Abstract

Tropical peatlands are carbon-dense ecosystems that are significant sources of atmospheric methane (CH4). Recent work has demonstrated the importance of trees as an emission pathway for CH4 from the peat to the atmosphere. However, there remain questions over the processes of CH4 production in these systems and how they relate to substrate supply. Principally, these questions relate to the relative contribution of recent photosynthetically fixed carbon, released as root exudates, versus carbon substrate supply from the slowly decomposing peat matrix to CH4 emissions within these ecosystems. Here, we examined the role of root inputs in regulating CH4 production inferred from soil emissions using a combination of in situ tree girdling, in situ13C natural abundance labelling via stem injections, and a 13CO2 labelling of transplanted plants of two contrasting plant functional types, a broadleaved evergreen tree, and a canopy palm. Girdling of broadleaved evergreen trees reduced CH4 fluxes by up to 67%. Stem injections of trees and palms with a natural abundance label resulted in significant isotopic enrichment of CH4 fluxes, reinforcing the link between root carbon inputs and peat CH4 fluxes. Ex situ13CO2 labelling of plants resulted in significant 13C enrichment of peat CH4 fluxes. Taken together, our results demonstrate for the first time that plant root exudates make a substantial contribution to CH4 production in tropical peatlands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical peatlands are a globally important carbon stock, are a significant contributor to global wetland methane (CH4) emissions, and highly vulnerable to climate change1,2,3,4. The net balance of CH4 fluxes from tropical peatlands is controlled by the water table position, with waterlogged anoxic conditions a prerequisite for methanogenesis, while methanotrophy dominates under drier aerobic conditions. Vegetation is also a key regulator of emissions, determining initial peat properties5, providing a regular litter supply6, as well as a mechanism of gas transportation7. However, the regulatory role of roots, which can release significant quantities labile carbon8,9 and oxygen10 at depth, is still unclear.

Significant diurnal variation in CO2 fluxes from tropical peatlands in Indonesia and Panama have previously been reported, with fluxes increasing rapidly throughout daylight hours and declining overnight11,12. Positive correlations have been found between diurnal changes in CO2 efflux and air temperature, possibly due to changes in decomposition of organic matter11, but also with rates of photosynthesis13 indicating the important contribution of root exudates to the labile peat carbon pool, and microbial respiration8,9. Similarly, there is evidence for diurnal variation in CH4 fluxes driven by changing rates of photosynthesis in wetland plants14,15,16. The link between CO2 and CH4 fluxes and recent photosynthetically fixed carbon is likely to be species specific through a combination of differences in root exudate profiles17, oxygen inputs10, rooting structures12, and contrasts in microbial community abundance and function18,19. Moreover, trees are also known to be an important pathway for CH4 transport, accounting for between one and two thirds of ecosystem fluxes7,20.

Techniques developed for partitioning the drivers of soil CO2 dynamics, for example trenching, severing roots mechanically, girdling (the removal of bark around the stem to reduce the flow of photoassimilates to the roots and mycorrhizae), and stable isotope labelling with 13C enriched and natural abundance isotopes21 also can be applied for interpreting CH4 dynamics40. Stable isotope labelling has been widely used to assess the contribution of recent photosynthetically fixed carbon to net CO2 fluxes in a range of systems including agriculture and plantation crop systems22,23, forests24,25, grasslands26,27, temperate peatlands28,29, and rice paddy fields15,30. Transfer of carbon to soil microbial communities can occur within hours but is dependent on plant species and size25,31,32. While many studies introduce a 13CO2 label in the gaseous phase for photoassimilation, stem injection of a label negates the challenges of labelling full sized trees in situ32. In addition, stable isotope labelling, particularly using highly enriched labels, can have significant associated costs making it often a prohibitively expensive way to demonstrate carbon flow pathways at scale. In contrast, natural abundance labelling, in exploiting differences in isotope ratios between sugars produced by C3 and C4 plant metabolism offers a cost-effective approach for labelling in situ.

Stable isotope labelling also allows assessment of key microbial groups driving the use of recent photoassimilates relative to older organic carbon. Within organic grassland soils and boreal peats, fungal biomarkers have frequently been shown to be rapidly enriched following labelling, with a decreasing 13C enrichment over time, indicating the ability of fungi to rapidly incorporate plant derived carbon22,26,33. Significant enrichment over short timescales following labelling has also been demonstrated for Gram negative bacteria in agricultural soils34, and peats22. Rhizosphere soils have also been found to have greater abundance of Gram negative bacteria than bulk soils implying a further possible role in decomposition of labile carbon derived from recent plant inputs35,36. In the longer term, enrichment of Gram positive bacteria suggests an important role in the degradation of more recalcitrant organic matter22,37. Contrasts in the relative incorporation between PLFA groups between different plant communities would therefore likely indicate functional differences in the microbial communities under contrasting peat types.

In this study, we examined the role of trees in the CH4 production process. assess the role of root inputs of carbon using three methods: (i) in situ girdling of tree stems; (ii) in situ stem injection of a natural abundance label; (iii) ex situ13CO2 labelling of plants. We hypothesised: (i) girdling would significantly reduce peat surface CH4 fluxes due to reduced root inputs; (ii) stem injections of a natural abundance label and 13CO2 labelling would significantly enrich CH4 fluxes following labelling; (iii) CH4 enrichment of peat surface emissions following labelling will differ between plant species.

Methods

Field site, vegetation and peat properties

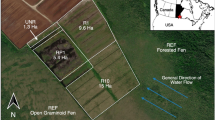

To quantify the role of roots and root inputs of carbon in driving tropical peatland CH4 dynamics, we integrated an in situ girdling (conducted in September–October 2013), a natural abundance labelling (conducted February 2015) and an ex situ13CO2 pulse-labelling pot experiment (February–May 2016). All studies were conducted at the San San Pond Sak freshwater and marine wetland located in Bocas del Toro province, Panama, under ANAM research/collection permits SE/P-29-13 and SE/P-34-13. The wetland features an 80 km2, 8 m deep ombrotrophic peatland at Changuinola initiated 4,000–5,000 years ago38. Coastal vegetation is dominated by Rhizophora mangle, followed by Raphia taedigera palms, mixed species forest stands, Campnosperma panamensis broadleaved evergreen tree stands and Myrica-Cyrilla bog-plain. Accompanying the succession of plant communities is a strong decline in nutrient availability towards the interior of the wetland39, alongside similar gradients in organic matter properties5 and microbial community structure40.

