty is widespread and can cause serious socioeconomic losses10,15,44. Previous studies on honesty have basically agreed that honesty is a stable individual trait that can be displayed in various situations. However, there are also different opinions about why individuals show honesty or deception. As the philosopher Russell said, “The reason why people have morality is that they are not tempted enough”. Is the reason that individuals exhibit honest behavior that they are not sufficiently tempted to exhibit dishonest behavior? That is, when we increase the external temptation to a certain level, will individuals exhibit less honesty or even dishonesty, violating their inner moral principles to obtain external benefits? Additionally, if increasing external temptation can make an individual dishonest, to what extent will it make an individual exhibit dishonesty? Furthermore, is the level of external temptation necessary to abandon moral principles and benefit from dishonesty the same in different individuals?

To address these questions, this study introduces the concept of the “honesty threshold.” The honesty threshold refers to the critical point at which an individual’s probability of choosing honesty versus deception reaches a balance when faced with external temptations. At this critical point, the likelihood of choosing honesty or deception is 50%, reflecting the maximum conflict between the individual’s internal moral principles and external temptations. The honesty threshold is not limited to monetary rewards but applies to any external incentives that may prompt an individual to choose honesty or deception, reflecting the individual’s moral baseline in a specific context. “Honesty” is a complex social characteristic of individuals. The present study predicted that honesty may not be a stable trait across situations, as previous studies assumed. Instead, individuals are predicted to have their own “honesty threshold”, exhibiting honest behavior in situations within the upper limit of their honesty threshold but exhibiting dishonest behavior in situations above the upper limit of their honesty threshold.

The conflict between honesty and material gain is a core feature of human society. In our daily life, we are often faced with the conflict between the temptation to violate moral standards to satisfy our own interests and the desire to maintain our own moral standards. When will people choose to be honest and when will they choose to cheat? What influences people’s decision-making? Many previous studies have attempted to answer this problem. Adam Smith believes that when there is an opportunity to cheat, individuals should carefully weigh the possible external losses against the possible gains to decide whether to cheat1. In contrast to Adam Smith, some researchers believe that the decision of deception is not determined by the external reward but by the internal reward mechanism. The intrinsic reward mechanism of individuals includes honesty. Generally, individuals think that they are honest and believe in it, so individuals try to maintain this intrinsic concept. However, when individuals have the opportunity to gain greater benefits through dishonest behavior, most individuals will still choose to cheat to gain benefits. Therefore, if the individual chooses to cheat and benefit, the individual’s self-concept will be negatively updated. How can this contradiction be solved? It is always difficult for individuals to choose between two competing ideas. Should they choose to maintain their self-concept (honesty) or cheat to gain benefits19? 25explained that when individuals are aware of their dishonest behavior, they will take certain actions (reclassifying and explaining facts and ignoring moral standards) to rationalize their dishonest behavior25 to solve the contradiction between them. In addition, some researchers try to explain why individuals show deception from a cognitive control aspect. Researchers believe that individual behavior will be controlled by the self and that starting self-control requires the consumption of limited cognitive resources, so the cognitive resources allocated to moral management will decrease; thus, the individual’s ability to monitor dishonest behavior will decrease2. Because cognitive control resources are consumed and reduced, individuals may not be aware of their cheating behavior at all. Some studies have found that individuals with lower self-control ability will have more dishonest behaviors7. Moreover, honesty may be influenced by situational factors, such as social norms and codes of conduct in the work environment24, which can either strengthen or weaken intrinsic motivations for honesty. Individual preferences for honesty, the magnitude of monetary rewards, and the interaction between the two have also been shown to predict honest behavior. Acute stress, however, does not significantly alter decision-making regarding honesty36. Nonetheless37, found that stress affects dishonest behavior differently depending on individuals’ moral inclinations: stress increases dishonesty among relatively dishonest individuals but makes relatively honest participants even more honest. Additionally, research has shown that self-deception is employed to maintain self-esteem and reflect self-worth21, and different emotional experiences may also influence dishonest behavior48.

Although the above related research on honesty and deception can predict, to some extent, when individuals will choose honesty or deception and the factors affecting people’s decision-making, it has overlooked the cognitive processes underlying dishonesty. In contrast to the above research, which has focused on how individuals reach the decision to behave dishonestly, research on the cognitive processes underlying dishonest behavior can improve understanding of the psychological processes accompanying dishonest behavior. Zuckerman et al. explained the psychological process of deception in detail for the first time in this study. This study thinks that deception mainly includes four influencing factors: control, arousal, affective and cognitive49. There are also studies showing that deception includes the process of mutual communication and two-way communication, which includes the function of social communication and uses executive cognitive resources6. Walczyk et al. tried to understand why truth-telling is inhibited while lies arise43. Mohamed et al. combined neural, cognitive and emotional processes to explain dishonest behavior and thought that the deception process can be divided into seven stages with different brain activation regions29.

In this study, the concept of “honesty threshold” originates from the research on individuals’ cognitive control mechanisms when facing moral decisions. It extends the traditional view that honesty is a fixed personality trait, proposing that honest behavior is actually a dynamic process influenced by situational factors, and that it varies between individuals. The theoretical origins of the honesty threshold are rooted in decision-making frameworks that weigh external and internal rewards, as well as cognitive and moral theories that explain the interaction between self-concept, temptation, and behavior. Specifically, the cost-benefit analysis by1 and the self-concept maintenance theory by25 provide key theoretical foundations. Allingham and Sandmo emphasized the external rewards and losses in decision-making, while Mazar et al. highlighted the conflict between maintaining the self-concept and yielding to dishonest behavior. The proposed theory of the “honesty threshold” in this study considers not only the external temptation individuals face in moral decision-making processes that involve maintaining their self-image but also the individual’s need to maintain their self-image and the individual differences in facing the same moral decisions. Compared to previous theories, which focus on either external or internal factors in isolation, this concept offers a more comprehensive perspective that better aligns with the psychological processes involved in real-life moral decision-making. It enriches existing theories. For example, an individual with a high honesty threshold may still adhere to moral standards when facing significant external temptations, while an individual with a lower threshold may be more likely to yield. This difference suggests that the honesty threshold is influenced by cognitive control ability, moral standards, and the external environment. Moreover, the honesty threshold framework aligns with cognitive control theory, which posits that dishonest behavior depends on the availability of cognitive resources2. When resources are depleted, individuals may find it more difficult to resist temptation and are more likely to exhibit dishonest behavior. The concept of the honesty threshold builds upon existing theoretical frameworks and serves as a bridge, extending Allingham and Sandmo’s rational decision-making model by introducing individual differences in moral resistance. It also complements self-concept theory, providing a measurable point that shows when external pressures may override internal moral beliefs.

