Abstract

Despite maintaining a lower mortality rate and greater control of victims infected by COVID-19, the world’s population and science are still confronted with this coronavirus. Therefore, the aim was to assess the association between sociodemographic factors and the level of knowledge and attitudes of dental students regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. This cross-sectional study evaluated 503 dental students from the capital city and one Peruvian province between February and June 2022. A validated 13-item questionnaire was used. A Poisson regression model with robust variance was used to evaluate the influence of the variables sex, age, year of study, marital status, place of origin, death of a family member due to COVID-19, and history of COVID-19, with the level of knowledge and attitudes of the dental students, considering a significance level of p < 0.05. Of the total participants, 14.3% showed sufficient knowledge, and 89.3% showed positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, those from the capital city were 52% less likely to have sufficient knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19, compared to those from the province (APR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.31–0.75). Moreover, none of the variables considered in this study were significantly associated with attitudes toward this topic (p > 0.05). A minority of dental students presented sufficient knowledge, while the majority presented positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. In addition, being from the capital city was a limiting factor for sufficient knowledge. The variables sex, age, year of study, marital status, place of origin, death of a family member due to COVID-19, and history of COVID-19 were not influential factors for positive attitudes on this topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to changes in the occupational, social, economic, educational, and health fields1. The global case fatality rate for this infectious disease stood at 1.13% as of July 20222. According to the report from 5 March 2023, there were a total of 676,609,955 confirmed cases and 6,881,955 deaths worldwide3. Furthermore, the World Health Organization has issued a warning that COVID-19 infections have increased by 52% in just one month, and this trend is expected to continue until 20244. As a result, it is now a concern for health systems in all countries around the world5, despite advances in vaccination, diagnosis, and treatment methods6.

At the time of conducting this research, Peru was in the third wave of COVID-19 infection reaching historical peaks of infected people, for example, on 23 January 2022, 340,025 confirmed cases were reported causing 859 deaths, reaching a total of 1,479 deaths due to this disease on 6 February 20223. Reports at the time indicated that omicron was the predominant variant across the country7. In parallel, the Ministry of Health (MINSA) reported that 67% of the general population had not yet received the third booster dose of the Covid-19 vaccine8.

Certain risks inherent to medical practice expose healthcare professionals. However, dentists have a higher risk of exposure to coronavirus due to their direct contact with saliva because, in clinical practice, they work in close contact with the oral cavities of patients, which further increases the risk by generating aerosols with rotating instruments or low- or high-speed turbines used in dental procedures1,9,10,11. It is because dental professionals and students are likely to be exposed to known or suspected sources of the SARS-CoV-2 virus during procedures that create bioaerosols1,12. This is why the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has put them in the “very high exposure risk” category. In addition, this pathogen can survive on solid surfaces exposed to body fluids from a few hours to several days5,13,14. It is evident that one of the effective strategies to halt or curtail the propagation of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens in the dental environment is to undertake a meticulous disinfection of hands, surfaces, medical equipment, and air15. This approach has been shown to play a pivotal role in mitigating the risk of cross-transmission of disease, thereby facilitating a more expeditious and secure recovery for patients, in addition to safeguarding the well-being of oral healthcare professionals. Furthermore, this approach has been shown to reduce the financial burden associated with medical complications, thereby enhancing the efficiency and quality of dental services15,16.

On the other hand, it is undeniable that COVID-19 affected the teaching-learning process and dental research, which forced dental schools to modify their traditional way of teaching to a remote teaching mode to adapt to the pandemic17. At the time of this study, universities in Peru were transitioning back to face-to-face teaching18. This posed a challenge for these institutions, particularly in adapting to clinical training, as it would be difficult to resume patient care while ensuring maximum protection against infection1,17. Therefore, stricter biosecurity standards, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and disinfection protocols were established to control and reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection9. This will help students identify the necessary measures and barriers to prevent further infections and the spread of the virus. It is important to understand the technical-scientific reasons behind these measures in order to increase awareness of the importance of prevention. This will not only save lives but also prevent cross-infection, especially for vulnerable people9,19. In view of the above, the aim was to assess the association between sociodemographic factors and the level of knowledge and attitudes of dental students regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. The null hypothesis considered was that there are no sociodemographic factors associated with the knowledge and attitudes of dental students on this topic.

