Abstract

The perovskite solar cell has been the subject of intense breakdown lately because of its exceptional efficiency. Nevertheless, they confront a significant challenge due to the absorber layer’s (perovskite) sensitivity to oxygen and water, which can cause rapid material degradation and adversely affect the solar cell’s performance. The commonly used organic hole transport layer (HTL), Spiro-OMeTAD, tends to degrade over time, exacerbating the issue. To address this challenge, two-stage research was conducted. Initially, the CH3NH3PbI3 thin film was experimentally prepared, and XRD analysis confirmed the material’s satisfactory crystalline phase (tetragonal), with a crystal size of 73.9 nm. An energy band gap of 1.55 eV was obtained experimentally, demonstrating good correspondence with the literature. Then, perovskites with different crystal structures (cubic, tetragonal, and orthorhombic) were calculated by DFT. These calculations obtained energy band gaps with values of 1.5 eV for the cubic, 1.7 eV for the tetragonal, and 3.9 eV for the orthorhombic. Subsequently, a numerical simulation study using SCAPS was carried out to validate the theoretical performance of an experimental solar cell with Spiro-OMeTAD as the HTL. Also, a simulation without HTL was performed to highlight its importance. Finally, comparative studies were conducted to evaluate the feasibility of incorporating CdTe and CIGS as inorganic absorbing layers within perovskite solar cells (MAPI). The objective was to investigate their potential for cooperative behavior in light absorption and charge transport. The findings indicated that the CIGS absorbing layer outperformed both materials, achieving an efficiency of 15.67%. Furthermore, an optimization study for the CIGS layer was performed, resulting in enhanced output parameters, including a maximum efficiency of 28.32%. This research represents a significant advancement in developing stable and efficient perovskite solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

MAPI (methylammonium lead iodide) has garnered substantial attention in recent years. Their remarkable energy conversion efficiency and cost-effectiveness in production have propelled them to the forefront of solar cell technology. Efforts to optimize the performance of PSCs have been underway since 2009, when the efficiency of a CH3NH3PbI3 cell reached 3.8%1. Significant progress has been made in recent years, resulting in a remarkable increase in power conversion efficiency (PCE) to over 25%2. However, the instability of the perovskite in humid environments and the toxicity of the material used for charge transport, Spiro-OMeTAD, have been significant challenges for its large-scale commercialization3. Therefore, several studies have been conducted to find more stable alternatives to Spiro-OMeTAD3,4,5,6.

The Hole Transport Layer (HTL) and Electron Transport Layer (ETL) are crucial in the perovskite solar cell. They play a vital role in energy band alignment with the absorber, which directly influences the conduction of charge carriers to the front and back contacts6. Therefore, the common ETLs used are PCBM, IGZO, SnO2, TiO2, ZnO, CdS, CdSe, In2S, SnS2, ZnS, ZnSe, MoSe2, MoS2, and as HTLs, some materials such as Spiro-OMeTAD, P3HT, CuI, NiO, CuSCN, PEDOTPSS, NPB, MEH-PPV, CuAlTe2, CdTe, CuSeCN, NiOx, CuSCN, CuI, Cu2O, MoOx, WO3, CuS, Vox, and CZTS have been studied extensively to compare their properties and their effect on the stability and efficiency of PSCs7,8,9,10,11,12,13.

The high cost of producing organic HTLs, attributed to the need for tedious synthetic protocols and high purity requirements, poses a significant challenge to commercializing perovskite solar cells (PSCs)3. As such, exploring new HTLs to facilitate the future development of PSCs is imperative. Inorganic HTLs, which are easy to synthesize, employ abundant materials, have a low production cost, and possess an energy level that matches well with perovskite materials, represent a promising alternative. Given these advantages, inorganic HTLs hold great potential to address the future obstacles related to the commercialization of PSCs14.

The substitution of Spiro-OMeTAD for CdTe or CIGS in MAPI perovskite solar cells is a promising alternative due to these materials’ high efficiency and stability. These materials have shown similar perovskite characteristics. For example, CdTe has an Eg of 1.44 eV, an absorption coefficient of 105 cm−1, and an efficiency of 22.3%15, and CIGS shows an Eg of 1.1 eV, an α around 105 cm−1, and an efficiency of 23.35%16. Furthermore, using CdTe and CIGS as charge transport materials could enhance the stability of MAPI devices in humid environments. Recent discoveries indicate that CdTe can also serve as a charge transport material in MAPI devices, resulting in an efficiency of 19.3%, as demonstrated by Xiao et al.17. On the other hand, the research conducted by Jošt et al.18 sheds light on developing monolithic perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells. Their findings show a certified PCE of 21.6%, which is a remarkable accomplishment. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate the possibility of using CdTe and CIGS in perovskite solar cells in n–i–p structures due to the possibility of making their deposits at low temperatures19,20.

