Abstract

With the aim of improving access and engagement to healthcare in people living with HIV (PLHIV), in 2022 Gregorio Marañón Hospital and the NGO COGAM developed a circuit for recruitment and referral to hospital. Program targeted PLHIV who were neither receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) nor on medical follow-up (FU); but also, individuals at risk who underwent screening tests at the NGO and, if positive, were referred for confirmation. The result was an increase in annual new PLHIV seen in hospital by reaching a population who were, essentially, young men (94% male, median age 30 years), migrants (95%) with recent diagnosis of HIV (median 5 years) and who were recently arrived in Spain (median 5 months). Most of them hadn´t healthcare coverage (78%). In multivariate analysis, that included all PLHIV seen for the first time in the ID Unit between 2019 and 2022, lack of healthcare coverage was the only independent predictor of lost to FU that reached statistical significance (HR 5.19, CI 2.76–9.47). Furthermore, time from HIV diagnosis to ART initiating was shortened from 14 to 6 days without affecting linkage to care. Our conclusion is that collaboration with NGOs reinforce diagnosis, FU, and adherence to ART for PLHIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV treatment regimens have progressively gained in effectiveness and tolerability over the decades. Therefore, nowadays and worldwide, virological failure normally isn’t due to inefficacy of antiretroviral treatment regimen but rather to lack of continuous supply of medication or poor therapeutic adherence. It has been demonstrated that undetectable viral load in people living with HIV (PLHIV) suppress viral transmission1,2; and moreover, it radically reduces mortality, both for HIV related diseases but also for non-HIV related conditions3. UNAIDS has set global targets to be achieved by 2030: 95% of HIV-infected patients will be diagnosed; 95% of those diagnosed will be on antiretroviral treatment; 95% of them will reach undetectable HIV viral load (95–95-95)4,5. Achieving these goals will depend, therefore, not on the emergence of new antiretroviral drugs or new treatment regimens, but on the access to HIV medication and linkage to healthcare.

In Madrid, which has a public universal healthcare system; coverage on public health diseases, including HIV infection, is mandatory. Therefore, medical care and treatment for those diseases are entirely free6. The city also has a wide network of hospitals and clinics. However, factors such as healthcare system saturation, immigration, social exclusion, and stigma have been identified as barriers to accessing healthcare centers for PLHIV and individuals at risk of infection7. In 2022, Infectious Diseases (ID) Unit in Gregorio Marañón University Hospital (HGUGM) and non-governmental organization (NGO) COGAM developed a project entirely implemented in the community, meaning outside the hospital environment; aimed at the recruitment and direct referral to the hospital with the objective to reinforce linkage to care in PLHIV. Here we present the results obtained and the impact of this project on the activity of the HIV Ward compared to previous years.

Materials and methods

The HGUGM is a tertiary hospital that is part of the public hospital network in Madrid. Users can access either from the Emergency Ward, or from Primary Care, or from referral from other public healthcare centers.

COGAM, on the other hand, is a non-profit NGO focused on serving the LGBT+ community in Madrid. At its headquarters, they carry out rapid diagnosis tests for HIV and HCV infection anonymously and free of charge. COGAM workers also have mobile units that reach and recruit population at risk for infection in hot spots as migrant centers and associations. They have also a great activity in social media which reinforce their links with this population.

In 2022, with the aim of facilitating and reinforcing access to the healthcare system for PLHIV and population at risk; both institutions, HGUGM and COGAM, carried out an informative, divulgate HIV-project but also screening, recruitment, and referral-to-care program whose geographical spot of intervention was extrahospitallary, thus took place in the community. For this purpose, usual activity of COGAM was increased through informative sessions at its headquarters open to the public; intensification of their activity on social networks; and increasing the number of kits available for rapid diagnosis. At the same time, a circuit for direct and rapid referral to the ID Unit of the HGUGM was established.

To analyze the results of this intervention in PLHIV and also the impact it had on the ID Unit, a retrospective observational study was conducted of all people with HIV infection who had initiated follow-up and treatment for their infection at the HGUGM between 1st January 2019 to 31st December 2022. We selected this time period to include both the intervention time and the previous period showing ID Unit usual activity, which we extended to reach the pre-pandemic year, to avoid the potential effect COVID could have had on the study population. We included patients newly diagnosed who had not yet received ART and patients with previous diagnose of HIV infection performed in other centers who attended the HGUGM for continuity of care.