Methods

Study design

An analytical, cross-sectional, prospective, observational study was conducted. This report was written in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies20 and was conducted from February to June 2022 at the School of Stomatology of the Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista (UPSJB), based in Lima (Peruvian capital) and a branch in Ica (Peruvian province).

Study population

The total population consisted of 643 students from the 1st to the 5th year of the professional career of Stomatology. The minimum sample size with EPIDAT 4.2 was 241 with the formula for estimating a proportion with finite population, considering a 95% confidence level, 5% estimation error and p = 50%. Therefore, in order to ensure the largest number of participants and to ensure statistical inference, it was decided to invite the entire population, provided that the total number of students was above the minimum required sample size, according to the eligibility criteria. Finally, the target population was N = 503 (93 1st year, 86 2nd year, 74 3rd year, 84 4th year, 123 5th year), with 299 participants from Lima (64 1st year, 42 2nd year, 37 3rd year, 56 4th year, 68 5th year) and 204 participants from Ica (29 1st year, 44 2nd year, 37 3rd year, 28 4th year, 55 5th year) [Fig. 1].

Variables

The independent variables considered in this study were: gender21, and age22; and as possible confounding variables the year of study23, marital status24, place of origin25, death of a family member due to COVID-1926, and history of COVID-1927. While the dependent variables were knowledge and attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Instrument

A validated 13-question questionnaire28 with two dimensions, one on knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 (K1-K10) (see supplementary material) and the other on attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 (A1-A3), was used. Two English-speaking dentists translated and adapted the questionnaire into Spanish. Subsequently, three judges (a Doctor in Public Health and two researchers in Stomatology) with more than 15 years of experience validated the cross-culturality and the content of the instrument. They evaluated the relevance, objectivity, relevance, timeliness, sufficiency, clarity and methodology of the questionnaire, obtaining an acceptable Aiken’s V (V = 0.89; 95% CI: 0.85–0.92).

The knowledge dimension included 10 questions, K1 to K8 were single choice and the last two questions K9 and K10 were multiple choice. Each correct answer was assigned 1 point and an incorrect answer was assigned 0 points. The overall knowledge level was defined according to the following range: insufficient knowledge (< 7 points) / sufficient knowledge (≥ 7 points). The attitude dimension consisted of 3 questions (A1 to A3) with Likert scale responses being strongly disagree with 1 point, disagree with 2 points, neutral with 3 points, agree with 4 points and strongly agree with 5 points. The overall attitude was considered negative or unsatisfactory (< 10 points) / Positive or satisfactory attitude (≥ 10 points). To establish the optimal cut-off point for both dimensions, a three-level scale (low, medium and high) was made with the total scores based on Stanones’ rule [mean (x̄) ± 0.75 (standard deviation)], setting the cut-off point for knowledge at 7 points and for attitudes at 10 points. Furthermore, the accuracy of these cut-off points was validated using Livingston’s K2 coefficient, which resulted in 0.931 for knowledge and 0.915 for attitudes, which are acceptable values.

The internal consistency of the instrument was tested by Cronbach’s alpha reliability analysis, obtaining an (α) = 0.781 (95% CI: 0.711–0.840) for the knowledge dimension, and an (α) = 0.801 (95% CI: 0.722–0.860) for the attitude dimension. In addition, the concordance of scores was assessed in 100 randomly selected participants at two different times within 10 days, altering the order of the questions to avoid recall bias29, with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) being very good for knowledge (ICC = 0.971; 95% CI: 0.957–0.981) and attitudes (ICC = 0.976; 95% CI: 0.964–0.984).