Between 2002 and 2016 mean annual air temperature was 25.7 °C, with little intra-annual variability. During the period of sampling mean temperature was 26.9 °C. Over the same period, mean annual rainfall was 3,293 mm, with a mean of 173 mm in February to May 2016. Mean sub-surface peat temperature is 25.0 °C. At the study sites, the water table fluctuates from just above to just below the peat surface, with a range of approximately 20 cm41.

Tree girdling

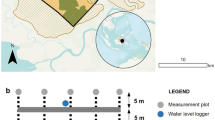

To determine the role of transfer of recently photosynthesied carbohydrates released in to the rhizosphere for CH4 emissions from the peat surface we carried out a girdling experiment in September 2013. Girdling involved removal of the bark, xylem and phloem tissue around the tree trunk to stop transfer of carbohydrates to areas below the point of girdling (Hogberg et al., 2002). We carried out a girdling experiment in September to October 2013 in a monodominant C. panamensis stand within the San San Pond Sak peatland. Paired C. panamensis trees (n = 8) were randomly allocated a treatment (control or girdled). Diameter at breast height ranged between 50 and 150 cm with a mean diameter of 85 cm. Girdling was carried out beginning of October by removing 2–3 cm of tissue around the entire tree.

Soil CH4 flux was monitored before, immediately after and then again after two weeks at the same point, measured 1 m from the trunk of each tree in a randomly selected direction, to account for the previously reported spatial heterogeneity in rooting zone CH4 dynamics40. The mean water table depth across the site was 0.75 cm above the surface of the peat at the time of sampling, in keeping with the previously reported range of values for the site41.

For measuring CH4 fluxes, we inserted a lightweight polypropylene (PP) rim (inner diameter: 30 cm; height: 15 cm) 10 cm deep into the peat surface, the day prior to measurement. For the measurment, we then slotted a cylindrical chamber (diameter 30 cm, height 20 cm) into the the rim ensuring an air-tight seal. To reduce disturbance of the soil surface a 120 × 50 cm polystyrene board was used to kneel on during sampling. It is plausible that accessing the sampling locations resulted in ebullition. The chambers were connected to an Ultra-Portable Greenhouse Gas Analyser (UGGA, Los Gatos Research Inc., Mountain View, USA) via two 4.6 m long and 5 mm inside diameter polytetrafluoroethylene coated polyvinyl chloride parallel tubes (Nalgene, Rochester, USA) set in a continuous flow mode operating as a closed loop with a flow of 2–4 L min−1. The UGGA measured CH4 with the Off-Axis Integrated Cavity Output Spectroscopy (OA-ICOS) at a frequency of 0.33 Hz. Gas concentrations were then measured for 5 min. The analyser’s uncertainty in the range of 0.01 ppmv to 100 ppmv of methane is < 1% without calibration and the precision is ± 0.6 ppb over a period of 100 s.

The rates were calculated from linear regressions made between the concentration changes starting after an equillibration period of 90 s and the elapsed runtime. After accounting for the chamber volume, which varied between measurements depending on the requiered chamber size (the range of chamber size was 0.28 to 1.49 dm3 and 95 to 715 cm2 for the volume and the area, respectively), rates were then expressed relative to the exchange surface area. All flux series was inspected to ensure ebullition was not affecting the calculated fluxes.

The ambient fluxes were corrected to reference fluxes using the following transformation:

where Fref = flux corrected to reference conditions, Famb = flux measured at ambient conditions, Pamb = atmospheric pressure at ambient conditions, Pref = pressure at reference conditions (1 atm), Tref = temperature at reference conditions (298 K), Tamb = temperature at ambient conditions in K. During subsequent data analysis, three pairs with negative CH4 fluxes i.e. CH4 was oxidised, were discounted as CH4 oxidation would mask the contribution of roots exudates to fluxes10.

Natural abundance labelling

Six C. panamensis trees and six R. taedigera palms were selected for stem injection of a C4 derived sugar based on similar heights and diameter-at-breast-height (DBH). A 2 cm hole was drilled at a 45° angle into trees at approximately 30 cm above the peat surface. A 30 cm section of rubber tubing was silicon sealed in place using a non-emitting sealant. Three trees of each species were randomly selected for labelling. For each plant, 100 g of C4 derived sugar (− 12.11 ± 0.009) was dissolved in 2 L of deionised water and connected to the tubing through a hole in the lid. The bottle was subsequently inverted to allow the flow of the solution into the stem. Unlabelled controls received 2 L of deionised water. Peat surface CH4 fluxes were subsequently measured using the closed chamber technique as above, but with duplicate samples collected after 20 min for 13C analysis. Fluxes were measured immediately prior to labelling and 1, 4, 5 and 7 days following labelling. At the conclusion of the study, bottles from which only a limited volume of water had been lost (one labelled and one control C. panamensis trees, and one labelled and two control R. taedigera palms) were discounted from subsequent analysis. Due to a lack of statistical replication for R. taedigera palms, data from individuals of both species was combined (n = 4 for treatment; n = 3 for control).

13CO2 pulse labelling assay

Plant species were selected based on their high relative abundances within the forest stands at Changuinola. Peats derived from C. panamensis and R. taedigera have previously been shown to differ significantly in terms of in situ GHG production and organic matter properties5,42 and microbial community structure43. In addition to C. panamensis and R. taedigera, which form monodominant forest stands, Symphonia globulifera, a second broadleaved evergreen tree was also selected for labelling. During transplantation, there was high mortality of C. panamensis saplings, necessitating the selection of an additional plant species. S. globulifera has a tall trunk supported by buttress roots, with lenticels for root oxygenation giving it a similar physiology to C. panamensis which also has lenticels.

Nine R. taedigera, C. panamensis and S. globulifera, selected based on similar height (30–40 cm) and diameter-at-breast-height (DBH, 0.3–0.4 cm), were collected from the mixed forest stand. Peat around the plants was removed to a 25 cm depth and in a 20 cm radius around plant stems to ensure removal of the intact root system. Plants were placed in pots and transferred to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute research station on Isla Colón. Plants were maintained at the research station for three months prior to the beginning of labelling, including regularly watering to maintain the water table at 1 cm above the peat surface, and placing in partial shade to mimic in situ conditions.