Further research is needed to optimize the performance of these materials in MAPI perovskite solar cells. Studies have shown good approximations in theoretical results for perovskite solar cells using DFT and SCAPS21,22. Therefore, this research developed the experimental and theoretical calculations (DFT) of the MAPI crystal structures. Subsequently, the properties obtained before were considered for a comparative analysis using simulation solar cells by SCAPS-1D to investigate the effect of incorporating inorganic layers (CdTe and CIGS).

Methodology experimental details

Device fabrication

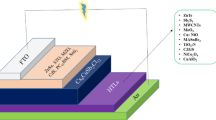

As per a previous work23, the PVK (CH3NH3PbI3) solar cell to be studied has a n–i–p configuration of FTO/c-TiO2/m-TiO2/PVK/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au.

Characterization techniques

The PVK films were made on FTO glass/ compact and mesoporous TiO2 and analyzed by X-ray diffractions (Rigaku DMAX-2200, with Cu-K α(l ¼ 1.54 Å), in the 2θ from 5° to 60°. The films. The crystal sizes from the XRD patterns corresponding to the crystalline plane of (110) were calculated using the Scherrer equation. A MAPI perovskite was used to calculate the lattice parameters of the tetragonal unit cell. The MAUD software was used to perform a Rietveld refinement, where the initial data for the crystal structure were taken from the model of Yangyang Dang et al.24. For band-gap and absorption coefficient calculation from the perovskite layer, data were recorded using a Shimadzu 3101UV–Vis. A superficial image of a PVK thin film was obtained with a Hitachi S-5500 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (see Fig. S1).

Theoretical details

Architecture device

An experimental perovskite solar cell with a specified configuration was analyzed using SCAPS, with the findings presented in Fig. 1. The thicknesses of the experimental layers23 were considered (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b and c provide the study’s results for estimating the implementation of devices with different layers (CdTe and CIGS). In addition, a device without an HTL was also examined, as depicted in Fig. 1d, to ascertain its performance.

Simulation parameters

It has been widely recognized that numerical modeling is quite important to improve the performance of solar cells. The ability to solve the fundamental equations of semiconductors and numerical modeling facilitates the understanding and prediction of the impacts of each layer. This study conducted simulations using SCAPS-1D software (version 3.3.10)24 under standard conditions. The software can resolve the Poisson equation, the electron and hole carrier continuity equations at steady state, and drift–diffusion equations. These equations are of utmost importance for accurately determining the J–V characteristics.

Based on the simulation of the solar cells, input parameters for each layer were introduced (see Table 1)23,25,26,27,28,29. These parameters were obtained from experimental and theoretical reports. The absorption coefficient for perovskite was obtained experimentally and compared to the results from Löper et al.29. Also, 4.0 eV and 5.1 eV work functions were used for the FTO and Au contacts23.

Density functional theory parameters

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were carried out to better understand the origin for the electronic band structure of MAPI perovskite. To perform such calculations, we modelled three perfect unit cells based on (a) cubic, (b) tetragonal and (c) orthorhombic structure, as shown in Fig. 2. SIESTA software version 4.1.5 was used to calculate the electronic band structure according to Density Functional Theory30. Based on the van der Waals Density Functional (vdW-DF), the electronic band structure was calculated using O. A. Vydrov y T. Van Voorhis functional (VV), which incorporates corrections for van der Waals interactions30,31. Also, it was employed a double zeta plus polarization basis set (DZP) to represent the molecular orbitals, then, the mesh cutoff was set to 150 Ry with an energy shift of 0.16. To get well converged results, the unit cell was relaxed until the maximum force interaction, which was lower than 0.01 eV/A30,31,32.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction

The crystalline structure of the perovskite film deposited on TiO2 was studied by XRD and is shown in Fig. 3. The results showed a peak at 38.5° (COD ID 7,206,075), which is associated with the reflections of the TiO2 anatase phase. According to the XRD results, the creation of the perovskite crystalline phase is confirmed, and the film shows a well-crystallized primary phase with a tetragonal structure, the diffraction peaks observed at two theta in 14.1, 19.90, 23.42, 24.45, 28.35, 31.78 and 40.43° correspond to the (110), (112), (211), (202), (220), (310) and (400) crystalline planes of the perovskite structure (tetragonal) (COD ID 7,218,931).