Procedure

The questionnaire was distributed via institutional e-mails and personal social networks of each participant, via a link created in the virtual platform Google Classroom®. If no response was received, the invitation was repeated up to 3 times, with a frequency of once a week. The students’ informed consent to participate in the survey was at the beginning of the questionnaire, followed by the instructions for completing the questionnaire. However, they were free not to complete the questionnaire if they considered it appropriate. The online questionnaire was set up so that it could only be completed once with a maximum time limit of 10 min. In addition, they were asked to enter the initials of their first name, surname and age (example: GPSR23) to filter out repetitions in case someone accessed the link from two different email addresses. On the other hand, no students received incentives to participate in the study and had access to the questionnaire from February to June 2022. Only the principal investigator had access to the information collected and, to ensure confidentiality, it was stored on a digital device with a password. Finally, the results of the study were sent to whoever requested them via mail upon completion of the research.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0. Descriptive statistics were applied to obtain absolute and relative frequency tables and bar charts. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for bivariate analysis and for expected values less than 5 Fisher’s exact test was used. For multivariate analysis, a Poisson regression model with robust variance was used. All analyses were performed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Ethical issues

The present study respected the bioethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki related to confidentiality, respect, freedom and non-maleficence30. Approval was obtained from an institutional ethics committee of the Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista whose resolution was No. 8-2022-CIEI-UPSJB dated January 17, 2022. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In addition, all participants gave their voluntary informed consent on the first page of the online questionnaire.

Results

The response rate was 78.23% and the average age of the 503 participants was 24.5 ± 7.2 years. The majority were female with 62.8% of the total respondents. The most frequent age group was ≥ 22 years with 55.7%. The relative frequency of students by academic year ranged from 17.5 to 22.7%. Singles were the most predominant group with 88.3% of the total. In addition, 59.4% of the total number of participants were from the capital. Finally, 40.6% had lost at least one family member to COVID-19 and 51.5% had a history of having been ill with COVID-19 [Table 1].

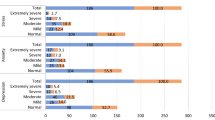

Of the 503 participants, 85.69% (95% CI: 82.38 − 88.99%) showed insufficient knowledge, while 14.31% (95% CI: 6.22 − 22.40%) showed sufficient knowledge; and finally, 10.74% (95% CI: 2.48 − 18.99%) showed negative attitudes, while 89.26% (95% CI: 86.40 − 92.13%) showed positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 [Fig. 2].

Regarding knowledge of disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in dental students, statistically significant age group associations were obtained with K1 (What is recommended to use to clean visibly soiled hands? ), K3 (How long can coronavirus remain infectious on inanimate surfaces? ) K7 (What is an effective hand disinfectant against coronavirus? ), K8 (What is the recommended disinfectant against coronavirus to disinfect waste before disposal? ) and K10 (What disinfectants and for how long should be applied to surfaces against coronavirus? ) (p = 0.028, p = 0.020, p < 0.001, p = 0.020 and p = 0.025; respectively). Gender was significantly associated with K5 (How long can SARS-COV-2 remain infective on stainless steel and plastic? ) and K8 (p = 0.049 and p = 0.009; respectively). Year of study was significantly associated with K1, K2 (What does the efficacy of a disinfectant against coronavirus depend on? ), K3 and K8 (p = 0.005, p = 0.047, p = 0.012 and p = 0.009; respectively). Marital status was significantly associated with K1, K6 (What should the disinfectants used against coronaviruses to disinfect floors, walls and dental arbitrary/operatory contain? ) and K7 (p = 0.015, p = 0.030 and p = 0.013; respectively); while place of origin was significantly associated with K7 (p < 0.001). In addition, having had at least one family member who died of COVID-19 was significantly associated with K1 and K10 (p = 0.019 and p = 0.028, respectively). Finally, having a history of COVID-19 was significantly associated with K1, K3 (p = 0.018 and p = 0.009; respectively) [Table 2].