Labelling was conducted using custom made Perspex chambers (15.71 L) fitted with a suba seal for labelling and sampling and with a battery powered fan (Evercool EC4010M12EA) powered by 9 V batteries to ensure mixing of headspace gases. Labelling was conducted between 9 am and 5 pm in direct sunlight to maximise plant photosynthesis rates. Six plants from each species were randomly selected for labelling, with three of each species retained as unlabelled natural abundance controls. The Perspex chamber was placed over the selected saplings and gently pushed into the peat to ensure a tight fit. Plants were labelled with 13CO2 (99 atom % 13C; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) added in pulses of 100 mL. Chambers remained in place for 40 min to allow prolonged uptake of the label before lifting to allow the plants cool and condensation to dissipate. This time was chosen, as during trials, temperatures in the headspaces gradually rose over time, in some instances reaching over 40 °C. Labelling was repeated for a total of five pulses during the course of the day, beginning on 18th May 2016. This approach does incur the risk of directly labelling the methanogenic communities, thereby driving hydrogentrophic methanogenesis. However, the elevated water tables used in our experiment will have acted in part as a barrier to diffusion for atmospheric CO2, as they do for oxygen, thereby resulting in the anoxic conditions beneath the peat surface that are required for methanogenesis. Our previous work shows relatively high dissolved oxygen in surface waters that will result in the dominance of methanotrophy10.

Smaller headspaces (0.37 L) were used for sampling air directly from the peat surface for later CH4 and 13CH4 analysis. Duplicate headspace samples were collected one day prior to labelling, and one, three, seven and 14 days post labelling. Samples (20 mL) were collected immediately following the fitting of the headspace and after 10 and 20 min, and injected into 12 mL pre-evacuated glass exetainers fitted with a screw cap septum.

At the conclusion of the pot experiment four C. panamensis, four S. globulifera plants and one R. taedigera palm were dead and samples collected from these pots were excluded from further analysis. However, it is unclear if the high mortality was driven by treatment as there was high plant loss during transplantation from the site. Samples from C. panamensis and S. globulifera were thus combined due to their broadly similar physiologies to assess the response of broadleaved evergreen trees for the purposes of statistical analysis. Both species feature similar rooting structures and were of similar height, DBH and biomass with no significant differences in associated peat properties. This combination of three species is subsequently referred to as plant type, on the basis of the different physiologies and morphologies between broadleaved evergreen trees (C. panamensis and S. globulifera), and the palm (R. taedigera).

CH4 and 13CH4 isotopic analyses

CH4 concentrations were quantified using gas chromatography (GC) using a single injection system fitted with a 1 mL sample loop, using H2 as a carrier gas and a non-polar methyl silicone capillary column (GC-2014; Shimadzu, Milton Keynes, UK). CH4 was detected using a flame ionization detector. Samples that were under-pressurised at the time of analysis were discarded; these duplicate samples were not subsequently analysed by GC-C-IRMS.

For determination of δ13C-CH4, headspace gases were manually injected into an Isoprime Trace gas analyser, which was coupled to an Isoprime continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Elementar UK, Stockport). Samples were initially passed through a Magnesium perchlorate/ Carbosorb scrubber trap at a flow rate of 20 mL min−1 to remove water and CO2. CH4 was then oxidised in a combustion furnace using a braided platinum/copper/nichrome furnace wire inside a ceramic furnace tube (200 mm × 0.4 mm i.d.) heated in a furnace to 960 °C. A preparation flow rate of 10 psi was required to give a flow rate of 20 mL min−1 through the furnace at full operating temperature. Calbiration was achieved using CH4 standards cross calibrated with a CO2 reference gas, calibrated against NIST REF-Heavy Palaeomarine Origin (CO2) (RM 8562) and NIST REF-Biogenic Modern Biomass Origin (CO2) (RM 8564). δ13C-CH4 was expressed in per mil (‰). The reproducibility of δ13C-CH4 was better than ± 0.2‰.

PLFA and 13 C-PLFA analysis

PLFAs were extracted from peat collected 14 days following labelling following the Bligh and Dyer protocol (1959). Total lipids were extracted from 500 mg of freeze-dried peats using a citrate buffer (0.15 M, pH 4), 1.9 mL chloroform (CHCl3), 3.8 mL methanol (MeOH), and 2 mL of Bligh and Dyer reagent (prepared at a 1: 2: 0.8 volume ratio of CHCl3: MeOH: citrate buffer). Extracts were subsequently vortexed for one minute and left at room temperature to separate over two hours before centrifugation for 10 min at 650 RCF. The supernatant was subsequently transferred to a CHCl3 rinsed glass tube. This step was repeated to ensure complete extraction of lipids from the peat pellet. Citrate buffer and chloroform (mixed at a 1:1 volume ratio) were left overnight to separate aqueous and organic phases. The layer of chloroform was transferred to a clean glass tube and blown dry under a stream of compressed N2 at room temperature24.

Lipids were separated using a silica solid phase extraction cartridge which was which was rinsed first with 15 mL methanol and 2.5 mL chloroform. The dry lipid extract was re-suspended in 0.5 mL chloroform and added to the column. Lipids were separated into neutral lipids (using chloroform), glycolipids (using acetone) and phospholipid fractions (using methanol). The PLFA fraction was collected and evaporated under a stream of compressed N2 in a heating block at 36 °C37.

PLFA fraction samples were re-suspended in 1 mL MeOH: toluene (1:1 volume ratio) and trans-esterified to fatty acid methy esthers (FAMEs), using 1 mL 0.2 M KOH dissolved in methanol. For liquid extraction, 2 mL of hexane: chloroform (4:1 volume ratio), 0.3 mL acetic acid (1.0 M), and 2 mL ultrapure water were added. Two internal standards (C13 and C19) were added to the samples before evaporating FAMEs under a stream of compressed N2.Samples were resuspended in hexane prior to GC analysis. PLFAs were identified and quantified using gas-chromatography37.

Individual PLFAs were identified using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) using an Agilent Technologies 5973 Mass Selective Detector (electron impact ionisation 70Ev, scan mode) coupled to an Agilent Technologies 6890 GC fitted with a 50 m × 0.32 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm CP-Sil 5CB fused silica capillary column. The temperature program was as follows: 50 °C (5) – 150 @ 10 °C min− 1 – 270 @ 3 °C min− 1 – 320 @ 20 °C min− 1.

