Abstract

As global demand for fossil fuels rises amidst depleting reserves and environmental concerns, exploring sustainable and renewable energy sources has become imperative. This study investigated the pyrolysis of corncob, a widely available agricultural waste, using urea as a catalyst to enhance bio-oil production. The aim was to determine the optimum urea concentration and pyrolysis temperature for bio-oil yield from corncob. A series of experiments were conducted at varying temperatures (350 °C, 400 °C, and 450 °C) and urea concentrations (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) to assess their impact on bio-oil yield, chemical composition, and energy content. Fourier Transform-Infrared Spectroscopy, Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS), Ultimate Analysis, and High Heating Value (HHV) analyses were employed to evaluate the quality of bio-oil produced. Results indicate that a 10% urea concentration at 400 °C improves bio-oil yield from 49.33 to 54.66%. FT-IR analysis revealed enhanced absorption in key functional group regions, including O–H, N–H, C–H, C=O, and C–O, for bio-oil treated with 10% urea compared to untreated bio-oil. Ultimate analysis indicates that urea treatment improved bio-oil quality by increasing carbon (84.80–86.40%), nitrogen (2.29–2.68%), and oxygen (7.22–8.31%) contents while reducing hydrogen (5.09–2.38%) and sulfur (0.62–0.20%) contents, with improvement in the HHV from 36.12 to 37.12 MJ/kg. GC–MS analysis further revealed the presence of nitrogenous compounds, notably siloxanes in the bio-oil produced with urea infusion. This research highlights the potential of urea-catalyzed pyrolysis as a viable method for converting corncob into high-energy bio-oil, offering a promising alternative to traditional fossil fuels while addressing sustainability and environmental impact challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given the increasing global demand for fossil fuels, depleting crude oil reserves, and heightened environmental concerns, the development of sustainable and renewable energy sources has become crucial. Biomass waste, composed primarily of lignocellulosic materials derived from plants and animals, presents a promising alternative due to its abundance and renewability1. Annually, plant-based lignocellulosic biomass amounts to approximately 181 billion tonnes, though only 3.5% of this vast resource is currently utilized for energy production2. The conversion of biomass to energy offers not only an alternative fuel source but also an efficient method of waste valorisation2. Among the various biomass sources, corncob has shown significant potential for bio-oil production, positioning itself as a promising alternative to conventional fossil fuels3. This potential is further enhanced by the fact that corncobs are often discarded as waste, making them an underutilized resource.

Corncob, a substantial by-product of corn cultivation, constitutes approximately 75–85% of the total weight of corn ears following grain removal4. Like other lignocellulosic biomass, the cell wall of corncob is primarily composed of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, with cellulose being the dominant component5. Corn is one of the most widely cultivated crops globally, contributing an annual global biomass production of approximately 1.2 billion tonnes6, with 11 million tonnes produced annually in Nigeria alone7. This vast production volume highlights the potential of corncob as a renewable resource for biofuel production and other industrial applications.

Several methods are available for converting biomass, such as corncob, into usable energy, including chemical, biochemical, mechanical, and thermochemical approaches. Among these, thermochemical conversion has garnered significant attention due to its applicability in biomass utilization1. Pyrolysis is a standard thermochemical method that has shown considerable promise in industrial applications. The process parameters of pyrolysis can be optimized to maximize the yield of valuable products, making it a particularly effective approach for the conversion of biomass8. The pyrolysis of corncob has already been explored with notable success, offering significant prospects for bio-oil production and other energy applications.

Singh and Sawarkar9 conducted an in-depth study on the pyrolysis of corncob, detailing its physio-chemical properties, thermal degradation characteristics, and kinetic behavior. Their analysis revealed that corncob, with a high cellulose and hemicellulose content (76.23%), holds significant potential for bio-oil production, with the greatest mass loss occurring between 180 and 360 °C. Similarly, Janewit et al.10 conducted a comparative study on the fast pyrolysis of rice husk, rice straw, and corncob, observing that corncob exhibited the highest weight loss rate, attributed to its low lignin and high cellulose content. In contrast, rice husk, which contains higher lignin levels, demonstrated the slowest pyrolysis rate. These results indicate that corncob is more efficient for pyrolysis than rice husk and rice straw.

