Abstract

In nature conservation, ex situ and in situ conservation strategies are discussed for protecting endangered species of plants and animals. However, the impacts of these strategies on the microbes associated with these species are rarely considered. In our study, we chose the endophytic fungi of the pantropical creeping plant Ipomoea pes-caprae as representative coastal plant in two natural coastal populations and two botanical gardens in Taiwan as collection sites in order to investigate the potential effect of ex situ plantation on the biodiversity of microbes intimately associated with this plant. In a culture-dependent approach, endophytic fungi were isolated under axenic conditions and identified to species, genus, or higher taxonomic ranks with DNA barcodes and morphology. In addition to yielding ca. 800 strains and over 100 morphospecies, a principal component analysis (PCA) of the distribution of the dominant fungal species showed clear differences in the composition of endophytic fungal species depending on the sampling sites. We conclude that the endophytic fungi from the original site are replaced by other species in the ex situ plantations. Due to the limitations of ex situ conservation of microbes and from a mycological and microbial perspective, in situ conservation should outweigh ex situ approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As specialized habitats, sandy beaches are characterized by extremes of inundation and drought, lack of nutrients, high salinity, strong wind movement, sand burial, and solar irradiation1. Due to the geomorphology in Taiwan, the natural habitat of sand coasts is restricted to mainly the northern and western parts. Herbaceous vegetation at sand coasts consists of specific plants which include many plants that do not occur inland, because they are outcompeted by other plants under more favorable growth conditions, and is, therefore, important for coast protection and preventing erosion1. Recent research indicated that the ability of coast protection and preventing erosion provided by plants depends on differences in plant architecture2. Among common coastal plants, Ipomoea pes-caprae (Fig. 1) is pantropically distributed and the most effective species for protection because it covers the sand by stems and leaves like a carpet2. Ipomoea pes-caprae is also one of the most common and most widely distributed salt-tolerant plants in sandy beaches of Taiwan3.

Endophytic fungi grow within healthy plant tissues for all or part of their life cycle without obvious symptoms4. Endophytic fungi are important components of fungal biodiversity. Now about 120,000 fungal species are known, comprising ca. 5% of the total estimated 2.2 million species on this planet5. This estimation is also due to the fact that fungal endophytes have been isolated from all plant species investigated so far. The potential of endophytic fungi as sources for bioactive compounds and drug development, such as taxol in chemotherapy6 has been largely exaggerated, since the claims of taxol production by endophytic fungi have been rejected and in the market the anthelmintic cyclodepsipeptide PF1022A and the antifungal Ibrexafungerp seem to be the single products derived from fungi which can be isolated as endophytes7,8. This mere potential, however, initiated an increase of studies about endophytic fungi significantly. According to the interactions between endophytic fungi and their host plants, some fungi are latent pathogens, others are only saprobic commensals, and another group of fungi provide benefits to their host plants9,10. For most endophytes, however, the roles they play for their host plants are not known.

