Abstract

Obstetric fistula is a major maternal health challenge in low-income countries like Ethiopia. Misperceptions about obstetric fistula delay seeking and accessing healthcare. Understanding community attitudes is crucial for prevention, early detection, and support for affected women. A community-based study was conducted from February 1 to April 26, 2024, among 640 women and men to assess attitudes and influencing factors. Participants were selected using a multistage sampling. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The study included nearly equal proportions of males (49.1%) and females (50.9%), with a median age of 32 years (IQR: 19–64). Among participants, 47.8% (95%CI: 43.7–51.6) had a favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula. Those under 20 years (AOR: 7.7; 95%CI: 2.3–28.6), aged 20–35 (AOR: 3.9; 95%CI: 1.8–8.5), and aged 36–50 (AOR: 6.36; 95%CI: 3.0–14.1) were more likely to have a favourable attitude compared to those over 50 years. Female gender (AOR: 1.5; 95%CI: 1.1–2.2), primary education (AOR: 1.86; 95%CI: 1.3–2.9), and awareness of obstetric fistula (AOR: 3.04; 95%CI: 2.0–4.6) were significant determinants. The study revealed unfavourable community attitudes towards obstetric fistula, with notable gender and age differences. Enhancing attitudes requires a comprehensive, tailored program involving all relevant stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstetric fistula is a serious condition resulting from prolonged or obstructed labour, leading to an abnormal opening between the vagina and the urinary tract or rectum1. This condition is a common and devastating maternal health issue globally, particularly affecting women in resource-limited settings. It is estimated that 2 to 3.5 million women worldwide live with obstetric fistula, with approximately 2 million cases untreated2. The presence of obstetric fistula often reflects the challenges faced in maternal healthcare in low-resource settings, highlighting the urgent need for improved obstetric care to prevent and address this significant issue1,3.

Women affected by obstetric fistula frequently experiences social exclusion and significant health challenges, including urinary and faecal incontinence4,5. Despite its elimination in wealthier countries through high-quality maternity care, millions of new cases continue to emerge annually in resource-poor nations6. Prevention relies on accessible and respectful obstetrical care, driven by trust and positive attitudes7. Ethiopia, for instance, is actively working to address fistula through prevention and treatment strategies, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals for 20308,9,10.

An unfavourable attitude towards obstetric fistula within a community can have devastating consequences11,12. Stigmas surrounding contraception and early childbearing can lead to misconceptions about prevention methods and hinder access to proper reproductive health services13. This lack of accurate knowledge may result in affected women seeking ineffective treatments or avoiding seeking medical help altogether14. Such attitudes not only perpetuate the cycle of misinformation but also contribute to the physical, emotional, and social burden faced by women suffering from obstetric fistula8. Addressing these negative attitudes and promoting accurate information is essential in alleviating the burden of this preventable condition on individuals and communities9,10,15,16.

Studies highlights unfavourable attitude towards preventing obstetric fistula in Sub-Saharan Africa, influenced by societal stigmas against contraception and early childbearing7,17. Misconceptions persist, with beliefs in traditional remedies and avoiding sexual activities as prevention methods. These misconceptions hinder the uptake of reproductive health services and may lead affected women to seek alternative treatments18,19. Addressing these misconceptions is crucial for improving reproductive health outcomes in the region20,21,22. Unfavourable attitudes toward obstetric fistula within a community can be influenced by several risk factors. A lack of awareness and education about the condition can lead to stigma and misconceptions, causing women to suffer in silence23,24. Cultural beliefs and traditions may also perpetuate negative attitudes, as some communities may view obstetric fistula as a punishment or curse. Additionally, social and economic factors such as poverty and gender inequality can further marginalize women with obstetric fistula, hindering their ability to seek help and support8,25,26,27,28,29,30.