With advances in the field of cognitive neuroscience and the introduction of some pioneering experimental paradigms, researchers have started to examine the neural mechanisms of honesty. Event-related potentials (ERPs), with components that can be used as a quantitative index of the cognitive processes of individuals, can be used in related research on advanced brain functions and play an important role in moral decision-making, honesty and other fields. The P300 reflects the advanced cognitive activity of the brain and is an objective index for assessing brain function and individual psychological processes. The amplitude of P300 is considered negatively correlated with the difficulty of tasks, and the cognitive workload of lying is greater22. Identifying dishonest behaviors of the disguised amnesia type also found that P300 in the dishonest group was significantly lower than that in the honest group, which also indicated that the deception task was more difficult than the honest behavior task31. In addition, researchers believe that the P300 component is sensitive to feedback values and is not affected by feedback titer18. Some studies suggest that late ERP components are related to advanced cognitive processing, and the prolonged duration of EEG components reflects the persistence of cognitive28. LPC components distributed in the anterior brain region are thought to be related to conflict resolution and inhibition control47. Many researchers have proven that LPC components reflect the process of conflict resolution9,45. This may indicate that in a social environment where individuals are expected to behave honestly, they experience a greater degree of cognitive conflict when they choose to cheat. Therefore, to prevent the discovery of dishonest behavior, individuals must engage more cognitive resources to detect and control their cheating behavior.

This study used behavioral modeling to explore whether there are differences in the degree of deception exhibited by individuals according to different monetary rewards. If differences are observed, we can construct a model of individual honesty that changes according to the level of monetary temptation based on behavioral data and then identify the individual honesty threshold, thus demonstrating that honesty is not a stable trait. Furthermore, combined with ERP technology, the computational model was tested, and the cognitive processes underlying honesty were explored. By comparing whether there are differences in P300 components when individuals resist the temptation of money under three different money conditions, whether there is any difference in P300 components of individuals with high and low honesty thresholds when resisting money temptation under the same money conditions in the three groups, and whether there are differences in LPC components evoked by decision-making when the participants are faced with the conflict between the temptation of money gains and the maintenance of their own moral principles, this paper studies the cognitive process of individual honesty. If there are differences in P300 components when facing different money temptations and LPC components when individuals make honest decisions, it will prove that the cognitive process of honesty may include at least two stages: resisting money temptations and making decisions. This suggests that the honesty threshold is not only a psychological construct but can also be measured through neural markers.

This study introduces the concept and theory of the “honesty threshold,” advancing research on moral behavior by providing a framework to quantify and predict individual differences in honest behavior. In practice, it can offer guidance for interventions aimed at promoting moral behavior in professional, educational, and social environments. For example, creating environments that reduce excessive temptations or providing resources that enhance cognitive control may help individuals maintain honesty even in challenging situations. Through behavioral modeling and ERP technology, the study explores individuals’ honesty decision-making processes under varying monetary temptation conditions. Unlike the traditional view that honesty is a stable individual trait, our research shows that honest behavior is a dynamic process influenced by both the intensity of external temptations and individual moral standards. By introducing the concept and theory of the “honesty threshold,” we not only deepen our understanding of honest behavior but also provide a new perspective on the cognitive processes involved in moral decision-making.

Results

Behavioral results

The degree of deception of individuals under different monetary temptation levels

A repeated measures one-way ANOVA was conducted on the number of correct trials reported by participants at five different monetary levels: 3 yuan, 2 yuan, 1 yuan, 0.1 yuan, and 0.01 yuan. The results indicated a significant difference in the degree of individual deception across different monetary levels, F (4, 29) = 6.060, p = .001, partial η² = 0.455.

Behavior modeling obtains individual honesty threshold

When an individual carries out the task of “guessing coins”, theoretically, the participants can guess half of all the trials correctly. Second, when all the participants perform the coin-flips task, if the participants guess correctly, regardless of whether they are honest or not, the participants will not report that they guess wrong. Therefore, for any participant, given any amount of money under five money levels, theoretically, the proportion of the number of trials reported by the participants to guess correctly will not be greater than or equal to 50%. For example, if an individual finally reports that 85% of all trials were right, this means that in half of all trials, the individual truly guessed and truthfully reported that he guessed right, and in the remaining half, 35% of the trials, the individual chose deception, and 15% of the trials, the individual chose honesty. Therefore, when an individual guesses the amount of money corresponding to 75% of the trials in the face of the report, it is the time when the individual has the greatest inner conflict; that is, under this amount of money, the individual has half the probability of choosing honesty and half the probability of choosing deception. Therefore, if we know that the participant has a 75% probability of reporting that he guessed the corresponding money correctly, the amount of money is the “honesty threshold” of the individual.

There are significant differences in the degree of deception of individuals under different money levels. Therefore, based on the collected behavior data, a model of the change in individual honesty with the level of money temptation is established, and the threshold of individual honesty is obtained. Based on the average number of guesses correctly reported by all participants at five money levels of 3 yuan, 2 yuan, 1 yuan, 0.1 yuan and 0.01 yuan, the threshold of individual honesty (The amount of money corresponding to the number of trials where the individual reports guessing correctly 75% of the time) was obtained by behavioral modeling (Fig. 1). The expression of the model is y = 1 −e −(\(\:\frac{x}{a}\))b+ C , where a and b together determine the form of the curve, and C represents the point where the participants’ report guessed correctly without any benefit. Each participant fitted the model based on their own data (Fig. 2; Table 1).

The model summarizes and reveals the general pattern of how an individual’s level of honesty changes in response to varying levels of monetary temptation. The results of the modeling indicate that honesty cannot be simply dichotomized. Whether an individual is honest or not is related to their own honesty threshold. When external monetary temptation exceeds an individual’s honesty threshold, the individual is more likely to engage in dishonest behavior. Conversely, when the external monetary temptation is below the individual’s honesty threshold, the individual is more likely to remain honest.

EEG results

Based on the difference wave between the maximum and minimum monetary temptation conditions (Fig. 3), six electrode positions were selected for statistical analysis in the time window of 470–550 ms after stimulus presentation: P1, P3, P5, P2, P4, and P6. Among them, the electrodes P1, P3, and P5 were combined and averaged together, and the electrodes P2, P4, and P6 were combined and averaged together for separate statistical analysis.

