Abstract

We use digital quantum computing to simulate the creation of particles in a dynamic spacetime. We consider a system consisting of a minimally coupled massive quantum scalar field in a spacetime undergoing homogeneous and isotropic expansion, transitioning from one stationary state to another through a brief inflationary period. We simulate two vibration modes, positive and negative for a given field momentum, by devising a quantum circuit that implements the time evolution. With this circuit, we study the number of particles created after the universe expands at a given rate, both by simulating the circuit and by actual experimental implementation on IBM quantum computers, consisting of hundreds of quantum gates. We find that state-of-the-art error mitigation techniques are useful to improve the estimation of the number of particles and the fidelity of the state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gravity is probably a quantum field1,2 but we don’t know yet how to completely fit it into Quantum Field Theory. Standard quantization of General Relativity leads to a nonrenormalizable theory and alternate approaches are far from making falsifiable predictions.

We can take a more modest path, where spacetime is kept as a classical background and is coupled to the quantum fields. This semiclassical approximation is known as Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime (QFTCS). In this way, we maintain a classical but curved gravitational background, which serves as the stage on which we place the matter fields, which are quantized. The most famous application of QFTCS is probably Black Hole Thermodynamics, which includes Hawking Radiation3. Other examples are the Unruh Effect4, Hawking’s Chronology Protection Conjecture5 or cosmological particle creation in expanding spacetimes6,7,8.

However, these predictions are extremely hard to check experimentally, which suggests the interest of using simulators. For instance, the simulation of Hawking radiation has been successfully achieved in the laboratory with Bose–Einstein condensates9 and many theoretical proposals with superconducting circuits or other quantum setups can be found in the literature10,11. In particular, cosmological models of expanding spacetimes has been also simulated in the laboratory12,13. In comparison to these analogue quantum simulations, it seems that the possibility of digital quantum simulation of QFTCS has been much less explored.

Digital quantum computers have undergone spectacular improvements over the last years, quickly progressing from few-qubit academic demonstrations to the current setups with tens or hundreds of qubits. Despite impressive improvements in the error rates, the current scenario can still be characterized as the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era14, where on the one hand quantum error correcting codes are still not operational and thus the lack of fault tolerance prevents the elusive dream of universal quantum computing, while on the other hand useful particular tasks beyond the classical computer capabilities are still out of reach, other than tailor-made examples with no clear application—the quantum supremacy paradigm15,16,17. However, it has been recently been claimed that the use of error mitigation18,19,20 techniques—instead of quantum error-correcting codes—can make current NISQ computers give reliable and useful estimations of expectation values of observables of interest beyond the capabilities of classical computer—a notion called quantum utility21. In this work, we show that a current quantum computer can provide an estimation of the number of particles generated in a model of expanding spacetime. We present results for the number of particles generated and the fidelity of the state in a quantum circuit containing hundreds of quantum gates, which simulates the time evolution of two modes of a quantum field under the spacetime dynamics. We use both IBM simulators and real quantum computers. Despite the large amount of gates, we show that the use of zero-noise extrapolation21 allows us to reach interesting predictions even in the actual quantum devices with their current levels of noise.

In “Model” section we explain the details of the model that we digitize in “Digitization” section. We present the results of simulations and experiments in “Results: number of particles” and “Results: fidelity” sections.

Model

We will follow the toy model provided in Ref.22. The infinitesimal line element ds, whose coefficients determine the metric of the spacetime, in a Friedman–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker universe is given by Refs.23,24,25,26,27,28,29:

where a(t) is the scale factor, which only depends on time.

We can make a change of variables to conformal time, such that \(d\eta =\frac{dt}{a(t)}\), so the metric in these coordinates becomes:

where \(C(\eta )=a^2(\eta )\), which is obtained by substituting time t for conformal time \(\eta\) through solving the following integral:

We work in a universe that evolves from a stationary state where \(C(-\infty )=A-B\) to a new stationary state where \(C(\infty )=A+B\) through \(C(\eta )=A+B\tanh (\rho \eta )\), where \(\rho >0\) is a constant that codifies the transition velocity (see Fig. 1). The universe expands if \(B>0\), contracting otherwise. The value of \(C(\eta )\) must always be positive, so \(A>|B|\).