In traditional biological conservation, we focus on the individual animal or plant species, without consideration of the microorganisms associated with this species from a special habitat11,12,13. For example, when a habitat is destroyed, its endangered plant species can be preserved ex situ in botanical gardens. The fate of microbes associated with this plant, however, has not been investigated in a comparative study. In the different strategies of conservation of plant and fungus species, conservation of fungi is underrepresented and usually focused on ex situ preservation14. There are several major botanical gardens and numerous smaller ones but only one professional fungal culture collection in Taiwan (see below). Certain ecologically important or species-rich groups of fungi cannot be cultivated14,15. Likewise, certain groups of herbaceous plants (Asteraceae, Poaceae) are also less preserved in botanical gardens than more showy or woody plants15. Herbaceous coastal plants, therefore, are not often cultivated in botanical gardens, except for I. pes-caprae (see below). Here we choose endophytic fungi of I. pes-caprae as an example of plant-associated fungi and microbes in general. Endophytic fungi have been shown to confer salt, heat, and drought tolerance to plants growing under stress conditions, though the mechanisms for this effect are unknown16,17. As transcriptomic studies have shown, increase of plant defense-related gene expression is correlated with increased pathogen resistance18. The causative connections, however, have not yet been clarified. From the literature about endophytes, we hypothesize that the specific locality plays a role being at least as important as the plant species with respect to the specificity of fungal species17. Generally, studies of endophytic fungi of coastal plants were mainly undertaken in Europe but few is known about the endophytes of tropical/subtropical coastal herbaceous plants19. Because of different climates and other factors, the plant species differ considerably between temperate and tropical/subtropical coasts20. To our knowledge, studies about the impact of in situ and ex situ conservation of host plants on the biodiversity of endophytic fungi have not yet been undertaken. Comparing endophytes of coastal plants from the natural habitat with those from artificial plantations is a novel approach for evaluating the potential impact of in situ and ex situ conservation of host plants on the biodiversity of endophytic fungi and microbes in general. We, therefore, intend to compare endophytes of I. pes-caprae from natural coasts with those of artificial plantations in botanical gardens in Taiwan as model for the effect of in situ and ex situ plant conservation on other organisms associated with this plant.

Materials and methods

Data collection

In this study, wild mature individuals of I. pes-caprae were collected from two sandy beach sites in the northern and central parts of Taiwan (Fig. 2). For comparing fungal endophytes between wild plants (“in situ”) and artificial plantation (“ex situ”), individuals of I. pes-caprae were collected from two botanical gardens in the northern and central parts of Taiwan. The distance between the two botanical gardens was about 130 km; for representing natural beach sites, two locations at the western coast between the two botanical gardens were chosen. Principally all detailed data were deposited in a dataset of Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://doi.org/10.15468/9h9rcg), where the standards of Darwin Cores and mycological practice were combined21. The strictly unified format of the Darwin Cores and the permanent deposit of data in GBIF enhance the accessibility and reusability of biodiversity data compared to the common practice of supplementary electronic materials in journals22. Furthermore, the dataset is much stricter reviewed and revised in a descriptive data paper than it is practicable for article supplements. Briefly, the major difference between the localities are the more inland locations of the botanical gardens compared to the coast and an average higher temperature in central Taiwan compared to northern Taiwan, whereas altitude was low in all collection sites. Plant samples were individually placed in plastic bags and returned to the laboratory and kept at 4 °C until further processing. Plants were processed for endophyte isolation within 48 h of sampling.

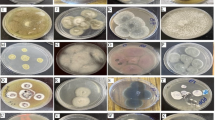

Altogether, 28 mature plants were collected, 9 each from natural coasts (Hsinchu and Taoyuan), and 5 each from the botanical gardens (Taichung and Taipei). Collections were done twice per year, namely in the winter and spring or summer, during the years 2013 to 2015 in the natural coasts and botanical gardens21. Because of limited availability of plants in the botanical gardens, additional collections were done in 2019 and 2020. Collections at additional localities at natural coasts in 2019 and 2020 as mentioned in Yeh & Kirschner (2023)21 were not considered here, because the number of strains was too low for significant analysis. Freshly collected plant samples were divided into different organs (roots, stems, and leaves) and then surface-sterilized21. The effectiveness was further controlled regularly by the imprint technique17. All isolates obtained from each plant sample were classified according to their morphological appearance into morphospecies. Representative isolates were investigated and deposited at the Bioresource and Collection Center, Hsinchu, Taiwan (BCRC). Dried cultures were deposited at the herbarium of the National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan (TNM). For molecular identification, total genomic DNA isolation, PCR, and sequencing of diverse barcode regions were performed as described by Yeh & Kirschner (2023)21. Depending on the sufficient resolution in the respective genus, sequences of the fatty acid elongase 1 gene, histone 3 gene, internal transcribed spacer of the rRNA genes (partial SSU rRNA gene, ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA gene, ITS2, partial LSU rRNA gene), large-subunit rRNA gene (LSU), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit genes, translation elongation factor 1-α gene, and β-tubulin gene were used21. DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank and the DNA Data Bank of Japan. Sequences were submitted to BLAST searches at GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). For BLAST searches, the parameters highlighted in Kirschner et al. (2023)23 were applied. Molecular data were cross-checked with micromorphology21. Depending on similarities in the barcodes and verifiability by morphology, strains were identified to species, genus, or higher taxonomic ranks. Only sequences cited in publications were considered for identification23,24. The scientific names retrieved from GenBank were updated with Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org).