Results and analysis of EEG data within the same individuals under different monetary temptation levels

The average amplitudes of the P1, P3 and P5 electrodes and the P2, P4 and P6 electrodes were added and averaged together in the time window of 470–550 ms after stimulation, and the single-factor RM-ANOVA was performed.

The average amplitudes of the P1, P3, and P5 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together. The difference within the same participants in terms of resistance of different monetary temptations was very significant, F (2, 26)= 17.219, p < .001, partial η² = 0.570 (Fig. 4a). Multiple comparisons revealed that the P300 amplitude within the same participants resisting 3 yuan was significantly higher than that induced by 0.01 yuan, p < .001 (Mresisting 3 yuan temptation = 466.174 ± 209.444 µV, Mresisting 0.01 yuan temptation = 272.228 ± 329.378 µV). The P300 amplitude within the same person induced by resisting the temptation of 3 yuan was significantly higher than that induced by resisting the temptation of 2 yuan, p = .002 (Mresisting 3 yuan temptation = 466.174 ± 209.444 µV, Mresisting 2 yuan temptation = 379.917 ± 211.180 µV). The P300 amplitude within the same person when resisting 2 yuan was significantly higher than that when resisting 0.01 yuan, p = .037 (Mresisting 2 yuan temptation = 379.917 ± 211.180 µV, Mresisting 0.01 yuan temptation = 272.228 ± 329.378 µV).

The average amplitudes of the P2, P4, and P6 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together. The difference within the same person when resisting different monetary temptations was very significant, F (2, 26) = 28.959, p < .001, partial η² = 0.690 (Fig. 4b). Multiple comparisons revealed that the P300 amplitude within the same person resisting 3 yuan temptation was significantly higher than that induced by resisting 0.01 yuan temptation, P < .001 (Mresisting 3 yuan temptation = 511.580 ± 269.781 µV, Mresisting 0.01 yuan temptation = 323.249 ± 346.978 µV). The P300 amplitude within the same person induced by resisting the temptation of 3 yuan was significantly higher than that induced by resisting the temptation of 2 yuan, P < .001 (Mresisting 3 yuan temptation = 511.580 ± 269.781 µV, Mresisting 2 yuan temptation = 400.551 ± 263.695 µV). There was no significant difference in the P300 amplitude within the same person when resisting 2 yuan and resisting 0.01 yuan, P = .151 (Mresisting 2 yuan temptation = 400.551 ± 263.695 µV, Mresisting 0.01 yuan temptation = 323.249 ± 346.978 µV).

In the time window of 470–550 ms, the average amplitudes of the P1, P3, and P5 electrodes were combined and averaged, as were those of the P2, P4, and P6 electrodes. The results showed that for the same individual, the greater the monetary temptation resisted, the larger the induced P300 component. Conversely, the smaller the monetary temptation resisted, the smaller the induced P300 component. The P300 induced when resisting a 3 yuan temptation was larger than the P300 induced when resisting a 2 yuan temptation, which in turn was larger than the P300 induced when resisting a 0.01 yuan temptation. (Fig. 5).

Results and analysis of EEG data in individuals with different honesty thresholds resisting the same monetary temptation

The average amplitudes of the P1, P3 and P5 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together, and the average amplitudes of the P2, P4 and P6 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together for independent-sample t tests.

The average amplitudes of the P1, P3 and P5 electrodes were added together in the time window of 470–550 ms. The results showed that when resisting the monetary temptation of 2 yuan, the P300 amplitudes induced by individuals with low honesty thresholds were significantly higher than those induced by individuals with high honesty thresholds, t(26) = 2.097, p = .046, Cohen’s d = 0.823, (Mlow threshold = 458.805 ± 219.685 µV, Mhigh threshold = 301.029 ± 175.952 µV) (Fig. 6a). When resisting the monetary temptation of 3 yuan, the P300 amplitudes induced by individuals with low honesty thresholds were significantly higher than those induced by individuals with high honesty thresholds, t(26) = 2.125, p = 0.043, Cohen’s d = 0.833, (Mlow threshold = 545.289 ± 228.807 µV, Mhigh threshold = 387.059 ± 158.977 µV) (Fig. 6b).When resisting the temptation of 0.01 yuan, there was no significant difference in the P300 amplitude between individuals with low honesty thresholds and individuals with high honesty thresholds, t(26) = 0.751, p = 0.459, Cohen’s d = 0.295, (Mlow threshold = 319.348 ± 410.244 µV, Mhigh threshold = 225.108 ± 228.565 µV).

The average amplitudes of the P2, P4 and P6 electrodes were added together in the time window of 470–550 ms. The results showed that when resisting the 2 yuan monetary temptation, the P300 component induced in low-threshold individuals was significantly larger than that in high-threshold individuals, t(26) = 2.786, p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 1.093, (Mlow threshold = 524.709 ± 190.189 µV, Mhigh threshold =276.394 ± 273.945 µV) (Fig. 6c). The P300 amplitudes in individuals with low honesty thresholds were significantly higher than those in individuals with high honesty thresholds When resisting the temptation of 3 yuan, t (26) = 2.098, p = 0.046, Cohen’s d = 0.823, (Mlow threshold = 612.398 ± 240.293 µV, Mhigh threshold = 410.763 ± 267.450 µV) (Fig. 6d). When resisting the temptation of 0.01 yuan, there was no significant difference in the P300 amplitude between individuals with low honesty thresholds and individuals with high honesty thresholds, t(26) = 1.153, p = 0.259, Cohen’s d = 0.452, (Mlow threshold = 398.415 ± 382.215 µV, Mhigh threshold = 248.083 ± 302.971 µV).

In the time window of 470–550 ms, the average amplitudes of the P1, P3 and P5 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together, and the average amplitudes of the P2, P4 and P6 electrodes were superimposed and averaged together. The results show that when different people resisted the same monetary temptation, the higher their individual honesty threshold was, the smaller the P300 amplitude induced.

Results and analysis of the decision-making phase

According to the hypothesis, when the external monetary temptation is closer to an individual’s honesty threshold, the greater the internal conflict the individual experiences. Based on Table 1, the difference between the individual’s honesty threshold and the five monetary temptation values can be calculated. The smaller the difference between the two values, the greater the internal conflict of the individual. This allows us to determine the monetary amounts that cause the greatest and smallest internal conflicts when the participant faces external monetary temptations, thus identifying the group with the maximum conflict and the group with the minimum conflict.