On this gravitational background, we place a free scalar field with mass m, that is, it evolves over time through the Klein–Gordon equation30,31:

This partial differential equation can be solved by separation of variables, with a solution for each mode of the form:

with \(\chi _k(\eta )\) satisfying:

whose solution is given by hypergeometric functions.

We are particularly interested in the behavior of the field in the limits \(\eta \rightarrow \pm \infty\), which is given by:

where \(\omega _{in}=\sqrt{k^2+m^2(A-B)}\) and \(\omega _{out}=\sqrt{k^2+m^2(A+B)}\). These two limits are of special interest because \(\omega _{out}\), the frequency of the free field after the expansion, is the frequency that will appear in the Hamiltonian governing the time evolution of the field after the universe expands. Additionally, together with \(\omega _{in}\), these are the frequencies that are needed to relate the vibrational modes of the field before and after the expansion, which is crucial for computing the number of particles created by the expansion of the universe.

Clearly, the vibration modes of the field are not the same before and after a short period of inflation. Initially, the field is stationary in the vacuum state \({|{0, in}\rangle }\). After the inflationary evolution, however, this state is not going to be an eigenstate of the time evolution anymore, so we could detect a number of particles different from zero and study their evolution over time.

We have chosen this model because the vibration modes of the field before inflation can be easily related to those after inflation, in the sense that the vibrations with momentum k mix only with their opposite \(-k\), but not with other configurations with different |k|. The Bogoliubov transformations that relate the vibration modes \(\phi ^{in}\) and \(\phi ^{out}\) are given by:

where the coefficients \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are complex functions of \(\omega _{in}\), \(\omega _{out}\) and \(\rho\)22:

with \(\omega _\pm =\frac{1}{2}\left( \omega _{out}\pm \omega _{in}\right)\).

The reason why we are using this toy model to simulate the cosmological particle production is because its simplicity allows us to write an analytical expression for the Bogoliubov coefficients, which relate the vibrational modes of the field, and its respective quantized observables, before and after the expansion. For other models whose relationship between modes is not known, it is not possible to perform such simulations. Furthermore, in more general models of QFTCS, the number of particles is not well-defined, depending on the observer measuring it. A classical example of this is black hole thermal radiation, which is zero for a near-horizon freely falling observer, but non-zero for a stationary one. In contrast, our model allows us choose an observer who initially detects the vacuum and study the particle creation from its perspective.

When quantizing the field, we use the annihilation and creation operators \(a_+\) and \(a_+^\dagger\) for the in modes of positive k, and \(a_-\) and \(a_-^\dagger\) for the in modes of negative k. These creation and annihilation operators are related to the annihilation and creation operators of the out modes, which we call \(b_+\), \(b_+^\dagger\), \(b_-\) and \(b_-^\dagger\), using the same Bogoliubov coefficients32,33:

Now, the generator of the time evolution of these two positive and negative modes is the Hamiltonian:

In the interaction picture, an initial vacuum state will evolve under the interaction hamiltonian:

Thus the time evolution operator in this picture is:

We are interested in the number of particles—as defined before the expansion by the in operators- created after the expansion as a function of the expansion rate \(\rho\).

This type of particle creation process due to a non-flat metric can be interpreted as if the field were in thermodynamic equilibrium with a thermal source34,35. Therefore, the state predicted by quantum field theory for the time evolution operator 15 applied to an initial vacuum is a state well-known in quantum optics—two-mode squeezed state36 where \(2 \alpha \beta ^* \omega _{out} t\) is the squeezing parameter. When the trace over one mode is taken over a two-mode squeezed state, a single-mode thermal state with squeezing-dependent temperature is obtained37, giving rise to:

Therefore, the expected number of particles created can be calculated as:

As we will see below, we will restrict ourselves to only one created particle per mode. The state restricted to one excitation can be obtained by taking the first two terms of the sum in (16) and renormalizing, giving rise to:

Digitization

To simulate the system, we assign the first two qubits to the activation of the positive mode, and the last two to the negative mode38. Therefore, we assign \({|{0101}\rangle }\) to the state \({|{0, in}\rangle }\), the qubit \({|{1001}\rangle }\) to the state \({|{1_+, in}\rangle }\), the qubit \({|{0110}\rangle }\) to the state \({|{1_-, in}\rangle }\), and the qubit \({|{1010}\rangle }\) to the state \({|{1_+1_-, in}\rangle }\). This means that we are restricting ourselves to only one excitation per mode.