The inclusion of catalysts in pyrolysis has been reported to significantly enhance bio-oil and gas yields11,12. Recently, attention is focused on the use of urea as a catalyst due to its cost-effectiveness and environmental benefits. It promotes formation of bio-oil with improved functional group composition, increasing carbon content and heating value while reducing undesirable by-products like tar13. Additionally, compared to metal-based catalysts, urea is more stable under pyrolytic conditions14. It operates well at moderate temperatures, reducing energy requirements and minimizing biomass degradation15,16.

While several studies have explored bio-oil production from corncob pyrolysis at various temperatures, no consensus has been reached on an optimal temperature due to differences in corncob varieties. Although bio-oil produced from corncob has shown promising yields and energy content, further refinements such as the use of catalysts, torrefaction and co-pyrolysis are needed to improve its performance to levels comparable to fossil fuels17,18,19. Currently, there is limited research on the use of urea as a catalyst in biomass pyrolysis, and no studies have explored the impact of varying urea concentrations on corncob pyrolysis. This study aims to fill this research gap by identifying the optimum urea concentration and pyrolysis temperature for corncob pyrolysis to enhance yield, energy content, and chemical composition bio-oil.

Materials and methods

Source and preparation of corncobs

The corncobs used in this study were sourced from Dawib Farms in Sokoto, Nigeria. They were subjected to initial drying, crushing, and grinding, followed by sun-drying and sieving to achieve a uniform particle size of less than 200 µm. The resulting powder was then stored in an airtight container to prevent moisture absorption.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)/differential thermal analysis (DTA)

Corncob sample (6.5 mg) was placed in a crucible and transferred into PerkinElmer TGA4000 instrument utilized for the analysis. The experiment was conducted under inert conditions with a constant flow of nitrogen gas at a rate of 100 mL/min. The sample underwent heating at a rate of 15 °C/min in the temperature range of 20–800 °C. The resulting thermogravimetric data were compiled into a TGA curve. Additionally, the derivative DTA curve, obtained from the TGA curve was plotted.

Pyrolysis of corncob

The pyrolysis of corncob was carried out in a fixed-bed reactor (Fig. 1) under varying temperatures of 350 °C, 400 °C, and 450 °C based on thermal decomposition obtained from TGA/DTA curve. Briefly, 15 g of corncob powder was loaded into a glass reactor followed by nitrogen gas supply at a flow rate of 350 mL/min to create an inert atmosphere and ensure the purging of decomposition gases. Additionally, a coolant system was activated to circulate cold water through the condenser, facilitating the collection of condensable gases. A heating rate of 10 °C/min was employed until the reactor reached the target temperature to allow for better heat penetration into the feedstock. Additionally, higher heating rates may cause unwanted side reactions during pyrolysis. It was maintained for 45 min to ensure a complete collection of condensable gases. Thereafter, the reactor was cooled to room temperature before disassembly. The bio-oil produced was separated using dichloromethane in a 25 mL separating funnel, and its weight was recorded (Fig. 2). The biochar was recovered from the reactor and weighed, while the quantity of non-condensable gases was determined via a mass balance of the bio-oil and biochar. The conversion rate, reflecting the percentage of solids converted into liquid and gas products, was calculated using standard equations. The organic and aqueous phases of the bio-oil were stored separately in glass bottles, and the biochar was stored in aluminium foil to maintain sample integrity.

Schematic diagram of a fixed bed pyrolysis reactor20.

Subsequent pyrolysis experiments were conducted by incorporating urea at varying concentrations of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight (corresponding to 0.75 g, 1.5 g, 2.25 g, and 3.0 g of urea per 15 g of corncob respectively) using the optimal temperature identified in the initial set of experiments. The yields of bio-oil, biochar, and biogas were calculated as follows:

where W1 is the weight of the empty reactor, W2 is the weight of the reactor after the reaction, W3 is the weight of the empty measuring cylinder, and W4 is the weight of the measuring cylinder containing bio-oil.

Characterization of bio-oil

The chemical composition of the bio-oil samples was analysed using a Shimadzu FT-IR spectrometer (Model 8400S), which measured infrared absorption in the 600–4000 cm⁻1 range with a resolution of 4 cm⁻1. Ultimate analysis was performed using a CHNS analyser (Model NA 1500, Carlo Erba Instruments). The calorific value was determined through a bomb calorimeter (Model 6100, Parr Instrument Co., Moline, Illinois) while the gross heat of combustion was measured according to ASTM D2382-88 to obtain the heating value. Additionally, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) was employed to analyse the organic fraction of the bio-oil and the non-condensable gases produced during pyrolysis. The GC–MS analysis was conducted using an Agilent Intuvo 9000 GC system coupled with a 5977B MSD and equipped with a split injector.