The ERP waveforms were time-locked to the onset of the “heads or tails” stimulus presented on the decision-making phase. The ERP analysis epoch we selected was 900 ms, which included the waveform occurring 800 ms after the “heads or tails” stimulus was presented, as well as the 100 ms baseline period before the stimulus presentation. Based on the ERP total average map (Fig. 7) and topographic maps (Fig. 8) induced under the maximum and minimum conflict conditions obtained in the experiment, the time window of 400–450 ms after the stimulus presentation was selected. Using the SPSS statistical software, the average amplitudes at the F5 and F7 electrodes for the monetary temptations closest to and farthest from the honesty threshold were superimposed and averaged, followed by a paired-sample t-test. The results showed a significant difference between the maximum conflict group and the minimum conflict group, t (28) = 2.228, p = .034, Cohen’s d = 0.415. The maximum conflict group induced a greater LPC component than the minimum conflict group (M maximum conflict = 355.451 ± 368.946 µV, M minimum conflict = 262.587 ± 425.688 µV).

Discussion

Combining computational modeling and ERP data, this study attempted to answer the following two main questions: (1) Does individual honesty vary according to situation or is it consistent (invariable, dichotomous)? (2) What are the cognitive processes underlying honesty? That is, what is the dynamic time course of brain activity during the process of making the decision to be honest or deceptive?

Regarding the first question, honesty did not appear to be a stable trait across situations; instead, individuals had their own “honesty threshold”. Individuals can show honest behavior stably in various situations within the upper limit of their honesty threshold. However, in situations beyond the upper limit of their honesty threshold, they may no longer show honest behavior but show dishonest behavior. This study adopts “coin-flips” similar to16, and the experimental results prove that whether an individual is honest or not is not static. The results of behavioral data reveal the changing trend of individual honesty with the level of money temptation. Through computational modeling, it is determined that each individual has its own honesty threshold; that is, honesty is not a dichotomous variable, and a person is not black or white.

Regarding the second question, ERP technology was used to systematically explore the cognitive processes underlying honesty in individuals with higher honesty thresholds and lower honesty thresholds when resisting different monetary temptations. In addition to exploring the EEG activity of participants facing a conflict between the monetary temptation and maintenance of their own moral standards, the findings indicated that when the same individual resists different monetary temptations, the greater the monetary temptation is, the greater the P300 amplitude induced; likewise, the smaller the monetary temptation is, the smaller the P300 amplitude induced. When different individuals experience the same monetary temptation, the response of individuals with higher honesty thresholds is significantly different from that of individuals with lower honesty thresholds. Individuals with a higher honesty threshold exhibit less temptation, while individuals with a lower honesty threshold exhibit greater temptation. When the monetary temptation approaches the honesty threshold, an individual experiences greater cognitive conflict (greater LPC amplitudes).

Based on computational modeling, we proposed a behavioral model of the honesty threshold, in which honesty is not a stable trait. The computational modeling proposed was further rigorously verified by EEG analysis. Therefore, the present study presents model verification and empirical EEG data that provide better insights into the stability of honesty and the cognitive processes underlying honesty. This paper analyzed the essence of honesty from a thought-provoking perspective and examined the cognitive mechanism underlying the honest decision-making process from a broader perspective.

Honesty is not a stable trait

Honesty is a complex social characteristic of humans; to date, academic research on honesty has regarded it as a stable trait that can be displayed in various situations. This study found that honesty is not a stable trait across situations. By comparing the degree of dishonesty of individuals among five different monetary temptation levels, we found significant differences, which shows that when there is a chance to cheat, individuals exhibit dynamic changes in honesty. Moreover, the greater the monetary reward is, the greater the probability of individual dishonesty. This result shows that participants with greater deception are more sensitive to monetary rewards. Compared with more honest individuals, more deceptive individuals are more strongly driven by money when deciding whether to cheat, which is consistent with previous research results; that is, higher rewards will increase the possibility of dishonesty, and people will choose to cheat to obtain more financial rewards27,40. The results of this study show that individuals are more likely to cheat when the monetary reward is high, which is consistent with previous research that highlights the role of monetary rewards in influencing dishonest behavior27. Specifically, money sensitivity may influence the choice of honesty by triggering an internal drive for reward, affecting individuals’ decisions to behave honestly. Therefore, money sensitivity is not only a quantitative indicator of external temptation but also closely related to an individual’s internal motivation and self-control ability.

Specifically, the larger the monetary reward in this study was, the greater the P300 amplitude of individuals. When the monetary temptation was 3 yuan, the P300 amplitude in individuals was the largest, and when the monetary temptation was 0.01 yuan, the P300 amplitude in individuals was the smallest. The P300 component usually reflects the classification and evaluation of stimuli by individuals in the late attention period. The amplitude of P300 will be larger because individuals invest more attention resources in stimuli, and P300 reflects the individual’s rapid evaluation of reward stimuli alone. Researchers generally believe that the P300 component is sensitive to feedback values17. The larger the amount of monetary reward, the greater the amplitude of the P300. Therefore, more deceptive individuals are more sensitive when facing higher financial temptation, especially when making deceptive decisions, and they are driven by possible financial rewards to choose deception to a greater extent.

Why do individuals show honest or dishonest behavior?

Our results showed that in response to different levels of monetary temptation, individuals exhibit significant differences in the degree of honesty; that is, the honesty of individuals is not static. Furthermore, this study obtained honesty thresholds through computational modeling of behavioral data. This study adopted the “coin toss paradigm” to provide individuals with the possibility of cheating. Why were there significant differences in the degree of dishonesty among individuals among monetary temptation levels? Why did individuals choose to be honest in a tempting environment? What determines whether an individual is honest?

First, the purpose of dishonesty is often to gain resources, but this behavior is contrary to honesty. From this, it can be seen that deception involves a dilemma: to gain and to abide by one’s own moral standards25. When there is an opportunity to cheat, money temptation plays a vital role. Behavioral research shows that more greedy people are more likely to cheat against their own moral standards when faced with the temptation of money33. Deception reacts longer than honesty41. Event-related potentials found that the N2 component of the deception response was more negative than that of the honesty response20. Overall, these findings emphasize that higher rewards increase the likelihood of dishonesty and that people choose to cheat to obtain more monetary rewards27,40.

However, increasing evidence from psychology, economics and neuroscience shows that people not only care about maximizing their financial benefits but also have a strong belief in maintaining their self-concept11. Individuals tend to behave honestly to maintain their good self-concept14. Individuals can initiate specific self-concepts in different stimulus situations and make their behaviors consistent with the initiated self-concepts4. For example, some prosocial behavior studies have found that people internalize social rules and take them as the internal benchmark of their own behavior34. In an environment where there is an opportunity to cheat, people are in a dilemma between obtaining ideal monetary benefits and maintaining a positive self-image. Whether an individual decides to cheat usually involves a trade-off between the expected benefits and costs of honest/dishonest behavior. At this time, the way an individual views himself, or the moral nature of an individual, may prevent people from cheating. Violating one’s own moral standards requires a negative renewal of one’s self-concept, which is revulsive5. Therefore, even at the expense of potential monetary gains, people should maintain their self-concept26 and choose honesty.