Statistical data analysis

Based on the dataset described by Yeh & Kirschner (2023)21, isolation frequency was defined as the percent of tissue segments yielding an endophyte in culture. The relative abundance of fungal species was calculated using the following formula: RA = Ra/Rt ×100, where Ra: the total number of isolates of an endophyte taxon and Rt: the total number of isolates of all taxa. The colonization rate was defined as the percent of all fungal species in culture. The frequency of colonization (FC) of fungal species was calculated using the following formula: FC = Nc/Nt×100, where Nc was the total number of segments from which fungi were isolated in a sample, and Nt was the total number of segments used for isolation25. The diversity of endophytic fungi was evaluated by the most widely used indices of species diversity (Table 1), such as Simpson’s Index (D), Simpson’s Reciprocal Index (1/D) and Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H’) that were calculated to compare fungal assemblages between samples obtained in different sampling sites. Accumulation curves of fungal species in both botanical gardens (Fig. 3a) and two natural habitats (Taoyuan and Hsinchu) (Fig. 3b) were constructed, where the Y-axis indicates the number of species accumulation; and the X-axis indicates the number of plant collection events.

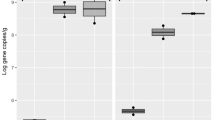

The dominant taxa (top 10 of RA) from each of the different sites (Table 2) were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA) by XLSTAT software (Version 2023.3.1 (1416), USA). For clear displaying, the results of PCA by XLSTAT software were repainted in R software (Version 4.0.2).

Results

The results indicate a great diversity and abundance of fungal endophytes associated with Ipomoea pes-caprae. From 2304 plants tissues from 28 plants, a total of 835 endophytic isolates belonging to over 100 morphospecies were isolated. These species belonged to the divisions Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota, corresponding to a total of 13 classes and 33 orders. Classes and orders included in the study are given in the previous description of the dataset deposited in GBIF21. The overall colonization rate of fungi in plants from botanical gardens (average 58.82%) was higher than in samples from natural habitats (average 35.07%). In terms of abundance, Aspergillus terreus, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Phyllosticta capitalensis were the dominant species in natural habitats, representing together 24.35% of the total isolates. Ph. capitalensis, Colletotrichum sp. 2, and Colletotrichum sp. 4 were dominant in artificial habitats, representing together 25.98% of the total isolates. Among these species, Ph. capitalensis was found in both habitats. Species richness and diversity indices of endophytic fungi in different habitats are shown in Table 1. It was also checked whether the ten most dominant species in each of the four sites also occurred at low (non-dominant) abundance in the other sites (Table 2). Several dominant species were only found in the artificial sites, but not natural coasts, e.g. in Colletotrichum. Some dominant species of Diaporthe were only isolated in botanical gardens, such as D. batatas and D. tulliensis, while other species of Diaporthe were exclusively found in the coastal sites. Neostagonospora spinificis was isolated from I. pes-caprae only in the coastal habitat. Overall, endophytic fungal community species richness and diversity were not significantly different between natural habitats and artificial habitats. The species accumulation curves show that the accumulation of species in the Taichung Botanical Garden was steeper compared to that from the Taipei Botanical Garden but both almost reached an asymptote after 4 sampling events (4 samples) (Fig. 3a). However, accumulation curves of the fungal species in natural sites (3 sampling events, 18 samples) did not reach an asymptote, indicating that there is a possibility of discovering more fungal species from natural sites if more sampling is done (Fig. 3b). The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the endophytic fungal species composition indicated a clear separation based on the sampling sites. Only the endophytic fungal species from the natural sites (Taoyuan and Hsinchu) clustered together. The first two axes of the PCA explained 62.78% of the total variation (Fig. 4).