δ13C values of individual PLFAs were analysed using gas chromatography-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC-C-IRMS). Compounds were first separated using an Agilent Technologies 6890 series gas chromatograph (splitless mode; 50 m x 0.32 mm x 0.2 μm CP-SIL 5CB column). The temperature was held isothermally at 50 °C for 5 min and then ramped from 50 to 150 °C at 10 °C min− 1; to 270 at 3 °C min− 1; to 340 at 20 °C (with a 5 min). He2 was used as the carrier gas. The GC effluent was diverted via a heart split union to a ceramic combustion furnace (650 mm × 0.3 mm i.d.) which was packed with a copper oxide/platinum/nichrome catalyst wire which was heated to 940 °C. Water was removed from the combustion products by passing the effluent through a nafion membrane, before the CO2 entering the isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) (Isoprime Ltd). PLFA δ13C values were corrected for the additional carbon atom introduced during methylation, using a correction factor obtained by CF-EA-IRMS measurement on the derivatising methanol and application of the mass balance Eq. 44, where NPLFA is the number of carbon atoms in the PLFA molecule, 13CFAME is the δ13C values of the methylated PLFA, and 13CMeOH is the δ13C value of the methanol used for methylation (-37‰):

Standard PLFA nomenclature (A: BωC) was used, where A refers to the total number of carbon atoms, B refers to the number double bonds, and C refers to the location of double carbon bonds. ‘A’, ‘i’, ‘cy’, and ‘me’ refer to anteiso-, iso-, cyclopropane and methyl groups, respectively45. C15:0i, C15:0a, C16:0i, C17:0i and C17:0a PLFA biomarkers were assigned to Gram positive bacteria. C16:1ω7, C17:0, C18:1ω7, and 7,8Cy-C19:0 were assigned to Gram negative bacteria. C18:2ω6c and C18:1ω9c were assigned to fungal biomarkers. C14:0, C15:0, C16:1ω6, C16:0, C17:1ω8, 10Me-C16:0, C17:1, C18:0, and 10Me-C18:0 biomarkers were left unclassified due to a lack of specificity to any microbial group37.

Peat biogeochemical properties

Moisture content was determined by through the mass of water lost from 10 g wet weight peat oven dried at 105 °C for 24 h. Organic matter content was determined as the mass lost after ignition for 7 h at 550 °C. pH, conductivity and redox potential in each pot were determined using a 1:5 ratio of peat to deionized water. Total carbon (C) and total nitrogen (N) were quantified from 0.2 g of dry, homogenised peat and combusted using a total element analyser (Flash EA 1112, CE Instruments, Wigan, UK).

Isotopic calculations

Natural abundances of 13C are typically expressed as δ13C (‰), which describes the ratios (R) of 13C and 12C relative to the standard. δ13C values were calculated as:

Atom %, the absolute number of atoms of a given isotope in 100 atoms of an element29, was calculated in our pot experiment from labelled CH4 fluxes and PLFAs relative to pre-pulse measurements as:

where AR equals the absolute ratio (0.0112372) of PDB standard material. Atom % was subsequently used to calculate 13C enrichment of CH4 fluxes relative to unlabelled natural abundance control plants of the same species (Table 1). 13C excess was calculated as:

CH4 fluxes were calculated using the ideal gas law and assuming the linear accumulation of gases over time within the chamber. CH4 fluxes from labelled plants comprised both pre-existing natural abundance 13C as well as 13C derived from the pulse. Natural abundance 13C was quantified using measurements from prior to labelling and from unlabelled plants, which were comparable. Excess CH4 was calculated as CH4 post-labelling minus mean CH4 flux from unlabelled plants. The 13CH4 flux (ng) was calculated using atom % data and the net flux rate.

Statistical analyses

Differences in CH4 fluxes between paired girdled and control trees were assessed using a mixed effects model. CH4 fluxes were transformed using the box-cox transformation (CH4 − 0.2). Differences in δ13C, atom % 13CH4 fluxes, PLFA abundances and PLFA enrichment were also assessed using a linear mixed effects model. Statistical models of CH4 fluxes included plant types and sampling day. Excess 13CH4 fluxes were log-transformed Significance was assessed p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in GenStat (v17.1).

Results

Tree girdling

Prior to girdling, the peat ranged from being a small source to a small sink of CH4. Immediately following girdling, there were no significant differences in CH4 fluxes between girdled trees and the controls (p = 0.934; Fig. 1). However, by 14 days post-girdling, CH4 fluxes adjacent to girdled trees were significantly lower than the controls (p = 0.047). Mean CH4 fluxes were 67 ± 14% lower from girdled trees, suggesting a substantial contribution of root inputs to peat surface CH4 fluxes.

Natural abundance labelling

CH4 fluxes indicated that the peat was a consistent source of CH4 (Fig. 2a), with peak fluxes of 3.7 mg CH4 m− 2 hr− 1 and mean fluxes of 1.02 ± 0.31 mg CH4 m− 2 hr− 1. Addition of the natural abundance label resulted in a significant increase in the δ13C signature of CH4 compared to the controls (F1,30 = 7.44, p = 0.011), with the response observable within four days of labelling (Fig. 2b).

13CO2 labelling

CH4 emissions measured under both plant types showed significant enrichment 24 h following pulse-labelling (F4,26.6 = 12.9, p < 0.001, Fig. 3a,b), with 13C atom excess decreasing over time. There was no significant difference in 13C atom excess between plant types (F1,7 = 0.34, p = 0.58), but there was a significant interaction between plant types and number of days post-labelling (F4,26.6 = 2.81, p = 0.045), indicating differences in the rate of response between species.

Excess CH4 fluxes differed significantly between different plant types (F1,7 = 11.45, p = 0.01). Mean fluxes from palms were significantly larger than those of broadleaved evergreen saplings (Fig. 3c). Although fluxes were variable over time, and there was a large decline in fluxes 14 days post labelling (coinciding with a decline in 13C atom excess), there was no significant difference in excess 13CH4 fluxes over time (F3,21 = 1.63, p = 0.21). Moreover, as palm fluxes were consistently larger, the interaction term between plant type and days post-labelling was also not significant (F1,21 = 0.33, p = 0.80). Excess 13CH4 was significantly greater under palms (F1,7 = 22.62, p = 0.002, Fig. 3d). Between one and seven days post-labelling, the excess 13CH4 fluxes remained consistently above 100 ng m− 2 hr− 1, but by day 14 declined to almost zero, through a combination of declining 13C atom excess, and reduced net CH4 fluxes.

PLFA and 13C-PLFA

There was no significant difference in total PLFA concentrations between broadleaved and palm plant types (F1,7 = 0.02, p = 0.90), and no difference between fungal (F1,7 = 0.11, p = 0.75), total bacterial (F1,7 = 0.01, p = 0.92), Gram positive (F1,7 = 0.0, p = 0.99) or Gram negative (F1,7 = 0.04, p = 0.85) PLFAs (Fig. 4b). As a percentage of total PLFAs, 8.8–9.4% of PLFAs were fungal, 26.9–28.9% were Gram positive, 39.6–42.5% were Gram negative, and 21.2–22.7% were non-specific (Fig. 4c). Fungi-bacteria ratios were consistent between plant types (0.13), as were ratios of Gram positive to Gram negative bacteria (0.64–0.73).