Regarding attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in dental students, statistically significant associations of age group were obtained with A1 (There is a high risk in a dental practice of becoming infected with SAR-CoV-2.) (p = 0.044). In addition, place of origin was significantly associated with A1 and A3 (To prevent COVID-19, it is important to disinfect frequently touched surfaces in a dental clinic) (p = 0.016 and p = 0.003; respectively). Finally, having had at least one family member die from COVID-19 was significantly associated with A2 (Following the disinfection guidelines will help in reducing the risk of becoming infected by SARS-CoV-2) (p = 0.001) [Table 3].

On the other hand, it could be observed that knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19, was significantly associated with the place of origin of the students (p = 0.002), while attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 was significantly associated with having had at least one family member died from COVID-19 (p = 0.037) [Table 4].

According to the crude Poisson regression model analysis with robust variance, knowledge (sufficient = 1 / insufficient = 0) and attitude (positive = 1 / negative = 0) regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 were considered as dependent variables, and gender and age as independent variables, and year of study, marital status, place of origin, death of a family member due to COVID-19, and history of COVID-19 as possible confounding variables. When fitting the model with Poisson multiple regression with robust variance, it was observed that those in the capital city were 52% less likely to have sufficient knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19, compared to those in the province (APR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.31–0.75). In addition, it was observed that none of the variables considered in this study, i.e., sex, age group, year of study, marital status, origin, death of family member by covid-19, and history of covid-19, were influential factors in positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in dental students (p > 0.05) [Table 5].

Discussion

Infection control remains one of the most important challenges in health care delivery worldwide, including dental schools/colleges, as the adoption of infectious disease prevention and control measures in clinical settings are crucial to provide a safe environment for students, patients, educators, and health care professionals5,31. Surface disinfection is one of the aspects to which most attention should be paid, together with biosafety measures and the use of appropriate protective elements32. In this sense, it is important for students to have the necessary knowledge about disinfection protocols in order to guarantee adequate performance in the clinical area. Therefore, the aim of this research was to evaluate the association of sociodemographic factors with the level of knowledge and attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in dental students, so due to the results obtained, the null hypothesis had to be rejected.

The results of this study indicated that 85.7% of the students presented insufficient knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. These results differ from those reported by Pathak et al.33, who found that overall more than 60% of dental students in India considered temperature control and hand disinfection as necessary measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In addition, they found that liquid soap with water or an alcohol-based hand sanitiser > 60% could be the most effective form of hand hygiene, they also found that sodium hypochlorite was the most effective way of disinfecting surgical surfaces, and finally they considered the use of a mouthwash by the patient prior to treatment to be necessary. This discrepancy could be due to the fact that the present research was conducted in the year 2022, which probably led students to lower their guard or downplay the importance of disinfection protocols against COVID-1934, as they probably felt safe with the third dose of the coronavirus vaccine35, which may have led them to neglect acquiring and/or updating their knowledge on this topic. In contrast, the study by Pathak et al.33 was conducted in the year 2020, a time when students had not been vaccinated and therefore used to update their knowledge and adopt precautionary measures according to accredited daily news, webinars, online education programme and published scientific articles, among others33.

On the other hand, place of origin was found to be significantly associated with knowledge of the most effective hand sanitiser against coronavirus. This could perhaps be attributed to the fact that students from the provinces, having information about the exacerbated increase in cases of COVID-19 in the Peruvian capital36, sought further training on which disinfectants work as an effective alternative for hand cleaning to prevent the spread of the disease37. In this regard, WHO recommended rubbing hands with an alcohol concentration of 60–80% after hand washing for adequate disinfection38.

With regard to attitudes, it was observed that 89.3% of the students had positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. This indicates that students have good intentions to put it into practice, since as future health professionals they have an obligation and responsibility to decrease the risk of contagion derived from health care work, encouraging them to have positive attitudes39, even without having sufficient knowledge to implement disinfection guidelines against COVID-1928. This agrees with Umeizudike et al., who reported that half of the Nigerian dental students had sufficient knowledge of COVID-19, although 95.1% had positive attitudes towards infection control40.