Results and discussion

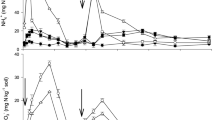

TGA/DTA curve for corncob

The TGA/DTA curve for corncob is presented in Fig. 3. The downward-sloping curves observed illustrate the weight loss in the feedstock which is an indication of thermal degradation of their lignocellulosic components. The TGA curve revealed an initial weight loss due to moisture evaporation, which is typically observed at temperatures below 100°C. Significant weight loss occurred between 200 and 400 °C, indicating decomposition of hemicellulose and cellulose. The DTA curve showed endothermic peaks corresponding to these decompositions. The residual weight after 400 °C reflects the charred remains of lignin and other components. This is an indication that major decomposition occurred around 400 °C which informed the choice range of 350–450 °C as the pyrolysis temperature for this study.

Impact of temperature on the yield of pyrolysis products

Figure 4 illustrates the yield of different products obtained from pyrolysis of corncob at temperatures of 350 °C, 400 °C, and 450 °C. The yield of bio-oil increased from 43.33% at 350 °C to a maximum of 48.67% at 400 °C, after which it declined to 44.67% at 450 °C. A corresponding reduction in biochar yield was observed, with a decrease from 38.00 wt.% at 350 °C to 28.33 wt.% at 450 °C, while biogas yield rose from 18.67 wt.% at 350 °C to 27.00 wt.% at 450 °C. The trend observed in the present study suggests that 400 °C is the optimal temperature for bio-oil production from corncob during pyrolysis. At this temperature, sufficient thermal energy was provided to effectively decompose the lignocellulosic structure of corncob without promoting excessive secondary cracking reactions that would lead to formation of non-condensable gases. The decline in bio-oil yield as temperature increased beyond 400 °C reflects a shift towards conversion of solid residues into gaseous products. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al.21 where thermal decomposition and volatilization of biomass components at higher temperatures led to higher gas production at the expense of bio-oil.

Effect of urea on the yield of pyrolysis products

The application of urea as a catalyst at 400 °C affected the yield of bio-oil, biochar, and biogas during the pyrolysis of corncob (Fig. 5). Without urea, the yield of bio-oil recorded was 49.33%. The introduction of 5% urea increased the yield to 53.00%, while a further increase to 10% urea resulted in a marginal boost, bringing the yield to 54.66%. However, raising the urea content beyond 10% caused a decline in bio-oil yield, with 15% and 20% urea resulting in yields of 53.33% and 52.00% respectively. This trend suggests that 10% urea represents the optimal concentration for maximizing bio-oil yield. The catalytic effect of urea in enhancing the breakdown of lignocellulosic bonds has been previously reported22. In this study, the relatively high bio-oil yield at 10% urea inclusion is an indication that this concentration is the optimal for bio-oil production from corncob. At this level, the elevated yield in bio-oil may be attributed to increased breakdown of lignocellulosic bonds in corncob.

Functional groups in bio-oil based on FT-IR analysis

The functional groups, as identified by FT-IR spectroscopy, in bio-oil samples with and without urea at the optimal concentration of 10% are depicted in Fig. 6. In the O–H and N–H stretching region (3649 cm−1 and 3388 cm−1), the bio-oil without urea exhibited narrower and less intense peaks, while the 10% urea-treated sample showed broader and more pronounced absorption. In the C–H stretching region (3000–2800 cm−1), the peaks were stronger and broader in the urea-treated bio-oil while both spectra showed peaks in the C=O stretching region (1650–1750 cm−1). The C=C stretching and N–H bending region (1600–1400 cm−1) displayed more pronounced peaks in the urea-treated bio-oil. The C–O stretching region (1000–1300 cm−1) revealed more significant peaks in the 10% urea sample compared to the untreated bio-oil while both samples exhibited intense peaks in the C–H bending region (1000–700 cm−1). The presence of N–H and O–H group activity in bio-oil produced with 10% urea concentration as revealed by FT-IR spectra may be an indication of enhanced hydroxyl and amine group interactions. This suggests a more chemically complex bio-oil with higher concentrations of valuable functional groups. In addition, aromatic compounds are known for their resistance to degradation and contribution to fuel quality23. Therefore, the increased aromaticity observed in bio-oil produced with urea as evidenced by pronounced peaks in the C=C stretching region points to improved stability of the product. Similarly, the strong C–O stretching peak as observed in this study which is associated with esters and amines has been reported to support reactivity and combustion efficiency of bio-oil24. These findings also align with those of Xiong et al.12 which reported improved fuel properties in bio-oil following addition of nitrogen-containing compounds. The reduction in bio-oil yield at urea concentration above 10% may be a result of secondary cracking reactions which favours gas production25.