Principal component analysis of the ten most dominant fungal endophytes isolated from different habitats of Ipomoea pes-caprae. Endophytic fungi are labeled as number and color correspond to different species (Table 2) and different sites (yellow: natural sites, green: Taichung Botanical Garden, blue: Taipei Botanical Garden, red: all sites), respectively. The PCA factors explain 62.78% of the total variance.

Discussion

As our analysis of the distribution of endophytes shows, plant-associated microbial communities within the same plant species depend on their habitats. The PCA demonstrates that there was a clear difference between the predominant fungi of the coastal sites and those of the artificial sites in botanical gardens. The compositions of fungal endophytes were also clearly different between the two botanical gardens. The environmental differences between the two botanical gardens were soil characteristics and temperature. According to the information from the gardeners, the soils where I. pes-caprae were planted in Taipei and Taichung botanical gardens were general soil and sea sand, respectively. The daily average temperature maxima in Taichung in central Taiwan are up to 3 °C higher than those in northern Taiwan (Taoyuan; https://weatherspark.com). The two botanical gardens are ex-situ plantations where the plants are grown for many years so that there was enough time for establishing associated endophytic microbiota. Environmental components, especially in soil composition may strongly influence the endophytic mycobiota. Our data suggest that the endophytic fungi from the coastal sites are replaced by local fungi in the artificial plantations.

Phyllosticta capitalensis was the single species that showed no obvious habitat trend, which may imply that this fungus is not specifically associated with the habitat. It may have a wider ecological amplitude than the other endophytic fungi and is not specific to I. pes-caprae, because Ph. capitalensis is one of the most widespread endophytic fungi in diverse plants26.

In contrast, Neostagonospora spinificis, recently described as endophyte and weak pathogen from the coastal grass Spinifex littoreus27, was found in the new host I. pes-caprae, which also indicates low specificity to the host, but high specificity to the sand coast habitat. Certain potentially plant pathogenic species of Colletotrichum, such as C. tropicale28, and Diaporthe, e.g. D. batatas, known as pathogen of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas29) and D. tulliensis on a broad range of hosts30, were found only in the botanical gardens. Other species of Diaporthe were found either in the botanical gardens or the sand coasts. The species of Aspergillus, Colletotrichum, Diaporthe and some other genera were distinguishable only by secondary barcodes in addition to the ITS barcode21. Their distinct distribution in different habitats highlights the importance of efforts towards species identification, since mere identification to the genus level would not resolve specific patterns of distribution. Relying only on ITS sequences leads to wrong designations of species names, such as “Aspergillus oryzae” for an endophytic fungus18. This species used in food production can be distinguished from the wild mycotoxigenic A. flavus only by the absence of mycotoxin production31.

In this study, we used a traditional culture-dependent approach for isolating endophytes which would only pick up the faster-growing species in general. The advantages were ex-situ preservation of the strains in a professional culture collection and the potential of applying diverse DNA barcodes for distinguishing species. Those species, however, which are difficult to cultivate or do not grow on artificial media are not detected with this method. Had analysis of DNA extracted directly from the plant been carried out with direct sequencing techniques such as metabarcoding, more species including those slow-growing and uncultivable ones, could theoretically have been discovered. However, some fungi are sometimes not detected with direct sequencing approaches using ITS primers; or the ITS barcodes do not allow resolution of species32. Fungal PCR may suffer from co-amplification of host plant DNA. Certain uncultivable fungi, such as arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi or latent pathogenic or endophytic Oomycota require specifically designed PCR procedures33,34.

