Abstract

There are three Anopheles mosquito species in East Africa that are responsible for the majority of malaria transmission, posing a significant public health concern. Understanding the vector competence of different mosquito species is crucial for targeted and cost-effective malaria control strategies. This study investigated the vector competence of laboratory reared strains of East African An. gambiae sensu stricto, An. funestus s.s., and An. arabiensis mosquitoes towards local isolates of Plasmodium falciparum infection. Mosquito feeding assays using gametocytaemic blood from local donors revealed significant differences in both prevalence and intensity of oocyst and sporozoite infections among the three vectors. An. funestus mosquitoes presented the highest sporozoite prevalence 23.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) 17.5–29.6) and intensity of infection 6-58138 sporozoites. Relative to An. funestus, the odds ratio for sporozoites prevalence were 0.46 (95% CI 0.25–0.85) in An. gambiae and 0.19 (95% CI 0.07–0.51) in An. arabiensis, while the incidence rate ratio for sporozoite intensity was 0.31 (95% CI 0.14–0.69) in An. gambiae and 0.66 (95% CI 0.16–2.60) in An. arabiensis. Our findings indicate that all three malaria vector species may contribute to malaria transmission in East Africa, with An. funestus demonstrating superior vector competence. In conclusion, there is a need for comprehensive malaria control strategies targeting major malaria vector species, an update of malaria transmission models to consider vector competence and evaluation of malaria transmission blocking interventions in assays that include An. funestus mosquitoes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anopheles mosquitoes are the only arthropod vectors that transmit Plasmodium parasites that cause malaria in humans. The disease imposes a significant burden of mortality and morbidity, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)1 where the most efficient mosquito vectors of malaria are found2. Human malaria is mediated only by female Anopheles, and of the estimated 460 species, only 40 species or species complexes are considered to be important vectors in the wild3, notably the Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus species complexes that dominate malaria transmission throughout SSA4. In this paper, we focus on the three major East African vectors of human malaria: An. funestus sensu stricto, An. gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis.

The successful transmission of Plasmodium parasites between humans requires intricate transformations within the mosquito vector5, highlighting the key role of both vectorial capacity6 and vector competence7 in determining the local intensity of malaria transmission7.

Vector competence refers to the ability of an arthropod vector to acquire, maintain and transmit a pathogen. This concept encompasses the inherent ability of a pathogen to effectively enter and reproduce within the vector and be released from the vector’s salivary glands to initiate infection in another vertebrate host7,8. Vectorial capacity describes the potential intensity of transmission by mosquitoes. It is defined as the total number of infectious mosquito bites on humans that will arise from a single infected person on a single day9. This is influenced by a number of factors6,10, most notably the probability of mosquitoes to feed on humans11, daily vector survival12, environmental factors that affect the time it takes for parasites to develop in the mosquito host13, the availability of larval breeding sites14, presence of vector control tools10 and vector competence15.

The vectoral capacity of a particular vector is strongly influenced by its ecology. The larval stage of mosquitoes takes place in water where biological factors greatly influence the habitat suitability and carrying capacity. These factors influence vector presence3, fitness16, longevity17, which in turn affects the probability that a mosquito can acquire and maintain a parasite for long enough to become infectious18. In East Africa, the three major vectors have different regional distribution due to ecology19 and hydrology14 and varying contributions to malaria transmission across different seasons20,21,22,23. An. funestus mosquitoes have permanent breeding sites abundant with vegetation, making them likely to transmit malaria all year round24,25. An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. typically dominate in temporary sunlit pools and their presence is strongly dependent on rainfall or irrigation26,27. An. gambiae s.s. requires high humidity to survive and occurs almost exclusively during humid and rainy periods28. An. arabiensis and An. funestus, are more resistant to desiccation, are commonly found in abundance during the peak of the wet season and continue into the dry season; sustaining malaria transmission for several months after the end of the rains23,29.

Anopheles mosquitoes are dependent on vertebrate blood to provide proteins needed for egg development and undergo multiple cycles of feeding and egg development in their lifetime. Therefore, the preference of a vector for human blood has a direct impact on its efficiency as a vector by increasing its probability of acquiring and transmitting onward infection30. An. arabiensis have an opportunistic feeding behavior, targeting both human and animal hosts for its blood meals, so it may be a more or less important vector dependent on the relative proportion of cattle in an area31. An. gambiae s.s.32,33 and An. funestus34,35 are more specialized blood feeders, feeding on humans, although this does depend on host availability. In addition, there is evidence that multiple blood meals increase the likelihood of Plasmodium developing in the mosquito36,37.