Understanding the risk factors associated with unfavourable attitudes toward obstetric fistula within a community is crucial in Ethiopia to address gaps in evidence and enhance the access to care for affected women. By researching community attitudes, specific cultural beliefs, misconceptions, and social barriers contributing to stigma and discrimination can be identified. This information can help policymakers and healthcare providers craft targeted interventions and awareness campaigns to challenge these negative attitudes and foster acceptance and support for women with obstetric fistula. Moreover, research can shed light on the influence of socioeconomic factors and healthcare accessibility on community attitudes, guiding efforts to improve maternal health services and ensure timely treatment for women living with obstetric fistula. However, there is a significant gap in the available evidence regarding the community`s understanding and attitudes towards obstetric fistula and its influencing factors in northwest Ethiopia, highlighting the need to assess and address this gap to provide better support for affected individuals and reduce the prevalence of fistula cases. Therefore, this study aimed to assess community attitudes towards obstetric fistula and identify contributing factors among adults residing in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and period

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted from 1st February 2024 to 26th April 2024 to determine the community`s attitudes towards obstetric fistula and identify its determinants.

Study setting

The study was carried out in Gondar city, situated in the Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. Gondar city is composed of twelve administrative or sub-cities, encompassing 22 kebeles (the smallest administrative units in Ethiopia. The city accommodates an estimated 53, 725 households and 395, 000 adults. Within Gondar, there is a referral hospital featuring a fistula treatment center, alongside eight governmental health centers and a general hospital. In the context of social diversity and equipped fistula treatment center, the study examined the complex community attitude towards obstetric fistula.

Source and study population

The source population for the study is comprised of adult individuals of males and females aged 18 years and older. The study population consisted of individuals aged 18 years and above who lives in the selected kebeles of the Gondar city for a minimum of six months.

Sample size determination

The sample size for the study was determined using the single population proportion formula, considering a 95% confidence level (Z-score of 1.96), a proportion of 50% (P), and a margin of error of 5% (W). This calculation yielded a requirement of 384 participants (N = (Z α/2)2 (P) (1-P) / W2 = (1.96)2 (0.5) (1–0.5) / (0.05)2). Factoring in a design effect of 1.5 and a 10% non-response rate adjustment (Adjusted sample size = Desired Sample size / (1-non-response Rate), the final sample size was determined to be 640 adults. Five kebeles (20% of the total) were randomly selected form the 22 kebeles using a lottery method. Study participants were selected proportionally based on the population size in each kebeles.

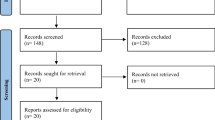

Sampling techniques and procedures

A multistage random sampling technique was employed in this study. Initially, five kebeles were randomly chosen out of the total 22 kebeles in the city, representing 20% of all kebeles (Fig. 1). Subsequently, households were selected through systematic random sampling with a sampling fraction of 3 (k = ni/Ni, where ni denotes the proportionally allocated sample from each selected kebele and Ni represents the total number of households in the respective kebele). The first household was selected through simple random sampling (ranging from 1 to 3), followed by the inclusion of every 3rd household in the research. Lastly, in households with more than one adult, a single individual aged 18 years or older was selected using the lotter method.

Study variables

Attitude towards obstetric fistula was the outcome variable, while socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, religion, marital status, educational status, occupation, family size, distance from health facility, and awareness of factors related to fistula were the independent variables for the study.

Measurement of variables

The outcome variable, attitudes towards obstetric fistula, was assessed using a Likert scale with 17 items consist of five levels of agreement (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree). The total attitude score was calculated and categorized as either favourable or unfavourable based31. The scores for an individual participant can range from 1 to 85 points. Each respondent’s score was then classified based on this overall total. Respondents were instructed to indicate their level of agreement on a scale of 1 to 5 for each statement, with 1 representing strong disagreement and 5 representing strong agreement. The sum of all ratings determined the final score for each respondent. Participants whose total scores exceeded the median (59.09 points) were classified as having a favourable attitude, while those scores below or equal to the median were categorized as having an unfavourable attitude. Internal consistency of the questionnaire was estimated using Cronbach`s alpha, and was found to be good (> 0.70). In addition to the outcome variable, the independent variables were measured as follows:

Heard of obstetric fistula was dichotomized as ‘yes’ = ever heard of obstetric fistula and ‘no’ = never heard of obstetric fistula. Heard of obstetric danger signs was dichotomized as ‘yes’ = heard of at least one of the 12 obstetric danger signs that contributes for obstetric fistula (adolescent pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, haemorrhage, prolonged labour, macrosomia, obstructed labour, uterine rupture, malpresentation of the foetus, mismanagement of labour, maternal sepsis, septic abortion, or home-birth-related injuries) and ‘no’ = never heard of any of these danger signs. Moreover, awareness about obstetric fistula was assessed using a structured questionnaire comprising twelve items. These items covered key aspects of obstetric fistula, including general information, causes, symptoms, prevention, treatment, long-term effects, burden, impact on quality of life, the role of obstructed labour in its development, effects on a woman’s social life, available programs addressing obstetric fistula, and the consequences of delayed treatment. Each ‘yes’ response was scored as 1 point, and ‘no’ responses were scored as 0. The total score was calculated for each respondent, and awareness was dichotomized based on the mean score: those scoring ≥ the mean was categorized as "aware," and those scoring < the mean were categorized as "not aware."

Data collection methods and procedures

A one-day training was given to data collectors about the purpose of the study, data collection tools, techniques, and ethical issues. Data were collected using face-to-face interviewer-administrated pretested structured questionnaire which were adapted through review of relevant literature. The data were collected via an open-source Kobo Toolbox. The data were subsequently exported to an excel spreadsheet for processing, version 2108 (Microsoft Corp), and imported to the R statistical software package for analysis.

Data quality assurance

The questionnaire was initially translated into the local language, Amharic, and then back-translated into English to verify consistency. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of the sample size (32 respondents). Training sessions were provided to the data collectors and supervisors on how to approach respondents and collect data. The investigators supervised the data collection process on daily bases to guarantee the consistency and completeness of data on a daily basis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented using absolute and relative frequencies, with the exact binomial confidence interval (CI) provided for the relative frequencies. Bi-variable logistic regression was conducted to gain insights into the determinants of the attitude towards obstetric fistula. Variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.2 in the bivariable logistic regression were chosen for inclusion in the multivariable logistic regression model. The results were reported as adjusted odds ratios. The data analysis was performed using the open-source statistical software R, version 4.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). A two-sided test was applied to all hypotheses with a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05), and the corresponding 95% CI was reported.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

In this study, a total of 640 individuals were involved. The total attitude score for each respondent ranged from 1 to 85 points, with a mean of 59.06 ± 5.68, and a median of 59.09 (IQR: 33–74). The median age of the participants were 32 years (IQR: 19–64). Almost half of the study participants (49.1%) were males, while 45.9% (n = 294) had attained a secondary level of education as their highest educational achievement. Majority of the study participants were married (68.8%, n = 440) and had a family size ranging from 3 to 5 members (61.9%, n = 396) (Table 1).

Awareness of obstetric fistula related characteristics

In this study, 369 (57.7%) individuals were not heard of obstetric fistula, and over half of the study participants did not hear of obstetric danger signs that could contribute for obstetric fistula and the associated complications. Out of the total 640 participants, only 59.8% (n = 383) demonstrated awareness concerning obstetric fistula, including its risk factors, preventive measures, and the availability of management strategies (Table 2).

Community`s attitude towards obstetric fistula

Three hundred and five respondents, representing 47.7% (95% CI: 43.7–51.6) of the total sample, exhibited favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula prevention, symptoms, risk factors, complications, and health-seeking behaviour. A significant proportion of participants believed that obstetric fistula is associated with the influence of evil spirits and can be inherited, with percentages of 45.2% (n = 138) and 68.5% (n = 209), respectively. Furthermore, over two-thirds of the participants with favourable attitude perceived that obstetric fistula could be prevented by delivering with the assistance of trained healthcare professionals, with a percentage of 77.7% (n = 237) (Table 3).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis

Both the bivariable logistic regression analysis and the multivariable logistic regression analysis, after adjusting the effect of covariates, showed that Age of the participants, female gender, attending primary education, and aware about obstetric factors were all statistically significant independent factors influencing the community attitude towards obstetric fistula.

The odds of having a favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula is 3.9 times higher (95% CI: 1.8–8.5) among individuals aged 20–35 compared to those aged 51 or older. Similarly, individuals in the 36–50 age group are 6.36 times more likely to have a favourable attitude compared to those aged 51 or older. Additionally, the likelihood of having a positive attitude towards obstetric fistula is 1.5 times higher (95% CI: 1.1–2.2) among females compared to males.