Koch’s postulates are generally not applied in studies of endophytes. One reason may be a theoretical one, as the Koch’s postulates have been designed for symptomatic diseases, while endophytes are asymptomatic so that there are no symptoms which could be verified. Another reason is a practical one, since many plants subjected to endophyte study can hardly be grown under axenic conditions to the same mature stage as used in the field. An exception is Arabidopsis thaliana which has become a model plant because of its easy handling in the lab35. However, if the above-ground organs of the original plant species in infection experiments are replaced by roots of axenically grown A. thaliana, it would not be clear whether detecting endophytic fungi under such highly artificial settings mirrors the situation in nature or an experimental artifact.

Introduction of latent parasitic fungi by plants into botanical gardens is considered a danger11 or, in contrary, a chance of increased biodiversity36. In our study, however, the fungi in the botanical gardens were too different from those in the natural habitat so that potential pathogens may be rather acquired from the new environment than introduced from the original habitat. In our observation of I. pes-caprae in the natural habitats and botanical gardens, except for Cercospora leaf spots (data not shown), no disease symptoms were found. Among the diseases associated with 15 species of plant pathogenic fungi recorded from I. pes-caprae, only leaf spot associated with Cercospora species has been recorded from this host in more than ten countries (US Department of Agriculture Fungal Databases https://fungi.ars.usda.gov/, accessed 24. Dec. 2024). Therefore, the dominant endophytes were probably predominantly saprobic decomposers of leaves as well as potential mutualists. However, clarifying the roles of these fungi and interactions with the plant requires experimental study.

Nowadays, there are ca. 2500 botanic gardens in the world, but there are only some 480 registered microbial collection centres14,37. The ratio is similar in Taiwan with several major botanical gardens (about ten), but only one professional culture collection (Bioresource Collection & Research Center, BCRC). Representative strains of most species in our study were deposited in BCRC21. This deposit serves as source for further taxonomic and applied research as well as ex situ conservation. As it has been shown for orchid mycorrhiza fungi, preserved living strains can be used for restauration of orchid populations38. Due to the limited capacities of culture collections, only randomly selected strains could be preserved. Numerous fungi which are important for ecology cannot be cultured and the conservation of fungi is definitely inadequate and usually focused on ex situ preservation14. Due to our finding of habitat-driven occurrence of endophytes and to the limitations of ex situ conservation of plant-associated fungi, in situ conservation should be much higher valued than in the present concepts of nature conservation. Ex situ plant conservation is limited to the conservation of single species but is without benefit to the associated microbiota.

Data availability

The dataset upon which the study was based was deposited in the repository of Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), https://doi.org/10.15468/9h9rcg. The dataset was described without analysis in the format of a data paper in Yeh Y-H, Kirschner R (2023) The diversity of cultivable endophytic fungi of the sand coast plant Ipomoea pes-caprae in Taiwan. Biodiversity Data Journal 11:e98878. The dataset includes specimen and strain numbers, geodetic data, and links to GenBank accession numbers and fungal names in Index Fungorum.

References

Maun, M. A. The Biology of Coastal Dunes (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Maximiliano-Cordova, C. et al. Does the functional richness of plants reduce wave erosion on embryo coastal dunes? Estuaries Coasts 42, 1730–1741 (2019).

Chen, T. H., Yu, H. M. & Horng, F. W. The movement of shifting sand and the growth of sand stabilizing plants at Shitsugan Coast, Taoyuan. Q. J. Chin. For. 37 (4), 367–377 (2004). (In Chinese).

Wilson, D. Endophyte: The evolution of a term, and clarification of its use and definition. Oikos 73, 274–276 (1995).

Hawksworth, D. L. & Lücking, R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol. Spectr. 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0052-2016 (2017). FUNK-0052–2016.

Stierle, A., Strobel, G. & Stierle, D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science 260, 214–216 (1993).

Sasaki, T. et al. A new anthelmintic cyclodepsipeptide, PF1022A. J. Antibiot. 45(5), 692–697. https://doi.org/10.7164/antibiotics.45.692 (1992).