For all of them and through the information provided in the hospital’s electronic medical records, epidemiological, social, clinical, and immunovirological variables were collected. After performing descriptive analysis, we compared the characteristics of those patients referred from NGOs with those patients who came through conventional referral channels that are entirely from and within the healthcare system.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Istanbul and was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, which waived informed consent for the collection of clinical data (Code: MICRO.HGUGM.2022-026). All the processes satisfied the local data confidentiality requirements.

Statistical analysis

The results of continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range (percentile 25; percentile 75). For categorical variables, results are shown in frequencies and percentages. Normality analysis was studied from frequency histograms and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

To study the differences in means between the two groups, parametric tests (Student’s t-test or ANOVA) or non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis) were used, choosing the most appropriate one in each case based on the normality of the data and the total number of patients in each group. The association between qualitative variables was studied using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

To study the predictive factors of loss to follow-up, Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression were utilized. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Bilateral tests were employed, and results with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Between1st January 2019 to 31st December 2022, the ID Unit of HGUGM received 500 new patients diagnosed with HIV infection. Among these, 203 were newly diagnosed cases (53 in 2019, 38 in 2020, 49 in 2021, 60 in 2022) and 297 were patients referred from other healthcare centers to HGUGM for continuity of HIV care and treatment (62 in 2019, 45 in 2020, 53 in 2021, 135 in 2022). 86 of all these patients were referred from an NGO, of which 21 were newly diagnosed with HIV infection and 67 were patients with previously known infection. In 2019, no patients were referred from an NGO, in 2020 only one for continuity of care for a known HIV infection, and in 2021 seven patients, three of whom were newly diagnosed with the infection. In 2022, following the direct referral program established with COGAM, the number increased to 78 patients with HIV infection referred from NGOs: 17 were naive cases and the rest were previously diagnosed patients.

Of the total 500 patients, their epidemiological, clinical and social characteristics are shown in Table 1.

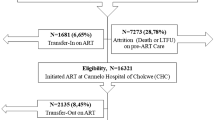

At the end of the study, there were 43 (9%) patients who were lost to follow-up (LFU) from the total included, of which 14 (16%) came from NGOs. 82% (401) of the overall patients in the study maintained active follow-up at the end of the study period; and 75% (66) of those coming from NGOs. When analyzing other causes to discontinue follow-up in our clinic apart from LFU, such as transfer to another hospital, move to other Community in Spain, or return to country of origin, no differences were found between patients from the NGO compared to those who had accessed our ID service through other means. A multivariate analysis of factors associated with LFU was conducted using Cox regression and adjusting for country of origin other than Spain; NGO origin; time in Spain (less than 1 year, between 1 and 10 years, and more than 10 years); IV drug user risk group, CDC stage C; and health coverage at the end of the study. Only the absence of health coverage at the time of study closure reached statistical significance as an independent factor for LFU (HR 5.19, CI 2.76–9.47). Other factors such as coming from an NGO (HR 1.94, CI 0.99–3.89) or being from a country other than Spain (HR 3.08, CI 0.93–10.16) nearly reached significance. It is important to note that the number of losses in the overall study is small, which limits this analysis (Fig. 1).

For naive patients, establishing a direct referral pathway to the hospital from the NGO helped shorten the time from HIV diagnosis to the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART): 6 days for naive patients from an NGO, compared to 14 days for other newly diagnosed individuals (p = 0.054). Hence, we aimed to analyze whether early initiation of ART was associated with a higher LFU. For this, a multivariate analysis using Cox regression for LFU in the naive patients of our study was conducted, adjusted for: delay in the start of ART (less than 7 days, between 7 and 14 days, and more than 14 days); country of origin other than Spain; NGO origin; time in Spain (less than 1 year, between 1 and 10 years, and more than 10 years); CDC stage C; and health coverage at the end of the study. None of these factors showed statistical significance as predictors of loss to follow-up, although the number of losses to follow-up was very small, limiting the power of the analysis (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The project presented demonstrates that the collaboration of health institutions with NGOs in conducting community interventions is an essential strategy for linking PLHIV to the healthcare system. In the epidemiological control of HIV infection, the challenge is to provide access to ART for every infected patient. Globally, obtaining these drugs requires visiting healthcare institutions, typically hospitals, where the medication is dispensed. In this process, PLHIV may encounter multiple barriers that ultimately impede achieving the UNAIDS targets for 2030 “95-95-95”. These barriers vary by individual according to his geographic area of residence and the healthcare setting he is in; but globally the main issues are stigma and difficulty accessing healthcare facilities to obtain medication7,8,9,10. These two aspects also have an impact on the psychological sphere, worsening the negative health and wellbeing effects of the infection11.