Individuals usually decide whether to cheat by weighing the expected benefits and costs of honest or dishonest behavior3,46. The research results of38 suggested that honesty is not static: honest individuals can exhibit deception through decreased cognitive control, and deceptive individuals can show honesty through increased cognitive control. This is because whether an individual is honest depends on the moral essence of the individual. How should we interpret the conclusion by Speer et al.? How can we understand moral essence, as proposed by this study? Can a person’s moral essence simply be divided into honest or dishonest? Furthermore, what are the reasons why individuals are honest? This study proposes a new theoretical hypothesis: when individuals face honest decision-making, they form an “honesty threshold” based on the conflict between external temptation and internal moral standards. Specifically, when external temptation exceeds an individual’s honesty threshold, they may choose dishonest behavior; whereas when the external temptation is below the threshold, individuals are more likely to choose honesty. This hypothesis not only helps understand the dynamic changes in honest behavior but also provides a new perspective on how individuals weigh the conflict between morality and self-interest when facing temptations.

This study proves that honesty has a threshold through the computational modeling of behavioral data; that is, honesty should be understood as a continuous variable, and the moral essence of an individual cannot be simply divided into honesty or deception. Whether an individual is honest depends on the moral essence of the individual, and the so-called moral essence is the honesty threshold proposed in this study. It can be understood that all individuals are distributed in a continuum. At one extreme of this continuum, people are born with a tendency to be honest, while at the other extreme, people are born with a tendency to cheat. Specifically, the closer an individual’s honesty threshold is to the external temptation of money, the more conflicting an individual’s heart will be. When the threshold of honesty is greater than the temptation of money, the individual will show honesty with high probability; in contrast, when the threshold of honesty is less than the temptation of money, the individual will show deception with a high probability. That is, to maintain the participative inner balance of the individual in this continuum (that is, to choose money interests or maintain honesty), the individual often needs to struggle with his inner tendency to change his position in the continuum (the degree of honesty of the individual has changed). For example, a deceitful individual sometimes needs to do something honest to maintain his image. In contrast, an honest individual sometimes needs to profit from deception. Therefore, some honest people may also be classified as deceivers, and some deceivers may also be classified as honest people. Therefore, we observe that individuals with different honesty thresholds will make different honest reactions when facing the same money temptation, and the same individual is sometimes honest and sometimes lying when facing different money temptations. Whether a person is honest or not is not static, and everyone has his or her own honesty threshold. Whether an individual is honest or not mainly depends on the relative relationship between the honesty threshold of the individual and the external temptation of money.

The cognitive processes of honesty

Given the relationship between the individual honesty threshold and monetary temptation, we can understand why individuals show honest and dishonest behavior. Furthermore, through ERP technology, we can understand the cognitive processes underlying honesty in a more objective manner. Previous research paradigms mainly used passive deception paradigms (such as prompted responses and other experimental paradigms) to explore the cognitive processes underlying dishonest behavior. The paradigm related to passive deception can help researchers explore the role of cognitive control in dishonest behavior. However, these research paradigms mainly reflect the cognitive control process when individuals inhibit their real reactions, fabricate lies and make decisions about dishonest behaviors and lack the characteristics of spontaneity, risk and social interaction that dishonest behaviors should have in real situations, so their ecological validity is questionable35. Dishonesty in a real environment also includes a decision-making stage and a result feedback stage12.

Psychology has performed much research on the execution process of dishonest behavior (that is, the process of selecting and executing dishonest behavior), among which behavioral research13,42 and neural mechanisms8 all believe that the occurrence of dishonest behavior requires many cognitive resources and requires multiple executive functions to work together. In the previous discussion, we found that the stage of money temptation and the P300 component reflect the rapid processing of individual financial reward stimulation. What is the individual’s cognitive activity in the decision-making stage? Consistent with our assumptions, when the participants were confronted with the conflict between the temptation of money gain and the maintenance of their own moral principles, the LPC components induced by the left frontal lobe in the decision-making stage were significantly higher at the maximum conflict than at the minimum conflict, while the left superior frontal gyrus was always considered related to the higher cognitive functions of the brain (especially working memory)22. Previous studies have found that passive lying causes BOLD signal activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, especially in the left superior frontal gyrus, compared with honesty8,39, showing that dishonest behavior requires the participation of executive functions. Usually, LPC components represent intentional extraction in working memory, and larger LPC components mean more successful memory extraction32. LPC components mainly appear in the prefrontal cortex and temporal top. Previous studies have found that LPC components are related to conflict resolution23, inhibiting the processing of irrelevant information, and attention resources are concentrated on task-related information to resolve conflicts30; thus, the more difficult it is for individuals to inhibit irrelevant information, the smaller LPC components will be. The LPC component shows the left hemisphere effect in the electrode position distribution, and the left prefrontal cortex reflects the conflict monitoring and regulation process in the late stage of decision-making. Combined with previous research results, the LPC component located in the left prefrontal cortex may reflect the conflict resolution process in honest decision-making.

Most of the time, we are used to dividing people into good and bad people. Good people do good things and bad people do bad things. If a person is a good person, we expect that the individual will be consistent in words and deeds on all occasions; that is, we assume that human nature is unchanged. In fact, individuals are influenced by the situation, and their moral behavior is very changeable. In this study, we found that the moral character of honesty is not static, and with the increase in possible money gains, individual dishonest behavior will also increase. The moral quality of honesty cannot be simply divided into honesty and deception. Honesty is a continuous variable, and everyone has his or her own honesty threshold. This study puts forward the concept of the “honesty threshold” for the first time and explains why individuals sometimes behave honestly and sometimes behave deceitfully. Furthermore, this study, combined with event-related potential technology, reveals the cognitive process of honesty. Separated from the time of the individual in the opportunity to cheat, the occurrence of “resistance to the temptation of money” and the “decision-making stage” of two different cognitive processing processes, a more comprehensive study of honest decision-making cognitive processing mechanisms is needed.