It was evaluated that XRD data inform the crystallographic tendency and tetragonal system (a = b ≠ c, α = γ = β = 90°) of the perovskite. We have calculated by MAUD software (version 2.9995) the value of lattice parameters for perovskite MAPI as a = b = 8.815, c = 12.467, a microstrain = 0.00203, and crystallite size with a value of 70 nm, while 73.9 nm using Sherrer’s33.

On the other hand, the texture coefficient (TC) was evaluated to infer the preferential growth orientation of perovskite film. The TC was calculated for the (110), (220), and (400) planes34. The estimates TC110, TC220, and TC400 are 1.12, 1.60, and 0.26, respectively. This suggests the preferred orientation is for the (220) plane. According to García A. et al. the changes in the surface energy of the perovskite grains are related to variations in the Gibbs free energy. Hence, when there is a growth of perovskite grains, these energies are affected35; therefore, according to the preferred orientation in the (220) plane, it is suggested that charge transport could be affected.

Optical results

The perovskite thin films underwent UV–Vis measurements to obtain optical results. Figure 4 shows the absorption coefficient, which measures how much light was absorbed by the material. The graph shows a good correspondence with previously reported results by other researchers, confirming the reliability of the absorbance obtained (see Fig. S2). To further validate the results, a comparison was made with a theoretical study29, which reported values of 105 cm−1. The comparison proved that the obtained values were within the expected range. In addition, energy gap measurements were carried out, and the data was presented in Fig. 5. The value of 1.55 eV indicates that the perovskite thin films successfully obtained CH3NH3PbI3, and the material is suitable for use in solar cells.

Electronic band structure of CH3NH3PbI3 calculated by DFT

Figure 6 shows the perovskite’s electronic band structure for (a) cubic, (b) tetragonal, and (c) orthorhombic crystal structure. As shown in Fig. 6, the electronic band structure varies depending on the crystal structure of the MAPI perovskite. For example, in the case of a cubic cell (a), the electronic band structure allows a band gap of around 1.50 eV, while in the case of the orthorhombic cell (b), that value increases to 3.90 eV. Finally, in the case of a tetragonal cell (c), the band gap calculated was 1.7 eV. We found that the tetragonal case presents a direct band gap while cubic and orthorhombic have an indirect band gap; it indicates that the tetragonal crystal structure has a band gap that facilitates the efficient transfer of electrons and holes for optoelectronic applications. Also, we found that the band gap obtained by DFT is higher than the experimental value reported in other research. However, the obtained result is consistent with another study as presented by Haiyan Jiang et al.36, who evaluated the changes produced in the bandgap energy by the variation of pressure and concluded that the increment of the pressure in the unit cell produces a decrement in the band gap energy. In this case, it is supposed that a more detailed study of the CH3NH3PbI3 could be necessary37.

Also, the density of states was calculated, as presented in Fig. 2. According to our results, the valence band are produced by the contribution of Pb and I atoms while in the case of the conduction band the main contributor results the I and H atoms.

Theoretical validation of experimental perovskite solar cell

Integrating experimental data into SCAPS for solar cell modelling is essential for validating models, accurately characterizing materials, estimating parameters, understanding non-ideal effects, optimizing designs, and ensuring the technology’s real-world viability. In this context, the J–V curves of devices were simulated, considering our experimental data (e.g., the absorption coefficient, and energy band gap). The results are presented in Fig. 7, which displays the J–V and EQE and is consistent with a previous report23.

Role of HTL in perovskite solar cell

The HTL plays a pivotal role in transferring holes from the PVK to the electrode by facilitating the extraction and transportation processes. This material must possess adequate energy levels, minimal visible and near-infrared absorption, excellent thermal and photochemical stability, and sufficient gap mobility to ensure optimal performance. These characteristics enable the effective transfer of holes, which is critical to the system’s overall functionality. Therefore, selecting the appropriate HTL is imperative in achieving optimal device performance.