There was widespread enrichment of PLFA biomarkers seven days post labelling (Fig. 5a). There was, however, no significant difference in excess total (F1,7 = 1.35, p = 0.28), bacterial (F1,7 = 1.02, p = 0.35), fungal (F1,7 = 2.87, p = 0.13), Gram positive (F1,7 = 1.34, p = 0.29), or Gram negative (F1,7 = 0.6, p = 0.46) PLFAs (Fig. 5b). There were, however, significant differences in the percentage enrichment of both Gram positive and Gram negative PLFAs relative to total PLFA enrichment (Fig. 5c). Gram positive PLFAs were significantly more enriched for the palm (F1,7 = 6.39, p = 0.04), whereas Gram negative PLFAs were more enriched under the broadleaved evergreen plants (F1,7 = 5.70, p = 0.048).

Discussion

Root carbon inputs drive CH4 fluxes

The results from our studies demonstrate that exudates of carbon compounds from roots contributed to methane production and emissions. The 67% decrease in CH4 fluxes following girdling demonstrates that plant root inputs contribute significantly to peat surface emissions. This high apparent proportion of root contribution to surface CH4 fluxes is supported by the approximately two-third contribution of roots to CO2 fluxes we have previously demonstrated at the site46. Girdling will also have driven a reduction in rhizosphere respiration (including root respiration) by reducing the flow of exudates to the roots and peat21. It may also have reduced oxygen consumption within the rooting zone therefore leading to favourable conditions for methanotrophy although plant stem adaptations to supply oxygen to roots (lenticels) which are present for both C. panamensis and S. globulifera may have confounding effects10.

The significant enrichment following stem labelling in situ provides additional supporting evidence of the pathway, namely labile carbon transported in the plant vascular tissue contribute to CH4 emissions from tropical peatlands. The relatively high baseline values compared to post-labelling measurements most likely reflects natural environmental variability in the δ13C signature of CH4 arising from plant diurnal cycles, changes in water level, and temperature (Fig. 2b)47. The 13CO2 labelling results suggest that the contribution of root carbon inputs to CH4 fluxes varies between contrasting plant functional types, for example palms versus broadleaved evergreen trees, and that root inputs of carbon are derived from recent photosynthetically fixed carbon. We also demonstrate that a varied microbial community is responsible for utilising plant carbon inputs.

Previous studies investigating the role of labile carbon inputs on peatland CH4 dynamics have proposed a possible positive priming effect48,49,50, whereby the addition of an alternative carbon source (for example root exudates or plant litter) drives an increase in the microbial utilisation of organic matter51, although results are not always consistent between studies8. In our study we do not show any direct evidence of priming effects.,. These differences may be a consequence of the importance of root exudate component composition and concentration in regulating responses9. However, our results do demonstrate the close coupling of plant productivity and CH4 production. As a result, our findings have profound implications in assessing the potential response of peatland GHG fluxes to environmental change including alterations in temperature and increases in atmospheric CO2. Other studies have also highlighted the close correlation between plant productivity and wetland CH4 production13,16 and as a consequence any process which alters plant root inputs could significantly affect peat surface CH4 fluxes, possibly mediated through changes to both the composition and concentration of root exudate profiles8,9. These effects may be further exacerbated when combined with the high degree of temperature sensitivity of peat CH4 fluxes, and the projtected climate warming of tropical peatlands in the future52,53,54. Evidence that CH4 dynamics may respond to exogenous labile carbon input raises the possibility that, depending on the any changes in the relative allocation of labile vs. recalcitrant litter input from trees, may shift peatlands away from a current carbon input/output equilibria.

The role of plant functional types

The isotopic enrichment of CH4 fluxes (Figs. 2a and 3) demonstrates a conclusive link between ongoing recently fixed carbon and methanogenic activity in tropical peatlands. In tropical wetland ecosystems, this link has previously only been demonstrated in rice paddy soils55. The response was relatively rapid, with changes in δ13C measured within 24 h of labelling in the case of saplings, and by four days following natural abundance labelling. The rapid response following 13CO2 labelling is most likely the result of a relatively short path length (all plants were less than 50 cm tall) which would allow rapid transfer of the label to the roots prior to exudation. Mean residence time is partially dependent on plant size and height, with full grown trees having longer residency in plant tissues56. There was no significant effect of girdling immediately following treatment, with effects detectable within 14 days. This likely reflects lags in the shutdown of delivery of metabolites, combined with the continued exudation of stored carbon in roots.

The significant interaction between plant type and number of days post-labelling suggests more rapid transfer of recently fixed carbon under broadleaved plants compared to palms, although the limited number of species investigated means that it is hard to ascribe any differences to a plant functional type effect rather than specific species differences. Mean residency times in leaf tissues are known to be variable between contrasting plant functional types, such as plants vs. shrubs57 and C4 vs. C3 plants58. Previously, it has been suggested that different plant functional types may respond differently to changing environmental conditions within chambers during labelling and sample collection, possibly resulting in differences in assimilation of 13CO229,59. Moreover, palms and broadleaved trees are known to have distinct differences in vascular tissue between monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants, with monocotyledonous species (which includes palms) featuring vascular bundles scattered throughout the stem, compared to a distribution around the edges of the stem in dicotyledonous species60. These differences may, in part, account for observed differences in fluxes, as plant vascular tissue can be a significant conduit for gas transport from the soil to the atmosphere61. Further differences may be due to contrasting root exudate inputs, as root exudate composition and concentration is known to vary between plant species8,9.

Microbial assimilation of 13C in tropical peatlands

PLFA biomarkers have been widely used to profile peat microbial community structure, as they are ubiquitous membrane spanning lipids found only in live cells and not microbial necromass37,62. Moreover, when combined with stable isotope labelling, 13C enrichment of biomarkers is a useful tool for assessing differences in microbial community function.

Total and specific PLFA biomarker abundance were consistent between microbial communities under both plant types. Both peat types are dominated by Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria consistent with measurements made in other forest soils in Panama10,37,63,64,65. Previous microbial community characterisations of peat from Changuinola have noted a dominance of Acidobacteria (a phylum of Gram negative bacteria)43, a finding also reported for other tropical66 and temperate peats67. Fungal abundance was low (8.8–9.4%), possibly due to the anoxic conditions arising from continual inundation by the water Tables40,43,66.