Conclusion

This study employs computational modeling and event-related potential (ERP) technology to conduct a systematic and in-depth series of investigations into the moral quality of honesty. The main conclusions are as follows: Honesty is not fixed and cannot be simply categorized as either honest or dishonest for an individual. Honesty is not a stable trait that consistently manifests in all situations; rather, everyone develops their own “honesty threshold.” In situations within an individual’s honesty threshold, they can consistently exhibit honest behavior. However, when the situation exceeds this threshold, they may no longer exhibit honest behavior, but instead engage in dishonest behavior. The cognitive process of honesty involves at least two different cognitive processing stages: the “resisting money temptation” stage and the “decision-making stage.” In situations where there is an opportunity to cheat, the P300 component reflects the individual’s classification and evaluation of money-related stimuli during the process of resisting monetary temptation, while the LPC component reflects the inner psychological conflict between choosing honesty and opting for monetary gain during the “decision-making stage.” In other words, the cognitive processing of honesty involves at least two distinct sub-processes.

The findings of this study have important implications not only for individual moral decision-making but also for the overall moral level and social trust of society. By understanding and applying the concept of the “honesty threshold,” we can promote honest behavior on a larger scale. This concept provides us with a framework to understand how individuals make moral decisions when facing external temptations, thereby fostering the development of a culture of honesty in society. As more people in society are able to maintain honesty in the face of temptation, it not only reduces social issues such as corruption and dishonesty but also strengthens social trust and promotes healthy economic development. A society built on trust and honesty can enhance cooperation, reduce fraud and unfair competition, and is crucial for creating a fairer and more sustainable social environment.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of South China Normal University (SCNU) (Ethics Approval Number: SCNU-PSY-2020-4-069). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

A total of 33 college students (12 females) participated in the experiment. The participants had an average age of 20.03 ± 1.087 years, normal vision or corrected vision, were right-handed, and no history of mental illness. Before the experiment, all the participants signed a written informed consent form. After the experiment, they were given certain experimental rewards according to their decision-making results and told to keep the experimental process and results confidential from the outside world.

To ensure sufficient statistical power, we conducted a priori power analyses for both behavioral and EEG data analyses using G*Power (version 3.1). For the behavioral analysis, which used a single-factor repeated measures design, the analysis assumed a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.25), a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80. The result indicated a minimum sample size of 25 participants. For the EEG analysis, which used a 2 × 3 mixed design, the analysis assumed a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.25), a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80. The result indicated a minimum sample size of 34 participants. Based on these calculations, we recruited 33 participants to balance the statistical requirements of both analyses.

Experimental design

Behavioral data were designed by a single-factor intraparticipant experiment. The independent variable is money temptation (3 yuan, 2 yuan, 1 yuan, 0.1 yuan, 0.01 yuan), and the dependent variable is the number of “coin toss” tasks that individuals think they are right.

In the stage of resisting money temptation, 2 (groups: low threshold group and high threshold group) × 3 (temptation level: 3 yuan, 2 yuan and 0.01 yuan) were used for repeated measurement variance analysis. The two factors were an intergroup factor: group (low threshold group, high threshold group) and an intragroup factor: temptation level (3 yuan, 2 yuan, 0.01 yuan). The dependent variable is the EEG activity evoked by the participants resisting the temptation of money. Two participants did not complete the experiment because of personal reasons, and the EEG data of three others were eliminated because of artifact rejection. Therefore, there were 28 effective participants (12 females), with an average age of 19.96 ± 1.105 years. Although the final EEG sample size was slightly lower than the calculated minimum of 34 participants, the results are still considered reliable due to the use of robust statistical methods.

In the stage of resisting money temptation, according to the size of the honesty threshold in Table 1, all participants were divided into a high honesty threshold group and a low honesty threshold group, and the EEG activities of the high honesty threshold group and low honesty threshold group were investigated when resisting different money temptations. The first is to determine the EEG components when the participants resist the temptation of money. The low threshold group was the most tempted by money when facing 3 yuan; when the high threshold group faced 0.01 yuan, it was the least tempted by money. Therefore, we assume that the difference between the group with the greatest temptation of money and the group with the least temptation of money is the most significant and thus determine that the EEG component is the EEG component when the participants resist the temptation of money. Then, the EEG components were verified in two steps. Assuming that the same participants face different money temptations, the greater the money temptation is, the greater the EEG components evoked by the participants when resisting money temptation. In contrast, the smaller the temptation of money is, the smaller the EEG components induced by the participants when resisting the temptation of money. It is assumed that when the two groups of participants with high and low thresholds face the same money temptation, the participants with high thresholds have less EEG activity when resisting money temptation.

In the decision-making stage, a single-factor intraparticipant experimental design was used. The independent variable is money temptation (3 yuan, 2 yuan, 1 yuan, 0.1 yuan, 0.01 yuan), and the dependent variable is EEG activity evoked by the inner conflict between the individual facing money temptation and maintaining his own moral standards. There were 29 effective participants (12 females) with an average age of 20.03 ± 1.149 years. In the decision-making stage, the EEG activity of the participants in the conflict between the temptation of money gain and the maintenance of their own moral standards was explored, and the different EEG activity between the most conflicted group and the most conflicted group was investigated.

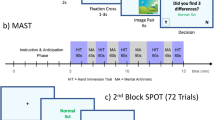

Procedures

The experiment uses the paradigm of coin-flips. As shown in Fig. 9, at the beginning of the experiment, a 1000-millisecond watching screen “+” is presented first, and then a “please predict” screen with a certain amount of money appears randomly. When this screen appears, the task of the participants is to predict whether the coins thrown in this round are heads or tails inside their mind. After the prediction, press the “space bar”. Then, there is the actual coin toss result, that is, heads or tails (presenting 1000 ms). Then, it presents “Is your prediction correct?“. On this screen, the task of the participants is to judge whether they guessed the result of this round of coin toss (press the “F” key correctly and press the “J” key incorrectly). After the keys were pressed, an all-black blank screen was presented, and the blank screen was randomly presented for 1000 ~ 2000 ms to prevent the participants from accurately predicting the time point of the event. Finally, a 1500 ms feedback screen was presented: “Get … yuan” or “Deduct … yuan”. After the feedback screen was presented, an all-black blank screen was presented, and the blank screen was randomly presented for 1000 ~ 2000 ms. the participants were informed that the task in the experiment was to predict whether the coins thrown randomly are positive or negative. The purpose of the experiment is to see if the stimulation of different economic interests will affect the prediction ability of individuals. Therefore, before each coin is thrown, the amount of money (0.01 yuan, 0.1 yuan, 1 yuan, 2 yuan, 3 yuan) will be given. If the participant predicts correctly, the participant will receive the money, and if the participant predicts incorrectly, the computer will subtract the money. The computer automatically accumulates the amount predicted each time. If the accumulated amount is positive, the participants will receive this money in addition to the basic participant fee. If the accumulated amount of the participant is negative, the basic participant fee of the participant will not be deducted.