Stadler, M. & Kolarik, M. Taxol is NOT produced sustainably by endophytic fungi ! – a case study for the damage that scientific papermills can cause for the scientific communities. Fungal Biol. Rev. 49, 100367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2024.100367 (2024).

Jia, M. & Qin, L. P. A friendly relationship between endophytic fungi and medicinal plants: A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 7, 906. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00906 (2016).

Kirschner, R. Fungi on the leaf- a contribution towards a review of phyllosphere microbiology from the mycological perspective. In Biodiversity and Ecology of Fungi, Lichens, and Mosses (ed Blanz, P.) 433–448 (Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2018).

Hayden, K. Botanic gardens and plant pathogens: A risk-based approach at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Sibbaldia 18, 127–139. https://doi.org/10.24823/Sibbaldia.2020.293 (2020).

McGowan, P. J. K., Traylor-Holzer, K. & Leus, K. IUCN guidelines for determining when and how ex situ management should be used in species conservation. Conserv. Lett. 10, 361–366 (2017).

Vander Mijnsbrugge, K., Bischoff, A. & Smith, B. A question of origin: Where and how to collect seed for ecological restoration. Basic. Appl. Ecol. 11, 300–311 (2010).

Gams, W. Ex situ conservation of microbial diversity. In Microorganisms in Plant Conservation and Biodiversity (eds Sivasithamparam, K., Dixon, K. W. & Barrett, R. L.) 269–283 (Kluwer Academic, 2002).

Hawksworth, D. L. Fungal diversity and its implications for genetic resource collections. Stud. Mycol. 50, 9–18 (2004).

Redman, R. S., Sheehan, K. B., Stout, R. G., Rodriguez, R. J. & Henson, J. M. Thermotolerance conferred to plant host and fungal endophyte during mutualistic symbiosis. Science 298, 1581 (2002).

Rodriguez, R. J. et al. Stress tolerance in plants via habitat-adapted symbiosis. ISME J. 2, 404–416 (2008).

Rashad, Y. M., Tami, A. & Abdalla, M. S. Eliciting transcriptomic and antioxidant defensive responses against Rhizoctonia root rot of sorghum using the endophyte Aspergillus oryzae YRA3. Sci. Rep. 13, 19823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46696-7 (2023).

Sánchez-Márquez, S., Bills, G. F., Domínguez Acuña, L. & Zabalgogeazcoa, I. Endophytic mycobiota of leaves and roots of the grass Holcus lanatus. Fungal Divers 41, 115–123 (2010).

Mendoza-González, G., Martínez, M. L. & Lithgow, D. Biological flora of coastal dunes and wetlands: Canavalia rosea (Sw.) DC. J. Coast Res. 30, 697–713. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-13-00106.1 (2014).

Yeh, Y. H. & Kirschner, R. The diversity of cultivable endophytic fungi of the sand coast plant Ipomoea pes-caprae in Taiwan. Biodivers. Data J. 11, e98878. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.11.e98878 (2023).

Osawa, T. Perspectives on biodiversity informatics for ecology. Ecol. Res. 34, 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1703.12023 (2019).

Kirschner, R., Lin, L. D. & Yeh, Y. H. Using BLAST in molecular species identification of fungi 1: Practical guidelines. Nova Hedwig 116 (1–2), 67–76 (2023).

Yeh, Y. H., Lin, L. D. & Kirschner, R. Using BLAST in molecular species identification of fungi 2: Gliomastix roseogrisea (Ascomycota, Hypocreales) as example for in-depth identification check. Nova Hedwig 116 (1–2), 137–153 (2023).

Hammami, H. et al. Impact of a natural soil salinity gradient on fungal endophytes in wild barley (Hordeum maritimum With.). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2142-0 (2016).

Wikee, S. et al. Phylogenetic re-evaluation of Phyllosticta (Botryosphaeriales). Stud. Mycol. 76 (1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3114/sim0019 (2013).

Yang, J. W., Yeh, Y. H. & Kirschner, R. A new endophytic species of Neostagonospora (Pleosporales) from the coastal grass Spinifex littoreus in Taiwan. Botany 94, 593–598 (2016).