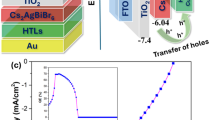

After analyzing, it becomes evident that the energy levels of solar cell configurations with and without HTL show a significant difference. These schemes (Fig. 8) illustrate that HTL limits the movement of electrons, which, in turn, encourages the creation of fresh electron–hole pairs. On the other hand, in the absence of HTL, electrons travel from the perovskite to the back contact, causing recombination due to leakage currents. Hence, HTL is an indispensable element of solar cells, as it enhances efficiency and reduces recombination.

In the simulation, the values obtained were 0.83 V for Voc, 18.7 mA/cm2 in Jsc, 60.7% for FF, and 9.42% in PCE. However, upon comparison with the cell simulated (Fig. 9a.) with HTL, a decrease of 0.1 V for Voc, 2.11 mA/cm2 for Jsc, 7.14% for FF, and 3.7% for PCE was observed. Furthermore, in Fig. 9b, a significant decrease in EQE can be observed. This decline could be attributed to the improper extraction and charge transportation from the perovskite to the electrode. These outstanding aspects are the significance of the HTL in the solar cell as it generates new electron–hole pairs, which increases the photogeneration and, thus, solar cell efficiency. In addition, it would facilitate the decrease of recombination by leakage currents upon subsequent contact.

Comparative study of Spiro-OMeTAD, CdTe & CIGS in perovskite solar cells

To validate the comparison, simulations performed on the perovskite solar cell using inorganic CdTe and CIGS absorber layers with the same thickness (213 nm) of the reference device (Spiro-OMeTAD simulation) are presented (Fig. 10).

Based on an extensive analysis, it has been found that the selection of materials has an important effect on the device’s performance. The energy diagrams are shown in Fig. 11. The results in Fig. 11a suggest that Spiro-OMeTAD has proven to be a more effective hole transporter, resulting in a higher Voc value. Furthermore, CIGS (Fig. 11b) demonstrates a stronger absorption of long-wavelength photons, leading to a more substantial collection of carriers than CdTe and Spiro-OMeTAD. In contrast, CdTe accumulates holes, leading to a larger change in Voc (Fig. 11c). While the EQE values for Spiro-OMeTAD and CdTe are relatively similar, on average, Spiro-OMeTAD displays higher EQE values, resulting in a higher Jsc. The EQE curves offer a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. As previously mentioned, the performance of Spiro-OMeTAD device is predominantly constrained by its absorber (perovskite), which possesses a band gap of 1.55 eV, corresponding to a wavelength of 800 nm. Conversely, the CIGS device, characterized by a narrower band gap of 1.1 eV, facilitates absorption in a different spectral region that extends up to 1100 nm 38. Consequently, CIGS has emerged as the material with the best performance in this study (see Table 2).

Figure 10b illustrates the cell’s quantum efficiency with copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) as the hole transporting layer (HTL). The initial impression might suggest that such a cell would perform inadequately due to the misalignment of energy levels. This misalignment impedes the electron from jumping from the CIGS layer to the perovskite layer, as depicted in Fig. 11b. Nevertheless, owing to the absorption capacity of the CIGS material, this cell exhibited a higher Jsc than expected. This effect is consistent with the findings of the external quantum efficiency test. Notably, CIGS contributes to effective carrier extraction, which is the principal function of the HTL. However, it does so to a lesser extent than Spiro-OMeTAD (Fig. 9a). Furthermore, CIGS has a cooperative effect with perovskite, which enhances the absorption of less energetic photons and improves carrier collection.

Optimized modelling of CIGS layer

Ultimately, we simulated the optimized perovskite solar cell. The optimization studies below were performed considering the values assigned in the parameter Table 1. Therefore, only variations will be made according to the study parameter to be optimized, keeping the other values constant. Subsequently, a final simulation of the optimized perovskite solar cell will be performed.

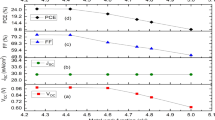

HTL thickness

To study the effect of HTL thickness, a thickness variation from 100 to 500 nm was performed to observe the performance behavior of the cell. The thicknesses were varied in increments of 100 nm, except for 213 nm, which is the experimental thickness obtained in perovskite cells with Spiro-OMeTAD as HTL. The simulation results are clearly presented in the Fig. 12 and Table 3, providing detailed analysis of the cell output parameters obtained.