Ultimate composition and higher heating value of bio-oil

Table 1 presents a comparison of the ultimate composition of bio-oil produced with and without urea, detailing carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur contents, along with their higher heating values (HHV). The carbon content increased from 84.80% in the untreated bio-oil to 86.40% in the urea-treated sample while hydrogen content reduced from 5.09 to 2.38% following treatment with urea. The level of nitrogen rose from 2.29 to 2.68%, while sulfur content dropped from 0.62 to 0.20%. Finally, oxygen content increased from 7.22 to 8.31% while the HHV also improved with urea addition, rising from 36.12 to 37.12 MJ/kg.

The increased carbon content in the urea-treated bio-oil is indicative of high energy potential and improved combustion efficiency22. This finding is significant as it brings the composition of bio-oil closer to that of conventional fuels like premium motor spirit (PMS) and diesel. However, the reduction in hydrogen content following urea addition may limit the performance of bio-oil as hydrogen is critical for cleaner combustion and high energy output26. The reduction in sulfur content is a positive outcome, potentially reducing SOx emissions in the environment. These findings agree with previous report that trade-offs between carbon and hydrogen content are crucial in optimizing bio-oil properties27.

The increase in nitrogen in the urea-treated bio-oil is particularly significant, as nitrogen-enriched bio-oils are often associated with improved thermal stability and higher calorific value, which enhance fuel performance28. These findings align with previous reports that nitrogen-based additives improve the nitrogen content of bio-oil. For instance, Xiong et al.12 reported that urea promotes formation of nitrogen-containing compounds during pyrolysis which enhances the quality of bio-oil. Li et al.29 also observed that urea and other nitrogen-rich compounds facilitate the conversion of biomass into nitrogen-enriched products, particularly pyridine derivatives. However, the potential for increased NOx emissions during combustion must be considered, as nitrogenous compounds can contribute to environmental concerns30.

HHV is a key indicator of fuel quality, as it represents the total energy released during combustion. An increase in HHV typically points to bio-oil with a higher proportion of carbon-rich compounds such as aromatic hydrocarbons and reduced oxygenated species, which are less energy-dense31. The increase in HHV observed in bio-oil produced with urea indicates an improvement in energy content. This aligns with findings from previous studies where bio-oil with increased aromaticity and reduced oxygen content demonstrated enhanced energy output32.

Chemical composition of bio-oil based on GC–MS analysis

The GC–MS analysis of bio-oil produced without urea revealed the presence of 100 compounds. All the compounds identified were eluted within retention times of 5.58 and 26.76 min with benzoquinoline, anthracene-2-carboxylic acid diethylamide and silicic acid as the major compounds (Table 2). By contrast, bio-oil produced with 10% urea contained 74 compounds as revealed by GC–MS analysis with the constituent compounds eluted with retention times between 7.08 and 34.10 min. Notably, siloxane compounds, which are valuable in bio-oil upgrading, were identified (Table 3).

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is a valuable technique that reveals the identity of compounds present in a sample33. GC–MS analysis of bio-oil produced with and without urea provides key insights into the catalytic role of urea in nitrogen retention and the overall quality of bio-oil produced. The presence of nitrogen-containing and oxygenated compounds notably siloxanes in the bio-oil produced with urea infusion may be an indication of stability and utility in chemical industries as these compounds are known for their significant role in bio-oil upgrading34. Siloxanes represent one of the many organic working fluids used in industries as heat transfer fluids for applications that require high temperature35,36. They are regarded as non-toxic and are characterized by different properties by virtue of their ability to occur in many configurations including linear, cyclic, or with methyl and phenyl groups. This assertion was supported by Di Marcoberardino et al.37 which reported that the addition of phenyl groups to siloxanes increased thermal stability. Another study by Vescovo38 also proposed the use of siloxanes in plant configurations at high-temperature due to their good thermal stability. Furthermore, the shift in composition following urea infusion is an indication that urea promotes not only nitrogen retention but also alters the profile of bio-oil to favour compounds that improve its value as a renewable resource39. The reduction in compound diversity in bio-oil produced with urea suggests a more targeted formation of nitrogenous compounds and loss of certain oxygenates that may have value in other applications.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the pyrolysis of corncob using urea as a catalyst, focusing on optimizing bio-oil yield and quality. The results indicated that 400 °C is the optimal pyrolysis temperature for maximizing bio-oil yield while minimizing biochar and gas production. A 10% urea concentration enhances bio-oil yield and improves its hydrocarbon content and energy density, making it a viable alternative to fossil fuels. Overall, urea-catalyzed pyrolysis of corncob presents a promising approach for sustainable bio-oil production, offering valuable insights for optimizing pyrolysis conditions and improving bio-oil quality. However, future studies could examine the use of other catalytic agents, such as metal-based or bio-based catalysts, in combination with urea in pyrolysis process.