Enrichment of a range of PLFA biomarkers demonstrates that the 13C pulse can be utilised by a broad range of microorganisms, a finding that demonstrates that recent photosynthates are important drivers of microbial carbon dynamics in tropical peatlands as in other ecosystems26,68,69. Enrichment was most pronounced in C15:0i and C15:0a biomarkers for Gram positive bacteria, C18:1ω7 for Gram negative, and C18:1ω9c for fungi. The significant enrichment of Gram negative biomarkers in both peat types indicates an important role in utilising labile carbon inputs70,71. Gram negative biomarkers were strongly enriched relative to Gram positive biomarkers for the broadleaved plants but less so for the palm (Fig. 5), suggesting functional differences between microbial communities under contrasting vegetation. PLFA biomarker enrichment was, however, measured 14 days following labelling, and therefore some enrichment of microbial groups may be driven not by direct use of root exudates but through secondary consumption of dead microbial and root biomass63. Previously, Gram positive bacteria have been suggested as important in utilising more recalcitrant carbon22,34, as well as assimilating label derived from dead fungal or root biomass rather than from root exudates72,73. Fungal biomarkers were also significantly enriched indicating that, despite low abundance, fungi are also important in tropical peatland decomposition processes. Previously, it has been proposed that peatland microbial communities exhibit a certain degree of functional redundancy, whereby both fungal and bacterial communities are able to utilise a similar range of substrates and drive microbial production of CO274,75,76.

It should be noted that as a technique, PLFA analysis does not detect methanogenic Archaea as they contain ether-linked rather than ester-linked lipids77,78. PLFA biomarkers for methanotrophs have, however, been previously reported. PLFAs comprising C14 and C16 generally dominate type I methanotrophs (generally assumed to dominate in low CH4 environments), whereas C18 fatty acids predominate in type II methanotrophs (which favour greater CH4 concentrations)79,80. Specific type I methanotroph biomarkers include, C16:1ω5, C16:1ω7, C16:1ω8c and C16:1ω11c, and C18:1ω7c C18:1ω8c for type II methanotrophs80,81,82,83. In this study both 18:1ω7c, and 16:1ω5 were identified and were present at similar abundances (Fig. 4a), and showed significant enrichment (Fig. 5a) potentially indicating the presence of both type I and type II methanotrophs using enriched CH484.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that peat inputs of labile carbon from roots, derived from recent carbon fixation, make a significant contribution to peat CH4 production and surface CH4 emission, and that the extent of this contribution varies significantly between contrasting plant functional types. Despite similar microbial community structure between plant types, there were significant differences in isotopic enrichment of Gram positive and Gram negative populations, with the former showing increased enrichment in peat under broadleaved evergreen plants. These results are of particular importance in understanding microbial community function under contrasting vegetation types, owing to differences in the extent of the response of CH4 fluxes and microbial community enrichment. The intrinsic relationship between plant productivity and peat CH4 production, mediated through plant root inputs, have significant implications for the response of peatland CH4 fluxes to environmental change.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Girkin, N. T. & Davidson, S. J. Protect peatlands to achieve climate goals. Science 383, 490 (2024).

Crezee, B. et al. Mapping peat thickness and carbon stocks of the central Congo Basin using field data. Nat. Geosci. 15, 639–644 (2022).

Garcin, Y. et al. Hydroclimatic vulnerability of peat carbon in the central Congo Basin. Nature 612, 277–282 (2022).

Loisel, J. et al. Expert assessment of future vulnerability of the global peatland carbon sink. Nat. Clim. Change. 11, 70–77 (2021).

Upton, A., Vane, C. H., Girkin, N., Turner, B. L. & Sjögersten, S. Does litter input determine carbon storage and peat organic chemistry in tropical peatlands? Geoderma 326, 76–87 (2018).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. et al. Quality not quantity: Organic matter composition controls of CO2 and CH4 fluxes in neotropical peat profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 103, 86–96 (2016).

Pangala, S. R. et al. Large emissions from floodplain trees close the Amazon methane budget. Nature 552, 230–234 (2017).

Girkin, N. T., Turner, B. L., Ostle, N., Craigon, J. & Sjögersten, S. Root exudate analogues accelerate CO2 and CH4 production in tropical peat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 117, 48–55 (2018).

Girkin, N. T., Turner, B. L., Ostle, N. & Sjögersten, S. Composition and concentration of root exudate analogues regulate greenhouse gas fluxes from tropical peat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 127, 280–285 (2018).

Girkin, N. T., Vane, C. H., Turner, B. L., Ostle, N. J. & Sjӧgersten, S. Root oxygen mitigates methane fluxes in tropical peatlands. Environ. Res. Lett. 11 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8495 (2020).

Hirano, T., Jauhiainen, J., Inoue, T. & Takahashi, H. Controls on the Carbon Balance of Tropical Peatlands. Ecosystems 12, 873–887 (2009).

Wright, E. L., Black, C. R., Turner, B. L. & Sjögersten, S. Environmental controls of temporal and spatial variability in CO2 and CH4 fluxes in a neotropical peatland. Glob. Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12330 (2013).

Weigel, H. J. et al. Carbon turnover in a crop rotation under free air CO2 enrichment (FACE). PEDOSPHERE (2005).

Thomas, J., Davies, K. L. & Lloyd, D. K. L.; B. Role of wetland plants in the diurnal control of CH4 and CO2 fluxes in peat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28, (1996).

Lu, Y. H., Murase, J., Watanabe, A., Sugimoto, A. & Kimura, M. Linking microbial community dynamics to rhizosphere carbon flow in a wetland rice soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48, 179–186 (2004).

Whiting, G. J. & Chanton, J. P. Plant-dependent CH4 emission in a subarctic Canadian Fen. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1029/92GB00710 (1992).

Smith, W. H. Character and significance of Forest Tree Root exudates. Ecology 57, 324–331 (1976).

Joabsson, A., Christensen, T. R. & Wallen, B. Vascular plant controls on methane emissions from northern peatforming wetlands. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 385–388 (1999).

Kao-Kniffin, J. & Zhu, B. A. Microbial link between elevated CO2 and methane emissions that is Plant Species-Specific. Microb. Ecol. 66, 621–629 (2013).

Sjögersten, S. et al. Methane emissions from tree stems in neotropical peatlands. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16178 (2019).

Bhupinderpal-Singh et al. Tree root and soil heterotrophic respiration as revealed by girdling of boreal scots pine forest: extending observations beyond the first year. Plant, Cell Environ. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01053.x (2003).

Tavi, N. M. et al. Linking microbial community structure and allocation of plant-derived carbon in an organic agricultural soil using (CO2)-C-13 pulse-chase labelling combined with C-13-PLFA profiling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 58, 207–215 (2013).

Elias, D. et al. Functional differences in the microbial processing of recent assimilates under two contrasting perennial bioenergy plantations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 114, 248–262 (2017).