The likelihood of possessing a positive attitude towards obstetric fistula is 1.86 times higher among individuals with primary education compared to those who have completed secondary education. Moreover, the odds of harbouring a positive attitude are 3.04 times higher (95% CI: 2.0–4.6) among individuals with good awareness of obstetric fistula compared to those with no awareness. These findings are detailed in Table 4.

Discussion

This study examined the attitudes towards obstetric fistula within the communities of Gondar town, Ethiopia. Furthermore, the study identified the factors that influences the communities’ attitudes towards obstetric fistula.

In this study, it was found that 47.8% of community members in Gondar town have a favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula. A similar study from Nepal32 among married women identified that 50.0% of them had positive attitude towards obstetric fistula. This may indicate a concerning lack of awareness and support for individuals affected by this debilitating condition.

One possible justification for the finding that nearly 50% of community members have a favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula could be a lack of comprehensive education and awareness campaigns about this condition. Cultural beliefs, social stigma, and limited access to information and healthcare services may also contribute to these attitudes33,34.

In this study, 68.5% of participants believed that obstetric fistula is heritable, while 45.2% associated the condition with evil spirits. These misconceptions surrounding obstetric fistula can lead to stigma and discrimination against women who suffer from the condition. It is important to educate the public about the true causes of obstetric fistula, which are primarily related to lack of access to proper maternal healthcare22. By dispelling myths and increasing awareness, it is recommended to work towards eradicating obstetric fistula and improving the lives of affected women. On the contrary, a study conducted in Ibadan, Nigeria35, among healthcare workers demonstrated that 91.2% of them had positive attitude towards obstetric fistula. This proportion is much higher than the current study which might be due differences in socio demographic characteristics of the study participants. While 45.9% of the study participants had attained a secondary level of education as their highest educational achievement in the current study, all were with higher level of education in the report from Nigeria who were also expected to have adequate awareness about obstetric fistula. In the current study; however, 57.7% of the study participants were not aware of obstetric fistula, and half of them had inadequate awareness about obstetrics danger signs that contributes to obstetric fistula and its associated complications. This finding is in line with the study conducted in Egypt36, Ethiopia28,37, and Burkina Faso38, but better than a finding from Gambia27. This may be attributed to several factors. Limited access to educational resources, cultural stigmas surrounding reproductive health issues39, and a lack of targeted public health campaigns can contribute to such low awareness levels40,41. Obstetric fistula, often resulting from prolonged labour without timely medical intervention, is a condition that can be shrouded in taboo, leading to reduced discussion and understanding among affected populations39. Additionally, healthcare infrastructure and the availability of trained professionals42 can significantly influence awareness and education regarding this condition. In contrast, the study in Uganda43, reported that 45% of communication professionals exhibited satisfactory awareness of obstetric fistula. This relatively higher percentage might reflect better access to information and training among communication professionals, who are often engaged with public health messaging and community outreach. This implies the need to design community tailored awareness creation campaigns to bring positive attitude within the community in the study setting.

Younger community members, under the age of 20, exhibited a significantly more positive attitude towards obstetric fistula compared to their older counterparts. The odds ratio was 7.7, with a 95% confidence interval of 2.3–28 indicating a strong association between younger age and attitude towards obstetric fistula. The odds of having favourable attitude toward s obstetric fistula is nearly 8 times higher in individuals under the age twenty compared to those above fifty years. The observed disparity in awareness of obstetric fistula may be attributed to an awareness gap between younger and older individuals. A study from Ethiopian National Demographic Survey reported that individuals aged 20–25 years were 17% more likely to be aware of obstetric fistula compared to those older than 25 years28. This finding suggests that younger individuals may have greater access to information, potentially facilitated by social media platforms28. Implementing targeted awareness campaigns could play a pivotal role in addressing this disparity and improving awareness among older age groups. However, the wide confidence interval suggests some uncertainty in the estimate because the smaller sample size in this age group (20 participants). Future studies with larger sample sizes are essential to strengthen the evidence base and guide effective public health strategies. Similarly, individuals in the age range 20–35, and 36–50 were more likely to have nearly four times (AOR: 3.9; 95%CI: 1.8–8.5) and seven times (AOR: 6.36; 95% CI: 3.0–14.1) favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula compared to those over 50 years. This may be due to the fact that the younger population is more likely to have access to information related to obstetric fistula which may contributed for their positive attitude towards the condition.