Regarding stigma, often stigma inherent to HIV infection overlaps with that linked to certain groups such as men who have sex with men, transgender people, non-Caucasian races, or migrants12,13,14,15. Concerning accessibility to healthcare, while ART is available worldwide, there are obstacles such as the physical distance from a patient’s residence to healthcare centers; or the lack of health coverage that prevents the admission on healthcare system. Addressing all these issues is where healthcare institutions have many limitations, and where direct collaboration with NGOs can be of great help.

In public health, for the prevention in transmission of infections that are a threat to the community, collaboration between governments and NGOs has led to improvements in epidemiological control16,17,18,19. Regarding HIV, NGOs have always played a crucial role in preventing infection and in accessing treatment for infected individuals, serving as a link with socially excluded groups such as sex workers, drug addicts, migrants, or the homosexual population20,21.

Concerning PLHIV and individuals at risk of infection, in countries where stigma towards the community of men who have sex with men has been identified as the main obstacle to accessing HIV diagnosis, such as China22, India23, or Cameroon24,25, community strategies have been implemented to facilitate access to the healthcare system and antiretroviral medication.

In Western countries where health standards and legislation should be favorable to ensuring therapeutic coverage for PLHIV, there are still infected individuals who do not undergo treatment. The migrant population is particularly vulnerable26, representing over 50% of new HIV infection diagnoses in Spain27, most of them late presenters28. Therefore, screening and counseling strategies are necessary in this population29. Despite optimizing resources from institutions, it is imperative to intervene directly in the community so collaboration with NGOs is essential. In Catalonia (Spain), there is already close collaboration with HIV-related NGOs, and currently, 30% of new HIV infection diagnoses in this region are made in these organizations30,31.

Our work is conducted in Madrid, where coverage for patients with public health diseases, including HIV infection, is universal and free. However, the program presented in this work, involving direct collaboration with NGOs for community intervention, has allowed us to reach a population that does not enter healthcare system through conventional channels, and to whom we were not previously providing coverage, posing a threat to the epidemiological control of HIV pandemic. In our analysis, we found distinctive characteristics of these individuals compared to the rest of PLHIV. They were, essentially, men or transgender women infected by sexual transmission, predominantly newly arrived migrants to Spain in irregular administrative situation. Almost all came from Latin American countries. Overall, no differences were observed in terms of HIV clinical manifestations, immunovirological status, or presence of other comorbidities.

We analyzed sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that were registered in clinical records by the time patients were first seen in the hospital and also throughout the follow-up in our center. We emphasize that the main objective of this study was not the analysis of STIs and that the direct collaboration project with the NGO focused on HIV infection, without any specific diagnostic or therapeutic strategy for STIs. Therefore, we believe that the STIs incidence found in our study may be underestimated. Despite this, that incidence was remarkable in both groups as 17% of PLHIV from the total individuals included in the study presented some type of STI during follow-up in our center.

Simultaneously, the establishment of a direct referral pathway has allowed prompt evaluation of these HIV patients in the hospital, streamlining the initiation of ART in naive patients. Strategies for rapid initiation of ART have been questioned for their potential limitations in promoting linkage to healthcare system for PLHIV, particularly for vulnerable populations32,33,34. However, some studies conducted in low-income countries seem to indicate the opposite35, as well as publications in vulnerable populations in the United States36,37. In our work, in naive patients, we did not find differences in the risk of LFU in those who initiated ART in the first 7 days compared to those initiated in the first 14 days or later, although a limitation of our analysis is that the number of losses was very low. On the other hand, our community interventional program for diagnosis and referral to healthcare in PLHIV did not find a favorable impact on early diagnosis of HIV infection, as the median CD4 count at diagnosis in naïve patients was similar in both groups, derived and not derived from NGOs, although that median was above 350 cells/microliter.

In the presented collaboration project between HGUGM and the NGO COGAM for the direct referral of PLHIV to the hospital, social workers from both institutions were integrated. They provided counseling and administrative assistance to migrant population, thereby achieving integration into the healthcare system for most of the included patients. Thus, while patients from NGOs compared to those accessing the healthcare system through other channels were significatively higher on administrative exclusion at the start and at the end of the study, the proportion of patients from NGOs in social exclusion decreased from 78% upon arrival at the hospital to 26% at the end of the study due to the work of the social workers. This had a very favorable impact on treatment adherence and linkage to care, as reflected in administrative exclusion being the only factor related to LFU in our analysis. The legal absence of healthcare coverage had already been identified in previous studies as the main barrier to access to ART in Europe38,39,40.