Subke, J. A. et al. Short-term dynamics of abiotic and biotic soil (CO2)-C-13 effluxes after in situ (CO2)-C-13 pulse labelling of a boreal pine forest. New Phytol. 183, 349–357 (2009).

Epron, D. et al. Seasonal variations of belowground carbon transfer assessed by in situ (CO2)-C-13 pulse labelling of trees. Biogeosciences 8, 1153–1168 (2011).

De Deyn, G. B., Quirk, H., Oakley, S., Ostle, N. & Bardgett, R. D. Rapid transfer of photosynthetic carbon through the plant-soil system in differently managed species-rich grasslands. Biogeosciences 8, 1131–1139 (2011).

Ostle, N. et al. Isotopic detection of recent photosynthate carbon flow into grassland rhizosphere fauna. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 768–777 (2007).

Fenner, N., Ostle, N., Freeman, C., Sleep, D. & Reynolds, B. Peatland carbon afflux partitioning reveals that Sphagnum Photosynthate contributes to the DOC pool. Plant. Soil. 259, 345–354 (2004).

Ward, S. E., Bardgett, R. D., McNamara, N. P. & Ostle, N. J. Plant functional group identity influences short-term peatland ecosystem carbon flux: evidence from a plant removal experiment. Funct. Ecol. 23, 454–462 (2009).

Pump, J., Pratscher, J. & Conrad, R. Colonization of rice roots with methanogenic archaea controls photosynthesis-derived methane emission. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 2254–2260 (2015).

Ostle, N., Ineson, P., Benham, D. & Sleep, D. Carbon assimilation and turnover in grassland vegetation using an in situ (CO2)-C-13 pulse labelling system. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 14, 1345–1350 (2000).

Churchland, C., Weatherall, A., Briones, M. J. I. & Grayston, S. J. Stable-isotope labeling and probing of recent photosynthates into respired CO2, soil microbes and soil mesofauna using a xylem and phloem stem-injection technique on Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis). Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 26, 2493–2501 (2012).

Treonis, A. M. et al. Identification of groups of metabolically-active rhizosphere microorganisms by stable isotope probing of PLFAs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 533–537 (2004).

Kramer, C. & Gleixner, G. Variable use of plant- and soil-derived carbon by microorganisms in agricultural soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 3267–3278 (2006).

Denef, K., Roobroeck, D., Wadu, M. C. W. M., Lootens, P. & Boeckx, P. Microbial community composition and rhizodeposit-carbon assimilation in differently managed temperate grassland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41, 144–153 (2009).

Tavi, N. M. et al. Impact of Phalaris arundinacea cultivation on microbial community of a cutover peatland. Boreal Environ. Res. 15, 437–445 (2010).

Girkin, N. T. et al. Peat Properties, Dominant Vegetation Type and Microbial Community structure in a Tropical Peatland. Wetlands https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01287-4 (2020).

Phillips, S., Rouse, G. E. & Bustin, R. M. Vegetation zones and diagnostic pollen profiles of a coastal peat swamp, Bocas Del Toro, Panama. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 128, 301–338 (1997).

Sjögersten, S., Cheesman, A. W. & Lopez, O. Turner L., B. Biogeochemical processes along a nutrient gradient in a tropical ombrotrophic peatland. Biogeochemistry 104, 147–163 (2011).

Chambers, L. G., Guevara, R., Boyer, J. N., Troxler, T. G. & Davis, S. E. Effects of Salinity and Inundation on Microbial Community structure and function in a Mangrove Peat Soil. Wetlands 36, 361–371 (2016).

Wright, E. L., Black, C. R., Cheesman, A. W., Turner, B. L. & Sjögersten, S. Impact of simulated changes in Water table depth on Ex situ decomposition of Leaf Litter from a Neotropical Peatland. Wetlands 33, 217–226 (2013).

Girkin, N. T. et al. Spatial variability of organic matter properties determines methane fluxes in a tropical forested peatland. Biogeochemistry 142, 231–245 (2019).

Troxler, T. G. et al. Patterns of soil Bacteria and Canopy Community structure related to Tropical Peatland Development. Wetlands 32, 769–782 (2012).

Jones, D. M., Carter, J. F., Eglinton, G., Jumeau, E. J. & Fenwick, C. S. Determination of Delta-C-13 values of sedimentary straight Chain and cyclic alcohols by gas-chromatography isotope ration Mass-Spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 20, 641–646 (1991).

Kong, A. Y. Y., Scow, K. M., Cordova-Kreylos, A. L., Holmes, W. E. & Six, J. Microbial community composition and carbon cycling within soil microenvironments of conventional, low-input, and organic cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 20–30 (2011).

Girkin, N. T., Turner, B. L., Ostle, N. & Sjögersten, S. Root-derived CO 2 flux from a tropical peatland. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 26, 985–991 (2018).

Veselý, L. et al. Strong temporal variation of consumer δ13C value in an oligotrophic reservoir is related to water level fluctuation. Sci. Rep. 13, 3642 (2023).

Basiliko, N., Stewart, H., Roulet, N. T. & Moore, T. R. Do Root Exudates Enhance Peat Decomposition? Geomicrobiol J. 29, 374–378 (2012).

Hamer, U. Priming effects of dissolved organic substrates on the mineralisation of lignin, peat, soil, organic matter and black carbon determined, with 14 C and 13 C isotope techniques (vol. PhD (Ruhr-Universität, 2004).

Hamer, U. & Marschner, B. Priming effects of sugars, amino acids, organic acids and catechol on the mineralization of lignin and peat. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Science-Zeitschrift Fur Pflanzenernahrung Und Bodenkunde. 165, 261–268 (2002).

Kuzyakov, Y. & Review Factors affecting rhizosphere priming effects. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Science-Zeitschrift Fur Pflanzenernahrung Und Bodenkunde. 165, 382–396 (2002).

Sjögersten, S. et al. Temperature response of ex-situ greenhouse gas emissions from tropical peatlands: interactions between forest type and peat moisture conditions. Geoderma https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.02.029 (2018).

Girkin, N. T. et al. Tropical peatlands in the Anthropocene: the present and the future. Anthropocene 100354, (2022).

Girkin, N. T. et al. Interactions between labile carbon, temperature and land use regulate carbon dioxide and methane production in tropical peat. Biogeochemistry 147, 87–97 (2020).

Cheng, W. et al. Effect of elevated [CO(2)] on soil bubble and CH(4) Emission from a Rice Paddy: a test by (13)C pulse-labeling under Free-Air CO(2) Enrichment. Geomicrobiol J. 25, 396–403 (2008).