In this qubit basis, the creation and annihilation operators map to:

where the matrices \(\sigma _\pm\) are given by:

Under this qubit mapping, the interaction Hamiltonian (14) is written as:

Using (21), we write the operators in terms of Pauli matrices:

where

and

Therefore, the temporal evolution operator would be given by the complex exponential of the following interaction Hamiltonian:

Note that all terms within A and B commute with each other, while the commutator of A and B only has two non-zero diagonal terms that merely add an irrelevant phase to the initial vacuum state. Therefore the decomposition into exponential products is exact up to second order in \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) and no further use of Trotter techniques is required.

Thus by factorizing the time evolution we get something of the form:

Now we have to decompose these multiqubit interactions into single and two-qubit gates. To this aim we resort to the following decomposition39,40,41,42:

and, in case we have a gate y instead of a gate x acting on qubit i, we introduce a rotation matrix to change the y into x as follows:

The two-qubit gates can be translated to CNOT gates, by using:

except for a global phase that we disregard.

Now that we have the operator \(\sigma _a^0\sigma _b^1\sigma _c^2\sigma _d^3\) written in the following form:

with M a unitary matrix, which is given by the Eqs. (28) and (29), we can take exponentials in both sides to find:

where k is the coefficient accompanying that operator in the temporal evolution, which can be \(-\frac{1}{4}\omega _{out}t\textrm{Re}(\alpha \beta ^*)\) or \(\frac{1}{4}\omega _{out}t\textrm{Im}(\alpha \beta ^*)\).

The operator left in the middle is simply a qubit rotation around the z axis whose rotation angle depends on the coefficients \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) the therefore on the expansion rate \(\rho\).

For example, for the case \(\sigma _x^0\sigma _x^1\sigma _y^2\sigma _y^3\), the contribution to the temporal evolution is:

where, in the last step, Eq. (30) has been used, many simplifications have been made, and it has been written in terms of matrices S and RX in order to express it in the language of IBM quantum computers.

This circuit can be observed in Fig. 2. In addition to this, there are 15 other similar circuits corresponding to the 16 operators in the Eq. (26). Finally, we need to place two gates \(X_1\) and \(X_3\) at the beginning to initialize the state \({|{0, in}\rangle }={|{0101}\rangle }\) The complete circuit can be seen in Fig. 3 including two z-axis measurement gates at the end to measure the number of particles in one of the two modes. The latter serves to visualize that we are only measuring the number of particles of one mode, however what we actually do in the experiments is to use the IBM primitive estimator for the computation of four-qubit expectation values and tomographycally reconstruct the probability of excitation of a single mode—see more details in the next section.

Results: number of particles

To carry out the simulation, we set \(A=1.5\) and \(B=0.5\), such that we evolve from a universe with \(C=1\) to a universe with \(C=2\) with a variable value of \(\rho\), ranging from \(\rho =0.01\) to \(\rho =100\), to study the number of particles generated in a time of \(t=1\). Also, we set the mass of the field to \(m=1\).

Since the vibration modes do not mix, we study a single excited state of the field, with \(|k|=1\), so the vibration frequencies are \(\omega _{in}=\sqrt{2}\), \(\omega _{out}=\sqrt{3}\), \(\omega _+=\frac{1}{2}\left( \sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2}\right)\), and \(\omega _-=\frac{1}{2}\left( \sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2}\right)\).

Given that both the positive and negative modes are equivalent, we only measure the number of particles in two out of the four qubits we use. A measurement of \({|{01}\rangle }\) in these two qubits represents that we measured the field without any particles, while a measurement of \({|{10}\rangle }\) means that we measured a particle in that mode. The states \({|{00}\rangle }\) and \({|{11}\rangle }\) have no physical meaning. Therefore, the number of particles of, for instance, the second mode would be given by the probabilities of \({|{1010}\rangle }\) and \({|{0110}\rangle }\). In order to be able to benefit from error mitigation techniques, we need to use estimator, and therefore we need to estimate the expectation values of the following seven observables \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes I\otimes Z}\right\rangle ,\) \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes Z\otimes I}\right\rangle ,\) \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes Z\otimes Z}\right\rangle ,\) \(\left\langle {Z\otimes Z\otimes I\otimes I}\right\rangle ,\) \(\left\langle {Z\otimes Z\otimes I\otimes Z}\right\rangle ,\) \(\left\langle {Z\otimes Z\otimes Z\otimes I}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {Z\otimes Z\otimes Z\otimes Z}\right\rangle\), which allow the tomographic reconstruction of the aforementioned sum of probabilities.