Conclusions

Direct collaboration with NGOs to reinforce the diagnosis, medical follow-up, and treatment adherence of people living with HIV infection allows for direct intervention in the community, accessing a group of patients who do not use standardized referral channels. These PLHIV are primarily migrant homosexual men from South American countries, newly arrived in Spain and still in administrative exclusion. Despite the availability of ART in Spain, this situation of administrative exclusion is the main barrier to accessing the healthcare system and the main factor associated with loss to follow-up in PLHIV. Collaboration with NGOs within a multidisciplinary team including doctors, nurses, and social workers facilitates the administrative incorporation into healthcare systems of individuals in exclusion. Furthermore, establishing a direct referral pathway to Infectious Diseases Services in newly diagnosed naive HIV patients shortens the time to initiate ART without impacting treatment adherence or retention in the healthcare system.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral treatment

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- PLHIV:

-

People living with HIV

- LGBT+:

-

Lesbian, gays, bisexual, transgender

- ID:

-

Infectious diseases

- HGUGM:

-

Gregorio Marañón University Hospital

References

Cohen, M. S. et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(9), 830–839 (2016).

Rodger, A. J. et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 393(10189), 2428–2438 (2019).

Lundgren, J. D. et al. Long-term benefits from early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV infection. NEJM Evid. https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2200302 (2023).

https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_en.pdf. Last accessed on 19 May 2024.

Frescura, L. et al. Achieving the 95 95 95 targets for all: A pathway to ending AIDS. PLoS ONE 17(8), e0272405 (2022).

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Boletín Oficial del Estado—Legislación Consolidada, 2012. Available at http://www.msssi.gob.es/profesionales/ prestacionesSanitarias/CarteraDeServicios/docs/RDL_16_2012.pdf. Last accessed 19 May 2024.

Ndumbi, P. et al. Barriers to health care services for migrants living with HIV in Spain. Eur. J. Public Health 28(3), 451–457 (2018).

Latkin, C., Weeks, M. R., Glasman, L., Galletly, C. & Albarracin, D. A dynamic social systems model for considering structural factors in HIV prevention and detection. AIDS Behav. 14(Suppl 2), 222–238 (2010).

Auerbach, J. D., Parkhurst, J. O. & Cáceres, C. F. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob. Public Health 6(Suppl 3), S293-309 (2011).

Arora, A. K. et al. Barriers and facilitators affecting the HIV care cascade for migrant people living with HIV in organization for economic co-operation and development countries: A systematic mixed studies review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 35(8), 288–307 (2021).

Qiao, S., Li, X. & Stanton, B. Social support and HIV-related risk behaviors: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS Behav. 18(2), 419–441 (2014).

Flowers, P. et al. Diagnosis and stigma and identity amongst HIV positive Black Africans living in the UK. Psychol. Health 21, 109–122 (2006).

Boyd, A. E. et al. Ethnic differences in stage of presentation of adults newly diagnosed with HIV-1 infection in south London. HIV Med. 6, 59–65 (2005).

Scheppers, E. et al. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: A review. Family Practice 23, 325–348 (2006).

Deblonde, J. et al. Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. Eur. J. Pub. Health 20, 422–432 (2010).

Sanadgol, A., Doshmangir, L., Majdzadeh, R. & Gordeev, V. S. Engagement of non-governmental organisations in moving towards universal health coverage: A scoping review. Global Health 17(1), 129 (2021).

Rajabi, M., Ebrahimi, P. & Aryankhesal, A. Collaboration between the government and nongovernmental organizations in providing health-care services: A systematic review of challenges. J. Educ. Health Promot. 30(10), 242 (2021).

Zafar Ullah, A. N., Newell, J. N., Ahmed, J. U., Hyder, M. K. & Islam, A. Government-NGO collaboration: The case of tuberculosis control in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 21(2), 143–155 (2006).

Rangan, S. G. et al. Tuberculosis control in rural India: Lessons from public-private collaboration. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 8(5), 552–559 (2004).

Kelly, J. A. et al. Programmes, resources, and needs of HIV-prevention nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Africa, Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. AIDS Care 18, 12–21 (2006).

Sehgal, P. N. Prevention and control of AIDS: The role of NGOs. Health Millions 17, 31–33 (1991).

Chow, E. P. et al. HIV prevalence trends, risky behaviours, and governmental and community responses to the epidemic among men who have sex with men in China. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 607261 (2014).

Bhutada, K. et al. Pathways between intersectional stigma and HIV treatment engagement among men who have sex with men (MSM) in India. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 22, 23259582231199400 (2023).

Holland, C. E. et al. Access to HIV services at non-governmental and community-based organizations among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Cameroon: An integrated biological and behavioral surveillance analysis. PLoS One 10(4), e0122881 (2015).