While it is true that in this study, the bivariable analysis showed that attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 were significantly associated with having at least one sick family member. However, in a multivariable regression model, it was not considered to be an influential factor, showing that the association of variables does not always necessarily indicate causality or influence41,42. Therefore, this finding may indicate that having a sick family member was not a determining factor in having a good attitude towards this issue, as dental students may have felt that the responsibility and commitment to prevent infection was inherent in their profession with good clinical practice, regardless of the risk of exposing a vulnerable family member43,44.

On the other hand, a novel finding of the present study, under a multivariate statistical analysis model, was that students in the capital were 52% less likely to have sufficient knowledge regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 compared to those in the provinces. These results could be due to the fact that, at the time of the study, students from the provinces felt the need to be more informed and updated, due to the fear they felt when they heard on the news that there was a considerable increase in COVID-19 cases in the Peruvian capital36, and even more so knowing that if this had happened to them, the situation would have become very critical, as health centres in the Peruvian provinces still did not have sufficient medical staff and infrastructure to deal with the disease45. Furthermore, it was observed that none of the variables considered in this study, i.e., gender, age group, year of study, marital status, origin, death of a family member due to covid-19, and history of covid-19, were associated or influential factors in the positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in dental students. This could be attributed to the fact that more than 80% of all participants, according to the variables mentioned, presented positive attitudes, perhaps because the students were in similar conditions, as they were all in the process of adapting to face-to-face classes and already had protocols established by the university and the Ministry of Health for disinfection, biosecurity, and preventive measures for patient care11,46. It is also likely that the gaps between the categories of each variable were closed, with respect to positive attitudes, because the vast majority of students had received the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine1.

Unlike other health science students, dental students are at an increased risk of infection due to the nature of their clinical training. This is because they work in the oral cavity of patients and are frequently exposed to contaminated bioaerosols, saliva, blood, and other body fluids31,47. In order to provide patients with safe and effective dental treatment, infection control is of utmost importance. Research has shown that coronaviruses can persist on surfaces for varying lengths of time, ranging from a few hours to several days5,13,14, depending on factors such as the nature of the surface, humidity, and temperature14. To control the spread of the virus, it is essential for students to recognize the threat and maintain strict disinfection protocols. They should also use personal protective equipment and take necessary measures during their dental practice5,48,49.

Among the limitations of the present research, we can mention that it was not possible to survey students in person, because the education sector was in the process of adapting to face-to-face teaching, nor was it possible to monitor knowledge about pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic disinfection in order to assess the variation and durability of this knowledge over time. Another limitation of this research is that a thoroughly validated instrument was not used; therefore, it is essential to validate its metric properties in future research to ensure its validity and reliability in a Latin American context. This will allow its applicability not only to COVID-19 but also to any cross-infection disease. Finally, it is recognized that, although these results cannot be extrapolated to the whole country, they can nevertheless be a starting point for developing studies in this line of research in order to identify gaps in knowledge and take appropriate measures to plan and reinforce training in disinfection as a means of controlling and reducing COVID-19 in professional dental practice.

It is recommended that university authorities, academic coordinators, and teachers re-evaluate and update disinfection protocols for infection control, as well as carry out training on this topic so that students can adequately develop their clinical practices and be prepared to continue to face COVID-19, since as of March 2023 it continues to claim lives, with 216,000 deaths reported daily worldwide and 87 deaths daily in Peru3. Furthermore, at present (January 2024), according to the Peruvian Ministry of Health, a cumulative case fatality rate of 4.85% and 220,632 deaths have been reported since the beginning of the pandemic50. On the other hand, research on cross-infection control and mitigation in dental students following a pandemic is recommended, as well as educational interventions on this topic to improve knowledge and attitudes in dental practice in the face of changes in public health policies, new scientific evidence, or possible epidemics or pandemics.