There are five conditions for money temptation: 0.01 yuan, 0.1 yuan, 1 yuan, 2 yuan and 3 yuan. These five money conditions are all 48 trials, and the positive and negative sides of each kind of money condition are 24 trials, totaling 240 trials. During the experiment, the different money conditions appear randomly. There were 12 exercises before the formal experiment. After ensuring that the participants were familiar with the experimental process, the formal experiment was started, and the exercises were not included in the follow-up statistical analysis. The participants were given a rest every 72 times. The duration of rest was determined by the participants themselves.

All the participants voluntarily participated in this experiment. The participants were invited to a quiet standard laboratory. The main test staff told the participants the operating methods and notices in the experiment, and the participants signed the informed consent form to start the experiment. The participants sat alone in a suitable laboratory, with their eyes 80 cm away from the computer screen, minimizing the number of blinks and keeping their eyes fixed in the center of the screen after completing an experimental trial. The participants were told to sit comfortably in a chair with an EEG acquisition cap of appropriate size on their head. The angle between the line of sight and the target stimulus was maintained at 8.08° × 9.65°. All stimuli are presented on a black background, and the stimuli are in the center of the computer screen. All experiments were generated and controlled by E-Prime software (version 2.0). Before the formal start of the experiment, the participants were told that after the experiment was completed, in addition to the basic fees, they would also receive monetary rewards in the task according to their decision-making results, and then the participants left the laboratory after receiving the fees.

EEG acquisition and preprocessing

The experimental equipment used was the Neuroscan64 EEG recording and analysis system. It employed a 64-channel elastic cap, which was extended according to the international 10–20 system, to record the participants’ EEG activity. The reference electrode was placed at the REF point, and the ground electrode was placed at the GROUND point. The right horizontal electrooculogram (HEOG) and the left inferior orbital vertical electrooculogram (VEOG) were also recorded. The bandpass filter was set to 0.016 to 100 Hz, the sampling rate was 1000 Hz, and a 50 Hz notch filter (to remove electrical interference from the power supply) was applied. The signal was amplified by 100,000 times. The impedance between the scalp and the electrodes was kept below 5 kΩ. The EEG data were offline processed with an analysis window of 900 ms (from − 100 ms to 800 ms), with the reference electrodes at the left and right mastoids. The vertical eye movement artifacts were removed using the semi-automatic mode of Covar in Curry 8.0.6. During preprocessing, five channels (FP1, FPZ, FP2, AF3, and AF4) were excluded due to impedances exceeding 10 kΩ. Epochs with excessive eye movements or other movement artifacts were identified by visual inspection and manually removed. Ocular artifact reduction was performed using the semi-automatic mode of Covar in Curry 8.0.6s.

In the monetary temptation phase, the EEG data were segmented according to the five monetary amounts (0.01 yuan, 0.1 yuan, 1 yuan, 2 yuan, and 3 yuan). During the decision-making process, the EEG data were segmented according to the “heads” and “tails” (e.g., the previous screen displayed 2 yuan with heads and tails). After continuous EEG recordings were completed, offline data processing was performed using Curry 8.0.6 S software to analyze the recorded EEG data.

The ERP waveform was time-locked to the onset of the stimulus presented on the monetary temptation screen. Based on the shortest average response time for decision-making, the average analysis window (epoch) for the ERP data was set to 900 ms, including the waveform occurring 800 ms after the monetary stimulus presentation and the baseline period occurring 100 ms before the stimulus. Data were overlaid and averaged according to event type and segment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allingham, M. G. & Sandmo, A. Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. J. Public. Econ. 1 (3–4), 323–338 (1972).

Baumeister, R. F. Esteem threat, Self-Regulatory Breakdown, and emotional distress as factors in self-defeating behavior. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1 (2), 145–174 (1997).

Becker, G. S. Crime and punishment: an Economic Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 76 (2), 169–217 (1968).

Bersoff, D. M. Why good people sometimes do bad things: motivated reasoning and unethical behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 25 (1), 28–39 (1999).

Berthoz, S., Grèzes, J., Armony, J. L., Passingham, R. E. & Dolan, R. J. Affective response to one’s own moral violations. NeuroImage 31 (2), 945–950 (2006).

Burgoon, J. K. & Buller, D. B. Interpersonal deception Theory.: reflections on the Nature of Theory Building and the theoretical status of interpersonal deception theory. Communication Theory. 6 (3), 311–328 (1996).

Chiou, W. B., Wu, W. H. & Cheng, W. Self-control and honesty depend on exposure to pictures of the opposite sex in men but not women. Evol. Hum. Behav. 38 (5), 616–625 (2017).

Christ, S. E., Van Essen, D. C., Watson, J. M., Brubaker, L. E. & McDermott, K. B. The contributions of prefrontal cortex and executive control to deception: evidence from activation likelihood estimate meta-analyses. Cereb. Cortex. 19 (7), 1557–1566 (2009).

Chuderski, A., Senderecka, M., Kałamała, P., Kroczek, B. & Ociepka, M. ERP correlates of the conflict level in the multi-response Stroop task. Brain Res. 1650, 93–102 (2016).

Cohn, A., Fehr, E. & Maréchal, M. A. Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature 516 (7529), 86–89 (2014).

Dhar, R. & Wertenbroch, K. Self-signaling and the costs and benefits of Temptation in Consumer Choice. J. Mark. Res. 49 (1), 15–25 (2012).

Ding, X. P., Sai, L., Fu, G., Liu, J. & Lee, K. Neural correlates of second-order verbal deception: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) study. NeuroImage 87, 505–514 (2014).

Evans, A. D. & Lee, K. Verbal deception from late childhood to middle adolescence and its relation to executive functioning skills. Dev. Psychol. 47 (4), 1108–1116 (2011).

Forehand, M. R. & Deshpandé, R. What we see makes us who we are: priming ethnic self-awareness and advertising response. J. Mark. Res. 38 (3), 336–348 (2001).

Gächter, S. & Schulz, J. F. Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies. Nature 531 (7595), 496–499 (2016).

Greene, J. D. & Paxton, J. M. Patterns of neural activity associated with honest and dishonest moral decisions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (30), 12506–12511 (2009).

Hajcak, G., Holroyd, C. B., Moser, J. S. & Simons, R. F. Brain potentials associated with expected and unexpected good and bad outcomes. Psychophysiology 42 (2), 161–170 (2005).