Data availability

The data sets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (sakinabelobram@gmail.com).

References

Kumar, J. & Vyas, S. Comprehensive review of biomass utilization and gasification for sustainable energy production. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04127-7 (2024).

Rajesh Banu, J. et al. Lignocellulosic biomass based biorefinery: A successful platform towards circular bioeconomy. Fuel 302, 121086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121086 (2021).

Duan, D. et al. Corncob pyrolysis: Improvement in hydrocarbon group types distribution of bio oil from co-catalysis over HZSM-5 and activated carbon. Waste Manag. 141, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2022.01.028 (2022).

Pennington, D. Chapter 7—Bioenergy crops. In Bioenergy 2nd edn (ed. Dahiya, A.) 133–155 (Academic Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815497-7.00007-5.

Louis, A. C. F. & Venkatachalam, S. Energy efficient process for valorization of corn cob as a source for nanocrystalline cellulose and hemicellulose production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 163, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.276 (2020).

FAO. FAO at the 2024 Global Forum for Food and Agriculture. REU, accessed 19 July 2024; https://www.fao.org/europe/events/detail/fao-at-the-2024-global-forum-for-food-and-agriculture/en.

National Bureau of Statistics. Reports | National Bureau of Statistics, accessed 19 July 2024; https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/1241515.

Amenaghawon, A. N., Anyalewechi, C. L., Okieimen, C. O. & Kusuma, H. S. Biomass pyrolysis technologies for value-added products: A state-of-the-art review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23(10), 14324–14378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01276-5 (2021).

Singh, S. & Sawarkar, A. Pyrolysis of corn cob: Physico-chemical characterization, thermal decomposition behavior and kinetic analysis. Chem. Prod. Process Model. 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.1515/cppm-2020-0048 (2020).

Janewit, W., Worasuwannarak, N. & Pipatmanomai, S. Product yields and characteristics of rice husk, rice straw and corncob during fast pyrolysis in a drop-tube/fixed-bed reactor. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 30, 393 (2008).

Wu, P. et al. Urea assisted pyrolysis of corn cob residue for the production of functional bio-oil. J. Energy Inst. 101, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2022.01.008 (2022).

Xiong, J. et al. Research progress on pyrolysis of nitrogen-containing biomass for fuels, materials, and chemicals production. Sci. Total Environ. 872, 162214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162214 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Effects of temperature and urea concentration on nitrogen-rich pyrolysis: Pyrolysis behavior and product distribution in bio-oil. Energy 239, 122443. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2021.122443 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Catalytic co-pyrolysis of Chlorella vulgaris and urea: Thermal behaviors, product characteristics, and reaction pathways. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 167, 105667. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAAP.2022.105667 (2022).

Yin, M. et al. Production of bio-oil and biochar by the nitrogen-rich pyrolysis of cellulose with urea: Pathway of nitrile in bio-oil and evolution of nitrogen in biochar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 174, 106137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106137 (2023).

Masjedi, S. K., Kazemi, A., Moeinnadini, M., Khaki, E. & Olsen, S. I. Urea production: An absolute environmental sustainability assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168225 (2024).

Dai, L. et al. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of torrefied corn cob to aromatic hydrocarbons over Ni-modified hierarchical ZSM-5 catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 272, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.10.062 (2019).

Klaas, M. et al. The effect of torrefaction pre-treatment on the pyrolysis of corn cobs. Results Eng. 7, 100165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2020.100165 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. Insight into product characteristics from microwave co-pyrolysis of low-rank coal and corncob: Unraveling the effects of metal catalysts. Fuel 342, 127860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127860 (2023).