Conclusion

A minority of dental students had sufficient knowledge, while the majority had positive attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. In addition, being from the capital city was a limiting factor for sufficient knowledge. The variables sex, age, year of study, marital status, place of origin, death of a family member from COVID-19, and history of COVID-19 were not influential factors for positive attitudes on this topic. It is recommended that university authorities, academic coordinators, and teachers re-evaluate and update disinfection protocols so that students are prepared to face possible epidemics or pandemics. In addition, it is necessary to design and validate a standardized instrument to effectively assess knowledge and attitudes toward COVID-19 and other cross-infections adapted to the Latin American context.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (cesarcayorojas@gmail.com).

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

COronavirus DIsease 2019

- OSHA:

-

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- PPE:

-

Personal Protective Equipment

- PR:

-

Prevalence Ratio

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

References

Santome-Pariona, J. et al. Factors Associated with the level of knowledge about Biosafety against COVID-19 in Peruvian Dental students: a cross-sectional study under a multivariable regression model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (11), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115938 (2023).

Ministerio de Salud. Boletín Epidemiológico Semana Epidemiológica (del 17 al 23 de julio del 2022). (Accessed Jul 13, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://www.dge.gob.pe/epipublic/uploads/boletin/boletin_202229_19_114458.pdf

Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). COVID-19 Dashboard Peru. (Accessed Jul 13, 2023). (2023). Available from: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Naciones Unidas. Las infecciones de COVID-19 aumentan un 52% en un mes y se espera que la tendencia continúe. (Accessed Jan 15, 2024). (2024). Available from: https://news.un.org/es/story/2024/01/1526887

Sharaf, R. F. & Kabel, N. Awareness and knowledge of undergraduate dental students about the signs and symptoms of Corona viral infection (COVID-19), and the required infection control measures to prevent its spread. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 45 (32), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-021-00494-1 (2021).

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). (Accessed Jan 15, 2024). (2023). Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).

Newspaper. El Peruano. EsSalud: conozca las variantes causantes del covid-19 en el Perú. (Accessed Oct 15, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://www.elperuano.pe/noticia/140749-essalud-conoce-las-variantes-causantes-del-covid-19-en-peru

Newspaper. El Peruano. Más de 10 millones de personas ya recibieron la tercera dosis de vacuna. (Accessed Oct 15, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://elperuano.pe/noticia/140724-mas-de-10-millones-ya-tienen-la-dosis-de-refuerzo

Villani, F. A., Aiuto, R., Paglia, L. & Re, D. COVID-19 and Dentistry: Prevention in Dental Practice, a literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (12), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124609 (2020).

Amante, L. F. L. S., Afonso, J. T. M. & Skrupskelyte, G. Dentistry and the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. Dent. J. 71 (5), 358–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.identj.2020.12.010 (2021). 68.

Cayo-Rojas, C. F. & Baltazar-Sánchez, C. A. Dental clinical recommendations against COVID-19, according to scientific evidence. Rev haban cienc méd. ;19(2):e3283_E. (2020). Available from http://www.revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/3283

Morales-Montoya, M. et al. Psychological impact on dental students and professionals in a Lima population during COVID-19s wave: a study with predictive models. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 14752. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18899-x (2022).

Fiorillo, L. et al. COVID-19 Surface Persistence: A Recent Data Summary and Its Importance for Medical and Dental Settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;17(9):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093132 (2020).

Chatterjee, S., Murallidharan, J. S., Agrawal, A. & Bhardwaj R. Una revisión Sobre La Supervivencia Del coronavirus en superficies impermeables y porosas. Sadhanā 47 (5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-021-01772-4 (2022).

Roy, A., Parida, S. P. & Bhatia, V. Función de la desinfección y la higiene de manos: una perspectiva de COVID-19. Int. J. Community Med. Public. Health. 7 (7), 2845–2849. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20203025 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Optimizing Safe Dental Practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations based on a Guide developed for Dental practices in China. Front. Med. 8, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.619357 (2021).