As well as environmental factors that affect vectors’ susceptibility to infection and the interactions between the vector, pathogen, and host that impact probabilities of onward transmission, vector competence is influenced by a variety of internal factors, including the genetics of both the vector and the pathogen5,38. Plasmodium takes resources from its definitive host that results in reduced fitness and reproductive output39. Therefore, the mosquito innate immune system either modulates or resists infection40, while the parasite counteracts mosquito defenses through host manipulation41 and polyclonality42. Mosquito species show different levels of susceptibility to Plasmodium from refractory in the case of Anopheles quadriannulatus43,44 to high susceptibility in Anopheles coluzzi45,46.

In East Africa, there is evidence of higher proportions of infected An. funestus47,48 relative to An. arabiensis and An. gambiae. This can be to an extent explained by the fact that An. funestus generally feeds almost exclusively on humans and has been shown to live longer than An. arabiensis49. However, any differences in degree of vector competence among the three primary malaria vectors has not been evaluated. Understanding vector competence is crucial in understanding the risk of malaria transmission, informing effective malaria control strategies38,50,51 and parameterizing mathematical models, where mosquito-parasite interactions are rarely considered15,52.

Therefore, this study investigated whether vector competence towards Plasmodium falciparum differs between local East African strains of An. gambiae s.s., An. funestus and An. arabiensis mosquitoes. By experimentally infecting mosquitoes with field gametocytes using Direct Membrane Feeding Assays (DMFAs), we aim to compare the prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum infection between these Anopheles mosquito species.

Results

Prevalence and intensity of P. falciparum infection among local strains of An. gambiae s.s., An. funestus and An. arabiensis mosquitoes

Oocysts

The prevalence of oocyst-infected mosquitoes varied among the three Anopheles mosquito species, with An. funestus presenting the highest oocyst infection rate of 13.5% (95% CI 9.2–17.6), followed by An. gambiae s.s. at 10.7% (95% CI 6.9–14.4), and An. arabiensis at 5.6% (95% CI 2.5–8.7) (Table 1). The proportion of oocyst-infected An. arabiensis mosquitoes was significantly lower than An. funestus mosquitoes (OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.20–0.80, p = 0.010), but there was no difference between An. funestus and An. gambiae (Fig. 1A). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the proportion of oocyst-infected mosquitoes between An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis mosquitoes (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.25–1.06, p = 0.072). There was no significant difference in oocyst intensity between the three species, although as with prevalence, oocyst intensity was similar between An. funestus, ranging from 1 to 12 and An. gambiae s.s., ranging from 1 to 14; and it was lower in An. arabiensis, ranging from 1 to 3 (Fig. 1C). The oocyst infection prevalence from DMFAs for each gametocyte carrier, along with the corresponding gametocyte densities, is displayed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Sporozoites

The burden of sporozoite-infected mosquitoes varied among the three Anopheles mosquito species, with An. funestus presenting the highest sporozoite infection rate of 23.5% (95% CI 17.5–29.6), followed by An. gambiae s.s. at 11.4% (95% CI 6.5–16.3), and An. arabiensis at 4.9% (95% CI 0.6–9.1) (Table 1). An. funestus had a higher probability of being sporozoite-infected than An. gambiae s.s. (OR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.25–0.85, p = 0.013) or An. arabiensis (OR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.07–0.51, p = 0.001), (Fig. 1B). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference observed in the proportion of sporozoite infection between An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis mosquitoes (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.14–1.17 P = 0.098), although there were few infected An. arabiensis. Additionally, there were similar trends observed in sporozoite intensity among the three species, with highest intensity observed in An. funestus, ranging from 6 to 58,138 followed by An. gambiae s.s., ranging from 21 − 7,976 and An. arabiensis ranging from 20 to 27,877. A significant difference was observed in sporozoite intensity between An. funestus and An. gambiae s.s. (IRR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.14–0.69, p = 0.004) (Fig. 1D), although not between An. funestus and An. arabiensis likely due to low sporozoite prevalence (5%) in An. arabiensis leading to uncertainty in the estimates. The sporozoite infection prevalence from DMFAs for each gametocyte carrier, along with the corresponding gametocyte densities, is displayed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Discussion