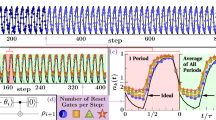

To obtain results, we conducted three batches of experiments, each batch consisting in several executions of the circuit over a range of values of \(\rho\). First, we performed them with the AerSimulator simulator provided by IBM. As can be seen in Fig. 4, the simulated values are arranged between the theoretical values for infinite particles and one particle, calculated with Eqs. (17) and (18), showing the suitability of our quantum circuit.

Furthermore, we realized actual experiments on the IBM 127-qubit Eagle-processor quantum computer called \(ibmq\_osaka\)—which, at the time of the realization of the experiments was one of the computers with the lowest error rates available, see more details below—with the use of zero-noise extrapolation (ZNE), a state-of-the-art error mitigation technique18,19,20. Results are quite noisy and tend to overestimate the number of particles for negative and small values of \(x\equiv \log {\rho }\), but seem to converge to the correct ones for the largest values of the expansion rate parameter. To obtain more accurate results, it may be necessary to improve the noise removal of the IBM quantum gates or develop better error mitigation techniques.

As a technical remark, we note that we didn’t use the highest level of circuit optimization along none of the experiments, since we found that for negative and small values of x the value of the circuit parameters was so low that they were neglected and therefore the experiments were finally just trivial executions of the identity. While this would get us close to the theoretical predictions—which are basically 0 in that parameter range, as can be seen in the Figure—that would of course not be a consequence of any property of the actual quantum hardware. Therefore, we chose to decrease the optimization level, resulting in actual executions of quantum circuits with very small rotation parameters.

Results: fidelity

In order to complement and further illuminate the results for the number of particles, we will now compute the fidelity:

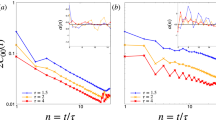

between the state \(\rho\), calculated from a second-order Taylor expansion of expression (15), and the density matrix \(\sigma\) obtained from experimental state tomography. In particular, we focus on the two qubits representing one mode. Fidelity is a measurement of the distance between two quantum states, being 1 if both density matrices represent the same states, and 0 if the states are orthogonal and therefore it can be a useful figure of merit in quantum simulation, by using it to compare the experimental outcome with a theoretical prediction. After some algebra, we find that, up to first order to find in \(\omega _{out}t\):

Therefore, we only need to measure experimentally the expectation values of three observables: \(\left\langle {I\otimes Z}\right\rangle\), \(\left\langle {Z\otimes I}\right\rangle\), and \(\left\langle {Z\otimes Z}\right\rangle\). We do so for a range of values of \(\rho\), with and without error mitigation (ZNE, which characterizes the noise in the experiment and tries to capture its relationship with the results, in order to provide an estimation of the noiseless result), as can be seen in Fig. 5. Notice that in order to use estimator, the two-qubit observables would be actually the four-qubit ones, with the identity matrix in the two extra qubits, namely \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes I\otimes Z}\right\rangle\), \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes Z\otimes I}\right\rangle\), and \(\left\langle {I\otimes I\otimes Z\otimes Z}\right\rangle\).

Notice that, without error mitigation, the fidelity is extremely low, as expected from the large number of gates. In particular, to execute our circuit on the IBM Osaka quantum computer, 96 2-qubit gates are used, each with an average associated error of \(6.741 \times 10^{-3}\), and 226 1-qubit gates, each with an average error of \(4.238 \times 10^{-4}\). This is for the estimation of the expectation value of a single observable, and therefore the procedure has to be performed three times, one for each observable of interest. Assuming that the error would grow as \(e^{-n\varepsilon }\) where n is the number of gates and \(\varepsilon\) the average gate error, we expect an error of approximately 52% in the value of each observable. However, we see in Fig. 5 that the use of error mitigation can significantly improve these poor values of the fidelity.