Anandapadmanabhan, L. T. et al. Effect of COVID-19 on Dental Education. Rev. Cureus 2022, 14(4):1–8. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24455

Ministerio de Educación. Orientaciones para la implementación del retorno gradual a la presencialidad y/o semipresencialidad del servicio educativo superior universitario, en el marco de la emergencia sanitaria (RVM No. 015-2022-MINEDU). (Accessed Oct 17, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://www.minedu.gob.pe/conectados/pdf/orientaciones-semipresencialidad-resumen-2022.pdf

Romero-Saritama, J. M., Simaluiza, J. & Fernandez, H. Medidas de prevención para evitar el contagio por la COVID-19: de lo cotidiano a lo técnico-científico. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica. ;95:1–14. (2021). Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272021000100188

Von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the re-porting of Observational studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Gac Sanit. 22 (4), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1157/13119325 (2008).

Yang, J., Liao, Y., Hua, Q., Sun, C. & Lv, H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19: a cross-sectional study during normal management of the epidemic in China. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.913478 (2022).

Baker, I. et al. The Impacto f information sources on COVID-19- related knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) among University students: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (23), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312462 (2021).

Ahmed, M. N. Q., Lalin, S. A. A. & Ahmad, S. Factors affecting knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19: a study among undergraduate university students in Bangladesh. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 19 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2172923 (2023).

Larebo, Y. M. & Abame, D. E. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of face mask utilization and associated factors in COVID-19 pandemic among Wachemo University Students, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 16 (9), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257609 (2021).

Twinamasiko, N. et al. Assessing knowledge, attitudes and Practices towards COVID-19 Public Health Preventive Measures among Patients at Mulago National Referral Hospital. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. 14, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S287379 (2021).

Adli, I. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice related to the COVID-19 pandemic among undergraduate medical students in Indonesia: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 17 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262827 (2022).

Ding, Y. et al. Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its related factors among college students in China during quarantine. PLoS One. 15 (8), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237626 (2020).

Sarfaraz, S. et al. Knowledge and attitude of Dental Practitioners related to Disinfection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc. (Basel). 8 (3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030232 (2020).

Cayo-Rojas, C. F. et al. Level of knowledge about metalloproteinases in dental students close to graduate from three universities in Peruvian capital city. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 26 (4), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12748 (2022).

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310 (20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Hassan, M. G. & Amer, H. Dental Education in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and recommendations. Front. Med. 8, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.648899 (2021).

Das, A. et al. Implementation of infection prevention and control practices in an upcoming COVID-19 hospital in India: An opportunity not missed. PLoS One. 2022;17(5):1–13. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268071

Pathak, P. D. et al. Awareness and knowledge regarding Safety measures and Disinfection Protocols during Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic among Dental Students – A Questionnaire Survey. J. Indian Assoc. Public. Health Dent. 21 (2), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.4103/jiaphd.jiaphd_106_22 (2023).

Ministerio de Salud. De nosotros depende no bajar la guardia: la nueva campaña del Minsa para promover el cuidado contra la COVID-19. (accessed Nov 15, 2023). (2022). https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/612630-de-nosotros-depende-no-bajar-la-guardia-la-nueva-campana-del-minsa-para-promover-el-cuidado-contra-la-covid-19

Newspaper. La República. Así avanzó la vacunación contra la COVID-19 en Perú. (accessed Nov 15, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://data.larepublica.pe/avance-vacunacion-covid-19-peru/

Ministerio de Salud. Situación Actual COVID-19 Perú 2021–2022. (accessed Nov 15, 2023). (2022). Available from: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/tools/coronavirus/coronavirus310522.pdf

Golin, A. P., Choi, D. & Ghahary, A. Hand sanitizers: a review of ingredients, mechanisms of action, modes of delivery, and efficacy against coronaviruses. Am. J. Infect. Control. 48 (9), 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.182 (2020).