This study represents the first attempt to measure whether the degree of vector competence towards P. falciparum infection varies between East African An. funestus s.s., An. arabiensis, and An. gambiae s.s. mosquitoes. Through experimental feeding of mosquitoes with gametocytaemic blood from donors in Tanzania, we observed significant differences in both prevalence and intensity of oocyst and sporozoite infections among An. gambiae s.s., An. funestus s.s., and An. arabiensis mosquitoes. An. funestus s.s. mosquitoes presented with the highest prevalence and intensity of infection indicating that they are more competent than either An. gambiae s.s. or An. arabiensis. This is the first time, to our knowledge that the vector competence of An. funestus s.s. has been evaluated. The findings of this study largely agreed with the findings of a study in Burkina Faso, that found no difference in genetic susceptibility to P. falciparum measured by oocyst infection between three sympatric population groups of the An. gambiae s.l. complex including An. coluzzi, An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis that had been reared from wild-caught larvae46.

Anopheles mosquitoes are reported to have varying levels of vector competence, influenced by genetic factors, as well as environmental conditions, and host-parasite interactions5,38,53. An. gambiae s.s. has long been recognized as a highly polymorphic and efficient malaria vector, possibly due to the strong co-adaptation of P. falciparum to this specific mosquito species54. However, our study reveals that An. funestus were more competent. This finding is consistent with reports of increasing malaria cases caused by An. funestus in Tanzania and other parts of SSA55,56,57,58,59. The high prevalence and intensity of infection observed in An. funestus mosquitoes suggest its potential as a predominant malaria vector, particularly in areas with suitable breeding sites abundant in vegetation. Our results are consistent with the observation that the massive introgression event that lead to the evolution of An. funestus 13,000 years ago that facilitated its adaptation to new environments resulting in its subsequent dramatic geographic range expansion across most of tropical Africa also enhanced vectorial capacity in Anopheles funestus mosquitoes60.

Although An. arabiensis mosquitoes play a crucial role in malaria transmission, particularly in arid regions in the Horn of Africa47, our findings show lower prevalence and intensity of oocyst and sporozoite infections when compared to An. funestus and An. gambiae s.s. mosquito infections. While An. arabiensis is often abundant, and is widely discussed as a vector of residual and outdoor malaria, the more competent and endophilic malaria vectors An. funestus s.s. and An. gambiae s.s. should be targeted for control.

While several studies have shown that insecticide resistant vectors are more competent to Plasmodium61,62, our study also found that An. funestus mosquitoes which are resistant to pyrethroids showed increased susceptibility to Plasmodium infection. The susceptibility of mosquitoes to Plasmodium infection may result from either their increased survival and longevity63 compared to susceptible mosquitoes, which are killed by insecticide64, or could be due to reduced immunity to parasites65. Therefore, we cannot rule out that the difference in insecticide susceptibility affected the results through a change in mosquito immunity to parasites. There is strong evidence suggesting that insecticide resistance mutations increase the vector competence of An. gambiae for Plasmodium, potentially sustaining malaria transmission62. However, the An. arabiensis used in the study were also pyrethroid resistant and were still relatively less susceptible to infection.

An additional study has shown that insecticide resistance mechanisms have an effect on the activation of the mosquito immune system and its physiology, resulting in differences in parasite development and survival66. Variations in parasite burden may not significantly affect parasite transmission, however, the intensity of infection does influence the activation of the vector immune system67. Nonetheless, in our study, all three species showed susceptibility to Plasmodium infection, with An. funestus presenting a higher susceptibility compared to An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis. It was suggested that the susceptibility of An. gambiae to Plasmodium infection is due to persistent immune suppression to prevent excessive activation of the immune response following blood meal ingestion68. Moreover, research has shown that genetic diversity within mosquito populations can also significantly influence their susceptibility to Plasmodium infection69.