Summary and conclusions

We use digital quantum computing to simulate the creation of particles by the dynamics of an expanding spacetime. By means of a boson-qubit mapping, we digitize a system consisting of two modes of a massive quantum scalar field in a spacetime undergoing homogeneous and isotropic expansion, transitioning from one stationary state to another through an inflationary period. We study the number of particles created after some interaction time as a function of the expansion rate, both by simulating the circuit and by actual experimental implementation on IBM quantum computers. The circuit consists of a few hundred of quantum gates. We find that state-of-the-art error mitigation techniques such as ZNE are useful to improve the estimation of the number of particles and the fidelity of the state.

Quantum computing is still in a very early stage. It is said that we are living in the NISQ era, in which quantum technology, such as computers, is not yet large enough in terms of qubit size to surpass the power of classical computers, and is too noisy to be used for reasonably long computations, like the one we have done in this work.

In terms of size, some of IBM’s quantum processors, such as Condor with its 1121 qubits, have already surpassed the threshold of what a classical computer can do. However, noise, as we have seen in this work, remains an unresolved issue.

Using only 4 qubits, we have built a circuit to simulate a quantum field placed on a gravitational background, limiting ourselves to just one excitation of the ground state. We could continue to include excited states by simply adding more qubits, but this would require many more gates, causing more noise and reducing fidelity, making it impossible to use the circuit for physical predictions. One of the short-term goals in the field of quantum computing is precisely this: achieving a quantum simulation of a physical system that cannot be done with a classical computer. Unfortunately, this necessarily depends on improving the efficiency of existing quantum computers. In our four-qubit example the use of error mitigation techniques helped to alleviate the issue, as in a recent example with 127 qubits and only three layers of gates21. Whether this would be still the case in a problem combining both large qubit number and large circuit depth remains an open issue. While we do not have unrestricted access to a state-of-the-art large quantum device at the moment, our preliminary few-qubit results can be seen as a first step towards this sort of experiments, as we discussed in more detail below.

Although the interaction that was presented here can be studied analytically, it would be computationally harder to do so with more modes or excitations per mode, which would essentially require the same techniques described here. For instance, with the currently available 127-qubit computers, we could consider more than 50 excitations per mode, which would also allow us to use a wider range of parameters. These experiments would presumably enter into the post-classical regime, since it is known that circuits with more than 100 qubits and enough circuit depth are computationally very hard for classical computers. However, even considering the improvements in reducing error rates, it is likely that it would not be enough to compensate for the dramatic improvement in the number of quantum gates that would be required to simulate such a large number of excitations. Therefore, as commented above, it would be necessary to check if ZNE could still render useful results for both large number of qubits and large circuit depth. Since we do not have unrestricted access to a large quantum computer at the moment, the question lies beyond the scope of this paper and remains open for future investigation. If answered successfully, it would show the utility of a quantum computer to realize a computation of fundamental interest beyond the typical approximations employed classically.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Woodard, R. P. How far are we from the quantum theory of gravity?. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72(12), 126002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/72/12/126002 (2009).

Bose, S. et al. Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119(24), 401. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.119.240401 (2017).

Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 43(3), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02345020 (1975).

Unruh, W. G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 14, 870–892. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.14.870 (1976).

Hawking, S. W. Chronology protection conjecture. Phys. Rev. D 46, 603–611. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.46.603 (1992).

Parker, L. Quantized fields and particle creation in expanding universes. i. Phys. Rev. 183, 1057–1068. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.183.1057 (1969).

Parker, L. Quantized fields and particle creation in expanding universes. ii. Phys. Rev. D 3, 346–356. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.3.346 (1971).

Parker, L. Thermal radiation produced by the expansion of the universe. Nature 261(5555), 20–23 (1976).

Steinahuer, J. Observation of quantum hawking radiation and its entanglement in an analogue black hole. Nat. Phys. 12, 959. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3863 (2016).

Nation, P. D., Johansson, J. R., Blencowe, M. P. & Nori, F. Colloquium: Stimulating uncertainty: Amplifying the quantum vacuum with superconducting circuits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1 (2012).