Women are more likely to have a positive attitude towards obstetric fistula compared to men, with women being 1.5 times more likely to have a favourable attitude towards this condition. A study from Egypt reported a highly substantially positive association among overall awareness and attitude towards obstetric fistula7. This positive outlook among women may be attributed to their understanding of the physical and emotional impact it can have on affected individuals. Women’s positive attitude towards obstetric fistula may stem from their understanding of the physical and emotional toll it can take on women44,45. They may also be more empathetic towards the challenges faced by those affected by this condition46. On the other hand, men may not have the same level of awareness or personal connection to the issue, resulting in a less positive attitude overall. Narrowing this difference is important to minimize gender disparities in attitudes towards obstetric fistula and promote greater support and understanding across all genders.

Individuals with only a primary education are 1.86 times more likely to have a favourable attitude compared to those who have completed secondary education, according to a study with a 95% confidence interval of 1.3–2. However, it is important to note that education level is just one factor that can influence attitudes. Other variables such as socioeconomic status, cultural background, and personal experiences may also play a significant role in shaping an individual’s perspective47. Additionally, attitudes are complex and can be influenced by a variety of factors, making it essential to consider a holistic approach when studying attitudes and behaviours48. Another possible justification for individuals with primary education being more likely to have a favorable attitude towards obstetric fistula compared to those who completed secondary education could be related to the level of exposure and understanding of the issue. Individuals with primary education may have received basic information about obstetric fistula, which could lead to a more empathetic and supportive attitude. On the other hand, those who completed secondary education may have higher expectations or be more critical due to their advanced level of education, potentially leading to a less favorable attitude.

People with good awareness of obstetric fistula (AOR: 3.04; 95% CI: 2.0–4.6) were more likely to have favourable attitude towards obstetric fistula compared those without awareness. One possible justification for people with good awareness of obstetric fistula being more likely to have a favourable attitude compared to those without awareness could be the direct correlation between knowledge and empathy27,28. Individuals who are well-informed about obstetric fistula are more likely to understand the physical and emotional toll it takes on women. This deeper understanding can lead to increased empathy and support for those affected by the condition, resulting in a more positive attitude. Conversely, individuals without awareness may lack the necessary information to comprehend the impact of obstetric fistula, leading to a less favourable attitude due to ignorance or misunderstanding32.

The study provides a detailed examination of attitudes towards obstetric fistula within the communities in both genders, and identifies factors that influence these attitudes. By considering age, gender, education level, and awareness of the condition, the study offers a comprehensive analysis of the topic. The study highlights common misconceptions surrounding obstetric fistula, such as beliefs that it is heritable or associated with evil spirits. By identifying and addressing these misconceptions, the study emphasizes the importance of education and awareness in changing attitudes towards the condition. However, the findings from the study should be interpreted in line with some limitations. The study focuses on attitudes towards obstetric fistula in a specific community in Gondar town, Ethiopia. The findings may not be generalizable to other populations or regions with different socio-demographic characteristics, cultural beliefs, or healthcare systems. The study relies on self-reported data from participants, which may be subject to bias. Participants may provide socially desirable responses or inaccurately report their attitudes towards obstetric fistula, leading to potential measurement errors. The study provides a snapshot of attitudes towards obstetric fistula at a single point in time. Longitudinal data tracking changes in attitudes over time would have provided a more comprehensive understanding of how attitudes evolve and the effectiveness of interventions. While the study identifies age, gender, education level, and awareness as factors influencing attitudes towards obstetric fistula, other potential variables such as socio-economic status, cultural norms, and personal experiences were not fully explored. A more comprehensive assessment of these factors could provide a more nuanced understanding of attitudes. Potential confounding variables such as cultural beliefs and personal experiences were not included in in the analysis which could impact the interpretation of the results. Furthermore, from a theoretical perspective, the forced dichotomization of attitude into favourable and unfavourable categories excludes the neutral stance, which may overlook a significant portion of the population. However, from a practical standpoint, it is essential to provide interventions for individuals in the neutral position. This approach can empower them to make informed choices, either leaning toward a favourable or unfavourable attitude. By addressing this neutral group, we can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding and engagement with the issue at hand, ultimately promoting better health outcomes.