This study highlighted that, while An. gambiae mosquitoes are commonly used in DMFAs to assess different malaria transmission-blocking interventions70,71,72, the observed shift towards An. funestus as a major contributor to transmission in SSA58, with the highest infection burden, suggests the importance of incorporating An. funestus mosquitoes into assays for testing malaria transmission-blocking activity. Our study has several limitations. First, it exclusively used laboratory-reared mosquito strains rather than field-collected mosquitoes. Second, the An. funestus (FUMOZ) mosquitoes used in the study were originally collected and colonized in Mozambique, reflecting the challenges associated with colonizing An. funestus in insectaries. Thirdly, we did not record mosquito survival from day 1 to day 16 post-infection, although only live mosquitoes were dissected so prevalence and incidence is among those mosquitoes that survived the extrinsic incubation period. Lastly, the study was limited by the relatively small number of gametocytemic individuals, attributable to reduced rainfall during the year 2023, which led to few gametocyte-infected individuals. This aligns with observations from other studies in the same region, which also reported comparably low gametocyte counts37,73,74. To address this limitation, future studies should focus on recruiting a larger number of gametocytemic participants.

In conclusion, we confirmed that between the three mosquito species, An. funestus was the most permissive to P. falciparum infection, which is coherent with consistently high sporozoite rates observed in this species across SSA, whereas An. arabiensis shows the greatest resistance coherent with its lower observed sporozoites rates. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that all the three vector species play an active role in malaria transmission. The observed differences in vector competence among the three Anopheles species highlight the complexity of malaria transmission dynamics and the need for comprehensive malaria control strategies that target key malaria vector species. Furthermore, malaria transmission models should be revised to account for vector competence, and efforts to support malaria transmission blocking interventions tested on multiple malaria vectors are essential for making sustainable progress towards malaria elimination.

Methods

Mosquito rearing

An. gambiae s.s. mosquitoes were originally collected from the southern region of Tanzania (Njage-Mngeta villages, Ifakara district, Morogoro region) in 1996 and have been maintained at the Ifakara Health Institute (IHI) insectaries, Tanzania. This strain of Anopheles gambiae s.s. is susceptible to all classes of insecticides. Field-collected An. arabiensis mosquitoes were obtained from the southern region of Tanzania (Sakamaganga village, Ifakara district) in 2005 and have been maintained in IHI insectaries. This strain is resistant to pyrethroids at a 1× discriminating concentration and is susceptible to other classes. The An. funestus colony at the IHI insectaries was established in 2018 and originates from a founder colony initially established in 2000 in Matola province75, southern Mozambique, where pyrethroid resistance had been documented in the wild population. The eggs used to establish the IHI colony were obtained from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) in South Africa. This strain is resistant to pyrethroids at a 1× discriminating concentration and is susceptible to other classes. Mosquito larvae were maintained at a density of 200 larvae per litre of water and fed 0.3 g per larva on Tetramin fish food (Tetra Ltd., UK). For colony maintenance, the adult mosquitoes are provided with cow blood between 3 and 6 days after emergence for egg development using a Hemotek® membrane feeder (SP-6 System, Hemotek Ltd., Blackburn BB6 7FD, UK). Mosquitoes were provided with autoclaved 10% sucrose solution ad libitum. Temperature and humidity within the insectary are maintained between 27 ± 2 °C and 60–85% relative humidity following the MR4 guidance76.

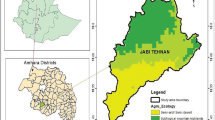

Recruitment of asymptomatic gametocytaemic carriers

Gametocytaemic carriers were selected by screening thick blood smears from participants aged 6–40 years located in the village of Wami-Mkoko, in Bagamoyo district located in the coastal region of Tanzania, between June 2023 and August 2023. Participants meeting the inclusion criteria (asymptomatic individuals aged 6–40 who consented and had microscopically detectable gametocytes) were enrolled for blood collection at IHI transmission facilities in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.

Gametocytes were quantified by counting against 500 white blood cells in thick smears, and their density was calculated based on an estimated leukocyte density of 8000/µL of whole blood. Five milliliters of blood were obtained from microscopically confirmed gametocyte carriers with gametocytes density exceeding three gametocytes/500 red blood cells, equivalent to 48 gametocytes/ µL of whole blood. Seven gametocytaemic individuals were recruited to donate blood to feed all three mosquito species during each DMFA. Autologous serum was replaced with pre-warmed malaria-naïve AB serum European donors.