The study reports a range of observations about the efficiency of solar cells. Specifically, the Voc was found to vary between 0.8 to 0.94 V, while the Jsc increased significantly from 21.36 to 29.05 mA/cm2. The FF also showed an improvement, increasing from 69.5 to 74.6%, while the efficiency increased from 12.02 to 20.37%. Further analysis revealed that the best efficiency was obtained at 500 nm, with an increase of 4.7% compared to the results obtained when simulating with 213 nm thickness. Interestingly, the device efficiency increased with thickness, indicating that the thicker the CIGS layer, the better the performance. This is a noteworthy finding, as it suggests that the performance is not limited to the thicknesses analyzed, which is promising for future applications. However, the study also observed that when using Spiro-OMeTAD as the HTL, the maximum efficiency was obtained at a thickness of 100 nm. This value is lower than what was observed with CIGS, indicating that the performance of the device using Spiro-OMeTAD as the HTL would be lower than that obtained with CIGS. Overall, these findings suggest that the thickness of the CIGS layer plays a relevant role in determining the efficiency device, and that using Spiro-OMeTAD as the HTL may not be as effective as using CIGS.

Defect density (NT)

The non-radiative recombination processes caused by a high defect density in the CIGS layer can adversely affect the charge carrier transport, leading to lower overall device performance, a higher film degradation rate, and lower stability. Thus, it becomes imperative to study the effect of the NT into the CIGS layer of the solar cell by varying the defect densities from 1012 to 101⁷ cm⁻3. The J-V curves obtained through simulations by shifting the defect density are shown in Fig. 13. Interestingly, the highest efficiency is observed at a defect density of 1013 cm⁻3. It is important to note that the efficiency is decreased by an increase or decrease in the defect density from 1013 cm⁻3, indicating that the choice of defect density is crucial in determining the overall efficiency of the perovskite device. To further understand the impact of the NT defect density, various output parameters have been analyzed, and the results are tabulated in Table 4.

The study suggests that the appearance of defects in the material greatly hinders the performance of the device. The simulations revealed that the lowest efficiency of 10.86% was obtained with a high defect density of 1017 cm−3, while a much higher efficiency of 17.11% was observed with a defect density in the order of 1013 cm−3. Beyond this threshold, the output parameters did not vary significantly. This finding suggests that reducing impurities in the material may not be necessary once the defect density is below a certain threshold. Therefore, it is essential to control the defect density during the manufacturing process to ensure the optimal performance of the solar cell.

Series resistance (Rs)

The presence of series resistance can have an adverse impact on the output characteristic parameters of a simulated cell, leading to a decrease in their values. This decline in fill factor is attributed to series resistance. To investigate this effect, the cell was simulated with varying resistance values ranging from 0 to 10 Ωcm2. The outcome of these simulations is presented in a Table 5, and the corresponding Fig. 14 depicts the behavior of the output parameters of the perovskite cell with CIGS as HTL when including series resistance. It is noteworthy that the efficiency achieved by the cell increases as the value of series resistance decreases.

The series resistance significantly impacts the output parameters of a perovskite cell with CIGS as HTL. The simulation Table 5 reveals that the cell’s fill factor gradually decreases with increased resistance, decreasing overall efficiency. The highest efficiency was achieved when resistance was at zero, with no change in Voc and a slight decrease in Jsc. However, reducing the series resistance value increases cell efficiency. For example, with a series resistance of 10 Ωcm2, the cell’s fill factor decreased from 72.8 to 56.21%. The findings demonstrate that the series resistance significantly impacts the device efficiency, reducing the fill factor, resulting in a decline in cell efficiency from 15.67 to 11.13%. This underscores the importance of minimizing the series resistance to ensure optimal cell performance. Interestingly, the Voc remained constant, indicating that the values utilized to evaluate the impact of series resistance were comparatively low. These results highlight the need to consider the effect of series resistance when designing and optimizing solar cells to achieve maximum efficiency.

Acceptor density (NA)

To calculate the acceptor density (NA), the density of acceptor states (which is equivalent to the density of hole doping) must first be multiplied by the probability that those states are occupied. This probability is determined by the value of the Fermi distribution at the energy of the acceptor state. Conversely, the density of donors is straightaway correlated to the electron mobility. To examine the effect of the charge carrier concentration, simulations were carried out within the range of 5.5 × 1013–5.5 × 1016 cm−3. The findings of this study are displayed in Fig. 15.