Conclusions

The study shows a significant difference in attitudes towards obstetric fistula based on age, gender, education level, and awareness of the condition. Younger individuals, women, those with primary education, and those with good awareness of obstetric fistula were more likely to have a positive attitude towards the condition. This emphasizes the importance of tailored awareness campaigns and educational initiatives to promote understanding and support for individuals affected by obstetric fistula in the community.

Recommendations

Develop educational initiatives specifically designed to raise awareness about obstetric fistula among different age groups, genders, and educational backgrounds in the community. Tailoring the information to suit the specific needs and preferences of each group can help increase understanding and support for individuals affected by obstetric fistula. Given that younger community members exhibited a more positive attitude towards obstetric fistula, it is important to involve youth in awareness campaigns and educational programs. Younger individuals can serve as advocates for change and help spread accurate information about obstetric fistula within their communities. Since women were more likely to have a positive attitude towards obstetric fistula, efforts should be made to empower women to take on leadership roles in promoting awareness and support for individuals affected by the condition. Providing women with the necessary resources and platforms to advocate for change can help bridge the gender gap in attitudes towards obstetric fistula. It is essential to maintain ongoing awareness campaigns and advocacy efforts to ensure sustained support for individuals affected by obstetric fistula. Collaborating with local organizations, healthcare providers, and community leaders can help create a network of support and resources for those in need. We recommend that future studies should explore additional categories or continuous measures of attitude to capture the full spectrum of community`s perceptions towards obstetric fistula.

Data availability

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OF:

-

Obstetric fistula

- UNFPA:

-

United Nations population fund agency

- VVF:

-

Vesico vaginal fistula

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Lozo, S., Morgan, M.A., Polan, M.L., Sleemi, A. & Bedane, M.M. Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition. 95 (2015).

Sanni OF, Dada MO, Ariyo AO, Salami AO, Afelumo OL, Ayosanmi OS, et al. The prevalence and management of obstetric fistula among women of reproductive age in a low-resource setting. Healthc. Low-resource Setti. 11(1) (2023).

HARMS WC. OBSTETRIC FISTULA. UNFPA (2012)

Changole, J., Thorsen, V. C. & Kafulafula, U. “I am a person but I am not a person”: Experiences of women living with obstetric fistula in the central region of Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 1–13 (2017).

Meurice, M., Genadry, R., Heimer, C., Ruffer, G. & Kafunjo, B. J. Social experiences of women with obstetric fistula seeking treatment in Kampala, Uganda. Ann. Global Health. 83(3–4), 541–549 (2017).

Hilton, P. Urogenital Fistula: Studies on Epidemiology and Treatment Outcomes in High-Income and Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Newcastle University (2019)

Wall, L. L. Overcoming phase 1 delays: The critical component of obstetric fistula prevention programs in resource-poor countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12, 1–13 (2012).

Baker, Z., Bellows, B., Bach, R. & Warren, C. Barriers to obstetric fistula treatment in low-income countries: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 22(8), 938–959 (2017).

Bashah, D. T., Worku, A. G., Yitayal, M. & Azale, T. The loss of dignity: Social experience and coping of women with obstetric fistula, in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 19, 1–10 (2019).

Hurissa, B. F., Koricha, Z. B. & Dadi, L. S. Challenges and coping mechanisms among women living with unrepaired obstetric fistula in Ethiopia: A phenomenological study. PLoS ONE 17(9), e0275318 (2022).

Tebeu, P. et al. Knowledge, attitude and perception about obstetric fistula by Cameroonian women. Progres en Urologie: Journal de L’association Francaise D’urologie et de la Societe Francaise D’urologie. 18(6), 379–389 (2008).

Tebeu, P.M., Rochat, C.-H., Kasia, J.M. & Delvaux, T. Perception and attitude of obstetric fistula patients about their condition: A report from the Regional Hospital Maroua, Cameroon (2010)

Ninsiima, L. R., Chiumia, I. K. & Ndejjo, R. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Reprod. Health. 18, 1–17 (2021).