Park, J. N. et al. Correlates of prior HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Cameroon: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 25(14), 1220 (2014).

Deblonde, J. et al. Restricted access to antiretroviral treatment for undocumented migrants: a bottle neck to control the HIV epidemic in the EU/EEA. BMC Public Health 15, 1228 (2015).

Área de Vigilancia de VIH y Comportamientos de Riesgo. Vigilancia Epidemiológica del VIH y sida en España: Sistema de Información sobre Nuevos Diagnósticos de VIH y Registro Nacional de Casos de Sida. Plan Nacional Sobre el SIDA, 2016. Available at http://www.mscbs.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/vigilancia/docs/Informe_VIH_SIDA_2023.pdf.

Monge, S. et al. Inequalities in HIV disease management and progression in migrants from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain. HIV Med. 14(5), 273–283 (2013).

Alvarez-del Arco, D. et al. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pub. Health 23, 1039–1045 (2013).

Berenguera, A. et al. Core indicators evaluation of effectiveness of HIV-AIDS preventive-control programmes carried out by nongovernmental organizations. A mixed method study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 176 (2011).

Carta al director: Berenguera, A., Almeda, J., Violan, C., Pujol-Ribera, E. Percepción del riesgo de infección por VIH-SIDA de los usuarios de las organizaciones no gubernamentales que trabajan en la prevención-control del VIH-SIDA en Catalunya [Perception of the risk of HIV-AIDS infection of users by Non-Governmental Organisations (ONGs) who work in prevention-control of HIV-AIDS in Catalonia]. Aten Primaria. 44(5), 293–295 (2012) (Spanish).

Ford, N. et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 32(1), 17–23 (2018).

Cuzin, L. et al. Too fast to stay on track? Shorter time to first anti-retroviral regimen is not associated with better retention in care in the French Dat’AIDS cohort. PLoS One 14(9), e0222067 (2019).

Mbatia, R. J. et al. Interruptions in treatment among adults on anti-retroviral therapy before and after test-and-treat policy in Tanzania. PLoS One 18(11), e0292740 (2023).

Koenig, S. P. et al. Same-day HIV testing with initiation of antiretroviral therapy versus standard care for persons living with HIV: A randomized unblinded trial. PLoS Med. 14(7), e1002357 (2017).

Coffey, S. et al. RAPID antiretroviral therapy: High virologic suppression rates with immediate antiretroviral therapy initiation in a vulnerable urban clinic population. AIDS 33(5), 825–832 (2019).

Colasanti, J. et al. Implementation of a rapid entry program decreases time to viral suppression among vulnerable persons living with HIV in the Southern United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 5(6), ofy104 (2018).

Suess, A., Ruiz Perez, I., Ruiz Azarola, A. & March Cerda, J. C. The right of access to health care for undocumented migrants: A revision of comparative analysis in the European context. Eur. J. Public Health 24, 712–720 (2014).

Vignier, N. et al. Refusal to provide healthcare to sub-Saharan migrants in France: A comparison according to their HIV and HBV status. Eur. J. Public Health 28(5), 904–910 (2018).

Nöstlinger, C. et al. HIV among migrants in precarious circumstances in the EU and European economic area. Lancet HIV 9(6), e428–e437 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Gilead Grants, project number:14855

Funding

This project received grant from Gilead Grants (project number:14855).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Teresa Aldamiz-Echevarria (TAE), Chiara Fanciulli (CF), Mónica López (ML), Leire Pérez (LP), Francisco Tejerina (FT), David Sánchez (DS), Blanca Lodeiro (BL), Juan Carlos López (JCL), Juan Brerenguer (JB), Cristina Diez (CD) contributed to the study development, data collection, data analysis and redaction of the manuscript Jose Maria Bellón (JMB) contributed in the statistical analysis Maria Ferris (MF), Mario Blazquez (MB), Almudena Calvo (AC), Mario Domene (MD), Oswaldo Vegas (OV), Carmen Rodriguez (CR) contributed to the study development Patricia Muñoz (PM), Paloma Gijón (PG), Pedro Montilla (PM), Elena Bermúdez (EB), Maricela Valerio (MV), Roberto Alonso (RA), Belen Padrilla (BP), Cristina Ventimilla (CV) contributed to the study development and redaction of the manuscript All authors agree for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital (Code: MICRO.HGUGM.2022-026).

Consent for publication

All authors agree for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldámiz-Echevarria, T., Fanciulli, C., Lopez, M. et al. Direct collaboration between hospitals and NGOs, an essential tool to reinforce linkage to care in people living with HIV. Sci Rep 15, 3583 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86540-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86540-8