Experimental infection of P. falciparum in Anopheles mosquitoes through DMFAs

Infectious gametocytaemic blood was administered to mosquitoes through water-jacketed glass feeders (14 mm Ø, Chemglass, New Jersey, USA) covered with parafilm®, connected to a circulating water bath (39,°C, ELMI, Switzerland) via plastic tubing. On average, 200 mosquitoes from each mosquito strain were fed a blood meal from each participant for a duration of 15 min. After blood feeding, the cups containing mosquitoes were then transferred to Bugdorm plastic cages (30 cm x 30 cm x 30 cm, Megaview Science Co., LTD, Taiwan) and placed in a climatic chamber (S600PLH, AraLab, Lisbon, Portugal) maintained at 75 ± 2% humidity and 27 ± 1 °C at 12:12 h dark: light cycle. Mosquitoes were deprived of sugar for 48 h to allow unfed mosquitoes to die, so only fed mosquitoes were used. Dead mosquitoes were aspirated out after 48 h and then cotton soaked with autoclaved 10% sucrose solution was provided and replaced daily.

Oocyst and sporozoite scoring

Eight days’ post infection (dpi), one-third of mosquitoes from each mosquito strain was dissected and their midguts were stained with a 1% mercurochrome solution before examination for presence of oocysts microscopically. The remaining mosquitoes were kept up to day 16 dpi and the mosquito`s DNA was extracted using DNAzol® reagent77 for molecular analysis and quantification of P. falciparum infection in mosquito stages from the mosquito heads and thoraces (sporozoites stages). Using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)78, absolute quantification of all sporozoites positive samples was performed using the standard curves generated on P. falciparum-specific 18 S rDNA plasmid (GenBank: AF145334) from P. falciparum (BEI Resources, NIAID, MRA-177). Plasmid copy numbers per µl were calculated as described elsewhere79. The standard curves were generated on serial dilutions over eight magnitudes assuming an average of six copies of the 18 S rDNA gene sequence per parasite genome80. Each concentration from the serial dilution was run in triplicates to determine qPCR efficiency, limit of detection, slope and y-intercept.

Statistical analysis

Data cleaning and analysis were conducted using STATA 17 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were employed for data summarization, presenting the proportion of infected mosquitoes with a 95% confidence interval. For parasite intensity (oocysts or sporozoites), the median along with minimum and maximum values were reported.

To evaluate vector competence towards P. falciparum infection among the three mosquito strains, mixed-effect regression was used, with mosquito strain as a fixed categorical effect and study participants included as a random effect. For oocyst and sporozoite prevalence logistic distribution was used. For oocyst and sporozoite intensity, negative binomial distribution was used and only infected mosquitoes were included in the intensity analysis.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

WHO. The World Malaria Report 2023 (World Health Organization, 2023).

Kiszewski, A. et al. A global index representing the stability of malaria transmission. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70, 486–498 (2004).

Sinka, M. E. et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit. Vectors. 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-69 (2012).

Sinka, M. E. et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic precis. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-3-117 (2010).

Lefevre, T., Vantaux, A., Dabire, K. R., Mouline, K. & Cohuet, A. Non-genetic determinants of mosquito competence for malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003365 (2013).

Wu, S. L. et al. Vector bionomics and vectorial capacity as emergent properties of mosquito behaviors and ecology. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1007446. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007446 (2020).

Cohuet, A., Harris, C., Robert, V. & Fontenille, D. Evolutionary forces on Anopheles: what makes a malaria vector? Trends Parasitol. 26, 130–136 (2010).

Reeves, W. C., Asman, S., Hardy, J., Milby, M. & Reisen, W. Epidemiology and control of mosquito-borne arboviruses in California, 1943–1987. (1990).

Garrett-Jones, C. & Grab, B. The assessment of insecticidal impact on the malaria mosquito’s vectorial capacity, from data on the proportion of Parous females. Bull. WHO 31 (1964).

Brady, O. J. et al. Vectorial capacity and vector control: reconsidering sensitivity to parameters for malaria elimination. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 110, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trv113 (2016).

Garrett-Jones, C. The human blood index of malaria vectors in relation to epidemiological assessment. Bull. World Health Organ. 30 (1964).

Matthews, J., Bethel, A. & Osei, G. An overview of malarial Anopheles mosquito survival estimates in relation to methodology. Parasit. Vectors. 13, 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04092-4 (2020).

Ohm, J. R. et al. Rethinking the extrinsic incubation period of malaria parasites. Parasites Vectors. 11, 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2761-4 (2018).

Smith, M. W. et al. Incorporating hydrology into climate suitability models changes projections of malaria transmission in Africa. Nat. Commun. 11, 4353. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18239-5 (2020).

Smith, D. L. et al. Ross, Macdonald, and a theory for the dynamics and control of mosquito-transmitted pathogens. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002588 (2012).