Lyimo, M. A. & Mosha, I. H. Reasons for delay in seeking treatment among women with obstetric fistula in Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 19, 1–8 (2019).

Nduka, I. R., Ali, N., Kabasinguzi, I. & Abdy, D. The psycho-social impact of obstetric fistula and available support for women residing in Nigeria: A systematic review. BMC Women’s Health. 23(1), 87 (2023).

Gulati, B., Unisa, S., Pandey, A., Sahu, D. & Ganguly, S. Correlates of occurrence of obstetric fistula among women in selected States of India: An analysis of DLHS-3 data. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn. 3(2), 121 (2011).

Whitcomb, K. Obstetric Fistulas in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 1(4), 193–197 (2008).

Umoiyoho, A. & Inyang-Etoh, E. Community misconception about the aetiopathogenesis and treatment of vesicovaginal fistula in Northern Nigeria. Int. J. Med. Biomed. Res. 1(3), 193–198 (2012).

Wegner, M., Ruminjo, J., Sinclair, E., Pesso, L. & Mehta, M. Improving community knowledge of obstetric fistula prevention and treatment. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 99, S108–S111 (2007).

Rundasa, D. N., Wolde, T. F., Ayana, K. B. & Worke, A. F. Awareness of obstetric fistula and associated factors among women in reproductive age group attending public hospitals in southwest Ethiopia, 2021. Reproduct. Health. 18, 1–7 (2021).

Kalembo, F. & Zgambo, M. Obstetric fistula: A hidden public health problem in Sub-Saharan Africa. Arts Soc. Sci. J. (2012).

Lufumpa, E., Doos, L. & Lindenmeyer, A. Barriers and facilitators to preventive interventions for the development of obstetric fistulas among women in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 18, 1–9 (2018).

Atuhaire, S., Mugisha, J.F., Odukogbe, A.-T.A., & Ojengbede, O.A. Association of socio-demographic and obstetric factors with obstetric fistula patients’ perceptions towards life fulfilment in Kitovu Hospital, Uganda (2020)

Lucy, I. et al. Assessment of the knowledge and obstetric features of women affected By Obstetric Fistula at Obstetric Fistula Centre in Bingham University Teaching Hospital, Jos Nigeria. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 1(1), 1–9 (2020).

Pollaczek, L., El Ayadi, A. M. & Mohamed, H. C. Building a country-wide Fistula Treatment Network in Kenya: Results from the first six years (2014–2020). BMC Health Serv. Res. 22(1), 280 (2022).

Kasamba, N., Kaye, D. K. & Mbalinda, S. N. Community awareness about risk factors, presentation and prevention and obstetric fistula in Nabitovu village, Iganga district Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 13, 1–10 (2013).

Tweneboah, R., Budu, E., Asiam, P. D., Aguadze, S. & Acheampong, F. Awareness of obstetric fistula and its associated factors among reproductive-aged women: Demographic and health survey data from Gambia. Plos One. 18(4), e0283666 (2023).

Aleminew, W., Mulat, B. & Shitu, K. Awareness of obstetric fistula and its associated factors among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 11(12), e053221 (2021).

Molzan Turan, J., Johnson, K. & Lake, P. M. Experiences of women seeking medical care for obstetric fistula in Eritrea: Implications for prevention, treatment, and social reintegration. Global Public Health. 2(1), 64–77 (2007).

Odhiambo A. I am not dead, but i am not living: Barriers to fistula prevention and treatment in Kenya (2010).

B.S. B. Learning for Mastery. Instruction and Curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, Topical Papers and Reprints Evaluation Comment. Number 1(1):1(2):n (1968).

Dahal, B. D. & Shakya, J. Awareness and attitude regarding obstetric fistula among married women. J. Chitwan Med. Coll. 10(3), https://doi.org/10.54530/jcmc.103 (2020).

Kimani, Z. M. The Effects of Obstetric Fistula, Impact and Coping Strategies of Women in Kaptembwa-Nakuru (Egerton University, 2014).