Hajcak, G., Moser, J. S., Holroyd, C. B. & Simons, R. F. The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biol. Psychol. 71 (2), 148–154 (2006).

Harris, S., Mussen, P. & Rutherford, E. Some cognitive, behavioral and personality correlates of maturity of moral judgment. J. Genet. Psychol. 128 (1st Half), 123–135 (1976).

Hu, X., Pornpattananangkul, N. & Nusslock, R. Executive control- and reward-related neural processes associated with the opportunity to engage in voluntary dishonest moral decision making. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 15 (2), 475–491 (2015).

Hyun, M. et al. Self-serving bias in performance goal achievement appraisals: evidence from long-distance runners. Front. Psychol. 13, 762436 (2022).

Johnson, M. K., Raye, C. L., Mitchell, K. J., Greene, E. J. & Anderson, A. W. FMRI evidence for an organization of prefrontal cortex by both type of process and type of information. Cereb. Cortex. 13 (3), 265–273 (2003).

Larson, M. J., Kaufman, D. A. S. & Perlstein, W. M. Neural time course of conflict adaptation effects on the Stroop task. Neuropsychologia 47 (3), 663–670 (2009).

Lombard, E. & Gibson Brandon, R. N. Do wealth managers understand codes of conduct and their ethical dilemmas? Lessons from an online survey. J. Bus. Ethics. 189, 553–572 (2023).

Mazar, N., Amir, O. & Ariely, D. The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of Self-Concept maintenance. J. Mark. Res. 45 (6), 633–644 (2008a).

Mazar, N., Amir, O. & Ariely, D. The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of Self-Concept maintenance. J. Mark. Res. 45 (6), 633–644 (2008b).

Mazar, N. & Ariely, D. Dishonesty in Everyday Life and its policy implications. J. Public. Policy Mark. 25 (1), 117–126 (2006).

Meinhardt, J., Sodian, B., Thoermer, C., Döhnel, K. & Sommer, M. True- and false-belief reasoning in children and adults: an event-related potential study of theory of mind. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 1 (1), 67–76 (2011).

Mohamed, F. B. et al. Brain mapping of deception and truth telling about an ecologically valid situation: functional MR imaging and polygraph investigation–initial experience. Radiology 238 (2), 679–688 (2006).

Polich, J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin. Neurophysiology: Official J. Int. Federation Clin. Neurophysiol. 118 (10), 2128–2148 (2007).

Rosenfeld, J. P., Ellwanger, J. & Sweet, J. Detecting simulated amnesia with event-related brain potentials. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 19 (1), 1–11 (1995).

Rugg, M. D. & Allan, K. Memory retrieval: an electrophysiological perspective. In: Gazzaniga MS (ed) The new cognitive neuro- sciences, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge, 805–816 (2000).

Seuntjens, T. G., Zeelenberg, M., van de Ven, N. & Breugelmans, S. M. Greedy bastards: testing the relationship between wanting more and unethical behavior. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 138, 147–156 (2019).

Shaw, D. M. & Campbell, E. Q. Internalization of a Moral Norm and External supports. Sociol. Q. 3 (1), 57–71 (1962).

Sip, K. E., Roepstorff, A., McGregor, W. & Frith, C. D. Detecting deception: the scope and limits. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12 (2), 48–53 (2008).

Sooter, N. M., Brandon, R. G. & Ugazio, G. Honesty is predicted by moral values and economic incentives but is unaffected by acute stress. J. Behav. Experimental Finance. 41, 100899 (2024).

Speer, S. P. H., Martinovici, A., Smidts, A. & Boksem, M. A. S. The acute effects of stress on dishonesty are moderated by individual differences in moral default. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 3984 (2023).

Speer, S. P. H., Smidts, A. & Boksem, M. A. S. Cognitive control increases honesty in cheaters but cheating in those who are honest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(32), 19080–19091. (2020).

Spence, S. A. et al. Behavioural and functional anatomical correlates of deception in humans. Neuroreport 12 (13), 2849–2853 (2001).

Straughan, R. D. & Lynn, M. The effects of Salesperson compensation on perceptions of salesperson honesty. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32 (4), 719–731 (2002).

Suchotzki, K., Verschuere, B., Van Bockstaele, B., Ben-Shakhar, G. & Crombez, G. Lying takes time: a meta-analysis on reaction time measures of deception. Psychol. Bull. 143 (4), 428–453 (2017).

Talwar, V. & Lee, K. Social and Cognitive correlates of Childrens lying Behavior. Child Dev. 79 (4), 866–881 (2008).

Walczyk, J. J., Roper, K. S., Seemann, E. & Humphrey, A. M. Cognitive mechanisms underlying lying to questions: response time as a cue to deception. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 17 (7), 755–774 (2003).

Weisel, O. & Shalvi, S. The collaborative roots of corruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(34), 10651–10656. (2015).

West, R. & Alain, C. Evidence for the transient nature of a neural system supporting goal-directed action. Cereb. Cortex. 10 (8), 748–752 (2000).

Yitzhaki, S. Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. J. Public. Econ. 3 (2), 201–202 (1974).

Zhang, T., Sha, W., Zheng, X., Ouyang, H. & Li, H. Inhibiting one’s own knowledge in false belief reasoning: an ERP study. Neurosci. Lett. 467 (3), 194–198 (2009).

Zhao, L., Li, Y., Sun, W., Zheng, Y. & Harris, P. L. Hearing about a story character’s negative emotional reaction to having been dishonest causes young children to cheat less. Dev. Sci., 26(2), e13313. (2023).

Zuckerman, M., DePaulo, B. M. & Rosenthal, R. Verbal and Nonverbal Communication of Deception. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 14, 1–59 (1981).

Acknowledgements

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to express our gratitude for the invaluable insights provided by Lianggen Guo and the support extended by the Guangdong Justice Police Vocational College. We are deeply appreciative of the financial support provided by the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (19ZDA360), the Project of Key Institute of Humanities and Social Science, Ministry of Education of China (16JJD880025), the Social Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (GD24YXL03), and the Basic and Applied Research Foundation of Guangzhou, China (SL2023A04J00644).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: P.J., C.M., and L.M. designed research; P.J., R.G., H.G., L.Z., J.W., and W.Z. performed research; P.J., and C.M. analyzed data; and P.J., C.M., and L.M. wrote the paper. P.J. is the first author of the study and made primary contributions to the research design, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, P., Gao, R., Zhong, W. et al. Honesty threshold affects individuals’ resistance to monetary temptations. Sci Rep 15, 1835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85926-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85926-y