Okech, B. A., Gouagna, L. C., Yan, G., Githure, J. I. & Beier, J. C. Larval habitats of Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) influences vector competence to Plasmodium falciparum parasites. Malar. J. 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-6-50 (2007).

Asmare, Y., Hopkins, R. J., Tekie, H., Hill, S. R. & Ignell, R. Grass pollen affects survival and development of larval Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Insect Sci. (Online). 17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iex067 (2017).

Shapiro, L. L., Murdock, C. C., Jacobs, G. R., Thomas, R. J. & Thomas, M. B. Larval food quantity affects the capacity of adult mosquitoes to transmit human malaria. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283 https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0298 (2016).

Schapira, A. & Boutsika, K. Malaria ecotypes and stratification. Adv. Parasitol. 78, 97–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394303-3.00001-3 (2012).

Takken, W. & Lindsay, S. W. Factors affecting the vectorial competence of Anopheles gambiae: a question of scale. In Ecol. Aspects Application Genetically Modified Mosquitoes, 75–90 (Kluwer Acad. Publishers, 2003).

Villena, O. C., Ryan, S. J., Murdock, C. C. & Johnson, L. R. Temperature impacts the environmental suitability for malaria transmission by Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles Stephensi. Ecology 103, e3685 (2022).

Moller-Jacobs, L. L., Murdock, C. C. & Thomas, M. B. Capacity of mosquitoes to transmit malaria depends on larval environment. Parasit. Vectors. 7, 1–12 (2014).

Charlwood, J. D. et al. The rise and fall of Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae) in a Tanzanian village. Bull. Entomol. Res. 85, 37–44 (1995).

Mendis, C. et al. Anopheles arabiensis and an. Funestus are equally important vectors of malaria in Matola coastal suburb of Maputo, southern Mozambique. Med. Vet. Entomol. 14, 171–180 (2000).

Nambunga, I. H. et al. Aquatic habitats of the malaria vector Anopheles Funestus in rural south-eastern Tanzania. Malar. J. 19, 1–11 (2020).

Lindsay, S. et al. Exposure of Gambian children to Anopheles gambiae malaria vectors in an irrigated rice production area. Med. Vet. Entomol. 9, 50–58 (1995).

Gillies, M. T. & Coetzee, M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ S Afr. Inst. Med. Res. 55, 1–143 (1987).

Mala, A. O. et al. Dry season ecology of Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes at larval habitats in two traditionally semi-arid villages in Baringo, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors. 4, 1–11 (2011).

Mwanziva, C. E. et al. Transmission intensity and malaria vector population structure in Magugu, Babati District in northern Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 13, 54–61 (2011).

Smith, D. L. & McKenzie, F. E. Statics and dynamics of malaria infection in Anopheles mosquitoes. Malar. J. 3, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-3-13 (2004).

Kent, R. J., Thuma, P. E., Mharakurwa, S. & Norris, D. E. Seasonality, blood feeding behavior, and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum by Anopheles arabiensis after an extended drought in southern Zambia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76, 267 (2007).

Lyimo, I. N., Keegan, S. P., Ranford-Cartwright, L. C. & Ferguson, H. M. The impact of uniform and mixed species blood meals on the fitness of the mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae s.s: does a specialist pay for diversifying its host species diet? J. Evol. Biol. 25, 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02442.x (2012).

Takken, W. & Verhulst, N. O. Host preferences of blood-feeding mosquitoes. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 58, 433–453 (2013).

Kahamba, N. F. et al. Using ecological observations to improve malaria control in areas where Anopheles Funestus is the dominant vector. Malar. J. 21, 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04198-3 (2022).

Sinka, M. E. et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 1–34 (2010).

Shaw, W. R. et al. Multiple blood feeding in mosquitoes shortens the Plasmodium falciparum incubation period and increases malaria transmission potential. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1009131 (2020).

Hofer, L. M. et al. Additional blood meals increase sporozoite infection in Anopheles mosquitoes but not Plasmodium falciparum genetic diversity. Sci. Rep. 14, 17467 (2024).

Beerntsen, B. T., James, A. A. & Christensen, B. M. Genetics of mosquito vector competence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 115–137 (2000).

Hajkazemian, M., Bossé, C., Mozūraitis, R. & Emami, S. N. Battleground midgut: the cost to the mosquito for hosting the malaria parasite. Biol. Cell. 113, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/boc.202000039 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Response of the mosquito immune system and symbiotic bacteria to pathogen infection. Parasit. Vectors. 17, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06161-4 (2024).