Hu, J., Feng, L., Zhang, Z. & Chin, C. Quantum simulation of unruh radiation. Nat. Phys. 15(8), 785–789 (2019).

Steinhauer, J. et al. Analogue cosmological particle creation in an ultracold quantum fluid of light. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 2890 (2022).

Viermann, C. et al. Quantum field simulator for dynamics in curved spacetime. Nature 611(7935), 260–264 (2022).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the nisq era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574(7779), 505–510 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Strong quantum computational advantage using a superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127(18), 180501 (2021).

Brooks, M. Beyond quantum supremacy: the hunt for useful quantum computers. Nature 574(7776), 19–22 (2019).

Li, Y. & Benjamin, S. C. Efficient variational quantum simulator incorporating active error minimization. Phys. Rev. X 7, 5 (2017).

Temme, K., Bravyi, S. & Gambetta, J. M. Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119(18), 3 (2017).

Kandala, A. et al. Error mitigation extends the computational reach of a noisy quantum processor. Nature 567(7749), 491–495 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618(7965), 500–505 (2023).

Birrel, N. D. & Davies, P. C. W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space 59–62 (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Friedmann, A. Über die krümmung des raumes. Z. Phys. 10, 377–386 (1922).

Friedmann, A. Über die möglichkeit einer welt mit konstanter negativer krÃmmung des raumes. Z. Phys. 21(1), 326–332 (1924).

Lemaître, G. Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques. Ann. Soc. Sci. Bruxelles 47, 49–59 (1927).

Robertson, H. P. Kinematics and world-structure. Astrophys. J. 82, 284 (1935).

Robertson, H. P. Kinematics and world-structure ii. Astrophys. J. 83, 187 (1936).

Robertson, H. P. Kinematics and world-structure iii. Astrophys. J. 83, 257 (1936).

Walker, A. G. On Milne’s theory of world-structure. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 2–42, 90–127 (1937).

Klein, O. Quantentheorie und fünfdimensionale relativitätstheorie. Z. Phys. 37, 895–906 (1926).

Gordon, W. Der comptoneffekt nach der schrödingerschen theorie. Z. Phys. 40, 117–133 (1926).

Bogoljubov, N. N., Tolmachov, V. V. & Širkov, D. V. On a new method in the theory of superconductivity. Fortschr. Phys. 6, 605–682 (1958).

Valatin, J. G. Comments on the theory of superconductivity. Nuovo Cimento 7, 843–857 (1958).

Hawking, S. W. Black hole explosions?. Nature 248, 30–31 (1974).

Unruh, W. G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 14, 870–892 (1976).

Schumaker, B. L. & Caves, C. M. New formalism for two-photon quantum optics. ii. Mathematical foundation and compact notation. Phys. Rev. A 31, 3093–3111. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.31.3093 (1985).

Yurke, B. & Potasek, M. Obtainment of thermal noise from a pure quantum state. Phys. Rev. A 36, 3464–3466. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.36.3464 (1987).

Somma, R., Ortiz, G., Knill, E. & Gubernatis, J. Quantum simulations of physics problems. Int. J. Quant. Inf. 1(2), 189–206 (2003).

Sabín, C. Digital quantum simulation of linear and nonlinear optical elements. Quant. Rep. 2, 208–220 (2020).

Encinar, P. C. et al. Digital quantum simulation of beam splitters and squeezing with ibm quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 104, 1 (2021).

Sabín, C. Digital quantum simulation of quantum gravitational entanglement with ibm quantum computers. EPJ Quant. Technol. 10, 1 (2023).

Rufo, P. G. C., Mazumdar, A., Bose, S. & Sabín, C. Digital quantum simulation of gravitational optomechanics with ibm quantum computers. EPJ Quant. Technol. 11, 370 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sieglinde Pfaendler for her help and support.

Funding

We acknowledge the use of IBM Quantum Credits for this work. The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not reflect the official policy or position of IBM or the IBM Quantum team. C.S. acknowledges financial support through the Ramón y Cajal Programme (RYC2019-028014-I).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS suggested and supervised the project. MDM made the computations, programmed and launched the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the first version of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the final writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maceda, M.D., Sabín, C. Digital quantum simulation of cosmological particle creation with IBM quantum computers. Sci Rep 15, 3476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87015-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87015-6