Based on the results, it can be observed in Table 6 that enhancing the acceptor density to 5.5 × 1016 cm−3 leads to a remarkable improvement in the cell’s output parameters. The Voc remains constant at 0.907 V, while the Jsc increases from 23.74 to 24.21 mA/cm2. Furthermore, the FF rises from 72.8 to 73.3%, boosting efficiency from 15.67% to 16.09%. This notable enhancement is attributed to the reinforced electric field of the junction, which promotes the separation of charges and enhances the device’s overall performance.

Temperature (K)

Like all photovoltaic devices, solar cells are responsive to temperature fluctuations. In this section, simulations were carried out, an in-depth examination of how temperature impacts solar cell performance. The research tested various temperature ranges, from 298 to 333 K, as illustrated in Fig. 16. The outcomes of our analysis are detailed in Table 7. It is clear that the characteristic parameters of the cell experienced a decrease. The Voc decreased from 0.918 V to 0.774 V, Jsc dropped from 24.14 to 22.72 mA/cm2, FF decreased from 73.6 to 66.25% and PCE went down from 16.31 to 11.65%. The highest efficiency of 16.31% was attained at 298 K.

The analysis reveals that alterations in temperature have a minimal effect on the Jsc of solar cells, despite a slight decline with an increase in temperature. This can be attributed to the diminution in bandgap of the semiconductor as light absorption increases with temperature. Conversely, the Voc and FF of the cell demonstrate a tendency to decrease with elevated temperature. The decrease in Voc and FF is approximately linear, and since the value of FF depends on Voc, the form factor also declines with temperature. The nearly linear decrease of Voc with temperature can be ascribed to the reduction in the width of the forbidden zone with an increase in temperature, resulting in a decrease in efficiency.

Work function (WF) in back contact

The quality and efficiency of a solar cell are heavily influenced by subsequent contacts. In the field of solid-state physics, the work function represents the minimum energy required to extract an electron from the highest level in the stationary Fermi distribution of a solid state and transfer it outside the surface of the solid. In order to determine the minimum energy necessary for optimal device performance, the work function values of the device back contact with CIGS as HTL were varied to a range between 4.8 to 5.4 eV, as illustrated in the accompanying Fig. 17.

The solar cells’ performance is shown in Table 8. At 4.8 eV, the cell efficiency was measured at 9.14%, and when the energy level was increased to 5.2 eV, the efficiency peaked at 17.78%. The Voc increased from 0.68 to 0.92 V, the Jsc increased from 22.31 to 25.3 mA/cm2, and FF rised from 60.31% to 76.4%. Interestingly, it was observed that beyond 5.2 eV, the output parameters of the cell did not change significantly. Therefore, it can be concluded that the highest efficiency is achieved at a work function of 5.2 eV.

Optimized solar cell

After obtaining the necessary parameters, a simulation was run for an improved device under the following conditions: CIGS thickness of 500 nm, NT of 1013 cm-3, Rs of 0 Ωcm2, NA of 5.5 × 1016 cm-3, temperature of 298 K, and anode work function of 5.2 eV. The obtained J–V curve for the perovskite-CIGS cell is shown in Fig. 18a), which was optimized by considering the previously analyzed and optimized aspects. The output parameters obtained from the simulation were Voc = 1.04 V, Jsc = 31.67 mA/cm2, FF = 86.0%, and PCE = 28.32%. Figure 18b) shows EQE for the perovskite-CIGS cell with the optimized parameters. An increase in efficiency percentage is observed due to the cooperative absorption process and generation of electron–hole pairs of the CIGS layer. The optimized CIGS parameters led to a significant enhancement in the efficiency of the perovskite solar cell. Therefore, it is concluded that the incorporation of CIGS into the perovskite solar cell improves its performance and could potentially stabilize it.