Hogberg, P. et al. High temporal resolution tracing of photosynthate carbon from the tree canopy to forest soil microorganisms. New Phytol. 177, 220–228 (2008).

Carbone, M. S. & Trumbore, S. E. Contribution of new photosynthetic assimilates to respiration by perennial grasses and shrubs: residence times and allocation patterns. New Phytol. 176, 124–135 (2007).

Ueno, O., Kawano, Y., Wakayama, M. & Takeda, T. Leaf vascular systems in C-3 and C-4 grasses: a two-dimensional analysis. Ann. Botany. 97, 611–621 (2006).

Pumpanen, J. et al. Comparison of different chamber techniques for measuring soil CO2 efflux. Agric. For. Meteorol. 123, 159–176 (2004).

Scarpella, E. & Meijer, A. H. Pattern formation in the vascular system of monocot and dicot plant species. New Phytol. 164, 209–242 (2004).

Pangala, S. R., Moore, S., Hornibrook, E. R. C. & Gauci, V. Trees are major conduits for methane egress from tropical forested wetlands. New Phytol. 197, 524–531 (2013).

Zelles, L. Fatty acid patterns of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides in the characterisation of microbial communities in soil: a review. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 29, 111–129 (1999).

Nottingham, A. T., Griffiths, H., Chamberlain, P. M., Stott, A. W. & Tanner, E. V. J. Soil priming by sugar and leaf-litter substrates: a link to microbial groups. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 42, 183–190 (2009).

Nottingham, A. T., Turner, B. L., Chamberlain, P. M., Stott, A. W. & Tanner, E. V. J. Priming and microbial nutrient limitation in lowland tropical forest soils of contrasting fertility. Biogeochemistry 111, 219–237 (2012).

Nottingham, A. T. et al. Root and arbuscular mycorrhizal mycelial interactions with soil microorganisms in lowland tropical forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 37–50 (2013).

Jackson, C. R., Liew, K. C. & Yule, C. M. Structural and functional changes with depth in Microbial communities in a Tropical Malaysian Peat Swamp Forest. Microb. Ecol. 57, 402–412 (2009).

Dedysh, S. N., Pankratov, T. A., Belova, S. E., Kulichevskaya, I. S. & Liesack, W. Phylogenetic analysis and in situ identification of Bacteria community composition in an acidic Sphagnum peat bog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2110–2117 (2006).

Ostle, N. et al. Active microbial RNA turnover in a grassland soil estimated using a (CO2)-C-13 spike. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 877–885 (2003).

Ward, S. E. et al. Fire accelerates assimilation and transfer of Photosynthetic Carbon from plants to Soil microbes in a Northern Peatland. Ecosystems 15, 1245–1257 (2012).

Bird, J. A., Herman, D. J. & Firestone, M. K. Rhizosphere priming of soil organic matter by bacterial groups in a grassland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 718–725 (2011).

Koranda, M. et al. Fungal and bacterial utilization of organic substrates depends on substrate complexity and N availability. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 87, 142–152 (2014).

Denef, K. et al. Community shifts and carbon translocation within metabolically-active rhizosphere microorganisms in grasslands under elevated CO2. Biogeosciences 4, 769–779 (2007).

Balasooriya, W. K., Denef, K., Peters, J., Verhoest, N. E. C. & Boeckx, P. Vegetation composition and soil microbial community structural changes along a wetland hydrological gradient. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 277–291 (2008).

Rousk, J., Brookes, P. C. & Baath, E. Contrasting Soil pH effects on Fungal and Bacterial Growth Suggest Functional redundancy in Carbon Mineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 1589–1596 (2009).

Myers, B., Webster, K. L., Mclaughlin, J. W. & Basiliko, N. Microbial activity across a boreal peatland nutrient gradient: the role of fungi and bacteria. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 20, 77–88 (2012).

Haynes, K. M., Preston, M. D., McLaughlin, J. W., Webster, K. & Basiliko, N. Dissimilar bacterial and fungal decomposer communities across rich to poor Fen peatlands exhibit functional redundancy. Can. J. Soil Sci. 95, 219–230 (2015).

Gattinger, A., Gunther, A., Schloter, M. & Munich, J. C. Characterisation of Archaea in soils by polar lipid analysis. Acta Biotechnol. 23, 21–28 (2003).

Palojarvi, A. Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analyses. in Microbiological Methods for Assessing Soil Quality (eds Bloem, J., Hopkins, D. W. & Benedetti, A.) (CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, (2005).

Hanson, R. S. & Hanson, T. E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60, 439–471 (1996).

Singh, B. K. et al. Effect of afforestation and reforestation of pastures on the activity and population dynamics of methanotrophic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5153–5161 (2007).

Roslev, P. & Iversen, N. Radioactive fingerprinting of microorganisms that oxidize atmospheric methane in different soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 4064–4070 (1999).

Mills, C. T. et al. The relative contribution of methanotrophs to microbial communities and carbon cycling in soil overlying a coal-bed methane seep. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 84, 474–494 (2013).

Maxfield, P. J., Hornibrook, E. R. C. & Evershed, R. P. Estimating high-affinity methanotrophic bacterial biomass, growth, and turnover in soil by phospholipid fatty acid C-13 labeling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3901–3907 (2006).

Bull, I. D., Parekh, N. R., Hall, G. H., Ineson, P. & Evershed, R. P. Detection and classification of atmospheric methane oxidizing bacteria in soil. Nature 405, 175–178 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council [grant numbers NE/L002604/1] to S.S., a NERC grant [grant number NE/J010928/1] to V.G. and S.S., and the AXA Research Fund to V.G. V.G. further acknowledges support from the NERC consortium MOYA [grant NE/N015606/1]. N.T.G. acknowledges a Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute short-term fellowship. We would also like to thank Eric Brown for his support in the field, the staff at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama City and Bocas Del Toro for their logistical support, and James Verran and Dr Saul Vasquez Reina at the University of Nottingham, and Dr Annette Ryan at Lancaster University for analytical support. We thank ANAM for granting research permits SE/P-29-13 and SE/P-34-13 under which this research was conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.T.G., S.S., N.O., A.Siegenthaler. and V.G. devised the studies. N.T.G. and A.Siegenthaler carried out the fieldwork and analysed samples with A.Stott. N.T.G and S.S. analysed the data. N.T.G. wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to subsequent revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Girkin, N.T., Siegenthaler, A., Lopez, O. et al. Plant root carbon inputs drive methane production in tropical peatlands. Sci Rep 15, 3244 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87467-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87467-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Tree methane exchange in a changing world

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Plant controls over tropical wetland nitrous oxide dynamics: a review

Tropical Ecology (2025)