Emami, S. N. et al. A key malaria metabolite modulates vector blood seeking, feeding, and susceptibility to infection. Science 355, 1076–1080. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah4563 (2017).

Nsango, S. E. et al. Genetic clonality of Plasmodium falciparum affects the outcome of infection in Anopheles gambiae. Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.03.008 (2012).

Takken, W. et al. Susceptibility of Anopheles Quadriannulatus Theobald (Diptera: Culicidae) to Plasmodium falciparum. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93, 578–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90054-8 (1999).

Habtewold, T., Povelones, M., Blagborough, A. M. & Christophides, G. K. Transmission blocking immunity in the malaria non-vector mosquito Anopheles Quadriannulatus species a. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000070. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000070 (2008).

Habtewold, T., Groom, Z. & Christophides, G. K. Immune resistance and tolerance strategies in malaria vector and non-vector mosquitoes. Parasit. Vectors. 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2109-5 (2017).

Gnémé, A. et al. Equivalent susceptibility of Anopheles gambiae M and S molecular forms and Anopheles arabiensis to Plasmodium falciparum infection in Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 12, 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-204 (2013).

Aschale, Y. et al. Systematic review of sporozoite infection rate of Anopheles mosquitoes in Ethiopia, 2001–2021. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 437. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-06054-y (2023).

Kabula, B. et al. Malaria entomological profile in Tanzania from 1950 to 2010: a review of mosquito distribution, vectorial capacity and insecticide resistance. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 13, 319–331 (2011).

Ntabaliba, W. et al. Life expectancy of Anopheles Funestus is double that of Anopheles arabiensis in southeast Tanzania based on mark-release-recapture method. Sci. Rep. 13, 15775. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42761-3 (2023).

Brady, O. J. et al. Vectorial capacity and vector control: reconsidering sensitivity to parameters for malaria elimination. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 110, 107–117 (2016).

Shaw, W. R. & Catteruccia, F. Vector biology meets disease control: using basic research to fight vector-borne diseases. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 20–34 (2019).

Reiner, R. C. Jr. et al. A systematic review of mathematical models of mosquito-borne pathogen transmission: 1970–2010. J. R Soc. Interface. 10, 20120921. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0921 (2013).

Barreaux, A. M., Barreaux, P., Thievent, K. & Koella, J. C. Larval environment influences vector competence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Malar. World J. 7, 1–6 (2016).

White, B. J., Collins, F. H. & Besansky, N. J. Evolution of Anopheles gambiae in relation to humans and malaria. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 111–132 (2011).

Lwetoijera, D. W. et al. Increasing role of Anopheles Funestus and Anopheles arabiensis in malaria transmission in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Malar. J. 13, 1–10 (2014).

Matowo, N. S. et al. An increasing role of pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles funestus in malaria transmission in the Lake Zone, Tanzania. Sci. Rep. 11, 13457 (2021).

Ogola, E. O., Odero, J. O., Mwangangi, J. M. & Masiga, D. K. Tchouassi, D. P. Population genetics of Anopheles Funestus, the African malaria vector, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 1–9 (2019).

Msugupakulya, B. J. et al. Changes in contributions of different Anopheles vector species to malaria transmission in east and southern Africa from 2000 to 2022. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 408 (2023).

Wangrawa, D. W., Odero, J. O., Baldini, F., Okumu, F. & Badolo, A. Distribution and insecticide resistance profile of the major malaria vector Anopheles Funestus group across the African continent. Med. Vet. Entomol. 38, 119–137 (2024).

Small, S. T. et al. Radiation with reticulation marks the origin of a major malaria vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.. 117, 31583–31590. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2018142117 (2020).

Suh, P. F. et al. Impact of insecticide resistance on malaria vector competence: a literature review. Malar. J. 22, 19 (2023).

Alout, H. et al. Insecticide resistance alleles affect vector competence of Anopheles gambiae Ss for Anopheles gambiae field isolates. PLoS One. 8, e63849 (2013).

Barreaux, P., Koella, J. C., N’Guessan, R. & Thomas, M. B. Use of novel lab assays to examine the effect of pyrethroid-treated bed nets on blood-feeding success and longevity of highly insecticide-resistant Anopheles gambiae Sl mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors. 15, 111 (2022).