Al-Wutayd, O., Mansour, A. E., Aldosary, A. H., Hamdan, H. Z. & Al-Batanony, M. A. Handwashing knowledge, attitudes, and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a non-representative cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96393-6 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among undergraduate students in China. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09392-z (2020).

Umeizudike, K. A., Isiekwe, I. G., Fadeju, A. D., Akinboboye, B. O. & Aladenika, E. T. Nigerian undergraduate dental students’ knowledge, perception, and attitude to COVID-19 and infection control practices. J. Dent. Educ. 85 (2), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12423 (2020).

Zhang, W. & VanDyke, M. S. Association Versus Causation. In: (eds Schintler, L. A. & McNeely, C. L.) Encyclopedia of Big Data. Springer, Cham. :53–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32010-6_15 (2022).

Matamoros, R. A. & Ceballos, A. Errores conceptuales de estadística más comunes en publicaciones científicas. CES Med. Vet. Y Zootecnia. 12 (3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.21615/cesmvz.12.3.4 (2017).

Khan, S. A., Liew, M. L. & Oma, H. Role of ethical beliefs and attitudes of dental students in providing care for HIV/AIDS patients. Saudi Dent. J. 29 (1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2016.08.005 (2017).

Elsheikh, N. M. A. et al. Final year dental students’ perception and practice of professionalism and ethical attitude in ten Sudanese dental schools: a cross-sectional survey. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 9 (1), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_499_19 (2020).

Mamani-Benito, O. et al. Factores asociados a preocupación y miedo durante la COVID-19 en practicantes preprofesionales de salud. Rev. cuba. med. Mil. ;51(1):1–19 (2022). Available from: https://revmedmilitar.sld.cu/index.php/mil/article/view/1707

Ministerio de Salud. Manejo de la Atención Estomatológica en el Contexto de la Pandemia por COVID-19. 2020 (Accessed Sep 13, 2022). Available from: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/716209/DIRECTIVA_SANITARIA_N_100-MINSA-2020-DGIESP.pdf

Ataş, O. & Yildirim, T. T. Evaluation of knowledge, attitudes, and clinical education of dental students about COVID-19 pandemic. PeerJ 8, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9575 (2020).

Meng, L., Hua, F. & Bian, Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and Future challenges for Dental and oral medicine. J. Dent. Res. 99 (5), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520914246 (2020).

Gaffar, B. O. et al. Knowledge and practices of dentists regarding MERS-CoV A cross-sectional survey in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 40 (7), 714–720. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2019.7.24304 (2019).

Ministerio de Salud. Resumen de la situación del COVID 19 en el Perú al 13 de enero del 2024. (Accessed Jan 15, 2024). (2024). Available from: https://www.dge.gob.pe/covid19.html

Acknowledgements

We thank the Investigation Group “Grupo de Investigación en Salud Estomatológica (GISE)” of the School of Stomatology, Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista, Lima, Peru, for their constant support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Self-financed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S.R. conceived the research idea; G.S.R., G.B.V., M.L.C., E.H.H., P.G.C. and C.C.R elaborated the manuscript; G.S.R., R.A.A. and E.H.H. collected and tabulated the information; M.C.R., G.S.R., L.C.G., R.A.A. and P.G.C. carried out the bibliographic search; C.C.R. and M.L.C. interpreted the statistical results; G.S.R., M.L.C., G.B.V., L.C.G. and C.C.R. helped in the development from the discussion; R.A.A., M.C.R., P.G.C., L.C.G., and C.C.R. performed the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic approval and consent to participate

The present study adhered to the bioethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki related to respect, freedom, nonmaleficence, and confidentiality. Approval was obtained from an institutional ethics committee of the Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista whose resolution was No. 8-2022-CIEI-UPSJB dated January 17, 2022. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In addition, all participants gave their voluntary informed consent on the first page of the online questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva-Robles, G., Briceño-Vergel, G., Aroste-Andía, R. et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with dental students knowledge and attitudes regarding disinfection as a control measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Sci Rep 15, 2280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86155-z