Gatwiri, K. & Gatwiri, K. Rationalising fistulas: A cultural influence and response. African womanhood and incontinent bodies: Kenyan Women with Vaginal Fistulas. 125–55 (2019)

Olukemi Bello, O. & Lawal, O. O. Healthcare workers knowledge and attitude towards prevention of obstetric Fistula. Int. J. Res. Rep. Gynaecol. 1(1), 25–33 (2018).

Kamel, F. R., Ramadan, S., Elbana, H. & Kamal, F. Pregnant womens knowledge and attitude regarding obstetric fistula. Benha J. Appl. Sci. 8(4), 257–267 (2023).

Addimasu, B., Nigatu, D., Yadita, Z. S. & Melkie, M. Awareness on obstetric fistula and associated factors among women health development army, in the South Gondar zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 7(10), e70141 (2024).

Banke-Thomas, A. O., Kouraogo, S. F., Siribie, A., Taddese, H. B. & Mueller, J. E. Knowledge of obstetric fistula prevention amongst young women in urban and rural Burkina Faso: A cross-sectional study. PloS One. 8(12), e85921 (2013).

Tohit, N. F. M. & Haque, M. Forbidden conversations: A comprehensive exploration of taboos in sexual and reproductive health. Cureus. 16(8), e66723 (2024).

Banke-Thomas, A. O., Wilton-Waddell, O. E., Kouraogo, S. F. & Mueller, J. E. Current evidence supporting obstetric fistula prevention strategies in sub Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the literature. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 18(3), 118–127 (2014).

Ramsey, K., Iliyasu, Z. & Idoko, L. Fistula Fortnight: innovative partnership brings mass treatment and public awareness towards ending obstetric fistula. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 99, S130–S136 (2007).

Keri, L., Kaye, D. & Sibylle, K. Referral practices and perceived barriers to timely obstetric care among Ugandan traditional birth attendants (TBA). Afr. Health Sci. 10(1), 75 (2010).

Tseunwo, C., Mail, S.H.W., Antaon, J.S.S., Obama, C.M., Tebeu, P.M. & Rochat, C.H. Obstetric fistula knowledge, attitudes and practices among the professionals of communication in Yaounde. Health Sci. Dis. 2020;21(6)

Tafesse, B., Muleta, M., Michael, A. W. & Aytenfesu, H. Obstetric fistula and its physical, social and psychological dimension: The Etiopian scenario. Acta Urol. 23, 25–31 (2006).

Gebresilase, Y.T. A qualitative study of the experience of obstetric fistula survivors in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Women’s Health. 6, 1033–43 (2014).

Kabayambi, J. et al. Living with obstetric fistula: Perceived causes, challenges and coping strategies among women attending the fistula clinic at Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health. 4(3), 352–361 (2014).

Khisa, W., Wakasiaka, S., McGowan, L., Campbell, M. & Lavender, T. Understanding the lived experience of women before and after fistula repair: A qualitative study in Kenya. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 124(3), 503–510 (2017).

Fabrigar, L. R., Petty, R. E., Smith, S. M. & Crites, S. L. Jr. Understanding knowledge effects on attitude-behavior consistency: The role of relevance, complexity, and amount of knowledge. J. Personal Soc. Psychol. 90(4), 556 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to acknowledge the maternal health project coordinating office at the University of Gondar, sponsored by the United Nations Population Fund Agency, for its financial support to conduct the study. Moreover, we would like to thank all data collectors and supervisors.

Funding

The data collection costs were partially funded by the maternal health project coordinating office at the University of Gondar, sponsored by the United Nations Population Fund Agency, VP/S/10291.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AL, DSA, and WFC: Conceived and designed the study, substantially contributed in methodology of the article, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the original draft of the manuscript, revised, and approved the final manuscript. AB, ADT, BL, CB, and TAA: Involved in the data management, analysis and interpretation of the findings. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no financial and non-financial competing interests. The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical standard of the University of Gondar (VP/S/10291) and compliance with local legislation and institutional guidelines. The participants provided verbal and informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chanie, W.F., Berhe, A., Tilahun, A.D. et al. Community perceptions and determinants of obstetric fistula across gender lines. Sci Rep 15, 4514 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87192-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87192-4