Minetti, C., Ingham, V. A. & Ranson, H. Effects of insecticide resistance and exposure on Plasmodium development in Anopheles mosquitoes. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 39, 42–49 (2020).

James, R. & Xu, J. Mechanisms by which pesticides affect insect immunity. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 109, 175–182 (2012).

Rivero, A., Vezilier, J., Weill, M., Read, A. F. & Gandon, S. Insecticide control of vector-borne diseases: when is insecticide resistance a problem? PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001000 (2010).

Mendes, A. M. et al. Infection intensity-dependent responses of Anopheles gambiae to the African malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Infect. Immun. 79, 4708–4715 (2011).

Cirimotich, C. M., Ramirez, J. L. & Dimopoulos, G. Native microbiota shape insect vector competence for human pathogens. Cell. host Microbe. 10, 307–310 (2011).

Harris, C. et al. Plasmodium falciparum produce lower infection intensities in local versus foreign Anopheles gambiae populations. PloS One. 7, e30849 (2012).

Henry, B. Assessment of the transmission blocking activity of antimalarial compounds by membrane feeding assays using natural Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte isolates from West-Africa. PLoS One. 18, e0284751 (2023).

Kweyamba, P. A. et al. Sub-lethal exposure to chlorfenapyr reduces the probability of developing Plasmodium falciparum parasites in surviving Anopheles mosquitoes. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 342 (2023).

Habtewold, T. et al. Streamlined SMFA and mosquito dark-feeding regime significantly improve malaria transmission-blocking assay robustness and sensitivity. Malar. J. 18, 1–11 (2019).

Hofer, L. M. et al. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests reliably detect asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infections in school-aged children that are infectious to mosquitoes. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 217 (2023).

Mulamba, C. et al. Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte burden in a Tanzanian low transmission setting. (2024).

Hunt, R., Brooke, B., Pillay, C., Koekemoer, L. & Coetzee, M. Laboratory selection for and characteristics of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 19, 271–275 (2005).

Benedict, M. (2018).

Chomczynski, P., Mackey, K., Drews, R. & Wilfinger, W. DNAzol®: a reagent for the rapid isolation of genomic DNA. Biotechniques22, 550–553 (1997).

Schindler, T. et al. Molecular monitoring of the diversity of human pathogenic malaria species in blood donations on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar. J. 18, 1–11 (2019).

Whelan, J. A., Russell, N. B. & Whelan, M. A. A method for the absolute quantification of cDNA using real-time PCR. J. Immunol. Methods. 278, 261–269 (2003).

Mercereau-Puijalon, O., Barale, J. C. & Bischoff, E. Three multigene families in Plasmodium parasites: facts and questions. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 1323–1344 (2002).

Health, M. & Welfare, S. (United Republic of Tanzania Dar es Salam, 2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the village leaders and community in Bagamoyo for their unwavering cooperation and support throughout the study. A special thanks to Vector Control and Product Testing Unit (VCPTU) management, administrators and colleagues who helped in organising logistics and materials, allowing smooth performance of the study.

Funding

This study`s field work was funded by VCTPU and PAK, RYM, RMS and FM receive salary support from the Transmission Zero project (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), grant no. OPP1158151).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.M., P.A.K., M.M.T., L.H. conceived the study. P.A.K., L.H. and M.M.T. developed the study protocol. R.Y.M. and P.A.K. performed the mosquito feeding assays. R.M.S., P.A.K. and F.M. dissected the mosquitoes. P.A.K., L.H. and R.Y.M. performed molecular analysis. P.A.K. drafted the manuscript. S.J.M., M.M.T., D.W.L., and L.H. reviewed and edited drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All adult participants provided written informed consent, while for children under 18 years old, consent was obtained from their parent or guardian, with the children’s assent also sought for their participation. All study volunteers received artemisinin-lumefantrine treatment within 24 h of diagnosis, following the Tanzania Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria81, administered by a qualified nurse. No adverse effects were reported among the participants during the study period. The study activities were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of IHI (IHI/IRB/No: 44–2020) and the National Institute for Medical Research Tanzania (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/3595). All research was performed in accordance to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kweyamba, P.A., Hofer, L.M., Kibondo, U.A. et al. Contrasting vector competence of three main East African Anopheles malaria vector mosquitoes for Plasmodium falciparum. Sci Rep 15, 2286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86409-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86409-w