De-Silva, D. D. et al. Identification, prevalence and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of Capsicum annuum in Asia. IMA Fungus 10, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-019-0001-y (2019).

Wu, C. et al. Study of sweet potato storage disease and etiology. J. Taiwan. Agric. Res. 68, 28–39 (2019).

Serrato-Diaz, L. M., Aviles-Noriega, A., Rivera-Vargas, L. I. & Goenaga, R. First report of Diaporthe tulliensis causing necrotic spots and leaf blight on rambutan in Puerto Rico. Plant. Dis. 107, 3640. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-22-2058-PDN (2023).

Frisvad, J. C. et al. Taxonomy of Aspergillus section Flavi and their production of aflatoxins, ochratoxins and other mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 93, 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2018.06.001 (2019).

Dissanayake, A. J. et al. Direct comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent molecular approaches reveal the diversity of fungal endophytic communities in stems of grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Fungal Divers. 90, 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-018-0399-3 (2018).

Kohout, P. et al. Comparison of commonly used primer sets for evaluating arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities: Is there a universal solution? Soil. Biol. Biochem. 68, 482–493 (2014).

Ploch, S. & Thines, M. Obligate biotrophic pathogens of the genus Albugo are widespread as asymptomatic endophytes in natural populations of Brassicaceae. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3692–3699 (2011).

Keim, J., Mishra, B., Sharma, R., Ploch, S. & Thines, M. Root-associated fungi of Arabidopsis thaliana and Microthlaspi perfoliatum. Fungal Divers. 66, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-014-0289-2 (2014).

Lotz-Winter, H. et al. Fungi in the Botanical Garden of the University of Frankfurt am Main. Z. Mykol 77, 89–122 (2011). (in German).

Golding, J. et al. Species-richness patterns of the living collections of the world’s botanic gardens: A matter of socio-economics? Ann. Bot. 105, 689–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq043 (2010).

Těšitelová, T., Klimešová, L., Vogt-Schilb, H., Kotilínek, M. & Jersáková, J. Addition of fungal inoculum increases germination of orchid seeds in restored grasslands. Basic. Appl. Ecol. 63, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2022.04.001 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank two former lab member Liang-Ting Lu and Wen-Chen Huang for technical assistance. The study was supported by the Ministry of Science & Technology of Taiwan (MOST 108-2621-B-002-007, 109-2621-B-002-004, 110-2621-B-002-001-MY2, NSTC 110-2811-B-002-568, NSTC 111-2811-B-002-092, NSTC 112-2811-B-002-150). The technical foundations for this study were laid by annual workshops about GBIF/TaiBIF since 2016 supported by MOST and organised by the Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei. The permits for collection in the botanical gardens of Taipei City and National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science & Technology of Taiwan (MOST 108-2621-B-002-007, 109-2621-B-002-004, 110-2621-B-002-001-MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yu-Hung Yeh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yu-Hung Yeh and revised in depth by Roland Kirschner. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Research involving plants

Collection of materials complied with national and international legislation, because I. pes-caprae is a common, pantropically distributed plant whose populations in Taiwan are neither endangered nor protected and because there was no trading of the plant. We acknowledge the permission of collecting I. pes-caprae in the two botanical gardens in Taiwan, where living vouchers are cultivated, as indicated above. Details of deposit of voucher specimens as identified by both authors, strains, and DNA barcode sequences were given in our cited data paper (see “Data Availability”) following the instructions of the data paper format and regulations of GBIF being much more standardized and stricter than required for other types of publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeh, YH., Kirschner, R. Study of endophytic fungi of Ipomoea pes-caprae reveals the superiority of in situ plant conservation over ex situ conservation from a mycological view. Sci Rep 15, 2040 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86508-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86508-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Identity and diversity of culturable endophytic fungi associated with Capparis spinosa L. in Iran

Scientific Reports (2025)