Final remarks

The research presented herein addresses a critical challenge in developing PVK devices, specifically the sensitivity of the PVK absorber layer to the presence of oxygen and water and the degradation of the usually used organic hole transport layer, Spiro-OMeTAD. DFT calculations were performed to understand the nature of the band gap for cubic, tetragonal, and orthorhombic crystal structures; it was found that the band gap could vary from 1.5 to 3.9 depending on the crystal structure obtained. It has been observed that the calculated band gap differs from the experimentally observed value. However, it is necessary to note that there could be a coexistence between the various phases or that experimentally, the orientations of the MAPI unit cells are randomly produced, which modifies the electronic interaction. As a result, the band gap is modified. The study assessed the effects of including inorganic absorber layers, such as CdTe and CIGS, in perovskite solar cells. It was discovered that adding a CIGS layer substantially improved the solar cell’s output parameters, particularly in Jsc and efficiency. Several factors were optimized to attain the best results, such as thickness, defect density, series resistance, acceptor density, temperature, and work function of the perovskite cell with CIGS as the hole transport layer (HTL). The efficiency showed a remarkable improvement, increasing from 15.67 to 28.32%, which is superior to the CIGS record solar cell16. The study’s findings suggest that incorporating a thin layer of CIGS into perovskite solar cells can significantly enhance their overall performance, thus providing a promising path for the optimal use of these devices. The study also emphasizes the importance of thoughtfully considering the materials used in constructing solar cells and optimizing their performance to achieve maximum efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from I. Montoya De Los Santos on reasonable request. DFT calculations in this study are performed with the SIESTA package (https://siesta-project.org/siesta/index.html). Lattice parameters for perovskite were obtained by using MAUD software (GitHub - luttero/maud: Materials Analysis Using Diffraction).

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(17), 6050–6051 (2009).

Yoo, J. J. et al. Efficient perovskite solar cells via improved carrier management. Nature 590(7847), 587–593 (2021).

Chowdhury, T. A. et al. Stability of perovskite solar cells: Issues and prospects. RSC Adv. 13, 1787–1810 (2023).

Saliba, M. et al. Cesium-containing triple cation perovskite solar cells: Improved stability, reproducibility and high efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1989–1997 (2016).

Magomedov, A. et al. Pyridination of hole transporting material in perovskite solar cells questions the long-term stability. J. Mater. Chem. C 6, 8874–8878 (2018).

Chen, J. & Park, N.-G. Inorganic hole transporting materials for stable and high efficiency perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 122(25), 14039–14063 (2018).

Adhikari, K. R., Gurung, S., Bhattarai, B. K. & Soucase, B. M. Comparative study on MAPbI3 based solar cells using different electron transporting materials. Physica Status Solidi (c) 13(1), 13–17 (2016).

Azri, F., Meftah, A., Sengouga, N. & Meftah, A. Electron and hole transport layers optimization by numerical simulation of a perovskite solar cell. Solar Energy 181, 372–378 (2019).

Karimi, E. & Ghorashi, S. M. B. Investigation of the influence of different hole-transporting materials on the performance of perovskite solar cells. Optik 130, 650–658 (2017).

Kumar, A. & Singh, S. Advancement in inorganic hole transport materials for inverted perovskite solar cells. J. Electr. Mater. 49(10), 5840–5881 (2020).

Elseman, A. M., Sajid, S., Shalan, A. E., Mohamed, S. A. & Rashad, M. M. Recent progress concerning inorganic hole transport layers for efficient perovskite solar cells. Appl. Phys. A 125(7), 1–12 (2019).

Wu, Q. et al. Kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 as a low-cost inorganic hole-transporting material for high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 7(51), 28466–28473 (2015).

Abnavi, H., Maram, D. K. & Abnavi, A. Performance analysis of several electron/hole transport layers in thin film MAPbI3-based perovskite solar cells: a simulation study. Opt. Mater. 118, 111258 (2021).

Nair, S. & Gohel, J. V. A review on contemporary hole transport materials for perovskite solar cells. Nanotech. Energy Environ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33774-2_63 (2020).

First Solar Press release. First solar achieves yet another cell conversion efficiency world record, 24 February 2016

Nakamura, M., Yamaguchi, K., Yimoto, Y., Yasaki, Y., Kato, T., Sugimoto, H. Cd-free Cu(In, Ga)(Se, S)2 thin-film solar cell with new world record efficacy of 23.35%. 46th IEEE PVSC, (see also http://www.solar-frontier.com/eng/news/2019/0117_press.html); 9(6):1863–1867 (2019).

Xiao, J. W. et al. Ligand engineering on CdTe quantum dots in perovskite solar cells for suppressed hysteresis. Nano Energy 46, 45–53 (2018).