Balasundram, V. et al. Catalytic pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse over cerium (rare earth) loaded HZSM-5 zeolite. Energy Procedia 142, 801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.12.129 (2017).

Zhang, X., Zhang, P., Yuan, X., Li, Y. & Han, L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and correlation analysis on the yield and physicochemical properties of crop residue biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 296, 122318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122318 (2020).

Dada, T. K., Sheehan, M., Murugavelh, S. & Antunes, E. A review on catalytic pyrolysis for high-quality bio-oil production from biomass. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 13(4), 2595–2614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-01391-3 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Bio-oil from biomass fast pyrolysis: Yields, related properties and energy consumption analysis of the pyrolysis system. J. Clean. Prod. 328, 129613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129613 (2021).

Chantanumat, Y. et al. Characterization of bio-oil and biochar from slow pyrolysis of oil palm plantation and palm oil mill wastes. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 13(15), 13813–13825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-02291-2 (2023).

Abou Rjeily, M., Gennequin, C., Pron, H., Abi-Aad, E. & Randrianalisoa, J. H. Pyrolysis-catalytic upgrading of bio-oil and pyrolysis-catalytic steam reforming of biogas: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19(4), 2825–2872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01190-2 (2021).

Jain, R., Panwar, N. L., Agarwal, C. & Gupta, T. A comprehensive review on unleashing the power of hydrogen: Revolutionizing energy systems for a sustainable future. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33541-1 (2024).

Habib, M. A., Abdulrahman, G. A. Q., Alquaity, A. B. S. & Qasem, N. A. A. Hydrogen combustion, production, and applications: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 100, 182–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.05.030 (2024).

Ilyin, S. O. & Makarova, V. V. Bio-oil: Production, modification, and application. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 58(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10553-022-01348-w (2022).

Li, S.-X., Chen, C.-Z., Li, M.-F. & Xiao, X. Torrefaction of corncob to produce charcoal under nitrogen and carbon dioxide atmospheres. Bioresour. Technol. 249, 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.10.026 (2018).

Iavarone, S. & Parente, A. NOx Formation in MILD combustion: Potential and limitations of existing approaches in CFD. Front. Mech. Eng. 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2020.00013 (2020).

Noushabadi, A. S., Dashti, A., Ahmadijokani, F., Hu, J. & Mohammadi, A. H. Estimation of higher heating values (HHVs) of biomass fuels based on ultimate analysis using machine learning techniques and improved equation. Renew. Energy 179, 550–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.07.003 (2021).

Dhyani, V. & Bhaskar, T. A comprehensive review on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Energy 129, 695–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.04.035 (2018).

Uthman, T. O., Salman, R. Y. & Lamorde, I. A. Free radical scavenging activity of alkaloid and flavonoid fractions of Kalanchoe pinnata leaves. J. Drug Des. Med. Chem. 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jddmc.20230901.12 (2023).

Dai, L. et al. Bridging the relationship between hydrothermal pretreatment and co-pyrolysis: Effect of hydrothermal pretreatment on aromatic production. Energy Convers. Manag. 180, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.10.079 (2019).

Schuster, A., Karellas, S., Kakaras, E. & Spliethoff, H. Energetic and economic investigation of Organic Rankine Cycle applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 29, 1809–1817 (2009).

Rettig, A. et al. Application of Organic Rankine Cycles(ORC). In Proceedings of the World Engineer’s Convention. (Geneva, Switzerland, 2011).

Di Marcoberardino, G. et al. Thermal stability and thermodynamic performances of pure siloxanes and their mixtures in organic Rankine Cycles. Energies 15, 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103498 (2022).

Vescovo, R. High Temperature Organic Rankine Cycle (HT-ORC) for Cogeneration of Steam and Power. (AIP, Melville, NY, USA, 2019).

Gea, S. et al. A comprehensive review of experimental parameters in bio-oil upgrading from pyrolysis of biomass to biofuel through catalytic hydrodeoxygenation. BioEnergy Res. 16(1), 325–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-022-10438-w (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.I. conceptualized the study, designed experiments, and wrote the original draft. T.O.U. contributed to data analysis, supervision and manuscript review. S.S. Data Analysis, Proofreading and supervision A.M.S. supervised the research at the laboratory.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bello, S.I., Uthman, T.O., Surgun, S. et al. Urea enhances the yield and quality of bio-oil produced from corncob through pyrolysis. Sci Rep 15, 2990 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86800-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86800-7