Jošt, M. et al. 21.6%-Efficient monolithic perovskite/Cu(In, Ga)Se2 tandem solar cells with thin conformal hole transport layers for integration on rough bottom cell surfaces. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 583–590 (2019).

Rahman, M. et al. A novel CdTe ink-assisted direct synthesis of CdTe thin films for the solution-processed CdTe solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 7715–7730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04578-7 (2020).

Khosroshahi, R. et al. Engineering of CIGS nanoparticle inks for colloidal stability, uniform film formation and application as HTL for perovskite solar cells. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 106, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2021.10.034 (2022).

Zahra, F., Hasan, M. M., Hossen, M. B. & Islam, M. R. Deep insights into the optoelectronic properties of AgCdF3-based perovskite solar cell using the combination of DFT and SCAPS-1D simulation. Heliyon 10(13), e33096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33096 (2024).

Harun-Or-Rashid, M. et al. Exploring new lead-free halide perovskites RbSnM3 (M = I, Br, Cl) and achieving power conversion efficiency > 32 %. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 197, 112437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2024.112437] (2025).

De Los, M. et al. Optimization of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells: A theoretical and experimental study. Solar Energy 199, 198–205 (2020).

Burgelman, M., Nollet, P. & Degrave, S. Modeling polycrystalline semiconductor solar cells. Thin Solid Films 361–362, 527–532 (2000).

Dang, Y. et al. Bulk crystal growth of hybrid perovskite material CH3NH3PbI3. CrystEngComm 17, 665–670 (2015).

Cetin, C. et al. Inorganic p-type semiconductors as hole conductor building blocks for robust perovskite solar cells. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2(89), 1800032 (2018).

Valencia, D. et al. Optimization of Cu (In, Ga) Se2 (CIGSe) thin film solar cells parameters through numerical simulation and experimental study. Solar Energy 224, 298–308 (2021).

Nykyruy, L. I., Yavorskyi, R. S., Zapukhlyak, Z. R., Wisz, G. & Potera, P. Evaluation of CdS/CdTe thin film solar cells: SCAPS thickness simulation and analysis of optical properties. Opt. Mater. 92, 319–329 (2019).

Löper, P. et al. Complex refractive index spectra of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite thin films determined by spectroscopic ellipsometry and spectrophotometry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6(1), 66–71 (2014).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Phys.: Conden. Matt. 14(11), 2745 (2002).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio O(N) materials simulation. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, 2745–2779 (2002).

García, A. et al. Siesta: Recent developments and applications. J. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.01.026 (2020).

Balaji Gandhi, M. et al. Investigation on guanidinium bromide incorporation in methylammonium lead iodide for enhanced efficiency and stability of perovskite solar cells. Solar Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.01.026 (2023).

Asl, H. Z. & Rozati, S. M. Influence of texture coefficient on the electrical properties of spray-deposited fluorine-doped tin oxide thin film. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 32, 1668–1676 (2021).

Fang, Z., Yan, N. & (Frank) Liu, S. Modulating preferred crystal orientation for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells—From progress to perspectives. InfoMat https://doi.org/10.1002/inf2.12369 (2022).

Jiang, H., Xue, H., Wang, L., Tang, F. & Si, F. Effect of pressure-induced structural phase transition on electronic and optical properties of perovskite CH3NH3PbI3. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 96, 59–65 (2019).

Flores-Livas, J. A. et al. Emergence of hidden phases of methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) upon compression. Phys. Rev. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevmaterials.2.08 (2018).

Ferdous Rahman, Md. et al. Improving the efficiency of a CIGS solar cell to above 31% with Sb2S3 as a new BSF: a numerical simulation approach by SCAPS-1D. RSC Adv. 14, 1924–1938. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA07893K (2024).

Acknowledgements

L.M.P. acknowledges the financial support from ANID through Convocatoria Nacional Subvención e Instalación en la Academia Convocatoria Año 2021, Grant No. SA77210040. LMP and DL acknowledge partial financial support from ANID through FONDECYT 1240985

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Project administration; M.C.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft; V.I.M.O.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; E.D.R.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review and editing; E.B.D.C.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-review and editing; M.O.M.: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Writing–original draft; L.M.P.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Project administration; D.L.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya De Los Santos, I., Courel, M., Moreno-Oliva, V.I. et al. The study of inorganic absorber layers in perovskite solar cells: the influence of CdTe and CIGS incorporation. Sci Rep 15, 10353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88338-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88338-0